Abstract

Graves’ disease (GD) is an autoimmune oligogenic disorder with a strong hereditary component. Several GD susceptibility genes have been identified and confirmed during the last two decades. However, there are very few studies that evaluated susceptibility genes for GD in specific geographic subsets. Previously, we mapped a new locus on chromosome 3q that was unique to GD families of Italian origin. In the present study, we used association analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) at the 3q locus in a cohort of GD patients of Italian origin in order to prioritize the best candidates among the known genes in this locus to choose the one(s) best supported by the association. DNA samples were genotyped using the Illumina GoldenGate genotyping assay analyzing 690 SNP in the linked 3q locus covering all 124 linkage disequilibrium blocks in this locus. Candidate non-HLA (human-leukocyte-antigen) genes previously reported to be associated with GD and/or other autoimmune disorders were analyzed separately. Three SNPs in the 3q locus showed a nominal association (p < 0.05): rs13097181, rs763313, and rs6792646. Albeit these could not be further validated by multiple comparison correction, we were prioritizing candidate genes at a locus already known to harbor a GD-related gene, not hypothesis testing. Moreover, we found significant associations with the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) gene, the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) gene, and the thyroglobulin (TG) gene. In conclusion, we identified three SNPs on chromosome 3q that may map a new GD susceptibility gene in this region which is unique to the Italian population. Furthermore, we confirmed that the TSHR, the CTLA-4, and the TG genes are associated with GD in Italians. Our findings highlight the influence of ethnicity and geographic variations on the genetic susceptibility to GD.

Keywords: Graves’ disease, thyroid diseases, genetic predisposition to disease, SNP association study, Italian patients

Introduction

Graves’ disease (GD) is one of the most common autoimmune endocrine disorders characterized by goiter, hyperthyroidism and, in 10–25% of patients, ophthalmopathy (1, 2). GD is an antibody-mediated autoimmune disease, in which the pathogenic antibodies stimulate the thyroid-stimulating hormone (thyrotropin, TSH) receptor resulting in the clinical syndrome of goiter and hyperthyroidism. The pathogenesis of GD involves breakdown of central and peripheral tolerance, infiltration of the thyroid with thyroid-directed T-cells that escaped tolerance, and activation of B-cells to secrete TSH receptor (TSHR) stimulating antibodies (3).

While the exact etiology of GD has not been pinpointed yet, accumulating data, mainly obtained in twin studies, support a solid genetic predisposition to the disease, although the penetrance of the genetic determinants is about 22–35% (based on monozygotic twin concordance rates) (4–6). Several GD susceptibility genes have been identified and confirmed through linkage and association studies during the last three decades, including immune regulatory genes HLA-DR, (human leukocyte antigen – D related) cluster of differentiation 40 (CD40), CTLA-4, protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22 (PTPN22), interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain (CD25), and thyroid-specific genes TSHR and TG (7). Moreover, several susceptibility genes for Graves’ ophthalmopathy have been proposed over the years based on small case–control association studies. These include CTLA-4, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (8), insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) (9), suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) (10), thyroid peroxidase (TPO) (11), calsequestrin 1 (CASQ1) (12), cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CYR61), zinc finger protein 36 C3H type homog mouse (ZFP36), and stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase (SCD) (13). However, none of the Graves’ ophthalmopathy specific genes have been confirmed.

Ethnicity and geographic variations influence the genetic susceptibility to GD. Previous studies demonstrated in Caucasian populations a positive and a negative association of GD with the serologically defined HLA DR3 and DR5 groups, respectively (14, 15). HLA-DRB1*0301 gave the highest positive predictive value for GD (15). HLA genes have been shown to be associated with GD in non-Caucasian populations as well, though the associated alleles were different from those observed in Caucasians (7, 16–18). For instance, the HLA-DRB1*0405/DQB1*0401 and the DRB3*020/DQA1*0501 haplotypes have been directly linked to GD in Asians (19) and in African-American (20) subjects, respectively. Notably, ethnic influences have been reported also for non-MHC genes; indeed linkage analysis in Caucasian families from different geographic regions showed different influences of the CTLA-4 gene on GD development (21, 22), suggesting that even within the same ethnic group, geographic variations can have a strong effect on susceptibility to disease. Similarly, a recent study indicated that genetic polymorphisms at CD25, a gene that is associated with GD in Caucasians, do not exert a significant genetic effect on the development of GD in the Chinese Han population (23). Also, significant ethnic differences in the distribution of two germline TSHR polymorphisms (P52T and D727E) were found among the Chinese, Malays, and Indians (24).

Intriguingly, epidemiological surveys from various, mostly iodine sufficient, populations have shown a relatively comparable incidence of GD across Caucasian populations in different geographic regions (approximately 20–25/100,000/year). The comparable prevalence and incidence of GD in geographically distinct Caucasian populations may indicate that these populations share at least some of their susceptibility genes for GD, albeit unique GD genes for different populations must exist too (25). Nevertheless, there are very few studies that analyzed susceptibility genes for GD in specific geographic subsets of Caucasian GD patients. We have previously performed linkage analyses in a large dataset of multiplex GD families. Within our large dataset of GD families, an Italian subset of GD families did not show linkage to the CD40 gene/locus on chromosome 20q in contrast to all other Caucasian populations we studied. Moreover, we mapped a new locus on chromosome 3q that was unique to the Italian subset of our GD families (26). These data suggest that there are unique susceptibility gene/loci within Caucasian GD patients, as determined by our subset of Italian GD families, and that distinct genes predispose to GD in different subsets of patients.

Our previous results demonstrate the importance of identifying subsets of patients within large datasets in order to map genes that may be subset-specific. Therefore, the goal of the present study was to fine map the 3q locus and evaluate known GD susceptibility genes in a cohort of GD patients of Italian origin.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

The project was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. We analyzed Caucasian GD patients of Italian origin. GD was diagnosed by (1) documented clinical and biochemical hyperthyroidism requiring treatment and (2) presence of TSH receptor antibodies and/or diffusely increase 131I uptake in the thyroid gland.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from whole blood using the Puregene kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). DNA samples were genotyped using the Illumina GoldenGate genotyping assay as previously described (27). The GoldenGate single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping platform uses a discriminatory DNA polymerase and ligase to interrogate many SNPs simultaneously. The protocol is automated allowing high throughput and minimal errors. The GoldenGate genotyping assay utilized the BeadArray Reader. The GoldenGate assays were designed to analyze SNPs both in the linked locus on chromosome 3 and in a panel of GD candidate genes.

Fine Mapping of the Chromosome 3q Locus

The chromosome 3q locus spans about 14 Mb and was fine mapped using a panel of 690 SNPs. Since the linkage analysis showed that there was a gene in the region, our goal in association mapping was to prioritize the best candidates among the known genes in this locus to choose the one(s) best supported by the association. Markers for fine mapping 3q were selected from the Illumina Infinium Human1M BeadChip panel leveraging the pre-selection by Illumina of markers focused on haplotype tagging and maximal allele frequency in the CEU population. The SNPs selected were sufficient to capture all alleles with an r2 > 0.8. The mean max r2 for our SNPs was 0.987. Therefore, our 690 SNPs gave more than sufficient coverage of the 3q locus.

Case–control association analyses for markers within the 3q locus were performed using the UNPHASED computer package.1 UNPHASED (28, 29) is a suite of programs for association analysis of multilocus haplotypes from unphased genotype data. We used the Cocaphase program (within the UNPHASED package) for case–control association analyses performing the χ2 test on all 690 SNPs simultaneously. The odds ratio (OR) was calculated by the method of Woolf (30).

Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis was performed for the 3q locus using the Haploview program2 using SNP genotypes from the HapMap database (31). Haplotype analysis and haplotype association analysis of SNPs rs13097181, rs7633131, and 6792646 was performed with Haploview using our Italian GD and Italian controls genotypes.

Candidate Gene Analysis

Non-HLA genes that have been previously reported to be associated with GD and/or other autoimmune disorders were analyzed separately using the χ2 test. These candidate genes included TSHR, TG, CTLA-4, CD40, interleukin 23 receptor (IL23R), CD25, PTPN22, forkhead box P3 (FOXP3), interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5), and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) genes (32–37).

Power Calculations

Power calculations were performed using the CDC simulation software (Epi-Info, 7.1.3.3, CDC, Atlanta) (38). We assumed the population frequency of the susceptibility SNP allele to be ≥10% since we tested only common variants, and we used the gamete numbers since we performed allelic associations (39). The power calculations demonstrated that our dataset of 333 GD patients (666 chromosomes) and 117 controls (234 chromosomes) will give the study 80% power to detect a difference between the patients and the controls resulting in ORs of ≥2.0 with an alpha of 0.05. Therefore, our study was sufficiently powered to detect functionally significant differences between patients and controls.

Results

Characteristics of the Italian GD Population

We studied 333 Caucasian patients with GD of Italian origin. The average age at diagnosis was 40.0 ± 13.8 years (range 13–75 years), and there were 249 female and 84 male patients. The average age at ascertainment was 47.1 ± 13.7, and the average disease duration was 7.1 years. Additionally, 180 patients (54%) had goiter, 154 patients (46%) had Graves’ ophthalmopathy, and in 45 patients (14%), the ophthalmopathy status could not be confirmed. Control individuals of Italian origin (n = 117) had normal thyroid function, were negative for thyroid autoantibodies, and had no personal or family history of thyroid disease. There were 64 (55%) women and 53 men (45%). They were all over 18 years of age. However, the precise age at ascertainment was not available for all the controls.

Fine Mapping of the Chromosome 3q Locus and Haplotype Analysis

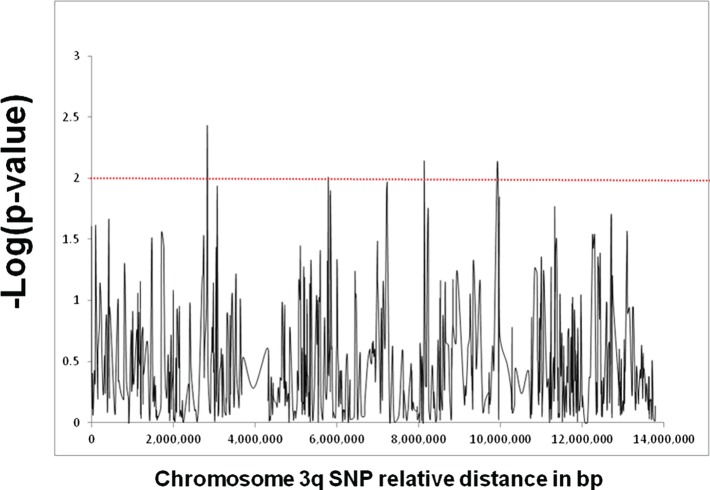

Figure 1 shows the results of association analyses of the 690 SNPs used to fine map the chromosome 3q locus that is linked with GD in patients of Italian origin. Three SNPs showed a significant association: rs13097181 (p = 3.7 × 10−3, OR: 2.0), rs7633131 (p = 7.7 × 10−3, OR: 1.7), and rs6792646 (p = 7.8 × 10−3, OR: 1.5). LD analysis showed that the 3q locus contained 124 LD blocks. If we were testing the hypothesis that there is a GD gene in the region, it would have been necessary to correct for multiple testing which would make the associations not significant. However, we were not testing the hypothesis of a GD gene in this locus. Rather our goal was to prioritize candidate genes at a locus already known to harbor a GD-related gene, and the p-values were only used to prioritize.

Figure 1.

Fine mapping analysis of the locus on chromosome 3q that showed strong linkage with GD in our subset of Italian GD families. The locus spans approximately 14 Mb and was fine mapped using a panel of 690 informative SNPs. The X-axis shows the distance in base pair between the SNPs and the Y-axis shows the −log(p-value) as computed by the UNPHASED program. The red line corresponds to a p-value of 0.01. Three SNPs (rs13097181, rs7633131, and rs6792646) showed significant association with p-values <0.01.

Haplotype analysis performed using Haploview for SNPs rs13097181, rs7633131, and rs6792646 (using either the genotypes in our cohort or the HapMap genotypes) revealed that there was no LD between these three SNPs due to the large distances between them (5.3 Mb between rs13097181 and rs7633131; 1.8 Mb between rs7633131 and rs6792646). Therefore, no haplotypes were identified for these three SNPS, and no combination of alleles of these three SNPs was associated with GD.

Candidate Gene Analysis

Several genes have been previously reported to be associated with GD in Caucasians and other ethnic groups (5, 40). We investigated a panel of genes previously shown to be linked with GD as well as genes associated with other autoimmune diseases (e.g., IRF5 and TLR4, see Table 1). Among the candidate genes tested, we found associations with the TSHR gene (p = 3.94 × 10−6), the CTLA-4 gene (p = 1 × 10−3), and the TG gene (p = 0.029).

Table 1.

Results of candidate gene analysis.

| Candidate gene | SNP | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| IL23R | rs2201841 | 0.622036 |

| IL23R | rs11209026 | 0.259565 |

| IL23R | rs10889677 | 0.786908 |

| PTPN22 | rs2476601 | 0.727479 |

| CTLA4 | rs231775 | 0.00106852 |

| CTLA4 | rs3087243 | 0.0303233 |

| IRF5 | rs4728142 | 0.45456 |

| IRF5 | rs10488631 | 0.769101 |

| IRF5 | rs12537284 | 0.56248 |

| Tg | rs180194 | 0.384458 |

| Tg | rs180223 | 0.624968 |

| Tg | rs2069550 | 0.692976 |

| Tg | rs853326 | 0.754905 |

| Tg | rs2069561 | 0.0292331 |

| Tg | rs2076740 | 0.182472 |

| Tg | rs2294024 | 0.214108 |

| TLR4 | rs4986790 | 0.736433 |

| TLR4 | rs4986791 | 0.163881 |

| CD25 | rs706778 | 0.0630883 |

| CD25 | rs3118470 | 0.52791 |

| CD25 | rs41295061 | 0.498702 |

| TSHR | rs179247 | 3.94E−06 |

| TSHR | rs3783948 | 0.00104205 |

| TSHR | rs12101255 | 0.0356936 |

| CD40 | rs1883832 | 0.464766 |

| CD40 | rs4810485 | 0.466903 |

| FOXP3 | rs6609857 | 0.743244 |

| FOXP3 | rs2294021 | 0.703636 |

| FOXP3 | rs2280883 | 0.747625 |

| FOXP3 | rs2232365 | 0.738291 |

| FOXP3 | rs3761549 | 0.496996 |

Genes in bold are significantly associated with GD.

Discussion

A strong hereditary component in the pathogenesis of GD has long been recognized (41, 42). The inheritance of GD is complex, involving multiple genes with variable penetrance, and environmental and epigenetic factors also play a critical role in the etiology of the disease (5, 43, 44). Previous studies have shown differences in genetic associations with GD in different ethnic groups; however, most of these studies compared Caucasian patients to Asian patients.

In the present study, we dissected the genetic susceptibility in GD patients of Italian origin via fine mapping the Italian GD locus on chromosome 3q and analyzing several known susceptibility genes for GD. We identified three SNPs on chromosome 3q that were associated with GD in Italian patients, and we demonstrated that the TSHR, the CTLA-4, and the TG genes are associated with GD in Italians. Our results are consistent with previous findings suggesting the existence of unique autoimmunity susceptibility genes in Caucasian populations of different geographic regions (26, 45). Indeed, Marron et al. have shown considerable variability in the association of CTLA-4 with type 1 diabetes among different Caucasian populations (46).

We tested 690 SNPs for association with GD at the 3q locus, a locus which a family study had previously been identified as containing a GD-related gene. Our goal in this study was not to identify a region containing disease-related gene but to prioritize which genes might be worth pursuing. Many of the 690 SNPs we typed shared LD blocks, meaning the association signals the SNPs produced were not independent of one another. The 3q locus that was fine mapped contained 124 LD blocks. Correcting for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction for 124 tests would make the p-values for the three associated SNPs become not significant. However, since we were within a locus that we already determined to be linked to the disease, interpreting the Bonferroni-corrected p-values with the same intent as for a GWAS would miss our goal of determining which genes would be the best ones to examine in the next step of identifying the disease-related gene. Ideally, stronger association signals (p-values) would be better but the decision to investigate a specific patient population limited the sample size. Nonetheless, the results do give us important information that can be used to prioritize the known genes best supported by our association study.

The SNP within the chromosome 3q locus showing the strongest association with GD in Italians (rs13097181) maps to an intergenic region between the EPHB1 gene (ephrin receptor B 1) and the KY gene (kyphoscoliosis peptidase). Notably, ephrin receptors make up the largest subgroup of the receptor tyrosine kinase family and are known to regulate T-cell activation, costimulation, and proliferation (47, 48), suggesting a potential functional role for EPHB1 in the context of GD pathogenesis. The potential role, if any, of the KY gene, generally involved in processes of muscle growth (49), in GD pathophysiology remains to be determined. The other two chromosome 3q SNPs that were associated with GD in our population are rs7633131 and rs6792646. rs7633131 is an intronic SNP within the CLSTN2 gene (calsyntenin 2), which does not affect the immune system or the thyroid (50). rs6792646 is an intergenic SNP located between the GRK7 (G protein-coupled receptor kinase 7) gene and the HMGN2P25 (high mobility group nucleosomal-binding domain 2 pseudogene 25) gene, two genes that do not seem to be functionally connected to GD (51, 52). Of course, the assumptions on potential mechanisms linking these genes to GD deserve further experimental validation. Nonetheless, disease-associated SNPs can also impact transcriptional mechanisms by modulating the binding of transcriptional factors or long-range interactions via genetic/epigenetic dysregulation (43, 53), eventually upregulating or downregulating gene transcription in order to generate a phenotype (54).

Genes that exert their effect early in the autoimmune response and control the breakdown in self-tolerance are strongly associated with GD. In the past two decades, several GD susceptibility genes have been identified and confirmed through linkage and association studies, including HLA-DRβ1-Arg74, CTLA-4, PTPN22, CD40, CD25, TG, and the TSHR gene (55). TG, in particular, is an important candidate gene for GD, indeed the best model of human autoimmune thyroiditis is induced by immunizing mice with TG (56). Interestingly, GD patients have increased numbers of circulating T cells and B cells that proliferate in response to stimulation with TG (57). Recently, a significant positive correlation has been reported between serum TG levels and the presence and severity of ophthalmopathy in patients with GD. In these patients, TG levels also correlated to serum titers of TSHR antibodies, indicating that not only TSHR but also TG may be released from the thyroid gland in the course of a thyroiditis and home to the orbit where they become targets of autoantibodies and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (58, 59).

Furthermore, several genetic studies have demonstrated an association between thyroid autoimmunity and gene polymorphisms of proteins and enzymes associated with vitamin D functions (60–62). Indeed, in animal models, vitamin D administration efficiently prevented the induction of experimental autoimmune thyroiditis (63). Moreover, taking into account human studies, a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was reported both in patients with chronic autoimmune thyroiditis and in those with GD (64).

Consistent with previous reports (5, 40), among the candidate genes we tested, we found significant associations with the TSHR, CTLA-4, and TG genes. The CTLA-4 gene had been previously implicated, in different ethnic groups, in diverse autoimmune disorders, including Addison’s disease (65), Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (66), Type 1 diabetes mellitus (22), multiple sclerosis (67), and GD (68). Of note, there was no significant association of GD with CD40 in our dataset, which is in agreement with our previous finding that CD40 was not linked with GD in a cohort of Italian families (69). Moreover, the TG SNP that is associated with GD in our Italian cohort is different than the one we previously identified in a cohort of North American Caucasian AITD patients, again underscoring the importance of ethnic variations in variants predisposing to GD.

The main limitation of our study is the relatively small size of our cohort. However, our cohort was ethnically homogenous, thereby increasing the power of our analysis.

In conclusion, we identified three SNPs on chromosome 3q that are associated with GD in Italian patients indicating potential GD susceptibility genes in this locus. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the TSHR, the CTLA-4, and the TG genes are associated with GD in Italians. Notably, there were no associations with CD40, CD25, and FOXP3. Our findings highlight the importance of ethnic variation in the association of different polymorphisms with GD even within the same candidate gene.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed significantly to the work, have read the manuscript, attest to the validity and legitimacy of the data and its interpretation, and agree to its submission.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants DK061659 and DK073681 from NIDDK. In addition, this material is based upon work supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, Hannon WH, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2002) 87(2):489–99. 10.1210/jcem.87.2.8182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. The epidemiology of Graves’ disease: evidence of a genetic and an environmental contribution. J Autoimmun (2010) 34(3):J307–13. 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies TF. Trauma and pressure explain the clinical presentation of the Graves’ disease triad. Thyroid (2000) 10(8):629–30. 10.1089/10507250050137680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brix TH, Christensen K, Holm NV, Harvald B, Hegedus L. A population-based study of Graves’ disease in Danish twins. Clin Endocrinol (1998) 48(4):397–400. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1998.00450.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marino M, Latrofa F, Menconi F, Chiovato L, Vitti P. Role of genetic and non-genetic factors in the etiology of Graves’ disease. J Endocrinol Invest (2015) 38(3):283–94. 10.1007/s40618-014-0214-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RS, Lombardi A, Hasham A, Greenberg DA, Gordon J, Concepcion E, et al. Genetic analysis in young-age-of-onset Graves’ disease reveals new susceptibility loci. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2014) 99(7):E1387–91. 10.1210/jc.2013-4358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson EM, Huber A, Tomer Y. The HLA gene complex in thyroid autoimmunity: from epidemiology to etiology. J Autoimmun (2008) 30(1–2):58–62. 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chng CL, Seah LL, Khoo DH. Ethnic differences in the clinical presentation of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab (2012) 26(3):249–58. 10.1016/j.beem.2011.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahn RS. Current Insights into the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Horm Metab Res (2015) 47(10):773–8. 10.1055/s-0035-1555762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan R, Yang J, Jiang P, Jin L, Ma J, Huang R, et al. Genetic variations in the SOCS3 gene in patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Pathol (2015) 68(6):448–52. 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kus A, Szymanski K, Peeters RP, Miskiewicz P, Porcu E, Pistis G, et al. The association of thyroid peroxidase antibody risk loci with susceptibility to and phenotype of Graves’ disease. Clin Endocrinol (2015) 83(4):556–62. 10.1111/cen.12640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lahooti H, Cultrone D, Edirimanne S, Walsh JP, Delbridge L, Cregan P, et al. Novel single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the calsequestrin-1 gene are associated with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Clin Ophthalmol (2015) 9:1731–40. 10.2147/OPTH.S87972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Planck T, Shahida B, Sjogren M, Groop L, Hallengren B, Lantz M. Association of BTG2, CYR61, ZFP36, and SCD gene polymorphisms with Graves’ disease and ophthalmopathy. Thyroid (2014) 24(7):1156–61. 10.1089/thy.2013.0654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farid NR, Sampson L, Noel EP, Barnard JM, Mandeville R, Larsen B, et al. A study of human leukocyte D locus related antigens in Graves’ disease. J Clin Invest (1979) 63(1):108–13. 10.1172/JCI109263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zamani M, Spaepen M, Bex M, Bouillon R, Cassiman JJ. Primary role of the HLA class II DRB1*0301 allele in Graves disease. Am J Med Genet (2000) 95(5):432–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katsuren E, Awata T, Matsumoto C, Yamamoto K. HLA class II alleles in Japanese patients with Graves’ disease: weak associations of HLA-DR and -DQ. Endocr J (1994) 41(6):599–603. 10.1507/endocrj.41.599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Trevino O, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Cutino-Moguel T, Hernandez-Martinez B, Rodriguez-Reyna TS, Ruiz-Morales JA, et al. HLA study on two Mexican Mestizo families with autoimmune thyroid disease. Autoimmunity (2002) 35(4):265–9. 10.1080/0891693021000010712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maciel LM, Rodrigues SS, Dibbern RS, Navarro PA, Donadi EA. Association of the HLA-DRB1*0301 and HLA-DQA1*0501 alleles with Graves’ disease in a population representing the gene contribution from several ethnic backgrounds. Thyroid (2001) 11(1):31–5. 10.1089/10507250150500630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto K, Maruyama H, Nishiyama M, Asaba K, Ikeda Y, Takao T, et al. Susceptibility alleles and haplotypes of human leukocyte antigen DRB1, DQA1, and DQB1 in autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type III in Japanese population. Horm Res (2005) 64(5):253–60. 10.1159/000089293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen QY, Nadell D, Zhang XY, Kukreja A, Huang YJ, Wise J, et al. The human leukocyte antigen HLA DRB3*020/DQA1*0501 haplotype is associated with Graves’ disease in African Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2000) 85(4):1545–9. 10.1210/jcem.85.4.6523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reveille JD. The genetic basis of autoantibody production. Autoimmun Rev (2006) 5(6):389–98. 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nistico L, Buzzetti R, Pritchard LE, Van der Auwera B, Giovannini C, Bosi E, et al. The CTLA-4 gene region of chromosome 2q33 is linked to, and associated with, type 1 diabetes. Belgian diabetes registry. Hum Mol Genet (1996) 5(7):1075–80. 10.1093/hmg/5.7.1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song ZY, Liu W, Xue LQ, Pan CM, Wang HN, Gu ZH, et al. Dense mapping of IL2RA shows no association with Graves’ disease in Chinese Han population. Clin Endocrinol (2013) 79(2):267–74. 10.1111/cen.12115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho SC, Goh SS, Khoo DH. Association of Graves’ disease with intragenic polymorphism of the thyrotropin receptor gene in a cohort of Singapore patients of multi-ethnic origins. Thyroid (2003) 13(6):523–8. 10.1089/105072503322238773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villanueva R, Tomer Y, Greenberg DA, Mao C, Concepcion ES, Tucci S, et al. Autoimmune thyroid disease susceptibility loci in a large Chinese family. Clin Endocrinol (2002) 56(1):45–51. 10.1046/j0300-0664.2001.01429.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomer Y, Menconi F, Davies TF, Barbesino G, Rocchi R, Pinchera A, et al. Dissecting genetic heterogeneity in autoimmune thyroid diseases by subset analysis. J Autoimmun (2007) 29(2–3):69–77. 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomer Y, Hasham A, Davies TF, Stefan M, Concepcion E, Keddache M, et al. Fine mapping of loci linked to autoimmune thyroid disease identifies novel susceptibility genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2013) 98(1):E144–52. 10.1210/jc.2012-2408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudbridge F. Likelihood-based association analysis for nuclear families and unrelated subjects with missing genotype data. Hum Hered (2008) 66(2):87–98. 10.1159/000119108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishima H, Lidral AC, Ni J. Application of the Linux cluster for exhaustive window haplotype analysis using the FBAT and unphased programs. BMC Bioinformatics (2008) 9(Suppl 6):S10. 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S6-S10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woolf B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann Hum Genet (1955) 19(4):251–3. 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1955.tb01348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics (2005) 21(2):263–5. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brand OJ, Lowe CE, Heward JM, Franklyn JA, Cooper JD, Todd JA, et al. Association of the interleukin-2 receptor alpha (IL-2Ralpha)/CD25 gene region with Graves’ disease using a multilocus test and tag SNPs. Clin Endocrinol (2007) 66(4):508–12. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inoue N, Watanabe M, Yamada H, Takemura K, Hayashi F, Yamakawa N, et al. Associations between autoimmune thyroid disease prognosis and functional polymorphisms of susceptibility genes, CTLA4, PTPN22, CD40, FCRL3, and ZFAT, previously revealed in genome-wide association studies. J Clin Immunol (2012) 32(6):1243–52. 10.1007/s10875-012-9721-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simmonds MJ, Brand OJ, Barrett JC, Newby PR, Franklyn JA, Gough SC. Association of Fc receptor-like 5 (FCRL5) with Graves’ disease is secondary to the effect of FCRL3. Clin Endocrinol (2010) 73(5):654–60. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03843.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ban Y, Tozaki T, Tobe T, Ban Y, Jacobson EM, Concepcion ES, et al. The regulatory T cell gene FOXP3 and genetic susceptibility to thyroid autoimmunity: an association analysis in Caucasian and Japanese cohorts. J Autoimmun (2007) 28(4):201–7. 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graham RR, Kozyrev SV, Baechler EC, Reddy MV, Plenge RM, Bauer JW, et al. A common haplotype of interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) regulates splicing and expression and is associated with increased risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet (2006) 38(5):550–5. 10.1038/ng1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao W, Liu Z, Lin J, Xiong C, Li J, Wu K, et al. Association of TLR4 and TLR5 gene polymorphisms with Graves’ disease in Chinese Cantonese population. Hum Immunol (2014) 75(7):609–13. 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menconi F, Monti MC, Greenberg DA, Oashi T, Osman R, Davies TF, et al. Molecular amino acid signatures in the MHC class II peptide-binding pocket predispose to autoimmune thyroiditis in humans and in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2008) 105(37):14034–9. 10.1073/pnas.0806584105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clarke GM, Anderson CA, Pettersson FH, Cardon LR, Morris AP, Zondervan KT. Basic statistical analysis in genetic case-control studies. Nat Protoc (2011) 6(2):121–33. 10.1038/nprot.2010.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo T, Huo Y, Zhu W, Xu F, Liu C, Liu N, et al. Genetic association between IL-17F gene polymorphisms and the pathogenesis of Graves’ disease in the Han Chinese population. Gene (2013) 512(2):300–4. 10.1016/j.gene.2012.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brix TH, Petersen HC, Iachine I, Hegedus L. Preliminary evidence of genetic anticipation in Graves’ disease. Thyroid (2003) 13(5):447–51. 10.1089/105072503322021106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prabhakar BS, Bahn RS, Smith TJ. Current perspective on the pathogenesis of Graves’ disease and ophthalmopathy. Endocr Rev (2003) 24(6):802–35. 10.1210/er.2002-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stefan M, Wei C, Lombardi A, Li CW, Concepcion ES, Inabnet WB, III, et al. Genetic-epigenetic dysregulation of thymic TSH receptor gene expression triggers thyroid autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111(34):12562–7. 10.1073/pnas.1408821111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lombardi A, Inabnet WB, III, Owen R, Farenholtz KE, Tomer Y. Endoplasmic reticulum stress as a novel mechanism in amiodarone-induced destructive thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2015) 100(1):E1–10. 10.1210/jc.2014-2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petrone A, Giorgi G, Galgani A, Alemanno I, Corsello SM, Signore A, et al. CT60 single nucleotide polymorphisms of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 gene region is associated with Graves’ disease in an Italian population. Thyroid (2005) 15(3):232–8. 10.1089/thy.2005.15.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marron MP, Raffel LJ, Garchon HJ, Jacob CO, Serrano-Rios M, Martinez Larrad MT, et al. Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) is associated with CTLA4 polymorphisms in multiple ethnic groups. Hum Mol Genet (1997) 6(8):1275–82. 10.1093/hmg/6.8.1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawano H, Katayama Y, Minagawa K, Shimoyama M, Henkemeyer M, Matsui T. A novel feedback mechanism by ephrin-B1/B2 in T-cell activation involves a concentration-dependent switch from costimulation to inhibition. Eur J Immunol (2012) 42(6):1562–72. 10.1002/eji.201142175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo H, Charpentier T, Wang X, Qi S, Han B, Wu T, et al. Efnb1 and Efnb2 proteins regulate thymocyte development, peripheral T cell differentiation, and antiviral immune responses and are essential for interleukin-6 (IL-6) signaling. J Biol Chem (2011) 286(48):41135–52. 10.1074/jbc.M111.302596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miao Y, Yang J, Xu Z, Jing L, Zhao S, Li X. RNA sequencing identifies upregulated kyphoscoliosis peptidase and phosphatidic acid signaling pathways in muscle hypertrophy generated by transgenic expression of myostatin propeptide. Int J Mol Sci (2015) 16(4):7976–94. 10.3390/ijms16047976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Papassotiropoulos A, Stephan DA, Huentelman MJ, Hoerndli FJ, Craig DW, Pearson JV, et al. Common Kibra alleles are associated with human memory performance. Science (2006) 314(5798):475–8. 10.1126/science.1129837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniele S, Trincavelli ML, Fumagalli M, Zappelli E, Lecca D, Bonfanti E, et al. Does GRK-beta arrestin machinery work as a “switch on” for GPR17-mediated activation of intracellular signaling pathways? Cell Signal (2014) 26(6):1310–25. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Su L, Hu A, Luo Y, Zhou W, Zhang P, Feng Y. HMGN2, a new anti-tumor effector molecule of CD8(+) T cells. Mol Cancer (2014) 13:178. 10.1186/1476-4598-13-178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davison LJ, Wallace C, Cooper JD, Cope NF, Wilson NK, Smyth DJ, et al. Long-range DNA looping and gene expression analyses identify DEXI as an autoimmune disease candidate gene. Hum Mol Genet (2012) 21(2):322–33. 10.1093/hmg/ddr468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kilpinen H, Waszak SM, Gschwind AR, Raghav SK, Witwicki RM, Orioli A, et al. Coordinated effects of sequence variation on DNA binding, chromatin structure, and transcription. Science (2013) 342(6159):744–7. 10.1126/science.1242463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huber AK, Jacobson EM, Jazdzewski K, Concepcion ES, Tomer Y. Interleukin (IL)-23 receptor is a major susceptibility gene for Graves’ ophthalmopathy: the IL-23/T-helper 17 axis extends to thyroid autoimmunity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2008) 93(3):1077–81. 10.1210/jc.2007-2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charreire J. Immune mechanisms in autoimmune thyroiditis. Adv Immunol (1989) 46:263–334. 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60656-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nielsen CH, Moeller AC, Hegedus L, Bendtzen K, Leslie RG. Self-reactive CD4+ T cells and B cells in the blood in health and autoimmune disease: increased frequency of thyroglobulin-reactive cells in Graves’ disease. J Clin Immunol (2006) 26(2):126–37. 10.1007/s10875-006-9000-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shanmuganathan T, Girgis C, Lahooti H, Champion B, Wall JR. Does autoimmunity against thyroglobulin play a role in the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy: a review. Clin Ophthalmol (2015) 9:2271–6. 10.2147/OPTH.S88444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marino M, Chiovato L, Lisi S, Altea MA, Marcocci C, Pinchera A. Role of thyroglobulin in the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy: the hypothesis of Kriss revisited. J Endocrinol Invest (2004) 27(3):230–6. 10.1007/BF03345271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ban Y, Taniyama M, Ban Y. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism is associated with Graves’ disease in the Japanese population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2000) 85(12):4639–43. 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feng M, Li H, Chen SF, Li WF, Zhang FB. Polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor gene and risk of autoimmune thyroid diseases: a meta-analysis. Endocrine (2013) 43(2):318–26. 10.1007/s12020-012-9812-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurylowicz A, Ramos-Lopez E, Bednarczuk T, Badenhoop K. Vitamin D-binding protein (DBP) gene polymorphism is associated with Graves’ disease and the vitamin D status in a Polish population study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes (2006) 114(6):329–35. 10.1055/s-2006-924256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.D’Aurizio F, Villalta D, Metus P, Doretto P, Tozzoli R. Is vitamin D a player or not in the pathophysiology of autoimmune thyroid diseases? Autoimmun Rev (2015) 14(5):363–9. 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rotondi M, Chiovato L. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with Graves’ disease: probably something more than a casual association. Endocrine (2013) 43(1):3–5. 10.1007/s12020-012-9776-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vaidya B, Imrie H, Geatch DR, Perros P, Ball SG, Baylis PH, et al. Association analysis of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) and autoimmune regulator-1 (AIRE-1) genes in sporadic autoimmune Addison’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2000) 85(2):688–91. 10.1210/jcem.85.2.6369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chistiakov DA, Turakulov RI. CTLA-4 and its role in autoimmune thyroid disease. J Mol Endocrinol (2003) 31(1):21–36. 10.1677/jme.0.0310021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu J, Zhang HX. CTLA-4 gene and the susceptibility of multiple sclerosis: an updated meta-analysis study including 12,916 cases and 15,455 controls. J Neurogenet (2014) 28(1–2):153–63. 10.3109/01677063.2014.880703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yanagawa T, Hidaka Y, Guimaraes V, Soliman M, DeGroot LJ. CTLA-4 gene polymorphism associated with Graves’ disease in a Caucasian population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (1995) 80(1):41–5. 10.1210/jcem.80.1.7829637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tomer Y, Concepcion E, Greenberg DA. A C/T single-nucleotide polymorphism in the region of the CD40 gene is associated with Graves’ disease. Thyroid (2002) 12(12):1129–35. 10.1089/105072502321085234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]