Abstract

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are ligand-gated ion channels that exogenously bind nicotine. Nicotine produces rewarding effects by interacting with these receptors in the brain’s reward system. Unlike other receptors, chronic stimulation by an agonist induces an upregulation of receptor number that is not due to increased gene expression in adults; while upregulation also occurs during development and adolescence there have been some opposing findings regarding a change in corresponding gene expression. These receptors have also been well studied with regard to human genetic associations and, based on evidence suggesting shared genetic liabilities between substance use disorders, numerous studies have pointed to a role for this system in comorbid drug use. This review will focus on upregulation of these receptors in adulthood, adolescence, and development, as well as the findings from human genetic association studies which point to different roles for these receptors in risk for initiation and continuation of drug use.

Keywords: CHRN genes, review, nicotine-induced receptor upregulation, comorbid drug use, developmental changes and nAChRs

Background and Significance

Drug use

Although alcohol and tobacco use are legal, they contribute to severe and widespread problems. Worldwide, 3.3 million people die each year due to the harmful use of alcohol, representing 5.9% of worldwide deaths. Furthermore, 5.1% of the global burden of disease and injury is attributed to alcohol and recent causal relationships have been established between harmful drinking and occurrence of infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS (WHO). As of July 2015, tobacco was estimated to kill up to half of its users (WHO). In the U.S. alone, 1 in 5 deaths are attributable to smoking (CDC), and an additional 6.8 million people suffer from a serious illness caused by smoking (CDC).

Over the years spanning 2005 and 2010 between 3.4 and 6.6% of the adult population aged 15–64 used illicit drugs. Roughly 10 to 13% of these users subsequently developed drug dependence and/or a drug use disorder with high prevalence rates of serious disorders such as HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B. Illicit drug use is responsible for approximately 1 in every 100 deaths among adults (UNODC). In America illicit drug use is increasing; in 2012 9.2% of the population aged 12 or older had used an illicit drug or abused a psychotherapeutic medication in the past month. Finally, 52% of new drug users are under 18, illustrating the importance of studying these behaviors during development since most people use drugs for the first time in their teenage years (NIDA).

Evidence for shared genetic influences between different classes of drugs

Epidemiological and familial studies have shown that comorbidity among substance use disorders (SUDs, i.e. meeting abuse or dependence criteria for more than one legal or illegal drug) is high (Bierut et al., 1998, Kapusta et al., 2007, Kendler et al., 1997, Kessler et al., 1997, Merikangas et al., 1998, Pickens et al., 1995). Converging evidence from twin studies highlights the importance of genetic factors on SUDs with estimates of heritability ranging from 0.30–0.70 (Agrawal & Lynskey, 2008). Furthermore, although genetic factors specific to each substance have been identified, research has indicated that a common genetic factor underlies much of the variation in SUDs in adults (Agrawal et al., 2004, Kendler et al., 2003, Palmer et al., 2015, Palmer et al., 2012, True et al., 1999a, True et al., 1999b, Tsuang et al., 2001, Xian et al., 2008). Although work by Kendler and colleagues has implicated two underlying genetic factors with separate influences on licit and illicit drugs, these factors where shown to be highly correlated (r = 0.82) (Kendler et al., 2007). These results point to a common mechanism in the development of SUDs (Vanyukov et al., 2003).

Similar estimates have been seen for SUDs in adolescence, indicating an underlying genetic liability for substance use (Hopfer et al., 2003). Problem use has been shown to be more heritable than initiation or regular use in adolescents (Rhee et al., 2003) and twin analyses have shown significant genetic correlations for problem use across substances (Young et al., 2006). Substance use is a developmental problem that increases linearly with age (Young et al., 2002) and common genetic factors have been suggested to be particularly important for early onset SUDs that emerge in late adolescence and early adulthood (Iacono et al., 2008, Palmer et al., 2009). Similar to findings in adults, a study by Rhee and colleagues suggested two hypotheses for the comorbidity between alcohol and illicit drug dependence in adolescents: a single general liability, or two highly correlated separate liabilities (Rhee et al., 2006). Finally, tobacco has been shown to pose the greatest substance-specific risk for developing subsequent use problems (Palmer et al., 2009) and as such the remainder of this review will focus specifically on the effects of tobacco and the receptors to which it binds in the brain.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

Physiology

Although there are many compounds in tobacco smoke, nicotine is considered to be the major addictive component of tobacco smoke (Gunby, 1988, Rose, 2006, Stolerman & Jarvis, 1995). Nicotine binds muscle and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs, encoded by the CHRN genes), members of a family of ligand-gated ion channels, in the peripheral and central nervous systems (Gotti et al., 2009). They are pentameric receptors composed of various subunits ranging from alpha1-alpha10 (α1-α10) and beta1-beta4 (β1-β4) (discussed in more detail below) clustered around a central ion pore. Upon stimulation by nicotine, the five subunits undergo a conformational change causing the central pore to open, allowing extracellular ions to enter the cell. Nicotine is able to cross the blood-brain barrier and bind neuronal nAChRs in the brain (Clarke, 1987), producing rewarding effects by interacting with nAChRs in the brain’s reward system (Changeux, 2010).

Muscle nicotinic receptors

Muscle nAChRs all have the same pentameric stoichiometry of (α1)2β1δγ (fetal-type) or (α1)2β1δγ (adult-type) (Le Novere et al., 2002). Although primarily known to be expressed in muscle tissue, previous work has suggested that subunits of these receptors are also present in mammalian ciliary ganglia (Pugh et al., 1995), vestibular and cochlear hair cells (Scheffer et al., 2007), as well as brain regions such as the cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum (Ghedini et al., 2010). In addition, a splice variant of the α1 subunit was shown to expressed in numerous locations including brain, kidney, heart, liver, lung, and thymus in humans (Talib et al., 1993).

Neuronal nicotinic receptors

Neuronal nAChRs are comprised of combinations of the α2-α10 and β2-β4 subunits with variable stoichiometry that are expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems, located both presynaptically and postsynaptically (Millar & Gotti, 2009). All of the subunits are expressed in the mammalian central nervous system with the exception of the α8 subunit, which is only expressed in chicks (Britto et al., 1992, Schoepfer et al., 1990). Neuronal nAChRs can assemble in two ways; they can form homomeric receptors in which all five subunits are the same (α7, α9), or they can form heteromeric receptors in which the five subunits that make up the functional receptor include different α and β subunit combinations, which yield different pharmacological properties.

In the mammalian system, α7 and α9 subunits form homomeric receptors when expressed as isolated subunits in cells (Couturier et al., 1990, Elgoyhen et al., 1994, Schoepfer et al., 1990). The α10 subunit, although it cannot form a functional homomeric receptor, is most closely related to the α9 subunit and forms a functional receptor when coexpressed with the α9 subunit (Elgoyhen et al., 1994, Lustig et al., 2001, Sgard et al., 2002). In the central nervous system, the α9 and α10 subunits have been primarily identified in the inner ear cells, particularly the cochlear and vestibular hair cells (Elgoyhen et al., 1994, Elgoyhen et al., 2001, Luo et al., 1998, Lustig et al., 1999, Lustig et al., 2001, Vetter et al., 1999), as well as the pituitary (Sgard et al., 2002). The α7 subunit, however, is widely expressed throughout the mammalian central nervous system (reviewed in (Millar & Gotti, 2009)).

The rest of the neuronal nAChR subunits form heteromeric receptors consisting of α and β subunits (Anand et al., 1991, Boulter et al., 1987, Deneris et al., 1988, Wada et al., 1989). For heteromeric receptors, subunit composition varies, as does assembly; furthermore, the variable stoichiometry confers differences in calcium permeability and agonist and antagonist sensitivity between different receptors (Luetje & Patrick, 1991) (reviewed in (Millar & Gotti, 2009)). Studies have shown that α2-α4 and β2 and β4 subunits can form functional receptors when expressed as a pair-wise combination of one α subunit and one β subunit; functional expression has been observed for α2β4, α3β2, α3β4, α4β2, and α4β4 combinations (Duvoisin et al., 1989, Papke et al., 1989). The β3 and α5 subunits cannot form functional nAChRs unless expressed in combination with another α and β subunit pair, as neither of these possesses a binding site for an agonist or antagonist. Electrophysiological approaches have been used to distinguish triple pair subunits from pair subunits and subsequently identified receptors composed of the α3β2α5 (Gerzanich et al., 1998, Wang et al., 1996), α3β4α5 (Fucile et al., 1997, Gerzanich et al., 1998, Wang et al., 1996), and α4β2α5 (Ramirez-Latorre et al., 1996) subunits. In addition, the β3 subunit has been shown to co-assemble into a functional receptor composed of α3β3β4 subunits in oocytes (Groot-Kormelink et al., 1998), and may promote expression and stability of human α6 subunits in transfected cell lines (Tumkosit et al., 2006). Expression studies have also demonstrated that the α6 subunit assembles into functional triplet receptors, including α6β3β4 (Kuryatov et al., 2000, Tumkosit et al., 2006), as well as α3α6β4 and α3α6β2 (Fucile et al., 1998, Kuryatov et al., 2000) subunit combinations. Lastly, α6 and β2 combinations have also been observed, particularly as α4α6β2β3 and α6β2β3 receptors (Salminen et al., 2004). While neuronal nAChRs are widespread throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems, α4β2 (Anand et al., 1991, Flores et al., 1992, Wada et al., 1989) receptors are the most abundant heteromeric receptors in the brain and have the highest affinity for nicotine (Wonnacott, 1990).

Upregulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

The response of nicotinic receptors during chronic exposure to agonists has been referred to as a paradox (Wonnacott, 1990), since they do not behave as other receptors during chronic exposure to an agonist. Note that an agonist binds and activates a receptor whereas an antagonist binds and blocks receptor activation. Numerous studies have shown that chronic exposure of a receptor to an antagonist typically leads to upregulation, or an increased number of receptors, while chronic exposure of a receptor to an agonist causes downregulation, or a decreased number of receptors (Creese & Sibley, 1981, Wonnacott, 1990). However, this phenomenon is not observed with some subtypes of nAChRs, most notably, the α4β2 nAChR. Upon extended exposure of nAChRs to an agonist, α4β2 receptor numbers are upregulated. It is important to clarify that for the purposes of this discussion, upregulation refers to an increase in receptor numbers (e.g. not upregulation of mRNA), and the studies mentioned below have focused exclusively on measuring protein levels to assess the number of nAChRs.

Early studies on the brains from rats (Schwartz & Kellar, 1983) and mice (Marks et al., 1983) repeatedly exposed to nicotine showed an increase in [3H]acetylcholine and (−)-[3H]nicotine binding, two radiolabeled nAChR ligands that predominantly measure α4β2 nAChRs. Schwartz and Kellar treated rats with 2 mg/kg of nicotine twice a day for 10 days and observed an increase in [3H]acetylcholine binding in cerebral cortex of rats (Schwartz & Kellar, 1983). Similarly, Marks et al. (1983) chronically infused mice with 5 mg/kg/hr nicotine for 8–10 days (mice are less sensitive to the effects of nicotine than rats are (Matta et al., 2007), accounting for the difference in nicotine treatments in these two experiments) and reported an increase in (−)-[3H]nicotine binding in the cortex, midbrain, hindbrain, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, but not striatum (Marks et al., 1983). These results were confirmed in human post mortem brains in 1988. By measuring (−)-[3H]nicotine binding in smokers compared to nonsmokers, Benwell and colleagues demonstrated that smokers showed higher levels of (−)-[3H]nicotine binding in most grey areas including the hippocampus, cortex, gyrus rectus and median raphe nucleus, with the exception of the medulla oblongata which showed no changes in (−)-[3H]nicotine binding. Importantly, in the areas where smoking was associated with increased (−)-[3H]nicotine binding, radiolabeled ligand binding increased by 50–100% (Benwell et al., 1988). In all three of the above studies, increased radiolabeled ligand binding was confirmed to be due to an increase in receptor number, rather than an increase in binding affinity (Benwell et al., 1988, Marks et al., 1983, Schwartz & Kellar, 1983). Thus, under chronic nicotine exposure, α4β2 nAChRs undergo a nicotine-induced upregulation of receptor numbers at the membrane.

Subsequent studies provided evidence that when nicotine exposure is ceased, decreased binding of (−)-[3H]nicotine occurs after 7–10 days in mice (Marks et al., 1985), 15–20 days in rats (Collins et al., 1990), and between 21 days and 2 months in humans (Breese et al., 1997, Mamede et al., 2007). In humans, nAChR upregulation was additionally shown to be dose-dependent (Breese et al., 1997, Perry et al., 1999). Gopalakrishnan et al. (1997) detected a significant increase in [3H]cytisine binding upon exposure to nicotine at concentrations as low as 100 nM, and a maximal 15-fold increase in binding at concentrations of 10 μM of nicotine in the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293 that expressed heterologous α4β2 nAChRs (Gopalakrishnan et al., 1997). This is particularly interesting because smokers have an average serum concentration of 100–200 nM nicotine after smoking (Benowitz, 1996, Henningfield et al., 1993), suggesting that nAChR upregulation could occur in smokers in between, as well as during, periods of smoking.

As expected, because at baseline human brains have different levels of nicotine binding in different regions of the brain (Court & Clementi, 1995), the magnitude of increase in nicotine binding sites is not universal among all areas of the brain (Benwell et al., 1988, Perry et al., 1999). Regions of the thalamus appear most resistant to nicotine-induced upregulation of nAChR numbers in rodent models (Kellar et al., 1989, Pauly et al., 1991). In humans, the medulla oblongata, as well as different layers of the cortex and hippocampus are resistant to, or undergo nAChR upregulation at variable rates (Benwell et al., 1988, Perry et al., 1999). Given that nAChR subunits show variable expression in different regions of the brain, this suggests that individual neuronal nicotinic receptor subtypes may undergo differential upregulation according to location in the brain. In addition to upregulation of α4β2 subunit-containing receptors (Flores et al., 1992, Zhang et al., 1995), α3, albeit requiring a higher dose of nicotine, as well as α7, to a lesser extent, subunits are also upregulated (Olale et al., 1997, Peng et al., 1997, Rasmussen & Perry, 2006, Wang et al., 1996). However, not all nAChR subunits undergo nicotine-induced upregulation. For example, it has been reported that α4β2 nAChRs that also contain the α5 subunit (α4β2α5 nAChRs) do not upregulate in response to nicotine treatment (Mao et al., 2008). Autoradiographic studies have demonstrated that chronic nicotine exposure decreases the number of α6-containing receptors (Lai et al., 2005, Marks et al., 2014, Mugnaini et al., 2006, Perry et al., 2007). However, in the presence of β3 subunits this phenomenon is not observed and the α6-containing receptors do not downregulate, suggesting that one role of β3 is to inhibit nicotine-induced downregulation (Perry et al., 2007). Although the typical serum concentration of nicotine in smokers has little effect on muscle nAChRs (Lindstrom, 1996), upregulation of ganglionic α3β4 and α7 subunits, as well as the muscle type nAChR subunits α1, β1, γ, and δ, has been observed on the cell surface after a 48 hour exposure to nicotine at concentrations as low as 1μM (Ke et al., 1998). These findings confirm results from two previous studies on muscle nAChRs (Luther et al., 1989, Siegel & Lukas, 1988). However, earlier studies found that nAChRs in muscle cells are downregulated 40% by chronic exposure to nicotinic agonists (Appel et al., 1981, Gardner & Fambrough, 1979, Noble et al., 1978) at concentrations ranging from 10−3 M to 10 μM (for a review see (Lindstrom, 1996)). Ke et al. (1998) also found that different concentrations of nicotine upregulate different receptor subunits to varying degrees. For example, α3β4 subunits were more prone to upregulation than muscle nAChRs.

Subunit mRNA is unchanged in response to nicotine

Surprisingly, nicotinic receptor subunit mRNA is unchanged in response to nicotine. Early studies by Marks and colleagues showed that while there is an upregulation in α4β2 nAChR binding levels, mRNA for these nAChR subunits as well as for the α2, α3, α5 and β4 subunits remains steady under a nicotine dose of 4 mg/kg/hr (similar to the 5 mg/kg/hr dose originally shown to produce nAChR upregulation in the mouse (Marks et al., 1983)) (Marks et al., 1992). These results were replicated in subsequent studies performed in mouse cell lines (Bencherif et al., 1995, Peng et al., 1994, Zhang et al., 1995), human cell lines (Peng et al., 1997) and rat brain (Bencherif et al., 1995), and are consistent under nicotine concentrations ranging from 10 nM to 5 μM. Ke et al. (1998) expanded the aforementioned work in cultured human cell lines and reported that changes in nAChR numbers are not attributable to changes in CHRNA1, CHRNA3, CHRNA5, CHRNA7, CHRNB2, CHRNB4, CHRND, or CHRNG mRNA levels under exposure to 1 mM nicotine (Ke et al., 1998). It is important to keep in mind that many of the cell lines utilized do not endogenously express nAChRs. Thus, nAChR expression is not controlled by the endogenous regulatory sequences in each cell line, which could confound the results but also clearly demonstrates that native regulatory sequences are not required for upregulation. Although there have been many studies on nAChR subunit mRNA in human brains, these studies have primarily focused on nAChR expression changes in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s Diseases, or in aging brains, and to date only one study was conducted to examine the correlation between nAChR subunit protein and mRNA in smokers. In 2003, Mousavi et al. found that protein levels of the α4 and α7 nAChR subunits were significantly increased in the temporal cortex of smokers compared to those of nonsmokers. As in the rodent and cell line studies, there were no differences in CHRNA4 and CHRNA7 mRNA in the temporal cortex of smokers as compared to those of nonsmokers (Mousavi et al., 2003). Thus, all current evidence strongly indicates that the nicotine-induced upregulation of nAChR numbers is independent of transcriptional events.

Upregulation in development

Maternal smoking presents a large public health concern (Mathews, 2001) and research has indicated prenatal nicotine exposure can lead to altered behavior, potentially through interactions with the nAChRs. Numerous studies have found evidence for nAChR (particularly the α4β2-containing and α7 receptors) upregulation in rodents exposed to nicotine during prenatal (Hagino & Lee, 1985, Navarro et al., 1989, Popke et al., 1997, Slotkin et al., 1987, Tizabi & Perry, 2000, Tizabi et al., 1997, van de Kamp & Collins, 1994), neonatal (Eriksson et al., 2000, Huang & Winzer-Serhan, 2006, Miao et al., 1998) and postnatal (Narayanan et al., 2002, Nunes-Freitas et al., 2011) development. Nicotine exposure in each of these studies differed with each experimental objective. The majority of the studies looking at prenatal nicotine exposure used dosages around 6 or 9 mg/kg/day in rats and 2 mg/kg/hr in mice, which is roughly in agreement with what was used previously. However, Hagino and Lee’s 1985 study used a slightly lower dose of 175 μg/0.9μl/hr in rats with similar findings (Hagino & Lee, 1985). The doses used were much more varied in neonatal mice, yet the results were nevertheless consistent. Postnatal rats were treated with 2, 4, or 6 mg/kg/day nicotine, similar to the dose used by Schwartz and Kellar (Schwartz & Kellar, 1983). One study found evidence for downregulation of α7 receptors in rats after exposure to 9 mg/kg/day nicotine during gestation (Tizabi et al., 2000). Concurrent prenatal and postnatal chronic nicotine administration has also induced receptor upregulation in monkeys (Slotkin et al., 2002). Interestingly, nAChR upregulation during rodent fetal development was more long-lasting than in the adult, implying nicotine has some action beyond immediate receptor upregulation (Slotkin et al., 1987, van de Kamp & Collins, 1994). However, the nicotine doses were slightly different than those used in the first studies showing upregulation; 2 mg/kg/hr verses 5 mg/kg/hr nicotine (Marks et al., 1983) in mice and 6 mg/kg/day verses 4 mg/kg/day (Schwartz & Kellar, 1983) in rats. Despite the fact that nAChR upregulation after nicotine exposure in utero does not persist into adolescence or adulthood, prenatal nicotine exposure may, nonetheless, alter the response to nicotine in adolescence or adulthood in rodents (Abreu-Villaca et al., 2004, Gold et al., 2009, Slotkin et al., 2007). Unlike in adulthood, pups born from dams exposed to 2–4 mg/kg/day nicotine have increased nAChR mRNA expression, particularly that of the α7, α4, and β2 subunits (Frank et al., 2001, Lv et al., 2008, Shacka & Robinson, 1998), as well as the α2 subunit (Lv et al., 2008), immediately after nicotine administration is discontinued. Subsequent work has suggested that adolescent rats exposed to 2 mg/kg/day nicotine during gestation show corresponding decreases in nAChR number, as measured by [125I]-epibatidine, and expression of several nAChR subunit mRNAs (Chen et al., 2005). Neonatal nicotine exposure is more similar to nicotine exposure in adult animals in that no change in mRNA expression of the receptors is seen across a range of nicotine concentrations (Huang & Winzer-Serhan, 2006, Miao et al., 1998). Evidence for both receptor upregulation and subunit mRNA expression has also been seen in primary cultures from prenatal human brain exposed to 10 or 100 μM nicotine (Hellstrom-Lindahl et al., 2001). Using a mouse model, work by Picciotto and colleagues have demonstrated that the effects of nicotine exposure during development on later behaviors are attributable to the neuropharmacological effects of nicotine itself, not the effect of nicotine on maternal behaviors (Heath et al., 2010a). Furthermore, the nAChRs are suggested to mediate this effect. Mice developmentally exposed to nicotine though their drinking water (200 μg/ml nicotine) display hypersensitive passive avoidance behavior in adulthood; this behavior is likely driven by α4β2 and α4β2α5 nAChRs on corticothalamic neurons. Specifically, expression of the β2 and α5 subunits is necessary for this behavior (Heath et al., 2010b). The studies above present clear evidence that nicotine exposure during early development acts on and affects both nAChR receptor number and mRNA expression. Although outside the scope of this review, the effect of prenatal nicotine exposure on the central nervous system has been reviewed at length (Dwyer et al., 2009, Pauly & Slotkin, 2008, Winzer-Serhan, 2008). Collectively, long term and widespread consequences of such exposures have been proposed to play a role in various neurobehavioral and physiological disorders (Abbott & Winzer-Serhan, 2012).

Nicotine also produces various effects on the nAChRs when administered in adolescence. Upregulation of α4β2-containing and α7 receptors has been seen in rats administered 2–6 mg/kg/day nicotine in adolescence and periadolescence (Doura et al., 2008), particularly in the midbrain, hippocampus, and cortex (Abreu-Villaca et al., 2003, Trauth et al., 1999). Transient upregulation of α7 receptors in rats after exposure of 2 or 6 mg/kg/day nicotine has been seen also in the striatum (Slotkin et al., 2004). Compared to adults, adolescent upregulation is more persistent (up to 1 month post-treatment), has been seen at doses of nicotine as low as 0.6 mg/kg/day in rats, (Abreu-Villaca et al., 2003), and is more robust, showing increased binding in the midbrain and striatum compared to adults (Levin et al., 2007). Consistent with studies that treated adult rats with 3 or 6 mg/kg/day nicotine (Mugnaini et al., 2006, Perry et al., 2007), downregulation of α6-containing receptors was observed immediately in adolescent rats after discontinuing chronic nicotine treatment of roughly 3 mg/kg/day (Doura et al., 2008). Finally, similar to prenatal exposure, adolescent rat exposure to 6 mg/kg/day nicotine has been shown to alter the activity of the cholinergic system in adulthood (Slotkin et al., 2008). For example, one study found an increase in the mRNA expression of the α5, α6, and β2 subunits of adult rats that self-administered nicotine (roughly 20 μl of 0.04 mg/kg for 1 hour) during adolescence (Adriani et al., 2003).

Proposed mechanisms of upregulation

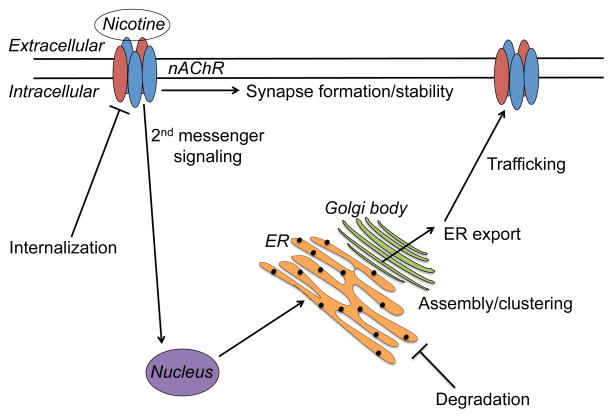

Many studies have been conducted to explore the relation between upregulation of nAChRs and nicotine exposure. Nicotine can pass through the plasma membrane of a cell and has been found in high concentration in cell organelles, as measured in the submaxillary glands of rats by Putney and Borzelleca in 1971 (Putney & Borzelleca, 1971). There are several major models for how nAChR upregulation occurs, some of which are not necessarily mutually exclusive. These include 1) migration from a pool of pre-assembled receptors in the cell, 2) alteration of translation rates via two 2nd messenger pathways, 3) change in stoichiometry of cell surface receptors, 4) increased intracellular assembly of nAChRs in combination with decreased turnover of surface receptors, 5) increased exocytic trafficking of nAChRs to the cell surface, 6) increased subunit maturation and assembly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), possibly through the molecular chaperoning of nAChRs by nicotine, and 7) inhibition of subunit degradation leading to new receptors from recycled subunits (Figure 1). It will be important to determine how these different mechanisms might be integrated during development and possibly modified by exposure to nicotine. It is also important to note that the vast majority of studies examining the mechanism of upregulation have focused on α4β2 nAChRs.

Figure 1.

Cellular processes proposed to play a role in nicotine-induced nAChR upregulation. ER: endoplasmic reticulum.

Early work by Bencherif et al. (1995) suggested that the increase in α4β2 nAChR numbers comes from a pool of assembled receptors within the cell as opposed to altered receptor turnover based on the observation that exposure to 1 μM nicotine had no effect on the degradation of nAChRs in an M10 mouse cell line. They hypothesized that the increase in nicotine binding sites is due a migration of intracellular nAChRs to the surface of the cell and observed that nAChR upregulation had an upward limit of 150%, suggesting the intracellular nAChR reservoir is finite. The authors hypothesized that the intracellular reservoir could exist as a result of several different mechanisms and set the stage for subsequent research (Bencherif et al., 1995).

Another theory is that two 2nd messenger pathways influence nAChR upregulation, possibly through altering translation rates. A series of three in vitro studies by Gopalakrishnan et al. (1997) showed that cells treated with 1 μM nicotine and cyclohexamide, a protein synthesis inhibitor, were resistant to nicotine-induced α4β2 nAChR upregulation, cells treated with 1 μM nicotine and the second messenger analog dibutyl cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) showed enhanced nicotine-induced nAChR upregulation, and cells treated with 1 μM nicotine and protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitors failed to produce nicotine-induced nAChR upregulation. This supports the theory that the nicotine-induced nAChR upregulation could be due to two second messenger pathways, one involving PKC and one involving cAMP, either individually or in conjunction with one another (Gopalakrishnan et al., 1997). A potential role for PKC in α4β2 expression was supported by a study by Nashmi et al. (2003), demonstrating increased trafficking of α4β2 nAChRs to the plasma membrane after the activation of PKC in vitro (Nashmi et al., 2003).

In 2005, Vallejo et al. (2005) proposed that upregulation of α4β2 nAChRs is due to a change in ligand affinity of receptors already present on the cell surface. Using a biotinylation assay they determined that nicotine exposure did not alter the ratio of intracellular to surface receptors. The authors experiments also suggested that nAChR upregulation is independent of intracellular receptor trafficking and concluded that what is termed upregulation is the result of receptors changing from a resting state to an active and high affinity state following chronic nicotine exposure (Vallejo et al., 2005). However, subsequent work has provided evidence contradicting this theory. Marks et al. (2011) showed that mice chronically treated with 1, 2, or 4 mg/kg/hr nicotine show a dose-dependent increase in antibody binding to the α4 and β2 nAChR subunits. This work strongly suggests that nicotine-induced nAChR upregulation reflects increased levels of nAChR protein (Marks et al., 2011) and not a conformational change in existing nAChRs enabling them to bind ligands with higher affinity. It is important to note that these studies had vastly different experimental protocols; Vallejo et al. (2005) used a human cell line with heterologous expression of α4β2 nAChRs exposed to 10 μM nicotine (Vallejo et al., 2005) whereas Marks et al. (2011) exposed mice up to 4 mg/kg/hr nicotine (Marks et al., 2011).

Several studies have provided evidence that upregulation of α4β2 nAChRs is due to mechanisms that increase assembly of intracellular nAChRs and decrease the rate of turnover of surface nAChRs (Kuryatov et al., 2005, Peng et al., 1994, Wang et al., 1998). In a mouse fibroblast cell line, expressing α4 and β2 subunits, exposure of the protein synthesis inhibitor cyclohexamide with 5 μM nicotine showed that (−)-[3H]nicotine binding remained higher compared to control cells for a longer time, indicating that nAChR degradation was prolonged (Peng et al., 1994). This work was replicated with the α3 and β2 subunits at a higher nicotine concentration of 100 μM nicotine in HEK cells, and additionally found a very small increase of β2 subunits within the cell despite the 5 fold increase in α3β2 receptors on the cell surface, suggesting the rate of assembly of the complete nicotinic receptor increases with exposure to nicotine (Wang et al., 1998). Finally, Kuryatov et al (2005) proposed that nicotine binds to the acetylcholine binding site of partially assembled α4β2 nAChRs in the lumen of the ER where a plethora of unassembled nAChR subunits reside. Binding of nicotine to an (α4β2)2 tetramer in the ER would then cause a conformational change that would increase the rate of addition of a 5th subunit to produce a mature nAChR, thus accounting for nicotine-induced nAChR upregulation (Kuryatov et al., 2005).

Another theory is that nAChR upregulation is a consequence of increased nAChR exocytic trafficking to the cell surface. The authors disrupted the secretory pathway with brefeldin A, a compound that disrupts trafficking from the Golgi apparatus, and found that cells exposed to brefeldin A alone show a decrease in nAChR surface numbers and cells exposed to both brefeldin A and nicotine showed no upregulation of surface nAChRs. This result, however, was not seen when the authors measured intracellular nAChRs (Darsow et al., 2005). These results indicated that transport through the secretory pathway is necessary for upregulation of surface nAChRs but there is likely another mechanism responsible for increasing the intracellular concentration of nAChRs. Although a stark contrast to previous findings, this study used a concentration of 500 nM (Darsow et al., 2005), much smaller than the 1–100 μM concentrations of nicotine utilized in the studies described above (Kuryatov et al., 2005, Peng et al., 1994, Wang et al., 1998).

Similar to some of the work described above, several studies have proposed nAChR upregulation is caused by increased subunit maturation and receptor assembly in the ER (Harkness & Millar, 2002, Nashmi et al., 2003, Sallette et al., 2005). Evidence for this theory has come from various studies using transfected α4 and β2 subunits. In one such study, the amount of total β2 subunit protein, but not α4 subunit protein, folded into correct conformation was influenced by both co-assembled partner subunits (the α4 subunit) and by chronic nicotine treatment of 10 μM, suggesting that nAChR upregulation was not due to increase in total protein but how readily the subunits mature and fold in the ER (Harkness & Millar, 2002). Subsequent studies concluded that increased assembly of nAChRs occurs in the soma of neurons after which these nAChRs must be subsequently trafficked to the dendritic processes where there is a larger overall concentration of nAChRs, and that 1 μM nicotine exposure increases the assembly of nAChRs (Nashmi et al., 2003). Additional evidence supporting this theory showed that α4 and β2 subunits undergo complex oligosaccharide glycosylation, a modification known to only occur in the ER and the Golgi apparatus, before they become heteromeric complexes and, furthermore, these glycosylations were found on all pentameric complexes, indicating that the receptor must be completely assembled into a 5-subunit pentameric complex in order to exit the ER and Golgi. Micromolar levels of nicotine exposure were shown to increase the amount of complex oligosaccharides on nAChR subunits (Sallette et al., 2005). In the same vein, a theory has been proposed to account for increased subunit maturation and receptor assembly after nicotine exposure, termed “inside-out pharmacology.” In short, the main posits of this theory are: nicotine and certain other nicotinic ligands enter the ER or Golgi where they bind and stabilize newly forming nAChR pentamers; this “pharmacological chaperoning” of nAChRs by nicotine results in increased trafficking of nAChRs through the secretory pathway; and, once at the plasma membrane, nAChRs remain stabilized by nicotine thus reducing receptor turnover (Henderson & Lester, 2015). In summary, these studies demonstrate several important findings: nAChR subunits undergo maturation and subsequently are assembled into pentamers in the ER of the cell soma and translocated to the cell surface; this process could escalate upon exposure to nanomolar amounts of nicotine; and this phenomenon might in fact be driven by the pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs by nicotine (Harkness & Millar, 2002, Henderson & Lester, 2015, Nashmi et al., 2003, Sallette et al., 2005).

Yet another theory poses that subunit degradation is blocked and subunits are consequently recycled to form new nicotinic receptors (Christianson & Green, 2004, Ficklin et al., 2005, Rezvani et al., 2007). Treatment with proteasomal inhibitors has been shown to increase nAChR numbers and assembly in several cells lines (Christianson & Green, 2004). Ubiquilin-1, a ubiquitin-like protein that can interact with both the proteasome and ubiquitin ligases in protein degradation, co-immunoprecipitated with the α3 subunit and reduced the number of surface nAChRs when transfected into cells. While neurons not exposed to nicotine and injected with a ubiquilin-1 lentivirus showed no changes in α3-containing nAChR levels, nicotine-induced upregulation of α3-containing nAChRs was abated in neurons exposed to 100 μM nicotine after injection with a ubiquilin-1 lentivirus (Ficklin et al., 2005). Another study showed that nicotine itself can act as a partial proteasome inhibitor: in the prefrontal cortex of mice treated with 0.5 mg/kg of nicotine every 6 hours for 1 day, nicotine caused an increase in ubiquitinated proteins, including the α7 subunit suggesting reduced proteosomal activity. This inhibition of proteosomal activity was not due to a decrease in expression of the proteasome, as nicotine was found to increase expression of proteasomal subunits (Rezvani et al., 2007). Subsequent work by the same group focused on UBXN2A, a protein containing an ubiquitin-like domain that binds to ubiquitin. This protein was also observed to bind to and alter to α3 subunit expression: over expression of UBXN2A resulted in an increase in α3β2 nAChRs, and expression of UBXN2A was found to decrease levels of α3 subunit ubiquitination (Rezvani et al., 2009).

While the above studies have supported various theories of nicotine-induced nAChR upregulation, many of them are not mutually exclusive. It is important to note that there are receptor-specific assembly folding factors that fold individual nAChR subunits present in some mammalian cells lines and not others (Sweileh et al., 2000), and different nAChR upregulation mechanisms may be impacted by cell line specific folding factors. Recently, work by Govind et al. (2012) has proposed that nAChR upregulation is not due to a single process as suggested by some of the above studies, but multiple processes occurring at different rates. By measuring the kinetics of upregulation in cells exposed to 10 μM nicotine, the authors surmised that upregulation occurred at two different rates: an initial fast component of upregulation that saturated after 4 hours, during which binding of conformation-dependent antibodies occurred suggesting the fast component of upregulation results from nicotine-induced conformational changes as previously reported (Vallejo et al., 2005); and a slower component that increased with continued nicotine exposure, during which proteasomal inhibition produced even higher levels of subunits in the cell and the authors concluded was due to decreased proteasome-dependent subunit degradation and increased subunit assembly in line with previous work (Harkness & Millar, 2002, Nashmi et al., 2003, Rezvani et al., 2007, Sallette et al., 2005). These results suggest that there are many mechanisms, each acting at a different rate, that contribute to nAChR upregulation (Govind et al., 2012). Although the findings of several of the studies presented above directly contrast those of other studies, it is important to consider differences in nicotine exposure and experimental procedure as possible explanations. It is possible these mechanisms are differentially regulated during different developmental stages, under different conditions of nicotine exposure, and with additional variation contributed by genetic differences (discussed below).

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and human genetic association studies

Drug use phenotypes

There have been numerous associations between the CHRN genes and various drug phenotypes (Table 1), particularly those relating to nicotine. It is worth noting that although other ethnicities have been used and show association with these genes and drug phenotypes, the majority of these associations have been seen in European American (EA) samples. Many of these associations lie within a cluster of genes on chromosome 15q25: CHRNA3, CHRNB4, and CHRNA5. This cluster of genes has been the most consistently replicated association with cigarettes per day (CPD) (Berrettini et al., 2008, Cannon et al., 2014, Caporaso et al., 2009, Furberg et al., 2010, Gabrielsen et al., 2013, Liu et al., 2010, Saccone et al., 2010a, Sarginson et al., 2011, Sorice et al., 2011, Stevens et al., 2008, Thorgeirsson et al., 2010) and nicotine dependence (ND) (Baker et al., 2009, Bierut et al., 2007, Bierut et al., 2008, Broms et al., 2012, Chen et al., 2009, Erlich et al., 2010, Haller et al., 2012, Maes et al., 2011, Saccone et al., 2009a, Saccone et al., 2009b, Sherva et al., 2010, Spitz et al., 2008, Thorgeirsson et al., 2008, Weiss et al., 2008, Wessel et al., 2010), but more recently the genes for other nAChR subunits have been associated with smoking and other drug phenotypes. CHRNB3-A6 on chromosome 8p11 has reached genome-wide significance levels for association with CPD (Thorgeirsson et al., 2010) and ND (Bierut et al., 2007, Culverhouse et al., 2014, Haller et al., 2012, Hoft et al., 2009b, Rice et al., 2012, Saccone et al., 2009a, Saccone et al., 2010b, Saccone et al., 2007, Wang et al., 2014). In addition, evidence for association between common variants in other CHRN genes (CHRND-G, CHRNB1, CHRNA10, CHRNA4, and CHRNB2) and CPD and ND have been reported, although less replicated (Chen et al., 2013, Han et al., 2011, Kamens et al., 2013, Li et al., 2005, Saccone et al., 2009a, Saccone et al., 2010b).

Table 1.

Association of nAChR markers with phenotypes for human drug use.

| Phenotype | Gene(s) | Sample(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NDa | CHRNA4 | Families from Anhui Province, China | (Feng et al., 2004) |

| ADb | CHRNA4 | Unrelated Korean males | (Kim et al., 2004) |

| ND | CHRNA4 | Subjects of European or African ancestry from southern US (TN, MS, or AK) | (Li et al., 2005) |

| Subjective responses to alcohol and tobacco, past 6 month use alcohol | CHRNA4, CHRNB2 | CADDc | (Ehringer et al., 2007) |

| ND | CHRNB3, CHRNA5 | COGENDd | (Bierut et al., 2007, Saccone et al., 2007) |

| Age of initiation of alcohol and tobacco | CHRNA3-B4 | CADD, NYSe | (Schlaepfer et al., 2008) |

| Early subjective response to tobacco | CHRNB3-A6 | CADD, Add Healthf | (Zeiger et al., 2008) |

| CPDg | CHRNA5-A3 | Three European populations | (Berrettini et al., 2008) |

| AD | CHRNA5-A3 | COGAh | (Wang et al., 2009) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3 | >11,000 Icelandic and European samples | (Thorgeirsson et al., 2008) |

| “Pleasurable buzz” during early experimentation with smoking | CHRNA5 | American Caucasians and African Americans | (Sherva et al., 2008) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | COGA | (Bierut et al., 2008) |

| Age-dependent ND | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Three American cohorts | (Weiss et al., 2008) |

| ND | CHRNB3-A6 | NYS | (Hoft et al., 2009b) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3-B4, CHRNB3-A6, CHRND-G | COGEND | (Saccone et al., 2009a) |

| Cocaine dependence | CHRNA5 | FSCDi, COGA | (Grucza et al., 2008) |

| Heavy smoking | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | American Cancer Society CPS-II Cohort, and the CPS-II Nutrition Cohort | (Stevens et al., 2008) |

| Level of response to alcohol | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | San Diego Sibling Pair | (Joslyn et al., 2008) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Two Texas samples | (Spitz et al., 2008) |

| Smoking cessation | CHRNB2 | Pharmacogenetic trial of bupropion for smoking cessation | (Conti et al., 2008) |

| Smoking cessation | CHRNA5, CHRNA2 | Pharmacogenetic trial of bupropion for smoking cessation | (Heitjan et al., 2008) |

| Smoking cessation during pregnancy | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | European pregnant women | (Freathy et al., 2009) |

| CPD | CHRNA5-A3 | Cancer Genetic Markers of Susceptibility | (Caporaso et al., 2009) |

| Alcohol consumption | CHRNB3-A6 | NYS Family Study | (Hoft et al., 2009a) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Utah and Wisconsin cohorts | (Baker et al., 2009) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | African Americans subjects from COGEND | (Saccone et al., 2009b) |

| ND, AD | CHRNA5-A3 | Virginia Adult Twin Study | (Chen et al., 2009) |

| Heavy alcohol use | CHRNA6 | Spanish population | (Landgren et al., 2009) |

| CPD | CHRNA3 | Tobacco and Genetics Consortium, ENGAGEj, Ox-GSKk | (Furberg et al., 2010) |

| ND | CHRNB3-A6, CHRNA4, CHRNB1, CHRNA10, CHRND-G | COGEND | (Saccone et al., 2010b) |

| CPD | CHRNA5-A3-B4, CHRNB3-A6 | ENGAGE | (Thorgeirsson et al., 2010) |

| ND in treatment-seeking smokers | Neuronal CHRN genes | Group Health | (Wessel et al., 2010) |

| Smoking initiation, smoking cessation | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Korean subjects | (Li et al., 2010) |

| Dizziness to tobacco | CHRNB3, CHRNA10 | COGEND | (Ehringer et al., 2010) |

| Smoking quantity | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Os-GSK | (Liu et al., 2010) |

| Smoking quantity | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | CGASP l | (Saccone et al., 2010a) |

| ND, cocaine dependence, AD | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Five American cohorts (Uconn, Yale, MUSC, UPENN, McLean) | (Sherva et al., 2010) |

| Opioid dependence severity, ND severity | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Outpatients in treatment for opioid dependence | (Erlich et al., 2010) |

| Heavy smoking | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Three German Cohorts (KORA, NCOOP, ESTHER) | (Winterer et al., 2010) |

| ND | CHRNA5 | Yale University Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center | (Lori et al., 2011) |

| Subjective response to nicotine | CHRNB2 | Daily smokers from the Denver/Boulder area | (Hoft et al., 2011) |

| Smoking quantity, response to smoking cessation therapy | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Two studies, MT1 and MT2 | (Sarginson et al., 2011) |

| CPD, ND | CHRNA4 | Five American cohorts (Uconn, Yale, MUSC, UPENN, McLean) | (Han et al., 2011) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3 | Virginia Twin Registry | (Maes et al., 2011) |

| Smoking quantity | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Three Italian populations | (Sorice et al., 2011) |

| ND | CHRNA4 | Five American cohorts (Uconn, Yale, MUSC, UPENN, McLean) | (Xie et al., 2011) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3-B4, CHRNB3-A6 | COGEND | (Haller et al., 2012) |

| ND, CPD | CHRNB3 | SAGEm | (Rice et al., 2012) |

| ND, regular drinking | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Finnish Twin Cohort | (Broms et al., 2012) |

| Objective measures of tobacco exposure | CHRNA5-A3 | Six European studies | (Munafo et al., 2012) |

| Onset of habitual smoking | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | COGA | (Kapoor et al., 2012) |

| Genetic vulnerability to smoking in early-onset smokers | CHRNA5 | Meta-Analysis | (Hartz et al., 2012) |

| Smoking quantity | CHRNA5-A3 | STOMPn Genetics Consortium | (David et al., 2012) |

| General substance use initiation | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Add Health | (Lubke et al., 2012) |

| Pack years of smoking | CHRNA5-A3 | Chinese Han population of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients | (Zhou et al., 2012) |

| ND | CHRNA5-A3-B4, CHRNB3-A6 | COGEND | (Chen et al., 2012a) |

| CPD, age of smoking cessation, response to pharmacologic therapy | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities, University of Wisconsin Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center | (Chen et al., 2012b) |

| ND | CHRNA4, CHRNB2 | Japanese | (Chen et al., 2013) |

| ND | CHRNA4, CHRNB2 | CADD, GADDo | (Kamens et al., 2013) |

| Alcohol use | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | National FINRISK Study, Health 2000 Survey | (Hallfors et al., 2013) |

| Response to smoking cessation therapies | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Eight clinical trials for smoking cessation | (Bergen et al., 2013) |

| Smoking quantity, snus consumption | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Nord-Trøndelag Health Study | (Gabrielsen et al., 2013) |

| ND | CHRNB3 | Subjects of European, African, and Asian ancestry from MSTCCp, SAGE, CGEMSq, and KAREr studies | (Cui et al., 2013) |

| Nicotine intake | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Alaskan natives | (Zhu et al., 2013) |

| Onset of regular smoking | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Meta-Analysis | (Stephens et al., 2013) |

| Cocaine use disorder | CHRNB3 | SAGE | (Sadler et al., 2014) |

| CPD | CHRNA5-A3-B4, CHRNB3-A6, CHRNA2 | SECASPs | (Cannon et al., 2014) |

| Frequency of binge drinking | CHRNA4 | SECASP | (Coon et al., 2014) |

| ND | CHRNA2, CHRNA6 | European and African Americans from TN, AR, MI, and MS; SAGE | (Wang et al., 2014) |

| CPD | CHRNB4 | COGEND | (Haller et al., 2014b) |

| Opioid dependence and withdrawal | CHRNA3 | SAGE | (Muldoon et al., 2014) |

| Dizziness at smoking initiation | CHRNA3, CHRNA4, CHRNA6, CHRNA7 | Nicotine Dependence in Teens | (Pedneault et al., 2014) |

| Smoking cessation | CHRNA5-A3-B4 | Two smoking cessation trials in African Americans: the Nicotine Gum Study, and Bupropion Study | (Zhu et al., 2014) |

| Use of smokeless tobacco | CHRNA5-A3 | Two studies conducted in India: the International multicenter oral cancer study, and the Mumbai study | (Anantharaman et al., 2014) |

| Severe withdrawal in a subgroup of smokers with higher lifetime prevalence of depression | CHRNA4 | Treatment-seeking smokers from 5 Hungarian cessation centers | (Lazary et al., 2014) |

| COPD, lung cancer, heavy smoking (pack years) | CHRNA7 | Southern and eastern Han Chinese population | (Yang et al., 2015) |

| AD and cocaine dependence | CHRNA3, CHRNB3 | COGA | (Haller et al., 2014a) |

| ND | CHRNB3-A6 | COGA, COGEND, FSCD | (Culverhouse et al., 2014) |

| CPD | CHRNA5, CHRNB4, CHRNA6 | Virginia Twin Study on Adolescent and Behavioral Development | (Clark et al., 2015) |

| ND | CHRNA5 | Meta-analysis | (Olfson et al., 2015) |

ND: Nicotine Dependence

AD: Alcohol Dependence

CADD: Center on Antisocial Drug Dependence

COGEND: Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Nicotine Dependence

NYS: National Youth Survey

Add Health: National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health

CPD: Cigarettes per Day

COGA: Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism

FSCD: Family Study of Cocaine Dependence

ENGAGE: European Network of Genomic and Genetic Epidemiology

Ox-GSK: Oxford-GlaxoSmithKline

CGASP: Consortium for the Genetic Analysis of Smoking Phenotypes

SAGE: Study of Addiction: Genetics and Environment

STOMP: Study of Tobacco in Minority Populations

GADD: Genetics of Antisocial Drug Dependence

MSTCC: Mid-South Tobacco Case Control Study

CGEMS: Genome Wide Scan of Lung Cancer and Smoking

KARE: Korea Association Resource study

SECASP: Social and Emotional Contexts of Adolescent Smoking Patterns

Work by Saccone and colleagues have confirmed at least three independent genetic signals in the 15q25 cluster (Saccone et al., 2010a). Twin studies have estimated that ND and CPD are roughly 56–72% and 51–61% heritable in men and women, respectively (Broms et al., 2006, Kendler et al., 1999, Lessov et al., 2004, True et al., 1999b, Vink et al., 2004); however, the most well-replicated of these associations accounts for a very small proportion of the variance in smoking (roughly 1 cigarette per day) (Berrettini & Doyle, 2012, Saccone et al., 2010b). This single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), rs16969968 (a nonsynonymous SNP residing in CHRNA5, also often tagged by rs1051730), has been consistently associated with ND and smoking behavior (Baker et al., 2009, Berrettini et al., 2008, Bierut et al., 2007, Chen et al., 2012a, Chen et al., 2009, Furberg et al., 2010, Hartz et al., 2012, Liu et al., 2010, Saccone et al., 2010a, Saccone et al., 2007, Sherva et al., 2010, Stevens et al., 2008, Thorgeirsson et al., 2008, Thorgeirsson et al., 2010, Weiss et al., 2008, Winterer et al., 2010). This signal has also been associated with alcohol dependence (AD) (Wang et al., 2009), cocaine dependence (CD) (Grucza et al., 2008, Sherva et al., 2010), opioid dependence (Sherva et al., 2010), and opioid dependence severity (Erlich et al., 2010). Interestingly, studies in EAs have shown that the rs16969968 risk allele for ND is a protective allele for AD (Chen et al., 2009) and CD (Grucza et al., 2008). Furthermore, the finding with CD has been replicated in another EA sample, as well as an African American sample (Sherva et al., 2010). Although the biological mechanisms for the bi-directional effect are unknown, one explanation might be due to the contribution of nAChRs to both excitatory and inhibitory effects on dopaminergic reward pathways (Grucza et al., 2008).

Many of these genes have been associated also with alcohol use. CHRNA5-A3-B4 has been associated with AD (Chen et al., 2009, Sherva et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2009), alcohol use (Broms et al., 2012, Hallfors et al., 2013), age of initiation of alcohol use (Schlaepfer et al., 2008), and level of response to alcohol (Joslyn et al., 2008). CHRNB3-A6 have been associated with alcohol consumption (Hoft et al., 2009a) and heavy alcohol use (Landgren et al., 2009). Finally, CHRNA4 has been associated with AD (Kim et al., 2004) and frequency of binge drinking (Coon et al., 2014). Both CHRNA4 and CHRNB2 have been associated with subjective response to alcohol (Ehringer et al., 2007).

More recently, several groups have used Next Generation sequencing approaches to comprehensively assess the coding regions of CHRN genes. In particular, past evidence for common variant associations in CHRNA4 have been limited. However, sequencing studies have revealed this gene has been technically more challenging to sequence, suggesting there may be genomic features in this region that have impeded traditional SNP assays. In a sample of EAs participating in a smoking cessation trial, Wessel et al. (2010) found evidence for association with ND between common and rare variants in CHRNA5 and CHRNB2, and for rare variants in CHRNA4 (Wessel et al., 2010). At the time, the research team was able to sequence the other CHRN genes using 454 technology, but needed to use Sanger sequencing for CHRNB2 and CHRNA4. In 2011, Xie et al. reported a protective effect of rare alleles in CHRNA4 for ND in a small EA sample (Xie et al., 2011). Some of these variants were shown to lead to significant differences in nAChR expression, subcellular distribution, and sensitivity to nicotine-induced receptor upregulation in HEK 293 cells and Xenopus laevis oocyte studies (Mcclure-Begley et al., 2014). In addition, rare variants in CHRNB4 have been associated with ND (Haller et al., 2012), and rare variants in CHRNB3 and CHRNA3 have been associated with AD and CD (Haller et al., 2014a). More recently, rare variants in CHRNA5 and CHRNB4 (but not CHRNA3) were associated with CPD in an EA sample, as was CHRNA6 (but not CHRNB3) (Clark et al., 2015). Finally, evidence for rare variant associations in both EA and African American samples in the CHRNA5 gene were reported for ND (Olfson et al., 2015). Collectively, the emerging data from rare variant studies suggests there are many different ways in which genetic variation in the CHRN genes may lead to risk for increased smoking. It will be important to draw on these databases of naturally occurring rare variants to perform follow-up functional molecular work and complementary animal studies in order to understand the molecular and pharmacological mechanisms for different kinds of variants.

In addition, recent pharmacogenetic studies have demonstrated that risk haplotype at CHRNA5-A3-B4 is highly predictive of a person’s response to treatment with Varenicline (a nAChR agonist) (Bergen et al., 2013, Chen & Bierut, 2013). To put this in terms of number needed to treat (NNT) for one person to successfully quit smoking, the NNT is 4 among individuals who carry the risk haplotype in the region, whereas among those with the low-risk haplotype the NNT >1000. Thus the collective work of many who have studied the human CHRN genes over the last 10 years is beginning to bear fruit with regard to potential future clinical application.

Age-related effects

Although rs16969968 has been robustly associated with ND and CPD as described above, recent research has indicated that this signal is not associated with age of onset of regular smoking or age of smoking initiation (Furberg et al., 2010, Hartz et al., 2012, Stephens et al., 2013). While two studies, including a large-scale meta-analysis, have found that age of onset of smoking modifies the association between rs16969968 and smoking severity in that that the risk allele for rs16969968 is associated with severity of heavy smoking and ND in smokers who began smoking before age 16 (Hartz et al., 2012, Weiss et al., 2008), research has primarily shown no association between rs16969968 and age of onset of smoking (Hartz et al., 2012, Stephens et al., 2013) and age of initiation of smoking (Furberg et al., 2010, Stephens et al., 2013, Thorgeirsson et al., 2010).

A recent meta-analysis examined two signals independent of rs16969968 (rs578776 and rs1948/rs684513) and found evidence for association with age of onset of smoking but not age of initiation of smoking (Stephens et al., 2013). Although this did not replicate previous associations with rs1948 and rs684513 and early age of tobacco initiation in two samples (Schlaepfer et al., 2008), it is in agreement with two previous genome-wide association studies (Furberg et al., 2010, Thorgeirsson et al., 2010) and one candidate gene study (Winterer et al., 2010) in finding no association with age of smoking initiation. Previous associations have been identified between rs684513 and age of onset of smoking (Broms et al., 2012), heavy smoking (Winterer et al., 2010), and ND (Broms et al., 2012, Lori et al., 2011), and between rs1948 and the tolerance factor of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (Broms et al., 2012). In the meta-analysis by Stephens and colleagues in 2013 rs578776 had the strongest association with age of onset of smoking (Stephens et al., 2013), replicating previous work (Broms et al., 2012). This SNP has previously been associated with ND (Broms et al., 2012, Saccone et al., 2010a, Saccone et al., 2009a, Saccone et al., 2009b, Weiss et al., 2008) and heavy smoking (Stevens et al., 2008). Although the evidence for signals in the CHRN gene cluster on chromosome 15q25 remains mixed for association with age of initiation, studies suggest that some of the signals in the cluster that affect onset of smoking may be different from those affecting dependence and heavy smoking.

Conclusion

Chronic exposure by an agonist induces an upregulation of nAChRs that is not due to increased gene expression in adults. Numerous mechanisms have been proposed to be responsible for this phenomenon: increased nAChR subunit maturation and folding, increased receptor trafficking, and decreased subunit degradation, possibly through the pharmacological chaperoning of nAChRs by nicotine; and increased translation and 2nd messenger signaling. While upregulation also occurs during prenatal, neonatal, and postnatal developmental periods, as well as adolescence, there have been conflicting results regarding a change in corresponding gene expression. However, there is strong evidence that nicotine exposure during these influential periods of development contributes to later changes in the cholinergic system. Results from human genetics studies have provided also strong indication that variation with the CHRN genes is associated with SUDs. Most of the human genetic studies on the nAChRs however have focused on specific associations with nicotine behaviors and have shown several well-replicated signals that are associated with smoking quantity and ND. However, recent work has demonstrated that the most well-replicated of these associations with smoking levels and ND is not associated with age of smoking initiation or age of regular smoking. These differences highlight the overall complexity of molecular genetics in context of similarly heterogeneous phenotypes. As human geneticists continue to search for genes associated with drug behaviors, it is clear that careful attention to the phenotype, and developmental stage of subjects, will be an important consideration for obtaining a global view of how genetics influence behavior over the life-course. Although this review has focused on the nAChRs, other genes are likely to contribute at unique stages of development in concert with nicotine and other drug exposures to modify risk for SUDs.

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by grants DA017637 (J.K.H) and DA036673 (J.A.S.) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and AA017889 (M.A.H.) and AA013525 (E.P.R.) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Abbott LC, Winzer-Serhan UH. Smoking during pregnancy: lessons learned from epidemiological studies and experimental studies using animal models. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2012;42:279–303. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2012.658506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abreu-Villaca Y, Seidler FJ, Qiao D, Tate CA, Cousins MM, Thillai I, Slotkin TA. Short-term adolescent nicotine exposure has immediate and persistent effects on cholinergic systems: critical periods, patterns of exposure, dose thresholds. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1935–1949. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abreu-Villaca Y, Seidler FJ, Tate CA, Cousins MM, Slotkin TA. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters the response to nicotine administration in adolescence: effects on cholinergic systems during exposure and withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:879–890. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriani W, Spijker S, Deroche-Gamonet V, Laviola G, Le Moal M, Smit AB, Piazza PV. Evidence for enhanced neurobehavioral vulnerability to nicotine during periadolescence in rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4712–4716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04712.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Are there genetic influences on addiction: evidence from family, adoption and twin studies. Addiction. 2008;103:1069–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Cannabis and other illicit drugs: comorbid use and abuse/dependence in males and females. Behav Genet. 2004;34:217–228. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000017868.07829.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand R, Conroy WG, Schoepfer R, Whiting P, Lindstrom J. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes have a pentameric quaternary structure. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11192–11198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaman D, Chabrier A, Gaborieau V, Franceschi S, Herrero R, Rajkumar T, Samant T, Mahimkar MB, Brennan P, McKay JD. Genetic variants in nicotine addiction and alcohol metabolism genes, oral cancer risk and the propensity to smoke and drink alcohol: a replication study in India. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel SH, Blosser JC, McManaman JL, Ashizawa T, Elias SB. The effects of carbamylcholine, calcium, and cyclic nucleotides on acetylcholine receptor synthesis in cultured myotubes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1981;377:189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb33732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Weiss RB, Bolt D, von Niederhausern A, Fiore MC, Dunn DM, Piper ME, Matsunami N, Smith SS, Coon H, McMahon WM, Scholand MB, Singh N, Hoidal JR, Kim SY, Leppert MF, Cannon DS. Human neuronal acetylcholine receptor A5-A3-B4 haplotypes are associated with multiple nicotine dependence phenotypes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:785–796. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencherif M, Fowler K, Lukas RJ, Lippiello PM. Mechanisms of up-regulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in clonal cell lines and primary cultures of fetal rat brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:987–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:597–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benwell ME, Balfour DJ, Anderson JM. Evidence that tobacco smoking increases the density of (−)-[3H]nicotine binding sites in human brain. J Neurochem. 1988;50:1243–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb10600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen AW, Javitz HS, Krasnow R, Nishita D, Michel M, Conti DV, Liu J, Lee W, Edlund CK, Hall S, Kwok PY, Benowitz NL, Baker TB, Tyndale RF, Lerman C, Swan GE. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor variation and response to smoking cessation therapies. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2013;23:94–103. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835cdabd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini W, Yuan X, Tozzi F, Song K, Francks C, Chilcoat H, Waterworth D, Muglia P, Mooser V. Alpha-5/alpha-3 nicotinic receptor subunit alleles increase risk for heavy smoking. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:368–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini WH, Doyle GA. The CHRNA5-A3-B4 gene cluster in nicotine addiction. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:856–866. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Dinwiddie SH, Begleiter H, Crowe RR, Hesselbrock V, Nurnberger JI, Jr, Porjesz B, Schuckit MA, Reich T. Familial transmission of substance dependence: alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and habitual smoking: a report from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:982–988. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Madden PA, Breslau N, Johnson EO, Hatsukami D, Pomerleau OF, Swan GE, Rutter J, Bertelsen S, Fox L, Fugman D, Goate AM, Hinrichs AL, Konvicka K, Martin NG, Montgomery GW, Saccone NL, Saccone SF, Wang JC, Chase GA, Rice JP, Ballinger DG. Novel genes identified in a high-density genome wide association study for nicotine dependence. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:24–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut LJ, Stitzel JA, Wang JC, Hinrichs AL, Grucza RA, Xuei X, Saccone NL, Saccone SF, Bertelsen S, Fox L, Horton WJ, Breslau N, Budde J, Cloninger CR, Dick DM, Foroud T, Hatsukami D, Hesselbrock V, Johnson EO, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Madden PA, Mayo K, Nurnberger J, Jr, Pomerleau O, Porjesz B, Reyes O, Schuckit M, Swan G, Tischfield JA, Edenberg HJ, Rice JP, Goate AM. Variants in nicotinic receptors and risk for nicotine dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1163–1171. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter J, Connolly J, Deneris E, Goldman D, Heinemann S, Patrick J. Functional expression of two neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors from cDNA clones identifies a gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7763–7767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese CR, Marks MJ, Logel J, Adams CE, Sullivan B, Collins AC, Leonard S. Effect of smoking history on [3H]nicotine binding in human postmortem brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britto LR, Keyser KT, Lindstrom JM, Karten HJ. Immunohistochemical localization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in the mesencephalon and diencephalon of the chick (Gallus gallus) J Comp Neurol. 1992;317:325–340. doi: 10.1002/cne.903170402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broms U, Silventoinen K, Madden PA, Heath AC, Kaprio J. Genetic architecture of smoking behavior: a study of Finnish adult twins. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:64–72. doi: 10.1375/183242706776403046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broms U, Wedenoja J, Largeau MR, Korhonen T, Pitkaniemi J, Keskitalo-Vuokko K, Happola A, Heikkila KH, Heikkila K, Ripatti S, Sarin AP, Salminen O, Paunio T, Pergadia ML, Madden PA, Kaprio J, Loukola A. Analysis of detailed phenotype profiles reveals CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4 gene cluster association with several nicotine dependence traits. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:720–733. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon DS, Mermelstein RJ, Hedeker D, Coon H, Cook EH, McMahon WM, Hamil C, Dunn D, Weiss RB. Effect of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes (CHRN) on longitudinal cigarettes per day in adolescents and young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:137–144. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso N, Gu F, Chatterjee N, Sheng-Chih J, Yu K, Yeager M, Chen C, Jacobs K, Wheeler W, Landi MT, Ziegler RG, Hunter DJ, Chanock S, Hankinson S, Kraft P, Bergen AW. Genome-wide and candidate gene association study of cigarette smoking behaviors. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking and Tobacco Use—Fact Sheet: Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking. Updated January 2008. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/index.htm.

- CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use: Targeting the Nation’s Leading Killer—At a Glance. 2009 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/pdf/tobacco.pdf.

- Changeux JP. Nicotine addiction and nicotinic receptors: lessons from genetically modified mice. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:389–401. doi: 10.1038/nrn2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Parker SL, Matta SG, Sharp BM. Gestational nicotine exposure reduces nicotinic cholinergic receptor (nAChR) expression in dopaminergic brain regions of adolescent rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:380–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HI, Shinkai T, Utsunomiya K, Yamada K, Sakata S, Fukunaka Y, Hwang R, De Luca V, Ohmori O, Kennedy JL, Chuang HY, Nakamura J. Possible association of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene (CHRNA4 and CHRNB2) polymorphisms with nicotine dependence in Japanese males: an exploratory study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2013;46:77–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1323678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LS, Baker TB, Grucza R, Wang JC, Johnson EO, Breslau N, Hatsukami D, Smith SS, Saccone N, Saccone S, Rice JP, Goate AM, Bierut LJ. Dissection of the phenotypic and genotypic associations with nicotinic dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012a;14:425–433. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LS, Baker TB, Piper ME, Breslau N, Cannon DS, Doheny KF, Gogarten SM, Johnson EO, Saccone NL, Wang JC, Weiss RB, Goate AM, Bierut LJ. Interplay of genetic risk factors (CHRNA5-CHRNA3-CHRNB4) and cessation treatments in smoking cessation success. Am J Psychiatry. 2012b;169:735–742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11101545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LS, Bierut LJ. Genomics and personalized medicine: and smoking cessation treatment. J Food Drug Anal. 2013;21:S87–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2013.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Chen J, Williamson VS, An SS, Hettema JM, Aggen SH, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Variants in nicotinic acetylcholine receptors alpha5 and alpha3 increase risks to nicotine dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:926–933. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JC, Green WN. Regulation of nicotinic receptor expression by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Embo J. 2004;23:4156–4165. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, McClay JL, Adkins DE, Aberg KA, Kumar G, Nerella S, Xie L, Collins AL, Crowley JJ, Quakenbush CR, Hillard CE, Gao G, Shabalin AA, Peterson RE, Copeland WE, Silberg JL, Maes H, Sullivan PF, Costello EJ, van den Oord EJ. Deep Sequencing of Three Loci Implicated in Large-Scale Genome-Wide Association Study Smokig Meta-Analyses. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PB. Nicotine and smoking: a perspective from animal studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;92:135–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00177905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AC, Romm E, Wehner JM. Dissociation of the apparent relationship between nicotine tolerance and up-regulation of nicotinic receptors. Brain Res Bull. 1990;25:373–379. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90222-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti DV, Lee W, Li D, Liu J, Van Den Berg D, Thomas PD, Bergen AW, Swan GE, Tyndale RF, Benowitz NL, Lerman C. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta2 subunit gene implicated in a systems-based candidate gene study of smoking cessation. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2834–2848. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon H, Piasecki TM, Cook EH, Dunn D, Mermelstein RJ, Weiss RB, Cannon DS. Association of the CHRNA4 neuronal nicotinic receptor subunit gene with frequency of binge drinking in young adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:930–937. doi: 10.1111/acer.12319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court J, Clementi F. Distribution of nicotinic subtypes in human brain. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995;9(Suppl 2):6–14. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199501002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier S, Bertrand D, Matter JM, Hernandez MC, Bertrand S, Millar N, Valera S, Barkas T, Ballivet M. A neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit (alpha 7) is developmentally regulated and forms a homo-oligomeric channel blocked by alpha-BTX. Neuron. 1990;5:847–856. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90344-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creese I, Sibley DR. Receptor adaptations to centrally acting drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1981;21:357–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.21.040181.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui WY, Wang S, Yang J, Yi SG, Yoon D, Kim YJ, Payne TJ, Ma JZ, Park T, Li MD. Significant association of CHRNB3 variants with nicotine dependence in multiple ethnic populations. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:1149–1151. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culverhouse RC, Johnson EO, Breslau N, Hatsukami DK, Sadler B, Brooks AI, Hesselbrock VM, Schuckit MA, Tischfield JA, Goate AM, Saccone NL, Bierut LJ. Multiple distinct CHRNB3-A6 variants are genetic risk factors for nicotine dependence in African Americans and European Americans. Addiction. 2014;109:814–822. doi: 10.1111/add.12478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darsow T, Booker TK, Pina-Crespo JC, Heinemann SF. Exocytic trafficking is required for nicotine-induced up-regulation of alpha 4 beta 2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18311–18320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David SP, Hamidovic A, Chen GK, Bergen AW, Wessel J, Kasberger JL, Brown WM, Petruzella S, Thacker EL, Kim Y, Nalls MA, Tranah GJ, Sung YJ, Ambrosone CB, Arnett D, Bandera EV, Becker DM, Becker L, Berndt SI, Bernstein L, Blot WJ, Broeckel U, Buxbaum SG, Caporaso N, Casey G, Chanock SJ, Deming SL, Diver WR, Eaton CB, Evans DS, Evans MK, Fornage M, Franceschini N, Harris TB, Henderson BE, Hernandez DG, Hitsman B, Hu JJ, Hunt SC, Ingles SA, John EM, Kittles R, Kolb S, Kolonel LN, Le Marchand L, Liu Y, Lohman KK, McKnight B, Millikan RC, Murphy A, Neslund-Dudas C, Nyante S, Press M, Psaty BM, Rao DC, Redline S, Rodriguez-Gil JL, Rybicki BA, Signorello LB, Singleton AB, Smoller J, Snively B, Spring B, Stanford JL, Strom SS, Swan GE, Taylor KD, Thun MJ, Wilson AF, Witte JS, Yamamura Y, Yanek LR, Yu K, Zheng W, Ziegler RG, Zonderman AB, Jorgenson E, Haiman CA, Furberg H. Genome-wide meta-analyses of smoking behaviors in African Americans. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e119. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneris ES, Connolly J, Boulter J, Wada E, Wada K, Swanson LW, Patrick J, Heinemann S. Primary structure and expression of beta 2: a novel subunit of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron. 1988;1:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doura MB, Gold AB, Keller AB, Perry DC. Adult and periadolescent rats differ in expression of nicotinic cholinergic receptor subtypes and in the response of these subtypes to chronic nicotine exposure. Brain Res. 2008;1215:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvoisin RM, Deneris ES, Patrick J, Heinemann S. The functional diversity of the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors is increased by a novel subunit: beta 4. Neuron. 1989;3:487–496. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM. The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer MA, Clegg HV, Collins AC, Corley RP, Crowley T, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ, Krauter K, Lessem J, Rhee SH, Schlaepfer I, Smolen A, Stallings MC, Young SE, Zeiger JS. Association of the neuronal nicotinic receptor beta2 subunit gene (CHRNB2) with subjective responses to alcohol and nicotine. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:596–604. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer MA, McQueen MB, Hoft NR, Saccone NL, Stitzel JA, Wang JC, Bierut LJ. Association of CHRN genes with “dizziness” to tobacco. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B:600–609. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgoyhen AB, Johnson DS, Boulter J, Vetter DE, Heinemann S. Alpha 9: an acetylcholine receptor with novel pharmacological properties expressed in rat cochlear hair cells. Cell. 1994;79:705–715. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgoyhen AB, Vetter DE, Katz E, Rothlin CV, Heinemann SF, Boulter J. alpha10: a determinant of nicotinic cholinergic receptor function in mammalian vestibular and cochlear mechanosensory hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3501–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051622798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson P, Ankarberg E, Fredriksson A. Exposure to nicotine during a defined period in neonatal life induces permanent changes in brain nicotinic receptors and in behaviour of adult mice. Brain Res. 2000;853:41–48. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]