Significance

Intelligence presents evolutionary biology with one of its greatest challenges. It has long been thought that species with relatively large brains for their body size are more intelligent. However, despite decades of research, the idea that brain size predicts cognitive abilities remains highly controversial; little experimental support exists for a relationship between brain size and the ability to solve novel problems. We presented 140 zoo-housed members of 39 mammalian carnivore species with a novel problem-solving task and found that the species’ relative brain sizes predicted problem-solving success. Our results provide important support for the claim that brain size reflects an animal’s problem-solving abilities and enhance our understanding of why larger brains evolved in some species.

Keywords: brain size, problem-solving, carnivore, social complexity, intelligence

Abstract

Despite considerable interest in the forces shaping the relationship between brain size and cognitive abilities, it remains controversial whether larger-brained animals are, indeed, better problem-solvers. Recently, several comparative studies have revealed correlations between brain size and traits thought to require advanced cognitive abilities, such as innovation, behavioral flexibility, invasion success, and self-control. However, the general assumption that animals with larger brains have superior cognitive abilities has been heavily criticized, primarily because of the lack of experimental support for it. Here, we designed an experiment to inquire whether specific neuroanatomical or socioecological measures predict success at solving a novel technical problem among species in the mammalian order Carnivora. We presented puzzle boxes, baited with food and scaled to accommodate body size, to members of 39 carnivore species from nine families housed in multiple North American zoos. We found that species with larger brains relative to their body mass were more successful at opening the boxes. In a subset of species, we also used virtual brain endocasts to measure volumes of four gross brain regions and show that some of these regions improve model prediction of success at opening the boxes when included with total brain size and body mass. Socioecological variables, including measures of social complexity and manual dexterity, failed to predict success at opening the boxes. Our results, thus, fail to support the social brain hypothesis but provide important empirical support for the relationship between relative brain size and the ability to solve this novel technical problem.

Animals exhibit extreme variation in brain size, with the sperm whale’s brain weighing up to 9 kg (1), whereas the brain of the desert ant weighs only 0.00028 g (2). Although body mass is the single best predictor of brain size (1, 3), some species have much larger brains than expected given their body size (e.g., humans and dusky dolphins), whereas other species have much smaller brains than expected (e.g., hippopotamus and blue whale) (1). Brain tissue is energetically costly (4–6), and therefore, large brains are presumed to have been favored by natural selection, because they confer advantages associated with enhanced cognition (3). However, despite great interest in the determinants of brain size, it remains controversial whether brain size truly reflects an animal’s cognitive abilities (7–9).

Several studies have found an association between absolute or relative brain size and behaviors thought to be indicative of complex cognitive abilities. For example, brain size has been found to correlate with bower complexity in bower birds (10), success at building food caches among birds (11), numerical abilities in guppies (5), and two measures of self-control in a comparative study of 36 species of mammals and birds (12). Additionally, larger-brained bird species have been found to be more innovative, more successful when invading novel environments, and more flexible in their behavior (13–16). Although there is circumstantial evidence suggesting an association between problem-solving ability and brain size, experimental evidence is extremely rare. To experimentally assess the relationship between brain size and any cognitive ability across a number of species in a standardized way is challenging because of the unique adaptations each species has evolved for life in its particular environment (17). In this study, we investigate whether larger-brained animals do, indeed, exhibit enhanced problem-solving abilities by conducting a standardized experiment in which we present a novel problem-solving task to individuals from a large array of species within the mammalian order Carnivora.

Carnivores often engage in seemingly intelligent behaviors, such as the cooperative hunting of prey (18, 19). Nevertheless, with the exception of domestic dogs, carnivores have largely been ignored in the animal cognition literature (20). Mammalian carnivores comprise an excellent taxon in which to assess the relationship between brain size and problem-solving ability and test predictions of hypotheses forwarded to explain the evolution of large brains and superior cognitive abilities, because they exhibit great variation in their body size, their brain size relative to body size, their social structure, and their apparent need to use diverse behaviors to solve ecological problems. Although most carnivores are solitary, many species live in cohesive or fission–fusion social groups that closely resemble primate societies (21–23). Furthermore, experiments with both wild spotted hyenas (24) and wild meerkats (25) show that members of these species are able to solve novel problems, and in spotted hyenas, those individuals that exhibit the greatest behavioral diversity are the most successful problem-solvers (24).

Here, we presented steel mesh puzzle boxes, scaled according to subject body size, to 140 individuals from 39 species in nine families of zoo-housed carnivores and evaluated whether individuals in each species successfully opened the boxes to obtain a food reward inside (Fig. 1A and Dataset S1). In addition to testing whether larger-brained carnivores are better at solving a novel technical problem, we inquired whether species that live in larger social groups exhibit enhanced problem-solving abilities compared with species that are solitary or live in smaller social groups. We also asked whether species exhibiting greater behavioral diversity are better at solving problems than species exhibiting less behavioral diversity. Additionally, carnivores exhibit an impressive range of manual dexterity from the famously dexterous raccoons and coatis to the much less dexterous hyenas and cheetahs (26). Therefore, to ensure that our measure of problem-solving ability was not solely determined by manual dexterity and ensure that our problem-solving test was equivalently difficult across a range of species, we also examined the impact of manual dexterity on problem-solving success in this study.

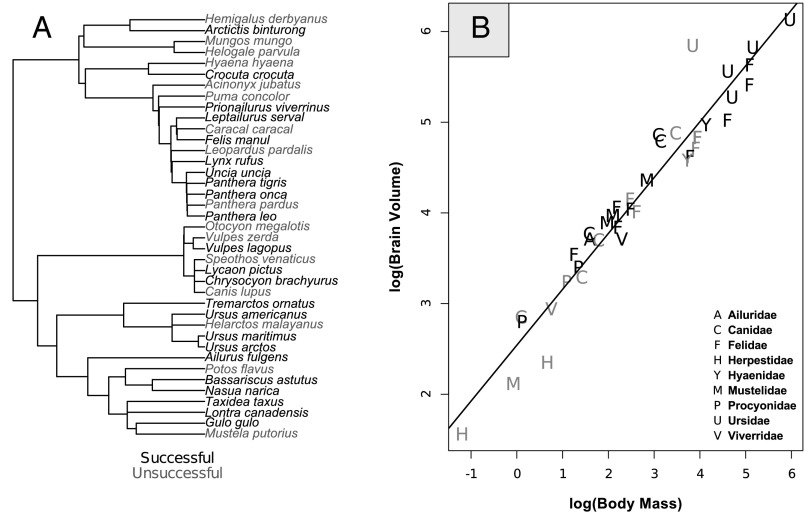

Fig. 1.

(A) We tested the performance of zoo-housed individuals in 39 species from nine carnivore families by exposing them to our puzzle box problem, with the box scaled to accommodate body size. (B) The relationship between body mass (kilograms) and brain volume (milliliters) in 39 mammalian carnivore species. (A) Species in gray and (B) family names in gray represent species in which no tested subjects opened the box. Note that, in B, two species in the family Felidae (Panthera pardus and Puma concolor) have overlapping points.

Finally, the relative sizes of specific brain regions might be more strongly predictive of problem-solving ability than overall brain size relative to body size. Recently, Swanson et al. (27) used virtual brain endocasts to show that, although mammalian carnivore species with a higher degree of social complexity did not have larger total brain volumes relative to either body mass or skull size, they did have significantly larger cerebrum volumes relative to total brain volume. Therefore, we used deviance information criterion (DIC) model selection analysis to inquire whether any of four gross regional brain volumes (total cerebrum, posterior cerebrum, anterior cerebrum, and hindbrain) better predicted performance in our puzzle box trials than total brain size in a subset of 17 carnivore species for which these data were available from virtual brain endocasts (Dataset S1).

We retrieved data on brain size and the sizes of gross brain regions from published literature and used phylogenetic comparative statistics to assess relationships among these measures, social complexity, behavioral diversity, manual dexterity, and performance measures obtained during box trials. We used social group size as our proxy for social complexity, because in an earlier comparative study of mammalian carnivores, Swanson et al. (27) found that group size was just as effective of a proxy as the first axis from a principal component analysis of several different measures of social complexity in carnivores. We used an established measure of behavioral diversity, which we obtained by calculating the number of different behaviors exhibited by individuals from each species while interacting with the puzzle box (24, 28–30). To assess manual dexterity, we recorded occurrences of 20 types of forelimb movements following the work by Iwaniuk et al. (26). Finally, we used measures taken from virtual brains to analyze the effects of the size of specific gross brain regions on performance in puzzle box trials. These measures allowed us to inquire whether specific neuroanatomical or socioecological measures can help explain variation in problem-solving ability across species.

Results

We tested one to nine individuals in each of 39 species (mean = 4.9 individuals; median = 5) (Table S1). Of 140 individuals tested, 49 individuals (35%) from 23 species succeeded at opening the puzzle box (Fig. 1A, Table S1, and Movie S1). The proportion of individuals within each species that succeeded at opening the box varied considerably among families, with species in the families Ursidae (69.2% of trials), Procyonidae (53.8% of trials), and Mustelidae (47.1% of trials) being most successful at opening the puzzle box and those within the family Herpestidae (0%) being the least successful (Table S1). Total brain volume corrected for body mass varied among the species that we tested, with Canid and Ursid species having the largest brains for their body mass and Viverrid, Hyaenid, and Herpestid species having the smallest brains for their body mass (Fig. 1B and Table S1).

Table S1.

Summary of the number of mammalian carnivore species and different individuals within each species in which we examined their performance in opening up the puzzle box

| Family | No. of species | Relative brain size | Total no. of trials | No. of individuals tested | No. of individuals successful | Individuals successful (%) |

| Ailuridae | 1 | 0.189 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 25 |

| Canidae | 7 | 0.193 (−0.13–0.41) | 75 | 25 | 6 | 24 |

| Felidae | 13 | −0.093 (−0.36–0.23) | 179 | 52 | 15 | 28.8 |

| Herpestidae | 2 | −0.417 (−0.59 to −0.24) | 15 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyaenidae | 2 | −0.192 (−0.26 to −0.12) | 23 | 7 | 2 | 28.6 |

| Mustelidae | 4 | −0.005 (−0.37–0.14) | 81 | 17 | 8 | 47.1 |

| Procyonidae | 3 | 0.077 (0.02–0.18) | 42 | 13 | 7 | 53.8 |

| Ursidae | 5 | 0.196 (−0.16–0.94) | 45 | 13 | 9 | 69.2 |

| Viverridae | 2 | −0.153 (−0.24 to −0.06) | 17 | 4 | 1 | 25 |

| Sum or mean | 39 | — | 495 | 140 | 49 | 35 |

Relative brain size (mean and range) for each family is the residual brain volume from a general linear model containing log-transformed brain volume (kilograms) as the response variable and log-transformed brain volume (endocranial volume in milliliters) as the predictor variable and is for presentation purposes only.

It appeared that the majority of subjects in our study actually gained an understanding of the puzzle and how to open it. If individuals were only using brute force to open the box or emitting exploratory behaviors without any understanding of how the puzzle works, then we should not have seen any evidence of learning the solution over time. To investigate whether the test subjects were actually learning the solution to the problem, we ran a nonphylogenetically corrected generalized linear mixed-effects model to examine how work time changed over successive trials for successful individuals. Work time significantly decreased as trial number increased (F9,97 = 2.57; P = 0.01), indicating that successful individuals improved their performance with experience.

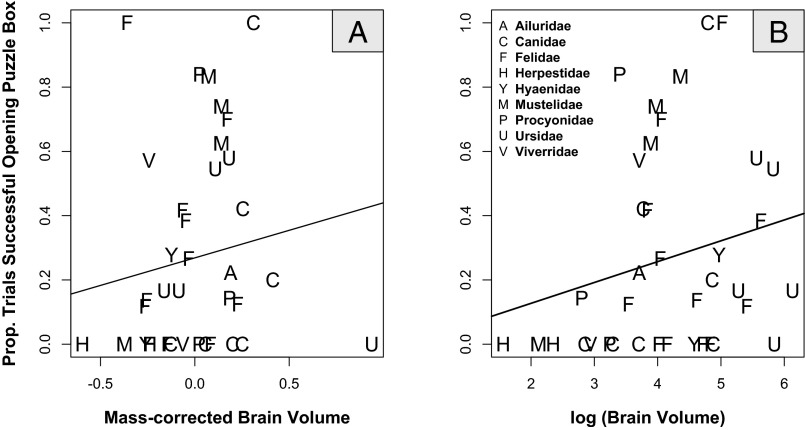

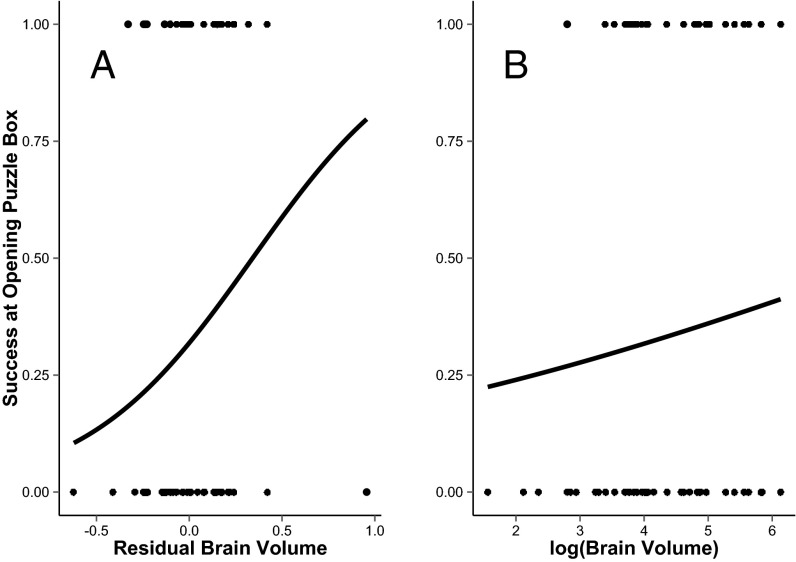

The top model based on DIC model selection was one that contained brain volume, body mass, latency to approach the puzzle box, time spent trying to open the box, manual dexterity, behavioral diversity, and group size (Table 1). The only statistically indistinguishable model (i.e., ΔDIC < 2) did not include group size but was otherwise the same (Table 1). Individuals from carnivore species with both larger absolute brain volumes and larger brain volumes relative to their overall body mass were better than others at opening the puzzle box, but only relative brain volume was a statistically significant predictor [P value from Markov Chain Monte Carlo (pMCMC) = 0.013] (Figs. 2 and 3, Table 2, and Table S2). Our results were insensitive to variation in both the total number of individuals tested per species and the minimum number of trials conducted per individual. Specifically, we obtained the same qualitative results if we limited our analyses to only species in which at least three (398 trials on 112 individuals from 23 species) (Table S3) or four individuals (348 trials on 97 individuals from 18 species) (Table S4) were tested per species, and if we restricted our analyses only to individuals to which we administered at least three separate trials (total number of trials per individual was 3–10) (Table S5). Additionally, if we restricted our analyses only to trials 1–3 for individuals that were tested at least three times (388 trials with 39 species), we found that individuals from species with a larger brain volume for their body mass tended to be more likely to open the puzzle box (pMCMC = 0.052) (Table S6).

Table 1.

Model comparisons using DIC model selection analysis to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 39 carnivore species

| Fixed effects | λ-Posterior mode | λ-Mean (95% credible interval) | DIC | ΔDIC |

| BV + BM + L + WT + D + BD + GS | 0.94 | 0.85 (0.49–0.99) | 283.2 | 0 |

| BV + BM + L + WT + D + BD | 0.93 | 0.82 (0.33–0.99) | 284.9 | 1.7 |

| L + WT + D + BD + GS | 0.95 | 0.87 (0.62–0.99) | 286.4 | 3.2 |

| L + WT + D + BD | 0.96 | 0.85 (0.56–0.99) | 288.5 | 5.3 |

| WT + D + BD | 0.93 | 0.84 (0.54–0.99) | 288.5 | 5.3 |

| BV + BM + L + GS | 0.97 | 0.91 (0.76–0.99) | 293.3 | 10.1 |

| BV + BM + L | 0.95 | 0.88 (0.65–0.99) | 294.3 | 11.1 |

| BV + BM + GS | 0.98 | 0.91 (0.73–0.99) | 294.5 | 11.3 |

| L + GS | 0.97 | 0.92 (0.78–0.99) | 296.4 | 13.2 |

| BV + BM | 0.96 | 0.88 (0.65–0.99) | 296.6 | 13.4 |

| GS | 0.97 | 0.91 (0.73–0.99) | 298.1 | 14.9 |

| Intercept | 0.96 | 0.90 (0.71–0.99) | 299.9 | 16.7 |

Model terms are behavioral diversity (BD), body mass (BM), brain volume (BV), dexterity (D), group size (GS), latency to approach puzzle box (L), and time spent working trying to open the puzzle box (WT).

Fig. 2.

(A) Carnivore species with larger brain volumes for their body mass were better than others at opening the puzzle box. (B) There was no significant relationship between absolute brain volume and success at opening the puzzle box in carnivore species when body mass was excluded from the statistical model. Data presented represent the average proportion of puzzle box trials in which species were successful and are for presentation purposes only, whereas statistical results from our full model used for our inferences are shown in Table 2. Mass-corrected brain volume in A is from a general linear model and for presentation purposes only; statistical results from the full model are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

(A) Individuals from carnivore species with larger brain volumes relative to their body mass were significantly better than others at opening the puzzle box (Table 2). (B) There was no significant relationship between absolute brain volume and success at opening the puzzle box in our individual-level analyses in which body mass was excluded (Table S2). Individuals with success equal to one opened the box, whereas those with success equal to zero did not. Mass-corrected brain volume in A is from a general linear model and for presentation purposes only; full statistical results are shown in Table 2 and Table S2. Regression lines represent predicted relationships from statistical models investigating the association between (A) brain volume relative to body mass or (B) log (brain volume) and success at opening the puzzle box.

Table 2.

Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed-effects models to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 39 mammalian carnivore species

| Effective sample size | Posterior mean (95% CI) | Posterior mode | pMCMC | |

| Random effect | ||||

| Species | 3,094 | 13.8 (0.0007–40.4) | 4.3 | — |

| Individual identification | 2,791 | 21 (7.6–38.2) | 16.1 | — |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept* | 3,284* | −36.5 (−60.7 to −16.1)* | −30.6* | 0.0003* |

| Brain volume* | 3,284* | 8.5 (1.3–16.3)* | 7.8* | 0.013* |

| Body mass* | 3,720* | −4.6 (−9.2 to −0.2)* | −4.9* | 0.036* |

| Latency to approach | 3,284 | −0.12 (−0.5–0.3) | −0.1 | 0.57 |

| Work time | 2,493 | 0.34 (−0.04–0.7) | 0.4 | 0.08 |

| Behavioral diversity | 3,018 | 1.7 (−1.9–6) | 1.2 | 0.39 |

| Dexterity | 3,284 | 2.7 (−0.3–5.8) | 2.2 | 0.08 |

| Group size | 3,284 | −0.04 (−0.3–0.2) | −0.02 | 0.79 |

pMCMC is the Bayesian P value. Sample sizes are 495 trials on 140 individuals from 39 different species. 95% CI, 95% credible interval.

Statistically significant.

Table S2.

Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed effects models to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 39 mammalian carnivore species

| Fixed or random effect | Effective sample size | Posterior mean (95% CI) | Posterior mode | pMCMC |

| Random effect | ||||

| Species | 2,263 | 20.9 (0.001–56.5) | 8.2 | — |

| Individual identification | 2,617 | 19.3 (6.3–34.5) | 14.1 | — |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept | 2,617 | −18.3 (−30.4 to −7.8) | −18.2 | 0.0004 |

| Brain volume | 2,617 | 1.4 (−0.6–3.4) | 1.2 | 0.14 |

| Latency to approach | 2,617 | −0.14 (−0.5–0.2) | −0.1 | 0.52 |

| Work time | 2,713 | 0.3 (−0.06–0.7) | 0.3 | 0.09 |

| Behavioral diversity | 2,617 | 1.3 (−2.5–5.7) | 1.2 | 0.52 |

| Dexterity | 2,617 | 2.7 (−0.4–6.1) | 2.5 | 0.07 |

| Group size | 2,617 | −0.09 (−0.4–0.2) | −0.08 | 0.54 |

This model investigates the effect of absolute brain volume without body mass in the model (Table 2 shows the same model including body mass). pMCMC is the Bayesian P value. Sample sizes are 495 trials on 140 individuals from 39 different species.

Table S3.

Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed-effects models to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 23 mammalian carnivore species when at least three individuals were tested in each species

| Fixed or random effect | Effective sample size | Posterior mean (95% CI) | Posterior mode | pMCMC |

| Random effect | ||||

| Species | 3,604 | 27.3 (0.0006–79.3) | 8.1 | — |

| Individual identification | 3,811 | 22.8 (6.3–46.6) | 15 | — |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept | 3,906 | −57.2 (−97.3 to −21.3) | −54.6 | 0.0004 |

| Brain volume* | 4,211* | 16.2 (3.6–30.5)* | 15.1* | 0.007* |

| Body mass* | 4,567* | −9.5 (−18.6 to −1.6)* | −8.9* | 0.011* |

| Latency to approach | 4,950 | −0.1 (−0.5–0.4) | −0.1 | 0.7 |

| Work time* | 4,950* | 0.6 (0.2–1.1)* | 0.6* | 0.009* |

| Behavioral diversity | 4,950 | 1.1 (−3.7–6.3) | 0.7 | 0.64 |

| Dexterity | 4,671 | 3 (−0.5–7.4) | 2.8 | 0.11 |

| Group size | 4,950 | 0.01 (−0.4–0.4) | 0.03 | 0.92 |

pMCMC is the Bayesian P value. Sample sizes are 398 trials on 112 individuals from 23 different species.

Statistically significant.

Table S4.

Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed effects models to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 18 mammalian carnivore species when at least four individuals were tested in all species

| Fixed or random effect | Effective sample size | Posterior mean (95% CI) | Posterior mode | pMCMC |

| Random effect | ||||

| Species | 2,634 | 34.3 (0.0006–102.6) | 7.6 | — |

| Individual identification | 2,647 | 21.2 (4.9–44.7) | 13.2 | — |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept | 2,456 | −59.7 (−106 to −16.3) | −53.6 | 0.0012 |

| Brain volume* | 2,649* | 16.6 (1.8–32.6)* | 14.6* | 0.012* |

| Body mass* | 2,707* | −9.7 (−20.1 to −1.3)* | −9.3* | 0.018* |

| Latency to approach | 3,284 | 0.07 (−0.4–0.6) | 0.1 | 0.81 |

| Work time* | 3,284* | 0.63 (0.1–1.1)* | 0.6* | 0.01* |

| Behavioral diversity | 3,284 | 1.47 (−3.6–6.5) | 0.7 | 0.55 |

| Dexterity | 3,284 | 2.85 (−0.9–6.9) | 3.1 | 0.13 |

| Group size | 3,284 | 0.08 (−0.4–0.5) | 0.1 | 0.76 |

pMCMC is the Bayesian P value. Sample sizes are 348 trials on 97 individuals from 18 different species.

Statistically significant.

Table S5.

Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed effects models to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 39 mammalian carnivore species when at least 3 trials were performed in all individuals (total number of trials per individual ranged from 3 to 10)

| Fixed or random effect | Effective sample size | Posterior mean (95% CI) | Posterior mode | pMCMC |

| Random effect | ||||

| Species | 4,518 | 15 (0.001–41.8) | 4.9 | — |

| Individual identification | 3,732 | 20.3 (7-38.8) | 16.04 | — |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept | 4,153 | −35.1 (−58.1 to −12.7) | −30.9 | 0.002 |

| Brain volume* | 4,702* | 8.05 (0.79–16.02)* | 8.3* | 0.03* |

| Body mass | 4,803 | −4.3 (−9.23–0.01) | −3.73 | 0.06 |

| Latency to approach | 5,431 | −0.11 (−0.54–0.3) | −0.17 | 0.61 |

| Work time | 5,200 | 0.33 (−0.04–0.74) | 0.29 | 0.08 |

| Behavioral diversity | 5,200 | 2.06 (−1.7–6.3) | 1.53 | 0.3 |

| Dexterity | 4,716 | 2.4 (−0.61–5.5) | 1.85 | 0.11 |

| Group size | 4,912 | −0.08 (−0.39–0.21) | −0.02 | 0.59 |

pMCMC is the Bayesian P value. Sample sizes are 483 trials on 131 individuals from 39 different species.

Statistically significant.

Table S6.

Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed effects models to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 39 mammalian carnivore species when we restricted our analysis to examining only the first three trials for each individual that was tested at least three times

| Fixed or random effect | Effective sample size | Posterior mean (95% CI) | Posterior mode | pMCMC |

| Random effect | ||||

| Species | 2,633 | 19.6 (0.0002–56.3) | 0.1 | — |

| Individual identification | 2,648 | 18.6 (4.4–37.9) | 13.2 | — |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept | 3,012 | −35.6 (−62.2 to −11.9) | −30.9 | 0.002 |

| Brain volume | 3,585 | 7.3 (−0.03–16.1) | 7.7 | 0.052 |

| Body mass | 3,522 | −3.5 (−8.1–1.8) | −3.6 | 0.13 |

| Latency to approach | 3,284 | −0.19 (−0.7–0.3) | −0.2 | 0.49 |

| Work time | 3,284 | 0.25 (−0.3–0.8) | 0.2 | 0.35 |

| Behavioral diversity | 3,284 | 2.8 (−1.5–7.1) | 3.1 | 0.18 |

| Dexterity | 3,284 | 2.7 (−0.7–5.9) | 2.1 | 0.08 |

| Group size | 3,123 | −0.06 (−0.4–0.2) | −0.04 | 0.7 |

pMCMC is the Bayesian P value. Sample sizes are 388 trials on 131 individuals from 39 different species.

Individuals from species with large average group sizes, such as banded mongoose (average group size = 23.7 individuals), were no more successful at opening the puzzle box (pMCMC = 0.79) (Table 2) than individuals from solitary species, such as black bears (group size = 1) or wolverines (group size = 1). To further test whether social complexity affected carnivores’ ability to open the puzzle box, we also compared success at opening the puzzle box between solitary species (group size = 1) and social species (group size > 1) where group size was a binary predictor. This comparison indicated that social species were no better at opening the puzzle box than solitary species (pMCMC = 0.99) (Table S7).

Table S7.

Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed effects models to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 39 mammalian carnivore species

| Fixed or random effect | Effective sample size | Posterior mean (95% CI) | Posterior mode | pMCMC |

| Random effect | ||||

| Species | 4,529 | 16.4 (0.0002–40) | 4.9 | — |

| Individual identification | 3,398 | 21.1 (7.6–40.5) | 16 | — |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept | 5,200 | −1,158 (−110,700–110,400) | −3,215 | 0.99 |

| Brain volume* | 4,876* | 8.1 (0.47–10.6)* | 7.02* | 0.03* |

| Body mass | 5,200 | −4.4 (−8.9–0.62) | −3.6 | 0.06 |

| Latency to approach | 5,200 | −0.13 (−0.57–0.28) | −0.15 | 0.56 |

| Work time | 4,583 | 0.33 (−0.05–0.72) | 0.35 | 0.09 |

| Behavioral diversity | 5,200 | 1.6 (−2.5–5.8) | 1.94 | 0.41 |

| Dexterity | 4,302 | 2.8 (−0.35–6) | 2.3 | 0.064 |

| Social species | 5,200 | 1,122 (−110,400–110,700) | 3,168 | 0.99 |

In this model, group size is a binary variable, where species are either solitary (group size of 1) or social (group size >1). Reference value in the intercept is social species. pMCMC is the Bayesian P value. Sample sizes are 495 trials on 140 individuals from 39 different species.

Statistically significant.

Surprisingly, individuals from species with larger body sizes were less successful than smaller-bodied species at opening the puzzle box (pMCMC = 0.036) (Table 2). Individuals that were more dexterous (pMCMC = 0.08) (Table 2) and those that spent more time attempting to open the puzzle box (pMCMC = 0.08) (Table 2) tended to be more successful, although neither of these were statistically significant. Individuals that more quickly approached the puzzle box (pMCMC = 0.57) (Table 2) or those that used a greater diversity of behaviors when interacting with the puzzle box (pMCMC = 0.39) (Table 2) were no more successful than others at opening the box. In nine of the puzzle box trials, individuals opened the box door but did not retrieve the food reward, which might reflect underlying differences in motivation. We included these trials in our main analyses (Table 2), but also, we ran our analyses without these nine trials and obtained the same qualitative results (Table S8).

Table S8.

In nine of the puzzle box trials, individuals opened the door to retrieve the reward but did not eat the food reward

| Fixed or random effect | Effective sample size | Posterior mean (95% CI) | Posterior mode | pMCMC |

| Random effect | ||||

| Species | 2,426 | 14.4 (0.0007–42.9) | 3.8 | — |

| Individual identification | 2,235 | 21.1 (6.4–39.1) | 16.1 | — |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept | 2,652 | −36.4 (−60.8 to −15.6) | −38.5 | 0.0008 |

| Brain volume* | 2,734* | 8.5 (1.5–16.2)* | 7.6* | 0.011* |

| Body mass* | 2,795* | −4.6 (−9.4 to −0.4)* | −4.1* | 0.035* |

| Latency to approach | 2,617 | −0.13 (−0.53–0.3) | −0.06 | 0.55 |

| Work time | 2,597 | 0.33 (−0.05–0.71) | 0.3 | 0.08 |

| Behavioral diversity | 2,617 | 1.7 (−2.2–5.8) | 1.9 | 0.38 |

| Dexterity | 2,617 | 2.7 (−0.4–5.9) | 1.6 | 0.07 |

| Group size | 2,617 | −0.04 (−0.34–0.25) | 1.3 | 0.8 |

The behavior of these nine animals may suggest differences among individuals in their motivation to open the puzzle box. We performed the same statistical model shown in Table 2 but excluded these nine trials. Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed effects models to investigate the predictors of success in opening the puzzle box in 39 mammalian carnivore species are shown. pMCMC is the Bayesian P value. Sample sizes are 486 trials on 140 individuals from 39 different species.

Statistically significant.

In our brain region analyses, there was no obvious top model that best explained success at opening the puzzle box (Table 3). Models containing relative anterior cerebrum volume (anterior to the cruciate sulcus; ΔDIC = 0) and posterior cerebrum volume (posterior to the cruciate sulcus; ΔDIC = 0) were the two models with the lowest DIC values (Table 3). However, models containing hindbrain volume (which includes both cerebellum and brainstem volumes; ΔDIC = 0.2) or total cerebrum volume (ΔDIC = 0.3) were not considerably worse. Notably, models containing body mass and total brain volume in addition to the volume of one of four specific brain regions all had lower DIC values than a model containing only body mass and total brain volume (ΔDIC ranged from 1.9 to 2.2) (Table 3). This result suggests that the addition of the volume of a brain region to the model improved its ability to predict performance in the puzzle box trials over a model containing only total brain volume (Table 3). In none of the models using the reduced dataset were the relative sizes of any specific brain region associated with success in opening the puzzle box (Table S9).

Table 3.

Model comparisons using DIC model selection to investigate whether the volumes of specific brain regions better predicted success in opening the puzzle box than total brain volume in 17 mammalian carnivore species

| Model name | Fixed effects | λ-Posterior mode | λ-Mean (95% CI) | DIC | ΔDIC |

| Anterior cerebrum | AC + BM + BV | 0.006 | 0.42 (0.0003–0.99) | 88.4 | 0 |

| Posterior cerebrum | PC + BM + BV | 0.004 | 0.37 (0.0002–0.98) | 88.4 | 0 |

| Brainstem/cerebellum | BS/CL + BM + BV | 0.006 | 0.42 (0.004–0.99) | 88.6 | 0.2 |

| Cerebrum | C + BM + BV | 0.006 | 0.41 (0.0003–0.99) | 88.7 | 0.3 |

| Brain | BV + BM | 0.005 | 0.36 (0.0002–0.98) | 90.6 | 2.2 |

Model terms are volume of anterior cerebrum (AC), body mass (BM), volume of brainstem and cerebellum (BS/CL), volume of total brain (BV), volume of total cerebrum (C), and volume of posterior cerebrum (PC). 95% CI, 95% credible interval.

Table S9.

Results from Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed effects models to investigate whether specific brain region volumes predicted success in opening the puzzle box in 17 mammalian carnivore species

| Brain region and fixed/random effects | Effective sample size | Posterior mean | Posterior mode | 95% CI | pMCMC |

| Anterior cerebrum | |||||

| Species | 5,381 | 18.7 | −0.21 | 0.0002–80.3 | — |

| Individual identification | 2,714 | 107.8 | 44.9 | 8.6–308.6 | — |

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Intercept | 4,652 | −136.3 | −93.3 | −411.7–73.1 | 0.17 |

| Brain volume | 4,939 | 10.9 | 5.4 | −12.6–39.5 | 0.32 |

| Body mass | 4,500 | −8.7 | −6.3 | −25.1–3.2 | 0.13 |

| Anterior cerebrum volume | 5,130 | 3.1 | 1.8 | −3.9–11.4 | 0.31 |

| Posterior cerebrum | |||||

| Species | 5,650 | 12.1 | −0.12 | 0.0002–47.7 | — |

| Individual identification | 3,152 | 101.3 | 42.1 | 9.4–280.3 | — |

| Intercept | 5,015 | −147.3 | −83.9 | −429.5–56.2 | 0.12 |

| Brain volume* | 4,587* | 38.1* | 31.2* | −5.6–89.4* | 0.04* |

| Body mass | 5,146 | −8.1 | −4.2 | −24.3–3.5 | 0.14 |

| Posterior cerebrum volume | 4,780 | −24.7 | −14.5 | −68.3–10.6 | 0.12 |

| Total cerebrum | |||||

| Species | 5,571 | 18.3 | −0.19 | 0.0002–78.5 | — |

| Individual identification | 3,084 | 105 | 46 | 12.9–294 | — |

| Intercept | 4,252 | −155.4 | −143.3 | −436.6–73.3 | 0.13 |

| Brain volume | 5,650 | 22.3 | 16.3 | −137.2–184.8 | 0.76 |

| Body mass | 4,222 | −9.2 | −6.8 | −24.6–3.9 | 0.12 |

| Total cerebrum volume | 5,650 | −7.1 | 5.9 | −164.2–145.2 | 0.92 |

| Brainstem and cerebellum | |||||

| Species | 4,616 | 27.1 | −0.24 | 0.0002–110.2 | — |

| Individual identification | 2,760 | 109 | 52.8 | 11.6–304.7 | — |

| Intercept | 3,564 | −158.8 | −82.5 | −456.2–64.1 | 0.11 |

| Brain volume | 5,008 | 17.5 | 10.9 | −23.5–61.9 | 0.33 |

| Body mass | 3,863 | −9.1 | −6.9 | −26.4–4.4 | 0.13 |

| Brainstem and cerebellum volume | 5,986 | −2.3 | 0.3 | −40.7–31.9 | 0.92 |

| Brain volume | |||||

| Species | 4,847 | 9 | −0.10 | 0.0002–41.5 | — |

| Individual identification | 4,149 | 80.2 | 32.3 | 8.7–205.2 | — |

| Intercept | 4,644 | −137.3 | −79.3 | −377.6–31.04 | 0.09 |

| Body mass | 4,669 | −8.2 | −6.6 | −21.2–2.2 | 0.09 |

| Brain volume | 4,911 | 13.6 | 9.1 | −4.1–37.5 | 0.11 |

pMCMC is the Bayesian P value.

Statistically significant.

Discussion

The connection between brain size and cognitive abilities has been called into question by both a study pointing out the impressive cognitive abilities of small-brained species, such as bees and ants (7), and another study doubting that overall brain size is a valid proxy for cognitive ability (9). In the former case, Chittka and Niven (7) argue that larger brains are partially a consequence of the physical need for larger neurons in larger animals and partially caused by increased replication of neuronal circuits, which confers many advantages for larger-brained species, such as enhanced perceptual abilities and increased memory storage. Chittka and Niven (7) conclude that neither of these properties of larger brains necessarily enhance cognitive abilities. Interestingly, our results actually show that carnivore species with a larger average body mass performed worse than smaller-bodied species on the task that we presented to them. Thus, it truly does seem that a larger brain size relative to body size is an important determinant of performance on this task, and it is not the case that larger animals are more successful simply because their brains are larger than those of smaller species.

Regarding whether overall brain size is a valid proxy for cognitive abilities, the use of whole-brain size as a predictor of cognitive complexity in comparative studies is questioned, because the brain has different functional areas, some of which are devoted to particular activities, such as motor control or sensory processing. Given this high degree of modularity in the brain, Healy and Rowe (8, 9) argue that overall brain size is unlikely to be a useful measure when examining how evolution has shaped the brains of different species to perform complex behaviors. Although the brain has functional modules, such as the hippocampus or the olfactory bulbs, which may be under specific selection pressures (31), these modules may also exhibit coordinated changes in size because of constraints on ways in which the brain can develop (32). In addition to functionally specialized modules, the brain also contains broad areas, such as the mammalian neocortex, that control multiple processes. Thus, there are reasons to believe that overall brain size may be an informative proxy for cognitive abilities, despite the modular nature of the brain.

Here we examined relationships between relative brain size, size of specific brain regions, and problem-solving success. Although none of the regional brain volumes that we examined significantly predicted success on this task (Table S9), the addition of the volume of these brain regions improved the ability of our models to explain performance in the puzzle box task over a model containing only total brain volume (Table 3). We emphasize, however, that only 17 species were included in that analysis. Nevertheless, relative brain size was a significant predictor of problem-solving success across species, and this result was robust in all of our analyses. Thus, our data provide important support for the idea that relative brain size can be useful in examining evolutionary relationships between neuroanatomical and cognitive traits and corroborate results from artificial selection experiments showing that larger brain size is associated with enhanced problem solving (5). It will be important in future work to use more detailed noninvasive brain imaging methods rather than endocasts to evaluate whether hypothetically important brain areas, such as prefrontal and cingulate cortexes, contribute to the relationship between brain size and performance during problem solving.

Assessment of the ecological and neuroanatomical predictors of problem-solving ability has some important implications for hypotheses proposed to explain the adaptive value of large brains and sophisticated cognition. One such hypothesis that has garnered much support in primate studies is “the social brain hypothesis” (33, 34), which proposes that larger brains evolved to deal with challenges in the social domain. This hypothesis posits that selection favored those individuals best able to anticipate, respond to, and perhaps even manipulate the actions of conspecific group members. However, a major shortcoming of the social brain hypothesis (35, 36) is its apparent inability to explain the common observation that species with high sociocognitive abilities also excel in general intelligence (37, 38). There is, in fact, a long-standing debate as to whether animal behavior is mediated by cognitive specializations that have evolved to fulfill specific ecological functions or instead, domain-general mechanisms (38, 39). If selection for social agility has led to the evolution of domain-general cognitive abilities, then species living in social groups should solve technical problems better than solitary species. However, we found that carnivore species living in social groups performed no better on our novel technical problem than solitary species. Thus, whereas social complexity may select for enhanced ability to solve problems in the social domain (40), at least in carnivores, greater social complexity is not associated with enhanced ability to solve a novel technical problem.

Our results are similar to those obtained in the work by MacLean et al. (12), which examined relationships among brain size, social complexity, and self-control in 23 species of primates. In both that study and our own study, species with the largest brains showed the best performance in problem-solving tasks. However, in neither primates nor carnivores did social complexity predict problem-solving success. This finding is also consistent with results obtained in the work by Gittleman (41), with analysis of 153 carnivore species that revealed no difference in brain size relative to body size between social and solitary species. Nevertheless, in this study, we were only able to present carnivores with a single problem-solving task, and we were only able to test one to nine individuals per species. Ideally, future studies will present a large array of carnivores with additional cognitive challenges and will test more individuals per species.

A second hypothesis forwarded to explain the evolution of larger and more complex brains, the cognitive buffer hypothesis (42, 43), posits that large brains evolved to allow animals to cope with socioecological challenges and thus, reduce mortality in changing environments. Previous work has shown convincingly that diet is a significant predictor of brain size in carnivores (27), as it is in primates (12), and this study shows that carnivore species with larger brains are more likely to solve a novel technical problem. However, an explicit test of the cognitive buffer hypothesis has not yet been attempted with mammalian carnivores.

Overall, our finding that enhanced problem solving is related to disproportionally large brain size for a given body mass is important for several reasons. First, although there is correlational evidence for an association between absolute or relative brain size and problem-solving abilities, experimental evidence is extremely rare. The lack of experimental evidence has led to criticisms of the use of brain size as a proxy for problem-solving abilities (8, 9, 44). We offer experimental evidence that brain size is, indeed, a useful predictor of performance, at least in the single problem-solving task that we posed to our carnivore subjects. Although only brain size relative to body mass was a significant predictor of success with our puzzle box, species with larger absolute brain volumes also tended to be better than others at opening the puzzle box (Figs. 2 and 3 and Table S2). Second, the vast majority of work on this topic has focused on primates, fish, and birds (5, 10, 11, 13–16). Our results offer new evidence for the relationship between brain size and problem-solving abilities in mammalian carnivores. The previous lack of support for this relationship across a diverse set of taxa has limited both its validity and its generality. Thus, the findings presented here represent an important step forward in our understanding of why some animals have evolved large brains for their body size.

Materials and Methods

From 2007 to 2009, we presented puzzle boxes to myriad carnivores housed in nine North American zoos (Fig. 1A and Dataset S1). Because we were testing animals that ranged in size from roughly 2 to 300 kg, we used two steel mesh puzzle boxes; the larger box was 63.5 × 33 × 33 cm, and the smaller box was one-half that size. The smaller box was presented to species with an average body mass of <22 kg, such as river otters, kinkajous, sand cats, and other small-bodied carnivores (Dataset S1). The larger box was presented to species with an average body mass >22 kg, including snow leopards, wolves, bears, and other large-bodied species (Dataset S1). For cheetahs (species average body mass = 50 kg) and wild dogs (species average body mass = 22.05 kg), both large and small boxes were used with some subjects, but their performance did not vary with box size (additional details are given in SI Text).

We videotaped all trials and extracted performance measures from videotapes using methods described elsewhere (24, 28, 45) (Movie S1). Extracted behaviors included the latency to approach the puzzle box, the total time spent trying to open the box, the number of different behaviors used in attempting to open the box, and a measure of manual dexterity (all described in SI Text). We then brought together data on success and performance measures during zoo trials with previously published data on total brain size and body mass (46).

We used Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed-effects models based on a Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm implemented in the R package MCMCglmm (47–49) to identify the variables predicting success or failure in solving this puzzle. These models allowed us to assess the effects of predictor variables on carnivores’ success at opening the puzzle box after controlling for shared phylogenetic history.

For our analyses of how brain volume affected the ability of carnivores to open the puzzle box, we constructed 12 different models containing different combinations of the morphological, behavioral, and social characteristics of tested species or individuals (Table 1). In all models except that shown in Table S2, we included species’ average body mass as a covariate so that we could assess the effects of brain volume on puzzle box performance relative to body mass (50, 51). We used DIC (51) to examine the relative degree of fit of the different models. DIC is analogous to Akaike’s information criterion (52), and lower values for DIC suggest a better fit. We present DIC values for all models (Table 1) but only present results from the model with the lowest DIC (Table 2) (53).

In separate analyses, we performed five different Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed-effects models to determine whether the volume of any specific brain region better predicted success in opening the puzzle box than overall endocranial volume (Table 3). These models also included species’ average body mass and total brain volume as covariates (27). Computed tomography data were available documenting both total endocranial volume and the volumes of specific brain regions from 17 different carnivore species in six families (Dataset S1). Overall endocranial volume was subdivided into (i) cerebrum anterior to the cruciate sulcus, (ii) cerebrum posterior to the cruciate sulcus, (iii) total cerebrum, and (iv) hindbrain, which includes both cerebellum and brainstem. The cerebrum anterior to the cruciate sulcus is comprised mainly of frontal cortex. Additional methodological details on the estimation of these brain region volumes can be found elsewhere (54–56) (SI Text).

Our response variable was binary (did or did not open puzzle box); therefore, we used a categorical error structure in MCMCglmm, and we fixed the prior for the residual variance to one (V = 1; fix = 1). We included random effects for species and individual identity in these models. We used weakly informative inverse γ-priors with a low degree of belief (V = 1; μ = 0.002) for the random effect variance. All models were run for appropriate numbers of iterations, burn-ins, and thinning intervals to generate a minimum effective sample size of >2,000 for all parameters in all of the different models. We provide the mean, mode, and 95% credible interval from the posterior distribution of each parameter. We considered parameters to be statistically significant when the 95% credible intervals did not overlap zero and pMCMC was <0.05 (47). Detailed statistical methods are in SI Text.

Appropriate ethical approval was obtained for this work. This work was approved by Michigan State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) Approval 03/08-037-00 and also, the IACUCs at all nine zoos (St. Louis Zoo, Bergen County Zoo, Binder Park Zoo, Potter Park Zoo, Columbus Zoo, The Living Desert, Wild Canid Survival and Research Center, Turtle Back Zoo, and Denver Zoo) where testing was done.

SI Text

Administration of Puzzle Box Trials in Zoos.

We ran puzzle box trials with carnivores maintained at nine North American zoos: St. Louis Zoo, St. Louis; Bergen County Zoo, Paramus, NJ; Binder Park Zoo, Battle Creek, MI; Potter Park Zoo, Lansing, MI; Columbus Zoo, Columbus, OH; The Living Desert, Palm Desert, CA; Wild Canid Survival and Research Center, Eureka, MO; Turtle Back Zoo, West Orange, NJ; and Denver Zoo, Denver.

Both large and small puzzle boxes allowed subjects to see and smell the bait inside, and all worked in exactly the same way: the animal had to slide a simple bolt latch sideways to have the hinged door swing open so that the food inside could be accessed, or move the box around until it was oriented such that the bolt would fall open as described previously (24, 28) (Movie S1). Baits were chosen based on what zoo keepers told us was the favorite food of each individual tested. Baits ranged from bamboo to dead baby goats, but in all cases, the bait could not exit the box unless the door was opened.

We tested animals that ranged in size from roughly 2 to 300 kg, and therefore, we used two steel mesh puzzle boxes of different sizes. The larger box was 63.5 × 33 × 33 cm, and the smaller box was one-half that size. The smaller box was presented to species with an average body mass of <22 kg, such as river otters, kinkajous, sand cats, and other small-bodied carnivores (Dataset S1). The larger box was presented to species with an average body mass >22 kg, including snow leopards, wolves, bears, and other large-bodied species (Dataset S1). However, for cheetahs (species average body mass = 50 kg) and wild dogs (species average body mass = 22.05 kg), both the large and small boxes were used with some subjects (cheetahs: three individuals tested with the small box and six individuals tested with the large box; wild dogs: three individuals tested with the small box and two individuals tested with the large box). Boxes presented to these two species varied in size because of specific requests by animal keepers at three zoos for a smaller box size after the larger box had already been used for these species at other locations. This variation in box size used did not affect our results given that no individual cheetah opened any puzzle box, regardless of its size. Moreover, in wild dogs, individuals were roughly as likely to open the small (22% of trials: two of nine total trials) as the large box (16.7%: one of six total trials). Finally, we also examined whether a species’ body mass influenced its ability to open the box within each of two box sizes in separate analyses from those described above. Using the same model shown in Table 2 but only for individuals given the large [effect of body mass: 95% credible interval (95% CI) = −4.93–14.32; pMCMC = 0.52] or small (effect of body mass: 95% CI = −8.55–4.4; pMCMC = 0.51) box, we found no effect of body mass on the ability to open the puzzle box.

Each subject was tested alone in its home enclosure, all subjects were fasted for 24 h before testing, and all trials were videotaped in their entirety. Each subject was briefly moved to an adjacent enclosure while the baited box was placed in the animal’s home enclosure, the latch handle was set to protrude at a 90° angle from the door, and a tripod-mounted video camera was aimed to center on the box from just outside the home enclosure. The box was always oriented such that its door was at right angles to the focal plane of the camera. The subject was then moved back into its home enclosure for testing. All zoo testing was conducted by G.S. The experimenter either was hidden completely from the subject or filmed the trial from among the zoo patrons visiting the exhibit. Trials lasted 30 min or until the animal obtained the bait from the box (mean amount of time attempting to open the box = 329.2 s; minimum = 0 s; maximum = 1,683 s). The box was scrubbed with disinfectant (whichever one was routinely used at that facility) and rinsed between trials.

For most subjects, each trial started when the animal entered the test enclosure, because the puzzle box was immediately within its field of view. However, in a few cases, the enclosure was large and full of foliage, such that the animal could enter the test enclosure but remain unaware of the presence of the puzzle box. For these individuals, we started trials at the first instant when the subject had a direct line of sight to the puzzle box and its orientation behavior indicated that it had detected the box. Thus, in all cases, a trial started when an individual could see the puzzle box, and the period of exposure to the puzzle box was 30 min for all subjects. Given that no trial began until the subject was clearly aware of the presence of the puzzle box, any difference in trial start time caused by the size of the enclosure or the density of foliage is likely to be negligible in a 30-min time window.

We conducted 495 trials in total, because we tested one to nine individuals per each of 39 species (mean = 4.9 individuals; median = 5) (Table S1). At least three different individuals were tested in 23 of 39 species, but in 12 species, there were only two individuals tested, and in 4 species, only one individual was tested. The average number of trials conducted per individual (mean = 4.2 trials; median = 3; range = 1–10) varied among species (Table S1). Each individual within each species was tested with the puzzle box approximately three times, but if the subject did not succeed at opening the puzzle box by its third trial, we conducted no additional trials. Some individuals were tested in more than three trials, because when permitted by zoo staff to do so, we attempted to calculate learning curves for a different study.

Our results were not sensitive to variation in either the total number of individuals tested per species or the average number of trials conducted per individual. Specifically, we obtained the same results if we limit our analyses only to species in which at least three (Table S3) or four individuals (Table S4) were tested or only individuals to which we administered at least 3 separate trials (total number of trials per individual was 3–10) (Table S5) or when we restricted our analysis to examining only the first 3 trials for each individual (Table S6). These additional analyses indicated that our main conclusion was robust to different methods of analysis and different subsets of the data, and thus that brain size relative to body mass influenced the likelihood that carnivore species would open the puzzle box but that sociality and other variables did not.

As in all comparative studies that examine behavioral responses across a broad range of species, care must be taken to minimize variation among species because of the different ecologies of those species. In recent years, there also has been a lively debate over the possibility that cognitive tests often fail to account for variation in performance among subjects because of differences in motivation, body morphology, cue salience, or prior experiences (8, 44, 57, 58). In this study, we attempted to deal with these issues by restricting our experiments to species from a single order and controlling for factors, such as manual dexterity and neophobia (measured as the latency to approach the puzzle box). To bring each individual up to a high level of motivation before testing, we presented each animal with its favorite food as a reward for opening the puzzle box and fasted each animal for 24 h before trials. Thus, red pandas seemed just as highly motivated to solve the puzzle for a reward of bamboo as Amur tigers for a reward of raw meat. Additionally, we purposefully designed an artificial task that individuals would not likely have previously experienced (59, 60). This task did not require individuals to associate rewards with particular colors or shapes, which may introduce bias into results. Instead, the reward in this task was easily discernable from both visual and olfactory cues. In nine of the puzzle box trials, individuals opened the box door but did not retrieve the food reward, which might reflect underlying differences in motivation. We included these trials in our main analyses (Table 2) but also, ran our analyses without these nine trials and found the same qualitative results (Table S8). Interestingly, we found that species with a larger body masses were less successful than smaller species (results reported in the text). This finding may be an artifact of fasting all animals for the same 24-h time period before testing. It is possible that small species may be hungrier after a 24-h fasting period than larger species, and thus, motivation may be higher in smaller-bodied species. However, we think this possibility is unlikely given that the behavior of the animals did not indicate a lack of motivation to solve the problem. Latency to approach the puzzle box did not influence success in solving the problem (Table 2), and only one tested individual appeared uninterested in the food reward.

One factor that may have influenced performance on this task for which we could not fully account was the enrichment history of each captive subject. We tested carnivores housed in nine different zoos, and it is possible that individual animals experienced varying levels of enrichment and had different experiences with manmade objects before our tests. Although it would be ideal to test only individuals with identical prior experiences, it is difficult to imagine how large comparative tests where individuals from a range of species are presented with cognitive challenges could ever fully account for variation in enrichment histories. Even studies like that by MacLean et al. (12) compared results from species that were housed in many different research facilities around the world. It is quite likely that individuals in these facilities experienced varying exposures to manmade objects and even had different histories of participating in experiments where they were exposed to novel situations and cognitive challenges. One way to try and account for some of this variation is to include zoo identification as a random effect in our statistical models. This method assumes that individuals that are housed in the same zoo have similar enrichment experiences compared with individuals housed in different zoos. We did this and found that inclusion of zoo as a random effect had no effect on our main conclusion that carnivore species with larger brains for their body mass perform better in the puzzle box tests. Specifically, when zoo was included as a random effect in the top model shown in Table 1, where DIC was 283.2, the DIC value for this same model but now including zoo increased slightly to 283.5, suggesting that the addition of zoo as a random effect did not improve the overall fit of our top model. Furthermore, the effect of total brain volume on puzzle box performance in the top model shown in Table 2 but now including zoo as a random effect was similar in magnitude and direction (95% CI = 1.71–16.29; pMCMC = 0.016) as the top model shown in Table 1 without zoo as a random effect (Table 2). However, because not all species were tested in every zoo, we did not include zoo as a random effect in the models presented in our results, because including zoo leads to colinearity among the different random effects. Thus, although we have no reason to believe that the enrichment histories of the animals included in this study influenced our results, it would be ideal for future studies to try to minimize variation in enrichment histories as much as possible.

Extraction of Behavioral Data.

S.B.-A. performed all data extraction from videotapes of zoo trials, and Adam Overstreet assisted with extracting measures of manual dexterity. We calculated interobserver reliability for our measure of dexterity. We had two observers extract dexterity measures for 10% of the trials, and our measure of interobserver reliability was very high (R = 0.94; Spearman rank correlation). Therefore, we are confident that our dexterity measures are highly reliable. We extracted performance measures from video footage as described earlier (24, 28). Briefly, we recorded the time taken to approach the puzzle box after the subject first detected the box (latency to approach box) as a measure of motivation to obtain the food reward. We scored work time as the number of seconds after trial onset during which the subject had its head down and was oriented toward and focused on the puzzle box before either opening the box or the trial ended. To score behavioral diversity, we looked for 13 behaviors of which all subjects were physically capable and scored whether an individual exhibited each behavior. Each individual, thus, received a score from 0 to 13. Here, we only scored each subject’s first trial with the puzzle box. The 13 behaviors were rub, foot on box, sniff, lick, dig, bite, pull box with mouth, push box with head, push box with paw, pull box with paw, stand on box, tip box, and flip box. The highest score was 10 [achieved by three individuals: two coatis (Nasua narica) and one bobcat (Lynx rufus)], and the lowest score was 0 [nine individuals: one from each of the following species: bobcat (L. rufus), caracal (Caracal caracal), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), kinkajou (Potos flavus), red panda (Ailurus fulgens), ringtail (Bassariscus astutus), river otter (Lontra canadensis), sand cat (Felis margarita), and serval (Leptailurus serval)]. To score manual dexterity, we adopted methods from the work by Iwaniuk et al. (26) and scored each individual on 20 measures of forelimb movements, which we summed to calculate an overall measure of forelimb dexterity. The movements that we scored included

Body postures,

Limb crosses midline,

Alternate limb use,

Upper forelimb moves in more than one plane,

Upper forelimb rotation,

Lower forelimb rotation,

Grasping,

Picks up items,

Unimanual grasping,

Whole-forepaw grasp,

Digit 2–Digit 3 grasp,

Claw grasp,

Other grasp,

Independent digit movement,

Frequency of manipulation,

Items swapped between forepaws,

Items rotated by forepaw,

Distal digits used in manipulation,

Forepaws pull away from each other, and

Other forepaw movement.

We used no specific measure to quantify anxiety in our subjects during trials, but we did take all possible steps to minimize subjects’ anxiety, such as having the videographer conceal himself from the subject after starting each video recording but before the subject was introduced back into its home enclosure. As can be seen in Movie S1 of our trials, our subjects generally appeared to be keenly interested in the food inside the box and did not exhibit behaviors indicative of anxiety, such as cowering. In future studies, however, it would be beneficial to quantify anxiety and determine, for example, whether individuals that are typically housed in social groups perform worse on cognitive challenges when tested alone than individuals that are typically housed alone.

Group Size as a Measure of Social Complexity.

The use of social group size as a measure of social complexity has been criticized, because animals living in very large groups, such as ungulate herds, need not necessarily cope simultaneously with multiple types of differentiated relationships (61). However, in this study, we used published measures of species’ average group size (27) as a proxy for social complexity, because Swanson et al. (27) found that this was no more or less effective than using the first principal component (PC1) from a principal component analysis of several different measures of social complexity in mammalian carnivores, indicating that group size is just as effective as more comprehensive measures of gregariousness available for mammalian carnivores. Furthermore, group size is a standard measure of social complexity that has been used repeatedly in the social complexity literature (34, 62, 63). For example, in a recent comparative study investigating the evolution of self-control (12), social group size was the predictor variable used to test the social complexity hypothesis. This study by MacLean et al. (12) is similar to our study in that they presented the same cognitive challenges to a number of individuals from a broad array of species and asked whether brain size, group size, or various ecological factors predicted success in these tests. We analyzed our data using group size as a continuous predictor variable (see below), but we also ran a separate analysis, in which we inquired whether social or nonsocial species (group size >1 or 1, respectively) were better able to open the puzzle box (results are shown in Table S7). These results confirmed the conclusion from our other analyses (Table 2) that group size or sociality does not influence performance in the puzzle box trials.

Total and Regional Brain Volumes.

We obtained total brain volume (in milliliters) and adult body mass (in kilograms) data for each tested carnivore species from previously published datasets (46). Virtual endocasts, the digital casts made from the cranial bones comprising the brain case, were created using computed tomography (CT) and the software package MIMICS 11.02 (Materialise, Inc.) (table S7 in ref. 27). We obtained measures of total endocranial volume (in millimeters3); the volumes of the anterior cerebrum, the posterior cerebrum, the total cerebrum (volumes of the posterior cerebrum and the anterior cerebrum), and the cerebellum plus brainstem, and body mass (in kilograms). Cranial and endocranial measures used in our analysis included combined cerebellum and brainstem volume in millimeters3 (cerebellum plus brainstem), cerebrum anterior to the cruciate sulcus in millimeters3 (volume of the anterior cerebrum), and cerebrum posterior to the cruciate sulcus in millimeters3 (volume of the posterior cerebrum). The work by Swanson et al. (27) has additional details about these measurements, and the works by Sakai et al. (54, 55) have details on the CT scanning methods and application of MIMICS software to generate volumetric data for specific brain areas.

Statistical Methods.

We defined a puzzle box trial as successful if the individual opened the box, and therefore, our response variable was binary (an individual did or did not open the puzzle box). Most individuals were tested in the puzzle box trials at least three times (mean = 4.2, median = 3, range = 1–10). Rather than averaging performance among these trials either within an individual or within a species, we used each individual trial as our unit of replication. We used two different datasets in our analysis of relationships between predictor traits and success opening the puzzle box. First, we used a large dataset containing puzzle box performance data from 495 trials on 140 different individuals in 39 species to investigate how total brain volume (from ref. 46), group size, dexterity, work time, and behavioral diversity affected performance in the puzzle box test. Second, we used a smaller dataset containing 209 trials on 65 individuals from 17 tested species to analyze the effects of size of specific brain regions on performance in the puzzle box trials (all data used in this study are in Dataset S1). Data documenting both total endocranial volume (overall brain size) and volumes of specific brain regions were obtained from CT scans from a total of 17 species (data from ref. 27).

To account for the shared evolutionary history among our subject species, we used Bayesian phylogenetic generalized linear mixed-effects models implemented in MCMCglmm (47, 48). Phylogeny was included as the inverse of the variance–covariance matrix, and we also included species as a random effect in these models (48). We obtained our mammalian phylogeny from an updated version of a recent mammalian supertree phylogeny (64) from the work by Fritz et al. (65). We pruned species not in Dataset S1 in R (version 3.2.0) (66) using the package geiger (version 2.0.3) (67). Pagel’s λ is a measure of phylogenetic autocorrelation among the residuals that ranges from zero to one (51, 68). We estimated and report an approximate Bayesian equivalent of Pagel’s λ (phylogenetic heritability) in all of our models as described elsewhere (48, 69).

We investigated how brain volume affected performance in the puzzle box task in a model that included the following fixed effects: brain volume, body mass, latency to approach the box, work time, behavioral diversity, manual dexterity, and average group size. In separate models, we included group size2 but found no nonlinear relationship between group size and performance in the puzzle box task. We, therefore, did not include group size2 in our other models or the results presented in the text or SI Text. We log-transformed (base e) brain volume, body mass, and all behavioral variables before analysis. We included individual identity as a random effect, because we had multiple measures on the same individuals. Although we tested multiple species at each zoo, we did not include a random effect for zoo identity, because we did not measure each species at each zoo. Inclusion of zoo identity as a random effect in preliminary analyses also failed to influence our inferences presented in the text or SI Text (results are presented above).

We used DIC (52) to examine the relative degree of fit of different models that we constructed to contain different combinations of the predictor variables (brain volume, body mass, behavioral variables, and group size) (Table 1). Overall, the model with the lowest DIC was the model containing the brain, body mass, behavioral, and group size predictor variables (Table 1), and therefore, we present the results from these analyses (Table 2).

We used DIC values from five candidate models to determine whether the volume of any specific brain region relative to total brain volume and body mass better predicted success in opening the puzzle box than total brain volume relative to body mass. These models contained (i) total brain volume relative to body mass, (ii) PC volume, (iii) AC volume, (iv) cerebrum volume, or (v) cerebellum plus brainstem volume. All of these models contained fixed effects for total brain volume and body mass (27) as well as random effects for species and individual identity. Because of our small sample sizes in these analyses and to avoid overparameterizing the models, we did not include the fixed effects for latency to approach the box, work time, behavioral diversity, manual dexterity, and average group size. The model with the lowest DIC value was assumed to be the top model.

For the random effects (species and individual identity) in all of our models, we used inverse Wishart priors that specified variance (V) and degree of belief in V (μ). Because our response variable was binary, we used a fixed prior (V = 1; fix = 1). For the random effect variance, we used weakly informative priors with a low degree of belief (V = 1; μ = 0.002), which in this case, are also called inverse γ-priors and are widely used. Models for our first set of analyses on total brain volume (those shown in Table 2 and Tables S2–S8) were run for 8–10 million iterations with a burn-in of 150,000 and a thinning interval of 3,000. Models for our second set of analyses on brain region volume using 17 species were run for 85 million iterations with a burn-in of 250,000 and a thinning interval of 15,000 (Table S9). These different numbers of iterations were used to generate a minimum of an effective sample size of >2,000 in all of the different models (but effective sample sizes were generally much higher than 2,000 as shown in Table 2 and Tables S2–S9).

We confirmed convergence of our posterior distributions using diagnostic tests available in the R package coda (version 0.17–1) (70), including the Geweke convergence diagnostic (71) and the Gelman–Rubin statistic (72). We ran all of our main models three times [although only results from the first Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chain are shown] so that we could calculate the Gelman–Rubin statistic (potential scale reduction) (72–73). All potential scale reduction factors were ≤1.01, which is good evidence that the MCMC chains converged (72, 73). Autocorrelation among the MCMC chains can reduce the effective sample size, but in all of our models, our effective sample sizes were >2,000, indicating that our number of iterations and thinning interval were appropriate to generate sufficient sample sizes. All of our MCMCglmm models used slice sampling.

Inverse Wishart priors, like the ones that we used, are generally weakly informative, except when the posterior density is close to zero (74). In our models, the posterior density estimate for the random effect of species was relatively close to zero (diagnosed visually in trace plots). The use of more informative parameters or parameter-expanded priors may be used as an alternative in such situations (74). We, therefore, also examined how robust our results were to the use of alternative priors for the variance of the random effect for species. Specifically, we ran the same models using more informative priors (e.g., V = 10 and μ = 1; V = 100 and μ = 1, or V = 100 and μ = 2) or parameter-expanded priors (e.g., V = 1; μ = 1; αμ = 0; αV = 625) (75). Using these different priors for the variance of the random effect for species, the models once again provided the inference that species with larger brains for their body mass were better able to open the puzzle box, although the posterior distributions for the parameters changed. Moreover, if we reran the models excluding the random effect of species entirely, we still found the same qualitative results that species with larger brains for their body mass were better able to open the puzzle box. This result suggests that our use of a weak prior (V = 1; μ = 0.002) for the variance for the random effect of species was appropriate and that the results were robust to the use of alternative priors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Glickman for inspiring this work and Adam Overstreet for help with data extraction. We thank Dorothy Cheney, Robert Seyfarth, Jeff Clune, and three anonymous reviewers for many helpful suggestions and discussions. This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) Grants IOS 1121474 (to K.E.H.) and DEB 1353110 (to K.E.H.) and NSF Cooperative Agreement DBI 0939454 supporting the BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action. E.M.S. was supported by NSF Postdoctoral Fellowship 1306627.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1505913113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Roth G, Dicke U. Evolution of the brain and intelligence. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9(5):250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wehner R, Fukushi T, Isler K. On being small: Brain allometry in ants. Brain Behav Evol. 2007;69(3):220–228. doi: 10.1159/000097057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Striedter GF. Principles of Brain Evolution. Sinauer; Sunderland, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiello LC, Wheeler P. The expensive-tissue hypothesis: The brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Curr Anthropol. 1995;36(2):199–221. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotrschal A, et al. Artificial selection on relative brain size in the guppy reveals costs and benefits of evolving a larger brain. Curr Biol. 2013;23(2):168–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isler K, van Schaik CP. The expensive brain: A framework for explaining evolutionary changes in brain size. J Hum Evol. 2009;57(4):392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chittka L, Niven J. Are bigger brains better? Curr Biol. 2009;19(21):R995–R1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healy SD, Rowe C. Costs and benefits of evolving a larger brain: Doubts over the evidence that large brains lead to better cognition. Anim Behav. 2013;86(4):e1–e3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Healy SD, Rowe C. A critique of comparative studies of brain size. Proc Biol Sci. 2007;274(1609):453–464. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madden J. Sex, bowers and brains. Proc Biol Sci. 2001;268(1469):833–838. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garamszegi LZ, Eens M. The evolution of hippocampus volume and brain size in relation to food hoarding in birds. Ecol Lett. 2004;7(12):1216–1224. [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacLean EL, et al. The evolution of self-control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(20):E2140–E2148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323533111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sol D, Duncan RP, Blackburn TM, Cassey P, Lefebvre L. Big brains, enhanced cognition, and response of birds to novel environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(15):5460–5465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408145102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sol D, Timmermans S, Lefebvre L. Behavioural flexibility and invasion success in birds. Anim Behav. 2002;63(3):495–502. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sol D, Lefebvre L, Rodríguez-Teijeiro JD. Brain size, innovative propensity and migratory behaviour in temperate Palaearctic birds. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272(1571):1433–1441. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sol D, Lefebvre L. Behavioural flexibility predicts invasion success in birds introduced to New Zealand. Oikos. 2000;90(3):599–605. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotrschal A, Corral-Lopez A, Amcoff M, Kolm N. A larger brain confers a benefit in a spatial mate search learning task in male guppies. Behav Ecol. 2015;26(2):527–532. doi: 10.1093/beheco/aru227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mech LD. Possible use of foresight, understanding, and planning by wolves hunting muskoxen. Arctic. 2007;60(2):145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey I, Myatt JP, Wilson AM. Group hunting within the Carnivora: Physiological, cognitive and environmental influences on strategy and cooperation. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2013;67(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vonk J, Jett SE, Mosteller KW. Concept formation in American black bears, Ursus americanus. Anim Behav. 2012;84(4):953–964. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gittleman JL. Carnivore group living: Comparative trends. In: Gittleman JL, editor. Carnivore Behaviour, Ecology and Evolution. Cornell Univ Press; Ithaca, NY: 1989. pp. 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stankowich T, Haverkamp PJ, Caro T. Ecological drivers of antipredator defenses in carnivores. Evolution. 2014;68(5):1415–1425. doi: 10.1111/evo.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holekamp KE, Dantzer B, Stricker G, Shaw Yoshida KC, Benson-Amram S. Brains, brawn and sociality: A hyaena’s tale. Anim Behav. 2015;103:237–248. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benson-Amram S, Holekamp KE. Innovative problem solving by wild spotted hyenas. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;279(1744):4087–4095. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornton A, Samson J. Innovative problem solving in wild meerkats. Anim Behav. 2012;83(6):1459–1468. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwaniuk AN, Pellis SM, Whishaw IQ. Brain size is not correlated with forelimb dexterity in fissiped carnivores (Carnivora): A comparative test of the principle of proper mass. Brain Behav Evol. 1999;54(3):167–180. doi: 10.1159/000006621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanson EM, Holekamp KE, Lundrigan BL, Arsznov BM, Sakai ST. Multiple determinants of whole and regional brain volume among terrestrial carnivorans. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benson-Amram S, Weldele ML, Holekamp KE. A comparison of innovative problem-solving abilities between wild and captive spotted hyaenas, Crocuta crocuta. Anim Behav. 2013;85(2):349–356. [Google Scholar]