Abstract

In summer 2015, the Iowa Supreme Court unanimously struck down a restriction that would have prevented physicians from administering a medication abortion remotely through video teleconferencing. In its ruling, the Iowa Supreme Court stated that the restriction would have placed an undue burden on a woman's right to access abortion services. It is crucially important for clinicians – especially primary care clinicians, obstetrician–gynecologists, and all health care providers of telemedicine services –to understand the implications of this recent ruling, especially in rural settings. The Court’s decision has potential ramifications across the country, both for women’s access to abortion, and for the field of telemedicine. Today telemedicine abortion is only available in Iowa and Minnesota, and 18 states have adopted bans on it. If telemedicine abortions are indeed being unconstitutionally restricted as the Iowa Supreme Court determined, court decisions reversing these bans could improve access to abortion services for the 21 million reproductive-age women living in these 18 states, which have a limited supply of obstetrician–gynecologists, mostly concentrated in urban, metropolitan areas. Beyond the potential effects on abortion access, we argue that the Court’s decision also has broader implications for telemedicine, by limiting state boards of medicine’s role regarding the restriction of politically controversial medical services when provided through telemedicine. The interplay between telemedicine policy, abortion politics, and the science of medicine is at the heart of the Court’s decision, and has meaning beyond Iowa’s boarders, for reproductive-age women across the United States.

In summer 2015, the Iowa Supreme Court unanimously struck down a restriction that would have prevented physicians from administering a medication abortion (also known as “medical abortion”) remotely through video teleconferencing. In its ruling, the Iowa Supreme Court stated that the restriction would have placed an undue burden on a woman's right to access abortion services.1 The case was brought by Planned Parenthood of the Heartland (PPHeartland), challenging the Iowa Board of Medicine’s 2013 decision requiring a physician’s physical presence when a patient receives medication to induce an abortion. Prior to the Iowa Board of Medicine’s decision, patients in Iowa accessed many medical services, including medication abortion, through telemedicine. The Iowa Board of Medicine cited patient safety concerns as the impetus for its policy change, but rigorous research shows that neither the number of abortions, nor associated adverse outcomes increased in Iowa since the telemedicine option was first introduced in 2008.2,3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (the College), which supports telemedicine access to medication abortion,4 raised concerns that the Iowa Board of Medicine’s rule would pose a particular burden for rural residents seeking the procedure. In 2008, only 6.4% of obstetrician–gynecologists practiced in rural areas nationwide, and currently, more than half of rural women don’t have access to reproductive health services anywhere in their county.5 It is crucially important for clinicians – especially primary care clinicians, obstetrician–gynecologists, and all health care providers of telemedicine services –to understand the implications of this recent ruling, especially in rural settings. The Court’s decision has potential ramifications across the country, both for women’s access to abortion, and for the field of telemedicine.

Telemedicine Abortion: Practice and Evidence

Clinician shortages in many medical specialties and limited resources have catalyzed a dramatic increase in the use of telemedicine, which now plays a pivotal role in the delivery of healthcare, especially in rural areas. Telemedicine encompasses a vast array of services, from basic electronic communications between patients and clinicians, to more complex, innovative technology in medical procedures, like physician-guided robotic surgical procedures.

Striving for improvements in women’s access to early abortion care, PPHeartland was an early adopter of advancements in telemedicine. In 2008, their clinic network in Iowa launched a program using telemedicine to provide medication abortion in clinics without a physician on-site. Across the state of Iowa, over 60% of the network’s clinics offer medication abortion through telemedicine.6

An abortion by telemedicine closely resembles the in-person process for the procedure.7 The patient is greeted first by a nurse or trained technician, who reviews her medical history, administers an ultrasound, measures basic vital signs, and provides information about the procedure and follow-up process. The patient then meets with the doctor, using a videoconferencing system that allows the doctor and patient to communicate with each other directly. The doctor reviews the patient’s records and ultrasound results, answers questions, and initiates the procedure. The doctor’s click of a mouse or computer password remotely opens a drawer in front of the patient. The drawer contains the pills (mifepristone and misoprostol5) that induce an abortion; the patient swallows one immediately, in the virtual presence of the doctor, and takes the other pill later at home. This process of taking mifepristone at the office and misoprostol later at home is the same as what is done with in-person medication abortion. The patient follows up with a clinic visit two weeks later, and in the unlikely event of an incomplete abortion (medication abortion has a 92–95% success rate6,8), the clinic schedules the patient for a surgical abortion at a physician-staffed clinic.

Since the widespread implementation of telemedicine provision of medication abortion in Iowa, there has been no significant differences between women who received services through telemedicine compared with face-to-face provision of medication abortion in the prevalence of adverse events, incomplete abortion, or blood transfusion;2 also, patient satisfaction with telemedicine abortion is high.2 A 2011 survey of 600 women using PPHeartland for abortion services found comparable clinical outcomes for telemedicine patients and women who obtained face-to-face care.2 Both forms of care had similar success rates, with few adverse events. An overwhelming majority of patients (99%) reported it was easy to hear and see the physician, and nearly the same number (94%) reported being “very satisfied” with the procedure. Most patients (89%) said they felt comfortable asking questions while interacting with the physician through a computer.

The Implications of Court’s Ruling

Medication abortion care – and other healthcare services – delivered through telemedicine are particularly relevant to rural residents, whose reproductive health care may be delayed and needs may go unmet due to geographic distances and lack of health care provider access. Before the telemedicine abortion program was implemented in Iowa, 91 percent of counties in the states lacked a known abortion health care provider.2

The Iowa Supreme Court noted that telemedicine is being used to provide many types of health care services. But the Iowa Board of Medicine’s restriction singled out medication abortion when it imposed a requirement that doctors be physically present to perform patient services. “It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the board’s medical concerns about telemedicine are selectively limited to abortion,” the court determined.1

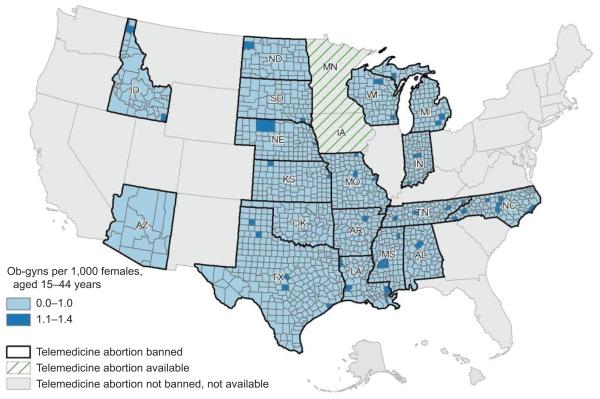

Today telemedicine abortion is only available in Iowa and Minnesota, and 18 states have adopted bans on it.9 Other states neither expressly allow nor ban telemedicine abortion. Nearly 21 million reproductive-age women live in these 18 states where the procedure is banned; these states also have substantial rural populations and few obstetrician–gynecologists per capita, especially in rural counties (Figure 1). There are 200 telemedicine networks in the U.S., with 3,500 service sites and in 2011, more than 300,000 remote consultations were delivered by the Veterans Health Administration.10 Research indicates that telemedicine ensures access to safe abortion services for rural women,2 but abortion politics are complex and current laws reflect that abortion services are treated differently than other types of clinical care provided through telemedicine. Increased use of telemedicine for abortion and other reproductive health services could help reduce the significant disparities in access that exist for rural communities, compared with urban and suburban areas.

Figure 1.

State telemedicine abortion availability and obstetrician–gynecologists (ob-gyns) per 1,000 females, aged 15–44 years. Ob-gyn data from the Area Health Resources Files (AHRF). 2014–2015. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce, Rockville, MD. Population data from 2010 Census Summary File 1: United States. Prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2011. Figure created by David Van Riper and Jason Borah, Spatial Analysis Core, Minnesota Population Center.

Iowa is the first State Supreme Court to find a telemedicine abortion ban unconstitutional. Since the decision relied in part on federal constitutional law, it can – and likely will – lead to challenges to telemedicine abortion bans in other states. If telemedicine abortions are indeed being unconstitutionally restricted, court decisions reversing these bans could improve access to abortion services for women in these 18 states. One of these states is Texas, where – in June 2015 - the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the state’s requirement that abortion clinics meet ambulatory surgical center standards did not impose an undue burden on a “large fraction” of Texas women seeking abortions.11 Only a handful of Texas abortion clinics, all in major metropolitan areas, meet those standards. For women in rural Texas, telemedicine may present a safe, accessible alternative to accessing medication abortion services if that state’s current ban on telemedicine abortion were lifted. Moreover, Texas women were reportedly already seeking abortion pills on the black market and crossing into Mexico for unsafe abortions due to a lack of health care providers;12 therefore, access to safe medication abortion is even more critical in places with limited access to clinic-based abortion services.

The ruling sets a precedent for how much authority state medical boards can exercise over the regulation of telemedicine. If the court had ruled for the Iowa Board of Medicine , it could have opened the door for other state boards of medicine to limit the use of telemedicine, for abortion or other politically controversial medical services (e.g. emergency contraception), potentially avoiding the need for lengthy state legislative processes to make policy change. The Iowa case is significant because if the court had ruled that an appropriate patient-physician relationship could not be established or a proper diagnosis could not be made without the doctor's physical presence, it could have served as a spring board for increased state action in creating carve-outs and exceptions to telemedicine services, limiting the potential for populations with health care access issues to reap the full benefits of telemedicine that delivers safe medical services. Not unlike the recent Hobby Lobby13 decision, this is a case that strikes deep into the political heart of the nation, but politics can obscure the core issues: access to safe medical care through telemedicine, and what constitutes an appropriate patient-physician relationship and treatment options. The Iowa decision emphasized that available science, not political rhetoric, should drive America’s telemedicine policies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Van Riper and Jason Borah in the Spatial Analysis Core at the Minnesota Population Center for assistance in preparation of the map, presented as Figure 1. The authors also thank Sara Abiola, JD, PhD for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number R24HD041023. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Planned Parenthood of the Heartland Inc. et al v. Iowa Board of Medicine. 865 N.W.2d 252 (Iowa 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grossman D, Grindlay K, Buchacker T, Lane K, Blanchard K. Effectiveness and acceptability of medical abortion provided through telemedicine. Obstet Gyneco. 2011 Aug;118(2 Pt 1):296–303. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318224d110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman D, Grindlay K, Buchacker T, Potter JE, Schmertmann CP. Changes in service delivery patterns after introducing telemedicine provision of medical abortion in Iowa. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):73–78. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women ACOG Committee Opinion No. 613: Increasing access to abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(5):1060–5. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000456326.88857.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Health Disparities in Rural Women ( http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Health-Disparities-in-Rural-Women)

- 6.Boonstra H. Medication Abortion Restrictions Burden Women and Providers—and Threaten U.S. Trend Toward Very Early Abortion. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2013;16(1):18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice bulletin no. 143: medical management of first-trimester abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):676–92. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000444454.67279.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ngo TD, Park MH, Shakur H, Free C. Comparative effectiveness, safety and acceptability of medical abortion at home and in a clinic: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(5):360–70. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.084046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guttmacher Institute, Mediation Abortion September 1, 2015, ( http://www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_MA.pdf)

- 10.American Telemedicine Association Telemedicine Frequently Asked Question. ( http://www.americantelemed.org/about-telemedicine/faqs#)

- 11.Whole Woman's Health v. Cole. No. 14-50928 (5th Cir. June 9, 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassett L. The return of the back-alley abortion. ( http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/04/03/back-alley-abortions_n_5065301.html) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burwell v,. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. 2014. 573 U.S. 22.