Abstract

Monandry, in which a female has only one mating partner during the reproductive period, is established when a female spontaneously refrains from re-mating, or when a partner male interferes with the attempts of a female to mate again. In the latter case, however, females often have countermeasures against males, which may explain why polyandry is ubiquitous. Here, I demonstrate that the genital appendage, or scape, of the female orb-web spider (Cyclosa argenteoalba) is injured after her first mating, possibly by her first male partner. This female genital mutilation (FGM) permanently precludes copulation, and females appear to have no countermeasures. FGM is considered to confer a strong advantage to males in sexual conflicts over the number of female matings, and it may widely occur in spiders.

Keywords: genitalia, sexual conflict, epigynum, mating frequency

1. Introduction

The mating system of animals, especially female mating frequency, has fitness consequences for both sexes [1]. Monandry, in which a female has one mating partner, is established when a female spontaneously refrains from mating with multiple males, and/or when a male prevents a partner female from mating with other males [2]. Males use various methods of interference, including mate guarding, prolonged copulation, injecting chemical substances to decrease the likelihood of a female re-mating, and mating plugs (which block the copulatory openings in the female) [3]. On the other hand, females often resist these methods, and these methods do not always perfectly secure the paternity of the males [4–7]. A recent study revealed that polyandry is ubiquitous in animals [8], which suggests that the countermeasures of females are usually effective.

Genital coupling is necessary for successful mating in many animals, and it would be impeded by genitalia damage. In fact, in some male spiders, genitalia or parts of genitalia such as sclerites or embolus are broken after mating to form mating plugs and cannot be used again [9]. On the other hand, studies about the effect of female genital damage after mating on the subsequent copulation ability of females are scarce.

In some female Araneidae spiders, a small projection, or scape, covers the copulatory openings of the genitalia (epigynum); this appendage can be mutilated in many females [10,11]. Such mutilation may interfere with genital coupling [12], and could be used to control female mating frequency. This study examines this hypothesis using the orb-web spider, Cyclosa argenteoalba, in a series of staged matings.

2. Methods

I used 84 virgin adult Cyclosa argenteoalba females from bamboo forests in Osaka and Kyoto, Japan in 2014. Some of them were collected as penultimate subadult females, and were kept until they made their final moult. Other adults were collected on their moulting webs, which were characterized by their small size, reduced number of radii, lack of spiral threads and presence of fibrous decorations [13], indicating that the spiders had just moulted to adults. They were convincingly assumed to be virgins, because preliminary observations had revealed that no female mates with a male when on a moulting web. The spiders were released in a fenced garden observation area (9 × 2 m), located in Shimamoto, Osaka, where the females built their webs. Individual spiders were distinguished by their photographs (C. argenteoalba exhibit individual variation in silver and black marking patterns [14]) and web locations. Adult males were also collected and kept in vials. The observation area was separated from the natural habitat of the spiders by residential buildings, and whereas experimental spiders could emigrate from it, no immigration occurred during the study. This set-up isolated subject females from outside (non-experimental) males.

(a). General procedure

The genitalia of each female was inspected under a dissection microscope before she was allowed to mate. She was then returned to her web. After she regained her sitting posture, a male was introduced. Her response, the occurrence of copulation and sexual cannibalism, and the number and duration (the time between genital contact and separation) of palpal insertions, were recorded using normal-speed (Pentax Optio WG-2, 30 frames per second (FPS)) and high-speed cameras (Casio EXILIM EX-F1, 300 FPS). Normally, a copulation bout in this species consists of two separate palpal insertions (see Results). Copulation was judged unsuccessful when, despite male courtship, no palpal insertion was observed for 1 h, or the male left the web without palpal insertion. I inspected females after mating to verify whether the scape remained or not. Each male was returned to a vial.

(b). Experiment 1: copulation ability after genital mutilation

Each of 54 virgin females was paired with a male for staged mating. For five pairs, copulation was interrupted after the first palpal insertion because of sexual cannibalism or strong wind, and among the remaining 49 females, 13 disappeared from the observation area soon after the first mating, perhaps because of emigration. The remaining 36 mated females (five with a scape and 31 without a scape) were coupled with another male to determine if they could copulate.

(c). Experiment 2: artificial genital mutilation

Ten virgin females were anaesthetized with CO2, and their scapes were cut using fine scissors to mimic natural genital mutilation (figure 1d). Damage from the procedure appeared negligible, as no haemolymph was observed at the site, and the spiders subsequently resumed normal web building and prey capture. The mutilation apparently did not cause pain, because the scape has no sensory hair [12] and anaesthesia appeared effective. Ten control virgin females were also anaesthetized with CO2 but were not mutilated. Females from the experimental and control groups were both coupled with a male, and their ability to copulate was observed.

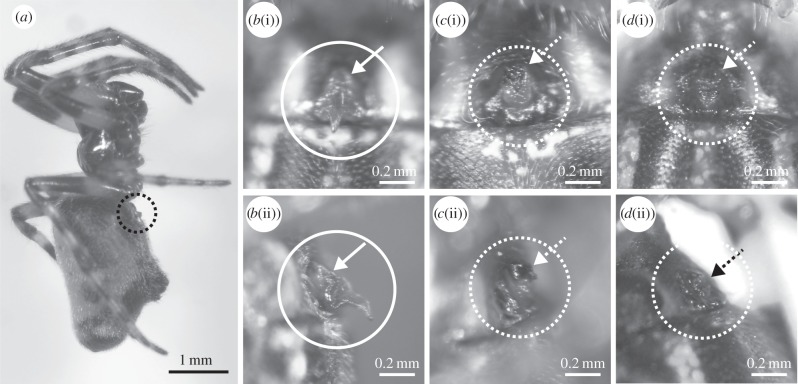

Figure 1.

(a) Lateral view of mated and mutilated female of Cyclosa argenteoalba. (b–d) Close-up photo of frontal ventral abdomen of (b) virgin female, (c) mated and mutilated female and (d) virgin and artificially mutilated female (picture brightness was enhanced). (i) Ventral and (ii) lateral view. Epigynum with or without scape is shown within a solid white or dotted circle, respectively. Spade-shaped projections seen in b(i) and b(ii) are scapes. Solid and dotted white or black arrows indicate the basal part of the scape where the appendage is cut during mutilation. See also Tanikawa [11].

(d). Experiment 3: the timing of mutilation in a copulation bout

Ten virgin females were subjected to staged mating. After the first palpal insertion, I removed the female from the web and looked for her scape. During this time, the male continued courting for the second insertion in eight pairs. I returned the female to her web and observed whether the second insertion occurred.

3. Results

Every virgin female had a scape on the basal plate of the epigynum (figure 1b). Scapes were wrinkled spade-shaped projections, and were bent in the middle. Copulation occurred on a mating thread spun by the male and the males courted females by vibrating this thread. After several courting trials, all females exhibited an accepting posture by exposing their genitalia to the males. The males then attempted to insert one of their two pedipalps. When the insertion was successful, the pair separated and the male courted the female again for the second insertion.

In experiment 1, among the 49 females that completed copulation, five retained their scapes, and all other females were mutilated, i.e. their scapes were cut at their basal part (figure 1a,c). The mutilation rate was approximately 90% (44/49). Two mutilated females received only one palpal insertion; the partner males continued courting after the first insertion and attempted the second insertion repeatedly, but all trials failed. The remaining 47 females received two insertions. Median duration of insertion and its interquartile range were 0.89 and 0.73–1.27 s, respectively, for the first insertion, and 0.85 and 0.62–1.07 s, respectively, for the second insertion.

At the re-mating trial, all males courted females, irrespective of being mutilated or not, and all females exhibited accepting posture to males. However, all mutilated females failed copulation, despite the repeated attempts of the males to insert their pedipalps (electronic supplementary material, video S1). Copulation was successful in four of five unmutilated females, which had scapes (electronic supplementary material, video S2). The difference in mating success was significant (Fisher's exact test, p < 0.0001). Average courting durations were 8.01 min for mutilated (n = 30) and 5.00 min for unmutilated females (n = 5).

In experiment 2, all artificially mutilated females failed copulation. For the control virgin females, copulation was successful in nine cases, and failed in only one case. The success ratio was significantly different (Fisher's exact test, p < 0.001).

In experiment 3, all females retained their scapes after the first palpal insertion. Recoupling resulted in successful second insertion in seven pairs, and all females lost their scapes after this coupling. In the other three pairs, the second insertion did not occur, because males stopped courting in two cases and a female did not respond to courting in one case. Females in these three cases retained their scapes.

4. Discussion

A series of staged matings of C. argenteoalba revealed that one mating bout consisted of two palpal insertions, and was in most cases accompanied by female genital mutilation (FGM), by removal of the scape. Once mutilated, either naturally or artificially, no female successfully mated. Mutilated females did not appear to stop re-mating spontaneously to avoid harassment from males, because males pursued and courted both mutilated and unmutilated females similarly. The response of all mated females to these subsequent courtships instead suggests that whereas females pursue re-mating, males engage in FGM to enforce lifetime monandry in C. argenteoalba. The scape is presumably an essential appendage that the male genitalia must clasp before palpal insertion [15], and mutilation potentially destroys this fine mechanism of genital coupling. In most cases, FGM occurred after the second palpal insertion, which is logical, because if mutilation occurred after the first insertion, then even the partner male could not complete the second insertion, as observed twice in experiment 1. These findings imply that the mutilation is an intended act and that the scape is not accidentally damaged.

Recently, FGM was also found to secure paternity in Larinia jeskovi, another species of orb-weaving spider [16]. FGM in L. jeskovi is very similar to that in C. argenteoalba. In L. jeskovi, the tegular apophysis of a pedipalp cut the side of the basal part of the scape halfway [16]. The same mechanism may also exist in C. argenteoalba, and it explains why two palpal insertions are necessary for successful mutilation: at each insertion, males possibly cut each of the right and left halves of the scape, although mutilation apparently does not always occur after two insertions in L. jeskovi.

Mutilated females were frequently (90% of all females at a maximum) found in the field (K.N. 2011–2014, personal observation), indicating that FGM is not an artefact of the experiment. Why did mutilated females respond to courting even though they could not re-mate? The females may not have recognized that they were mutilated. To date, there is no evidence that the scape has a sensory system [12]. Although spider females are considered at increased risk of predation and have decreased foraging opportunity during the mating trial [17], these costs may be negligible to C. argenteoalba, and therefore females do not stop responding to males. Alternatively, the females may attempt to capture and eat the second male (sexual cannibalism), but this is unlikely. Overall, the rate of sexual cannibalism was very low; among 120 mating trials in this study, cannibalism occurred only four times. These four cases of cannibalism, in addition to five other cannibalism events (K.N. 2014, unpublished observation), occurred after palpal insertions, suggesting that pre-copulation cannibalism does not occur, or occurs rarely, in this species. As mutilated females do not complete copulation, they do not have the opportunity to capture and cannibalize males, making it unlikely that cannibalism is their motivation for courting males. Another question raised in this study is why females accepted all courting males, even though they mate with only one male throughout their lives. The sex ratio, mate-encounter rate and variation in male quality are areas for future investigation to explain this lack of choosiness in females.

If FGM is a mechanism for males to restrict the re-mating of females, then it is more efficient than other previously known mechanisms, including mate guarding, manipulation by chemical substances or placing mating plugs. Indeed, no mutilated female re-mated, and copulation ability, once lost, was not restored. Whereas the mutilation rate was high (approx. 90%), the cost for males to restrict the re-mating of females in this manner is considered low. In contrast to other species, C. argenteoalba males do not have to spend a long time deterring rival males, or sacrifice their mating ability by plugging female genitalia with broken pieces of their pedipalps [9]. Females appear to have no efficient way to counteract FGM. Sexual cannibalism might protect females if it occurred before mutilation, but it would not be a significant countermeasure, as the cannibalism rate was very low. Why do females accept mutilation? One answer may be that FGM is a recently developed trait, and the females may not have had time to evolve countermeasures. This explanation seems unlikely, because FGM is observed in other spiders of genus Cyclosa [11], which suggests that mutilation may be an ancestral trait. Alternatively, females may seldom have the opportunity to mate with a second male. Information about sex ratio and mate-encounter rate in the field will be required to validate this hypothesis.

FGM in C. argenteoalba (this study) and L. jeskovi [16] is a previously unknown mechanism to realize monandry in animals. In bean weevils [18] and dung flies [19], female genitalia are damaged during copulation, but this injury does not inhibit re-mating [20]. In some ponerine ants, mutilation deprives the females of their mating ability, but the mutilated organ is a pair of vestigial wings, not genitalia [21]. Female genital damage has been found to occur in many Araneoidea species [16], and more FGM-driven monandry is expected to be found in these species. Comparison of species with and without FGM is anticipated to advance our understanding of the evolution of social systems and sexual conflict.

Acknowledgements

I thank Midori Nakata, Dr Keizo Takasuka and Dr Atushi Ushimaru for their help during the study. I also thank Dr Matthias Foellmer and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Ethics

The experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines for ethological studies from the Japan Ethological Society.

Data accessibility

All essential data are available in the text.

Competing interests

I declare I have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was partly supported by a JSPS grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (C) (no. 26440251).

References

- 1.Slatyer RA, Mautz BS, Backwell PRY, Jennions MD. 2012. Estimating genetic benefits of polyandry from experimental studies: a meta-analysis. Biol. Rev. 87, 1–33. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00182.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnqvist G, Andrés JA. 2006. The effects of experimentally induced polyandry on female reproduction in a monandrous mating system. Ethology 112, 748–756. ( 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01211.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnqvist G, Rowe L. 2013. Sexual conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avila FW, Sirot LK, LaFlamme BA, Rubinstein CD, Wolfner MF. 2011. Insect seminal fluid proteins: identification and function. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56, 21–40. ( 10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144823) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnsen A, Lifjeld JT, Rohde PA, Primmer CR, Ellegren H. 1998. Sexual conflict over fertilizations: female bluethroats escape male paternity guards. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 43, 401–408. ( 10.1007/s002650050507) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koprowski JL. 1992. Removal of copulatory plugs by female tree squirrels. J. Mammal 73, 572–576. ( 10.2307/1382026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foellmer MW. 2008. Broken genitals function as mating plugs and affect sex ratios in the orb-web spider Argiope aurantia. Evol. Ecol. Res. 10, 449–462. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor ML, Price TAR, Wedell N. 2014. Polyandry in nature: a global analysis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 29, 376–383. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2014.04.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uhl G, Nessler S, Schneider J. 2010. Securing paternity in spiders? A review on occurrence and effects of mating plugs and male genital mutilation. Genetica 138, 75–104. ( 10.1007/s10709-009-9388-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levi H. 1995. The neotropical orb-weaver genus Metazygia (Araneae: Araneidae). Bull. Mus. Comp. Zool. 154, 63–151. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanikawa A. 1992. A revisional study of the Japanese spiders of the genus Cyclosa MENGE (Araneae: Araneidae). Acta Arachnol. 41, 11–85. ( 10.2476/asjaa.41.11) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eberhard W, Huber B. 2010. Spider genitalia: precise maneuvers with a numb structure in a complex lock. In The evolution of primary sexual characters in animals, pp. 249–284. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takasuka K, Yasui T, Ishigami T, Nakata K, Matsumoto R, Ikeda K, Maeto K. 2015. Host manipulation by an ichneumonid spider ectoparasitoid that takes advantage of preprogrammed web-building behaviour for its cocoon protection. J. Exp. Biol. 218, 2326–2332. ( 10.1242/jeb.122739) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakata K, Shigemiya Y. 2015. Body-colour variation in an orb-web spider and its effect on predation success. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 116, 954–963. ( 10.1111/bij.12640) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhl G, Nessler SH, Schneider J. 2007. Copulatory mechanism in a sexually cannibalistic spider with genital mutilation (Araneae: Araneidae: Argiope bruennichi). Zoology 110, 398–408. ( 10.1016/j.zool.2007.07.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mouginot P, Prügel J, Thom U, Steinhoff Philip OM, Kupryjanowicz J, Uhl G. 2015. Securing paternity by mutilating female genitalia in spiders. Curr. Biol. 25, 2980–2984. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2015.09.074) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herberstein M, Schneider J, Elgar M. 2002. Costs of courtship and mating in a sexually cannibalistic orb-web spider: female mating strategies and their consequences for males. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 51, 440–446. ( 10.1007/s00265-002-0460-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crudgington HS, Siva-Jothy MT. 2000. Genital damage, kicking and early death. Nature 407, 855–856. ( 10.1038/35038154) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward P, Hemmi J, Roosli T. 1992. Sexual conflict in the dung fly Sepsis cynipsea. Funct. Ecol. 6, 649–653. ( 10.2307/2389959) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosken DJ, Martin OY, Born J, Huber F. 2003. Sexual conflict in Sepsis cynipsea: female reluctance, fertility and mate choice. J. Evol. Biol. 16, 485–490. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00537.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukumoto Y, Abe T, Taki A. 1989. A novel form of colony organization in the ‘queenless’ ant Diacamma rugosum. Physiol. Ecol. Jpn 26, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All essential data are available in the text.