Abstract

Research on the emotional, cognitive, and social determinants of moral judgment has surged in recent years. The development of moral foundations theory (MFT) has played an important role, demonstrating the breadth of morality. Moral psychology has responded by investigating how different domains of moral judgment are shaped by a variety of psychological factors. Yet, the discipline lacks a validated set of moral violations that span the moral domain, creating a barrier to investigating influences on judgment and how their neural bases might vary across the moral domain. In this paper, we aim to fill this gap by developing and validating a large set of moral foundations vignettes (MFVs). Each vignette depicts a behavior violating a particular moral foundation and not others. The vignettes are controlled on many dimensions including syntactic structure and complexity making them suitable for neuroimaging research. We demonstrate the validity of our vignettes by examining respondents’ classifications of moral violations, conducting exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, and demonstrating the correspondence between the extracted factors and existing measures of the moral foundations. We expect that the MFVs will be beneficial for a wide variety of behavioral and neuroimaging investigations of moral cognition.

Keywords: Moral judgment, Moral foundations theory, Vignettes, Violations, Intuition

Moral psychology has experienced a “renaissance” in recent years, generating a large empirical literature emphasizing the intuitive and emotional aspects of moral judgment (Greene, 2011). The social intuitionism model (Haidt, 2001) and moral foundations theory (Haidt & Joseph, 2004) have been particularly influential in this burgeoning field. According to the social intuitionism model, moral judgment is an intuitive process, characterized by automatic, affective reactions to stimuli. Moral foundations theory builds on this model, categorizing our moral intuitions into “foundations.” Each foundation represents a set of intuitions that have evolved to solve certain social dilemmas. The current and most widely accepted draft of the theory posits five foundations, though proponents argue there are likely more (Graham, Haidt, Koleva, Motyl, Iyer, Wojcik, & Ditto, 2013). These foundations concern dislike for the suffering of others (Care/harm), proportional fairness (Fairness/cheating), group loyalty (Loyalty/betrayal), deference to authority and tradition (Authority/subversion), and concerns with purity and contamination (Sanctity/degradation). Researchers have recently proposed a sixth foundation (Liberty/oppression), focusing on concerns about domination and coercion (Haidt, 2013; Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto, & Haidt, 2012).

Moral foundations theory has had a large impact in psychology and a variety of other disciplines (for a review, see Graham et al. 2013). Researchers have begun integrating moral foundations theory with research on personality (Hirsh, DeYoung, Xiaowen Xu, & Peterson, 2010; Lewis & Bates, 2011), psychological dispositions (Federico, Weber, Ergun, & Hunt, 2013), and life narratives (McAdams, Albaugh, Farber, Daniels, Logan, & Olson, 2008). In political science, MFT has been used to explain political attitudes and ideology (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009; Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto, & Haidt, 2012; Weber & Federico, 2013; Kertzer et al., 2014), to classify moral rhetoric (Clifford & Jerit, 2013; Sagi & Dehghani, 2013), and to understand how the public evaluates politicians’ character (Clifford, 2014).

Cognitive neuroscientists have also investigated the neurological basis of moral judgment using neuroimaging techniques including functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Early studies compared the neural correlates of moral judgment by comparing evaluations of scenarios with or without moral content (Moll, Eslinger, & Oliveira-Souza, 2001; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Bramati, & Grafman, 2002; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002). More recent studies have examined moral violations of bodily harm (Heekeren, Wartenburger, Schmidt, Prehn, Schwintowski, & Villringer, 2005), different aspects of purity violations such as incest, iniquity, and infection (Schaich Borg, Lieberman, & Kiehl, 2008), and compared harm with purity violations (Parkinson et al., 2011). Others have even begun to explore the relationship between regional brain volumes and responses to the moral foundations questionnaire (Lewis, Kanai, Bates, & Rees, 2012). Although existing research has found differences in the brain regions evoked between moral domains, to our knowledge, no neuroimaging study has examined the full spectrum of morality as depicted by moral foundations theory.

Scholars conducting research relying on moral foundations theory have developed two widely used measures – the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ) and the Sacredness Scale (MFSS). The MFQ measures endorsement of abstract moral principles and self-theories, while the MFSS measures one’s willingness to perform moral transgressions for money. Yet, the literature lacks a validated and comprehensive stimulus set consisting of vignettes designed to elicit moral judgment. Given the dramatic growth of research on moral judgment, the absence of a judgment scale that captures the full breadth of morality represents a substantial impediment to testing and developing theories of morality.

In this article, we introduce and validate the Moral Foundations Vignettes (MFVs). The MFVs consist of 132 scenarios, each of which is a short description of a behavior that violates a particular moral foundation. The MFVs provide a standardized set of scenarios that allows researchers across various disciplines to test a wide variety of theories about the nature of moral judgment. In Study 1, we show that respondents are able to correctly classify which moral foundation is being violated in each scenario. Additionally, we minimized differences between the foundations on a variety of parameters to ensure that subsequent findings could not simply be explained by differences in scenario structure or complexity. These stimulus restrictions should make the MFV particularly useful to researchers in the cognitive neuroscience community. In Study 2, we demonstrate the correspondence of the vignettes to existing moral foundations scales, and investigate the factor structure of our scenarios. Our results demonstrate that the vignettes tap into the intended foundations and correspond with existing measures, but promise to offer new insight into moral judgment.

Limitations of existing moral foundations stimuli

Existing research relies primarily on the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ), which consists of two sections. The relevance section of the MFQ asks respondents to rate the relevance of 15 considerations to questions of right and wrong, such as “whether or not a person suffered emotionally” (Care), or “whether or not someone did something to betray their group” (Loyalty). The judgment section consists of 15 agree/disagree items, such as “justice is the most important requirement for a society” (Fairness) and “chastity is an important and valuable virtue” (Sanctity).

While the MFQ has been extensively validated (Graham et al., 2011), its design limits the types of questions that can be addressed with it. Most crucially, the MFQ largely relies on respondents’ rating of abstract principles, rather than judgment of concrete scenarios. As Graham et al. argue (2009, p.1031), moral relevance “does not necessarily measure how people actually make moral judgments,” but these ratings are “best understood as self-theories about moral judgment.” Yet, individuals’ theories of morality (i.e., endorsement of moral principles) might diverge from their specific moral judgments (Haidt, 2001). For example, one might view harm or loyalty as highly relevant to morality, yet refrain from making harsh judgments about others’ harmful or disloyal behavior. Moreover, many of these items include an “unstated, and ambiguous referent,” such as an authority figure, yet people may “judge MFT issues differently depending on the referents” (Frimer, Biesanz, Walker, & MacKinlay, 2013, p. 1053). Furthermore, some have argued that the MFQ may be overstating ideological divides in morality by focusing on “points of disagreement between partisans—controversial issues (e.g., chastity)—issues unrepresentative of the full spectrum of moral judgments that people make” (Frimer et al., 2013, p. 1053). These authors call for a broader set of cases to explore judgments of right and wrong.

Some researchers have used the MFQ as a dependent variable (Lee, Sohn, & Fowler, 2013; Napier & Luguri, 2013; Wright & Baril, 2011), but it’s unclear how these relationships would translate to moral judgment. Notably, some of these authors even refer to the MFQ as a measure of “moral judgment,” highlighting the need for such a measure (Lee, Sohn, & Fowler, 2013). Moreover, neither the MFQ nor MFSS is ideally suited for techniques measuring neural activity. The brevity of the scales would lead to insufficient statistical power and additionally, the lack of control for stimulus length and complexity may introduce potential confounds. Indeed, some prior evidence shows that simple variations to syntactic structure, including length, can lead to differences in neural activity (Baciu, Ans, & Carbonnel, 2002; Church, Balota, Petersen, & Schlaggar, 2011; Hauk & Pulvermüller, 2004).

Alternatively, some research has employed the Moral Foundations Sacredness Scale (MFSS), which was designed to test respondents’ willingness to engage in taboo tradeoffs (Tetlock, Kristel, Elson, Green, & Lerner, 2000), such as kicking a dog in the head (Care) or renouncing one’s citizenship (Loyalty) for money (Graham et al., 2009). However, the MFSS is designed to measure an individual’s willingness to violate moral norms in exchange for money, as opposed to judgments of others’ behaviors.

Finally, numerous papers have used variations of vignettes on a more ad hoc basis. For example, two scenarios involving incest and sex with a dead chicken have been used frequently in research on moral judgment (Feinberg, Willer, Antonenko, & John, 2012; Pennycook, Cheyne, Barr, Koehler, & Fugelsang, 2013). Other researchers have used vignettes including incest and eating a pet dog (Eskine, Kacinik, & Prinz, 2011; Schnall, Haidt, Clore, & Jordan, 2008; Wheatley & Haidt, 2005). Within the neuroimaging literature, researchers have typically constructed their own moral vignettes on an ad hoc basis with some devising scenarios corresponding to the harm and purity moral foundations (Heekeren et al., 2005; Parkinson et al., 2011; Schaich Borg et al., 2008; Schaich Borg et al., 2011). Other neuroimaging studies have used pictorial stimuli to depict certain moral violations but collapse across all forms of violations in their analyses, making it difficult to examine potential differences between specific moral foundations (Harenski, Antonenko, Shane, & Kiehl, 2008; Harenski & Hamann, 2006; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002). Overall, researchers have relied on a variety of different moral vignettes, many of which have not been normed and none of which cover the full breadth of the moral domain. Though we believe the MFV will be useful for a wide variety of research, below we discuss two areas of research in which we believe the MFV will be particularly useful.

Emotion and moral judgment

A growing literature examines the effects of emotion on moral judgment. Much research has focused specifically on the role of disgust, with some arguing that disgust causes harsher moral judgments (Eskine et al., 2011; Pizarro, Inbar, & Helion, 2011; Schnall et al., 2008; Wheatley & Haidt, 2005) and others arguing that disgust uniquely affects judgments in the Sanctity domain (Horberg, Oveis, Keltner, & Cohen, 2009; Horberg, Oveis, & Keltner, 2011). More recently, some have argued that arousal, rather than specific emotions, are the driving force behind moral judgments (Cheng, Ottati, & Price, 2013). Yet, as noted by Horberg et al. (2009), the absence of a standardized set of scenarios that violate particular moral foundations makes it difficult to ascertain the specific effects of emotions across moral domains.

The neurological bases of moral judgment

MFT holds that morality follows a five (or six) factor structure with each moral foundation corresponding to separate modules (Haidt, 2013). Whether morality is unified or can be deconstructed into five or fewer factors has been a question of debate (Sinnott-Armstrong, 2007) that could benefit from neuroimaging studies of moral judgment. Initial fMRI evidence points to morality as a non-unified construct, with distinct brain areas for judgments of disgust, honesty, and harm-based violations (Parkinson et al., 2011), though this study was not explicitly framed in terms of the moral foundations.1 Furthermore, another study found different brain regions corresponding to the binding and individualizing superordinate moral foundations (Lewis et al., 2012). Neuroimaging techniques such as fMRI could also prove useful in testing cross-cultural differences found for judgments of moral violations (Graham et al., 2011), given evidence that cultural differences may influence both the location and levels of observed neural activity (for a review see Han & Northoff, 2008). While fMRI studies of morality are potentially useful for testing MFT, due to an absence of a standardized stimulus set, most have focused only on a subset of moral domains, such as purity (Moll et al., 2005; Schaich Borg et al., 2008), harm (Heekeren et al., 2005), fairness (Robertson et al., 2007), or a subset of the moral foundations (Parkinson et al., 2011), and consequently are unable to compare and contrast all of the moral domains.

Development of a standardized stimulus set of moral vignettes

In order to aid researchers in addressing some of the theoretical questions discussed above, we sought to design a new stimulus set that would satisfy the following criteria: a) measure judgment of concrete behaviors, b) contain subsets mapping onto the moral foundations, c) contain a subset of social norm (i.e., non-moral) violations, and d) be suitable for use in behavioral and neuroimaging paradigms. Notably, we do not view these vignettes as measuring every aspect of morality. Our vignettes focuses specifically on judgment of third-party moral violations, as opposed to separable dimensions such as moral praise (Wiltermuth, Monin, & Chow, 2010) or moral character (Chadwick, Bromgard, Bromgard, & Trafimow, 2006).

We began by writing a large number of scenarios representing face valid violations of particular moral foundations, adapting previous stimuli whenever possible. Because our moral intuitions are argued to have evolved in response to social interactions in small group settings, we focus the content of our scenarios on events that could plausibly occur in everyday life. We made an effort to vary the content of scenarios within any given foundation in order to reduce redundancy, avoid interactions with memory, and ensure full conceptual coverage of the foundation. It was also important to avoid overtly political content and reference to particular social groups in order to avoid tautological claims in political research. Furthermore, we tried to avoid scenarios that might require temporally or culturally bounded knowledge. Finally, we made an effort to eliminate any reference to other foundations to increase the likelihood of isolating the influence of a particular moral foundation.

We also took several steps to ensure that our vignettes are suitable for use in neuroimaging studies of moral judgment. First, we constrained the length of the scenarios (14–17 words, 60–70 characters) and maximized readability and comprehensibility by limiting the reading level to above 30 (ranging from 35.5 – 95.7 with an average of 70.8) and reading ease to below 12 (ranging from 3.6–11.7 with an average of 7.08) as measured by the Flesch-Kincaid reading level and reading ease indices.

Second, to encourage respondents to visualize themselves as third-party witnesses, all of our scenarios begin with a “You see…” formulation. For example, a Care violation reads: “You see a girl telling a boy that his older brother is much more attractive than him.” This structure ensures that respondents imagine a third party committing the violation and that any emotions evoked are the result of imagining witnessing the transgression (for a related approach, see Cannon, Schnall, & White, 2010).

Finally, we created a set of social norms violations that were intended to be unusual but not considered morally wrong (for example, drinking coffee with a spoon). The social norms will play an important role in serving as a control stimulus set in neuroimaging studies of moral judgment by allowing for a comparison between appraisals of scenarios that depict a moral violation and scenarios that depict a social, but not moral, violation. Additionally, the social norms violations prevent respondents from expecting a morally loaded transgression in every scenario. Non-moral control conditions have been used in several fMRI studies to identify the neural circuitry involved when making moral judgments (Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Bramati, et al., 2002; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002; Parkinson et al., 2011). Below we detail the specific guidelines used to construct scenarios for each moral foundation.

For the Care foundation, we focused on three forms of harm that reflect the diversity of the original conception of Care: emotional harm to a human, physical harm to a human, and physical harm to a non-human animal. This division of Care also reflects evidence from an fMRI study showing that the introduction of bodily harm into either a moral or non-moral scenario can influence the levels of observed neural activity in certain brain regions (Heekeren et al., 2005). To avoid confounds with the Authority and Liberty moral foundations, we avoided any scenarios that invoked a social hierarchy (pretesting suggested that downward harm in a social hierarchy invoked Liberty, while upward harm invoked Authority). Additionally, we focused on scenarios involving strangers to avoid Loyalty considerations.

Fairness vignettes focused on instances of cheating or free riding (e.g., cheating on a test, lying about work hours). Again, we avoided scenarios involving close-knit groups that might invoke Loyalty. Additionally, we attempted to avoid scenarios involving disobedience towards a superior, which might invoke Authority. We avoided instances of unfairness involving race, gender, or structural inequality due to concerns that they would measure political and social attitudes more than moral concerns.

Loyalty violations consisted of individuals putting their own interests ahead of their group, with group defined as family, country, sports team, school, or company. Throughout our testing, we developed three guidelines for an effective Loyalty violation: the behavior occurs publicly to threaten the reputation of the group, there is a clear out-group in competition with the actor’s group, and the actor is perceived as a spokesperson or identifiable member of the group. This characterization of Loyalty is somewhat narrower than usual in the moral foundations literature, but we wanted to avoid scenarios with overt harm that might create a confound with the Care foundation.

Authority violations primarily consisted of disobedience or disrespect towards traditional authority figures (e.g., a boss, judge, teacher, or parent) or towards an institution or symbol of authority (e.g., courthouse, police department).

Sanctity violations include sexually deviant acts (promiscuity, incest), as well as behaviors that would be considered degrading (drunkenly making out with strangers on a bus) or raise contamination concerns (urinating in a public pool, using a stranger’s toothbrush). Additionally, we included vignettes inspired by previous research, such as eating a dead pet dog (Haidt, Koller, & Dias, 1993). Notably, all of our scenarios include elements of physical disgust. We focused on physical disgust in order to avoid disputes about whether moral disgust (which might be directed towards political corruption or sick motives) really is the same emotion as physical disgust. Some have suggested that certain symbols, such as a church, cross, or flag, can become sacralized (Haidt, 2013). However, we chose not to include any violations of sacred objects due to concerns that a symbol may become sacralized for reasons related to other moral foundations, creating a confound in the scenario.

Liberty vignettes consisted of behaviors that are coercive or reduce freedom of choice, particularly actions by those in a position of power over another person (e.g., a man forcing his wife to change her religion). Agents in these scenarios include parents, husbands, bosses, and social leaders.

Finally, we created a set of scenarios that represented a violation of social norms, in that they would be seen as unusual, but not morally wrong. We also sought to avoid any content related to a particular moral foundation. Examples include lifting weights in business clothes and wearing a large sun hat indoors.

Study 1

We first sought to validate our scenarios by asking respondents to rate the moral wrongness of each behavior, as well as why they believe each behavior is morally wrong. This first step ensured that people understood the scenarios as intended and further reduced the inter-subject variability that may arise due to differences in how respondents classified the particular moral violation. A similar procedure has been employed in a previous fMRI investigation of a subset of the moral foundations (Parkinson et al., 2011) as well as research on the impact of disgust on moral judgment (Horberg et al., 2009). Additionally, we asked respondents to rate the scenarios on imageability, vividness, arousal, frequency, and comprehension.

Method

Respondents were recruited in three waves (n = 330, 192, 94) from a national online panel by Qualtrics. After each wave, we discarded or modified scenarios that did not meet our requirements (described below), then fielded a new wave of the study to test new and modified scenarios. Respondents were limited to the age range of 18–40 (M = 35, 32, 33), similar to the age range of respondents used in several previous fMRI investigations of moral judgments (Greene, Nystrom, Engell, Darley, & Cohen, 2004; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Bramati, et al., 2002; Moll, de Oliveira-Souza, Eslinger, et al., 2002; Schaich Borg, Sinnott-Armstrong, Calhoun, & Kiehl, 2011) and balanced on ideology (to maintain an equal number of liberals, moderates, and conservatives). We also screened out respondents who failed an instructional manipulation check at the beginning of the survey (Berinsky, Margolis, & Sances, 2013; Oppenheimer, Meyvis, & Davidenko, 2009). The first sentence of the question asked respondents which sections of the newspaper they like to read, while the remaining three sentences instructed respondents to select “classifieds” and “none of the above.” Respondents who did not follow the instructions were considered inattentive and not allowed to complete the survey.

Measures

Respondents were given a random subset (14–16) of the vignettes such that each vignette was rated by approximately 30 individuals. Respondents were first asked to rate how morally wrong the behavior is on a 5-point scale labeled not at all wrong, not too wrong, somewhat wrong, very wrong, extremely wrong. Next respondents were asked “Why is the action morally wrong? (Select the main reason.)” Response options corresponded with each of the moral foundations:

It violates norms of harm or care (e.g., unkindness, causing pain to another)

It violates norms of fairness or justice (e.g., cheating or reducing equality)

It violates norms of loyalty (e.g., betrayal of a group)

It violates norms of respecting authority (e.g., subversion, lack of respect for tradition)

It violates norms of purity (e.g., degrading or disgusting acts)

It violates norms of freedom (e.g., bullying, dominating)

It is not morally wrong and does not apply to any of the provided choices

Crucially, we did not use any of the words from the descriptions of the foundations (e.g., betrayal, degrading) in the actual vignettes, minimizing concerns that classification is driven by shared language.2 Next respondents were asked to rate the comprehensibility (“How easy is it for you to understand what is described in the scenario?”), imageability (“How easy is it for you to clearly imagine what is happening in the scenario?”), frequency (“How often do you see or hear about actions like the one described in this scenario in the media or your daily life?”), and the strength of their emotional response (“How strong was your emotional response to the behavior depicted in this scenario?”) all on 5-point fully-labeled scales.

Results and discussion

Table 1 displays the results of Study 1, retaining only scenarios that met two criteria. First, at least 60 % of respondents must have classified the scenario as violating the intended moral foundation. Second, we excluded scenarios for which 20 % or more of respondents classified the scenario as violating a particular unintended foundation (e.g., 20 % selected Liberty as the reason why a Care violation is wrong).

Table 1.

Respondent ratings of moral scenarios

| Scenario | Respondent Classifications of Scenarios

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Care | Fairness | Loyalty | Authority | Sanctity | Liberty | Not Wrong | Wrong | |

| You see a teenage boy chuckling at an amputee he passes by while on the subway. | Care (e) | 83 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 10 % | 3 % | 0 % | 3.4 |

| You see a girl laughing at another student forgetting her lines at a school play. | Care (e) | 73 % | 3 % | 7 % | 0 % | 0 % | 13 % | 3 % | 2.4 |

| You see a woman commenting out loud about how fat another woman looks in her jeans. | Care (e) | 73 % | 7 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 13 % | 0 % | 3.0 |

| You see a man quickly canceling a blind date as soon as he sees the woman. | Care (e) | 72 % | 16 % | 0 % | 0 % | 6 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3.0 |

| You see a boy telling a woman that she looks just like her overweight bulldog. | Care (e) | 72 % | 0 % | 0 % | 13 % | 0 % | 16 % | 0 % | 3.3 |

| You see a girl laughing when she realizes her friend’s dad is the janitor. | Care (e) | 70 % | 7 % | 0 % | 3 % | 7 % | 10 % | 3 % | 2.9 |

| You see a man snickering as he passes by a cancer patient with a bald head. | Care (e) | 69 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 17 % | 10 % | 0 % | 3.4 |

| You see a girl saying that another girl is too ugly to be a varsity cheerleader. | Care (e) | 69 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 7 % | 14 % | 7 % | 2.8 |

| You see a teenage girl openly staring at a disfigured woman as she walks past. | Care (e) | 68 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 23 % | 2.0 |

| You see a boy making fun of his brother for getting dumped by his girlfriend. | Care (e) | 68 % | 0 % | 13 % | 0 % | 0 % | 10 % | 10 % | 2.2 |

| You see a man laughing at a disabled co-worker while at an office softball game. | Care (e) | 68 % | 6 % | 0 % | 0 % | 6 % | 19 % | 0 % | 3.5 |

| You see a man loudly telling his wife that the dinner she cooked tastes awful. | Care (e) | 66 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 13 % | 6 % | 9 % | 2.4 |

| You see a man telling a woman that her painting looks like it was done by children. | Care (e) | 66 % | 0 % | 0 % | 6 % | 0 % | 16 % | 13 % | 1.9 |

| You see a woman clearly avoiding sitting next to an obese woman on the bus. | Care (e) | 64 % | 7 % | 0 % | 4 % | 4 % | 4 % | 18 % | 2.0 |

| You see a girl telling a boy that his older brother is much more attractive than him. | Care (e) | 63 % | 3 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 25 % | 1.4 |

| You see a girl telling her classmate that she looks like she has gained weight. | Care (e) | 60 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 13 % | 10 % | 10 % | 2.2 |

| You see a woman swerving her car in order to intentionally run over a squirrel. | Care (p, a) | 87 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 5 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3.2 |

| You see a woman throwing her cat across the room for scratching the furniture. | Care (p, a) | 85 % | 2 % | 0 % | 2 % | 5 % | 5 % | 0 % | 3.2 |

| You see a boy throwing rocks at cows that are grazing in the local pasture. | Care (p, a) | 85 % | 0 % | 2 % | 5 % | 5 % | 2 % | 0 % | 3.3 |

| You see a man lashing his pony with a whip for breaking loose from its pen. | Care (p, a) | 83 % | 0 % | 0 % | 2 % | 7 % | 5 % | 2 % | 2.9 |

| You see a boy setting a series of traps to kill stray cats in his neighborhood. | Care (p, a) | 81 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 14 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3.6 |

| You see a zoo trainer jabbing a dolphin to get it to entertain his customers. | Care (p, a) | 76 % | 2 % | 5 % | 5 % | 2 % | 7 % | 2 % | 3.2 |

| You see someone leaving his dog outside in the rain after it dug in the trash. | Care (p, a) | 75 % | 0 % | 8 % | 3 % | 5 % | 3 % | 8 % | 2.7 |

| You see a girl shooting geese repeatedly with a pellet gun out in the woods. | Care (p, a) | 69 % | 0 % | 0 % | 5 % | 13 % | 5 % | 8 % | 3.0 |

| You see a woman snatching away her dog’s food for making a mess in the living room. | Care (p, a) | 63 % | 6 % | 3 % | 0 % | 3 % | 9 % | 17 % | 2.2 |

| You see a woman throwing a stapler at her colleague who is snoring during her talk. | Care (p, h) | 78 % | 3 % | 3 % | 8 % | 0 % | 5 % | 3 % | 3.0 |

| You see a teacher hitting a student’s hand with a ruler for falling asleep in class. | Care (p, h) | 78 % | 0 % | 3 % | 5 % | 3 % | 8 % | 3 % | 2.7 |

| You see a woman slapping another woman who she is arguing with in the parking lot. | Care (p, h) | 78 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 5 % | 13 % | 3 % | 2.8 |

| You see a girl throwing her hot coffee on a woman who is dating her ex-boyfriend | Care (p, h) | 73 % | 0 % | 8 % | 5 % | 5 % | 8 % | 3 % | 3.3 |

| You see a wife hitting her husband on the side of his head for coming home late. | Care (p, h) | 69 % | 8 % | 5 % | 0 % | 3 % | 15 % | 0 % | 2.9 |

| You see a boy placing a thumbtack sticking up on the chair of another student. | Care (p, h) | 65 % | 0 % | 10 % | 8 % | 3 % | 13 % | 3 % | 2.8 |

| You see a woman spanking her child with a spatula for getting bad grades in school. | Care (p, h) | 62 % | 3 % | 5 % | 0 % | 5 % | 10 % | 15 % | 2.6 |

| You see a student copying a classmate’s answer sheet on a makeup final exam. | Fairness | 0 % | 100 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3.4 |

| You see a runner taking a shortcut on the course during the marathon in order to win. | Fairness | 0 % | 97 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3.4 |

| You see a tenant bribing a landlord to be the first to get their apartment repainted. | Fairness | 0 % | 97 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 2.2 |

| You see a soccer player pretending to be seriously fouled by an opposing player. | Fairness | 0 % | 94 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 2.5 |

| You see someone cheating in a card game while playing with a group of strangers. | Fairness | 3 % | 93 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 2.6 |

| You see a professor giving a bad grade to a student just because he dislikes him. | Fairness | 3 % | 93 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3.7 |

| You see a referee intentionally making bad calls that help his favored team win. | Fairness | 0 % | 90 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3.0 |

| You see a manager taking half the doughnuts from a box, leaving little for others. | Fairness | 3 % | 90 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 7 % | 2.0 |

| You see a judge taking on a criminal case although he is friends with the defendant. | Fairness | 0 % | 89 % | 4 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 7 % | 3.1 |

| You see a student getting an A on a group project when he didn’t do his part. | Fairness | 0 % | 88 % | 9 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 2.8 |

| You see an employee lying about how many hours she worked during the week. | Fairness | 0 % | 87 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 3 % | 2.9 |

| You see a woman getting hired only because her father is close friends with the boss. | Fairness | 0 % | 84 % | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 3 % | 6 % | 2.4 |

| You see a girl asking for allowance even though her brother did her chores for her. | Fairness | 3 % | 82 % | 3 % | 6 % | 6 % | 0 % | 0 % | 2.7 |

| You see a girl taking all the Halloween candy from a bowl, leaving none for others. | Fairness | 6 % | 74 % | 10 % | 6 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 2.5 |

| You see a politician using federal tax dollars to build an extension on his home. | Fairness | 3 % | 71 % | 19 % | 3 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 3.8 |

| You see a boy skipping to the front of the line because his friend is an employee. | Fairness | 3 % | 70 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 13 % | 2.4 |

| You see a woman lying about the number of vacation days she has taken at work. | Fairness | 0 % | 60 % | 10 % | 7 % | 0 % | 0 % | 23 % | 2.2 |

| You see an employee joking with competitors about how bad his company did last year. | Loyalty | 0 % | 3 % | 84 % | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 6 % | 2.0 |

| You see a coach celebrating with the opposing team’s players who just won the game. | Loyalty | 0 % | 3 % | 76 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 17 % | 1.8 |

| You see a former US General saying publicly he would never buy any American product. | Loyalty | 0 % | 0 % | 75 % | 6 % | 3 % | 0 % | 16 % | 2.5 |

| You see a mayor saying that the neighboring town is a much better town. | Loyalty | 0 % | 3 % | 74 % | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 16 % | 1.6 |

| You see the US Ambassador joking in Great Britain about the stupidity of Americans. | Loyalty | 3 % | 0 % | 74 % | 16 % | 0 % | 0 % | 6 % | 2.8 |

| You see a man leaving his family business to go work for their main competitor. | Loyalty | 0 % | 3 % | 73 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 20 % | 1.7 |

| You see a teacher publicly saying she hopes another school wins the math contest. | Loyalty | 12 % | 0 % | 69 % | 0 % | 4 % | 0 % | 15 % | 1.9 |

| You see a head cheerleader booing her high school’s team during a homecoming game. | Loyalty | 7 % | 0 % | 69 % | 7 % | 0 % | 7 % | 10 % | 2.3 |

| You see the class president saying on TV that her rival college is a better school. | Loyalty | 0 % | 0 % | 68 % | 6 % | 0 % | 0 % | 26 % | 1.4 |

| You see a Hollywood star agreeing with a foreign dictator’s denunciation of the US. | Loyalty | 0 % | 3 % | 67 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 27 % | 2.2 |

| You see a college president singing a rival school’s fight song during a pep rally. | Loyalty | 0 % | 0 % | 66 % | 7 % | 3 % | 0 % | 24 % | 1.7 |

| You see a man secretly voting against his wife in a local beauty pageant. | Loyalty | 10 % | 7 % | 66 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 17 % | 1.9 |

| You see an American telling foreigners that the US is an evil force in the world. | Loyalty | 10 % | 0 % | 66 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 14 % | 2.7 |

| You see the coach’s wife sponsoring a bake sale for her husband’s rival team. | Loyalty | 0 % | 6 % | 65 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 29 % | 1.5 |

| You see a former Secretary of State publicly giving up his citizenship to the US. | Loyalty | 0 % | 3 % | 62 % | 10 % | 0 % | 7 % | 17 % | 2.1 |

| You see a US swimmer cheering as a Chinese foe beats his teammate to win the gold. | Loyalty | 2 % | 2 % | 61 % | 7 % | 0 % | 0 % | 27 % | 1.8 |

| You see a girl ignoring her father’s orders by taking the car after her curfew. | Authority | 3 % | 0 % | 6 % | 81 % | 3 % | 0 % | 6 % | 2.5 |

| You see a woman refusing to stand when the judge walks into the courtroom. | Authority | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 80 % | 3 % | 0 % | 13 % | 2.0 |

| You see a girl repeatedly interrupting her teacher as he explains a new concept. | Authority | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 80 % | 0 % | 0 % | 17 % | 2.0 |

| You see a woman spray painting graffiti across the steps of the local courthouse. | Authority | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 78 % | 16 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3.3 |

| You see an intern disobeying an order to dress professionally and comb his hair. | Authority | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 78 % | 0 % | 0 % | 19 % | 1.9 |

| You see a man turn his back and walk away while his boss questions his work. | Authority | 2 % | 0 % | 2 % | 78 % | 0 % | 0 % | 17 % | 2.1 |

| You see a staff member talking loudly and interrupting the mayor’s speech to the public. | Authority | 0 % | 8 % | 8 % | 76 % | 5 % | 3 % | 0 % | 2.8 |

| You see a teenage girl coming home late and ignoring her parents’ strict curfew. | Authority | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 75 % | 3 % | 0 % | 13 % | 2.3 |

| You see a boy spray-painting anarchy symbols on the side of the police station. | Authority | 6 % | 0 % | 0 % | 75 % | 9 % | 3 % | 6 % | 2.9 |

| You see an employee trying to undermine all of her boss’ ideas in front of others. | Authority | 7 % | 0 % | 13 % | 73 % | 0 % | 0 % | 7 % | 2.6 |

| You see a teaching assistant talking back to the teacher in front of the classrom. | Authority | 3 % | 0 % | 13 % | 72 % | 3 % | 3 % | 8 % | 2.5 |

| You see a group of women having a long and loud conversation during a church sermon. | Authority | 3 % | 0 % | 15 % | 72 % | 10 % | 0 % | 0 % | 2.8 |

| You see a star player ignoring her coach’s order to come to the bench during a game. | Authority | 0 % | 10 % | 13 % | 71 % | 0 % | 0 % | 6 % | 2.1 |

| You see a player publicly yelling at his soccer coach during a playoff game. | Authority | 7 % | 3 % | 3 % | 69 % | 3 % | 10 % | 3 % | 2.1 |

| You see a man secretly watching sports on his cell phone during a pastor’s sermon. | Authority | 7 % | 3 % | 3 % | 69 % | 0 % | 0 % | 17 % | 1.8 |

| You see a boy turning up the TV as his father talks about his military service. | Authority | 13 % | 0 % | 0 % | 65 % | 0 % | 0 % | 23 % | 2.1 |

| You see a student stating that her professor is a fool during an afternoon class. | Authority | 13 % | 3 % | 6 % | 65 % | 0 % | 0 % | 13 % | 2.0 |

| You see a man having sex with a frozen chicken before cooking it for dinner. | Sanctity | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 88 % | 3 % | 6 % | 3.0 |

| You see a very drunk woman making out with multiple strangers on the city bus. | Sanctity | 3 % | 8 % | 3 % | 0 % | 85 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3.0 |

| You see a family eating the carcass of their pet dog that had been run over. | Sanctity | 3 % | 3 % | 6 % | 3 % | 84 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3.2 |

| You see a drunk elderly man offering to have oral sex with anyone in the bar. | Sanctity | 6 % | 0 % | 0 % | 6 % | 84 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3.4 |

| You see a teenager urinating in the wave pool at a crowded amusement park. | Sanctity | 13 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 84 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3.4 |

| You see a man in a bar using his phone to watch people having sex with animals. | Sanctity | 10 % | 6 % | 3 % | 3 % | 77 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3.3 |

| You see a teenage male in a dorm bathroom secretly using a stranger’s toothbrush. | Sanctity | 13 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 77 % | 3 % | 6 % | 2.6 |

| You see a woman having intimate relations with a recently deceased loved one. | Sanctity | 6 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 74 % | 3 % | 10 % | 3.3 |

| You see a homosexual in a gay bar offering sex to anyone who buys him a drink. | Sanctity | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 7 % | 73 % | 3 % | 13 % | 2.6 |

| You see an employee at a morgue eating his pepperoni pizza off of a dead body. | Sanctity | 7 % | 0 % | 0 % | 10 % | 73 % | 0 % | 10 % | 3.2 |

| You see a girl and her sister making out with each other just for practice. | Sanctity | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 71 % | 0 % | 23 % | 2.8 |

| You see a story about a remote tribe eating the flesh of their deceased members. | Sanctity | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 69 % | 0 % | 24 % | 2.3 |

| You see a woman burping and farting loudly while eating at a fast food truck. | Sanctity | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 6 % | 68 % | 3 % | 19 % | 2.1 |

| You see a man searching through the trash to find women’s discarded underwear. | Sanctity | 9 % | 0 % | 3 % | 12 % | 67 % | 3 % | 6 % | 3.0 |

| You see two first cousins getting married to each other in an elaborate wedding. | Sanctity | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 13 % | 66 % | 3 % | 16 % | 2.7 |

| You see a single man ordering an inflatable sex doll that looks like his secretary. | Sanctity | 0 % | 6 % | 0 % | 3 % | 65 % | 0 % | 26 % | 1.5 |

| You see a college student drinking until she vomits on herself and falls asleep. | Sanctity | 5 % | 0 % | 0 % | 5 % | 64 % | 0 % | 26 % | 2.3 |

| You see a man telling his fiance that she has to switch to his political party. | Liberty | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 90 % | 3 % | 2.9 |

| You see a father requiring his son to become a commercial airline pilot like him. | Liberty | 0 % | 4 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 85 % | 12 % | 1.9 |

| You see a man blocking his wife from leaving home or interacting with others. | Liberty | 6 % | 6 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 84 % | 0 % | 3.3 |

| You see a manager coercing her employees into eating at her brother’s diner. | Liberty | 0 % | 10 % | 3 % | 3 % | 3 % | 77 % | 3 % | 2.2 |

| You see a man telling his girlfriend that she must convert to his religion. | Liberty | 0 % | 13 % | 3 % | 6 % | 0 % | 77 % | 0 % | 2.5 |

| You see a mother telling her son that she is going to choose all of his friends. | Liberty | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 75 % | 19 % | 2.2 |

| You see a man forbidding his wife to wear clothing that he has not first approved. | Liberty | 6 % | 10 % | 3 % | 0 % | 3 % | 74 % | 3 % | 3.1 |

| You see a boss ordering an employee to revoke his citizenship in his home country. | Liberty | 3 % | 7 % | 17 % | 3 % | 0 % | 70 % | 0 % | 3.3 |

| You see a boss pressuring employees to buy goods from her family’s general store. | Liberty | 3 % | 10 % | 3 % | 0 % | 10 % | 69 % | 3 % | 2.7 |

| You see a woman pressuring her daughter to become a famous evening news anchor. | Liberty | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 68 % | 26 % | 1.5 |

| You see a public leader on TV trying to ban the wearing of hooded sweatshirts. | Liberty | 3 % | 19 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 65 % | 10 % | 2.7 |

| You see a mother forcing her daughter to enroll as a pre-med student in college. | Liberty | 10 % | 6 % | 0 % | 6 % | 3 % | 65 % | 10 % | 2.3 |

| You see a father requiring his son to take up the family restaurant business. | Liberty | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 7 % | 3 % | 62 % | 21 % | 1.5 |

| You see a teacher ordering a student to get a normal haircut before coming to class. | Liberty | 0 % | 19 % | 0 % | 0 % | 8 % | 62 % | 12 % | 2.8 |

| You see a teenager at a cafeteria forcing a younger student to pay for her lunch. | Liberty | 13 % | 10 % | 3 % | 6 % | 3 % | 61 % | 3 % | 3.0 |

| You see a mayor trying to ban people from hugging and kissing in public in his city. | Liberty | 5 % | 8 % | 3 % | 10 % | 0 % | 69 % | 5 % | 3.2 |

| You see a pastor banning his congregants from wearing bright colors in the church. | Liberty | 3 % | 3 % | 8 % | 10 % | 3 % | 62 % | 13 % | 2.6 |

| You see someone using an old rotary phone and refusing to go buy a new one. | Social Norms | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 100 % | 0.0 |

| You see a man staying inside his home with the shades drawn on a rare sunny day. | Social Norms | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 100 % | 0.1 |

| You see a woman drinking her entire cup of coffee using a stirring spoon. | Social Norms | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 97 % | 0.2 |

| You see a woman eating dessert before her main entree arrives on the table. | Social Norms | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 97 % | 0.2 |

| You see a woman continuing to wear a large sun hat inside her apartment complex. | Social Norms | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 97 % | 0.2 |

| You see someone at the school gym lifting free weights in nice business clothes. | Social Norms | 0 % | 4 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 96 % | 0.2 |

| You see a man eating a bowl of cereal in the morning with water instead of milk. | Social Norms | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 94 % | 0.1 |

| You see a woman using a fork to eat a bowl of vanilla ice cream and marshmallows. | Social Norms | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 94 % | 0.1 |

| You see a man putting ketchup all over his chicken Caesar salad while at lunch. | Social Norms | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 94 % | 0.2 |

| You see a man wearing clothes that are clearly several sizes too big for his body. | Social Norms | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 93 % | 0.3 |

| You see a man walking down a dark hallway while still wearing his sunglasses. | Social Norms | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 93 % | 0.2 |

| You see someone driving around in a dirty car that has not been washed recently. | Social Norms | 0 % | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 6 % | 0 % | 91 % | 0.2 |

| You see a woman watching a game on television in black-and-white instead of color. | Social Norms | 0 % | 0 % | 3 % | 0 % | 7 % | 0 % | 90 % | 0.1 |

| You see someone reading the ending of a spy novel before reading the beginning. | Social Norms | 4 % | 0 % | 4 % | 0 % | 0 % | 4 % | 89 % | 0.2 |

| You see a teenage girl wearing a long trench coat on a hot summer afternoon. | Social Norms | 3 % | 3 % | 0 % | 6 % | 0 % | 0 % | 88 % | 0.2 |

| You see a woman answering a phone call with the word “goodbye” instead of “hello. | Social Norms | 3 % | 0 % | 0 % | 10 % | 0 % | 0 % | 87 % | 0.5 |

“Care (e)” refers to emotional harm scenarios, “Care (p, h)” to physical harm to a human, and “Care (p, a)” to physical harm to a nonhuman animal. “Wrong” represents average ratings of moral wrongness on a 5-point scale, where 0 = not at all wrong and 4 = extremely wrong.

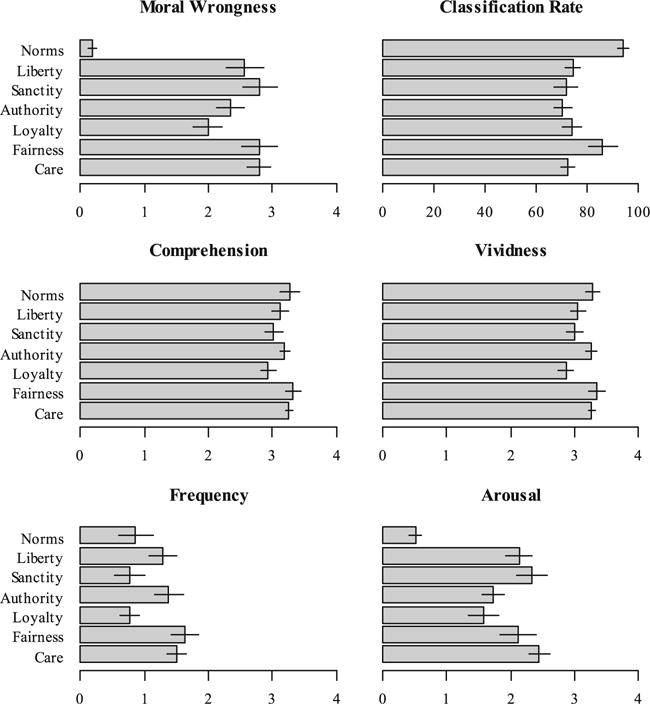

The average ratings within each foundation are shown in Fig. 1. The top left panel shows the average wrongness ratings for each foundation, which range from 2.0 (Loyalty) to 2.8 (Sanctity), with social norms averaging 0.2 (scales range from 0 to 4). Notably, the Loyalty violations were rated the least wrong among the foundations, with respondents rating them as “somewhat wrong” on average. The top right panel shows the average percentage of respondents correctly classifying why a behavior is wrong. Average within-foundation classification rates range from 69 % (Care) to 94 % (social norms). The middle row of the figure shows the average comprehension (left) and vividness ratings (right). As shown in the middle row of the figure, all foundations received high comprehension ratings (2.9–3.3) and high vividness ratings (2.8–3.3). Additionally, we collected ratings of stimulus frequency, as some have suggested that stimulus familiarity is a factor potentially driving the differences in evaluations of stimuli belonging to different categories (Somerville & Whalen, 2006). Across the foundations, the vignettes were rated as fairly uncommon (bottom left panel), ranging from 0.7 to 1.7.

Fig. 1.

Foundation-level ratings of moral vignettes

Finally, the foundations all induced moderately strong emotional responses (1.6–2.3), with the exception of social norms (0.5). This is unsurprising, as emotional arousal is highly correlated with moral wrongness ratings in our data. Overall, the results suggest that respondents shared a clear and common understanding of the scenarios, and that there are few differences between the foundations in terms of the frequency of the depicted behaviors. Our findings also support the validity of our social norms scenarios, as they were rated low on wrongness and arousal, yet also low on frequency.

Study 2

As our next step we sought to validate the scenarios by establishing internal validity through factor analysis and criterion validity with existing measures of the moral foundations (MFQ and MFSS).

Method

We recruited 510 respondents from a national online panel through Qualtrics. Respondents were limited to the age range of 18–40 and balanced on ideology (to maintain an equal number of liberals, moderates, and conservatives). We also screened out respondents who failed an instructional manipulation check at the beginning of the survey (Berinsky, Margolis, & Sances, 2013; Oppenheimer, Meyvis, & Davidenko, 2009). Respondents were asked what they were doing at that moment. Respondents who selected swimming or riding a bike were excluded, as were respondents who did not report using a computer or electronic device.

Measures

Respondents were asked to rate the moral wrongness of all 132 scenarios that met the criteria established in Study 1, fill out the Moral Foundations Questionnaire and Sacredness Scale (Graham et al., 2009), and answer basic political and demographic questions. Respondents were randomly assigned to fill out the MFQ either before or after making the moral judgments. Respondents who failed either of two attention checks embedded in the MFQ were removed from analysis (n = 94).3 For respondents passing both checks, the correlation between ideology and partisan identification was r(416) = .62, p < .001, for respondents failing at least one check, the correlation was r(96) = .21, p = .04. This suggests that the attention checks were effectively picking out inattentive respondents.

Results and discussion

Although we have a predicted factor structure, we begin with an exploratory factor analysis to examine the extent to which individual scenarios load cleanly onto the expected factors, and not others. Respondents’ wrongness ratings for all moral scenarios, with the exception of social norms violations, were entered as manifest variables in a maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis.4 A parallel analysis was then conducted, which indicated that nine factors should be retained. The nine factors were then submitted to promax rotation. Results are shown in Table 2 with factor loadings greater than or equal to .4 in bold and factor loadings less than .3 in gray.

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis of moral judgments

| Foundation | Scenario | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care (e) | You see a teenage boy chuckling at an amputee he passes by while on the subway. | 0.46 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.22 | −0.20 | 0.05 |

| Care (e) | You see a girl laughing at another student forgetting her lines at a school play. | 0.56 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.01 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Care (e) | You see a woman commenting out loud about how fat another woman looks in her jeans. | 0.80 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.04 |

| Care (e) | You see a man quickly canceling a blind date as soon as he sees the woman. | 0.50 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.15 | −0.04 |

| Care (e) | You see a boy telling a woman that she looks just like her overweight bulldog. | 0.64 | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.02 |

| Care (e) | You see a girl laughing when she realizes her friend’s dad is the janitor. | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.16 | 0.01 |

| Care (e) | You see a man snickering as he passes by a cancer patient with a bald head. | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.13 | −0.34 | 0.03 |

| Care (e) | You see a girl saying that another girl is too ugly to be a varsity cheerleader. | 0.69 | 0.16 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.14 | −0.11 | 0.07 | −0.16 | 0.02 |

| Care (e) | You see a teenage girl openly staring at a disfigured woman as she walks past. | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.06 |

| Care (e) | You see a boy making fun of his brother for getting dumped by his girlfriend. | 0.57 | 0.27 | 0.05 | −0.13 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.20 | 0.04 |

| Care (e) | You see a man loudly telling his wife that the dinner she cooked tastes awful. | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.07 |

| Care (e) | You see a man telling a woman that her painting looks like it was done by children. | 0.56 | 0.10 | 0.15 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.03 |

| Care (e) | You see a woman clearly avoiding sitting next to an obese woman on the bus. | 0.44 | 0.12 | 0.05 | −0.18 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.03 |

| Care (e) | You see a girl telling a boy that his older brother is much more attractive than him. | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.16 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.01 |

| Care (e) | You see a girl telling her classmate that she looks like she has gained weight. | 0.60 | 0.02 | 0.10 | −0.18 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.10 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| Care (e) | You see a man laughing at a disabled co-worker while at an office softball game. | 0.41 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.14 | −0.30 | 0.05 |

| Care (p,a) | You see a woman swerving her car in order to intentionally run over a squirrel. | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.15 | 0.49 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.05 |

| Care (p,a) | You see a woman throwing her cat across the room for scratching the furniture. | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Care (p,a) | You see someone leaving his dog outside in the rain after it dug in the trash. | −0.05 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.23 | 0.75 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.19 | 0.08 |

| Care (p,a) | You see a boy throwing rocks at cows that are grazing in the local pasture. | 0.11 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.76 | −0.17 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| Care (p,a) | You see a zoo trainer jabbing a dolphin to get it to entertain his customers. | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.79 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

| Care (p,a) | You see a man lashing his pony with a whip for breaking loose from its pen. | −0.15 | −0.14 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.77 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| Care (p,a) | You see a girl shooting geese repeatedly with a pellet gun out in the woods. | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.74 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Care (p,a) | You see a woman snatching away her dog’s food for making a mess in the living room. | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.65 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.33 | −0.08 |

| Care (p,a) | You see a boy setting a series of traps to kill stray cats in his neighborhood. | 0.08 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.12 | 0.72 | −0.07 | 0.12 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| Care (p,h) | You see a woman throwing a stapler at her colleague who is snoring during her talk. | 0.20 | 0.26 | −0.13 | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.11 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.30 |

| Care (p,h) | You see a girl throwing her hot coffee on a woman who is dating her ex-boyfriend | 0.18 | 0.09 | −0.10 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.20 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.33 |

| Care (p,h) | You see a boy placing a thumbtack sticking up on the chair of another student. | 0.15 | 0.23 | −0.08 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| Care (p,h) | You see a woman slapping another woman who she is arguing with in the parking lot. | 0.33 | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.19 | 0.37 |

| Care (p,h) | You see a teacher hitting a student’s hand with a ruler for falling asleep in class. | 0.09 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.41 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.11 |

| Care (p,h) | You see a woman spanking her child with a spatula for getting bad grades in school. | 0.12 | −0.07 | −0.15 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.08 |

| Care (p,h) | You see a wife hitting her husband on the side of his head for coming home late. | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.21 | −0.05 | 0.13 | 0.39 |

| Fairness | You see a student copying a classmate’s answer sheet on a makeup final exam. | −0.12 | 0.27 | −0.03 | 0.69 | 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| Fairness | You see a runner taking a shortcut on the course during the marathon in order to win. | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.54 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.08 |

| Fairness | You see a tenant bribing a landlord to be the first to get their apartment repainted. | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.05 | −0.08 | −0.12 | 0.22 | 0.10 |

| Fairness | You see a soccer player pretending to be seriously fouled by an opposing player. | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.25 | −0.06 |

| Fairness | You see someone cheating in a card game while playing with a group of strangers. | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.65 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| Fairness | You see a referee intentionally making bad calls that help his favored team win. | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.71 | −0.06 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.01 |

| Fairness | You see a manager taking half the doughnuts from a box, leaving little for others. | −0.01 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.16 | −0.17 |

| Fairness | You see a judge taking on a criminal case although he is friends with the defendant. | 0.00 | −0.35 | 0.24 | 0.39 | −0.05 | 0.17 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.08 |

| Fairness | You see a student getting an A on a group project when he didn’t do his part. | 0.10 | 0.38 | −0.03 | 0.32 | 0.12 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.02 |

| Fairness | You see an employee lying about how many hours she worked during the week. | −0.03 | 0.20 | −0.08 | 0.67 | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.07 |

| Fairness | You see a woman getting hired only because her father is close friends with the boss. | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.04 |

| Fairness | You see a girl asking for allowance even though her brother did her chores for her. | 0.14 | 0.36 | −0.03 | 0.45 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.15 | −0.14 |

| Fairness | You see a girl taking all the Halloween candy from a bowl, leaving none for others. | 0.15 | 0.40 | −0.01 | 0.23 | 0.13 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.09 |

| Fairness | You see a boy skipping to the front of the line because his friend is an employee. | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.18 | −0.04 |

| Fairness | You see a woman lying about the number of vacation days she has taken at work. | −0.04 | 0.22 | −0.04 | 0.51 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.10 |

| Fairness | You see a professor giving a bad grade to a student just because he dislikes him. | 0.13 | 0.13 | −0.09 | 0.39 | 0.13 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.23 | −0.06 |

| Fairness | You see a politician using federal tax dollars to build an extension on his home. | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.18 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.23 | 0.05 |

| Liberty | You see a man telling his fiance that she has to switch to his political party. | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.06 |

| Liberty | You see a father requiring his son to become a commercial airline pilot like him. | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.13 | 0.95 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.09 |

| Liberty | You see a man blocking his wife from leaving home or interacting with others. | 0.17 | −0.12 | −0.02 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.14 | −0.03 | −0.09 | 0.08 |

| Liberty | You see a manager coercing her employees into eating at her brother’s diner. | −0.14 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.06 |

| Liberty | You see a man telling his girlfriend that she must convert to his religion. | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.18 | 0.50 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.02 |

| Liberty | You see a mother telling her son that she is going to choose all of his friends. | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.06 |

| Liberty | You see a man forbidding his wife to wear clothing that he has not first approved. | 0.19 | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.27 | 0.46 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Liberty | You see a boss ordering an employee to revoke his citizenship in his home country. | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.27 | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.06 |

| Liberty | You see a boss pressuring employees to buy goods from her family’s general store. | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.11 | −0.05 |

| Liberty | You see a woman pressuring her daughter to become a famous evening news anchor. | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.00 | −0.14 | −0.05 | 0.73 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Liberty | You see a public leader on TV trying to ban the wearing of hooded sweatshirts. | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.17 | 0.34 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.26 |

| Liberty | You see a mother forcing her daughter to enroll as a pre-med student in college. | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.04 | −0.11 | −0.09 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| Liberty | You see a father requiring his son to take up the family restaurant business. | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.10 | 0.88 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| Liberty | You see a teacher ordering a student to get a normal haircut before coming to class. | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.26 | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.18 |

| Liberty | You see a teenager at a cafeteria forcing a younger student to pay for her lunch. | 0.13 | 0.22 | −0.11 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.03 |

| Liberty | You see a mayor trying to ban people from hugging and kissing in public in his city. | 0.24 | −0.08 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.18 | −0.08 | −0.12 | −0.08 |

| Liberty | You see a pastor banning his congregants from wearing bright colors in the church. | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.20 |

| Authority | You see a girl ignoring her father’s orders by taking the car after her curfew. | −0.04 | 0.60 | −0.04 | 0.26 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Authority | You see a woman refusing to stand when the judge walks into the courtroom. | −0.04 | 0.54 | 0.36 | −0.16 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.13 |

| Authority | You see a girl repeatedly interrupting her teacher as he explains a new concept. | 0.12 | 0.61 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| Authority | You see a woman spray painting graffiti across the steps of the local courthouse. | −0.11 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.14 | −0.11 | 0.42 |

| Authority | You see an intern disobeying an order to dress professionally and comb his hair. | −0.13 | 0.65 | 0.19 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Authority | You see a teenage girl coming home late and ignoring her parents’ strict curfew. | −0.08 | 0.61 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.01 |

| Authority | You see a boy spray-painting anarchy symbols on the side of the police station. | −0.05 | 0.57 | −0.01 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.11 | −0.10 | 0.38 |

| Authority | You see an employee trying to undermine all of her boss’ ideas in front of others. | 0.09 | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.17 |

| Authority | You see a player publicly yelling at his soccer coach during a playoff game. | 0.07 | 0.44 | 0.12 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.11 |

| Authority | You see a man secretly watching sports on his cell phone during a pastor’s sermon. | 0.11 | 0.51 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.03 | 0.21 | 0.07 | −0.05 |

| Authority | You see a boy turning up the TV as his father talks about his military service. | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | −0.15 |

| Authority | You see a teaching assistant talking back to the teacher in front of the classrom. | 0.08 | 0.54 | 0.19 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Authority | You see a staff member talking loudly and interrupting the mayor’s speech to the public. | 0.19 | 0.54 | 0.26 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.10 | −0.14 | 0.07 |

| Authority | You see a group of women having a long and loud conversation during a church sermon. | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.14 | −0.14 | −0.02 |

| Authority | You see a man turn his back and walk away while his boss questions his work. | −0.01 | 0.60 | 0.16 | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Authority | You see a student stating that her professor is a fool during an afternoon class. | 0.24 | 0.50 | 0.13 | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.20 | 0.10 |

| Authority | You see a star player ignoring her coach’s order to come to the bench during a game. | 0.00 | 0.60 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.14 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Loyalty | You see an employee joking with competitors about how bad his company did last year. | 0.11 | 0.28 | 0.43 | −0.11 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| Loyalty | You see a coach celebrating with the opposing team’s players who just won the game. | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.74 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.04 |

| Loyalty | You see a former US General saying publicly he would never buy any American product. | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.60 | 0.09 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| Loyalty | You see a mayor saying that the neighboring town is a much better town. | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.63 | −0.07 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.12 | −0.04 |

| Loyalty | You see the US Ambassador joking in Great Britain about the stupidity of Americans. | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.11 | 0.15 |

| Loyalty | You see a man leaving his family business to go work for their main competitor. | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.45 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.10 | −0.21 |

| Loyalty | You see a teacher publicly saying she hopes another school wins the math contest. | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.62 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.01 |

| Loyalty | You see a head cheerleader booing her high school’s team during a homecoming game. | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.13 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Loyalty | You see the class president saying on TV that her rival college is a better school. | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.68 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| Loyalty | You see a Hollywood star agreeing with a foreign dictator’s denunciation of the US. | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Loyalty | You see a college president singing a rival school’s fight song during a pep rally. | −0.05 | 0.17 | 0.69 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.12 |

| Loyalty | You see a man secretly voting against his wife in a local beauty pageant. | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.36 | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.12 | 0.06 | −0.17 |

| Loyalty | You see an American telling foreigners that the US is an evil force in the world. | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.47 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.15 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Loyalty | You see the coach’s wife sponsoring a bake sale for her husband’s rival team. | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.77 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.05 |

| Loyalty | You see a former Secretary of State publicly giving up his citizenship to the US. | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.60 | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.17 |

| Loyalty | You see a US swimmer cheering as a Chinese foe beats his teammate to win the gold. | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.62 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.00 |

| Sanctity | You see a man having sex with a frozen chicken before cooking it for dinner. | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.10 | 0.69 | −0.03 | −0.07 |

| Sanctity | You see a family eating the carcass of their pet dog that had been run over. | −0.01 | −0.14 | 0.10 | −0.03 | 0.33 | −0.12 | 0.55 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| Sanctity | You see a drunk elderly man offering to have oral sex with anyone in the bar. | 0.05 | 0.19 | −0.08 | 0.00 | −0.16 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Sanctity | You see a teenager urinating in the wave pool at a crowded amusement park. | −0.04 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.25 | −0.01 | 0.13 | −0.07 | 0.03 |

| Sanctity | You see a man in a bar using his phone to watch people having sex with animals. | 0.19 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.59 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Sanctity | You see a teenage male in a dorm bathroom secretly using a stranger’s toothbrush. | −0.13 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.11 | −0.09 | −0.15 |

| Sanctity | You see a woman having intimate relations with a recently deceased loved one. | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.44 | −0.08 | 0.11 |

| Sanctity | You see a homosexual in a gay bar offering sex to anyone who buys him a drink. | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.12 | −0.18 | 0.07 | 0.69 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Sanctity | You see an employee at a morgue eating his pepperoni pizza off of a dead body. | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.49 | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| Sanctity | You see a girl and her sister making out with each other just for practice. | −0.08 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Sanctity | You see a story about a remote tribe eating the flesh of their deceased members. | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.07 | −0.15 | 0.17 | −0.08 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 0.13 |

| Sanctity | You see a woman burping and farting loudly while eating at a fast food truck. | 0.06 | 0.41 | 0.14 | −0.11 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.23 | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| Sanctity | You see a man searching through the trash to find women’s discarded underwear. | 0.14 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.61 | 0.01 | −0.10 |

| Sanctity | You see two first cousins getting married to each other in an elaborate wedding. | −0.16 | 0.08 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.57 | −0.06 | −0.10 |

| Sanctity | You see a single man ordering an inflatable sex doll that looks like his secretary. | 0.16 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.16 | 0.00 | 0.52 | 0.24 | −0.04 |

| Sanctity | You see a very drunk woman making out with multiple strangers on the city bus. | −0.03 | 0.40 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| Sanctity | You see a college student drinking until she vomits on herself and falls asleep. | 0.07 | 0.39 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

Note:factor loadings ≥ .4 are shown in bold. Factor loadings < .3 are shown in gray.

In the first factor, all 16 Care scenarios representing emotional harm have factor loadings greater than .4. However, none of the Care scenarios representing physical harm load onto this factor, with the exception of one modest loading (.33). This scenario involves a slapping a woman during an argument, which may have been construed as emotionally harmful in addition to being physically harmful. All nine of the Care scenarios involving harm to animals load strongly onto the fifth factor, and three of the seven scenarios involving harm to humans load onto this factor as well, though the factor loadings are less strong. The remaining three Care scenarios involving harm to humans load weakly onto the ninth factor along with two Authority items. Given the weak and inconsistent loadings on this ninth factor (only one scenario has a factor loading greater than .4), it likely is not substantively meaningful. Overall, the findings regarding our Care scenarios support research finding that moral violations may be processed differently when they involve bodily harm (Heekeren et al., 2005), though we did not find a clear separation between physical harm to humans and animals.

In the second factor, all 17 Authority scenarios have factor loadings greater than .4, though one has a modest cross-loading (.36) on Loyalty (refusing to stand for a judge). However, four Fairness scenarios and four Sanctity scenarios also have loadings greater than .3 on this factor. 14 of 17 Fairness scenarios load onto the fourth factor with loadings greater than .3 (10 greater than .4), although two of these scenarios cross-load onto the Authority factor. Of the four total Fairness scenarios that load onto Authority, three involve children or students deceiving an authority figure and one involves a greedy manager.

Turning to the third factor, all 16 Loyalty scenarios have factor loadings greater than 0.3. Overall, we find clear separation between the Authority and Loyalty foundations.

11 of the 17 Liberty scenarios load onto the sixth factor, while no other scenarios load onto this factor. Of the remaining six scenarios, one loads weakly onto Fairness, and one loads weakly onto the eighth factor. Given that only two scenarios (Liberty and Care – animals) load on the eighth factor, it does not appear to be substantively meaningful. Our results regarding Liberty provide some initial support for this new foundation. However, it should be noted that all of the scenarios with factor loadings greater than .4 involved either coercion of children on the part of their parents, or coercion of a woman by a husband or boyfriend. The scenarios involving coercion by a teacher or boss did not load strongly onto the factor. Thus, this factor only seems to be picking up a particular aspect of Liberty involving coercion within family units.

Finally, 14 of the 17 Sanctity scenarios load onto the seventh factor. However, several of these scenarios modestly cross-load onto Authority, though it is not clear what features these scenarios share with Authority. Finally, one of the Sanctity scenarios involving eating a pet dog cross-loads weakly onto the physical harm factor, which includes harm to animals. Overall, the Sanctity scenarios form a coherent factor, including both sexual and non-sexual aspects of physical disgust.

In summary, our findings from the exploratory factor analysis show strong support for the expected divisions within the moral domain. We uncovered factors associated with each of the original moral foundations, as well as the newer Liberty foundation. We also found evidence of a division within the Care foundation depending on whether the violation involves emotional or physical harm. However, at this time it is unclear whether this latter aspect of the Care foundation should be interpreted as primarily representing harm to non-human animals, or as more broadly representing physical harm.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Since prior research provides strong predictions about the factor structure of moral judgment, we also analyzed our data using a confirmatory factor analysis. We estimated an eight-factor model consisting of Care – emotional, Care – physical-human, Care – physical-animal, Fairness, Liberty, Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity. Our eight-factor model fit the data well (χ2(6,526) = 12,616.71; RMSEA = .047). We also estimated several simpler models for comparison (shown in Table 3) and in each case our hypothesized model provided a better fit to the data as judged by improvements in the RMSEA and AIC, though the improvements are modest in moving from the seven-factor models to the eight-factor model. Overall, the results provide support for our hypothesized model.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis of wrongness ratings

| # of Factors | Description | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | 90 % C.I. | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Individualizing and binding | 16,156.29 | 6, 553 | 2.47 | .059 | .058, .061 | 129,997.09 |

| 6 | Original MFT, plus Liberty | 13,607.23 | 6, 539 | 2.08 | .051 | .050, .052 | 127,476.03 |

| 7 | Division of physical and emotional harm | 12,933.23 | 6, 533 | 1.98 | .049 | .047, .050 | 126,814.03 |

| 7 | Division of human and animal harm | 12,893.93 | 6, 533 | 1.97 | .048 | .047, .050 | 126,774.73 |

| 8 | Division of emotional, physical, animal harm | 12,616.71 | 6, 526 | 1.93 | .047 | .046, .049 | 126,511.51 |

MFT, moral foundations theory. Boldface indicates the best-fitting model.

Criterion validity

We next demonstrate the criterion validity of our new scales by comparing them to two existing measures of the moral foundations—the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ) and the Moral Foundations Sacredness Scale (MFSS). Because the EFA demonstrated that several of the scenarios did not load on the expected factors, we utilize the seven factor scores from the EFA reported above. All other scales were standardized (correlations shown in Table 8 in the Appendix). Each factor of the MFVs was predicted as a function of each scale of the MFQ (Table 4, top panel) and the MFSS (Table 4, bottom panel) using OLS regression models.5 Focusing first on the MFQ, in each case the MFQ criterion is a strong predictor of the MFVs subscale (βs = .24–.47; all ps < .001). Moreover, the criterion scale is always the strongest predictor, although we do not have the statistical power to distinguish between all of these coefficients. Although the MFQ does not contain a Liberty subscale, we examine the predictive power of the original five foundations included in the MFQ. We find that the MFQ Fairness scale is a strong predictor of Liberty (β = .39, t(406) = 6.14, p < .001), followed by Care (β = .15, t(406) = 2.42, p = .02).

Table 4.

Predicting scores for the moral foundations vignettes (MFV) with existing moral foundations scales

| Care (e) | Care (p) | Fairness | Liberty | Loyalty | Authority | Sanctity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFQ | |||||||

| Care |

.34*** (.06) |

.47*** (.06) |

.08 (.06) |

.15* (.06) |

.06 (.06) |

−.06 (.06) |

.14* (.06) |

| Fairness | .21** (.06) |

.23*** (.06) |

.34*** (.06) |

.39*** (.06) |

.09 (.06) |

.18* (.06) |

−.03 (.06) |

| Loyalty | .15* (.06) |

−.05 (.06) |

.00 (.07) |

.09 (.07) |

.41*** (.06) |

.22*** (.06) |

.16** (.06) |

| Authority | −.03 (.07) |

−.04 (.07) |

.05 (.07) |

−.07 (.07) |

.10 (.07) |

.24*** (.07) |

.10 (.06) |

| Sanctity | .05 (.06) |

−.10 (.06) |

.06 (.07) |

−.10 (.06) |

.05 (.06) |

.14* (.06) |

.37*** (.06) |

| Constant | −.01 (.04) |

−.04 (.04) |

−.01 (.04) |

−.01 (.04) |

.03 (.04) |

.03 (.04) |

.03 (.04) |

| R2 | .30 | .30 | .17 | .20 | .34 | .33 | .38 |

| MFSS | |||||||

| Care | .17* (.09) |

.57*** (.08) |

.15 (.08) |

.22* (.09) | −.22** (.09) |

−.25** (.08) |

.06 (.08) |

| Fairness | .10 (.09) |

−.02 (.08) |

.42*** (.08) |

.06 (.09) |

−.11 (.09) |

.13 (.08) |

−.04 (.08) |

| Loyalty | .04 (.08) |

−.08 (.08) |

.05 (.08) |

.04 (.08) |

.35*** (.08) |

.12 (.08) |

.11 (.08) |

| Authority | .09 (.07) |

−.08 (.07) |

−.19** (.07) |

−.08 (.07) |

.03 (.07) |

.20** (.07) |

.04 (.07) |

| Sanctity | −.02 (.08) |

−.05 (.07) |

.07 (.04) |

−.03 (.08) |

.14 (.08) |

.15* (.07) |

.26*** (.07) |

| Constant | −.04 (.05) |

−.08 (.05) |

−.07 (.04) |

−.04 (.05) |

.00 (.05) |

.00 (.05) |

−.04 (.04) |

| R2 | .08 | .13 | .15 | .03 | .09 | .14 | .12 |

Cell entries show ordinary least-squares coefficients for the Moral Foundation Questionnaire (MFQ, top) and Moral Foundations Sacredness Scale (MFSS, bottom) foundations predicting MFV scales. All scales are standardized. The largest coefficient in each row is bolded. Note that there are no existing criterion variables for the Liberty foundation. “Care (e)” refers to the emotional harm factor, and “Care (p)” refers to the physical harm factor.

p < .05,

p < .01,