Significance

Phenylketonuria and milder hyperphenylalaninemias constitute the most common inborn error of amino acid metabolism, usually caused by defective phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH). Although a highly restricted diet prevents intellectual impairment during development, additional therapies are required to combat cognitive dysfunction, executive dysfunction, and psychiatric disorders that arise due to dietary lapses throughout life. New therapies can arise from thorough understanding of the conformational space available to full-length PAH, which has defied crystal structure determination for decades. We present the first X-ray crystal structure of full-length PAH, whose solution relevance is supported by small-angle X-ray scattering. The current structure is an autoinhibited tetramer; the scattering data support the existence of an architecturally distinct tetramer that is stabilized by the allosteric activator phenylalanine.

Keywords: phenylalanine hydroxylase, phenylketonuria, X-ray crystallography, small-angle X-ray scattering, allosteric regulation

Abstract

Improved understanding of the relationship among structure, dynamics, and function for the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) can lead to needed new therapies for phenylketonuria, the most common inborn error of amino acid metabolism. PAH is a multidomain homo-multimeric protein whose conformation and multimerization properties respond to allosteric activation by the substrate phenylalanine (Phe); the allosteric regulation is necessary to maintain Phe below neurotoxic levels. A recently introduced model for allosteric regulation of PAH involves major domain motions and architecturally distinct PAH tetramers [Jaffe EK, Stith L, Lawrence SH, Andrake M, Dunbrack RL, Jr (2013) Arch Biochem Biophys 530(2):73–82]. Herein, we present, to our knowledge, the first X-ray crystal structure for a full-length mammalian (rat) PAH in an autoinhibited conformation. Chromatographic isolation of a monodisperse tetrameric PAH, in the absence of Phe, facilitated determination of the 2.9 Å crystal structure. The structure of full-length PAH supersedes a composite homology model that had been used extensively to rationalize phenylketonuria genotype–phenotype relationships. Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) confirms that this tetramer, which dominates in the absence of Phe, is different from a Phe-stabilized allosterically activated PAH tetramer. The lack of structural detail for activated PAH remains a barrier to complete understanding of phenylketonuria genotype–phenotype relationships. Nevertheless, the use of SAXS and X-ray crystallography together to inspect PAH structure provides, to our knowledge, the first complete view of the enzyme in a tetrameric form that was not possible with prior partial crystal structures, and facilitates interpretation of a wealth of biochemical and structural data that was hitherto impossible to evaluate.

Mammalian phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) (EC 1.14.16.1) is a multidomain homo-multimeric protein whose dysfunction causes the most common inborn error in amino acid metabolism, phenylketonuria (PKU), and milder forms of hyperphenylalaninemia (OMIM 261600) (1). PAH catalyzes the hydroxylation of phenylalanine (Phe) to tyrosine, using nonheme iron and the cosubstrates tetrahydrobiopterin and molecular oxygen (2, 3). A detailed kinetic mechanism has recently been derived from elegant single-turnover studies (4). PAH activity must be carefully regulated, because although Phe is an essential amino acid, high Phe levels are neurotoxic. Thus, Phe allosterically activates PAH by binding to a regulatory domain. Phosphorylation at Ser16 potentiates the effects of Phe, with phosphorylated PAH achieving full activation at lower Phe concentrations than the unphosphorylated protein (5, 6). Allosteric activation by Phe is accompanied by a major conformational change, as evidenced by changes in protein fluorescence and proteolytic susceptibility, and by stabilization of a tetrameric conformer (3).

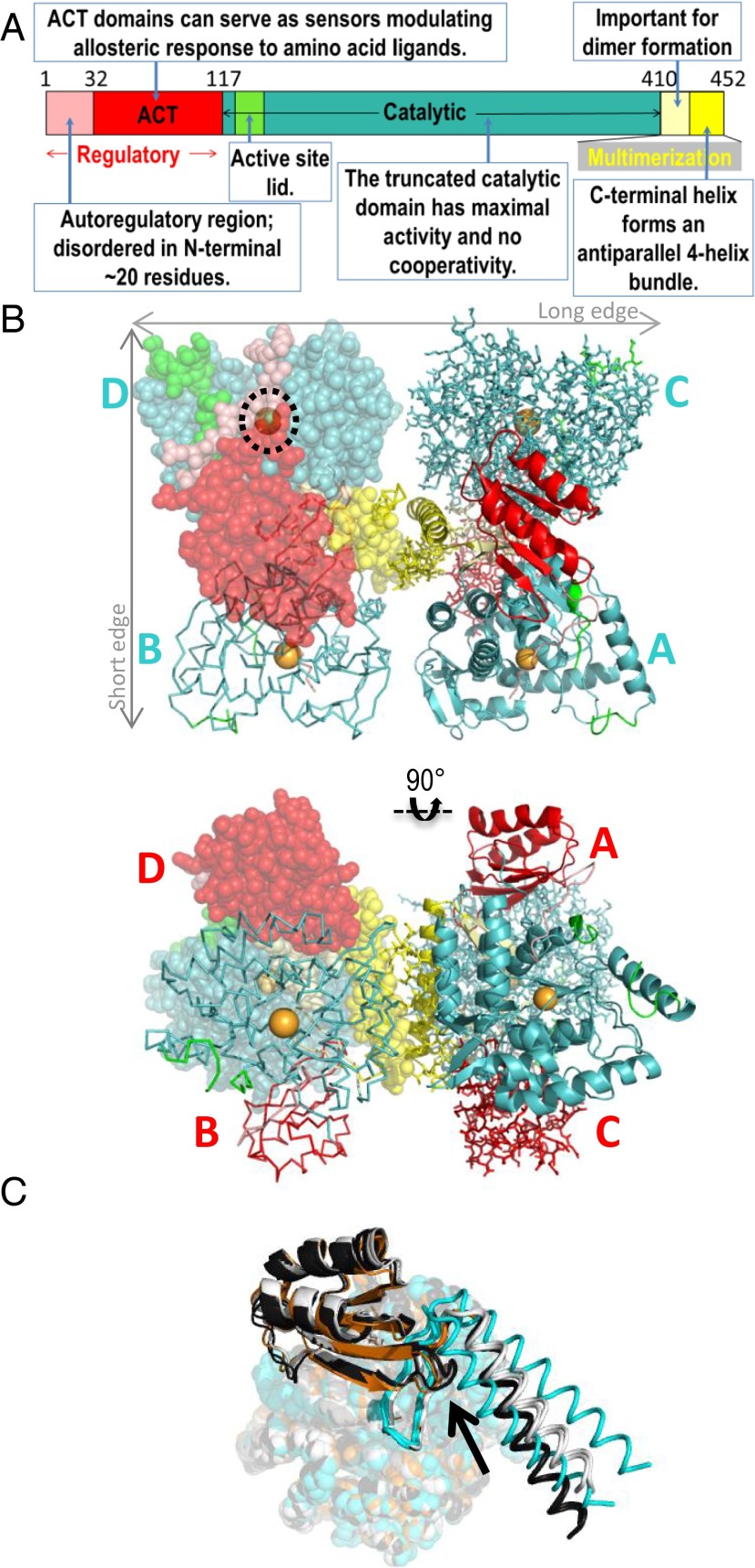

There are >500 disease-associated missense variants of human PAH; the amino acid substitutions are distributed throughout the 452-residue protein and among all its domains (Fig. 1A) (7–9). Of those disease-associated variants that have been studied in vitro (e.g., ref. 10), some confound the allosteric response, and some are interpreted as structurally unstable. We also suggest that the activities of some disease-associated variants may be dysregulated by an altered equilibrium among conformers having different intrinsic levels of activity, arguing by analogy to the enzyme porphobilinogen synthase (PBGS) and its porphyria-associated variants (11). Consistent with this notion, we have recently established that PAH can assemble into architecturally distinct tetrameric conformers (12), and propose that these conformers differ in activity due to differences in active-site access. This idea has important implications for drug discovery, as it implies that small molecules could potentially modulate the conformational equilibrium of PAH, as has already been demonstrated for PBGS (e.g., ref. 13). Deciphering the relationship among PAH structure, dynamics, and function is a necessary first step in testing this hypothesis.

Fig. 1.

The structure of PAH. (A) The annotated domain structure of mammalian PAH. (B) The 2.9 Å PAH crystal structure in orthogonal views, colored as in part A, subunit A is shown in ribbons; subunit B is as a Cα trace; subunit C is in sticks; and subunit D is in transparent spheres. In cyan, the subunits are labeled near the catalytic domain (Top); in red, they are labeled near the regulatory domain (Bottom). The dotted black circle illustrates the autoregulatory domain partially occluding the enzyme active site (iron, in orange sphere). (C) Comparison of the subunit structures of full-length PAH and those of the composite homology model; the subunit overlay aligns residues 144–410. The four subunits of the full-length PAH structure (the diagonal pairs of subunits are illustrated using either black or white) are aligned with the two subunits of 2PAH (cyan) and the one subunit of 1PHZ (orange). The catalytic domain is in spheres, the regulatory domain is in ribbons, and the multimerization domain is as a Cα trace. The arrow denotes where the ACT domain and one helix of 2PAH conflict.

Numerous crystal structures are known for one- and two-domain constructs of mammalian PAH (Table S1). However, until now, no structure has been available for the full-length, three-domain enzyme, possibly because the presence of multiple distinct conformers frustrated efforts to crystallize the full-length protein. Recognition of the existence of alternate tetrameric assemblies and the ability to isolate a single species has now allowed us to generate monodisperse samples of full-length rat PAH suitable for biophysical analysis using X-ray crystallography and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). We report here, to our knowledge, the first crystal structure for full-length PAH, at a resolution of 2.9 Å, which supersedes a composite homology model that has been used since 1999 to help rationalize PKU-related genotype/phenotype relationships (14).

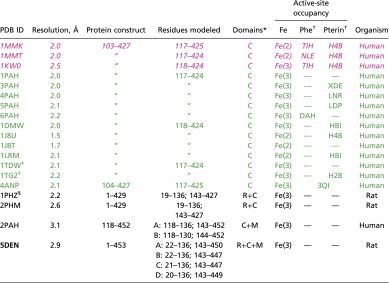

Table S1.

Mammalian PAH structures available in the PDB (August 2015)

|

Entries are colored by configuration of the active-site lid (approximately residues 130–150): “open,” “closed,” and “disordered.”

C, catalytic domain, M, multimerization domain; R, regulatory domain.

wwPDB Chemical Component Dictionary (49).

Disease-associated single-residue substituted variant (A313T).

Phosphorylated at Ser16.

Results

PAH Crystal Structure.

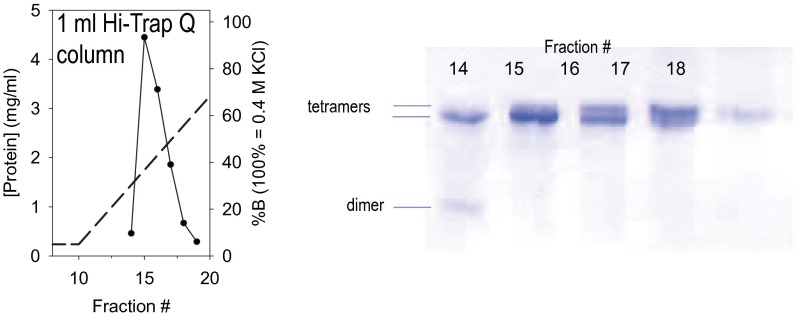

This study focuses on rat PAH, which is 96% similar (92% identical) to the human enzyme. The 15 most common disease-associated amino acids are fully conserved between rat and human, making the rodent protein an excellent model system for study of PKU. Rat PAH, heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli and purified via phenyl-Sepharose affinity chromatography (15), can be further fractionated on an ion-exchange column to partially resolve two tetrameric species (faster migrating and slower migrating) and one dimeric species, as determined by native PAGE (Fig. S1). In fractionated PAH samples, the distribution of these species is stable over long time courses, suggesting that these fractions are good starting points for crystallization trials. The faster-migrating tetramer is the predominant component in these preparations (12), and using the fraction most enriched in this species, we were able to produce well-diffracting crystals that yielded a 2.9 Å structure (Fig. 1B and Table S2), to our knowledge, the first structure for any full-length mammalian PAH. The full-length structure and the previously used composite homology model are compared in Fig. 1C [with the caveat that the composite model combined a two-domain rat PAH structure (regulatory plus catalytic) with a two-domain human PAH structure (catalytic plus multimerization) (6, 14, 16), whereas the three-domain crystal structure is rat PAH].

Fig. S1.

Ion exchange resolution of PAH assemblies. Rat PAH (28 mg), which is homogeneous by SDS/PAGE (12), is separated into different quaternary structure species using a 1-mL Hi-Trap Q column and a salt gradient. Native PAGE (PhastSystem) on individual fractions shows partial resolution of two tetrameric species and one dimeric species stained using Coomassie blue; a native Western blot shows the identical pattern of bands, with additional intensity in the dimeric species [as seen before (12)]. Fraction 15, or its equivalent from other preparations, was used for the crystallography and SAXS studies.

Table S2.

Data collection and refinement statistics for full-length rat PAH structure

| PDB code | 5DEN | |||

| Data collection | ||||

| Beamline | BNL-NSLS X25 | |||

| Wavelength, Å | 1.1 | |||

| Space group | C121 | |||

| Unit cell a, b, c, Å; β, ° | 113.78, 89.16, 196.81; 104.53 | |||

| No. of monomers in asymmetric unit | 4 | |||

| Resolution range, Å | 38.1–2.9 (3.0–2.9) | |||

| Total no. of observations | 73,766 (5,281) | |||

| No. of unique reflections | 38,661 (3,231) | |||

| Completeness, % | 91.01 (76.49) | |||

| Multiplicity | 1.9 (1.6) | |||

| <I/σ(I)> | 9.06 (1.56) | |||

| R-merge* | 0.068 (0.373) | |||

| R-meas† | 0.09 (0.529) | |||

| CC1/2 | 0.996 (0.833) | |||

| Wilson B factor, Å2 | 66.7 | |||

| Refinement | ||||

| No. of nonhydrogen atoms | 13,718 | |||

| Chain | A | B | C | D |

| Residues modeled | 22–136; 143–450 | 22–136; 143–447 | 21–136; 143–447 | 20–136; 143–449 |

| No. of waters | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| No. of Fe ions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| R-work/R-free‡ | 0.238/0.303 | |||

| No. of reflections in working set | 38,627 | |||

| No. of reflections in test set | 1,930 | |||

| Mean B factor, Å2 | 81.4 | |||

| RMS deviations | ||||

| Bonds, Å | 0.002 | |||

| Angles, ° | 0.38 | |||

| Ramachandran plot, % | ||||

| Preferred | 95.8 | |||

| Allowed | 4.2 | |||

| Outliers | 0 | |||

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

R-free is the R factor based on 5% of the data that were excluded from refinement.

The crystal asymmetric unit contains one tetramer, which adopts an autoinhibited form in which the autoregulatory region partially occludes the enzyme active site. Continuous electron density can be observed for residues 20–136 and 143–450 within each of the four protomers in the tetramer (with some variation at each termini), as well as for one iron ion per chain and two waters at the active site of each chain. The catalytic domains of the four protomers are arranged in approximate 222 symmetry, where each catalytic domain occupies one corner of a rectangle. The arrangement can be described as a dimer-of-dimers, where the dimers with the greatest buried surface area lie along the short edge of the rectangle (Fig. 1B). Although each short-edge dimer (the BD dimer or the AC dimer) is intimately assembled, the spacing between these two dimers is large, resulting in very little dimer–dimer interaction along the long edge of the tetramer, and hence a rectangular rather than square arrangement. The ACT domains extend above and below the plane of this rectangle (Fig. 1B, Bottom). The four C-terminal multimerization domains contain α-helices that assemble into an antiparallel bundle in the center of this tetrameric arrangement. The catalytic domain of each protomer contains an active site that is partly occluded by the autoregulatory region and a partially disordered active-site lid (residues ∼130–150). The conformations of the catalytic and regulatory domains of the four protomers are highly similar, with RMS deviations of ∼0.3 Å across Cα atoms. The C-terminal helices of the four protomers adopt two distinct orientations with respect to the catalytic domain, differing by a tilt of ∼10° (Fig. 1C); protomers situated across the diagonal of the tetramer contain similarly positioned helices (Figs. 1C and 2A). This asymmetry is unexpectedly different from the tetramer apparent in the two-domain human PAH structure, where similarly positioned helices are within each short-edge dimer (Fig. 2B). Because the C-terminal helices form a four-helix bundle in the center of the PAH tetramer, these differences in their positions give rise to asymmetry and cause the architecture of the tetramer to twist and deviate significantly from the bona fide 222 symmetry found in the two-domain tyrosine hydroxylase structure (Fig. 2C).

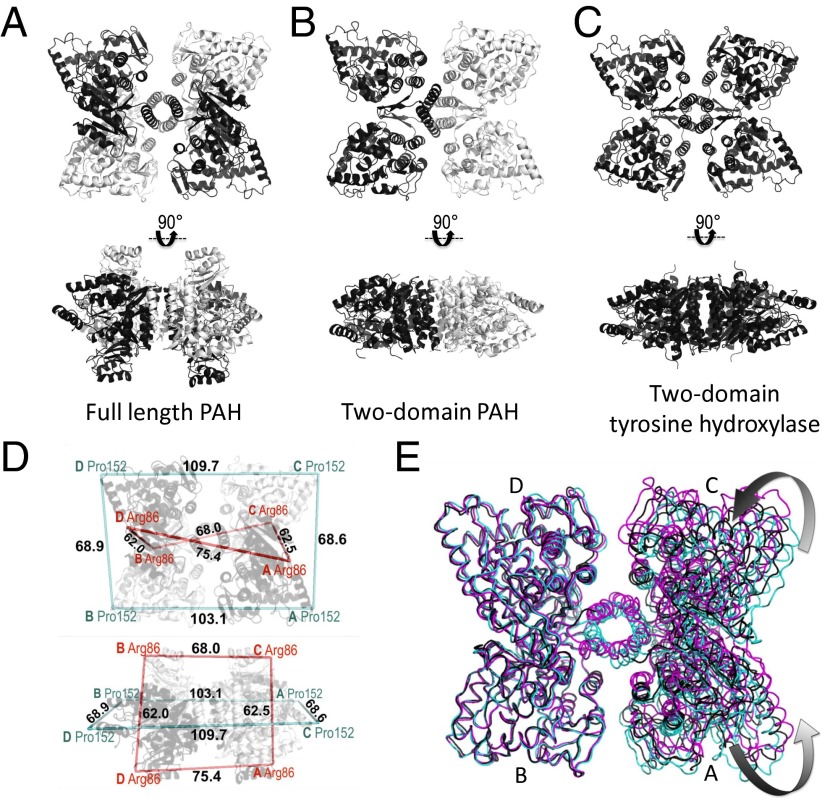

Fig. 2.

Overall architectures of PAH and related structures. (A) Structure of full-length PAH showing that subunits with similar structures (white like white, black like black) are positioned across the diagonal of the tetramer, when viewed from the perspective of the catalytic domains (Top). The regulatory domains of these similarly structured subunits are on the same side of the tetramer (Bottom). These are the subunits for which the predicted ACT domain dimerization would occur in formation of the Phe-stabilized allosterically activated tetramer. (B) The two-domain PAH tetramer (2PAH, dimer in the asymmetric unit, one white, one black), is assembled with identical subunits adjacent along the short edge of the tetramer (from the perspective of the catalytic domains). (C) The two-domain structure of tyrosine hydroxylase (1TOH, monomer in the asymmetric unit) is symmetric. (D) Representation of full-length PAH, similar to part A, showing selected distances to illustrate the asymmetry of the tetramer. (E) The 2.9 Å structure (cyan), overlaid on two other, lower resolution, structures of full-length PAH [resolutions, 3.1 Å (black) and 3.9 Å (magenta)]. The B subunits of the three structures were superposed.

The short-edge dimers form extensive interfaces (buried areas of 6,512 and 7,033 Å2 for the BC and AD dimers, respectively) between the catalytic domain of one subunit and the regulatory domain of the adjacent subunit; this interface also includes that portion of the multimerization domain that precedes the C-terminal helix. Interestingly, the short-edge dimer interface involves 8 aa whose substitutions are disease-associated, including three of the most common PKU-associated variants, I65T, R68S, and R413P. The twist between the short-edge dimers means that the other dimers (long-face and diagonal) interact predominantly through the C-terminal helices and are characterized by significantly smaller buried interfaces [the long-edge (AB and CD) and the diagonal (BC and AD) dimers bury 1,412, 766, 435, and 258 Å2, respectively]. This twist also causes the distance between the ACT domains to differ on the two faces of the tetramer; the ends of the C-terminal helices extend toward this space between the ACT domains. None of the chains are ordered all of the way to their most C-terminal residue, but the helices on the side of the tetramer with the closer ACT spacing contain more order (the C-terminal three and four residues are disordered on chains A and D, respectively, whereas the C-terminal six residues are disordered on chains B and C). Interestingly, in the two-domain human PAH structure (2PAH), the C-terminal helices are fully ordered. Thus, the twist between the short-edge dimers in the structure of full-length PAH is accompanied by a shift in the environment at the ends of C-terminal helices that no longer favors ordered packing.

The C-terminal helices form an antiparallel four-helix bundle that is the central point of tetramer association. These helices are conformationally flexible, which is evident in the nonisomorphism we observe among multiple PAH crystals. We have partially refined two additional structures for full-length PAH at lower resolution, using crystals grown under essentially identical conditions. In these structures, the position of the C-terminal helix varies, changing the relative positions of the two dimers within the tetramer (Fig. 2E). If one superposes all B subunits, the BD short-edge dimers align well, but different twists about the C-terminal helices cause positions of the AC dimers to vary by as much as ∼7 Å. This unusual level of flexibility in the PAH four-helix bundle may be responsible for some of the enzyme’s unusual kinetic characteristics, which caused us to initially identify it as a putative morpheein (17).

PAH Active-Site Access.

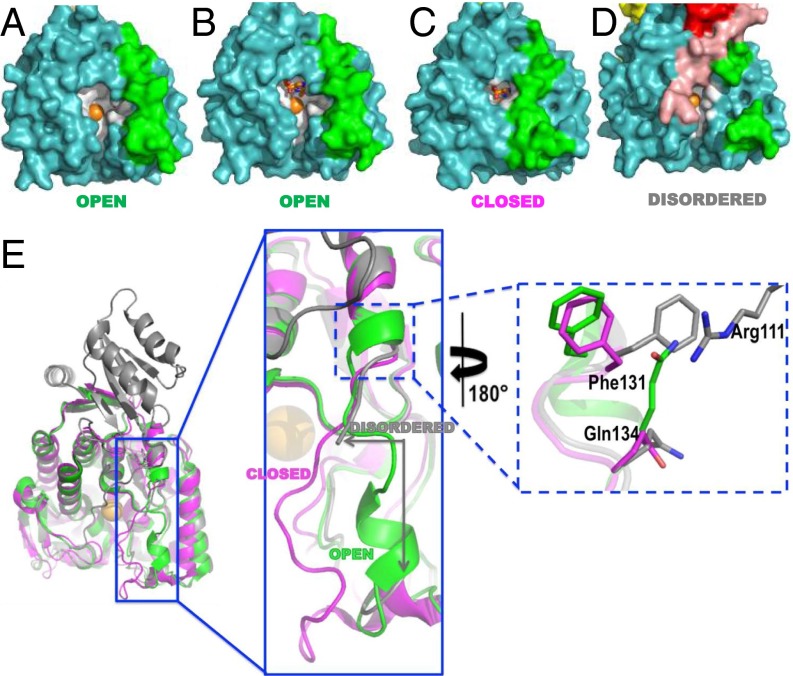

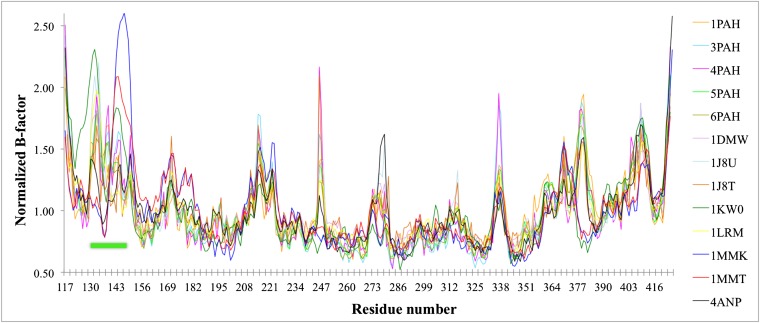

Two structural elements govern PAH active-site access, the autoregulatory region and the active-site lid. In our PAH structure, residues 20–25 of the autoregulatory region lie across the opening to the active site; we have postulated that this occlusion is relieved by a Phe-modulated formation of an ACT domain dimer (Fig. S2A) (12). The insight that regulatory domain positioning may govern active-site access sheds new light on deciphering the order of catalytic events, because previous mechanistic studies have uniformly used PAH that lacks the regulatory domain (e.g., refs. 2 and 4). The other structural element governing active-site access is an active-site lid or loop (approximately residues 130–150) (18). In all 15 structures of the isolated human PAH catalytic domain, the lid is fully ordered and exists in one of two different conformations (“open” vs. “closed”), dependent upon active-site occupancy (color coded in Table S1, illustrated in Fig. 3 A–C). The lid is open unless three different ligands are all present: iron, a Phe analog, and a pterin. In contrast, in all structures of multidomain rat and human PAH (including our structure of the full-length enzyme), the lid is partially disordered, specifically at amino acids ∼137–142 (e.g., Fig. 3D), which is the portion of the lid that differs most between the open and closed conformations. For these multidomain structures, most of the portions of the lid that can be seen align best with the open-lid conformation. However, at one point (immediately N-terminal to the disordered portion of the lid), the backbone in the multidomain structures is more closed-like than open (Fig. 3E, Left). In the single-domain structures where the lid is fully ordered, B factors for lid residues are higher than those for the rest of the structure (Fig. S3), consistent with the notion that this region is a mobile element that can change conformation—opening and closing the active site—as part of the enzyme’s catalytic function, perhaps in response to regulatory signals.

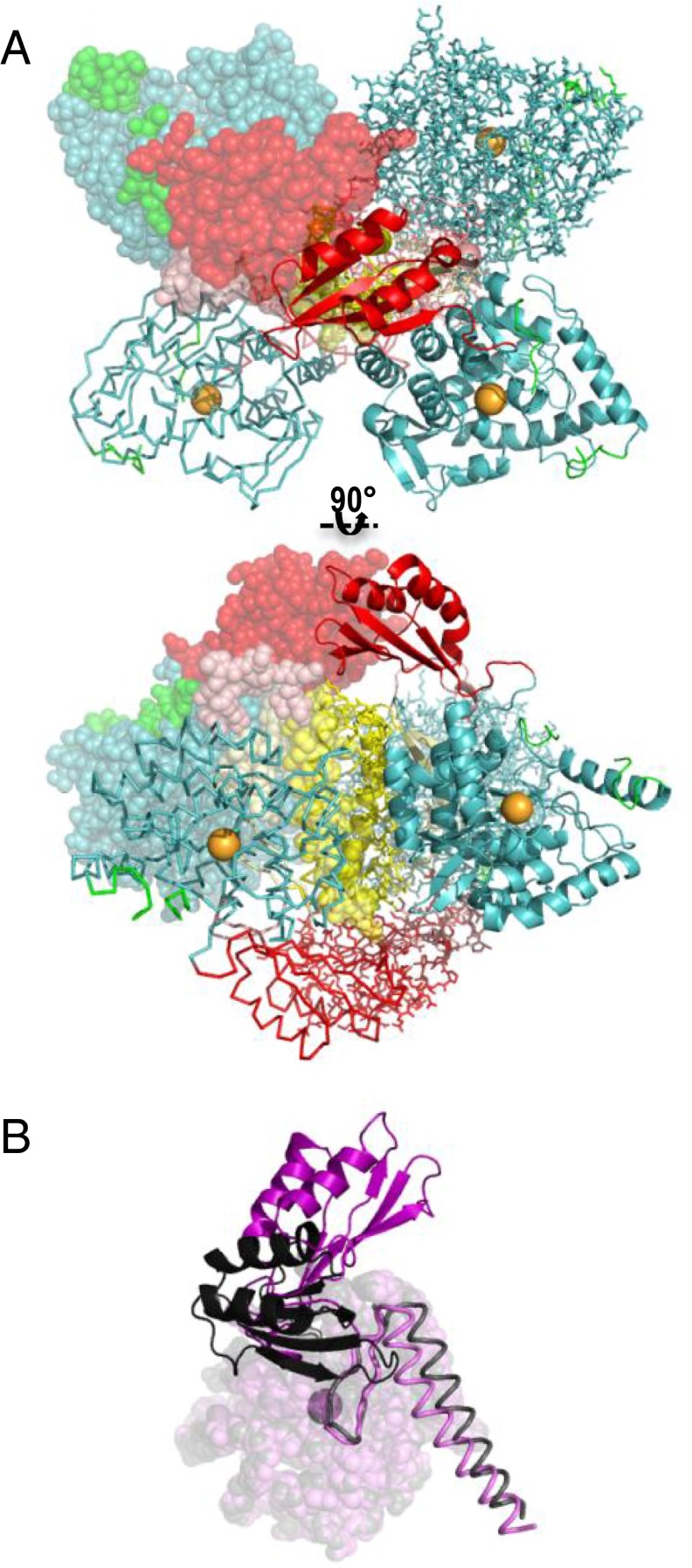

Fig. S2.

One model for an activated PAH tetramer that can be stabilized by allosteric Phe binding. (A) Orthogonal illustrations of a PAH composite tetramer model containing an ACT domain dimer interface between two subunits positioned across the diagonal of the tetramer. The putative position of the allosteric Phe binding site is within this ACT domain dimer interface. Although there is ample evidence supporting Phe stabilizing a dimerized PAH ACT domain (27, 29, 45), the details of the ACT domain dimer interface, the positioning of the C-terminal helices, which determines the relative orientations of the catalytic domains, and the conformation of the autoregulatory region can be modeled in alternate ways. Here, the catalytic and multimerization domains are modeled on the symmetric two-domain tetrameric structure of tyrosine hydroxylase (PDB ID code 1TOH, Fig. 2C) combined with our previously published PAH ACT domain dimer model (12). The program YASARA (46) was used to “refold” residues 19–33. (B) A subunit overlay (like Fig. 1C) of one subunit of the current structure (gray/black) with one subunit of a PAH model of the activated protein (light magenta/magenta). In comparing these structures, the regulatory domain, shown in a darker shade, is rotated 90° relative to the catalytic domain; this rotation relieves the conflict with the C-terminal helix (arrow in Fig. 1C).

Fig. 3.

Insight into what controls the configuration of the PAH active-site lid. (A–C) Space filling images of the catalytic domains of PAH structures colored as in Fig. 1A, with the active site (within 10 Å of the iron ion, shown as an orange sphere) colored white and active-site ligands in sticks colored by element. In all open structures, the RMS deviation between Cα positions in this lid is 0.3 Å; the corresponding value for closed structures is 0.2 Å. The highest resolution examples are used for illustration. (A) 1PAH contains only iron in the active site; (B) 1J8U contains iron and BH4; (C) 1MMT contains iron, BH4, and norleucine. (D) Positioned and colored as per parts A–C is the current crystal structure subunit D, which contains only iron in the active site. (E) An overlay of 1J8U (open, green) and 1MMT (closed, magenta) on residues 144–410 of subunit D of the current structure (disordered, gray) helps illustrate the various lid conformations. The coloring on part E corresponds to the coloring used in Table S1.

Fig. S3.

Normalized B factors for wild-type PAH structures, where the active-site lid (residues 130–150) is marked with a solid green line. B-factor values were normalized using the average B factor for each structure.

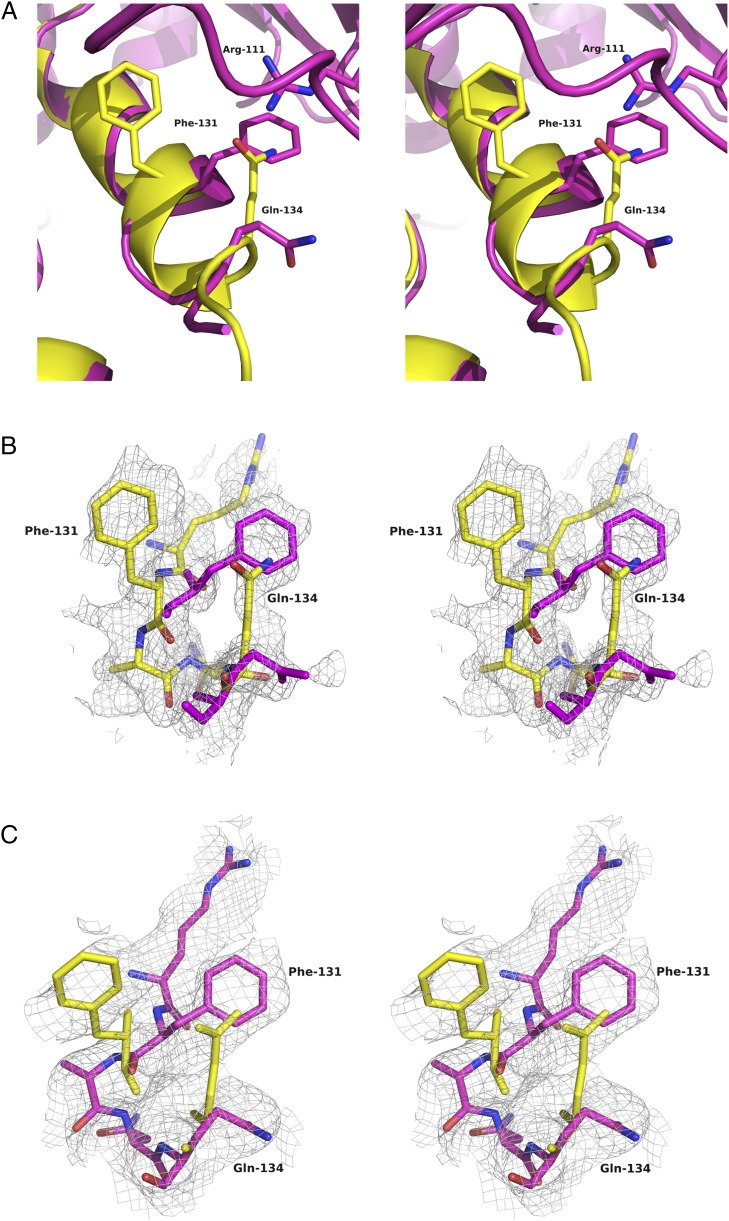

A notable difference between the structure of full-length rat PAH and those of the isolated human PAH catalytic domain is the conformation at Phe131 (Fig. 3E, Right, and Fig. S4A), which is poised to act as a hinge for the active-site lid; differences in Phe131 conformation can help rationalize the lid disorder in the full-length enzyme. For all of the single-domain structures, the backbone at Phe131 adopts one of two conformations, depending on whether the active-site lid is open or closed; however, the side-chain position remains more or less invariant. In the full-length protein, the backbone position of Phe131 is more like the closed-lid conformation, but the side chain is in a position not seen in any of the single-domain structures. This side-chain position is stabilized by a cation–π interaction between Phe131 and Arg111 (Arg111 is not ordered in any of the single-domain structures). Interestingly, the Phe131 side chain adopts this same position in the two-domain (regulatory plus catalytic) structures 1PHZ and 2PHM. Careful scrutiny of the iterative-build composite omit electron density (19) for our full-length enzyme structure suggests that a minor alternate conformation might be present for Phe131, wherein the side chain occupies the same position seen in the single-domain structures (Fig. S4C). The resolution of our data are not sufficient to confidently model minor conformers in any detail, so the map is at best suggestive. However, a 2mFo-DFc map calculated for the high-resolution PAH structure 1J8U also shows density for a potential alternate conformer for Phe131 (Fig. S4B), which would position the side chain similarly to Phe131 in the full-length structure (Fig. 3E). Thus, we propose that the side chain of Phe131, regardless of the open/closed status of the active-site lid, is able to sample two positions, one of which is stabilized by an interaction with Arg111. Because Arg111 lies at the C terminus of the ACT domain, this suggests Phe131 may serve as a hinge or toggle controlling the conformation of the active-site lid, allowing the regulatory domain to modulate access to the active site.

Fig. S4.

Possible alternate side chain positions at Phe131. (A) Superposition of the human PAH catalytic domain structure (PDB ID code 1J8U, yellow) and chain A of full-length rat PAH (PDB ID code 5DEN, magenta). This stereoview shows the vicinity of Phe131. Note that Arg111 is not present in the model for the catalytic domain structure. (B) Stereoview of a portion of the 2mFo-DFc weighted electron density map for 1J8U, contoured at 1.4σ (RMS). This map was calculated with the deposited 1J8U structure factors, using the Uppsala Electron Density Server (eds.bmc.uu.se/eds/) (47). Residues 130–135 are shown in yellow for the 1J8U catalytic domain structure; for comparison, the positions of Phe131 and Gln134 from the superimposed 5DEN model are shown in magenta. Additional density is seen to the Right of the modeled position for Phe131, which overlaps the side-chain position of Phe131 in the 5DEN structure. In the 1J8U model, the position of the Gln134 side chain would prevent Phe131 from adopting this alternate conformer, but in 5DEN the side chain of Gln134 moves down and away, removing this obstacle. (C) Stereoview of a portion of the composite iterative-build omit map generated from the 5DEN data, contoured at 0.75σ (RMS). Residues 130–135 are shown in magenta for the 5DEN full-length rat structure; for comparison, the positions of Phe131 and Gln134 from the superimposed 1J8U model are shown in yellow. The viewpoints for A–C are approximately the same.

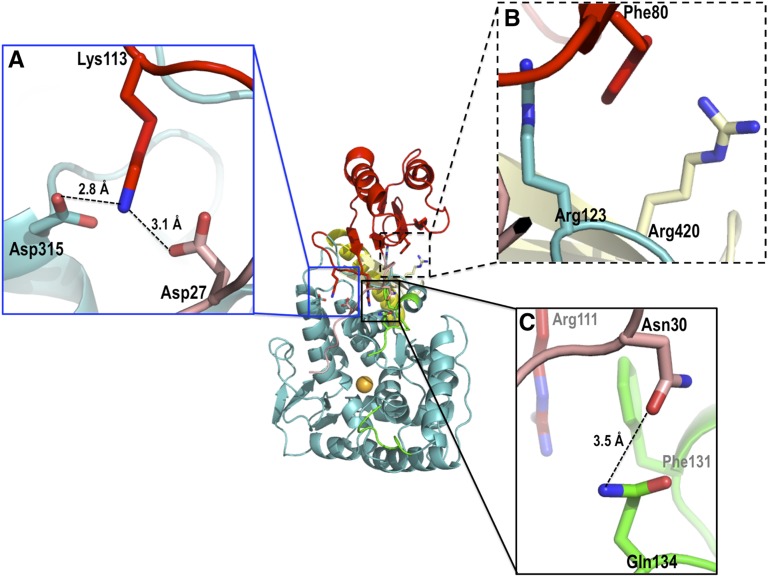

Key Interdomain Interactions.

The full-length protein structure allows us to evaluate interdomain and intersubunit interactions essential to the observed PAH tetrameric assembly. Interdomain interactions include all three PAH domains and involve (i) an H-bonding network between Lys113, Asp315, and Asp-27 (Fig. S5A); (ii) cation–π interactions between both Arg123 and Arg420 and Phe80 (Fig. S5B); (iii) an H bond between Asn30 and Gln134 (Fig. S5C); and (iv) a cation–π interaction between Arg111 and Phe131 (Fig. 3E, Right). Many of these interactions are seen in the two-domain (catalytic plus regulatory) rat PAH structure (1PHZ and 2PHM), although they were not explicitly discussed (6). All of these interdomain interactions are dependent on the position of the regulatory domain, and we predict they will be forfeited in the transition to an allosterically activated tetramer containing dimerized ACT domains.

Fig. S5.

Important interdomain interactions (colored as Fig. 1A). (A) Interactions of a hinge between the ACT subdomain (Lys113), the catalytic domain (Asp315), and a residue in the autoregulatory segment (Asp27). (B) There is a single interdomain intrachain interaction composed of two energetically favorable cation–π interactions that engages all three domains (44). (C) The autoregulatory segment (Asn30) interacts with the active-site lid via Gln134, whereas Phe131 is poised to engage in an energetically favorable cation–π interaction with Arg111 in the ACT subdomain.

SAXS Correlates the PAH Crystal Structure with the Solution Structure in the Absence of Phe and Confirms the Existence of an Architecturally Distinct Tetramer in the Presence of Phe.

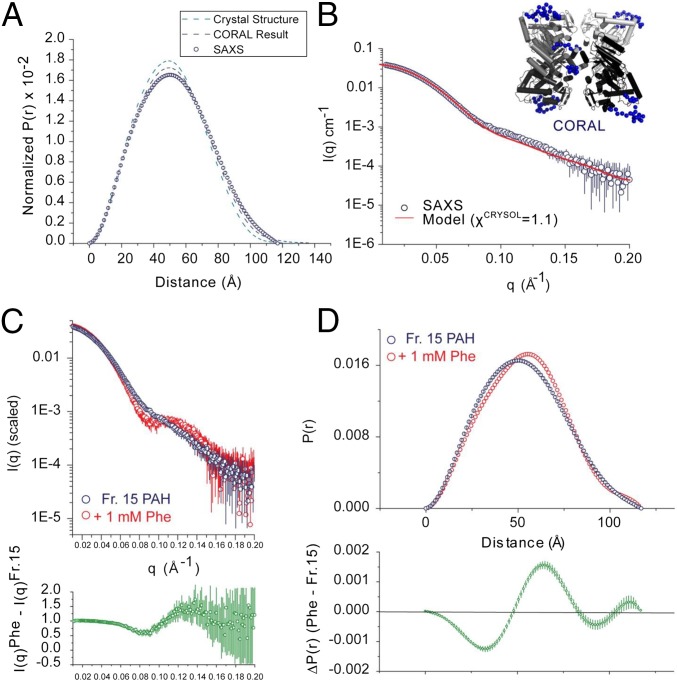

To examine the relationship between the full-length crystal structure and the oligomers of PAH that exist in solution in the absence of Phe, we performed SAXS analysis on the PAH preparations used for crystallography using size-exclusion chromatography in-line with synchrotron SAXS (20). The experimental radius of gyration (Rg), maximum interatomic distance (Dmax) (Tables S3 and S4), and pairwise shape distribution (Fig. 4A) closely match those calculated from the tetrameric crystal structure. Modeling of missing amino acids as beads on each chain was necessary for the best correlations in the higher scattering angles (χCRYSOL = 1.1–1.3 for each of 10 independent CORAL calculations) (Fig. 4A and B). These results allow us to conclude that the crystal structure is consistent with the solution structure of the PAH tetramer in the absence of Phe. However, the resolution of this approach does not preclude the existence of other, equally consistent, tetramer conformations under these conditions.

Table S3.

Parameters derived from SAXS analysis of PAH: SEC-SAXS

| MM | MM | Guinier | GNOM | ||||||||

| Source | Concentration, mg/mL | By I(0) | By Qr | qRg | Rg, Å | I(0), a.u. | Rg, Å | I(0) | Dmax, Å | Px | T.E. |

| SEC-SAXS | |||||||||||

| Fraction 15 | n.d. | n.d. | 182 | 0.50–1.29 | 40.7 ± 0.18 | 0.040 ± 0.0 | 40.5 | 0.04 | 117 | 3.9 | 0.929 |

| +1 mM Phe | n.d. | n.d. | 198 | 0.64–1.26 | 41.7 ± 0.42 | 0.043 ± 0.0 | 41.1 | 0.04 | 117 | 3.8 | 0.919 |

Table S4.

Parameters derived from SAXS analysis of PAH: Rotating anode

| MM | MM | Guinier | GNOM | ||||||||

| Source | Concentration, mg/mL | By I(0) | By Qr | qRg | Rg, Å | I(0), cm−1 | Rg, Å | I(0), cm−1 | Dmax, Å | Px | T.E. |

| Rotating anode | |||||||||||

| Fraction 15 | 3.2 | 224 | 166 | 0.46–1.31 | 43.1 ± 0.18 | 0.69 ± 0.013 | 40.3 | 0.65 | 116 | 3.6 | 0.914 |

| 2.4 | 195 | 179 | 0.45–1.29 | 42.8 ± 1.7 | 0.46 ± 0.013 | 41.1 | 0.43 | 125 | 3.8 | 0.940 | |

| 1.6 | 214 | 173 | 0.47–1.32 | 43.7 ± 2.1 | 0.33 ± 0.013 | 40.3 | 0.31 | 116 | 3.6 | 0.932 | |

| +1 mM Phe | 2.0 | 180 | 237 | 0.39–1.28 | 43.9 ± 1.7 | 0.37 ± 0.011 | 43.0 | 0.36 | 117 | 3.6 | 0.984 |

| 1.5 | 182 | 178 | 0.66–1.33 | 48.0 ± 2.8 | 0.28 ± 0.013 | 42.0 | 0.25 | 113 | 3.7 | 0.984 | |

| 1.0 | 156 | 194 | 0.62–1.52 | 41.0 ± 2.0 | 0.16 ± 0.008 | 41.9 | 0.17 | 117 | 3.9 | 0.944 | |

Fig. 4.

SAXS analyses. SAXS data obtained on the PAH tetramers in the absence of Phe is illustrated in parts A and B, and compared with the data in the presence of 1 mM Phe in parts C and D. (A) The pairwise shape distribution function [P(r)] for isolated PAH in the absence of Phe (blue circles). (B) A log–log plot (log I vs. log q) is a representative fit from CORAL rigid-body refinement (red line) vs. the experimental SAXS data (black circles) for PAH in the absence of Phe. In B and C, error bars represent the combined standard uncertainty of the data collection. A representative SAXS-refined CORAL structure is shown (Inset). The fixed atomic inventory from the crystal structure is gray, and the modeled inventory is as blue spheres. (C) A comparison of PAH before and after incubation with 1 mM Phe is shown as a superposed log–log plot (log I vs. log q) of PAH before (blue) and after (red). Using a modified χ2 (34), the Fr. 15 (-Phe) SAXS data shows a discrepancy of 0.9 vs. the crystal structure, whereas in the presence of 1 mM Phe this discrepancy increases to 2.2. Using the more discerning volatility of ratio metric [Vr, where identity is 0 and larger figures indicate higher discrepancy (34)], the Fr. 15 SAXS data show similar concordance to the structure (Vr = 4.4), whereas in the 1 mM Phe state this discrepancy increase significantly (Vr = 10.9). Shown below is a ratio plot (green), revealing discrepancy between the two profiles as a function of q; identical regions will have a ratio value of ∼1, whereas regions of higher discrepancy will have values that deviate from unity. Errors shown represent propagated counting statistics. (D) The shape distributions determined for rat PAH in the absence (blue circles) and presence (red circles) of 1 mM Phe. In the lower panel is ΔP(r) analysis (green); errors represent propagated errors from the initial inverse Fourier transform.

In the presence of 1 mM Phe (sufficient for full allosteric activation of PAH), the shape of tetrameric PAH changes significantly (Fig. 4C, Fig. S6, and Tables S3 and S4). Invariant analyses (Fig. S6 and Tables S3 and S4) suggest that the Phe-stabilized conformation is not due to significant differences in flexibility and disorder, but rather differences in the configurations of structural domains. A discrete peak feature appears in the primary data at q ∼ 0.1 Å−1 (Fig. 4C) upon Phe addition. This would correlate to a ∼60 Å length scale, which would be expected to strongly correlate with changes in interatomic distances between globular domains. By P(r) analysis, these differences coincide with increases in Rg and a redistribution of interatomic vectors to greater values (Fig. 4D and Tables S3 and S4). However, Dmax between the two states does not differ. Inspection of the difference P(r) [ΔP(r)] plot between these two states (Fig. 4D, Lower) shows a redistribution from vectors at ∼30 and ∼90 Å to vectors at ∼60 Å. The longest dimensions of the full-length PAH tetramer are defined by the arrangement of its catalytic domains approximated by a planar rectangle. Because Dmax does not change between autoinhibited and activated states, we can conclude that the overall arrangement of catalytic domains is not significantly altered, allowing us to surmise that the observed structural changes instead correlate with discrete rearrangements of the regulatory (ACT and autoregulatory) domain in each state.

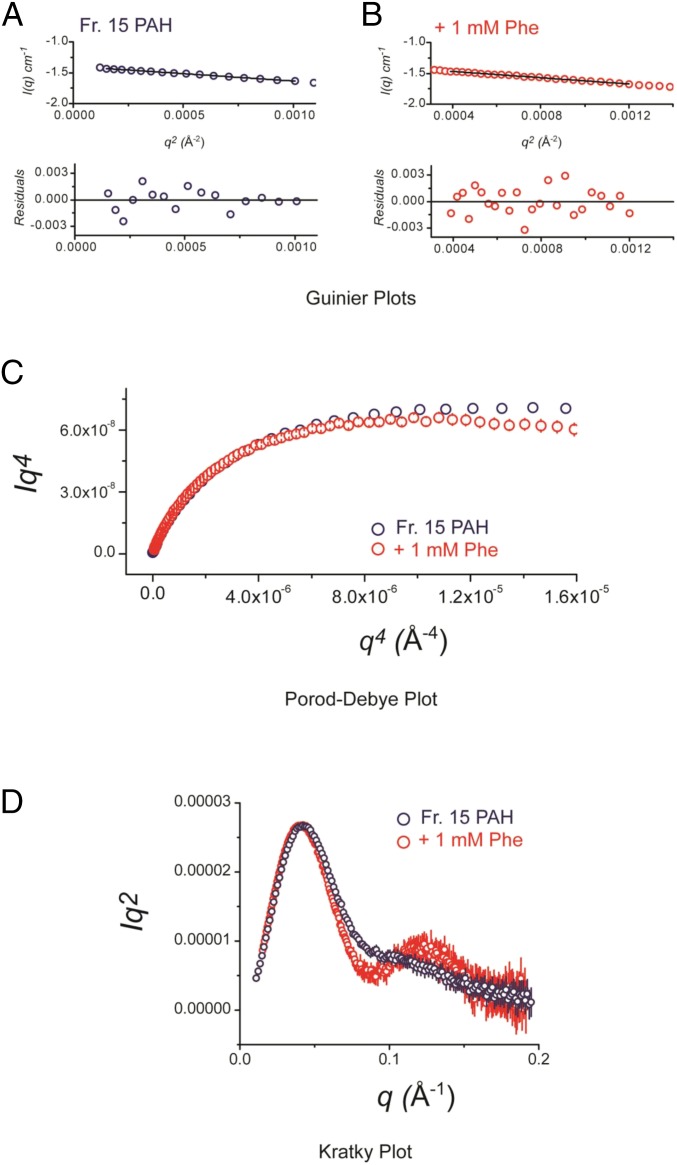

Fig. S6.

Supporting SAXS analysis. (A and B) Shown is Guinier plots analyses [ln (I) vs. q2] of PAH as isolated (A, blue) or after incubation with 1 mM Phe (B, red), with residuals from the fitting shown below the respective fits. Plots were linear and indicative of monodisperse samples. All of the preparations analyzed were monodisperse, as evidenced by linearity in the Guinier region of the scattering data and agreement of the I(0) and Rg values determined with inverse Fourier transform analysis by the programs GNOM (48). Guinier analyses were performed where qRg ≤ 1.4. When fitting manually, the maximum diameter of the particle (Dmax) was manually adjusted in GNOM to maximize the goodness-of-fit parameter, to minimize the discrepancy between the fit and the experimental data, and the visual qualities of the distribution profile. Mass determinations using the Qr invariant were determined using the program ScÅtter (https://bl1231.als.lbl.gov/scatter/). Parameters derived from this analysis are provided in Tables S3 and S4, including Rg, I(0), and the qRg range used for fitting. (C) A Porod–Debye analysis shows a plateau in the profile as a function of q4, which indicates general compactness, whereas a deviation from this asymptote as a function of q4 would indicate a loss of compactness (28) Both profiles present as compact particles, with a further gain in compactness occurring in the presence of ligand. This suggests that the Phe-stabilized conformation is not due to significant differences in flexibility and disorder, but rather discrete differences in the configurations of structural domains. (D) A Kratky plot analysis provides qualitative views of the degree of compaction of a biopolymer. For a well-folded macromolecule, a distinct peak feature at low scattering angle is typically observed, followed by a return to baseline. Unfolded biopolymers lack these features, instead increasing systematically with scattering angle. In this analysis, compact structure is indicated, consistent with the Porod–Debye analysis. In all cases, error bars on the scattering profiles represent the combined standard uncertainty of the data collection and are propagated throughout; at the lowest recorded scattering angles, this error is ∼1%.

Discussion

Full-length mammalian PAH has defied determination of a crystal structure for decades, which is not uncommon for multidomain multimeric allosteric proteins. In some instances, such proteins can accommodate alternate multimeric architectures with varying interdomain orientations (e.g., refs. 13, 17, 21, and 22). One well-studied example, PBGS, taught us that alternate conformers in a slow (or metastable) equilibrium can be separated on the basis of surface charge using ion exchange chromatography (23). This method was applied to PAH and allowed isolation of a single tetrameric species (Fig. S1), which, we believe, facilitated crystallization. The resulting structure allows the field to progress beyond a reliance on composite homology models (14).

Significant differences between the structure of full-length PAH and the composite homology model are shown in Fig. 1C, which is an overlay of the four chains of the full-length structure with the two truncated structures used to construct the composite model (1PHZ and 2PAH) (6, 16). The composite homology model correctly predicts the relative orientation of the catalytic and regulatory domains, which allows the autoregulatory region to partially occlude the enzyme active site (Fig. 1B, Top). This orientation also allows Arg111 to modulate the position of Phe131 and control the conformation of the active-site lid (Fig. 3E). However, the composite homology model incorrectly predicted the C-terminal helix positions (Fig. 1C) and the overall asymmetry of the tetramer (Fig. 2D). Careful attention to the homology model predicted a rarely referenced steric clash between one helix position and Leu72 in the ACT domain (Fig. 1C, arrow). The crystal structure reveals no such clash. However, steric interactions around Leu72 may still prove relevant, because Phe-modulated activation is predicted to include the ACT domain rotating away from the clash point (Fig. S2B); hence this site may serve as a conformational switch serving allosteric activation.

The structure of full-length PAH raises previously unasked questions, in addition to addressing some previously outstanding ones. For example, we still lack information on the conformational space available to the first ∼20 residues. Both NMR and molecular dynamics simulations suggest that the mobile N-terminal peptide can sample two distinct conformations in the absence of Phe, but prefers one of these when phosphorylated (24, 25). Mobility in this region is lost upon addition of sufficient Phe to fully activate PAH (25), suggesting that a structure of the fully active enzyme may reveal more information about this region. Also, although our structural work reveals how conformational variability in the C terminus drives differences in tetramer geometry, we have not yet deciphered the precise determinants controlling why the C-terminal helix adopts the positions it does in the two-domain PAH structure (2PAH, Fig. 2B), the tyrosine hydroxylase tetramer (1TOH, Fig. 2C) (16), or the full-length PAH structure (Fig. 2A). A related question is whether the positioning of the C-terminal helices seen in the two-domain tetramer (2PAH) reflects other tetrameric conformations of full-length PAH, for which structures are not yet known (e.g., the slower-migrating tetramer, phosphorylated PAH, and/or the allosterically activated tetramer). It is also possible that some of the conformational differences between the full-length and 2PAH structures derives from sequence differences between rat and human PAH.

One significant difference between mammalian PAH and the other aromatic amino acid hydroxylases is the sequence of the C-terminal helix. This region of tyrosine hydroxylase and tryptophan hydroxylase contains classic leucine heptad repeats, which are absent in PAH (26); neither of which shows any propensity for tetramer dissociation. The lack of a classic leucine zipper may explain not only why PAH can dissociate to dimers but also the conformational variability in the C-terminal helices (Fig. 2E).

The most significant gap in our knowledge is the structure of the activated PAH tetramer, which can putatively be stabilized by allosteric Phe binding. Because we introduced the idea that an activated tetramer contains an ACT domain dimer and that this dimer interface is the site of allosteric Phe binding (12), several new studies have provided support for this concept (27–29). We suggest a model for the activated PAH tetramer (Fig. S2A) that includes such an ACT domain dimer, similar to that of the regulatory domain of tyrosine hydroxylase (28). However, other architectures are possible, such as that of the tyrosine-binding ACT domain dimer of 3-deoxyheptulosonic acid 7-phosphate synthase (30). Also, as noted above, several possible geometries are possible for the C-terminal four-helix bundle in the activated tetramer. A third unknown regarding an activated PAH structure is the conformation of the autoregulatory region (amino acids 1–32). Our SAXS data confirm that the shape of PAH changes significantly between low and high Phe concentrations, and are consistent with a redistribution of the ACT domains. However, none of the candidate models for the high-activity PAH tetramer provides a satisfying correlation with the SAXS data at higher scattering angles, even when modeled using CORAL, emphasizing the need for additional structural efforts.

Our crystal structure of full-length PAH occupies an important position along the continuum of different PAH structures, and replaces a composite homology model as an improved context for understanding PKU-associated PAH variants. A full understanding of genotype–phenotype relationships will likely await the details of the Phe-stabilized activated PAH tetramer structure, which we have demonstrated differs significantly from that of the autoinhibited tetramer. Nevertheless, the autoinhibited structure identifies key interdomain interactions that are likely to change in the transition between autoinhibited and activated PAH tetramer.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

Full-length rat PAH was expressed in BLR-DE3 cells using a 2-d expression as described (31), with the exception that ferrous ammonium sulfate (0.2 mM) was added for the expression phase of the procedure. Protein was purified as previously described (12). Phenyl Sepharose-purified protein (28 mg) was applied to a 1-mL HiTrap Q column preequilibrated with 30 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM KCl, 15% (vol/vol) glycerol. Following a 20 column-volume wash, PAH assemblies were resolved using a linear 30 column-volume gradient to a salt concentration of 0.4 M KCl, keeping other buffer components the same. Two-milliliter fractions were collected (Fig. S1).

Crystal Growth and Crystal Structure Determination.

The protein used for crystallization was taken from a HiTrap Q column fraction highly enriched in the faster-migrating tetramer (e.g., fraction 15, Fig. S1); details for crystallization, model building, and refinement are provided in SI Materials and Methods. The structure was determined from the diffraction data collected from a single crystal at 100 K at the National Synchrotron Light Source beamline X25. Phases were obtained by molecular replacement using the highest-resolution two-domain (regulatory and catalytic) structure of rat PAH [1PHZ (6)].

SAXS Data Analysis and Modeling.

The details of data acquisition for SAXS measurements are provided in SI Materials and Methods. Modeling of the full-length PAH tetramer against its solution scatter was performed using the program CORAL (32). The known structure was fixed and inventory not resolved by crystallography were modeled using beads. Ten independent calculations in each state were performed and yielded comparable results. The final models were assessed using the program CRYSOL (33).

SI Materials and Methods

Crystallization.

Rat PAH (fraction 15 from the HiTrap Q column; Fig. S1), which had been stored at −80 °C, was thawed in a water bath at 25 °C for ∼20 min. The concentration of this protein was 9.4 mg/mL; it was diluted with 30 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 116 mM KCl, 15% glycerol to 5.5 mg/mL and left at 4 °C for ∼2 h, then at room temperature for ∼20 min, before preparing the crystallization tray. This protein solution was added 1:1 with reservoir to make a 2-µL hanging drop over a 1-mL reservoir containing 140 mM Na-acetate, 70 mM Na-citrate, 100 mM Na-cacodylate (pH 6.5), and 31.5% PEG 1000 (Hampton Research). Crystals were grown using vapor diffusion in VDX 24-well plates (Hampton Research) at room temperature. Crystals grew to full size (∼100 µm in longest dimension) within 2 d and were harvested on the third day. Crystals were cryoprotected by submerging (on-loop for ∼3 s) in a solution containing 0.5 µL of reservoir solution and 0.5 µL of a solution containing a final concentration of 50% ethylene glycol and 25% sucrose in reservoir solution before flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen for storage.

Data Collection and Processing.

Over 120 crystals (grown using the same method and crystallization conditions) were screened with synchrotron radiation at 100 K. The data used to determine this structure were collected at 100 K from a single crystal. Diffraction data were collected via the mail-in service supported by the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), at beamline X25. Data were integrated and scaled using XDS (35). Data collection statistics are reported in Table S1.

Phasing and Model Building.

Molecular replacement was performed with the program Phaser (36) using the two-domain rat PAH structure as the search model [PDB ID code 1PHZ (6)]. Refinement and all map calculations were done using the PHENIX suite (37, 38). Initially, coordinates and group B factors (two per residue) were refined. Subsequently, individual B factors and occupancies of all nonprotein atoms were refined. NCS restraints were applied throughout. In the latter stages of the refinement, two TLS groups were included per monomer and were defined as follows: group 1, N terminus through residue 115; group 2, residue 116 through C terminus. The relative weights of the X-ray and stereochemistry targets were optimized using protocols provided in the PHENIX suite. Model building was performed using Coot (39). Feature-enhanced maps (40) were used for initial model building, and iterative-build composite omit maps (19, 41) were used for subsequent model building. Stereochemical restraints affecting the active-site iron ions were generated using PHENIX. Waters around the metals were placed into positive Fo-Fc density using the 1PAH structure (42) as a guide. The geometries of the active-site metal centers were examined using the CheckMyMetal Web server (csgid.org/csgid/metal_sites/ (43), which informed manual rebuilding. Fe geometry is “borderline” (having a trigonal bipyramidal arrangement) at chains A, B, and D, and “acceptable” (having a tetrahedral arrangement) at chain C; Fe occupancy varies between 0.55 and 0.86, which is borderline for all chains. Hydrogens and conformation-dependent library restraints were added in the last stages of refinement. Model refinement statistics are reported in Table S1. The cation–π interactions were identified using the program CaPTURE (44). All molecular images were prepared using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.7.6.2, Enhanced for Mac OS X (Schrödinger).

SAXS Data Acquisition and Analysis.

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC)-SAXS data were obtained at the Australian Synchrotron SAXS/WAXS beamline. Data were collected from this 120-μm point source at a wavelength of 1.033 Å, providing an accessible scattering angle where 0.0086 < q < 0.64 Å−1 (20). One hundred microliters of 4.5 mg/mL fraction 15 PAH in 30 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 116 mM KCl, and 15% glycerol was injected onto a 3-mL Superdex 200 5/150 GL column (GE Healthcare Biosciences) equilibrated in the same buffer solution, sans glycerol. The sample was eluted isocratically at 0.15 mL/min and 25 °C into a 1-mm capillary for subsequent X-ray exposures recorded at 2-s intervals. Scattering profiles recorded at the peak size-exclusion UV intensity were chosen for subsequent analyses. The activated protein was prepared by adding 1 µL of 100 mM Phe to 100 µL of protein sample and incubating overnight at 4 °C before SEC-SAXS analysis; 1 mM Phe was included in the SEC column buffer. For analysis, data were truncated to a qmax of 0.2 to use the strongest intensity data for comparisons (I/σI ≥ 1 for q < 0.17).

Rotating anode data were recorded on a Rigaku S-Max3000 SAXS system located at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA). The instrument is equipped with Osmic mirror optics, a three-pinhole enclosed preflight path, an evacuated sample chamber with customized sample holder cryostatted at 4 °C, and a gas-filled multiwire detector; the instrument is served by a Rigaku MicroMax-007 HF microfocus rotating anode generator (Rigaku America). Protein samples (in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 116 mM KCL, and 5–15% glycerol) were spun at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C in tabletop centrifuge immediately preceding 40-min X-ray exposures. The forward scattering from the samples studied was circularly averaged to yield one-dimensional intensity profiles as a function of q (q = 4πsinθ/λ, where 2θ is the scattering angle, in units of per angstrom). Data were reduced using SAXSGui v2.05.02 (JJ X-Ray Systems ApS), and matching buffers were subtracted to yield the final scattering profile. The sample-to-detector distance and beam center were calibrated using silver behenate and intensity converted to absolute units (per centimeter) using a known polymer standard.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Thomas Scary, Ursula Ramirez, Sarah H. Lawrence, and Jinhua Wu for contributions in optimizing crystallization and cryoprotection conditions, and Mark Andrake for constructing the PAH model shown in Fig. S2A (FCCC Molecular Modeling Facility). We acknowledge SAXS data collected at the Australian Synchrotron, access provided by the New Zealand Synchrotron Group. Grant support for E.K.J. was from Developmental Therapeutics Program at the Fox Chase Cancer Center, National Cancer Institute Comprehensive Cancer Center Grant P30CA006927, and the Pennsylvania Tobacco Settlement Fund (CURE). Use of the Synchrotron at Brookhaven National Laboratory was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract DE-AC02-98CH10886. The Life-Science and Biomedical Technology Research Resource was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research (Grant P41RR012408), and by the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health (Grant P41GM103473).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 5DEN).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1516967113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Flydal MI, Martinez A. Phenylalanine hydroxylase: Function, structure, and regulation. IUBMB Life. 2013;65(4):341–349. doi: 10.1002/iub.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzpatrick PF. Mechanism of aromatic amino acid hydroxylation. Biochemistry. 2003;42(48):14083–14091. doi: 10.1021/bi035656u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman S. The phenylalanine hydroxylating system. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1993;67:77–264. doi: 10.1002/9780470123133.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts KM, Pavon JA, Fitzpatrick PF. Kinetic mechanism of phenylalanine hydroxylase: Intrinsic binding and rate constants from single-turnover experiments. Biochemistry. 2013;52(6):1062–1073. doi: 10.1021/bi301675e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzpatrick PF. Allosteric regulation of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519(2):194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobe B, et al. Structural basis of autoregulation of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6(5):442–448. doi: 10.1038/8247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scriver CR, et al. PAHdb: A locus-specific knowledgebase. Hum Mutat. 2000;15(1):99–104. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<99::AID-HUMU18>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Réblová K, Kulhánek P, Fajkusová L. Computational study of missense mutations in phenylalanine hydroxylase. J Mol Model. 2015;21(4):70. doi: 10.1007/s00894-015-2620-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wettstein S, et al. Linking genotypes database with locus-specific database and genotype-phenotype correlation in phenylketonuria. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(3):302–309. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gersting SW, et al. Loss of function in phenylketonuria is caused by impaired molecular motions and conformational instability. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(1):5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaffe EK, Stith L. ALAD porphyria is a conformational disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(2):329–337. doi: 10.1086/511444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaffe EK, Stith L, Lawrence SH, Andrake M, Dunbrack RL., Jr A new model for allosteric regulation of phenylalanine hydroxylase: Implications for disease and therapeutics. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2013;530(2):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffe EK, Lawrence SH. Allostery and the dynamic oligomerization of porphobilinogen synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519(2):144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erlandsen H, Stevens RC. The structural basis of phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;68(2):103–125. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiman R, Gray DW, Pater A. A simple purification of phenylalanine hydroxylase by substrate-induced hydrophobic chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1979;254(22):11300–11306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fusetti F, Erlandsen H, Flatmark T, Stevens RC. Structure of tetrameric human phenylalanine hydroxylase and its implications for phenylketonuria. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(27):16962–16967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selwood T, Jaffe EK. Dynamic dissociating homo-oligomers and the control of protein function. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519(2):131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daubner SC, et al. A flexible loop in tyrosine hydroxylase controls coupling of amino acid hydroxylation to tetrahydropterin oxidation. J Mol Biol. 2006;359(2):299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terwilliger TC, et al. Iterative-build OMIT maps: Map improvement by iterative model building and refinement without model bias. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;64(Pt 5):515–524. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908004319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirby NM, et al. A low-background-intensity focusing small-angle X-ray scattering undulator beamline. J Appl Cryst. 2013;46:1670–1680. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bornholdt ZA, et al. Structural rearrangement of Ebola virus VP40 begets multiple functions in the virus life cycle. Cell. 2013;154(4):763–774. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bojja RS, et al. Architecture and assembly of HIV integrase multimers in the absence of DNA substrates. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(10):7373–7386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.434431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breinig S, et al. Control of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis by alternate quaternary forms of porphobilinogen synthase. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10(9):757–763. doi: 10.1038/nsb963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miranda FF, Thórólfsson M, Teigen K, Sanchez-Ruiz JM, Martínez A. Structural and stability effects of phosphorylation: Localized structural changes in phenylalanine hydroxylase. Protein Sci. 2004;13(5):1219–1226. doi: 10.1110/ps.03595904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horne J, Jennings IG, Teh T, Gooley PR, Kobe B. Structural characterization of the N-terminal autoregulatory sequence of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Protein Sci. 2002;11(8):2041–2047. doi: 10.1110/ps.4560102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Vrana KE. Leucine zippers and coiled-coils in the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases. Neurochem Int. 1991;18(1):27–31. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(91)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang S, Roberts KM, Fitzpatrick PF. Phenylalanine binding is linked to dimerization of the regulatory domain of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Biochemistry. 2014;53(42):6625–6627. doi: 10.1021/bi501109s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Huang T, Ilangovan U, Hinck AP, Fitzpatrick PF. The solution structure of the regulatory domain of tyrosine hydroxylase. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(7):1483–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts KM, Khan CA, Hinck CS, Fitzpatrick PF. Activation of phenylalanine hydroxylase by phenylalanine does not require binding in the active site. Biochemistry. 2014;53(49):7846–7853. doi: 10.1021/bi501183x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cross PJ, Dobson RC, Patchett ML, Parker EJ. Tyrosine latching of a regulatory gate affords allosteric control of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(12):10216–10224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang L, et al. Single amino acid mutations alter the distribution of human porphobilinogen synthase quaternary structure isoforms (morpheeins) J Biol Chem. 2006;281(10):6682–6690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petoukhov MV, et al. New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Cryst. 2012;45(Pt 2):342–350. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. CRYSOL—a program to evaluate x-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J Appl Cryst. 1995;28(Pt 6):768–773. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hura GL, et al. Comprehensive macromolecular conformations mapped by quantitative SAXS analyses. Nat Methods. 2013;10(6):453–454. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kabsch W. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):133–144. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afonine PV, et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68(Pt 4):352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Afonine PV, et al. FEM: Feature-enhanced map. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2015;71(Pt 3):646–666. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714028132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Terwilliger TC, et al. Iterative model building, structure refinement and density modification with the PHENIX AutoBuild wizard. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;64(Pt 1):61–69. doi: 10.1107/S090744490705024X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erlandsen H, et al. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of human phenylalanine hydroxylase reveals the structural basis for phenylketonuria. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4(12):995–1000. doi: 10.1038/nsb1297-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng H, et al. Validation of metal-binding sites in macromolecular structures with the CheckMyMetal web server. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(1):156–170. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gallivan JP, Dougherty DA. Cation–π interactions in structural biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(17):9459–9464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Ilangovan U, Daubner SC, Hinck AP, Fitzpatrick PF. Direct evidence for a phenylalanine site in the regulatory domain of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;505(2):250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieger E, et al. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins. 2009;77(Suppl 9):114–122. doi: 10.1002/prot.22570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleywegt GJ, et al. The Uppsala electron-density server. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2240–2249. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904013253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Semenyuk AV, Svergun DI. Gnom—a program package for small-angle scattering data-processing. J Appl Cryst. 1991;24:537–540. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812007662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Westbrook JD, et al. (2015) The chemical component dictionary: Complete descriptions of constituent molecules in experimentally determined 3D macromolecules in the Protein Data Bank. Bioinformatics 31(8):1274–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]