Abstract

Background

In Canada, discussion about changing from cytology to human papillomavirus (hpv) dna testing for primary screening in cervical cancer is ongoing. However, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care has not yet made a recommendation, concluding that the evidence is insufficient.

Methods

We used the cervical cancer and hpv transmission models of the Cancer Risk Management Model to study the health and economic outcomes of primary cytology compared with hpv dna testing in 14 screening scenarios with varying screening modalities and intervals. Projected cervical cancer cases, deaths, colposcopies, screens, costs, and incremental cost-effectiveness were evaluated. We performed sensitivity analyses for hpv dna test costs.

Results

Compared with triennial cytology from age 25, 5-yearly hpv dna screening alone from age 30 resulted in equivalent incident cases and deaths, but 55% (82,000) fewer colposcopies and 43% (1,195,000) fewer screens. At hpv dna screening intervals of 3 years, whether alone or in an age-based sequence with cytology, screening costs are greater, but at intervals of more than 5 years, they are lower. Scenarios on the cost-effectiveness frontier were hpv dna testing alone every 10, 7.5, 5, or 3 years, and triennial cytology starting at age 21 or 25 when combined with hpv dna testing every 3 years.

Conclusions

Changing from cytology to hpv dna testing as the primary screening test for cervical cancer would be an acceptable strategy in Canada with respect to incidence, mortality, screening and diagnostic test volumes.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, cervical cancer, screening, cytology, hpvdna, modelling, Canada

INTRODUCTION

Since the introduction of cervical cancer (cc) screening by Pap smear cytology the 1950s, Canada has experienced a decline in cc mortality, achieving one of the lowest rates in the world1,2.

In Canada and around the world, discussion about changing from cytology to human papillomavirus (hpv) dna testing as the primary screening modality for cc is ongoing3. Compared with cytology, the hpv dna test has demonstrated greater sensitivity in the detection of high-grade cc precursor lesions and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, leading some groups to recommend its use as a primary screening modality in conjunction with cytology (co-testing) or with secondary cytology triage4–6. A recent meta-analysis of four large randomized controlled trials concluded that primary hpv dna testing is superior to cytology in lowering the incidence of cc7. The Netherlands and Australia were among the first countries to announce a switch to primary hpv dna testing for cc screening8, and several others (England, Scotland, Italy) are in the process of conducting pilot studies9,10,a. Canadian provinces and territories do not currently fund primary hpv dna testing for cc screening, and only a few fund the hpv dna test as secondary triage for results indicating atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance3.

In addition to the discussion about primary screening modality, organized screening programs worldwide show variability with respect to initiation age, stop age, and screening interval. In Europe, several countries start cc screening at later ages and use longer intervals than Canada does. For example, in Finland and the Netherlands, whose cc rates are comparable to those in Canada, cytology screening has been offered at 5-year intervals to women beginning at age 3011–13. In 2013, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (ctfphc) recommended routine screening for women 30–69 years of age, with weaker recommendations to routinely screen women 25–29 years of age. The ctfphc did not recommend routine screening of women less than 25 years of age or more than 70 years of age1. As health care practitioners transition to those relatively recent recommendations, screening is currently offered from age 21 in most Canadian provinces and territories3. The ctfphc did not make a recommendation on hpv testing, concluding that the evidence at the time was insufficient2.

As the provinces and territories move to incorporate the evolving standards and new technologies for cc screening, we used the Cancer Risk Management Model (crmm) to evaluate, in the Canadian context, the clinical and cost effectiveness of various strategies of primary cytology and hpv dna testing.

METHODS

The crmm is a Web-based microsimulation tool used to inform cancer control decision-making in Canada. The model draws on multiple data sources and expert opinion for standard disease-specific diagnostic and treatment practices, health care costs and utilities, expected personal income, and tax revenue14–16. The model performs simulations at the individual level over a specified lifespan and provides projections for national and provincial cancer control interventions. The cc and hpv transmission submodels were developed by a multidisciplinary team led by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer in collaboration with Statistics Canada. The submodels are described in detail by Miller and colleagues11, with calibration and evaluation results additionally provided by Miller and colleagues11 and by Evans and colleagues15.

We used the crmm to determine the health and economic effects of switching from cytology to hpv dna testing in various cc screening strategies for the years 2016–2046. Against a background of a pan-Canadian vaccination program, variations in the age of screening onset, the screening interval, and the primary screening modality are assessed against a reference scenario based on recommended practice: triennial cytology screening from age 25 to age 65. We project results for the year 2046, in which the Canadian population is estimated to be 41 million, with slightly more than half being women and girls.

Here, we report selected outcomes—cc incidence, mortality, and number of colposcopies and cc screens—for a set of screening scenarios involving various age-related patterns of cytology and hpv dna screening tests. The number of cc screens includes cytology samples taken and read, or hpv dna tests sampled and interpreted, or both, as appropriate. We also report screening and treatment costs, health-related quality-adjusted life-years (qalys) and incremental cost effectiveness ratios (icers). Costs reported for the year 2046 are expressed as an average of the costs in years 2044–2048 and are undiscounted. Costs and qalys used for the estimation of icers are discounted at 3%. All costs are expressed in 2008 Canadian dollars.

The icer is a ratio of the change in total cost to the change in qalys between two scenarios (calculated here over the lifetime of the simulated population). For ease of interpretation, the icers were calculated relative to the least costly scenario and also sequentially. Sequential icers indicate the incremental cost per qaly for adopting the next-more-expensive non-dominated scenario. Because the cost of hpv dna testing is uncertain, sensitivity analyses were used to explore the effects of varying the kit acquisition and the interpretation and laboratory cost components of the testing cost.

Underlying Assumptions

We assumed that hpv vaccination would underlie all scenarios, with vaccination for 12-year-old girls beginning in 2008. A 3-dose schedule of quadrivalent vaccine was used, at an assumed cost of $500. It was assumed that the program would vaccinate 70% of the target population and that vaccine efficacy would be 100%, not waning over time. The assumed cytology cost was $59.49, comprising provider consultation, tray, and lab interpretation fees costing $33.70, $10.99, and $14.80 respectively. We used $87.70 as the cost of hpv dna testing, which included consultation, tray, and kit with lab interpretation fees costing $33.70, $10.99, and $43.10 respectively (Table i).

TABLE I.

Parameters and assumptions, 2008 Canadian dollarsa

| Parameter | Assumption |

|---|---|

| Model baseline | |

| Cases simulated (n) | 32,000,000 |

| HPV vaccination coverage (% girls and women) | 70 |

| HPV vaccine cost per 3-dose course (2008 CA$) | 500 |

| Cytology cost (2008 CA$) | |

| Consultation fee | 33.70 |

| Tray fee | 10.99 |

| Lab interpretation fee | 14.80 |

| TOTAL | 59.49 |

| HPV DNA cost (2008 CA$) | |

| Consultation fee | 33.70 |

| Tray fee | 10.99 |

| Kit and lab interpretation fee | 43.10 |

| TOTAL | 87.79 |

| Additional cost assumptions | |

| Cytology screenb | |

| Regular cytology screen as follow-up for normal results | 59.49 |

| Cytology for reassessment of abnormal results | 59.49 |

| Colposcopy | |

| Initial colposcopy (without biopsy) | 955.71 |

| Reassessment colposcopy within 6 months (without biopsy) | 724.00 |

| Reassessment colposcopy not within 6 months (without biopsy) | 656.23 |

| Biopsy | 102.71 |

| HPV DNA testc | |

| When recent (≤6 months) liquid sample already exists (after liquid-based cytology) | 87.79 |

| When recent (≤6 months) liquid sample does not exist (after conventional cytology) | 87.79 |

| Observation (do nothing) | 0 |

| Cold knife | 1851.23 |

| Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) | 1887.19 |

| Cryosurgeryd | 1887.19 |

| Laserd | 1887.19 |

| Hysterectomy | 3068.01 |

| Wart removal | 190.00 |

Sources: Ontario, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Newfoundland and Labrador fee guides and expert opinion. All costs presented in 2008 Canadian dollars.

Costs are assumed to be the same for the conventional or the liquid-based method (no information to vary cost by method).

One of the two costs is chosen depending on the cytology method used (liquid versus conventional).

Simplifying assumption: assumed same cost as LEEP.

HPV = human papillomavirus.

Scenario Assumptions

We examined 14 scenarios, varying the primary screening modality and intervals:

■ Cytology only—2 scenarios from age 21 or 25 until age 65

■ hpv dna testing only—4 scenarios from age 30 to age 65 at intervals of 3, 5, 7.5, and 10 years

■ Combined cytology and hpv dna testing [in an age-based sequence (abs)]—8 scenarios with cytology for women less than 30 years of age starting at age 21 or 25, and hpv dna testing for women from age 30 to age 65 at intervals of 3, 5, 7.5, and 10 years (Table ii)

TABLE II.

Scenarios modelled

| Primary screening test | Age (years) | Interval (years) | Scenario name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Start | End | |||

| Cytology | 21 | 65 | 3 | Cytology (21×3) |

| Cytology | 25 | 65 | 3 | Cytology (25×3) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 3 | HPV (30×3) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 5 | HPV (30×5) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 7.5 | HPV (30×7.5) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 10 | HPV (30×10) |

| Cytology, | 21 | 29 | 3 | ABS (21×3; 30×3) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 3 | |

| Cytology, | 21 | 29 | 3 | ABS (21×3; 30×5) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 5 | |

| Cytology, | 21 | 29 | 3 | ABS (21×3; 30×7.5) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 7.5 | |

| Cytology, | 21 | 29 | 3 | ABS (21×3; 30×10) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 10 | |

| Cytology, | 25 | 29 | 3 | ABS (25×3; 30×3) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 3 | |

| Cytology, | 25 | 29 | 3 | ABS (25×3; 30×5) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 5 | |

| Cytology, | 25 | 29 | 3 | ABS (25×3; 30×7.5) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 7.5 | |

| Cytology, | 25 | 29 | 3 | ABS (25×3; 30×10) |

| HPV DNA | 30 | 65 | 10 | |

HPV = human papillomavirus; ABS = age-based sequential screening.

For our modelled screening programs, women were recruited beginning in 2016. Historical screening program outcomes (1955–2015) were captured in the model. Depending on the scenario, women between 21 years of age and 65 years of age were eligible for screening. The eligible age for cytology screening was set at either 21–65 or 25–65 in the cytology-only scenarios and either 21–29 or 25–29 in the cytology portion of abs screening. We assumed 3-year intervals for cytology screening regardless of scenario. For scenarios that included hpv dna screening, women 30–65 years of age were eligible for screening, and intervals were varied (3, 5, 7.5, or 10 years). The screening participation and rescreen rates were 90% and 80% respectively for all scenarios. The follow-up protocol depended on the primary screening modality. The follow-up protocol for the cytology test was based on current practice, without secondary hpv dna use for triage or otherwiseb; the follow-up protocol for the hpv dna test was based on the Ontario guideline as described by Murphy and colleagues17. Because triennial cytology for women 25–65 years of age reflects recommended practice1, we used that scenario as the reference against which other modelled scenarios were compared.

Sensitivity Analyses

We chose to examine the effect of cost variations in the hpv dna test for 2 abs scenarios that allow for cytology screening of women less than 30 years of age (the practice in Canada), recognizing that hpv dna testing in this group results in high rates of hpv positivity because of transient infections and is thus not used18,19. The cost variations were based on lab costs being

■ the same as cytology (a total cost of $59.49).

■ 25% of retail-price testing ($66.24).

■ 50% of retail-price testing ($87.79).

■ 100% of retail-price testing ($130.88).

The default cost of the analysis was $87.79.

RESULTS

Health Outcomes, Resource Utilization, and Costs

Compared with the reference scenario (triennial cytology starting at age 25), hpv dna screening every 3 years from age 30, alone or in abs with cytology starting at age 21 or 25, lowered the number of incident cases and deaths in 2046 (Table iii). Increasing the interval to 5 years in those cases generated an equivalent number of incident cases and deaths. However, increasing the screening interval beyond 5 years resulted in increased incidence and mortality.

TABLE III.

Health and resource utilization outcomesa projected for 2046 using the Cancer Risk Management Model

| Scenario | Difference compared with reference scenario [n (%)] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Incident | Deaths | Colposcopies | Screens | |

| Cytology (25×3) | Referenceb | |||

| Cytology (21×3) | −10 (1) | −10 (1) | 15,000 (10) | 163,000 (6) |

| HPV (30×3) | −180 (12) | −70 (14) | −56,000 (37) | −194,000 (7) |

| HPV (30×5) | 1 (0) | −10 (1) | −82,000 (55) | −1,195,000 (43) |

| HPV (30×7.5) | 180 (13) | 50 (10) | −96,000 (64) | −1,619,000 (58) |

| HPV (30×10) | 330 (23) | 100 (20) | −110,000 (74) | −1,819,000 (65) |

| ABS (21×3; 30×3) | −210 (14) | −80 (16) | −19,000 (13) | 217,000 (8) |

| ABS (21×3; 30×5) | −20 (2) | −10 (3) | −45,000 (30) | −771,000 (28) |

| ABS (21×3; 30×7.5) | 140 (10) | 30 (6) | −59,000 (39) | −1,196,000 (43) |

| ABS (21×3; 30×10) | 290 (20) | 80 (17) | −72,000 (48) | −1,388,000 (50) |

| ABS (25×3; 30×3) | −200 (14) | −80 (15) | −35,000 (23) | 52,000 (2) |

| ABS (25×3; 30×5) | −20 (1) | −10 (2) | −61,000 (41) | −927,000 (33) |

| ABS (25×3; 30×7.5) | 160 (11) | 40 (7) | −74,000 (49) | −1,343,000 (50) |

| ABS (25×3; 30×10) | 300 (21) | 100 (17) | −87,000 (58) | −1,542,000 (55) |

All figures in table are rounded.

Incident cases, 1400; deaths, 500; colposcopies, 50,000; screens, 2,801,000.

HPV = human papillomavirus; ABS = age-based sequential screening.

Comparing the scenarios that used hpv dna testing alone, incident ccs rose by 23% in 2046 (n = 330) when a 10-year rather than a 5-year interval was used. Likewise, comparing the abs screening scenarios, incident cancer cases rose by 20% (n = 290) and 21% (n = 300) when a 10-year rather than a 5-year interval was used (cytology start at age 21 and age 25 respectively). The change in the number of cc deaths with a lengthened screening interval followed a similar pattern. Thus, compared with cytology only, hpv dna testing alone or combined with cytology is better or equivalent with respect to the foregoing health outcomes, provided that the length of the screening interval does not exceed 5 years.

By contrast, hpv dna testing generally resulted in health care resource utilization savings (Table iii). Compared with the reference scenario, 5-yearly hpv dna screening alone from age 30 resulted in 55% fewer colposcopies (n = 82,000) and 43% fewer screens (n = 1,195,000). In addition, abs screening starting at age 21, with 5-yearly hpv dna testing, resulted in 30% fewer colposcopies (n = 45,000) and 28% fewer screens (n = 771,000). In the scenarios using hpv dna testing only, absolute colposcopy and screen counts declined as the screening interval increased. Compared with the reference scenario, scenarios involving lengthened intervals produced increasingly larger differences in colposcopy and screen counts. The patterns were similar in the abs scenarios.

The foregoing scenarios also led to a reduction in total undiscounted costs. Compared with the reference scenario, 5-yearly hpv dna testing reduced costs by 24% ($106 million), and abs starting at age 21 with 5-yearly hpv dna testing reduced costs by 10% ($42 million). As screening intervals for hpv dna testing increased, cost reductions relative to the reference scenario concomitantly increased. With 10-yearly intervals for hpv dna testing, cost reductions were 42% for hpv dna alone, 27% for abs with cytology at age 21, and 33% for abs with cytology at age 25.

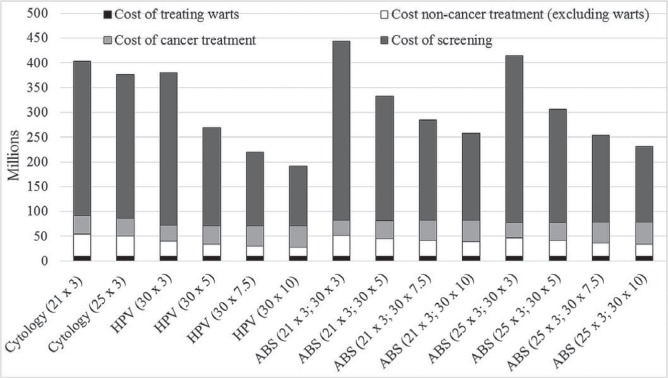

Figure 1 shows the changes in the cost composition of the scenarios (vaccination costs were not included because they were invariable). At hpv dna screening intervals of 3 years, whether alone or in an abs scenario with cytology, screening costs are greater than they are in the reference scenario. At intervals greater than 5 years, screening costs are lower than they are in the reference scenario; however, cancer treatment costs are higher.

FIGURE 1.

Cost components of screening and treatment, by screening strategy in 2046. Costs are calculated as a 5-year average of the 2044–2048 costs and are undiscounted. HPV = human papillomavirus; ABS = age-based sequential screening.

Incremental Cost-Effectiveness

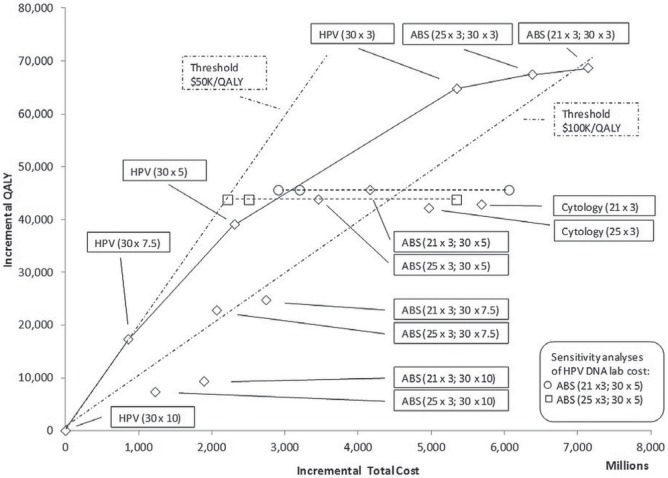

Compared with the base case (the lowest-cost scenario: hpv dna testing at 10-year intervals), the icers ranged from $49,000 per qaly to $202,000 per qaly (Table iv). When 5-yearly hpv dna testing starting at age 30 was combined with triennial cytology screening at either age 21 or 25, the cost savings and qalys increased relative to the reference scenario (triennial screening from age 25). Scenarios found on the frontier were hpv dna testing alone every 10, 7.5, 5, and 3 years, and triennial cytology starting at age 21 or 25 when combined with hpv dna testing every 3 years (Figure 2).

TABLE IV.

Incremental cost-effectiveness

| Scenario | Incremental ... a | ICER | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Cost (CA$ millions) | QALYs | Relative to lowest cost | Sequentialb | |

| HPV (30×10) | — | — | NA | NA |

| HPV (30×7.5) | 855 | 17,300 | 49,400 | 49,400 |

| ABS (25×3; 30×10) | 1,225 | 7,300 | 166,700 | Dominated |

| ABS (21×3; 30×10) | 1,893 | 9,300 | 202,500 | Dominated |

| ABS (25×3; 30×7.5) | 2,066 | 22,800 | 90,600 | Dominatedc |

| HPV (30×5) | 2,311 | 39,100 | 59,100 | 66,900 |

| ABS (21×3; 30×7.5) | 2,741 | 24,700 | 110,800 | Dominated |

| ABS (25×3; 30×5) | 3,455 | 43,800 | 78,900 | Dominatedc |

| ABS (21×3; 30×5) | 4,159 | 45,600 | 91,200 | Dominatedc |

| Cytology (25×3) | 4,966 | 42,100 | 117,800 | Dominated |

| HPV (30×3) | 5,347 | 64,700 | 82,600 | 118,300 |

| Cytology (21×3) | 5,684 | 42,800 | 132,800 | Dominated |

| ABS (25×3; 30×3) | 6,377 | 67,400 | 94,600 | 381,900 |

| ABS (21×3; 30×3) | 7,139 | 68,700 | 103,900 | 611,600 |

Discounted at 3%.

Calculated as the change in cost and QALYs from the previous non-dominated strategy.

By extended dominance.

QALY = quality-adjusted life–year; ICER = incremental cost effectiveness ratio; NA = not applicable; HPV = human papillomavirus; ABS = age-based sequential screening.

FIGURE 2.

Efficiency frontier: plot of incremental cost and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) relative to lowest-cost scenario. HPV = human papillomavirus; ABS = age-based sequential screening.

Sensitivity Analyses

The effect of varying the cost of the hpv dna testing in 2 of the abs scenarios (cytology starting at either age 21 or 25 combined with 5-yearly hpv dna testing starting at age 30) is also plotted in Figure 2. If the kit and interpretation fees for hpv dna testing were to match the fees for cytology testing ($59.49 compared with the base case cost of $87.79), abs screening could potentially result in a total discounted cost more than $1 billion less than the recommended practice scenario over the lifetime of the simulated population. Conversely, costs based on full-retail-price kit and interpretation values could potentially increase total costs by up to almost $2 billion compared with the base-case cost assumption.

Provided that hpv dna testing costs less than $106.00, the abs strategy starting at age 21, with 5-yearly hpv dna testing, dominates the reference strategy of triennial cytology starting at age 25, in the sense that the former costs less and results in more qalys than the latter. The abs strategy starting at age 25, with 5-yearly hpv dna testing, dominates the default strategy provided that hpv dna testing costs less than $122.00. At higher costs, preference for the reference strategy or the dna alternative would depend on the willingness to pay for the additional qalys resulting from abs screening. Note that similar increases or decreases for the hpv dna lab costs in the other scenarios, including hpv dna testing alone, would shift the point estimates in Figure 2 right and left respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the era of expanding hpv vaccination, cc incidence and mortality rates are expected to decline20, and the utility of Pap smear cytology as the primary screening test is being questioned. As the prevalence of cc and precursor lesions declines, the positive and negative predictive values of cytology decrease21. Testing for hpv dna, which has greater sensitivity than cytology and detects the causative agent for cc, has thus become an important tool in the armamentarium of cc screening and is becoming an alternative to cytology for primary screening. The transition to, and implementation of, new screening algorithms must be approached using the best evidence available, and modelling that incorporates the relevant information allows decision-makers to understand the various options along different time horizons. Our study shows the complex trade-offs between cost and clinical benefit in the screening scenarios presented.

Firstly, compared with screening starting at age 30, cytology screening of women less than 30 years of age did not result in an improvement in cc incidence or mortality, but did contribute to increased costs. Women less than 30 years of age have a very low incidence of and mortality from cc22, but high incidences of transient hpv infection and cervical abnormalities23, most of which resolve with time but require ongoing colposcopy visits and investigations. Delaying screening until age 30 allows for transient lesions to regress and more problematic ones to persist until a later first screen24,25. Given the prolonged natural history for hpv infection to develop into cancer26, delaying screening until age 30 does not significantly affect cc incidence or mortality22. Similarly, within the Canadian context, the HPV Focal trial in British Columbia showed that primary hpv testing starting at age 25 resulted in high rates of hpv positivity and cytologic abnormalities requiring follow-up in women less than 30 years of age18. As the vaccinated cohort of women starts screening, hpv positivity rates and cytologic abnormalities will decline27,28, making a delay in screening more acceptable.

As long as the willingness to pay for an additional qaly is less than $166,700, any abs screening incorporating triennial cytology in women less than 30 years of age would not be cost-effective relative to its pure hpv testing counterpart. With Table iv showing that scenarios involving cytology alone are dominated, model projections suggest that pure hpv testing strategies are the most attractive. Which of those strategies will be the most appealing will depend on willingness to pay.

Secondly, prior data from cervical cytology population screening show that a screening frequency greater than triennial does not significantly improve the cc incidence, but does increase the number of lifetime screens and costs29. However, increasing the screening interval beyond 5 years resulted in higher rates of cancer. Reducing the hpv dna screening interval to 3 years improves incidence and mortality outcomes and increases the number of life-years gained, but at substantial additional cost. The lowest-cost scenario of hpv dna testing every 10 years results in the least screens and colposcopies among all scenarios, but compared with the reference of triennial cytology beginning at age 25, achieves those savings at a clinical cost of a 30% increase in incident cases.

Primary hpv dna testing performed at intervals of less than 3 years is more likely to detect transient hpv infections of inconsequential risk, when it is persistent infection that is associated with an increased risk of precursor lesion and cancer development. Furthermore, compared with cytology, a negative hpv dna test result has superior negative predictive value. A negative hpv dna test is associated with an 0.27% cumulative incidence rate of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse after 6 years; the rate for women with a negative cytology result is 0.97%30. Thus, screening intervals more frequent than 5 years are not recommended for primary hpv dna testing4,13. According to our model, moving from 5-yearly to triennial hpv dna testing would cost more than $100,000 per additional qaly gained.

Our results are consistent with findings in other studies. A study by Berkhof and colleagues4 in the Netherlands used screening intervals from 5 to 10 years to examine the health and economic effects of hpv dna testing compared with cytology testing. The standard of care in that country is cytology screening every 5 years in women from age 30 to age 60. They found that changing from cytology to primary hpv dna testing with cytology triage resulted in a 23% reduction in cc cases. A reduction in cc cases was also seen when the hpv dna screening interval was extended to 7.5 years. The authors concluded that 5-yearly cytology with hpv dna triage and 5- and 7.5-yearly hpv dna testing with cytology triage were cost-effective for their base case of settings. However, their cost values were less than those in the Canadian environment, for a Dutch willingness-to-pay threshold icer of €20,000 per qaly. The costs attributed to screening tests and diagnostic colposcopy were less than those in Canada and likely reflect different values for human resources and test kits.

Because there is little enthusiasm and some scepticism for screening intervals beyond 3 years among Canadian provincial and territorial screening programs31, a scenario of cytology every 5 years was not included in our analysis. Canadian provinces and territories have also chosen not to adopt the ctfphc guidelines for a screening start age of 30 (strong recommendation) or 25 years (weak recommendation) and still offer screening from age 21 to 70. Consequently, our analysis included younger women from 21 or 25 years of age to 65 years of age, and considered scenarios with abs screening that best reflects the Canadian experience.

Similarly, a systematic review by Nahivjou and colleagues13 of cc screening strategies from an economic standpoint suggested that hpv dna testing—starting at age 30 or older, with screening intervals of 5 years or more—was the most cost-effective strategy. They also found that, in some countries, national guidelines did not match scenarios emerging from cost-effectiveness studies. Their review aligned with prior reviews of cost-effectiveness in post-vaccination high-resource settings with established screening programs. Such analyses recommend the introduction of hpv dna primary screening in high-resource settings; however, discrepancies between practice guidelines and theoretical study recommendations are observed1,8 Our study adds further support to the cost-effectiveness and health utilization benefits of a switch from cytology to primary hpv dna testing for cc screening in the Canadian context. It also illuminates the implementation considerations associated with interval lengths.

Limitations

There are some limitations to our study to consider.

In Canada, hpv dna testing has not been implemented, and thus, uncertainty related to its effectiveness in the Canadian context remains. A degree of parameter uncertainty is also present, because few empirical data about sexual behaviour, long-term vaccine efficacy, infection, and progression of vaccine and non-vaccine hpv types into cancer are available. Moreover, because of an expectedly reduced incidence of cc and its precursor lesions after vaccination, with an associated lower volume of positive smears, uncertainty surrounds the future performance of cytology with respect to detection of such lesions, whether cytology is used as a primary or secondary test. Our analysis is thus limited because the uncertainty surrounding the model outcomes is not reported. The model generates a combined uncertainty from parameter uncertainty and Monte Carlo error.

Our scenarios used age 65 as the stop age for screening; however, women are living longer, well into their 80s, and the benefit of screening beyond age 65 or 70 is controversial32,33. The Ontario primary hpv dna test protocol for screening was used, but other algorithms—such as that used in the HPV Focal study—might yield different results in costs and clinical outcomes.

For our scenarios, vaccination costs were kept constant at the full retail price for 3 doses, with a vaccine efficacy of 100% for the full duration. A change in price, variation in dosing (2 vs. 3 doses), and waning efficacy or efficacy duration could affect total screening and treatment costs. A change in vaccine efficacy duration and effectiveness would affect screening outcomes, as would altering the proportion of women vaccinated.

Lastly, the crmm submodel does not yet take into account the potential effects of health-related quality of life from screening and subsequent diagnostic tests—for example, the physical and psychological harms from false-positive results and follow-up of innocuous lesions, or the reproductive effects after cc precursor treatments34. There is also a concern that if screening is delayed to age 30, women might not avail themselves of other beneficial gynecologic care traditionally associated with screening, such as contraceptive and sexual health counselling.

CONCLUSIONS

According to projections from the crmm, changing from cytology to hpv dna testing as the primary screening test for cc could be an acceptable strategy with respect to incidence, mortality, and screening and diagnostic test volumes. Compared with cytology every 3 years for women 21–65 years of age, hpv dna testing every 5 years for women 30–65 years of age is at least as effective with respect to clinical incidence and mortality outcomes, resource utilization, and costs. Screening strategies incorporating hpv dna testing for primary screening were found to be more efficient than cytology-only screening strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This analysis is based on the crmm maintained by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. The crmm is made possible by a financial contribution from Health Canada through the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. The hpv transmission model was initially developed using information available in the technical appendix of Van de Velde and colleagues35 and input from Marc Brisson. We also acknowledge the contribution of a large number of other individuals who have been involved in the making of the crmm (see http://www.cancerview.ca/crmmacknowledgements). The cc and hpv transmission models are freely available. Interested users can access them at http://www.cancerview.ca/cancerriskmanagement after completion of a straightforward registration process.

Footnotes

For the United Kingdom, see http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/cervical/hpv-primary-screening.html and http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Cervical-screening-test/Pages/Results.aspx.

CRMM version 2.2 at http://www.cancerview.ca/cancerrisk management.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dickinson J, Tsakonas E, Conner Gorber S, et al. on behalf of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care Recommendations on screening for cervical cancer. CMAJ. 2013;185:35–45. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.113-2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickinson JA, Stankiewicz A, Popadiuk C, Pogany L, Onysko J, Miller AB. Reduced cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Canada: national data from 1932 to 2006. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:992. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (cpac) Cervical Cancer Screening in Canada: Monitoring Program Performance 2009–2011. Toronto, ON: CPAC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkhof J, Coupé VM, Bogaards JA, et al. The health and economic effects of hpv dna screening in the Netherlands. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2147–58. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on hpv testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095–101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. on behalf of the Canadian Cervical Cancer Screening Trial Study Group Human papillomavirus dna versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, et al. on behalf of the International HPV Screening Working Group Efficacy of hpv-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendes D, Bains I, Vanni T, Jit M. Systematic review of model-based cervical screening evaluations. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:334. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1332-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasquale L, Giorgi Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al. Cervical cancer screening with hpv testing in the Valcamonica (Italy) screening programme. J Med Screen. 2015;22:38–48. doi: 10.1177/0969141314561707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennet N. UK pilot of hpv primary screening for cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e288. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70254-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller AB, Gribble S, Nadeau C, et al. Evaluation of the natural history of cancer of the cervix, implications for prevention. The Cancer Risk Management Model (crmm)—human papillomavirus and cervical components. J Cancer Policy. 2015;4:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2015.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Habbema D, De Kok IM, Brown ML. Cervical cancer screening in the United States and the Netherlands: a tale of two countries. Milbank Q. 2012;90:5–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahvijou A, Hadji M, Marnani AB, et al. A systematic review of economic aspects of cervical cancer screening strategies worldwide: discrepancy between economic analysis and policymaking. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8229–37. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.19.8229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzgerald NR, Flanagan WM, Evans WK, Miller AB, on behalf of the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer Cancer Risk Management Lung Cancer Working Group Eligibility for low-dose computerized tomography screening among asbestos-exposed individuals. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2015;41:407–12. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans W, Wolfson MC, Flanagan WM, et al. Canadian cancer risk management model: evaluation of cancer control. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29:131–9. doi: 10.1017/S0266462313000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flanagan W, Evans WK, Fitzgerald NR, Goffin JR, Miller AB, Wolfson MC. Performance of the cancer risk management model lung cancer screening module. Health Rep. 2014;26:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy J, Kennedy E, Dunn S, et al. Cervical Screening. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coldman AJ, Phillips N, van Niekerk D, et al. Projected impact of hpv and lbc primary testing on rates of referral for colposcopy in a Canadian cervical cancer screening program. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:412–20. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiffman M, Solomon D. Findings to date from the ascus-lsil Triage Study (alts) Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:946–9. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-946-FTDFTA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van de Velde N, Brisson M, Boily MC. Modeling human papillomavirus vaccine effectiveness: quantifying the impact of parameter uncertainty. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:762–75. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franco EL, Cuzick J, Hildesheim A, de Sanjose S. Chapter 20: issues in planning cervical cancer screening in the era of hpv vaccination. Vaccine. 2006;24(suppl 3):S3/171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popadiuk C, Stankiewicz A, Dickinson J, Pogany L, Miller AB, Onysko J. Invasive cervical cancer incidence and mortality among Canadian women aged 15 to 29 and the impact of screening. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:1167–76. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anttila A, Pukkala E, Soderman B, Kallio M, Nieminen P, Hakama M. Effect of organised screening on cervical cancer incidence and mortality in Finland, 1963–1995: recent increase in cervical cancer incidence. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:59–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990924)83:1<59::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moscicki AB, Ma Y, Wibbelsman C, et al. Rate of and risks for regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1373–80. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fe777f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrett LD, Frood J, Nishri D, Ugnat AM, on behalf of the Cancer in Young Adults in Canada Working Group Cancer incidence in young adults in Canada: preliminary results of a cancer surveillance project. Chronic Dis Can. 2002;23:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burd EM. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:1–17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.1-17.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brotherton JM, Fridman M, May CL, Chappell G, Saville AM, Gertig DM. Early effect of the hpv vaccination programme on cervical abnormalities in Victoria, Australia: an ecological study. Lancet. 2011;377:2085–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60551-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, Kaldor JM, et al. Fall in human papillomavirus prevalence following a national vaccination program. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1645–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Screening for squamous cervical cancer: duration of low risk after negative results of cervical cytology and its implication for screening policies. iarc Working Group on Evaluation of Cervical Cancer Screening Programmes. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:659–64. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6548.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P, et al. Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a1754. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickinson JA, Miller AB, Popadiuk C. When to start cervical screening: epidemiological evidence from Canada. BJOG. 2014;121:255–60. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dinkelspiel H, Fetterman B, Poitras N, et al. Screening history preceding a diagnosis of cervical cancer in women age 65 and older. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:203–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rositch AF, Silver MI, Gravitt PE. Cervical cancer screening in older women: new evidence and knowledge gaps. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin-Hirsch P, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E. Obstetric outcomes after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;367:489–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van de Velde N, Brisson M, Boily MC. Understanding differences in predictions of hpv vaccine effectiveness: a comparative model-based analysis. Vaccine. 2010;28:5473–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]