Abstract

The bacterial genus Endozoicomonas was commonly detected in healthy corals in many coral-associated bacteria studies in the past decade. Although, it is likely to be a core member of coral microbiota, little is known about its ecological roles. To decipher potential interactions between bacteria and their coral hosts, we sequenced and investigated the first culturable endozoicomonal bacterium from coral, the E. montiporae CL-33T. Its genome had potential sign of ongoing genome erosion and gene exchange with its host. Testosterone degradation and type III secretion system are commonly present in Endozoicomonas and may have roles to recognize and deliver effectors to their hosts. Moreover, genes of eukaryotic ephrin ligand B2 are present in its genome; presumably, this bacterium could move into coral cells via endocytosis after binding to coral's Eph receptors. In addition, 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine triphosphatase and isocitrate lyase are possible type III secretion effectors that might help coral to prevent mitochondrial dysfunction and promote gluconeogenesis, especially under stress conditions. Based on all these findings, we inferred that E. montiporae was a facultative endosymbiont that can recognize, translocate, communicate and modulate its coral host.

Keywords: Endozoicomonas, host–bacteria interaction, comparative genomics, endosymbiosis, coral holobiont

Introduction

The bacterial genus Endozoicomonas was first proposed by Kurahashi and Yokota (2007). All culturable species of this genus were isolated from marine invertebrates, including sea slug (Kurahashi and Yokota, 2007), encrusting coral (Yang et al., 2010), sponge (Nishijima et al., 2013), octocorals (Pike et al., 2013), and comb pen shell (Hyun et al., 2014). In culture-independent bacterial community studies, Endozoicomonas were frequently detected in various marine invertebrates and have been considered an important affiliate of the host holobiont, due to their positive association with healthy individuals, particularly in corals. For example, Vezzulli et al. (2013) compared bacterial communities on Mediterranean gorgonians (Paramuricea clavata) and reported that Endozoicomonas were a predominant group on healthy individuals, but declined greatly when their host was diseased. Similarly, Meyer et al. (2014) also noted that the Endozoicomonas was a predominant group in mucus of healthy corals, Porites astreoides, but was significantly less abundant when hosts were injured or diseased. Moreover, relative abundance of Endozoicomonas was altered following increased pCO2 in surrounding seawater or elevated seawater temperature (Morrow et al., 2015; Tout et al., 2015). Furthermore, the predominance of Endozoicomonas might also link to their host's prevalence in nature. In a survey of the distribution of the fungid coral Ctenactis echinata, Roder et al. (2015) reported that when C. echinata was most abundant, the microbiome was highly structured and dominated by Endozoicomonas. In contrast, when C. echinata was less abundant, bacterial communities became diverse and proportion of Endozoicomonas also decreased. A similar phenomenon was also reported by Roterman et al. (2015) regarding the oyster Spondylus in the Mediterranean Sea. In addition, two reports suggested that Endozoicomonas or Endozoicomonas-like bacteria might have a role in sulfur cycling (Raina et al., 2009) and production of antimicrobial compounds (Rua et al., 2014). Taken together, although numerous studies have highlighted the potential importance of Endozoicomonas for corals or reef invertebrates, the genetics, physiology, and ecology of these bacteria are mostly unknown.

Endozoicomonas montiporae CL-33T was the first culturable coral-associated endozoicomonal bacteria, which was isolated from the encrusting pore coral Montipora aequituberculata at the southern coast offshore of Taiwan (Yang et al., 2010). That this species is culturable facilitates in-depth studies, particularly on genetics and physiology. Hence, in this study, we presented a high quality, nearly complete genome sequence of E. montiporae, and deciphered possible ecological functions of this bacterium, based on comparative genomic approaches and physiological tests. Our discoveries provided evidence-based insights regarding how E. montiporae interacted with its host from outside to inside of the coral cell. In addition, based on unique genomic features and newly discovered potential functions, we inferred that E. montiporae can be a facultative endosymbiont with the capability of helping its host to overcome environmental stresses.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, medium, and culture conditions

The strain of E. montiporae (CL-33T) was obtained from a previous study (Yang et al., 2010). Type strains of Endozoicomonas elysicola (DSM 22380T), Endozoicomonas numazuensis (DSM 25634T), and Vibrio corallilyticus (DSM 19607T) were purchased from Leibniz-Institut DSMZ—Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany). Routine cultivation was done on MMB medium (per liter: 19.45 g of NaCl, 18.79 g of MgCl2·6H2O, 3.24 g of Na2SO4, 0.55 g of KCl, 0.16 g of NaHCO3, 0.12 g of CaCl2, 2 mg of KNO3, 8 mg of NaHPO4, 5 g of peptone, 1 g of yeast extract, 1 ml of trace element (Guillard and Ryther, 1962), 5.95 g of HEPES, pH 7.2), whereas for high-density cultivation of E. montiporae, 0.1% (w/v) of glucose/maltose was added to MMB. For sole carbon usage test, the MM medium (the same ingredients as MMB except the NaHPO4, peptone, and yeast extract were replaced by 100 μg of cyanocobalamin and 1 ml of 1M K-phosphate buffer) was used and test carbon sources, including glucose and testosterone, were added at 1% (w/v) and 500 μM, respectively. All bacterial strains were aerobically cultured at 25°C with 200 rpm agitation.

Genomic DNA extraction, sequencing, and genome assemble

Genomic DNA of E. montiporae was extracted by the CTAB method, as described (Wilson, 2001). A physical map of E. montiporae genome was constructed from fresh cultures using an optical mapping technology, the ARGUS System (OpGen, Gaithersburg, ML, USA), at Yourgene Bioscience (New Taipei City, Taiwan). Purified genomic DNA was sequenced on three platforms: Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), Roche 454 GS Junior (Roche 454 Life Sciences, Branford, CT, USA) and Pacific Biosciences RS II (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA). Three DNA libraries were prepared for Illumina sequencing: paired-end library (fragment size ~500 bp), PCR-free library (fragment size ~350 bp), and mate-paired library (fragment size ~4 Kbp). For pyrosequencing (454) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) sequencing, one flow cell and one SMRT cell were used for sequencing, respectively. The total read length from high-throughput sequencing was ~10,718 Mbp. Furthermore, CLC Workstation 6 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark) was used to trim low-quality bases off Illumina and 454 raw reads. Illumina and PacBio reads were de novo assembled using ALLPATHS-LG (Butler et al., 2008) and SMRT-Analysis 2.2 (Pacific Biosciences, CA, USA), respectively. Scaffolds from Illumina and PacBio assemblies were analyzed in MapSolver™ (OpGen) to construct chromosomal scaffold by aligning the AflII cutter (CTTAAG) identified in contig sequences to the optical map. Both GMcloser (Kosugi et al., 2015) and GapFiller (Nadalin et al., 2012) were used in gap filling with PacBio and Illumina reads, respectively. When using GMcloser, 454 reads were used to correct PacBio reads with the PBcR pipeline (Berlin et al., 2015) of Celera Assembler 8.2 (Myers et al., 2000) before gap filling. The sequences of rRNA operons were confirmed with molecular cloning method (see below).

Genome annotation and bioinformatic analysis

The assembled genome was first subjected into non-coding gene predictions with tRNAscan-SE 1.3.1 (Lowe and Eddy, 1997), CRISPRFinder (Grissa et al., 2007), and using an HMM search with Rfam database 12 (Nawrocki et al., 2015). After masking predicted non-coding regions, coding genes were predicted with Prodigal-2.6 (Hyatt et al., 2010). Functional assignment for coding genes was accomplished with CDD (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2011), Pfam release 27 (Finn et al., 2014), COG 2014 update (Galperin et al., 2015), and NCBI PSI-BLAST against the Reference Sequence (RefSeq) database with the e-value threshold of 10−6. Metabolic pathways were analyzed with KEGG (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000) and MetaCyc (Karp et al., 2000). Gene annotations of the genome were manually revised and corrected using Artemis (Carver et al., 2011).

Prophage prediction was done with PHAST (Zhou et al., 2011). Repeat sequences were detected with UGENE (Okonechnikov et al., 2012), with a minimum length threshold of 500 bp and minimum identity of 98%. Regions containing rRNA genes (16S and 23S) were excluded from analyses. Repeat sequences were further identified using IS Finder database (https://www-is.biotoul.fr) with the e-value threshold of 10−6. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic subcellular location predictions were performed using Phobius (Käll et al., 2007) and BacelLo (set for prediction in animals; Pierleoni et al., 2006), respectively. The bacterial secretome was predicted using EffectiveT3 (set “gram-” for SignalIP, “type III effector prediction with animal set” for classification module and “selective” for cut-off; Arnold et al., 2009) and SSPred (set to use a Hybrid-II approach; Pundhir and Kumar, 2011). Coiled-coil prediction and homology modeling were performed using COILS (Lupas et al., 1991) and SWISS-MODEL (Biasini et al., 2014), respectively. GlycoEP (Chauhan et al., 2013) was used to predict N-glycosylation sites in eukaryotic proteins. A genome map was generated using Circos (Krzywinski et al., 2009). Visualization of protein models was done with UCSF Chimera v1.10.1 (Pettersen et al., 2004). Reference genomes/transcriptomes used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reference genomes/transcriptomes used for comparative analysis in this study.

| Organism name | Taxon (Phylum) | Lineage (Class/Order/Family) | References/Data source |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANIMAL | |||

| Acropora digitifera | Cnidaria | Anthozoa/Scleractinia/Acroporidae | Shinzato et al., 2011 |

| Acropora millepora | Cnidaria | Anthozoa/Scleractinia/Acroporidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Aiptasia pallida | Cnidaria | Anthozoa/Actiniaria/Actiniidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Anemonia viridis | Cnidaria | Anthozoa/Actiniaria/Actiniidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Montastrea faveolata | Cnidaria | Anthozoa/Scleractinia/Montastraeidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Nematostella vectensis | Cnidaria | Anthozoa/Actiniaria/Edwardsiidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Porites astreoides | Cnidaria | Anthozoa/Scleractinia/Poritidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Elysia chlorotica | Mollusca | Gastropoda/-/Plakobranchidae | Bhattacharya et al., 2013 |

| Amphimedon quennslandica | Porifera | Demospongiae/Haplosclerida/Niphatidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Leucosolenia complicata | Porifera | Calcarea/Leucosolenida/Leucosoleniidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Oscarella carmela | Porifera | Homoscleromorpha/Homosclerophorida/Plakinidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| Sycon ciliatum | Porifera | Calcarea/Leucosolenida/Sycettidae | Hemmrich and Bosch, 2008 |

| BACTERIA | |||

| Alcanivorax borkumensis SK2 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Alcanivoracaceae | Schneiker et al., 2006 |

| Alcanivorax dieselolei B5 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Alcanivoracaceae | Lai et al., 2012 |

| Alcanivorax hongdengensis A-11-3 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Alcanivoracaceae | Lai and Shao, 2012 |

| Bermanella marisrubri RED65 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Oceanospirillaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Chromohalobacter israelensis ATCC 43985 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Halomonadaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Chromohalobacter salexigens DSM 3043 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Halomonadaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Endozoicomonas elysicola DSM 22380 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Hahellaceae | Neave et al., 2014 |

| Endozoicomonas numazuensis DSM 25634 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Hahellaceae | Neave et al., 2014 |

| Hahella chejuensis KCTC 2396 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Hahellaceae | Jeong et al., 2005 |

| Hahella ganghwensis DSM 17046 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Hahellaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Halomonas daqiaogenesis CGMCC 1.9150 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Halomonadaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Halomonas elongata DSM 2581 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Halomonadaceae | Schwibbert et al., 2011 |

| Halomonas halocynthiae DSM 14573 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Halomonadaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Kangiella aquimarina DSM 16071 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Alcanivoracaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Kangiella koreensis DSM 16069 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Alcanivoracaceae | Han et al., 2009 |

| Marinomonas mediterranea MMB 1 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Oceanospirillaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Marinomonas posidonica IVIA-Po-181 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Oceanospirillaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Thalassolituus oleivorans MIL-1 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Oceanospirillales/Oceanospirillaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Vibrio coralliilyticus ATCC BAA-450 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Vibrionales/Vibrionaceae | Kimes et al., 2012 |

| Vibrio harveyi ATCC BAA-1116 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Vibrionales/Vibrionaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

| Vibrio shilonii AK1 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria/Vibrionales/Vibrionaceae | Integrated microbial genomes |

Amplification, cloning, and sequencing rrn operons

Five operon-specific forward primers (rrnA_f, rrnB_f, rrnC_f, rrnD_f, and rrnE_f) and one universal reverse primer (rrnUniv_r; Supplementary Table S1) were designed from flanking regions of rrnA-rrnE. Target DNA fragments were amplified by using Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and PCR reactants were prepared according to manufacturer's instruction. The amplification was done with 35 cycles of: 98°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, 72°C for 190 s. Amplified products were separated with agarose gel electrophoresis and DNA bands with expected size (~5.5 Kbp) were eluted by QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Purified DNAs were subjected into an A-tailing reaction with Ex Taq DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) and TA-cloning with pGEM-T vector system (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) according to manufacturer's instruction. Cloned DNAs were transformed into One Shot® TOP10 Chemically Competent E. coli and transformants were screened with β-galactosidase α-complementation. Purification of plasmid DNAs and Sanger sequencing the insert DNAs were carried out at Genomics Inc. (New Taipei City, Taiwan). For complete sequencing the cloned rRNA operons, 16 universal walking primers were designed (Supplementary Table S1).

Steroids degradation and detection

Test strains were aerobically cultured in MMB supplied with 0.1% (w/v) of maltose and 500 μM of testosterone. On each day, 1 ml of culture sample was taken, vigorously mixed with 0.8 ml of ethyl acetate and centrifuged (10,000 × g, 4°C, 10 min). After centrifugation, 0.6 ml of the upper-most layer was withdrawn and vacuum-dried. For detection of testosterone-derived compounds, dried samples were dissolved in 40 μl of ethyl acetate and 5 μl applied on TLC Silica gel 60 F254 plates (MERCK, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) and developed in dichloromethane:ethyl acetate:ethanol (7:2:0.5, v/v; Chiang et al., 2010). The separated metabolites were visualized by spraying on plates with 40% sulfuric acid solution, followed by heating at 150°C.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The genome sequence of E. montiporae and its annotation were deposited at GenBank under BioProject Number PRJNA66389 (Registration date: 28-Apr-2011).

Results and discussion

General genomic features

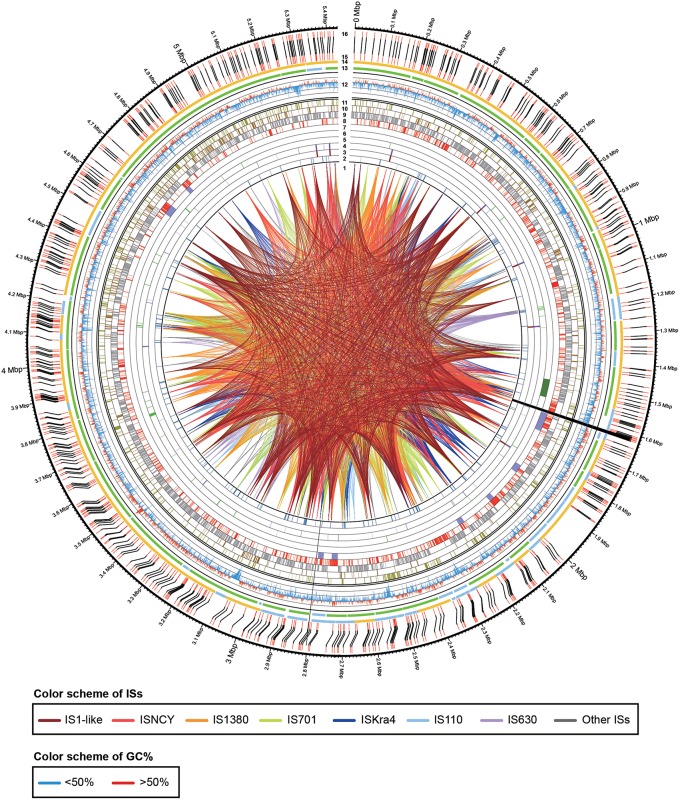

The extracted genomic DNA of E. montiporae was sequenced though five libraries in three next-generation platforms and reads were assembled into one circular chromosome ~5.43 Mbp and ~1900-fold in coverage depth. Two gaps (~9.8 and 1.0 Kbp) remained (genome completeness was approximately 99.80%). At the beginning, lengths of assembled contigs from Illumina/454 reads were highly fragmented and in silico AflII patterns of contigs were not properly matched to the physical map generated by optical mapping technology. We also noticed that a previously released E. montiporae genome (Neave et al., 2014) had the same limitation, which was attributed to sequence assemblies being greatly affected by numerous repeat sequences (which are longer than sequencing reads). Therefore, PacBio long-read sequencing technology was used. After incorporating long-reads, the final assembly had good agreement in AflII cutting pattern (indicates the genome was accurately assembled; Figure 1). Detailed genome statistics are listed (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Physical and genetic maps of the genome of E. montiporae. The track numbers represent: (1), IS linkages; (2), pseudogenes; (3), rRNA operons; (4), tRNAs; (5), eukaryotic domain proteins; (6), testosterone degrading gene cluster; (7), prophage regions; (8), unique genes in E. montiporae; (9), conserved genes in three Endozoicomonas; (10), genes shared with E. numazuensis; (11), genes shared with E. elysicola; (12), GC profile (red, > 50%; blue, < 50%); (13), ALLPATH-LG assembled scaffolds (green, orientated by MpSolver; light blue, orientated in gap filling process); (14), SMRTAnalysis assembled scaffolds (yellow, orientated by MpSolver; light blue, orientated in gap filling process); (15), AflII pattern from assembled sequences; (16) physical map (AflII cuts) generated with optical mapping technology. The black lines that connect track 15 and 16 indicated the alignment of AflII cuts from assemble genome sequence and physical map. The two assembly gaps are indicated by black near position 1.6 and 2.8 Mbp.

Table 2.

Generic features of the E. montiporae draft genome sequence.

| Parameter | E. montiporae |

|---|---|

| Genome size (estimated from optical mapping) | 5,432,010 bp |

| Total size of genome assembly | 5,430,252 bp |

| GC content | 48.37% |

| Number of coding sequences | 4572 |

| Number of rRNA operons | 7 |

| 5S rRNA gene | 8 |

| 16S rRNA gene | 7 |

| 23S rRNA gene | 7 |

| Number of tRNAs | 109 |

| Number of non-coding genes | 55 |

| Number of pseudogenes/frame-shifted genes | 198 |

| Number of CPISPR arrays | 5 |

The genome contained seven rRNA operons. The 16S-23S rRNA gene copy number in E. montiporae differed from that in other reported endozoicomonal genomes (16S/23S: E. elysicola, 6/6; E. numazuensis, 5/2; E. montiporae, 4/4; Neave et al., 2014). In contrast, the copy number of 5S rRNA gene was 8 (E. elysicola and E. montiporae, 8; E. numazuensis, 3; Neave et al., 2014). The rRNA operon rrnD was the only operon that contained two copies of 5S rRNA genes (Supplementary Information). In the orthology analysis, E. montiporae shared ~59.49 and ~63.09% coding genes with E. elysiola and E. numazuensis genomes, respectively. In the metabolic pathway analysis, the three species had the potential to synthesize all proteinogenic amino acids and many cofactors, prosthetic group and electron carriers required for growth, except vitamin B12.

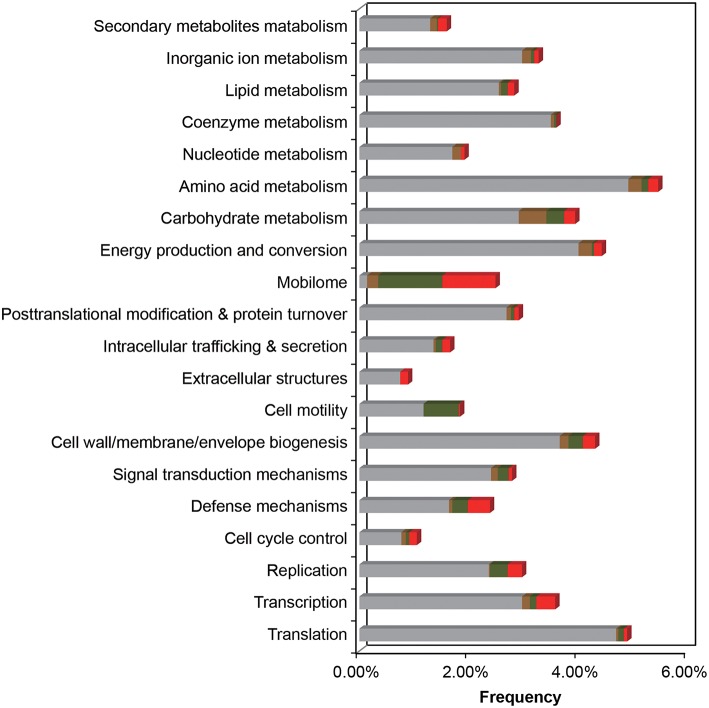

In the comparative analysis, there were 1179 coding genes that could only be detected in E. montiporae (Figure 1). Based on the COG functional profile, E. montiporae had a higher proportion of genes (2.5% of all COGs) related to the mobilome (Figure 2). Many genes within the mobilome were similar to phage structural proteins (i.e., phage capsid or tail proteins), indicating frequent interactions between E. montiporae and its infectious agents, bacteriophages. Based on prophage prediction, there were eight prophages in the genome (ranging from 15.5 to 75 Kbp; Table 3). Four of those prophages were predicted as intact lysogenic phages, similar to Vibrio phage vB VpaM MAR (region 1 in the genome), Vibrio phage VPUSM 8 (regions 2 and 3), and Escherichia phage vB_EcoM-ep3 (region 4). In contrast, no prophage was detected in the draft genome of E. elysicola and E. numazuensis.

Figure 2.

Functional COG profile of the E. montiporae genome. Genes shared in three Endozoicomonas, with E. numazuensis, with E. elysicola, or unique in E. montiporae are highlighted as gray, brown, green, and red with respectively. Corresponding locations are shown in Figure 1 (track 8–11).

Table 3.

Prophage regions identified in the genome of E. montiporae.

| Region | Position | Length (Kbp) | Completeness | PHAST score | ORF number | Unique ORFs | Possible phage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1624494–1699528 | 75 | Intact | 150 | 99 | 69 | Vibrio phage vB VpaM MAR (NC_109722) |

| 2 | 2025905–2046887 | 20.9 | Intact | 140 | 25 | 25 | Vibrio phage VPUSM 8 (NC_022747) |

| 3 | 2717260–2741388 | 24.1 | Intact | 140 | 32 | 31 | Vibrio phage VPUSM 8 (NC_022747) |

| 4 | 4621590–4662332 | 40.7 | Intact | 150 | 67 | 62 | Escherichia phage vB_EcoM-ep3 (NC_025430) |

| 5 | 1858945–1891753 | 32.8 | Incomplete | 60 | 31 | 13 | Staphylococcus prophage phiPV83 (NC_002486) |

| 6 | 2179474–2203283 | 23.8 | Incomplete | 40 | 21 | 10 | Stenotrophomonas phage S1 (NC_011589) |

| 7 | 2774561–2790090 | 15.5 | Incomplete | 50 | 28 | 24 | Pseudoalteromonas phage PM2 (NC_000867) |

| 8 | 4748489–4767285 | 18.7 | Incomplete | 30 | 27 | 21 | Rhizobium phage RR1-B (NC_021557) |

The E. montiporae genome contained at least 452 mobile elements, which include 46 IS1-like IS elements (most active), 36 of Group II introns and 370 of integrase/transposase coding genes from various IS families. The estimated repeat coverage in E. montiporae was ~9.07%, greatly higher than E. elysicola and E. numazuensis, which were only ~0.11 and ~4.05%, respectively (Figure 1, also see Supplementary Figure S1). Those mobile elements were likely still active in E. montiporae, because 56 genes were inactivated due to insertions (Supplementary Table S2).

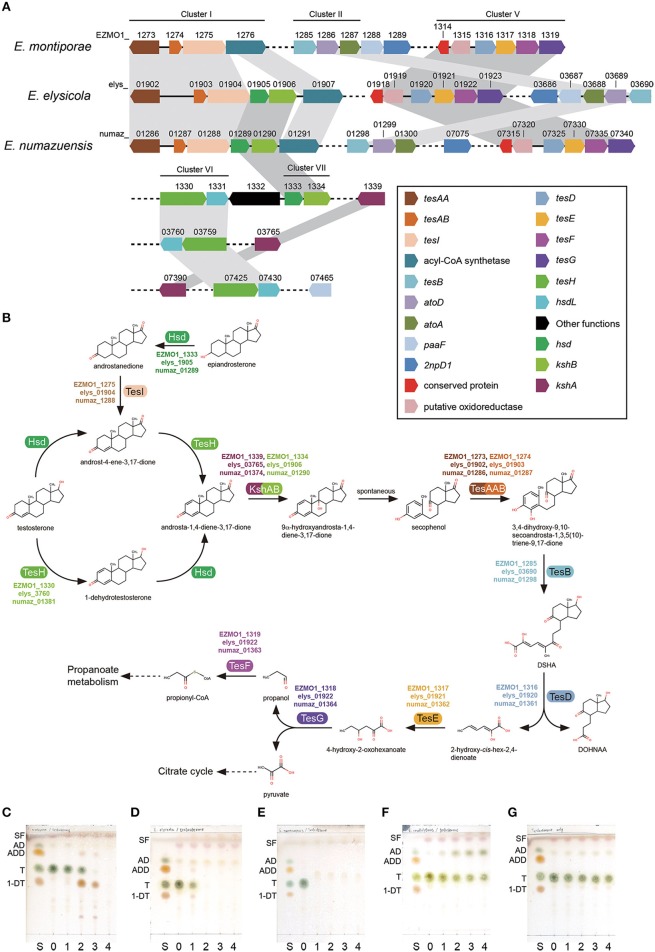

Endozoicomonas montiporae is a testosterone degrader

The three endozoicomonal species in the present study shared high similarities in metabolic capacities. It was noteworthy that they all had genes for degrading testosterone (male sex hormone), although that was rarely reported in oceanospirial genomes. Key genes required for degrading testosterone were detected within five of seven conserved gene clusters (I, II, V, VI, and VII) in the endozoicomonal genomes (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table S3). From a reconstructed pathway, testosterone could be degraded into propionyl-CoA and pyruvate through the 9,10-seco pathway (Coulter and Talalay, 1968). Furthermore, the first two metabolites could be further utilized (via propionate metabolism and TCA cycle) in the Endozoicomonas species (Figure 3B). Clusters III and IV were mainly composed of genes related to fatty acid β-oxidation (Supplementary Table S3). Interestingly, those genes formed conserved synteny with known aerobic testosterone-degrading bacteria (Horinouchi et al., 2012), indicating those genes were probably acquired via horizontal gene transfer. In our degradation tests, all three Endozoicomonas were able to completely degrade testosterone (Figures 3C–E, with Endozoicomonas; Figure 3G, medium only control). In contrast, there were no genes related to testosterone degradation identified in Vibrio species and the coral pathogen V. corallilyticus had a negative reaction regarding testosterone degradation (Figure 3F). When minimal medium was used to determine whether testosterone could serve as sole carbon source for growth, only E. elysicola and E. numazuensis, but not E. montiporae, grew (albeit with a very low biomass; i.e., OD600 ~0.1). Low testosterone concentrations can be detected in coral reef seawater, with highest concentrations in coral tissues (42.7 ng/g tissue in conjugated form; Twan et al., 2006). However, the concentration was still ~5,300-fold lower than our tests, suggesting that testosterone might not be a nutrient but more like an “animal cue” for Endozoicomonas.

Figure 3.

Testosterone degradation in Endozoicomonas. The gene order of key genes required for degradation (A) and their corresponding reactions (B) presented in Endozoicomonas species. Degrading capabilities of test bacteria were confirmed by supplying 500 μM of testosterone in culture medium and sampled daily in the previous culture. Test bacteria are: E. montiporae (C), E. elysicola (D), E. numazuensis (E), V. corallilyticus (F), and a blank control without inoculum (G). Abbreviations used in TLC analysis are: 1-DT, 1-dehydrotestosterone; AD, androst-4-ene-3,17-dione; ADD, androsta-1,4-diene-3,17-dione; S, standard mixture; SF, solvent front; T, testosterone. Numbers stand for the day of culture.

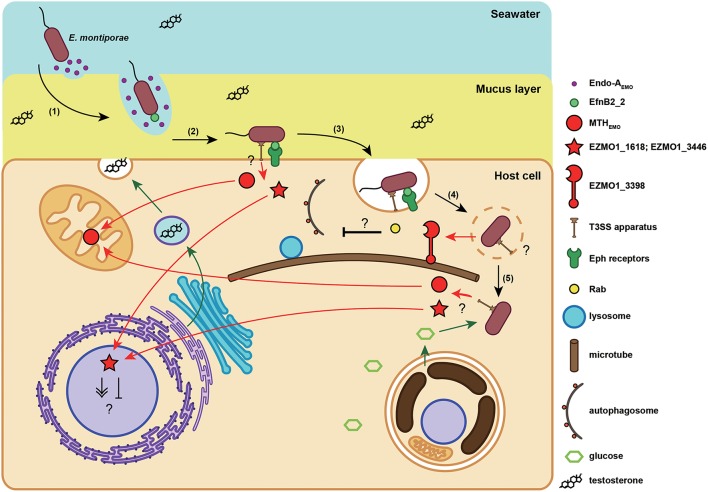

Endozoicomonas montiporae possesses a N-deglycosylation enzyme that might help it to penetrate host's mucus layer

EZMO1_4380 (endo-AEmo) was a unique gene in E. montiporae. Its translated product was similar to endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase A (PDB number: 2VTF) from Arthrobacter protophormiae (Supplementary Figure S2). Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidases (ENGases) have been reported in a wide variety of organisms, with roles in hydrolyzing glycosidic bond present in N-linked sugar chains in glycoproteins (Yin et al., 2009). In contrast to those cytoplasmic ENGases in plants and animals, bacterial and fungal ENGases are secreted enzymes (Suzuki et al., 2002). The Endo-AEmo contained a signal peptide sequence at its N-terminus (1–25 residues), a hallmark feature of a secreted enzyme. The predicted function of this protein might be related to digest glycoproteins, which were commonly present in the natural habitats of E. montiporae, e.g., coral mucus. Glycoprotein mucins are the major structural component of coral mucus. However, only the O-linkage was experimentally detected in coral mucins (Meikle et al., 1987). In genomic surveys, the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis has an N-glycosylated mucin coding gene (XP_001636262; Lang et al., 2007). In addition, in the draft genome of the coral Acropora digitifera, open reading frames were detected in two regions located inside the scaffold 125 and 132 that resembled the mucin protein of N. vectensis and contained putative N-glycosylation sites. Therefore, we inferred that coral mucins could be N-glycosylated and physical characteristics might be affected due to deglycosylation by Endo-AEmo. Blocking N-glycosylation in rat Muc2 reduced gel formation and/or mucin viscoelasticity (Bell et al., 2003). Hence, relaxation of mucin by Endo-AEmo would facilitate E. montiporae to pass through coral mucus. Actually bacteria degrade mucin by two types of reactions, namely O-linkage hydrolysis and proteolysis (McGuckin et al., 2011). However, no similar homologs related to enzymes of the two reactions were detected in Endozoicomonas genomes, suggesting the bacteria might not be able to deeply decompose their host mucus. Perhaps the role of Endo-AEmo was not solely related to mucus dissociation, but it could help the bacterium to reach to specific host receptors on the cell membrane (Figure 4), similar to other bacteria (McGuckin et al., 2011).

Figure 4.

Proposed infection model of the E. montiporae. When E. montiporae attaches to the host mucus layer, secreted Endo-AEMO could reduce mucus viscosity, enabling the bacterium to penetrate through the mucus (1). Once the bacterium reached the host plasma membrane, the EfnB2_2 could bind with host Eph receptors (2), and initiate endocytosis (3). When E. montiporae enters into a host cell, it might use extracellular enzymes to disrupt the endosome and interfere with phagolysosome maturation by chelating Rabs with EZMO1_3398 (4). After escaping the endosome, E. montiporae could utilize nutrients in the host cytoplasm, particularly glucose produced by endosymbiotic zooxanthellae (5).

Host's ephrin receptors might be involved in endocytosis of E. montiporae

Two genes, EZMO1_1051 (efnB2_1) and EZMO1_3739 (efnB2_2), encoded proteins similar to eukaryotic proteins, but lacking orthologs in other bacteria. In that regard, EfnB2_1 and EfnB2_2 corresponded to NEMVEDRAFT_v1g212995 and NEMVEDRAFT_v1g236436 from N. vectensis, with 39 and 34% amino acid identities, respectively. Both EfnB2_1 and EfnB2_2 contained ephrin ectodomain (cd02675) and secretion signals at their N-terminus. Besides, EfnB2_2 encompassed transmembrane regions and was predicted as a membrane protein that could adhere on a cell surface, whereas EfnB2_1 was not. Tertiary structures of the two proteins, predicted by homology modeling, were very similar to each other, and they also resembled type B ephrin-B2 from mouse (1IKO; Supplementary Figure S3). However, it is noteworthy that the ephrin ligand protein was similar to the cupredoxin domain, a protein domain containing copper binding sites and usually responsible for electron-transfer reactions in bacteria (De Rienzo et al., 2004). Distinct from cupredox domain proteins, ephrin acts as a signal molecule in animals, with no metal-binding capability (Toth et al., 2001). For the two proteins, EfnB2_1 and EfnB2_2, all lacked copper binding residues by aligning with bacterial cupredoxins (azurins and auracyanins), indicating that the functions of EfnB2_1 and EfnB2_2 were more similar to eukaryotic ephrin ligand.

In vertebrates, ephrins are ligands for ephrin receptors (Ephs) and binding can activate intracellular signal pathways involved in a variety of cellular functions, including differentiation, migration, segmentation, and endocytosis (Kullander and Klein, 2002; Pitulescu and Adams, 2010). In cnidarian, ephrins, and Ephs in Hydra vulgaris belonged to type B (Tischer et al., 2013). Furthermore, ephrin ligands and receptors were strongly expressed on endoderm of tentacles and buds, suggesting ephrin-Eph signaling might have roles in cell adhesion and tissue boundary formation in H. vularis (Tischer et al., 2013). Ephrin-Eph signaling in corals has never been discussed; however, ephrin/Eph receptor genes were present in the genome of A. digitifera and the ephrin ligand gene was differentially expressed in A. palmata larvae (Polato et al., 2013), indicating that ephrin-Eph signaling could have roles in corals.

Although, the reason why E. montiporae has ephrin genes remains unknown, the rare occurrence of eukaryotic cell surface ligand coding genes might have a role in targeting host receptor and initiating internalization. In contrast, pathogenic bacteria can use azurin, a cupredoxin protein similar to ephrin in structure, to invade host cells. For example, bacterial azurin can solely enter the murine macrophage J774, as well as several types of cancer cells and trigger programed cell death of mammalian cell lines by interfering with Eph signal pathways (Yamada et al., 2005; Chaudhari et al., 2007). Furthermore, azurin in the human pathogen Neisseria gonorrhoeae is essential for survival inside host cells (Wu et al., 2005). Azurin othologous genes were only detected in three pathogenic Vibrio genomes, but not in the three Endozoicomonas. Accordingly, we speculated that the ephrin ligand in E. montiporae could serve as a “cloak” and facilitate this bacterium to enter host cells, but would not impair its host (Figure 4).

A giant secreted protein of E. montiporae might modulate host's intracellular vesicle trafficking

To survive inside a host cell, intracellular pathogens and symbionts have to evade the host defense system, which relies on intracellular vesicle trafficking (Davy et al., 2012; Ashida et al., 2015). In the present study, it was determined that E. montiporae contained at least one gene that may be essential for this purpose. In that regard, EZMO1_3398 is a giant extracellular protein-coding gene, which encodes 3872 amino acids and comprises the myosin tail (pfam01576) and Mycoplasma helix-rich (TIGR04523) domains at its N-terminus (Supplementary Figure S4A). Furthermore, EZMO1_3398 was predicted as a Sec-dependent secreted protein but not a membrane protein. The myosin tail domain contains α-helices that can form a coiled-coil structure for dimerization (Krendel and Mooseker, 2005). Regarding the Mycoplasma helix-rich domain, it is still functionally unclear, although it is common in Mycoplasma species.

Based on structure prediction, EZMO1_3398 could be a chimeric protein, encompassing bacterial and eukaryotic protein features. Potential functions could involve modulating host's intracellular trafficking processes, particularly during initial stages of infection (Figure 4). Three protein substructures were detected in the EZMO1_3398, including the tail of myosin (1I84), LidA (3TNF), and stalk with microtubule-binding domain from dynein 2 (4RH7), at its first half (Supplementary Figure S4A). The LidA-like structure was a core domain that connected the myosin tail-like and the dynein 2 stalk-like structures to its helix-1 and helix-7, respectively (Figures S4C–E). However, no myosin/dynein motor domains were identified, neither in sequence nor in structure similarities, in EZMO1_3398. The LidA protein of Legionella penumophila is a Rab supereffector protein that strongly binds to host's Rab proteins and might help L. penumophila to survive inside a host cell by preventing autophagosome maturation (Joshi and Swanson, 2011; Schoebel et al., 2011). Interfering with Rab proteins inside hosts seems to be a common strategy also used by endosymbionts to establish a symbiotic relationship. Even though a detailed mechanism is unclear, study of Symbiodinium-Aiptasia pulchella symbiosis suggests the symbiotic zooxanthellae could manipulate endosomal trafficking and prevent lysosome fusion (Davy et al., 2012). Rab proteins can perform several cellular functions when binding to various effector proteins. Regarding vesicle movement, Rabs can recruit myosins or dyneins to exert movement along microtubes. Binding with effectors and GTPase activating protein can activate the GTPase activity of Rab and hydrolysis of GTP can trigger movement (Hutagalung and Novick, 2011). Interestingly, EZMO1_3398 contained substructures similar to myosin and dynein and both are connected with the Rab-binding central domain. Therefore, the EZMO1_3398 might be able to attach host's microtubes via binding certain Rab proteins for some functional purposes, e.g., to prevent lysosome fusion (Figure 4).

Type III secretion effector proteins might help E. montiporae to infect coral host and mediate host's metabolism

A common feature of the Endozoicomonas species in this study is that they all had a host-dependent secretion system, the type III secretion system (T3SS), a well-known bacterial secretion system that is functionally involved in bacteria–host interactions, either symbiosis or pathogenesis (Preston, 2007). The presence of T3SS in the Endozoicomonas suggests they are capable of interacting with their hosts. To identify potential interactions between E. montiporae and its coral host, we analyzed predicted T3SS secretomes and the possible subcellular locations of those secreted proteins (i.e., effectors). There were 242 proteins predicted to be T3SS effectors, including many hypothetical proteins (Supplementary Table S4). Among those possible T3SS effectors, five proteins might be involved in survival inside hosts, regulating host's metabolism and/or increasing host's fitness.

EZMO1_0953 is a catalase gene of E. montiporae and its product was one of the T3SS effectors. Besides, catalase was a common T3SS-screted protein in other Endozoicomonas. Secretion of catalase by a host-dependent system indicated that the H2O2-scavenging enzyme might be crucial for Endozoicomonas to live within their hosts. For animal-associated bacteria, including pathogens, parasites, or symbionts, catalase activity is important for them to survive in their hosts (Bishai et al., 1994; Rocha et al., 1996; Visick and Ruby, 1998). Interestingly, instead of catalase, we identified another type of H2O2-removing enzyme, the thiol peroxidases (Tpx), that could be secreted via T3SS in pathogenic bacteria Vibrio. Tpx is a part of T3SS assembly in the human pathogen Yersinia species and also connects to effector delivery (Wang et al., 2011). In Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7, Tpx is required for biofilm formation on the human HT-29 cell line (Kim et al., 2006). The same gene was detected and predicted as a T3SS-secreted protein in our analysis. Collectively, we speculated that the T3SS-secreted antioxidant profile could be a distinguishable signature between pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria.

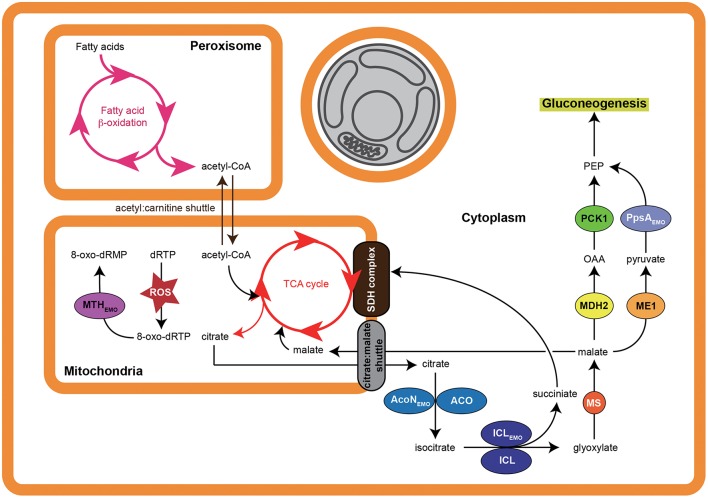

EZMO1_3421 encodes isocitrate lyase (ICLEmo), a key enzyme of the glyoxylate cycle, and was a predicted T3SS secreted protein in E. montiporae. The glyoxylate cycle is common in bacteria, fungi and plants, and can bypass carbon flow from fatty acid degradation to gluconeogenesis. Glyoxylate cycle enzymes are also present in nematodes and cnidarians (Kondrashov et al., 2006) and expression of ICL was detected in transcriptomes of A. millepora larvae and A. palmate (Meyer et al., 2009; Polato et al., 2013).

In addition to ICLEmo, there were two other T3SS effectors in E. montiporae that could concurrently work with the host enzymes for gluconeogenesis, namely EZMO1_2385 and EZMO1_2390 that encode the aconitate hydratase (AcoNEmo) and phosphoenolpyruvate synthase (PpsAEmo), respectively. In bacteria, AcoN and PpsA can redirect metabolites from the TCA cycle to gluconeogenesis. Up-regulation of fatty acid β-oxidation, glyoxylate cycle and gluconeogenesis have been proposed to enable corals to convert stored fatty acids to carbohydrates for surviving stress-induced starvation (Kenkel et al., 2013). Hence, coupling of T3SS secreted ICLEmo, AcoNEmo, and PpsAEmo from E. montiporae might increase metabolic efficiency of gluconeogenesis in the coral host. Furthermore, such metabolism integration might promote host survival under stressful conditions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Proposed pathway modulation model of E. montiporae. When the coral host is under stress, loss of symbiotic zooxanthellae (indicated by gray) makes host cell starts to use fatty acids and convert them into glucose. Active energy production and metabolite exchange could lead to accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mitochondria matrix, which can oxidize deoxyribose purine triphosphates (dRTP) into 8-oxo-dRTP and cause mutation. The T3SS secreted enzymes could hasten carbon flow from fatty acids to glucose and hydrolyze 8-oxo-dRTP inside mitochondria. The abbreviations of host enzymes are: ACO, aconitate hydratase; MS, malate synthase; ME1, NADP-dependent malic enzyme; MDH2, malate dehydrogenase (cytoplasmic).

Interestingly, we identified ICL orthologs that did not belong to T3SS effectors in E. elysicola and E. numazuensis. Notably, glyoxylate cycle enzymes were not detected in the representative genomes for their hosts (i.e., sea slug and sponge; Table 4). Besides, the predicted T3SS secretomes of Endozoicomonas were less common (Supplementary Table S4). Therefore, Endozoicomonas might have evolved unique strategies to interact with their own specific hosts.

Table 4.

Glyoxylate cycle enzymes (ICL and MS) in selected marine invertebrates.

| Type | Organism name | Data source | Number of BLAST hit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICL | MS | |||

| Coral | Acropora digitifera | Genome | 1 | 2 |

| Acropora millepora | ESTs | 1 | 2 | |

| Montastrea faveolata | ESTs | 3 | 1 | |

| Porites astreoides | ESTs | 2 | 2 | |

| Sea anemone | Aiptasia pallida | ESTs | 1 | 2 |

| Anemonia viridis | ESTs | 1 | 0 | |

| Nematostella vectensis | Genome | 1 | 2 | |

| Sea slug | Elysia chlorotica | SRA | 0 | 0 |

| Sponge | Amphimedon quennslandica | Genome | 0 | 0 |

| Leucosolenia complicata | Genome | 11 | 2 | |

| Oscarella carmela | Genome | 0 | 0 | |

| Sycon ciliatum | Genome | 2 | 0 | |

1. ICL and MS sequences from Saccharomyces cerevisiae were used as representitive sequences (queries).

2. When searching in EST database, tblastn was used and thresholds were set: e-value < 1e-15; bitscore > 100.

3. When searching in SRA database, tblastn was used first. Reads may affiliate with query sequences were recovered and subjected into blastn search against to nr/nt database. In blastn search, reads shared high identities and coverages to bacterial subjects will be excluded.

The EZMO1_3450 (mthEmo) encodes the 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine triphosphatase (MTH) and was another T3SS effector. The predicted subcellular location in host cell of MTHEmo was in the mitochondria. The MTH enzyme can hydrolyze damaged purine nucleoside triphosphates caused by attacks from reactive oxygen species and therefore can confer protection to the cell against various oxidative stresses. In animal models, MTH can prevent mitochondrial dysfunction, attenuate stress-induced cell death and enhance vitality (Ichikawa et al., 2008; De Luca et al., 2013). Even though the detailed mechanism is still unknown, bacterial endosymbiosis can prevent mitochondrial dysfunction in a mycorrhizal host and improve fitness of its fungal host during the pre-symbiotic rhizospheric phases (Salvioli et al., 2015). Exporting MTHEmo from E. montiporae to the host's mitochondria might promote mitochondrial functions. In addition, because mitochondria are also involved in fatty acid oxidation, MTHEmo could promote conversion of fatty acids to glucose in coral cells under bleaching stress (Figure 5). Accordingly, E. montiporae might be able to enhance host's fitness to environment changes by protecting mitochondria from the oxidative injury and/or altering carbon flows of host metabolism.

T3SS effectors might also involve in modulating host's signaling pathways

Two eukaryotic signal pathway proteins, serine/threonine protein kinase (STPK; EZMO1_1618 and EZMO1_3446), were predicted as T3SS effectors in E. montiporae. Both EZMO1_1618 and EZMO1_3446 were similar to STPK genes from the protozoa Trypanosoma congolense (TCIL3000_11_7730; identities: 33%) and the fungus Phytophthora nicotianae (L916_19948; identities: 34%), respectively. The two proteins were unlikely to be membrane-bound receptors, due to a lack of transmembrane regions in their amino acid sequences. Furthermore, predicted subcellular locations of EZMO1_1618 and EZMO1_3446 were all in the host nucleus (Figure 4). Bacterial types of STPKs can have roles during infection of their hosts (Whitmore and Lamont, 2012; Canova and Molle, 2014). For example, the human pathogen Yersinia species can secrete STPK protein (i.e., YopO) into host cells via T3SS and can interfere with the actin cytoskeleton of macrophage to prevent phagocytosis (Black et al., 2000; Juris et al., 2000; Grosdent et al., 2002). In contrast, the T3SS-secreted STPKs in E. montiporae were not similar to bacterial counterparts regarding protein orthology and predicted subcellular locations. Perhaps the two STPKs in E. montiporae were involved in altering certain gene expression in their host's nucleus.

Endozoicomonas montiporae could be a facultative coral endosymbiont

Based on niche specificity, special genomic characteristics, and growth features, we inferred that E. montiporae could be a facultative endosymbiotic bacterium in corals.

One of the indirect albeit rational evidences for niche specificity is that Endozoicomonas were mostly detected or isolated from tissues of marine invertebrates in reefs (Kurahashi and Yokota, 2007; Yang et al., 2010; Bourne et al., 2013; Nishijima et al., 2013; Pike et al., 2013; Hyun et al., 2014), implying their niches were likely associated with reef marine invertebrates. Moreover, the Endozoicomonas strains in this study all had genes of the host-dependent secretion system, carrying several putative animal genes and were able to degrade testosterone, strongly suggesting that the natural niche of those bacteria should be spatially close to or indeed within their animal hosts. We further deduced that the bacterial niches being intimate with host cells might be an important factor for gene transfer from hosts to bacteria.

Highly represented repeat sequences and pseudogenes in a bacterial genome could be a sign of genome erosion, a common feature in host-restricted symbionts or pathogens (McCutcheon and Moran, 2011). Occurrence frequencies of the IS and pseudogenes among the three endozoicomonal genomes could be grouped into various stages of genome erosion: E. elysicola, free-living; E. numazuensis, intermediate between free-living and host-restricted symbiont; and E. montiporae, a recently host-restricted symbiont/pathogen (Supplementary Figure S1) according to the category proposed by McCutcheon and Moran (2011). Such genomic features have been reported from an E. elysicola-like species, which may cause epitheliocystis in sharpsnout seabream larva (Katharios et al., 2015). Even though the genetic basis which can cause fish diseases remains unclear, increasing genome plasticity by accumulating a high proportion of insertion sequences or improving fitness to hosts by eliminating redundant genes through a pseudogenization process seemed to be a common strategy to survive inside host tissue. Furthermore, this was consistent with an evolutionary change toward tightly host-associated lifestyles that could occur in certain Endozoicomonas species.

Ecological roles of bacteria for mutualism or parasitism are commonly dynamic. Based on genomic analysis, we inferred that E. montiporae could be considered as a bacterium beneficial to corals. Not only does this bacterium have genes that could help its hosts, it was noteworthy that no known bacterial toxin homologs were present in its genome. However, potential parasitic roles of other Endozoicomonas species could not be excluded. For example, there are two reports that E. elysicola-like species could be associated with epitheliocystis in fish larvae (Mendoza et al., 2013; Katharios et al., 2015). However, these observations were different from previous surveys of marine invertebrates. Due to limited knowledge, it is unknown whether such different life styles of Endozoicomonas are due to genetic variations (e.g., presence or absence of virulence genes), physiological variations of their hosts, or both.

Some enzymes of E. montiporae could be secreted into host cytoplasm and promote glucose production in host cells. Glucose could be a critical factor in host cells and a feedback from the host cell, which can support growth of E. montiporae. In the present study, compared to other strains, E. montiporae did not achieve high-density growth in rich medium without glucose (Supplementary Figure S5). Therefore, supplying glucose could be a key to maintain a viable E. montiporae population inside corals.

To survive inside corals, it would be necessary for E. montiporae to communicate with its coral hosts as well as with endosymbiotic zooxanthellae, a key symbiotic partner inside coral cells. Glucose supply might be essential to maintain a symbiotic relationship between E. montiporae and coral. Therefore, it is also important to detect interactions between bacterial and algal endosymbionts. Therefore, we searched for potential proteins in the bacterium that could be involved in interactions, although none was detected. Unfortunately, our bioinformatics analyses lacked suitable models for prediction. In that regard, current prediction models of subcellular locations have not been established from corals or animals with algal endosymbionts. Therefore, for example, a protein could be translocated to specific organelles or compartments in which zooxanthellae reside, i.e., the symbiosome (Trench, 1979; Birkeland, 1997). It was noteworthy that eukaryotic domain protein coding genes present in E. montiporae, especially STPKs, were similar to proteins in invertebrates or fungi, but not plants. Therefore, we concluded that exchanges of genetic material between E. montiporae and zooxanthellae was unlikely. Although, our current results suggested the two endosymbionts might have no direct contact, we cannot assume that the E. montiporae does not communicate with algal symbionts, for example, by metabolites (Glick, 2012).

In conclusion, bacterial consortiums within corals are extremely complex and there has been a lack of detailed knowledge regarding interactions between bacteria and their coral host. Therefore, studying interactions between one bacterium and one coral species may provide more direct evidence and details. In this research, we focused on the Endozoicomonas, a group of bacteria present mainly on healthy coral, and how they may assist their hosts. We provided an abundance of genomic information, and discussed how Endozoicomonas, particularly E. montiporae could interact with their hosts. Our findings provided a valuable guide for future in-depth molecular or physiological studies for coral microbiology.

Author contributions

ST, WC, and JS conceived of the work. JD and JS conducted whole genome sequencing and were involved in genome assemble. JC contributed to comparative genome analysis, functional gene prediction, and other bioinformatics analysis. YC and JD designed the experiment of testosterone degradation and was carried out by JD. JD and ST contributed to writing the manuscript and JD elaborated the figures and tables. All authors critically reviewed, revised and ultimately approved this final version.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (Grant MOST 101-2628-B-001-001-MY3 and MOST 103-2811-B-001-066).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00251

References

- Arnold R., Brandmaier S., Kleine F., Tischler P., Heinz E., Behrens S., et al. (2009). Sequence-based prediction of type III secreted proteins. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000376. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashida H., Mimuro H., Sasakawa C. (2015). Shigella manipulates host immune responses by delivering effector proteins with specific roles. Front. Immunol. 6:219. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S. L., Xu G., Khatri I. A., Wang R., Rahman S., Forstner J. F. (2003). N-linked oligosaccharides play a role in disulphide-dependent dimerization of intestinal mucin Muc2. Biochem. J. 373, 893–900. 10.1042/BJ20030096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin K., Koren S., Chin C.-S., Drake J. P., Landolin J. M., Phillippy A. M. (2015). Assembling large genomes with single-molecule sequencing and locality-sensitive hashing. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 623–630. 10.1038/nbt.3238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya D., Pelletreau K. N., Price D. C., Sarver K. E., Rumpho M. E. (2013). Genome analysis of Elysia chlorotica egg DNA provides no evidence for horizontal gene transfer into the germ line of this kleptoplastic mollusc. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1843–1852. 10.1093/molbev/mst084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biasini M., Bienert S., Waterhouse A., Arnold K., Studer G., Schmidt T., et al. (2014). SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W252–W258. 10.1093/nar/gku340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkeland C. (ed.). (1997). Life and Death of Coral Reefs. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bishai W. R., Howard N. S., Winkelstein J. A., Smith H. O. (1994). Characterization and virulence analysis of catalase mutants of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 62, 4855–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black D. S., Marie-Cardine A., Schraven B., Bliska J. B. (2000). The Yersinia tyrosine phosphatase YopH targets a novel adhesion-regulated signalling complex in macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 2, 401–414. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne D. G., Dennis P. G., Uthicke S., Soo R. M., Tyson G. W., Webster N. (2013). Coral reef invertebrate microbiomes correlate with the presence of photosymbionts. ISME J. 7, 1452–1458. 10.1038/ismej.2012.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler J., MacCallum I., Kleber M., Shlyakhter I. A., Belmonte M. K., Lander E. S., et al. (2008). ALLPATHS: de novo assembly of whole-genome shotgun microreads. Genome Res. 18, 810–820. 10.1101/gr.7337908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canova M. J., Molle V. (2014). Bacterial Serine/Threonine Protein Kinases in Host-Pathogen Interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 9473–9479. 10.1074/jbc.R113.529917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver T., Harris S. R., Berriman M., Parkhill J., McQuillan J. A. (2011). Artemis: an integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics 28, 464–469. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari A., Mahfouz M., Fialho A. M., Yamada T., Granja A. T., Zhu Y., et al. (2007). Cupredoxin-cancer interrelationship: azurin binding with EphB2, interference in EphB2 tyrosine phosphorylation, and inhibition of cancer growth. Biochemistry 46, 1799–1810. 10.1021/bi061661x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan J. S., Rao A., Raghava G. P. S. (2013). In silico platform for prediction of N-, O- and C-glycosites in eukaryotic protein sequences. PLoS ONE 8:e67008. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang Y. R., Fang J. Y., Ismail W., Wang P. H. (2010). Initial steps in anoxic testosterone degradation by Steroidobacter denitrificans. Microbiology 156, 2253–2259. 10.1099/mic.0.037788-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter A. W., Talalay P. (1968). Studies on the microbiological degradation of steroid ring A. J. Biol. Chem. 243, 3238–3247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy S. K., Allemand D., Weis V. M. (2012). Cell biology of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 229–261. 10.1128/MMBR.05014-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca G., Ventura I., Sanghez V., Russo M. T., Ajmone-Cat M. A., Cacci E., et al. (2013). Prolonged lifespan with enhanced exploratory behavior in mice overexpressing the oxidized nucleoside triphosphatase hMTH1. Aging Cell 12, 695–705. 10.1111/acel.12094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rienzo F., Gabdoulline R. R., Wade R. C., Sola M., Menziani M. C. (2004). Computational approaches to structural and functional analysis of plastocyanin and other blue copper proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61, 1123–1142. 10.1007/s00018-004-3181-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D., Bateman A., Clements J., Coggill P., Eberhardt R. Y., Eddy S. R., et al. (2014). Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D222–D230. 10.1093/nar/gkt1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin M. Y., Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Koonin E., V (2015). Expanded microbial genome coverage and improved protein family annotation in the COG database. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D261–D269. 10.1093/nar/gku1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick B. R. (2012). Plant growth-promoting bacteria: mechanisms and applications. Scientifica (Cairo). 2012, 1–15. 10.6064/2012/963401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissa I., Vergnaud G., Pourcel C. (2007). CRISPRFinder: a web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W52–W57. 10.1093/nar/gkm360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosdent N., Maridonneau-Parini I., Sory M. P., Cornelis G. R. (2002). Role of Yops and adhesins in resistance of Yersinia enterocolitica to phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 70, 4165–4176. 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4165-4176.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillard R. R., Ryther J. H. (1962). Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 8, 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Sikorski J., Lapidus A., Nolan M., Glavina Del Rio T., Tice H., et al. (2009). Complete genome sequence of Kangiella koreensis type strain (SW-125). Stand. Genomic Sci. 1, 226–233. 10.4056/sigs.36635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmrich G., Bosch T. C. G. (2008). Compagen, a comparative genomics platform for early branching metazoan animals, reveals early origins of genes regulating stem-cell differentiation. Bioessays 30, 1010–1018. 10.1002/bies.20813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi M., Hayashi T., Kudo T. (2012). Steroid degradation in Comamonas testosteroni. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 129, 4–14. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutagalung A. H., Novick P. J. (2011). Role of Rab GTPases in membrane traffic and cell physiology. Physiol. Rev. 91, 119–149. 10.1152/physrev.00059.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt D., Chen G.-L., Locascio P. F., Land M. L., Larimer F. W., Hauser L. J. (2010). Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11:119. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun D. W., Shin N. R., Kim M. S., Oh S. J., Kim P. S., Whon T. W., et al. (2014). Endozoicomonas atrinae sp. nov., isolated from the intestine of a comb pen shell Atrina pectinata. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64, 2312–2318. 10.1099/ijs.0.060780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa J., Tsuchimoto D., Oka S., Ohno M., Furuichi M., Sakumi K., et al. (2008). Oxidation of mitochondrial deoxynucleotide pools by exposure to sodium nitroprusside induces cell death. DNA Repair (Amst.) 7, 418–430. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H., Yim J. H., Lee C., Choi S.-H., Park Y. K., Yoon S. H., et al. (2005). Genomic blueprint of Hahella chejuensisjeong, a marine microbe producing an algicidal agent. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 7066–7073. 10.1093/nar/gki1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A. D., Swanson M. S. (2011). Secrets of a successful pathogen: Legionella resistance to progression along the autophagic pathway. Front. Microbiol. 2:138. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juris S. J., Rudolph A. E., Huddler D., Orth K., Dixon J. E. (2000). A distinctive role for the Yersinia protein kinase: actin binding, kinase activation, and cytoskeleton disruption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9431–9436. 10.1073/pnas.170281997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käll L., Krogh A., Sonnhammer E. L. L. (2007). Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction-the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 429–432. 10.1093/nar/gkm256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp P. D., Riley M., Saier M., Paulsen I. T., Paley S. M., Pellegrini-Toole A. (2000). The EcoCyc and MetaCyc databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 56–59. 10.1093/nar/28.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katharios P., Seth-Smith H. M. B., Fehr A., Mateos J. M., Qi W., Richter D., et al. (2015). Environmental marine pathogen isolation using mesocosm culture of sharpsnout seabream: striking genomic and morphological features of novel Endozoicomonas sp. Sci. Rep. 5:17609. 10.1038/srep17609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel C. D., Meyer E., Matz M. V. (2013). Gene expression under chronic heat stress in populations of the mustard hill coral (Porites astreoides) from different thermal environments. Mol. Ecol. 22, 4322–4334. 10.1111/mec.12390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. H., Lee Y., Kim S., Yeom J., Yeom S., Kim B. S., et al. (2006). The role of periplasmic antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase and thiol peroxidase) of the Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the formation of biofilms. Proteomics 6, 6181–6193. 10.1002/pmic.200600320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimes N. E., Grim C. J., Johnson W. R., Hasan N. A., Tall B. D., Kothary M. H., et al. (2012). Temperature regulation of virulence factors in the pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus. ISME J. 6, 835–846. 10.1038/ismej.2011.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov F. A., Koonin E. V., Morgunov I. G., Finogenova T. V., Kondrashova M. N. (2006). Evolution of glyoxylate cycle enzymes in Metazoa: evidence of multiple horizontal transfer events and pseudogene formation. Biol. Direct 1:31. 10.1186/1745-6150-1-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S., Hirakawa H., Tabata S. (2015). GMcloser: closing gaps in assemblies accurately with a likelihood-based selection of contig or long-read alignments. Bioinformatics 31, 3733–3741. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krendel M., Mooseker M. S. (2005). Myosins: tails (and heads) of functional diversity. Physiology (Bethesda). 20, 239–251. 10.1152/physiol.00014.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzywinski M., Schein J., Birol I., Connors J., Gascoyne R., Horsman D., et al. (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645. 10.1101/gr.092759.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullander K., Klein R. (2002). Mechanisms and functions of eph and ephrin signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 475–486. 10.1038/nrm856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurahashi M., Yokota A. (2007). Endozoicomonas elysicola gen. nov., sp. nov., a γ-proteobacterium isolated from the sea slug Elysia ornata. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 30, 202–206. 10.1016/j.syapm.2006.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Q., Li W., Shao Z. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Alcanivorax dieselolei type strain B5. J. Bacteriol. 194, 6674. 10.1128/JB.01813-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Q., Shao Z. (2012). Genome sequence of the alkane-degrading bacterium Alcanivorax hongdengensis type strain A-11-3. J. Bacteriol. 194, 6972. 10.1128/JB.01849-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang T., Hansson G. C., Samuelsson T. (2007). Gel-forming mucins appeared early in metazoan evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 16209–16214. 10.1073/pnas.0705984104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T. M., Eddy S. R. (1997). tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964. 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A., Van Dyke M., Stock J. (1991). Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252, 1162–1164. 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A., Lu S., Anderson J. B., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M. K., DeWeese-Scott C., et al. (2011). CDD: a conserved domain database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D225–D229. 10.1093/nar/gkq1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon J. P., Moran N. A. (2011). Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 13–26. 10.1038/nrmicro2670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuckin M. A., Lindén S. K., Sutton P., Florin T. H. (2011). Mucin dynamics and enteric pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 265–278. 10.1038/nrmicro2538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meikle P., Richards G. N., Yellowlees D. (1987). Structural determination of the oligosaccharide side chains from a glycoprotein isolated from the mucus of the coral Acropora formosa. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 16941–16947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza M., Güiza L., Martinez X., Caraballo X., Rojas J., Aranguren L. F., et al. (2013). A novel agent (Endozoicomonas elysicola) responsible for epitheliocystis in cobia Rachycentrum canadum larvae. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 106, 31–37. 10.3354/dao02636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer E., Aglyamova G. V., Wang S., Buchanan-Carter J., Abrego D., Colbourne J. K., et al. (2009). Sequencing and de novo analysis of a coral larval transcriptome using 454 GSFlx. BMC Genomics 10:219. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. L., Paul V. J., Teplitski M. (2014). Community shifts in the surface microbiomes of the coral Porites astreoides with unusual lesions. PLoS ONE 9:e100316. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow K. M., Bourne D. G., Humphrey C., Botté E. S., Laffy P., Zaneveld J., et al. (2015). Natural volcanic CO2 seeps reveal future trajectories for host-microbial associations in corals and sponges. ISME J. 9, 894–908. 10.1038/ismej.2014.188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers E. W., Sutton G. G., Delcher A. L., Dew I. M., Fasulo D. P., Flanigan M. J., et al. (2000). A whole-genome assembly of Drosophila. Science 287, 2196–2204. 10.1126/science.287.5461.2196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadalin F., Vezzi F., Policriti A. (2012). GapFiller: a de novo assembly approach to fill the gap within paired reads. BMC Bioinformatics 13(Suppl. 1):S8. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S14-S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki E. P., Burge S. W., Bateman A., Daub J., Eberhardt R. Y., Eddy S. R., et al. (2015). Rfam 12.0: updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D130–D137. 10.1093/nar/gku1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neave M. J., Michell C. T., Apprill A., Voolstra C. R. (2014). Whole-genome sequences of three symbiotic endozoicomonas strains. Genome Announc. 2, e00802–e00814. 10.1128/genomeA.00802-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijima M., Adachi K., Katsuta A., Shizuri Y., Yamasato K. (2013). Endozoicomonas numazuensis sp. nov., a gammaproteobacterium isolated from marine sponges, and emended description of the genus Endozoicomonas Kurahashi and Yokota 2007. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63, 709–714. 10.1099/ijs.0.042077-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonechnikov K., Golosova O., Fursov M. (2012). Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 28, 1166–1167. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., et al. (2004). UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierleoni A., Martelli P. L., Fariselli P., Casadio R. (2006). BaCelLo: a balanced subcellular localization predictor. Bioinformatics 22, 408–416. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike R. E., Haltli B., Kerr R. G. (2013). Description of Endozoicomonas euniceicola sp. nov. and Endozoicomonas gorgoniicola sp. nov., bacteria isolated from the octocorals Eunicea fusca and Plexaura sp., and an emended description of the genus Endozoicomonas. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63, 4294–4302. 10.1099/ijs.0.051490-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitulescu M. E., Adams R. H. (2010). Eph/ephrin molecules - a hub for signaling and endocytosis. Genes Dev. 24, 2480–2492. 10.1101/gad.1973910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polato N. R., Altman N. S., Baums I. B. (2013). Variation in the transcriptional response of threatened coral larvae to elevated temperatures. Mol. Ecol. 22, 1366–1382. 10.1111/mec.12163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston G. M. (2007). Metropolitan microbes: type III secretion in multihost symbionts. Cell Host Microbe 2, 291–294. 10.1016/j.chom.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pundhir S., Kumar A. (2011). SSPred: A prediction server based on SVM for the identification and classification of proteins involved in bacterial secretion systems. Bioinformation 6, 380–382. 10.6026/97320630006380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina J.-B., Tapiolas D., Willis B. L., Bourne D. G. (2009). Coral-associated bacteria and their role in the biogeochemical cycling of sulfur. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 3492–3501. 10.1128/AEM.02567-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha E. R., Selby T., Coleman J. P., Smith C. J., Rocha E. R., Selby T., et al. (1996). Oxidative stress response in an Anaerobe, Bacteroides fragilis: a role for catalase in protection against Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 178, 6895–6903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roder C., Bayer T., Aranda M., Kruse M., Voolstra C. R. (2015). Microbiome structure of the fungid coral Ctenactis echinata aligns with environmental differences. Mol. Ecol. 24, 3501–3511. 10.1111/mec.13251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roterman Y. R., Benayahu Y., Reshef L., Gophna U. (2015). The gill microbiota of invasive and indigenous Spondylus oysters from the Mediterranean Sea and northern Red Sea. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 7, 860–867. 10.1111/1758-2229.12315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rua C. P. J., Trindade-Silva A. E., Appolinario L. R., Venas T. M., Garcia G. D., Carvalho L. S., et al. (2014). Diversity and antimicrobial potential of culturable heterotrophic bacteria associated with the endemic marine sponge Arenosclera brasiliensis. PeerJ 2:e419. 10.7717/peerj.419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvioli A., Ghignone S., Novero M., Navazio L., Venice F., Bagnaresi P., et al. (2015). Symbiosis with an endobacterium increases the fitness of a mycorrhizal fungus, raising its bioenergetic potential. ISME J. 10, 130–144. 10.1038/ismej.2015.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoebel S., Cichy A. L., Goody R. S., Itzen A. (2011). Protein LidA from Legionella is a Rab GTPase supereffector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 17945–17950. 10.1073/pnas.1113133108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiker S., Martins dos Santos V. A. P., Bartels D., Bekel T., Brecht M., Buhrmester J., et al. (2006). Genome sequence of the ubiquitous hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium Alcanivorax borkumensis. Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 997–1004. 10.1038/nbt1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwibbert K., Marin-Sanguino A., Bagyan I., Heidrich G., Lentzen G., Seitz H., et al. (2011). A blueprint of ectoine metabolism from the genome of the industrial producer Halomonas elongata DSM 2581T. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1973–1994. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02336.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinzato C., Shoguchi E., Kawashima T., Hamada M., Hisata K., Tanaka M., et al. (2011). Using the Acropora digitifera genome to understand coral responses to environmental change. Nature 476, 320–323. 10.1038/nature10249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Yano K., Sugimoto S., Kitajima K., Lennarz W. J., Inoue S., et al. (2002). Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase, an enzyme involved in processing of free oligosaccharides in the cytosol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9691–9696. 10.1073/pnas.152333599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischer S., Reineck M., Söding J., Münder S., Böttger A. (2013). Eph receptors and ephrin class B ligands are expressed at tissue boundaries in Hydra vulgaris. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 57, 759–765. 10.1387/ijdb.130158ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth J., Cutforth T., Gelinas A. D., Bethoney K. A., Bard J., Harrison C. J. (2001). Crystal structure of an ephrin ectodomain. Dev. Cell 1, 83–92. 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00002-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tout J., Siboni N., Messer L. F., Garren M., Stocker R., Webster N. S., et al. (2015). Increased seawater temperature increases the abundance and alters the structure of natural Vibrio populations associated with the coral Pocillopora damicornis. Front. Microbiol. 6:432. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trench R. K. (1979). The cell biology of plant-animal symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 30, 485–531. 10.1146/annurev.pp.30.060179.002413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twan W. H., Hwang J. S., Lee Y. H., Wu H. F., Tung Y. H., Chang C. F. (2006). Hormones and reproduction in scleractinian corals. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 144, 247–253. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzulli L., Pezzati E., Huete-Stauffer C., Pruzzo C., Cerrano C. (2013). 16SrDNA Pyrosequencing of the Mediterranean Gorgonian Reveals a link among alterations in Bacterial Holobiont Members, Anthropogenic Influence and disease outbreaks. PLoS ONE 8:e67745. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visick K. L., Ruby E. G. (1998). The periplasmic, group III catalase of Vibrio fischeri is required for normal symbiotic competence and is induced both by oxidative stress and by approach to stationary phase. J. Bacteriol. 180, 2087–2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Zetterstrom C. E., Gabrielsen M., Beckham K. S. H., Tree J. J., Macdonald S. E., et al. (2011). Identification of Bacterial target proteins for the Salicylidene Acylhydrazide class of virulence-blocking compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 29922–29931. 10.1074/jbc.M111.233858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore S. E., Lamont R. J. (2012). Tyrosine phosphorylation and bacterial virulence. Int. J. Oral Sci. 4, 1–6. 10.1038/ijos.2012.6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. (2001). Preparation of genomic DNA from bacteria. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 2; Unit 2.4. 10.1002/0471142727.mb0204s56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. J., Seib K. L., Edwards J. L., Apicella M. A., McEwan A. G., Jennings M. P. (2005). Azurin of pathogenic Neisseria spp. is involved in defense against hydrogen peroxide and survival within cervical epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 73, 8444–8448. 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8444-8448.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Fialho A. M., Punj V., Bratescu L., Gupta T. K., Chakrabarty A. M. (2005). Internalization of bacterial redox protein azurin in mammalian cells: entry domain and specificity. Cell. Microbiol. 7, 1418–1431. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. S., Chen M. H., Arun A. B., Chen C. A., Wang J. T., Chen W. M. (2010). Endozoicomonas montiporae sp. nov., isolated from the encrusting pore coral Montipora aequituberculata. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60, 1158–1162. 10.1099/ijs.0.014357-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J., Li L., Shaw N., Li Y., Song J. K., Zhang W., et al. (2009). Structural basis and catalytic mechanism for the dual functional endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase A. PLoS ONE 4:e4658. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Liang Y., Lynch K. H., Dennis J. J., Wishart D. S. (2011). PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W347–W352. 10.1093/nar/gkr485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.