Abstract

Background/Aims

To determine factors predictive of discordance in staging liver fibrosis using liver biopsy (LB) and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) elastography in patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB).

Methods

Consecutive patients with CHB who underwent LB and ARFI elastography on the same day from November 2010 to March 2013 were prospectively recruited from three tertiary hospitals.

Results

We analyzed 105 patients (median age of 47 years). The F0–1, F2, F3, and F4 fibrosis stages were identified in 27 (25.7%), 27 (25.7%), 21 (20.0%), and 30 (28.6%) patients, respectively. The areas under the receiver operating characteristics curves for ARFI elastography in assessing ≥F2, ≥F3, and F4 was 0.814, 0.848, and 0.752, respectively. The discordance of at least one stage between LB and ARFI was observed in 68 patients (64.8%) and of at least two stages in 16 patients (15.2%). In a multivariate analysis, advanced fibrosis stage (F3–4) was the only factor that was negatively correlated with one-stage discordance (p=0.042). Moreover, advanced fibrosis stage was negatively (p=0.016) correlated and body mass index (BMI) was positively (p=0.006) correlated with two-stage discordance.

Conclusions

Advanced fibrosis stage (F3–4) was a predictor of nondiscordance between LB and ARFI elastography; BMI also influenced the accuracy of ARFI elastography.

Keywords: Acoustic radiation force impulse, Discordance, Liver cirrhosis, Hepatitis B, chronic

INTRODUCTION

Since the prognosis and treatment strategy for patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) are closely related to the degree of fibrosis, assessment of liver fibrosis is important in patients with CLD.1 Until now, liver biopsy (LB) has been considered the gold standard for assessing liver fibrosis;2 however, its use is limited because of its invasiveness, risk of complications, sampling error,3,4 and interpretational variability.5 In addition, these factors make sequential LBs impractical, especially when repeated examinations are required to monitor response to antiviral or anti-fibrotic treatment. All of these issues have encouraged research into noninvasive approaches. As a results, several noninvasive surrogates for LB have been introduced for the assessment of liver fibrosis: transient elastography (TE) (Fibroscan®; EchoSens, Paris, France),6–8 acoustic radiation force impulse elastography (ARFI elastography, Acuson S20000; Siemens Medical Solutions, Mountain View, CA, USA),9 and several serum fibrosis prediction indices.10

After vigorous validation, liver stiffness (LS) measurement using TE has become a widely applied procedure for assessing the severity of liver fibrosis.6 Furthermore, LS measurement using TE can be used to select treatment strategies, predict prognosis, and monitor disease progression. However, unsatisfactory TE performance has been reported for patients with ascites, a narrow intercostal space, or obesity.11,12 In addition, necroinflammatory activity, as indicated by a high alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, is the single most important confounder and has been known to diminish the accuracy of LS measurement using TE.13,14

Recently, ARFI elastography, which uses radiation-forced impulses to measure LS while using B-mode ultrasonography, was also introduced.15 In contrast to TE which has a fixed region of interest (ROI) at a fixed insertion depth, ARFI elastography has a flexible ROI at variable depths which enables LS measurement in patients with ascites and obesity.16–18 Furthermore, ARFI elastography has another advantage in that it enables LS measurement during a routine ultrasonographic evaluation of the abdomen. The ease of this study facilitates sequential LS measurements during routine outpatient visits for follow-up.19 However, most investigations on ARFI elastography have been performed in European patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC), whereas few studies are available that used Asian populations, where chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection is endemic.15 Furthermore, it has not been determined yet which factors influence the accuracy of ARFI elastography in Asian patients with CHB. Necessarily, noninvasive surrogates for LB, including ARFI elastography, are always subject to discordance compared to the histologic staging of fibrosis. Thus, a study of factors associated with discordance between noninvasive surrogates and LB could enable us to more effectively use noninvasive methods.

Hence, we investigated the diagnostic performance of ARFI elastography in assessing different degrees of liver fibrosis in patients with CHB from three Korean tertiary hospitals. We further identified factors that influence the accuracy of ARFI elastography by investigating which factor is related to discordant LB and ARFI elastography results in staging liver fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

From November 2010 to March 2013, consecutive patients with CHB who underwent both LB and LS measurement using ARFI elastography on the same day at three tertiary hospitals of Shinchon Severance Hospital, Seoul, Kyungpook National University Hospital, Daegu, and Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea were prospectively recruited for this study. CHB was defined as the persistent presence of serum hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) for more than 6 months. LB was performed to assess the severity of fibrosis prior to antiviral treatment.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: a history of hepatocellular carcinoma or other malignancy at the time of LB, a LB specimen shorter that 10 mm, co-infection with HIV or hepatitis C or hepatitis D virus, alcohol ingestion in excess of 40 g/day for more than 5 years, LB and ARFI elastography performed on different days, Child-Pugh classification B or C, evidence of decompensated liver cirrhosis, including a history of variceal bleeding, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or a previous history of antiviral therapy (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant or responsible family member after detailed explanation of the study and possible complications of the diagnostic procedures had been fully explained. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each hospital.

2. Clinical data

Demographic details and body mass index (BMI) were collected. The following laboratory data were also collected from all patients at the time of LB and ARFI elastography: serum total cholesterol, serum albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ALT, prothrombin time, and platelet count. HBsAg and hepatitis B e antigen were measured using standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA at Shinchon Severance Hospital, Roche Modular E170, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany at Kyungpook National University Hospital, and Bio Focus Co., Ltd., Uiwang, Korea at Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital). Hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels were measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay (Amplicor HBV Monitor Test; Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland; detection limit approximately 12 IU/mL at Shinchon Severance Hospital and Kyungpook National University Hospital and Abbott m2000, Abbott Molecular Inc., Des Plaines, IL, USA; detection limit 10 IU/mL at Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital).

3. LS measurement using ARFI elastography

For all patients, ARFI elastography was performed on the same day as LB by a single physician at each hospital (all physicians had more than 2 years of experience with ultrasonography and more than 300 examinations with ARFI elastography). The physicians were blinded with regard to the clinical and biochemical data of each patient. Details of the technical background and examination procedure have been described previously.20,21 Briefly, while performing a real time B-mode imaging, a 10×5-mm ROI was placed over vessel-free liver parenchyma. Tissue in the ROI was excited by short-duration acoustic pulses to generate localized tissue displacement, which resulted in shear-wave propagation away from the region of excitation. Shear-wave propagation was tracked using ultrasonography correlation-based methods. The shear-wave velocity can be reproduced by measuring the time to peak displacement at each location, and the shear-wave velocity of the tissue is proportional to the square root of tissue elasticity. All measurements were performed on the right hepatic lobe, using an intercostal view with breath-holding technique. In each patient, LS was measured 1 to 3 cm below the liver capsule based on the previous study.17 To ensure quality of measurement, more than 10 successful acquisitions in each patient were performed and mean value was considered to represent the elastic modulus of the liver.15 Results were expressed as meters per second (m/sec). The interquartile range (IQR) was defined as an index of the LS values’ intrinsic variability and corresponded to the 25th and 75th percentile intervals around the LS result containing 50% of the valid measurements.

4. LB examination

Percutaneous LB was performed using a 16- to 18-gauge disposable needle immediately after ARFI elastography. Before performing LB, we examined target liver parenchyma for biopsy and obtained ARFI values. Then, LB was performed. The LB specimens were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections 4 μm thick were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Masson’s trichrome. All tissue samples were evaluated by an experienced hepatopathologist at each institute who was blinded to the patients’ clinical data including LS results. Liver histology was evaluated semiquantitatively according to the Batts and Ludwig scoring system.22 Fibrosis was staged on a 0–4 scale: F0, no fibrosis; F1, portal fibrosis; F2, periportal fibrosis; F3, septal fibrosis; and F4, cirrhosis. Significant fibrosis was defined as stage F2 or greater, advanced fibrosis as F3 or greater, and cirrhosis as F4.

5. Definitions of discordance between LB and ARFI elastography

To define discordance between LB and ARFI elastography, the external ARFI cutoff values for staging liver fibrosis were adopted from a previous Korean study.15 Cutoff values were 1.13 m/sec for significant fibrosis (≥F2), 1.50 m/sec for advanced fibrosis (≥F3) which was calculated from the same cohort,15 and 1.98 m/sec for cirrhosis (F4). Based on these external cutoff values and previous studies,23,24 discordance was defined as a discordance between fibrosis stages determined by ARFI elastography and LB of one or two stages.

6. Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics are reported as medians (ranges) or n (%), as appropriate. The independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables. The chi-square test or Fischer exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves and areas under the ROC curves (AUROCs) were used to estimate diagnostic performance. Optimal internal cutoff values were calculated that maximized sensitivity (Se) and specificity (Sp). Positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) and positive and negative likelihood ratios were also computed. Univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent factors related to discordance between LB and LS measurement by ARFI elastography. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The only variables which were significant in univariate analysis (p<0.05) could be used for multivariate analysis. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

1. Baseline characteristics

After excluding 19 patients according to predefined exclusion criteria, a total of 105 patients were included in the final analysis. The baseline characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 1. The median age was 47 years (range, 19 to 82 years) and male gender predominated (n=73, 69.5%). The median BMI was 23.4 kg/m2 and the median AST and ALT levels were 39 IU/ L and 46 IU/L, respectively. The mean and median ARFI velocities were 1.89 m/sec and 1.59 m/sec, respectively. The median IQR was 0.35 m/sec, the IQR/median 0.24, and the IQR/mean 0.24.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (n=105)

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Demographic data | |

| Age, yr | 47 (19–82) |

| Male gender | 73 (69.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.4 (16.1–35.7) |

| Laboratory data | |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 165 (109–265) |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 4.3 (3.0–5.4) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.7 (0.2–2.0) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, IU/L | 39 (9–945) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, IU/L | 46 (4–489) |

| Prothrombin time, INR | 1.00 (0.88–1.17) |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 182 (104–333) |

| HBV DNA, IU/L | 651.25 (0.02–170,000) |

| HBeAg positivity | 59 (56.2) |

| ARFI velocity | |

| Mean, m/sec | 1.89±0.84 |

| Median, m/sec | 1.59±0.52 |

| Interquartile range, m/sec | 0.35 (0.09–2.40) |

| Interquartile range/median | 0.24 (0.06–1.47) |

| Interquartile range/mean | 0.24 (0.06–1.34) |

Data are presented as median (range), number (%), or mean±SD.

INR, international normalized ratio; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; ARFI, acoustic radiation force impulse.

2. Liver histology and corresponding ARFI velocity

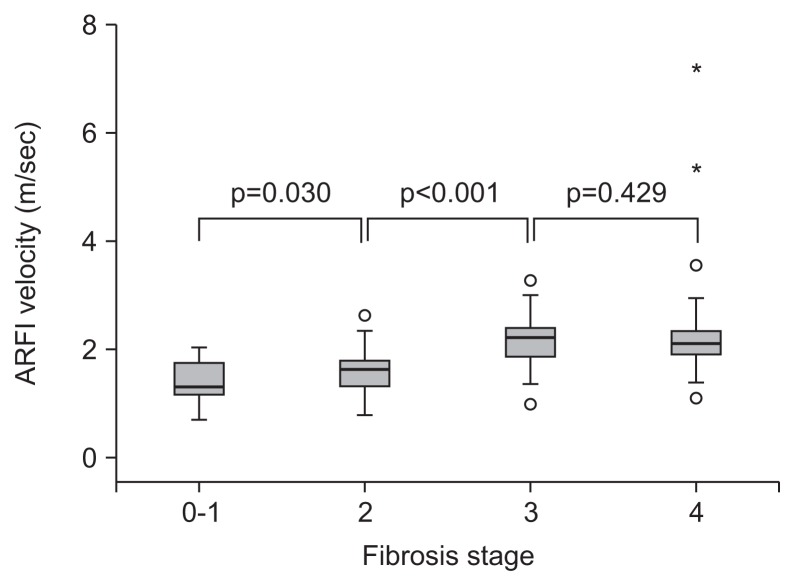

The histologic fibrosis stages and corresponding ARFI velocities are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The proportions of patients with fibrosis stages F0–1, F2, F3, and F4 were 25.7% (n=27), 25.7% (n=27), 20.0% (n=21), and 28.6% (n=30), respectively. The mean ARFI velocity of each fibrosis stage were 1.38 m/sec for F0–1, 1.61 m/sec for F2, 2.17 m/sec for F3, and 2.40 m/sec for F4. The mean ARFI velocity tended to increase as fibrosis stage increased (p<0.05 for F0–1 vs F2 and F2 vs F3), but there was no significant difference between stage F3 and stage F4 (p=0.429) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Box plots of acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) velocity in each fibrosis stage. There were statistically significant differences in ARFI velocity between stage F0–1 versus F2 and stage F2 versus F3 (p=0.030 and p<0.001, respectively), whereas no significant difference was identified between stage F3 versus F4 (p=0.429).

3. Prevalence of discordance between LB and ARFI velocity

Using discriminant external cutoff values which were suggested in a previous study,15 a discordance of at least one stage (gray colored) between LB and ARFI velocity was observed in 68 patients (64.8%) and at least two stages (dark gray colored) were observed in 16 patients (15.2%) (Table 2). As a whole, fibrosis stage was underestimated in 16 patients (15.2%) and overestimated in 52 patients (49.5%) by ARFI elastography in comparison to LB (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of the Fibrosis Stages according to the Histology and External Cutoff of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Velocity

| Fibrosis stage estimated by histology | Fibrosis stage estimated by ARFI velocity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| F0–1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |

|

| ||||

| ARFI<1.13 m/sec | 1.13 m/sec≤ARFI<1.50 m/sec | 1.50 m/sec≤ARFI<1.98 m/sec | ARFI≥1.98 m/sec | |

| F0–1 (n=27) | 6 | 13 | 7 | 1 |

| F2 (n=27) | 3 | 7 | 12 | 5 |

| F3 (n=21) | 1 | 2 | 4 | 14 |

| F4 (n=30) | 0 | 2 | 8 | 20 |

| Total (n=105) | 10 | 24 | 31 | 40 |

Gray color, subjects with one-stage discordance in the fibrosis stage as assessed using histology and ARFI velocity; Dark gray color, subjects with two-stage discordance in the fibrosis stage as assessed using histology and ARFI velocity.

ARFI, acoustic radiation force impulse.

4. Diagnostic performance of ARFI elastography and optimal cutoff values

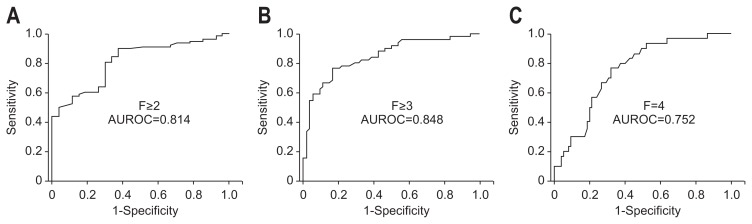

With regard to the diagnostic performance of ARFI elastography in predicting histologic liver fibrosis, the AUROC was 0.814 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.729 to 0.900) for significant fibrosis (≥F2) (Fig. 2A), 0.848 (95% CI, 0.773 to 0.923) for advanced fibrosis (≥F3) (Fig. 2B), and 0.752 (95% CI, 0.656 to 0.849) for cirrhosis (F4) (Fig. 2C), respectively. The optimal internal cutoff values to predict fibrosis stage using ARFI elastography were 1.31 m/sec for ≥F2 (Se, 89.7%; Sp, 63.0%; PPV, 94.9%; NPV, 22.2%), 1.81 m/sec for ≥F3 (Se, 78.4%; Sp, 78.8%; PPV, 90.2%; NPV, 53.7%), and 1.98 m/sec for F4 (Se, 66.7%; Sp, 73.3%; PPV, 66.7%; NPV, 73.3%), respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for acoustic radiation force impulse values in diagnosing significant fibrosis (≥F2) (A), advanced fibrosis (≥F3) (B), and cirrhosis (F4) (C). The areas under the ROC curves were 0.814 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.729 to 0.900) for significant fibrosis (≥F2), 0.848 (95% CI, 0.773 to 0.923) for advanced fibrosis (≥F3), and 0.752 (95% CI, 0.656 to 0.849) for cirrhosis (F4). AUROC, areas under the ROC curve.

5. Factors affecting the discordance between histology and ARFI velocity

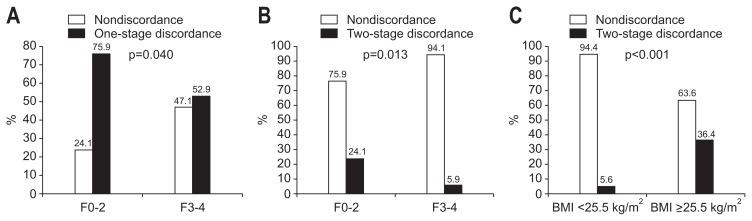

On univariate analysis, advanced fibrosis stage (F3–4) was the only significant factor negatively associated with one-stage discordance between LB and ARFI velocity (p=0.042; odds ratio, 0.426; 95% CI, 0.187 to 0.969) (Table 3). The one-stage discordance rate was significantly lower in patients with stages F3–4 than in those with stages F0–2 (52.9% vs 75.9%, respectively; odds ratio, 0.426; 95% CI, 0.187 to 0.969; p=0.040) (Fig. 3A).

Table 3.

Factors Affecting Discordance in Fibrosis Staging between Histology and Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Velocity

| Variable | One-stage discordance (n=68, 64.8%) | Two-stage discordance (n=16, 15.2%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Univariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|

|

|

||||

| p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | p-value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Clinical data | |||||

| Age, yr | 0.613 | - | 0.422 | - | - |

| Male gender | 0.229 | - | 0.276 | - | - |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.998 | - | 0.002 | 0.006 | 1.291 (1.075–1.551) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 0.505 | - | 0.916 | - | - |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 0.335 | - | 0.247 | - | - |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.324 | - | 0.378 | - | - |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, IU/L | 0.084 | - | 0.181 | - | - |

| Alanine aminotransferase, IU/L | 0.129 | - | 0.923 | - | - |

| Prothrombin time, INR | 0.995 | - | 0.739 | - | - |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 0.479 | - | 0.358 | - | - |

| HBV DNA, IU/L | 0.246 | - | 0.716 | - | - |

| HBeAg positivity | 0.185 | - | 0.438 | - | - |

| Histological data | |||||

| F3–4 (vs F0–2) | 0.042 | 0.426 (0.187–0.969) | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.181 (0.045–0.730) |

| ARFI elastography | |||||

| Interquartile range, m/sec | 0.751 | - | 0.132 | - | - |

| Interquartile range/median | 0.423 | - | 0.145 | - | - |

| Interquartile range/mean | 0.903 | - | 0.644 | - | - |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; INR, international normalized ratio; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; ARFI, acoustic radiation force impulse.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of nondiscordance and discordance in stages F0–2 and stages F3–4. One-stage discordance was more frequently observed in patients with stages F0–2 than those with stages F3–4 (odds ratio, 0.426; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.187 to 0.969; p=0.040) (A); similarly, two-stage discordance was more frequently identified in patients with stages F0–2 than those with stages F3–4 (odds ratio, 0.197; 95% CI, 0.053 to 0.740; p=0.013) (B). Using the optimal cutoff body mass index (BMI) value, two-stage discordance was more frequently identified in patients with BMI ≥25.5 kg/m2 than those with BMI <25.5 kg/m2 (odds ratio, 9.714; 95% CI, 2.381 to 33.329; p<0.001) (C).

Univariate analysis showed that BMI and advanced fibrosis stage (F3–4) were significant factors affecting two-stage discordance (all p<0.05) and subsequent multivariate analysis showed that both BMI and advanced fibrosis stage (F3–4) were statistically significant positive and negative predictors of two-stage discordance, respectively (p=0.006, odds ratio, 1.291, 95% CI, 1.075 to 1.551; and p=0.016, odds ratio, 0.181, 95% CI, 0.045 to 0.730, respectively) (Table 3). The two-stage discordance rate was significantly lower in patients with stages F3–4 than F0–2 (5.9% vs 24.1%, respectively; odds ratio, 0.197; 95% CI, 0.053 to 0.740; p=0.013) (Fig. 3B).

Considering that BMI is positively associated with two-stage discordance, further analysis was done by stratifying the study population into two groups according to an optimal cutoff BMI value which maximize the sum of Se and Sp (25.5 kg/m2 with Se of 75.0% and Sp of 76.4%). Two-stage discordance was identified in only four of 72 patients (5.6%) with BMI <25.5 kg/m2, whereas it was noted in 12 of 33 patients (36.4%) with BMI ≥25.5 kg/m2 (odds ratio, 9.714; 95% CI, 2.381 to 33.329; p<0.001) (Fig. 3C).

DISCUSSION

LS measurement using ARFI elastography was recently introduced and is considered a noninvasive and reproducible tool to assess the degree of liver fibrosis.17,25,26 To date, most studies that investigated the ability of ARFI elastography to estimate the degree of liver fibrosis have been performed in European patients with CHC.25,27 In contrast, studies have rarely been conducted in patients with CHB, especially in Asian countries, where the prevalence of CHB is high.28 In order for the use of ARFI elastography to become more widespread, its performance should be validated in Asian patients with CHB who have a different range of BMIs and viral kinetics from Europeans with CHC. Here, we aimed to examine the performance of ARFI elastography in Korean patients with CHB through a multicenter study. We found that ARFI elastography exhibited acceptable diagnostic accuracy in predicting liver fibrosis. In our study, the AUROCs were 0.814 for predicting ≥F2, 0.848 for ≥F3, and 0.752 for F4, respectively. This performance is quite similar to that of a previous Asian study (AUROC, 0.74 for ≥F2 and 0.79 for F4, respectively).15 Although further studies of Asian subjects with CHB are required, our results might indicate that ARFI elastography could be applied in Asian populations as well as Western populations.

To date, histologic fibrosis has been the reference standard for cross-sectional studies that sought to assure the performance of noninvasive tools. However, these comparative methods have several problems because certain inherent problems in LB affect its accuracy3,4 and cannot reflect the dynamic process of liver fibrosis.29 Nevertheless, identification of factors associated with discordance between noninvasive surrogates and LB is an important prerequisite for clarifying potential confounders that can influence the diagnostic accuracy of a given noninvasive surrogate. Factors associated with discordance are also important for enhancing its performance in assessing intrahepatic fibrotic burden by controlling the identified influencing factors. In this study, we defined “significant discordance,” based on previous studies,23,24,30 as a discordance of at least two stages of fibrosis between ARFI elastography and LB, although the definition of discordance can potentially bias the results depending on the proportion of each fibrosis stage.21 However, we additionally analyzed our data using the extended definition of “discordance,” or at least one stage of discordance in fibrosis staging between ARFI elastography and LB, to minimize the potential bias. We found that fibrosis stage F0–2 and BMI are independent factors influencing the accuracy of ARFI elastography.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the prevalence of discordance between LB and ARFI elastography and its predictors in Asian patients with CHB using a cohort from three tertiary medical institutes. In this study, advanced fibrosis stage (F3–4) at LB is a predictor of nondiscordance between LB and ARFI elastography, regardless of whether discordance is defined as a one or two-stage difference, This is similar to the results of a previous study regarding the discordance of TE and LB.23 Indeed, most discordance in our study was caused by overestimation of liver fibrosis by ARFI elastography in patients with F0–2 (21 cases of 27 histologic F0–1 and 17 of 27 histologic F2). Although it was hypothesized in a previous study regarding the discordance between TE and LB that this high prevalence of discordance in those with an early fibrotic burden (F0–2) might be due to high ALT levels at this stage of fibrosis,15 ALT levels were not a predictor of significant discordance in our study and were statistically similar between patients with F0–2 and F3–4. This might be due to the relatively small sample size in our study or the relatively low accuracy of ARFI elastography in diagnosing early fibrotic burden.31 Although advanced fibrosis stage (F3–4) at LB is a predictor of nondiscordance between LB and ARFI elastography, its clinical application might be limited because we cannot obtain histologic data ahead of LB.

In our study, BMI was also selected as a predictor that positively affects the risk of discordance between ARFI elastography and LB, again similar to the result of a previous study regarding TE in patients with CHB.32 Using internal cutoff values to calculate discordance, BMI was also selected as the only predictor of significant discordance (p=0.018; odds ratio, 1.224; 95% CI, 1.036 to 1.447). To date, several other studies have also reported that a high BMI is significantly related to the risk of measurement failure or low diagnostic accuracy of ARFI elastography, as well as TE.12,33 All these support the hypothesis that BMI can influence the diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive tools in certain ways. Although increased thickness of the thoracic belt or an increase in the steatotic burden itself related to higher BMIs are potential candidates, the exact mechanism for how BMI influences the diagnostic accuracy of ARFI elastography is not well understood. There is a paradoxical pitfall that obese patients with potential liver fibrosis are most in need of noninvasive tools, but are not able to fully benefit from their accurate use due to the influence of a high BMI on the accuracy of noninvasive tools, such as ARFI elastography. To overcome this problem, an XL probe can be used in cases of TE.34 However, there are few studies on this issue in ARFI elastography, so further study is needed.

The internal cutoff values (1.31 m/sec for ≥F2, 1.81 m/sec for ≥F3, and 1.98 m/sec for F4) were slightly higher that external cutoff values in a previous Asian study15 that proposed 1.13 m/ sec for ≥F2 and 1.81 m/sec for F4, respectively. This disagreement between the internal and external cutoff values might be due to differences in the etiology of the liver disease that could have influenced the cutoff values (CHB only vs mixed); the heterogeneity of the causes of liver diseases is known as one of the important factors influencing the diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive models.35 Although we proposed new cutoff values for patients with CHB, larger population based studies are needed to validate our results for application in clinical practice.

Several issues still remain unresolved. First, we could not investigate the clinical role of ARFI elastography as a non-invasive monitoring tool to predict dynamic changes in liver fibrosis because, due to our cross-sectional design, follow-up ARFI elastography was not available in most patients. Second, although we identified predictors of patients with discordance, it is unclear whether the long-term prognosis of patients with discordance differs from that of patients with nondiscordance. This should be clearly elucidated in order to use the identified influencing factors in clinical practice. Third, in addition to the higher prevalence of discordance (64.8% of one-stage discordance), the uneven distribution of fibrosis stage (74.3% of the study population had significant fibrosis [≥F2]) may be another limitation of our study due to the potential for spectrum bias. Finally, the overestimating influence of high ALT level which was proposed in several previous studies13,19 was not identified in our study. Although the exact reason for this phenomenon is not clear, the small sample size of our study might be related to this potential false negative result. Further large-scale study should be followed to resolve this issue.

In conclusion, advanced fibrosis stage (F3–4) showed a positive correlation with nondiscordance between LB and ARFI elastography. BMI may be another candidate that influences the accuracy of ARFI elastography. Future studies should focus on methods of enhancing the diagnostic accuracy of ARFI elastography using our identified factors in clinical practice.

Supplementary materials

Flow diagram of the selected study population. A total of 124 consecutive patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) who underwent liver biopsy and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) elastography were enrolled. Nineteen patients were excluded based on our exclusion criteria. Finally, a total of 105 patients were selected for statistical analysis. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Supplementary Table 1.

Liver Histology and Corresponding Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Velocity

| Stage | No. (%) | ARFI velocity, m/sec* |

|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 27 (25.7) | 1.38±0.37 |

| 2 | 27 (25.7) | 1.61±0.42 |

| 3 | 21 (20.0) | 2.17±0.59 |

| 4 | 30 (28.6) | 2.40±1.18 |

ARFI, acoustic radiation force impulse.

ARFI velocity is described as the mean±SD.

Supplementary Table 2.

Diagnostic Performances of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Velocity

| Fibrosis stage | AUROC (95% CI) | Cutoff values | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | NPV, % | PPV, % | −LR | +LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥F2 | 0.814 (0.729 –0.900) | 1.31 | 89.7 | 63.0 | 22.2 | 94.9 | 0.16 | 2.42 |

| ≥F3 | 0.848 (0.773 –0.923) | 1.81 | 78.4 | 78.8 | 53.7 | 90.2 | 0.27 | 3.7 |

| F4 | 0.752 (0.656 –0.849) | 1.98 | 66.7 | 73.3 | 73.3 | 66.7 | 0.45 | 2.5 |

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; LR, likelihood ratio.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI10C2020). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: 2008 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1315–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:495–500. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedossa P, Dargere D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–1457. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.09022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poynard T, Halfon P, Castera L, et al. Variability of the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves in the diagnostic evaluation of liver fibrosis markers: impact of biopsy length and fragmentation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:733–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rousselet MC, Michalak S, Dupre F, et al. Sources of variability in histological scoring of chronic viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 2005;41:257–264. doi: 10.1002/hep.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, et al. Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SU, Han KH, Ahn SH. Transient elastography in chronic hepatitis B: an Asian perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5173–5180. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i41.5173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foucher J, Chanteloup E, Vergniol J, et al. Diagnosis of cirrhosis by transient elastography (FibroScan): a prospective study. Gut. 2006;55:403–408. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.069153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedrich-Rust M, Wunder K, Kriener S, et al. Liver fibrosis in viral hepatitis: noninvasive assessment with acoustic radiation force impulse imaging versus transient elastography. Radiology. 2009;252:595–604. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2523081928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lackner C, Struber G, Liegl B, et al. Comparison and validation of simple noninvasive tests for prediction of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:1376–1382. doi: 10.1002/hep.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talwalkar JA, Kurtz DM, Schoenleber SJ, West CP, Montori VM. Ultrasound-based transient elastography for the detection of hepatic fibrosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1214–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirli R, Sporea I, Bota S, Jurchis A. Factors influencing reliability of liver stiffness measurements using transient elastography (M-probe)-monocentric experience. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:e313–e316. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arena U, Vizzutti F, Corti G, et al. Acute viral hepatitis increases liver stiffness values measured by transient elastography. Hepatology. 2008;47:380–384. doi: 10.1002/hep.22007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castera L, Foucher J, Bernard PH, et al. Pitfalls of liver stiffness measurement: a 5-year prospective study of 13,369 examinations. Hepatology. 2010;51:828–835. doi: 10.1002/hep.23425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon KT, Lim SM, Park JY, et al. Liver stiffness measurement using acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) elastography and effect of necroinflammation. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1682–1691. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rifai K, Cornberg J, Mederacke I, et al. Clinical feasibility of liver elastography by acoustic radiation force impulse imaging (ARFI) Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:491–497. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sporea I, Sirli RL, Deleanu A, et al. Acoustic radiation force impulse elastography as compared to transient elastography and liver biopsy in patients with chronic hepatopathies. Ultraschall Med. 2011;32(Suppl 1):S46–S52. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1245360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi H, Ono N, Eguchi Y, et al. Evaluation of acoustic radiation force impulse elastography for fibrosis staging of chronic liver disease: a pilot study. Liver Int. 2010;30:538–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SU, Han KH, Park JY, et al. Liver stiffness measurement using FibroScan is influenced by serum total bilirubin in acute hepatitis. Liver Int. 2009;29:810–815. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park H, Park JY, Kim do Y, et al. Characterization of focal liver masses using acoustic radiation force impulse elastography. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:219–226. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Son CY, Kim SU, Han WK, et al. Normal liver elasticity values using acoustic radiation force impulse imaging: a prospective study in healthy living liver and kidney donors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:130–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis: an update on terminology and reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1409–1417. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199512000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SU, Kim JK, Park YN, Han KH. Discordance between liver biopsy and Fibroscan® in assessing liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B: risk factors and influence of necroinflammation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SU, Seo YS, Cheong JY, et al. Factors that affect the diagnostic accuracy of liver fibrosis measurement by Fibroscan in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:498–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sporea I, Sirli R, Popescu A, Danila M. Acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI): a new modality for the evaluation of liver fibrosis. Med Ultrason. 2010;12:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sporea I, Bota S, Peck-Radosavljevic M, et al. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse elastography for fibrosis evaluation in patients with chronic hepatitis C: an international multicenter study. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:4112–4118. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fierbinteanu-Braticevici C, Andronescu D, Usvat R, Cretoiu D, Baicus C, Marinoschi G. Acoustic radiation force imaging sonoelastography for noninvasive staging of liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5525–5532. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim SU, Han KH, Ahn SH. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis: time to move from cross-sectional studies to longitudinal ones. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1472–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucidarme D, Foucher J, Le Bail B, et al. Factors of accuracy of transient elastography (fibroscan) for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2009;49:1083–1089. doi: 10.1002/hep.22748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim BK, Fung J, Yuen MF, Kim SU. Clinical application of liver stiffness measurement using transient elastography in chronic liver disease from longitudinal perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1890–1900. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding H, Wu T, Ma K, et al. Noninvasive measurement of liver fibrosis by transient elastography and influencing factors in patients with chronic hepatitis B-A single center retrospective study of 466 patients. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2012;32:69–74. doi: 10.1007/s11596-012-0012-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaffer OS, Lung PF, Bosanac D, et al. Acoustic radiation force impulse quantification: repeatability of measurements in selected liver segments and influence of age, body mass index and liver capsule-to-box distance. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e858–e863. doi: 10.1259/bjr/74797353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myers RP, Pomier-Layrargues G, Kirsch R, et al. Feasibility and diagnostic performance of the FibroScan XL probe for liver stiffness measurement in overweight and obese patients. Hepatology. 2012;55:199–208. doi: 10.1002/hep.24624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frulio N, Trillaud H. Ultrasound elastography in liver. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:515–534. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Flow diagram of the selected study population. A total of 124 consecutive patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) who underwent liver biopsy and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) elastography were enrolled. Nineteen patients were excluded based on our exclusion criteria. Finally, a total of 105 patients were selected for statistical analysis. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Supplementary Table 1.

Liver Histology and Corresponding Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Velocity

| Stage | No. (%) | ARFI velocity, m/sec* |

|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 27 (25.7) | 1.38±0.37 |

| 2 | 27 (25.7) | 1.61±0.42 |

| 3 | 21 (20.0) | 2.17±0.59 |

| 4 | 30 (28.6) | 2.40±1.18 |

ARFI, acoustic radiation force impulse.

ARFI velocity is described as the mean±SD.

Supplementary Table 2.

Diagnostic Performances of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Velocity

| Fibrosis stage | AUROC (95% CI) | Cutoff values | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | NPV, % | PPV, % | −LR | +LR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥F2 | 0.814 (0.729 –0.900) | 1.31 | 89.7 | 63.0 | 22.2 | 94.9 | 0.16 | 2.42 |

| ≥F3 | 0.848 (0.773 –0.923) | 1.81 | 78.4 | 78.8 | 53.7 | 90.2 | 0.27 | 3.7 |

| F4 | 0.752 (0.656 –0.849) | 1.98 | 66.7 | 73.3 | 73.3 | 66.7 | 0.45 | 2.5 |

AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; LR, likelihood ratio.