Significance

T-cell receptor (TCR) recognition of antigenic peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins defines specificity in cellular immunity. Evidence suggests that TCRs are intrinsically biased toward MHC proteins, yet how this bias coexists alongside the considerable structural variability that is necessary for TCRs to engage different ligands has been a longstanding puzzle. By examining structural and sequence data, we found evidence that human αβ TCRs have an inherent compatibility with structural and chemical properties of MHC proteins. This compatibility leads TCRs to an intrinsic MHC bias but does not compel the formation of particular modes of binding, providing a solution to how TCRs can be MHC-biased but still structurally adaptable.

Keywords: T-cell receptor, peptide/MHC, structure, binding, MHC bias

Abstract

How T-cell receptors (TCRs) can be intrinsically biased toward MHC proteins while simultaneously display the structural adaptability required to engage diverse ligands remains a controversial puzzle. We addressed this by examining αβ TCR sequences and structures for evidence of physicochemical compatibility with MHC proteins. We found that human TCRs are enriched in the capacity to engage a polymorphic, positively charged “hot-spot” region that is almost exclusive to the α1-helix of the common human class I MHC protein, HLA-A*0201 (HLA-A2). TCR binding necessitates hot-spot burial, yielding high energetic penalties that must be offset via complementary electrostatic interactions. Enrichment of negative charges in TCR binding loops, particularly the germ-line loops encoded by the TCR Vα and Vβ genes, provides this capacity and is correlated with restricted positioning of TCRs over HLA-A2. Notably, this enrichment is absent from antibody genes. The data suggest a built-in TCR compatibility with HLA-A2 that biases receptors toward, but does not compel, particular binding modes. Our findings provide an instructional example for how structurally pliant MHC biases can be encoded within TCRs.

MHC restriction is a hallmark of T-cell recognition (1). The first crystallographic structures of T-cell receptors (TCRs) in complex with antigen revealed the structural basis for MHC restriction, illustrating how TCRs bind a composite ligand consisting of the MHC protein and its presented peptide (pMHC) (2, 3). Around the same time, evidence began to mount that T cells, and by extension their TCRs, maintain a physical bias toward MHC proteins (4). The mechanism underlying this bias, and indeed its very existence, has remained controversial. On one hand, structural evidence has been presented that germ-line complementarity-determining region (CDR) loops incorporate evolved regions with intrinsic affinities toward MHC proteins (5). On the other hand, the requirement for coreceptor during thymic selection provides a mechanism for selecting TCRs that bind MHC (6–9).

Efforts to reconcile these positions have emphasized that they are not mutually exclusive (9–11). However, it is clear that any intrinsic bias TCRs have toward MHC proteins must exist alongside the need for TCRs to structurally adapt to different ligands or alterations in the TCR–pMHC interface (12). For example, changes to a peptide alone are sufficient to alter how the same TCR sits over the same MHC protein, altering TCR–MHC atomic contacts (13, 14). Similar results are seen with changes to TCR variable domains or hypervariable loops, or even MHC mutations (15–18). Perhaps not surprisingly then, there are no germ-line–based TCR–MHC contacts that are fully conserved at the atomic level when structures with TCRs sharing the same variable domain are compared. For example, TCRs sharing Vβ 8.2 make similar contacts with the helices of the class II MHC protein I-A, but actual contacts are modulated by different peptides, hypervariable loops, and Vα domains (15, 19–21). Although such variances have been noted and even predicted (5, 22), they nonetheless make it difficult to clearly identify interactions encoding a TCR–MHC bias (12).

Furthermore, in addition to class I and class II MHC proteins, TCRs can bind a variety of nonclassical MHC molecules, non-MHC ligands (6, 23, 24), and as demonstrated very recently can even bind MHC molecules in orientations reverse from the “canonical” diagonal binding mode (25). Thus, whatever MHC biases actually do exist do not exempt a receptor from identifying alternate binding solutions or targets.

A possibility often overlooked in discussions of TCR binding is that an evolutionarily encoded MHC bias does not need to specify attractive (i.e., energetically favorable) interactions. A more fundamental feature is structural or physicochemical complementarity, or simply “compatibility.” A set of structurally/chemically compatible interactions whose formation is energetically weak, neutral, or even slightly unfavorable is better than a set of noncomplementary, unfavorable interactions. A well-understood example in protein chemistry is interactions between opposing charges in protein structures. Formation of such interactions require removal of the charges from bulk water, which comes with a substantial, unfavorable “desolvation” penalty (26, 27). The coulombic energy from the interaction between the charges is often insufficient to offset the desolvation penalty (28). However, a weak (or even unfavorable) charge–charge interaction is still energetically better than two uncompensated charges buried in a protein. In this way, charges can influence structural specificity even if they do not drive binding. Similar arguments can be made for shape complementarity: an energetically neutral but complementary set of interactions is better than a forced set of interactions that might result in steric hindrance or require costly conformational changes. This concept of compatibility is well understood in antibody–antigen interactions (29).

Considering the above arguments, evolution could have specified a TCR bias toward MHC by facilitating structural/chemical compatibility. Because they need not be energetic drivers, regions of compatibility might be expected to be adaptable and even overridden when sufficient “glue” can be found elsewhere in an interface. To examine this possibility, we studied human αβ TCRs that recognize the highly prevalent human class I MHC protein, HLA-A*0201 (HLA-A2 or simply A2). Given the high occurrence of A2 in human populations (30), we reasoned that, should it exist, a signature of evolutionarily encoded compatibility should be present within the large amount of structural data available for A2-binding TCRs. We quantified sequence variability and used this to guide queries of electrostatic compatibility. In doing so, we identified a set of interactions between TCRs and a polymorphic region on A2 that are strongly conserved in TCR–A2 structures. These interactions, which involve a positively charged polymorphic “hot-spot” region that is almost exclusive to the A2 α1-helix (31–33), are correlated not only with A2 binding but also restricted positioning over the MHC. Different TCRs engage this hot spot differently, in some cases using hypervariable rather than (or in addition to) germ-line loops. Nonetheless, we show that TCR germ-line loops are enriched in the negatively charged amino acids needed to engage the hot spot and that this enrichment is absent from the corresponding loops in antibodies. Thus, the capacity for achieving structural and chemical complementarity with A2 is not only built-in to the human TCR repertoire but present in a way that facilitates the structural adaptability needed to engage diverse pMHC ligands. Although examples of other forms of evolved compatibility remain to be identified, our findings support the conclusion that TCRs have an evolutionarily encoded, inherent compatibility with MHC proteins that facilitates recognition but does not compel particular binding solutions. This can explain how TCRs can show MHC bias in functional experiments, while still displaying considerable structural adaptability, and sometimes violate expectations.

Results

TCR Germ-Line Loops Are Diverse.

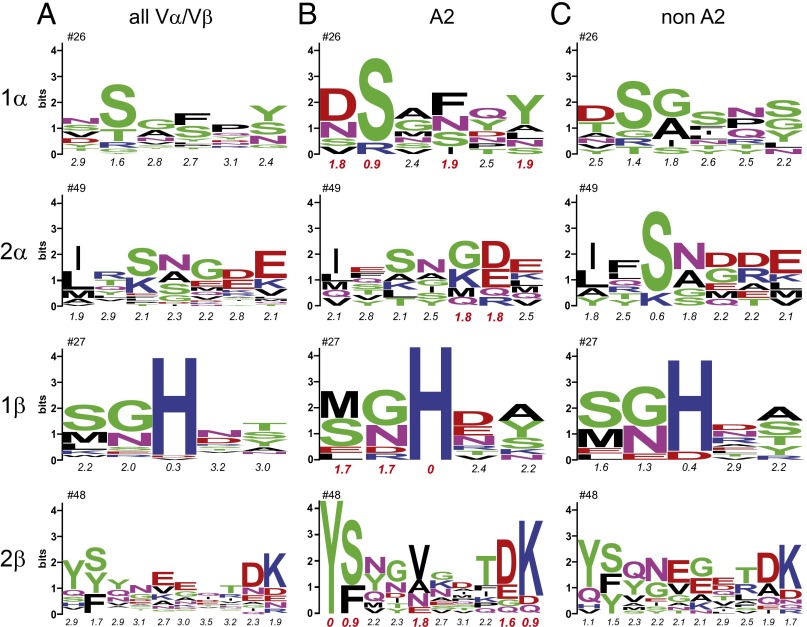

We began examining TCR germ-line loops by generating sequence logos for each CDR1 and CDR2 loop, focusing on those Vα/Vβ segments encoding the most common loop lengths (Fig. 1A; see Table S1 for loop statistics). Loop definitions and sequences were taken from the ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) database, except that we used an extended definition for CDR2β that better accounts for loop structure in structures of TCRs bound to pMHC (Fig. S1A). We also separately calculated the Shannon entropy values for each position in each loop. Shannon entropies quantify diversity, with a value of zero indicating conservation of 1 aa and the maximum value of 4.32 indicating equal representation of all 20 aa. A previous analysis of TCR variable genes identified three general Shannon entropy categories: H0 (0 ≤ H ≤ 1), H1 (1 < H ≤ 2), and H2 (H > 2) (34). H0 sites are highly conserved and associated with sites essential for fold or function. H1 sites are semiconserved, and H2 sites are highly variable with no obvious conservation pattern.

Fig. 1.

There is no sequence signature for TCR binding HLA-A2. (A) Sequence logos for the most common germ-line loop lengths in human TCR Vα/Vβ genes. The numbers at the Top give the sequence number for the first amino acid in the loop. Numbers below give Shannon entropy values for each loop position. (B) Sequence logos for the set of structurally/physically characterized human TCRs that bind A2. Red entropy numbers indicate highly conserved H0/H1 sites. (C) Sequence logos for the set of structurally characterized human TCRs that bind human class I MHC proteins other than A2.

Table S1.

TCR and antibody genes associated with each CDR loop

| Molecule | TCRs | Antibodies | ||||||

| CDR1α | CDR2α | CDR1β | CDR2β | CDR1-L | CDR2-L | CDR1-H | CDR2-H | |

| All receptors/antibodies | ||||||||

| Total number of sequences | 102 | 103 | 113 | 113 | 2,704 | 2,712 | 3,301 | 3,187 |

| No. of unique sequences | 53 | 48 | 43 | 55 | 2,385 | 772 | 1,029 | 1,202 |

| % unique sequences used for frequency calculations | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Most common loop length | 6 | 7 | 5 | 10 | ||||

| % unique sequences used for logos | 62% | 46%* | 91% | 87% | ||||

| No. of unique sequences used for logos | 33 | 22 | 39 | 48 | ||||

| A2-recognizing human αβ TCRs structurally and physically characterized | ||||||||

| Total number of sequences | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | ||||

| No. of unique sequences | 13 | 14 | 12 | 13 | ||||

| % unique sequences used for logos | 62% | 50%* | 83% | 77% | ||||

| No. of unique sequences used for logos | 8 | 7 | 10 | 10 | ||||

| Non–A2-recognizing human αβ TCRs structurally and physically characterized | ||||||||

| Total no. of sequences | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||||

| No. of unique sequences | 15 | 15 | 11 | 13 | ||||

| % unique sequences used for logos | 60% | 47%* | 100% | 100% | ||||

| No. of unique sequences used for logos | 9 | 7 | 11 | 13 | ||||

Although the most common loop length for CDR2α was 7 aa, 6-mers and 8-mers made up a more significant percentage than in other loops.

Fig. S1.

Features from the TCR structural database. (A) Mapping of IMGT loop definitions onto TCR structure. One additional amino acid was included at the N terminus and three at the C terminus of the CDR2β loop as shown in yellow. (B) CDR2β loops in structures of human TCRs that bind HLA-A2 and non–HLA-A2 adopt similar conformations. Different loop conformations cannot explain the variances in the positioning of Tyr48β along the MHC α1-helix. (C) Positions on class I MHC proteins contacted by TCRs in 35 distinct, nonredundant TCR–pMHC structures. Positions are color coded to the number of times they make at least one contact in a TCR–pMHC structure. Position 65 is contacted most frequently, along with positions 69 and 155 (outlined in yellow).

Only a single H0 site in the TCR germ-line loops was identified, the histidine at position 29 in CDR1β, whose presence has been noted previously and is thought to be involved in loop organization (35). Five H1 sites were identified, one each in CDR1α, CDR2α, and CDR1β, and two in CDR2β. The remaining sites are all H2. This indicates that the majority of TCR germ-line loop positions are highly variable, with only a small fraction demonstrating sequence and presumably functional conservation.

There Is No Obvious Signal for Engaging HLA-A2 in Sequences of TCR Germ-Line Loops.

We next asked whether binding a particular MHC protein dictates preferences in TCR germ-line loops. We assembled a set of structurally or biophysically characterized, natural human TCRs known to recognize peptides presented by the most common human class I MHC protein, HLA-A*0201 (A2) (Table S2, Complexes with HLA-A2). After accounting for duplicate genes, we used this set to compute CDR1/2 sequence logos and entropies (Fig. 1B). In all loops, diversity is reduced compared with the larger analysis of all sequences. To ask whether this result is attributable to restriction toward A2 or just reflective of a smaller sample size, we randomly generated 10 identically sized datasets of germ-line loop sequences from the larger set of all human germ-line loop sequences. The average entropies of the loops of the A2-binding TCRs were all within one SD of the averages of the randomly generated datasets, indicating that reduced diversity in the data in Fig. 1B is not likely a function of engaging A2 (Table S3).

Table S2.

Complexes of human αβ TCRs with human class I MHCs and their properties

| TCR | Complex PDB | Vα | Vβ | MHC | Notes | CDR1α | CDR2α | CDR1β | CDR2β | Crossing angle, ° | Incident angle, ° | Pos 65 SASA bound, % | Pos 65 SASA free, % | Pos 66 SASA bound, % | Pos 66 SASA free, % |

| Complexes with HLA-A2 | |||||||||||||||

| A6 | 1QRN | 12-2*01 | 6-5*01 | A*0201 | † | DRGSQS | IYSGND | MNHEY | YSVGAGITDQ | 32 | 11 | 35 | 84 | 5 | 30 |

| B7 | 1BD2 | 29/DV5 | 6-5*01 | A*0201 | NSMFDY | ISSIKDK | MNHEY | YSVGAGITDQ | 49 | 12 | 10 | 86 | 2 | 24 | |

| DMF5 | 3QDG | 12-2*01 | 6-4*01 | A*0201 | DRGSQS | IYSNGD | MRHNA | YSNTAGTTGK | 33 | 5 | 16 | 83 | 5 | 27 | |

| 1G4 | 2BNR | 21*01 | 6-5*01 | A*0201 | DSAIYN | IQSSQRE | MNHEY | YSVGAGITDQ | 69 | 16 | 23 | 87 | 7 | 22 | |

| RA14 | 3GSN | 24*01 | 6-5*01 | A*0201 | SSNFYA | MTLNGDE | MNHEY | YSVGAGITDQ | 39 | 12 | 44 | 81 | 5 | 19 | |

| E16 | 3UTT | 12-3*01 | 12-4*01 | A*0201 | NSAFQY | TYSSGN | SGHDY | YFNNNVPIDD | 47 | 9 | 19 | 78 | 0 | 23 | |

| JM22 | 1OGA | 27*01 | 19*01 | A*0201 | SVFSS | VVTGGEV | LNHDA | YSQIVNDFQK | 62 | 8 | 51 | 82 | 14 | 24 | |

| DMF4[10] | 3QDM | 35*02 | 10-3*01 | A*0201 | ‡ | SIFNT | LYKAGEL | ENHRY | YSYGVKDTDK | 30 | 5 | 47 | 81 | 6 | 29 |

| DMF4[9] | 3QEQ | 35*02 | 10-3*01 | A*0201 | ‡ | SIFNT | LYKAGEL | ENHRY | YSYGVKDTDK | 44 | 0 | 24 | 87 | 8 | 24 |

| Mel5 | 3HG1 | 12-2*01 | 30*01 | A*0201 | DRGSQS | IYSNGD | GTSNPN | YSVGIGQIS | 48 | 10 | 15 | 87 | 3 | 23 | |

| ASO1 | 3O4L | 5*01 | 20-1*01 | A*0201 | DSSSTY | IFSNMDM | DFQATT | TSNEGSKATYE | 46 | 3 | 25 | 94 | 3 | 22 | |

| α1β1ILA1 | 4MNQ | 22*01 | 6-5*01 | A*0201 | § | DSVNNL | IPSGT | MNHEY | YSIHPEYTDQ | 67 | 2 | 20 | 72 | 0 | 23 |

| C25 | 5D2N | 26-2*01 | 7-6*01 | A*0201 | TISGTDY | GLTSN | SGHVS | YFNYEAQQDK | 60 | 9 | 59 | 86 | 23 | 24 | |

| 1406 | 4ZEZ | 38-2/DV8 | 25-1*01 | A*0201 | TSESDYY | QEAYKQQ | MGHDK | YSYGVNSTEK | 30 | 17 | 37 | 66 | 4 | 12 | |

| C7 | 5D2L | 24*01 | 7-2*01 | A*0201 | ¶ | SSNFYA | MTLNGDE | SGHTA | YFQGNSAPDK | 29 | 13 | ||||

| R6C12 | 41*01 | 12-3*01 | A*0201 | # | VGISA | LSSGK | SGHNS | YFNNNVPIDD | |||||||

| NB20 | 3*01 | 6-5*01 | A*0201 | # | VSGNPY | YITGDNLV | MNHEY | YSVGAGITDQ | |||||||

| CMV1 | 35*02 | 12-4*01 | A*0201 | # | SIFNT | LYKAGEL | SGHDY | YFNNNVPIDD | |||||||

| CMV2 | 3*01 | 27*01 | A*0201 | # | VSGNPY | YITGDNLV | MNHEY | YSMNVEVTDK | |||||||

| JKF6 | 12-2*01 | 28*01 | A*0201 | # | DRGSQS | IYSNGD | MDHEN | YSYDVKMKEK | |||||||

| Complexes with other class I HLA proteins | |||||||||||||||

| TK3 | 4PRH | 20*01 | 9*01 | B*35-08 | VSGLRG | LYSAGEE | SGDLS | QYYNGEERAK | 43 | 11 | 68 | 69 | |||

| DD31 | 4QRP | 9*02 | 11-2*01 | B*08-01 | ATGYPS | ATKADDK | SGHAT | QFQNNGVVDD | 48 | 19 | 23 | 93 | |||

| 3B | 4MJI | 17*01 | 7-3*01 | B*51-01 | TSINNL | IRSNERE | SGHTA | YFQGTGAADD | 44 | 3 | 20 | 72 | |||

| C12C | 4G8G | 14/DV4*02 | 6-5*01 | B*27*05 | TSDQSYG | QGSYDEQN | MNHEY | YSVGAGITDQ | 41 | 20 | 22 | 74 | |||

| CA5 | 4JRX | 19*01 | 6-1*01 | B*35-05 | TRDTTYY | RNSFDEQN | MNHNS | YSASEGTTDK | 67 | 13 | 66 | 69 | |||

| SB47 | 4JRY | 39*01 | 5-6*01 | B*35-08 | TTSDR | LLSNGAV | SGHDT | QYYEEEERQR | 62 | 25 | 30 | 78 | |||

| C1-28 | 3VXM | 8-3*01 | 4-1*01 | A*24-02 | YGATPY | YFSGDTL | MGHRA | VYSYEKLSIN | 49 | 14 | 4 | 104 | |||

| H27-14 | 3VXR | 21*01 | 7-9*01 | A*24-02 | DSAIYN | IQSSQRE | SEHNR | YFQNEAQLEK | 51 | 8 | 52 | 103 | |||

| T36-5 | 3VXU | 12-2*02 | 27*01 | A*24-02 | DRGSQS | IYSNGD | MNHEY | YSMNVEVTDK | 60 | 3 | 4 | 103 | |||

| RL42 | 3SJV | 12-1*01 | 6-2*01 | B*08-01 | NSASQS | VYSSGN | MNHEY | YSVGEGTTAK | 37 | 4 | 38 | 71 | |||

| LC13 | 3KPR | 26-2*01 | 7-8*01 | B*44-05 | TISGTDY | GLTSN | SGHVS | YFQNEAQLDK | 41 | 15 | 51 | 90 | |||

| CF34 | 3FFC | 14/DV*01 | 11-2*01 | B*08-01 | TSDPSYG | QGSYDQGN | SGHAT | QFQNNGVVDD | 28 | 4 | 29 | 78 | |||

| AGA | 2YPL | 5*01 | 19*01 | B*57-01 | DSSSTY | IFSNMDM | LNHDA | YSQIVNDFQK | 27 | 3 | 87 | 87 | |||

| DM1 | 3DXA | 26-1*02 | 7-9*01 | B*44-05 | TISGNEY | GLKNN | SEHNR | YFQNEAQLEK | 57 | 9 | 15 | 99 | |||

| ELS4 | 2NX5 | 1-2*01 | 10-3*02 | B*35-01 | TSGFNG | NVLDGL | ENHRY | YSYGVKDTDK | 56 | 7 | 6 | 92 | |||

| SB27 | 2AK4 | 19*01 | 6-1*01 | B*35-08 | TRDTTYY | RNSFDEQN | MNHNS | YSASEGTTDK | 70 | 9 | 20 | 73 | |||

Sequences in bold throughout the table are the most common length and are included in sequence logos one time per occurrence.

DMF4[9] and DMF4[10] are the same TCR over different peptide/HLA-A2 complexes; binding orientation differs by 13°. Both structures were included in the contact analyses.

The sequence of the CDR2β loop of the α1β1ILA TCR was modified by yeast display. Complex was excluded from analysis unless otherwise indicated.

The structure with the C7 TCR is at a low resolution with missing electron density for many of the key side chains and was excluded from the contact analyses.

Structure of the complex not available.

Table S3.

Average Shannon entropies for TCR CDR loop sequences

Examining the entropy data for the A2-binding TCRs in more detail, there are at least two sites per CDR loop that are H0 or H1 (highly conserved or semiconserved; Shannon entropy values highlighted in red in Fig. 1B). For comparison, we computed sequence logos and entropies for a set of structurally characterized, natural human TCRs shown to bind human class I MHC proteins other than A2 (Fig. 1C; TCRs in Table S2, Complexes with other class I HLA proteins). Although there are notable similarities and differences, in every case, the most common amino acids in the A2-binding H0 or H1 sites are also present in the equivalent position in the non–A2-binding sequences. χ2 tests for independence indicated that the two sets of sequences are not statistically distinct. Thus, the available data indicate that there are no germ-line amino acids or amino acid sequences exclusively required for engaging A2.

TCRs That Bind HLA-A2 Show No Conserved Pairwise Amino Acid Contacts with A2 but a Propensity for Engaging a Key Molecular Contact on the MHC α1-Helix.

We next asked whether TCRs use H0 or H1 sites to form preferred contacts with particular MHC proteins. Within the set of A2-binding TCRs, excluding redundant structures with altered peptides or mutants, there are 13 high-resolution crystal structures of naturally occurring human TCRs bound to peptide/A2 complexes (Table S2, Complexes with HLA-A2). We asked whether the most common amino acid in each H0/H1 position forms common interactions with A2. For example, does the strongly conserved serine at position 27 in CDR1α (H = 0.9) commonly contact a certain residue on A2?

Of a total of 249 pairwise amino acid interactions between the germ-line loops and A2 in the entire dataset, 44 are made using amino acids in the H0/H1 positions. Of these 44, 26 are made using the most frequently occurring residues. Of these 26, although some contacts are repeated within different complexes, there are none that were common to every complex (Table 1). In some instances, the most conserved residues at the H0/H1 sites do not contact A2 at all.

Table 1.

Contacts to HLA-A2 made by the most conserved residues in the germ-line loops of A2-binding human αβ TCRs

| Loop | H0/H1 residue | HLA-A2 contact | TCR (PDB) |

| CDR1α | D26 | W167 | Mel5 (3HG1) |

| D26 | E58 | DMF5 (3QDG) | |

| S27 | W167 | B7 (1BD2) | |

| S27 | E166 | ASO1 (3O4L) | |

| Y31 | Q155 | ASO1 (3O4L) | |

| Y31 | L156 | ASO1 (3O4L) | |

| Y31 | Y159 | ASO1 (3O4L) | |

| Y31 | Q155 | E16 (3UTT) | |

| Y31 | Q155 | B7 (1BD2) | |

| CDR1β | N28 | V76 | 1G4 (2BNR) |

| H29 | V76 | DMF4[10] (3QDM) | |

| H29 | V76 | DMF4[9] (3QEQ) | |

| CDR2β | Y48 | R65 | Mel5 (3HG1) |

| Y48 | R65 | DMF5 (3QDG) | |

| Y48 | R65 | B7 (1BD2) | |

| Y48 | R65 | 1G4 (2BNR) | |

| Y48 | R65 | E16 (3UTT) | |

| Y48 | R65 | DMF4[9] (3QEQ) | |

| Y48 | Q72 | RA14 (3GSN) | |

| V52 | V56 | 1406 (4ZEZ) | |

| V52 | Q72 | JM22 (1OGA) | |

| V52 | V76 | JM22 (1OGA) | |

| D56 | R65 | 1G4 (2BNR) | |

| D56 | Q72 | RA14 (3GSN) | |

| D56 | R65 | E16 (3UTT) | |

| D56 | K68 | DMF4[9] (3QEQ) |

Contacts measured with a 4.5-Å interatomic cutoff as described in Materials and Methods.

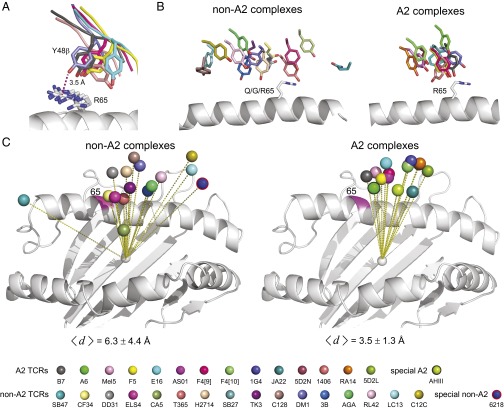

The only pattern observed in the contact analysis was between the conserved N-terminal tyrosine of CDR2β (Tyr48β) and Arg65 on the A2 α1-helix: these two residues contact each other in 6 of 13 complexes, although the numbers of contacts, their distances, and the relative positioning of the two side chains differ (Fig. 2A). This observation is consistent with earlier studies indicating a potential role for this tyrosine (22, 36). None of the interactions between Tyr48β and Arg65 involves a hydrogen bond or other electrostatic interaction, and the interaction is not restricted to a certain Vβ gene use. When in contact, the shape complementarity between Arg65 and Tyr48β ranged from moderate to high. This was quantified using the Sc statistic (37), yielding values from 0.64 for Mel5 to 0.86 for 1G4 (a value of 1.0 would indicate perfect complementarity between interacting residues).

Fig. 2.

TCRs that bind HLA-A2 are more restricted in their binding mode. (A) Alignment between Tyr48 of CDR2β and Arg65 on the A2 α1-helix in six TCR–pMHC complexes where Tyr48β and Arg65 are in contact. (B) TCRs that bind A2 place Tyr48β near position 65 on the α1 helix. The left image shows the position of residue 48β for TCRs that bind class I HLA proteins other than A2. The right image shows the Tyr48β position with A2-binding TCRs. (C) TCRs that bind A2 are more restricted in their position over the MHC, as shown by the TCR Vα/Vβ center of mass relative to the center of mass of the peptide-binding domain. The left image shows TCRs that bind class I HLA proteins other than A2; the right image shows A2 binding TCRs. The average distances between the Vα/Vβ centers of mass and the average center of mass are shown beneath each image. The color legend for TCRs is shown at the Bottom of the figure.

A Correlation Between TCR Binding Position and Engagement of HLA-A2.

The observation demonstrating a propensity for TCRs contacting Arg65 on A2 with a conserved tyrosine is notable, as position 65 is a polymorphic site that in part distinguishes HLA-A from HLA-B: position 65 is arginine in 85% of HLA-A alleles, whereas it is glutamine in 95% of HLA-B alleles and 100% of HLA-C alleles. To follow up, we examined the relationships between positions 48β and 65 in structures of TCRs bound to human class I MHC proteins other than A2, using the dataset in Table S2 (Complexes with other class I HLA proteins). Eleven of the TCRs in these 16 complexes have a tyrosine at position 48 in CDR2β, and only one of the MHC proteins has an arginine at position 65. Of the 11 non–A2-binding TCRs with a tyrosine at 48β, only one used it to contact position 65. This analysis revealed a stark difference between the A2 and the non-A2 complexes: in the non-A2 complexes, position 48β is positioned across a broad stretch of the α1-helix (Fig. 2B). This differs from the complexes with A2, in which Tyr48β is restricted to a much tighter region, even for those cases in which Tyr48β and Arg65 are not in contact. The difference in positioning is not due to TCR crossing (docking) angles: the average and SDs of the crossing angles of the A2-binding TCRs is 46 ± 14°, whereas for the non–A2-binding TCRs it is 49 ± 13° (Table S2). The variation also cannot be attributed to different loop conformations, as the CDR2β loops for all of the TCRs in Fig. 2 adopt similar conformations (Fig. S1B).

However, in examining the structures, we observed a greater variation in the global positioning of the TCRs over the MHC in the non-A2 complexes than the A2 complexes. To quantify this, we computed the center of mass of the Vα/Vβ domains over the MHC. In the non-A2 complexes, the center of mass is broadly distributed over the pMHC (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the center of mass of the A2-binding TCRs is restricted to a tighter cluster. To quantify this difference, we computed the position of the average center of mass for the A2 and non-A2 datasets and tabulated its distance from each individual TCR’s center of mass. For the A2 complexes, the average distance was 3.5 ± 1.3 Å. For the non-A2 complexes, the average distance was 6.3 ± 4.4 Å. A two-tailed Mann–Whitney test indicated these differences were significant at P ≤ 0.05. [We note that the values for the non-A2 structures include the SB47, SB27, and CA5 TCRs, which engage a “superbulged” 13-mer presented by HLA-B*3508 (38). If these are excluded from the non-A2 data, the non-A2 average distance drops to a less significant 4.9 ± 2.5 Å, highlighting the need for more structural work on recognition of long peptides (39).]

The Interaction Between Tyr48β and Arg65 Does Not Drive TCR Binding to Peptide/HLA-A2 Complexes.

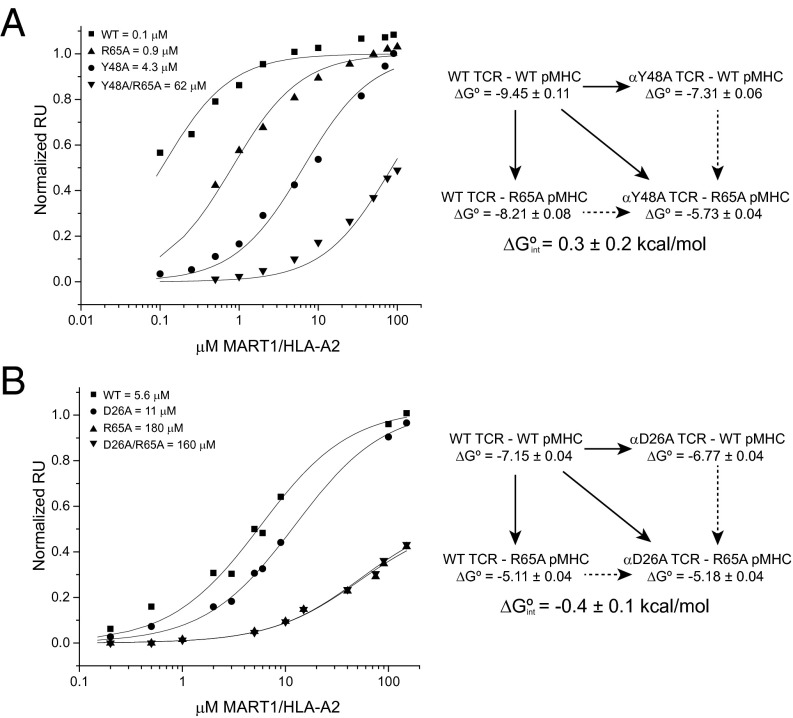

To assess the importance of the interaction between Tyr48β and Arg65 in TCR recognition of peptide/A2 complexes, we examined the impact of mutations at these positions. These were made in the interface between the TCR DMF5 and the MART126(2L)-35 peptide presented by A2, a TCR–pMHC interaction we have previously studied in detail (13, 40). The shape complementarity between Tyr48β and Arg65 in the DMF5 interface is high, with an interresidue Sc statistic of 0.8. Mutation of Tyr48β to alanine reduced binding 40-fold (ΔΔG° = 2.1 kcal/mol) (Fig. 3A). Mutation of Arg65 to alanine had a smaller but still significant effect, reducing binding eightfold (ΔΔG° = 1.2 kcal/mol). Tyr48β and Arg65 are thus clearly important for DMF5 recognition. These results are consistent with alanine mutations at these positions in other TCR–pMHC interfaces (31, 40), as well as the impact of mutations to Tyr48β on T-cell development (36).

Fig. 3.

Double-mutant cycles in the DMF5-MART1/HLA-A2 interface. (A) Double-mutant cycle between Arg65 and Tyr48β. Mutation of either Arg65 or Tyr48β to alanine weakens TCR binding, although a double-mutant cycle shows that the interaction between the two side chains is negligible. This experiment was done in the background of the affinity-enhancing D26αY/L98βW mutations in DMF5 (65). (B) Double-mutant cycle between Arg65 and Asp26α. Both mutations again have an impact on binding, although the double-mutant cycle analysis reveals a weak electrostatic interaction between the two side chains. This experiment was done in the background of the affinity-enhancing L98βW mutation in DMF5 (65).

However, the two alanine measurements do not report on the strength of the Tyr48β–Arg65 interaction. To assess this, we measured the interaction between the two alanine mutants, which when combined with the measurements for the wild type and two single mutants allowed us to construct a double-mutant cycle targeting the Tyr48β–Arg65 interaction. In a double-mutant cycle, the interaction free energy between two side chains (ΔGint) is equal to the difference between the ΔΔG° of the double mutant and the sum of the ΔΔG° values of the two single mutants (40, 41). For the interaction between Tyr48 in DMF5 and Arg65 in A2, we measured a negligible ΔGint of 0.3 kcal/mol (Fig. 3A). This indicates that, in the interface between DMF5 and A2, although both Tyr48β and Arg65 are important, the interaction between them does not provide a driving force for binding. This result is consistent with structure, as despite their high shape complementarity in the DMF5 complex, Tyr48β and Arg65 form only three van der Waals interactions. As Tyr48β and Arg65 interact similarly in all other TCR complexes with A2 (Fig. 2A; average number of contacts is 3 ± 1), this result is likely to be generally applicable.

TCRs That Bind HLA-A2 Form Electrostatic Interactions with Arg65.

We next asked whether other conservations exist between TCRs and A2 that could account for the more restricted positioning of TCRs over A2. For example, residues on the α1- or α2-helices may interact with different residues in TCR loops that nonetheless provide similar chemical complementarity. Using the set of TCR–peptide/A2 structures, we examined pairwise TCR–A2 interactions from the perspective of the MHC protein, asking which TCR amino acids interacted with each MHC amino acid on the α1- and α2-helices. We chose to focus on electrostatic interactions as these are more directional and of longer range than van der Waals interactions.

The strongest pattern that emerged from this analysis again involved Arg65 on the A2 α1-helix (Fig. 4). Arg65 forms a charge–charge interaction with a Glu or Asp near the end of CDR2β in 4 of the 13 complexes, as well as a fifth crystallized with an engineered TCR (42). Three other TCRs use a Glu or Asp at the start of CDR1α to interact with Arg65. Overall, 8 of 13 TCRs interact with Arg65 using a germ-line–encoded, negatively charged amino acid (Fig. S2 A and B).

Fig. 4.

Hydrogen bonds and charge interactions between αβ TCRs and the HLA-A2 α1/α2 helices in TCR–peptide/HLA-A2 structures. Red indicates charge–charge interactions, black indicates hydrogen bonds, and green indicates a water or ion bridge. Hydrogen bonds and charge interactions were identified as described in Materials and Methods. HLA-A2 amino acids not involved in electrostatic interactions are not shown. AHIII is a murine TCR bound to HLA-A2.

Fig. S2.

Charged interactions and hydrogen bonds with Arg65 in TCRs that bind HLA-A2 as tabulated in Fig. 4. (A) Charged interactions with CDR1α. (B) Charged interactions with CDR2β. (C) Charged interactions with CDR3α. (D) Hydrogen bonds with CDR3α. (E) Water or ion-mediated interactions linking CDR3α. Color legend is the same as used for Fig. 2 and shown below the panels.

Is this propensity for an electrostatic interaction with Arg65 reflected in germ-line loop sequences? An enrichment in negative charges in TCR CDR2β loops has been noted (22). Indeed, in the sequence logos for the A2-binding TCRs, position 56 in CDR2β and position 26 in CDR1α are low-diversity, H1 sites for which Asp and Glu are the most common amino acids (Fig. 1B). These charges are also present in the non–A2-binding TCRs, although the frequencies are lower and the positions more diverse, with H > 2 (Fig. 1C). The pattern of interacting with Arg65 is not associated with variable gene use: only two of five Vβ 6-5 TCRs use an Asp in CDR2β to interact with Arg65, and two of three Vα 12-2 TCRs use an Asp in CDR1α (Table S2, Complexes with HLA-A2). Thus, the capacity to engage Arg65 electrostatically is represented in TCRs that bind A2 and, to a lesser extent, non-A2, and it is not restricted to nor is it obligated by particular gene segments.

Expanding the search to include hypervariable loops, we observed that, in addition to germ-line loops, some TCRs use hypervariable loops to interact with Arg65. Two use only an Asp or Glu in CDR3α, and two use only noncharged CDR3α loop residues to form hydrogen bonds with Arg65 (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2 C and D). Several receptors use both germ-line and hypervariable residues. Overall, 11 of 13 TCRs directly engage Arg65 using a germ-line CDR1α/CDR2β loop or a hypervariable CDR3α loop. In the two complexes where Arg65 is not engaged directly, Arg65 interacts indirectly with a TCR polar or charged side chain via a bridging water or ion (Fig. S2E). Thus, in every structure examined, Arg65 is involved in a direct or indirect electrostatic interaction with the TCR.

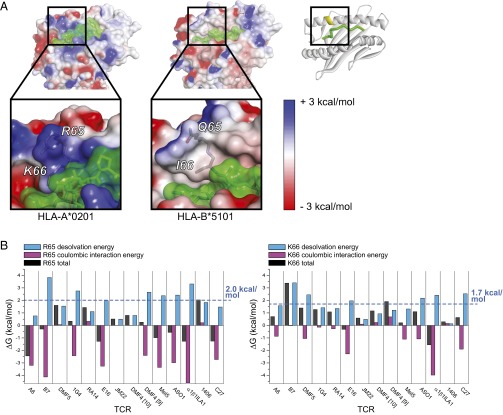

Burial of Arg65 and the Adjacent Lys66 on the HLA-A2 α1-Helix Requires Overcoming a Large Desolvation Penalty.

Position 65 is among the three most commonly contacted MHC residues in TCR interfaces with class I MHC proteins (18). This is attributable to its location near the center of the MHC α1-helix, which makes TCR burial of position 65 a near necessity (Fig. S1C). Indeed, for the A2- and non–A2-binding TCRs studied here, the average solvent accessibility of the position 65 side chain in the TCR–pMHC complex is 30%, compared with 82% in the free pMHC (Table S2, Complexes with HLA-A2). Notably, in A2, Arg65 is adjacent to another positively charged polymorphic amino acid, Lys66. In A2, the solvent accessibility of Lys66 is reduced upon TCR binding from an average of 23% to 6%. Only HLA-A alleles have the Arg65/Lys66 combination, with A2 and its suballeles accounting for 93% of the sequences. The combination of these two amino acids results in a significant and distinctive positive charge density on the surface of A2 that is absent from other MHC proteins. This is shown in Fig. 5A, which compares the electrostatic surface potentials of A2 (Arg65/Lys66) and HLA-B51 (Gln65/Ile66).

Fig. 5.

TCR burial of Arg65 and Lys66 of HLA-A2 requires overcoming a large desolvation penalty. (A) Electrostatic surface potentials mapped to the surface of HLA-A2 (Left; PDB 1DUZ) and HLA-B*5101 (Right; PDB 4MJI). Surface potentials are colored from blue to red using the indicated scale. Peptide surface is green. The ribbon diagram on the Upper Right gives the orientation of the pMHC. The regions in the square highlight the surface potentials of positions 65/66. (B) Desolvation energies, coulombic interaction energies, and total interaction energies for burial of Arg65 (Left) or Lys66 (Right) in TCR complexes with A2. The average desolvation penalty is +2.0 kcal/mol for Arg65 and +1.7 kcal/mol for Lys66 as indicated by the blue lines. Coulombic interactions shown are the sum of the intermolecular and intramolecular terms.

Burial of charged amino acids in a protein interface is always associated with a penalty resulting from the removal of water molecules interacting with the charge (26, 27). We computed this desolvation penalty for Arg65 and Lys66 in each TCR interface with A2, using a continuum electrostatics approach that yields the desolvation and coulombic energies associated with charge burial (27, 43). We used this approach previously in studying TCR recognition of pMHC, validating it with mutational and binding studies (32). Across the 13 TCR–A2 interfaces, the average desolvation penalty for Arg65 was an unfavorable +2.0 kcal/mol, ranging from +0.5 to +3.8 kcal/mol (Fig. 5B). The desolvation penalty was equally compensated by favorable coulombic interactions, which averaged −2.0 kcal/mol. We performed the same calculation for Lys66, which showed an average desolvation penalty of +1.7 kcal/mol (Fig. 5B).

These computed results are in good agreement with experimental measurements. For electrostatic interactions, the ΔGint from a double-mutant cycle reflects the interresidue coulombic interactions (28). With the A6 TCR binding Tax/A2, we previously used double-mutant cycles to measure the strength of the interaction between Arg65 and Asp99 of CDR3α (40). The experimental ΔGint was a highly favorable value of −2.8 kcal/mol. For comparison, in the A6-Tax/A2 interface, the continuum electrostatic calculations yielded a value of −3.2 kcal/mol for the intermolecular coulombic interactions with Arg65. As a second check, we performed a double-mutant cycle in the interface between Arg65 and Asp26 of CDR1α in the DMF5–MART1/A2 interface. Here, the ΔGint was −0.4 kcal/mol (Fig. 3B). For comparison, the computed intermolecular coulombic interactions of Arg65 with DMF5 amounted to 0.5 kcal/mol.

The Xenoreactive TCR AHIII Demonstrates Electrostatic Interactions with Arg65 and Lys66 Are Not Strictly Encoded.

Our analysis so far indicates that the need to interact with and counteract a region of positive charge on the A2 α1-helix is reflected in the composition of TCR germ-line sequences, and doing so is correlated with more restricted TCR positioning over pMHC. However, the utilization of both hypervariable and germ-line loops in this capacity, even with TCRs sharing variable gene segments, indicates that the germ-line sequences do not obligate particular interactions with Arg65. In other words, although TCR germ-line loops are enriched in the capacity to interact with Arg65/Lys66, inherent structural adaptability and sequence variations allow charge complementarity to occur opportunistically via a variety of means.

As a test of this hypothesis, we examined the structure of the xenoreactive mouse TCR AHIII bound to the p1049 peptide presented by A2 (44), reasoning that strict genetic programming between germ-line loops and A2 would have diverged between mice and humans, altering how Arg65 is accommodated. In this structure, however, Arg65 interacts with Glu56 in CDR2β (Fig. 4). Tyr48 of the AHIII CDR2β loop also contacts Arg65, and the TCR binds with a center of mass that falls within the range seen for other A2-binding TCRs (Fig. 2C). The “cognate” syngeneic ligand for AHIII is a peptide presented by the mouse class I MHC protein H-2Db, which notably has glutamine rather than arginine at position 65 on the α1-helix. Although efforts to crystallize the AHIII-peptide/Db complex failed, in the complex between the mouse 6218 TCR and an unrelated viral peptide presented by Db (45), the 6218 TCR does not contact position 65, and the Vα/Vβ center of mass is skewed away from the cluster associated with TCR recognition of A2 (Fig. 2C). We conclude from this analysis that neutralization of the charges on the A2 α1-helix and the impact on TCR binding modes results from opportunistic rather than “hardwired” interactions, but the opportunistic interactions are facilitated by negative charges present in TCR germ-line loops.

Evolution Has Enhanced the Ability of TCR Germ-Line Loops to Engage HLA-A2.

Although our analysis shows that TCRs are not hardwired to engage Arg65/Lys66 in predetermined ways, the ability to counteract these charges is nonetheless reflected in germ-line loop sequences. Has evolution imparted this as a way to promote—if not compel—MHC binding? We addressed this by comparing the sequences of human TCR and antibody germ-line CDR loops, using data for all functional genes from the IMGT database. Antibody and TCR genes share a common ancestral history, diverging ∼500 Mya (46). Unlike TCRs, antibodies are unrestricted in the ligands they bind, and we presumed that an imprint of evolution would be visible in the extent that TCR and antibody germ-line sequences differ, particularly in the CDR1/CDR2 germ-line loops that in TCRs complement positive charges on the A2 α1-helix.

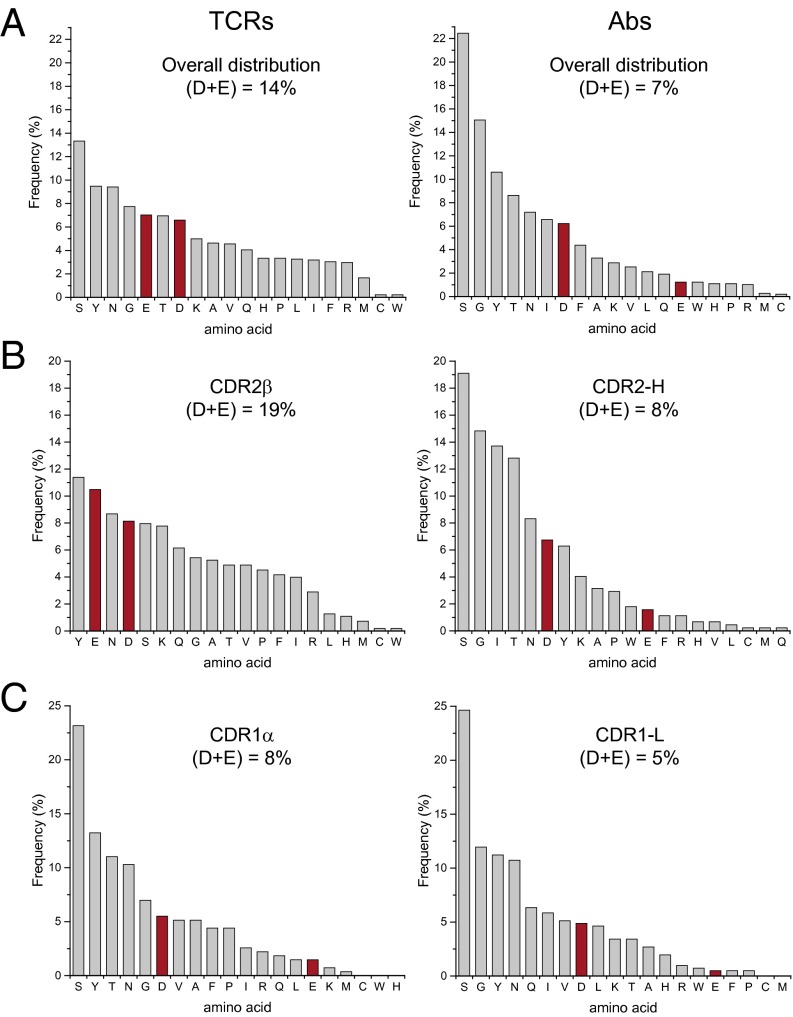

We first looked at the overall frequency of amino acids that comprise all four TCR and antibody germ-line loops. As shown in Fig. 6A, the top five amino acids for antibodies are serine, glycine, tyrosine, threonine, and asparagine. The physicochemical basis for antibody enrichment in these amino acids is well understood (47, 48). The distribution in TCR germ-line loops resembles that in antibodies, but with some distinctions. The top five amino acids are serine, tyrosine, asparagine, glycine, and notably, glutamate. Indeed, TCR germ-line loops are twice as negatively charged than those of antibodies (14% Asp/Glu in TCRs, compared with 7% in antibodies). The negative charge difference between TCRs and antibodies is statistically significant as indicated by a χ2 test (29). Studies have shown that differences between TCR and antibody gene sequences are not due to genetic drift (34).

Fig. 6.

TCR germ-line loops are enriched in negative charges compared with the corresponding antibody loops. (A) Distribution of all 20 aa in TCR (Left) and antibody (Right) germ-line loops. Total percent negative charges are shown. (B) Amino acid distributions in TCR CDR2β and antibody CDR2-H loops. (C) Amino acid distributions in TCR CDR1α and antibody CDR1-L loops.

As we have found, when using germ-line loops, TCRs that bind A2 use negative charges in CDR2β and CDR1α, in that order of preference, to offset the charge on the A2 α1-helix. We thus compared TCR and antibody germ-line CDR loops. Previous antibody/TCR sequence comparisons indicate a VH = Vβ/VL = Vα equivalence (49). The antibody equivalents to CDR2β and CDR1α are accordingly CDR2-H and CDR1-L. The amino acid distributions for these TCR and antibody loops are noticeably different, particularly in their incorporation of negative charges (Fig. 6 B and C). Negative charges account for 19% and 8% of the composition of TCR CDR2β and CDR1α loops, respectively, compared with 8% and 5% in antibody CDR2-H and CDR1-L loops. These differences remain if the domain equivalencies are switched (i.e., VH = Vα and VL = Vβ), if alternative definitions are chosen for antibody CDR loops, or whether we use the classical IMGT definition of TCR CDR2β. The strategic enrichment in negative charges in TCR CDR loops compared with antibodies suggests evolution has imprinted A2 compatibility onto TCR germ-line loops.

Discussion

TCRs have long been hypothesized to be biased toward MHC proteins, but how such a bias can exist alongside TCR structural adaptability has remained a controversial puzzle. From a structural and energetic perspective, one challenge is that atomic contacts between germ-line regions of TCRs and MHC proteins are not conserved even when the same TCR variable regions and MHC proteins are compared (22). We expanded on this here by demonstrating that, in the structural database of TCRs that bind HLA-A2, not only are there no conserved TCR–MHC contacts, even those amino acids in TCR germ-line loops that are the least variable make different contacts or do not contact A2 at all. These results are consistent with findings that diversified TCRs can still bind MHC (35), and prompted us to search for a more fundamental basis for MHC bias based upon compatibility rather than simply contacts.

Through a combination of sequence, structural, and biophysical analyses, we demonstrated that TCR germ-line loops are enriched in the means to complement a polymorphic hot-spot region on the α1-helix of the class I MHC protein HLA-A2, consisting of positively charged residues that are absent from most other HLA-A alleles, as well as those of HLA-B and HLA-C. Burial of these charges is required for TCRs to sample peptides effectively, and without the ability to complement them, their burial would be highly unfavorable due to the energetic cost of desolvation (26, 27).

Given the high frequency of A2 in human populations (30) and the recognized role of evolution in shaping TCR genes (34, 50), it is perhaps not surprising that evolution has enriched for charge complementarity with A2. Importantly, however, evolution has not selected for an exact structural solution in how to complement charges on A2. Negatively charged amino acids are found in appropriate locations in both the germ-line CDR1α and CDR2β loops, and structures show utilization of both, with some bias toward CDR2β. Moreover, hypervariable CDR3α loops can also perform this role. We suggest this reflects a built-in “permissiveness” in TCR binding. From the perspective of the TCR, the different solutions that are possible permit structural adjustments when optimizing binding with a particular peptide/A2 complex. From the perspective of the MHC, a large array of receptors will be available to engage A2, including those that lack the necessary structure and chemistry in the hypervariable CDR3α loop. Thus, evolution seems to not only have imparted MHC compatibility into the TCR repertoire, it has done so in a manner that allows structural adaptability and facilitates the cross-reactivity needed for immune function.

Does charge complementarity reflect an inherent MHC bias within TCRs? Interactions between charges in proteins are not always favorable, and indeed, our results show a range of free energies for complementing the positively charged Arg65/Lys66 pair on A2. Thus, charge complementarity will not always drive binding. However, because uncompensated buried charges will always be energetically worse than even an unfavorable charge–charge interaction, charge complementarity will influence what structures are adopted, i.e., the structural specificity of a TCR–pMHC complex. This is apparent when the structures for TCRs in complex with A2 are compared with TCRs in complex with other human class I MHC proteins: although there is structural variation in how TCRs bind A2, it is less than seen with TCRs that bind other human class I MHCs. However, does this imply a bias? Consider the outcome if negative charges in CDR2β and CDR1α were absent from the TCR repertoire: due to increased reliance on CDR3α, fewer TCRs would be compatible with A2. The greater restriction on the sequence and structure of the CDR3α loop would in turn have a negative impact on the number and type of peptides that could be recognized when presented by A2. The presence of charge complementarity between TCR germ-line loops and the A2 α1-helix therefore increases the number of TCRs available to bind, translating into an intrinsic bias.

As noted above, the distinctive charged surface of A2 and its high prevalence in human populations make it an ideal candidate for identifying contributors to MHC bias. Other features likely exist in the TCR genes that promote compatibility with MHC proteins (our analysis of hydrogen bonds and salt bridges hints at this; for example, interactions with Lys146 and Glu166 on the A2 α2-helix may deserve closer scrutiny). As demonstrated here, however, these other features need not drive binding, and each one alone need not strictly specify a binding orientation. We suggest, however, that they do allow structural and chemical complementarity to occur when thermodynamic drivers exist elsewhere in the interface, and acting together they could strongly influence binding modes. An example may be the interaction of the strongly conserved Tyr48 in CDR2β with Arg65 on A2. This interaction is energetically neutral, and indeed is not present in all structures with A2. However, in cases where it is present, it may act as a “check” on the TCR binding mode. The removal of such checks or other sites encoding compatibility from the repertoire would be expected to impact TCR recognition, explaining the negative impact on T-cell development seen with mutation of Tyr48β in mice (36).

Because our findings suggest a bias in the true sense of the word, they are broadly compatible with other results. For example, they do not exclude the possibility of TCRs binding structurally/chemically compatible non-MHC ligands, or instances in which an evolved bias is “overruled” due to unique features in a ligand or TCR. They do not rule out a role for coreceptor or thymic selection in shaping the repertoire to help select for TCR–MHC compatibility. Following this logic, it remains possible that the more restricted positioning of TCRs over A2 that emerges from charge complementarity may be functionally significant.

Materials and Methods

TCR and Antibody Sequence Analysis.

The sequences of all functional, naturally occurring, nonredundant human TCR and antibody genes were taken from the IMGT database (51). Germ-line CDR loops were selected based on the IMGT CDR definitions. For TCRs, TCR–pMHC crystallographic structures were used ensure CDR loop definitions adequately matched structural observations. For the TCR CDR2β loop, one N-terminal residue and three C-terminal residues were added to the loop definition to better fit structural observations as shown in Fig. S1A. Due to variations in the numbering of TCR residues, a uniform numbering was assigned to all HLA-A2–binding TCRs, using the B7 TCR [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1BD2] as a template (52). The numbering scheme also applies to CDR loops of the most common length. The CDR1α loop is comprised of residues 26–31, CDR2α loop is residues 49–55, CDR1β is residues 27–31, and CDR2β is residues 48–57. TCRs recognizing human class I MHC proteins were identified via PDB and the IMGT database. For sequence logos, unique sequences matching the most commonly used loop length were used as shown in Table S1. Sequence logos were created using the online WebLogo server at weblogo.berkeley.edu (53). Loop compositions in Fig. 6 used IMGT sequences for all functional TCR and antibody genes.

TCR–pMHC Structure Analysis.

Structures of human αβ TCRs in complex with human class I MHC proteins were identified and downloaded from PDB. Contacts between TCR and MHC were identified using ContPro (54), the PyMOL script DistancesRH, and Accelrys Discovery Studio 4.1, using a 4.5-Å distance cutoff. We used this more liberal cutoff distance (compared with the more common 4 Å) to better account for coordinate error and the nonstatic nature of the protein interfaces (55, 56). TCR–pMHC complexes were superimposed by the PyMOL pair fit function, fitting the α carbon of residues 1–180 of the MHC protein. The two orientations of the DMF4 TCR over the nonamer and decamer MART-1 peptides bound to HLA-A2 were analyzed separately (referred to as DMF4[9] and DMF4[10]). Hydrogen bonds were identified using Discovery Studio, using a 3.4-Å cutoff and a DHA angle range of 90–180°. Charge–charge interactions were identified using Discovery Studio with a maximum distance of 5.6 Å. This distance is greater than the 4.0 Å sometimes used for formal salt bridges, but allows for a better accounting of long-distance interactions and helps account for coordinate error and protein dynamics. In the TCR contact analysis, the structure with the C7 TCR (53) was omitted as electron density for many of the key side chains was missing. Center of mass calculations were performed for the TCR variable domains and MHC peptide-binding domains using the PyMOL center of mass script. Shape complementarity values (Sc statistic) were computed with the Sc program (37). Solvent-accessible surface areas were calculated using Discovery Studio with a 1.4-Å radius probe. Percent accessible surface areas in Table S2 are relative to the surface area of an arginine or lysine in an extended Ala-X-Ala tripeptide. TCR crossing and incident angles were calculated as described (58, 59). Literature references for each TCR–pMHC complex analyzed are listed in Table S4.

Table S4.

TCR–pMHC complexes and literature references

| Complex | PDB | Source |

| A2 complexes | ||

| A6 | 1QRN | Ref. 66 |

| B7 | 1BD2 | Ref. 52 |

| DMF5 | 3QDG | Ref. 13 |

| 1G4 | 2BNR | Ref. 67 |

| RA14 | 3GSN | Ref. 68 |

| E16 | 3UTT | Ref. 69 |

| JM22 | 1OGA | Ref. 70 |

| DMF4[10] | 3QDM | Ref. 13 |

| DMF4[9] | 3QEQ | Ref. 13 |

| Mel5 | 3HG1 | Ref. 71 |

| ASO1 | 3O4L | Ref. 72 |

| α1β1ILA1 | 4MNQ | Ref. 42 |

| 1406 | 4ZEZ | * |

| C7 | 5D2L | Ref. 57 |

| C25 | 5D2N | Ref. 57 |

| Non-A2 complexes | ||

| TK3 | 4PRH | Ref. 73 |

| DD31 | 4QRP | Ref. 74 |

| 3B | 4MJI | Ref. 62 |

| C12C | 4G8G | Ref. 75 |

| CA5 | 4JRX | Ref. 38 |

| SB47 | 4JRY | Ref. 38 |

| C1-28 | 3VXM | Ref. 76 |

| H27-14 | 3VXR | Ref. 76 |

| T36-5 | 3VXU | Ref. 76 |

| RL42 | 3SJV | Ref. 77 |

| LC13 | 3KPR | Ref. 78 |

| CF34 | 3FFC | Ref. 79 |

| AGA | 2YPL | Ref. 80 |

| DM1 | 3DXA | Ref. 81 |

| ELS4 | 2NX5 | Ref. 82 |

| SB27 | 2AK4 | Ref. 83 |

Continuum Electrostatics Calculations.

Desolvation and electrostatic interaction energies for Arg65 and Lys66 of HLA-A2 were performed using finite-difference Poisson–Boltzmann methods as previously described (32), with minor modifications as listed below. Methods of computing energies followed those of Sheinerman and Honig (43). Briefly, TCR structures were imported into Accelrys Discovery Studio. Hydrogen atoms were added and the structure’s energy minimized to optimize hydrogen placement, using 1,000 steps of steepest descent followed by 300 steps of conjugate gradient minimization using the CHARMM22 force field. Electrostatic potentials were calculated using Delphi 4.11 (26) as implemented in Discovery Studio. Solvent dielectric was set to 80 and the interior dielectric set to 10. The value of 10 for an interior dielectric was chosen based on our previous work (32) and is consistent with values used to reproduce experimental observations in other systems (60). We note, however, that although absolute values will change, our overall conclusions will be unaffected by the use of other interior dielectrics (see ref. 32, table 4). Ionic strength was set at 0.15 M. Grid spacing was 0.5 Å per point. Focusing was used, moving from 50% to 90% grid occupancy in two steps. Calculations performed on TCR–pMHC complexes and free pMHC molecules used the same grid mapping.

Desolvation penalties, intermolecular coulombic interactions, and intramolecular coulombic interactions were calculated from electrostatic potentials computed with partial charges present only on the atoms of Arg65 or Lys66 (Fig. 5B). Desolvation penalties were computed as the difference between the charging free energies of the TCR–pMHC complexes and the unbound pMHC. Intermolecular coulombic interaction energies were calculated as the interaction of the TCR–pMHC potentials with the full set of TCR partial charges. Intramolecular coulombic interaction energies were calculated similarly, except the calculation involved the full set of pMHC partial charges except those for Arg65 or Lys66, and is reported as the difference between calculations with pMHC potentials calculated for the free and TCR-bound states (43). Coulombic interaction energies reported in Fig. 5B are the sum of the intermolecular and intramolecular terms. Energies of kT reported by Delphi were converted to free energy values at 298 K. Structures for the pMHC molecules in Fig. 5A were of the Tax peptide bound to HLA-A2 (61) and an HIV 8-mer bound to HLA-B*5101 (62), and electrostatic surface potentials in this figure were calculated using all formal charges.

Protein Expression and Double-Mutant Cycles.

Soluble constructs for the A6 and DMF5 TCRs and HLA-A2 were generated from bacterially expressed inclusion bodies as previously described (63). TCRs used an engineered disulfide bridge connecting the constant domains to improve stability (64). DMF5 mutants were produced by site-directed mutagenesis and confirmed by sequencing. Peptides were purchased from Chi Scientific. Steady-state binding was measured with a Biacore 3000 instrument as previously described (63). Experiments were performed at 25 °C in 10 mM Hepes, 3 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.005% surfactant P20 at pH 7.4. Refolded and purified TCR were coupled to the surface of a CM5 sensor chip via amine linkage to a density of ∼1,500 RU.

Double-mutant cycles were performed and analyzed as described previously (40). Briefly, soluble wild-type followed by mutant pMHC complexes were injected over wild-type or mutant TCR surfaces in a series of increasing concentration points until steady-state binding was attained. Each injection series was repeated twice. In any one experiment, three flow cells were used: a blank, wild-type TCR, and mutant TCR. The output of one single experiment thus consisted of two sets of all four measurements that comprise a double-mutant cycle as shown in Fig. 3. Data were processed in BiaEvaluation 4.1, and all eight datasets were simultaneously analyzed in OriginPro 7 with a custom global fitting function. The wild-type and mutant TCR surface densities and the three ΔΔG values that make up the cycle were global fitting parameters. Errors were propagated using standard statistical error propagation methods (63). High-affinity variants of the DMF5 TCR were used to facilitate the analysis (65). For analysis of Tyr48β–Arg65 pair, the D26αY/L98βW double mutant was used. For analysis of D26α–Arg65 pair, the L98βW single mutant was used. We note that, excluding the sites of the two mutations, the structures of the high-affinity and wild-type DMF5 TCR complexes are essentially identical (13, 65). The utilization of affinity-enhancing mutations is unlikely to impact the double-mutant cycle experiments, owing to the structural similarities and the robust nature of double-mutant cycle analysis (40, 41).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Martin Flajnik and Andrew Martin for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grants GM067079 (to B.M.B.), GM103773 (to B.M.B. and Z.W.), CA154778 (to M.I.N.), CA153789 (to M.I.N.), CA180731 (to T.T.S.), and TR001108 (to T.P.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1522069113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Zinkernagel RM, Doherty PC. Immunological surveillance against altered self components by sensitised T lymphocytes in lymphocytic choriomeningitis. Nature. 1974;251(5475):547–548. doi: 10.1038/251547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garboczi DN, et al. Structure of the complex between human T-cell receptor, viral peptide and HLA-A2. Nature. 1996;384(6605):134–141. doi: 10.1038/384134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia KC, et al. An alphabeta T cell receptor structure at 2.5 Å and its orientation in the TCR-MHC complex. Science. 1996;274(5285):209–219. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zerrahn J, Held W, Raulet DH. The MHC reactivity of the T cell repertoire prior to positive and negative selection. Cell. 1997;88(5):627–636. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia KC, Adams JJ, Feng D, Ely LK. The molecular basis of TCR germline bias for MHC is surprisingly simple. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(2):143–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Laethem F, et al. Deletion of CD4 and CD8 coreceptors permits generation of alphabetaT cells that recognize antigens independently of the MHC. Immunity. 2007;27(5):735–750. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tikhonova AN, et al. αβ T cell receptors that do not undergo major histocompatibility complex-specific thymic selection possess antibody-like recognition specificities. Immunity. 2012;36(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazza C, Malissen B. What guides MHC-restricted TCR recognition? Semin Immunol. 2007;19(4):225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rangarajan S, Mariuzza RA. T cell receptor bias for MHC: Co-evolution or co-receptors? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(16):3059–3068. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1600-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Laethem F, Tikhonova AN, Singer A. MHC restriction is imposed on a diverse T cell receptor repertoire by CD4 and CD8 co-receptors during thymic selection. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(9):437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia KC. Reconciling views on T cell receptor germline bias for MHC. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(9):429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miles JJ, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J, Gras S. Understanding the complexity and malleability of T-cell recognition. Immunol Cell Biol. 2015;93(5):433–441. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borbulevych OY, Santhanagopolan SM, Hossain M, Baker BM. TCRs used in cancer gene therapy cross-react with MART-1/Melan-A tumor antigens via distinct mechanisms. J Immunol. 2011;187(5):2453–2463. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams JJ, et al. T cell receptor signaling is limited by docking geometry to peptide-major histocompatibility complex. Immunity. 2011;35(5):681–693. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stadinski BD, et al. A role for differential variable gene pairing in creating T cell receptors specific for unique major histocompatibility ligands. Immunity. 2011;35(5):694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stadinski BD, et al. Effect of CDR3 sequences and distal V gene residues in regulating TCR-MHC contacts and ligand specificity. J Immunol. 2014;192(12):6071–6082. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng L, Langley RJ, Wang Q, Topalian SL, Mariuzza RA. Structural insights into the editing of germ-line-encoded interactions between T-cell receptor and MHC class II by Vα CDR3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(37):14960–14965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207186109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burrows SR, et al. Hard wiring of T cell receptor specificity for the major histocompatibility complex is underpinned by TCR adaptability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(23):10608–10613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004926107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai S, et al. Crossreactive T cells spotlight the germline rules for alphabeta T cell-receptor interactions with MHC molecules. Immunity. 2008;28(3):324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinherz EL, et al. The crystal structure of a T cell receptor in complex with peptide and MHC class II. Science. 1999;286(5446):1913–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng D, Bond CJ, Ely LK, Maynard J, Garcia KC. Structural evidence for a germline-encoded T cell receptor-major histocompatibility complex interaction “codon.”. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(9):975–983. doi: 10.1038/ni1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marrack P, Scott-Browne JP, Dai S, Gapin L, Kappler JW. Evolutionarily conserved amino acids that control TCR-MHC interaction. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:171–203. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magarian-Blander J, Ciborowski P, Hsia S, Watkins SC, Finn OJ. Intercellular and intracellular events following the MHC-unrestricted TCR recognition of a tumor-specific peptide epitope on the epithelial antigen MUC1. J Immunol. 1998;160(7):3111–3120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castro CD, Luoma AM, Adams EJ. Coevolution of T-cell receptors with MHC and non-MHC ligands. Immunol Rev. 2015;267(1):30–55. doi: 10.1111/imr.12327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beringer DX, et al. T cell receptor reversed polarity recognition of a self-antigen major histocompatibility complex. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(11):1153–1161. doi: 10.1038/ni.3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honig B, Nicholls A. Classical electrostatics in biology and chemistry. Science. 1995;268(5214):1144–1149. doi: 10.1126/science.7761829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendsch ZS, Tidor B. Do salt bridges stabilize proteins? A continuum electrostatic analysis. Protein Sci. 1994;3(2):211–226. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosshard HR, Marti DN, Jelesarov I. Protein stabilization by salt bridges: Concepts, experimental approaches and clarification of some misunderstandings. J Mol Recognit. 2004;17(1):1–16. doi: 10.1002/jmr.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collis AVJ, Brouwer AP, Martin ACR. Analysis of the antigen combining site: Correlations between length and sequence composition of the hypervariable loops and the nature of the antigen. J Mol Biol. 2003;325(2):337–354. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen KY, Liu J, Ren EC. Structural and functional distinctiveness of HLA-A2 allelic variants. Immunol Res. 2012;53(1-3):182–190. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker BM, Turner RV, Gagnon SJ, Wiley DC, Biddison WE. Identification of a crucial energetic footprint on the α1 helix of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2 that provides functional interactions for recognition by tax peptide/HLA-A2-specific T cell receptors. J Exp Med. 2001;193(5):551–562. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.5.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gagnon SJ, et al. Unraveling a hotspot for TCR recognition on HLA-A2: Evidence against the existence of peptide-independent TCR binding determinants. J Mol Biol. 2005;353(3):556–573. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baxter TK, et al. Strategic mutations in the class I major histocompatibility complex HLA-A2 independently affect both peptide binding and T cell receptor recognition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(28):29175–29184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart JJ, et al. A Shannon entropy analysis of immunoglobulin and T cell receptor. Mol Immunol. 1997;34(15):1067–1082. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holland SJ, et al. The T-cell receptor is not hardwired to engage MHC ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(45):E3111–E3118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210882109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott-Browne JP, White J, Kappler JW, Gapin L, Marrack P. Germline-encoded amino acids in the alphabeta T-cell receptor control thymic selection. Nature. 2009;458(7241):1043–1046. doi: 10.1038/nature07812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawrence MC, Colman PM. Shape complementarity at protein/protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 1993;234(4):946–950. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu YC, et al. Highly divergent T-cell receptor binding modes underlie specific recognition of a bulged viral peptide bound to a human leukocyte antigen class I molecule. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(22):15442–15454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.447185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hassan C, et al. Naturally processed non-canonical HLA-A*02:01 presented peptides. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(5):2593–2603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.607028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piepenbrink KH, Blevins SJ, Scott DR, Baker BM. The basis for limited specificity and MHC restriction in a T cell receptor interface. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1948. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horovitz A. Double-mutant cycles: A powerful tool for analyzing protein structure and function. Fold Des. 1996;1(6):R121–R126. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(96)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cole DK, et al. T-cell receptor (TCR)-peptide specificity overrides affinity-enhancing TCR-major histocompatibility complex interactions. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(2):628–638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.522110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheinerman FB, Honig B. On the role of electrostatic interactions in the design of protein-protein interfaces. J Mol Biol. 2002;318(1):161–177. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buslepp J, Wang H, Biddison WE, Appella E, Collins EJ. A correlation between TCR Valpha docking on MHC and CD8 dependence: Implications for T cell selection. Immunity. 2003;19(4):595–606. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Day EB, et al. Structural basis for enabling T-cell receptor diversity within biased virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(23):9536–9541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106851108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flajnik MF, Kasahara M. Origin and evolution of the adaptive immune system: Genetic events and selective pressures. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(1):47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrg2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Birtalan S, et al. The intrinsic contributions of tyrosine, serine, glycine and arginine to the affinity and specificity of antibodies. J Mol Biol. 2008;377(5):1518–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shiroishi M, et al. Structural consequences of mutations in interfacial Tyr residues of a protein antigen-antibody complex. The case of HyHEL-10-HEL. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(9):6783–6791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunbar J, Knapp B, Fuchs A, Shi J, Deane CM. Examining variable domain orientations in antigen receptors gives insight into TCR-like antibody design. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(9):e1003852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bontrop RE, Otting N, Slierendregt BL, Lanchbury JS. Evolution of major histocompatibility complex polymorphisms and T-cell receptor diversity in primates. Immunol Rev. 1995;143(1):33–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1995.tb00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robinson J, et al. The IMGT/HLA database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D1171–D1176. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding YH, et al. Two human T cell receptors bind in a similar diagonal mode to the HLA-A2/Tax peptide complex using different TCR amino acids. Immunity. 1998;8(4):403–411. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia J-M, Brenner SE. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14(6):1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Firoz A, Malik A, Afzal O, Jha V. ContPro: A Web tool for calculating amino acid contact distances in protein from 3D-structures at different distance threshold. Bioinformation. 2010;5(2):55–57. doi: 10.6026/97320630005055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kass I, Buckle AM, Borg NA. Understanding the structural dynamics of TCR-pMHC complex interactions. Trends Immunol. 2014;35(12):604–612. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hawse WF, et al. TCR scanning of peptide/MHC through complementary matching of receptor and ligand molecular flexibility. J Immunol. 2014;192(6):2885–2891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang X, et al. Structural basis for clonal diversity of the public T cell response to a dominant human cytomegalovirus epitope. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(48):29106–29119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.691311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rudolph MG, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. How TCRs bind MHCs, peptides, and coreceptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:419–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pierce BG, Weng Z. A flexible docking approach for prediction of T cell receptor-peptide-MHC complexes. Protein Sci. 2013;22(1):35–46. doi: 10.1002/pro.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fitch CA, et al. Experimental pK(a) values of buried residues: Analysis with continuum methods and role of water penetration. Biophys J. 2002;82(6):3289–3304. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75670-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khan AR, Baker BM, Ghosh P, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. The structure and stability of an HLA-A*0201/octameric tax peptide complex with an empty conserved peptide-N-terminal binding site. J Immunol. 2000;164(12):6398–6405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Motozono C, et al. Molecular basis of a dominant T cell response to an HIV reverse transcriptase 8-mer epitope presented by the protective allele HLA-B*51:01. J Immunol. 2014;192(7):3428–3434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davis-Harrison RL, Armstrong KM, Baker BM. Two different T cell receptors use different thermodynamic strategies to recognize the same peptide/MHC ligand. J Mol Biol. 2005;346(2):533–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boulter JM, et al. Stable, soluble T-cell receptor molecules for crystallization and therapeutics. Protein Eng. 2003;16(9):707–711. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pierce BG, et al. Computational design of the affinity and specificity of a therapeutic T cell receptor. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(2):e1003478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ding YH, Baker BM, Garboczi DN, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Four A6-TCR/peptide/HLA-A2 structures that generate very different T cell signals are nearly identical. Immunity. 1999;11(1):45–56. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen J-L, et al. Structural and kinetic basis for heightened immunogenicity of T cell vaccines. J Exp Med. 2005;201(8):1243–1255. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gras S, et al. Structural bases for the affinity-driven selection of a public TCR against a dominant human cytomegalovirus epitope. J Immunol. 2009;183(1):430–437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bulek AM, et al. Structural basis for the killing of human beta cells by CD8+ T cells in type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(3):283–289. doi: 10.1038/ni.2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stewart-Jones GB, McMichael AJ, Bell JI, Stuart DI, Jones EY. A structural basis for immunodominant human T cell receptor recognition. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(7):657–663. doi: 10.1038/ni942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cole DK, et al. Germ line-governed recognition of a cancer epitope by an immunodominant human T-cell receptor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(40):27281–27289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miles JJ, et al. Genetic and structural basis for selection of a ubiquitous T cell receptor deployed in Epstein-Barr virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(11):e1001198. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu YC, et al. A molecular basis for the interplay between T cells, viral mutants, and human leukocyte antigen micropolymorphism. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(24):16688–16698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.563502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nivarthi UK, et al. An extensive antigenic footprint underpins immunodominant TCR adaptability against a hypervariable viral determinant. J Immunol. 2014;193(11):5402–5413. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ladell K, et al. A molecular basis for the control of preimmune escape variants by HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2013;38(3):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shimizu A, et al. Structure of TCR and antigen complexes at an immunodominant CTL epitope in HIV-1 infection. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3097. doi: 10.1038/srep03097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gras S, et al. A structural basis for varied αβ TCR usage against an immunodominant EBV antigen restricted to a HLA-B8 molecule. J Immunol. 2012;188(1):311–321. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Macdonald WA, et al. T cell allorecognition via molecular mimicry. Immunity. 2009;31(6):897–908. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gras S, et al. The shaping of T cell receptor recognition by self-tolerance. Immunity. 2009;30(2):193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stewart-Jones GB, et al. Structural features underlying T-cell receptor sensitivity to concealed MHC class I micropolymorphisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(50):E3483–E3492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207896109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Archbold JK, et al. Natural micropolymorphism in human leukocyte antigens provides a basis for genetic control of antigen recognition. J Exp Med. 2009;206(1):209–219. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tynan FE, et al. A T cell receptor flattens a bulged antigenic peptide presented by a major histocompatibility complex class I molecule. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(3):268–276. doi: 10.1038/ni1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tynan FE, et al. T cell receptor recognition of a “super-bulged” major histocompatibility complex class I-bound peptide. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(11):1114–1122. doi: 10.1038/ni1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]