Abstract

The variable presentation and progression of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) can make it difficult to recognize, particularly in adults. To improve diagnosis, a retrospective chart review was conducted on patients who were diagnosed as adults and/or were followed for several years after diagnosis. We present 5 cases that illustrate changes in LGS features over time. Cases 1 and 2 were diagnosed by age 8 with intractable seizures, developmental delay, and abnormal EEGs with 1.5–2 Hz SSW discharges. However, seizure type and frequency changed over time for both patients, and the incidence of SSW discharges decreased. Cases 3, 4, and 5 were diagnosed with LGS as adults based on current and past features and symptoms, including treatment-resistant seizures, cognitive and motor impairment, and abnormal EEG findings. While incomplete, their records indicate that an earlier LGS diagnosis may have been missed or lost to history. These cases demonstrate the need to thoroughly and continuously evaluate all aspects of a patient's encephalopathy, bearing in mind the potential for LGS features to change over time.

Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalogram; LGS, Lennox–Gastaut syndrome; SSW, slow spike–wave discharge; SW, spike–wave discharge

Keywords: Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, LGS, Adult, Diagnosis, Symptoms, Features

1. Introduction

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS) is a severe, chronic epileptic encephalopathy that presents during childhood. As one of the most difficult epileptic disorders to identify and manage, it accounts for up to 10% of childhood epilepsies [1]. It has been estimated that up to 25% of LGS cases develop in previously healthy children for unknown reasons, but most cases are associated with a congenital abnormality or insult to the brain (e.g., injury, infection, and tumor) [1], [2], [3]. Seizures typically begin before age 8, with a peak between 3 and 5 years of age [3]. Although onset after age 8 is rare, LGS has been diagnosed into adolescence and adulthood [4], [5], [6]. The vast majority of children who develop LGS will continue to exhibit at least some of its features into adulthood.

Lennox–Gastaut syndrome has historically been characterized by multiple intractable seizure types (tonic, atypical absence, and atonic “drop attacks” that often result in falls), cognitive impairment or regression with associated loss of skills and behavioral problems (hyperactivity, aggression, and depression), and abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG) findings of generalized 1.5–2.5 Hz slow spike–wave (SSW) complexes [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Despite the identification of these associated features, LGS can be difficult to diagnose because of the lack of specific biological markers, multiple etiologies, and varied presentation of features at onset [3], [11], [12]. In addition, the potential of features to evolve over time further complicates the recognition of LGS, particularly in adults [6], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18].

To clarify and improve diagnosis in adults, we present 5 cases that illustrate the evolution of LGS features and challenges in diagnosis.

2. Cases

2.1. Case 1 (M)

Case 1 was diagnosed with LGS at age 8 with intractable seizures, cognitive and visual impairment, and EEG showing generalized 1.5–2 Hz SSW discharges (Table 1 and Fig. 1, Panel A). Patient history included Group B streptococcal meningoencephalitis in early infancy resulting in severe encephalomalacia. By 6 weeks of age, he had partial multifocal seizures and EEG findings of right frontal and bioccipital spikes and ictal discharges. By 7 months of age, he had infantile spasms (IS) and possible hypsarrhythmia with global delay and visual impairment. An EEG at 20 months showed right temporo–parietal spikes, left occipital area attenuation, and slow occipital rhythm. By 3–4 years of age, the patient had atonic, tonic, and atypical absence seizures, and an EEG at age 6 showed multifocal spikes with generalized spike–wave and polyspike–wave discharges.

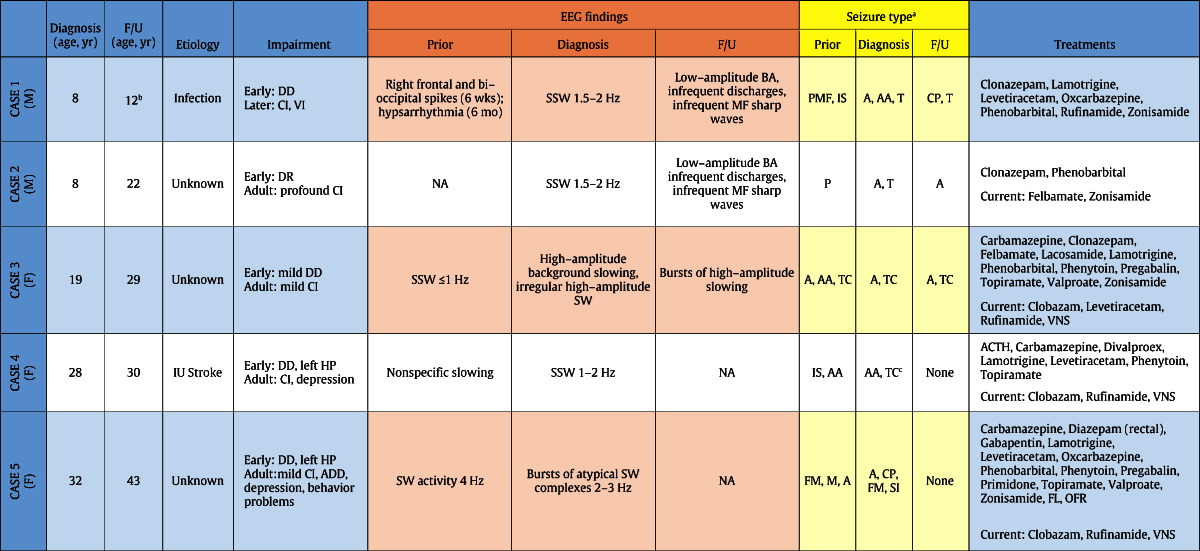

Table 1.

Summary of LGS features over time in case series.

ACTH indicates adrenocorticotropic hormone; BA, background activity; CI; cognitive impairment; DD, developmental delay; DR, developmental regression; F, female; FL, frontal lobectomy; F/U, follow-up; HP, hemiparesis; IU, intrauterine; M, male; mo, months; NA, information not available; None, the symptom or feature was not present; OFR, orbital frontal resection; SSW, slow spike–wave discharges; SW, spike–wave discharges; VI, visual impairment; wks, weeks; and yr, year(s).

aSeizure types: A = atonic; AA = atypical absence; CP = complex partial; FM = focal motor; IS = infantile spasms; M = myoclonic; P = partial; PMF = partial multifocal; SI = startle-induced; T = tonic; TC = tonic–clonic.

bSudden unexpected death occurred at age 12.

cSeizures occurred when patient discontinued seizure treatment due to acute depression.

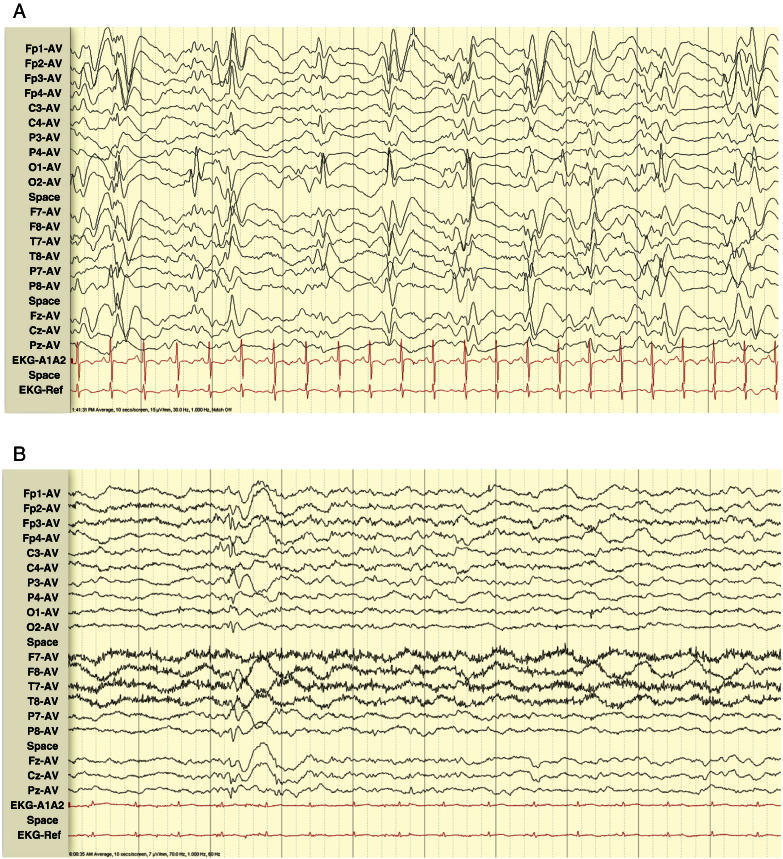

Fig. 1.

Panel A. Case 1, age 8. EEG at LGS diagnosis, showing generalized 1.5–2 Hz SSW discharges with frontal predominance, intermittent spike–waves predominating in the left occipital region, and poorly formed posterior rhythm.

Panel B. Case 1, age 12. EEG 4 years after diagnosis, showing low-amplitude background activity with infrequent low-amplitude generalized discharges and infrequent multifocal sharp waves.

Following LGS diagnosis at age 8 years, he had good but incomplete control of complex partial and generalized tonic seizures. Prior to sudden unexpected death (SUDEP) at age 12 years, EEG showed low-amplitude background activity, with infrequent low-amplitude generalized discharges and infrequent multifocal sharp waves (Fig. 1, Panel B). Treatments included clonazepam, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, rufinamide, and zonisamide in various combinations.

2.2. Case 2 (M)

Case 2 was diagnosed with LGS at age 8 years with cognitive impairment, tonic and atonic seizures, and abnormal EEG findings (Table 1). Patient history included developmental regression and partial seizures by 18 months of age, despite a normal birth and no history of brain injury or infection. Fourteen years after his LGS diagnosis (age 22 years), the patient could ambulate but had profound cognitive impairment with minimal verbal communication. His EEG showed low-amplitude background activity with infrequent low-amplitude generalized discharges and infrequent multifocal sharp waves. Having failed previous treatments including clonazepam and phenobarbital, his seizures were mostly controlled (with brief atonic seizures a couple of times a day) on felbamate and zonisamide.

2.3. Case 3 (F)

Case 3 was diagnosed with LGS when she presented at age 19 years with mild cognitive and speech impairment, seizures with frequent falls necessitating protective headgear, and abnormal EEG findings (Table 1 and Fig. 2, Panel A). Patient history was incomplete but included a normal birth followed by mild developmental delay and seizures of unknown etiology (first convulsive seizure was documented at age 9, with prior staring episodes suspected). Later in childhood, she had atypical absence, atonic, and tonic–clonic seizures. The EEG findings at age 12 showed generalized background slowing and ≤ 1 Hz SSW discharges (Fig. 2, Panel B). Treatments included carbamazepine, clonazepam, felbamate, lacosamide, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, pregabalin, topiramate, valproate, and zonisamide.

Fig. 2.

Panel A. Case 3, age 19. EEG at presentation and diagnosis, showing high-amplitude slowing with irregular high-amplitude generalized SW discharges.

Panel B. Case 3, age 12. EEG 7 years before diagnosis, showing generalized ≤ 1 Hz SSW discharges.

Panel C. Case 3, age 25. EEG 6 years after diagnosis, showing bursts of high-amplitude background slowing.

Six years after LGS diagnosis (age 25), EEG showed bursts of high-amplitude background slowing, indicating a decrease or disappearance of previously seen SSW discharges (Fig. 2, Panel C).

Ten years after diagnosis (age 29), seizure frequency had decreased such that protective headgear was no longer needed with clobazam, levetiracetam, rufinamide, and VNS.

2.4. Case 4 (F)

Case 4 was diagnosed with LGS when she presented at age 28 years with seizures (atypical absence and tonic–clonic), depression, cognitive impairment, mild left hemiparesis, and EEG findings of 1–2 Hz SSW discharges (Table 1). Patient history was incomplete but indicated intrauterine right hemispheric stroke with early left hemiparesis, IS, developmental delay, and EEG findings at an unspecified age of nonspecific slowing. Seizures had been mostly controlled with carbamazepine, divalproex, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or topiramate until she became depressed and discontinued her medications at age 28 and was hospitalized for seizures. After failing to achieve adequate seizure control with various treatment regimens (divalproex, levetiracetam, topiramate, and VNS), she is currently seizure-free on clobazam and rufinamide. She has intermittent problems with depression but continues to live independently with regular checks from her family.

2.5. Case 5 (F)

Case 5 was diagnosed with LGS at age 32 years when she presented with abnormal EEG findings (Fig. 3), intractable seizures (predominantly atonic but also complex partial, focal motor, and startle-induced), mild cognitive and motor impairment, mild left hemiparesis, depression, ADD, and behavioral issues. She was wheelchair-bound because of frequent falls with injury from seizures. Her medical records were incomplete but included exaggerated startle response from birth and early onset of seizures (unknown etiology), mild hemiparesis, and developmental delay. By age 4, she had focal motor and myoclonic seizures and EEG findings of diffuse right hemisphere slowing and 4 Hz SW discharges. She was diagnosed with epilepsy at age 7 and, by age 11, had learning problems, psychological issues, and EEG findings with intermittent right central–temporal slowing and bursts of SW activity. By age 19, she had atonic seizures.

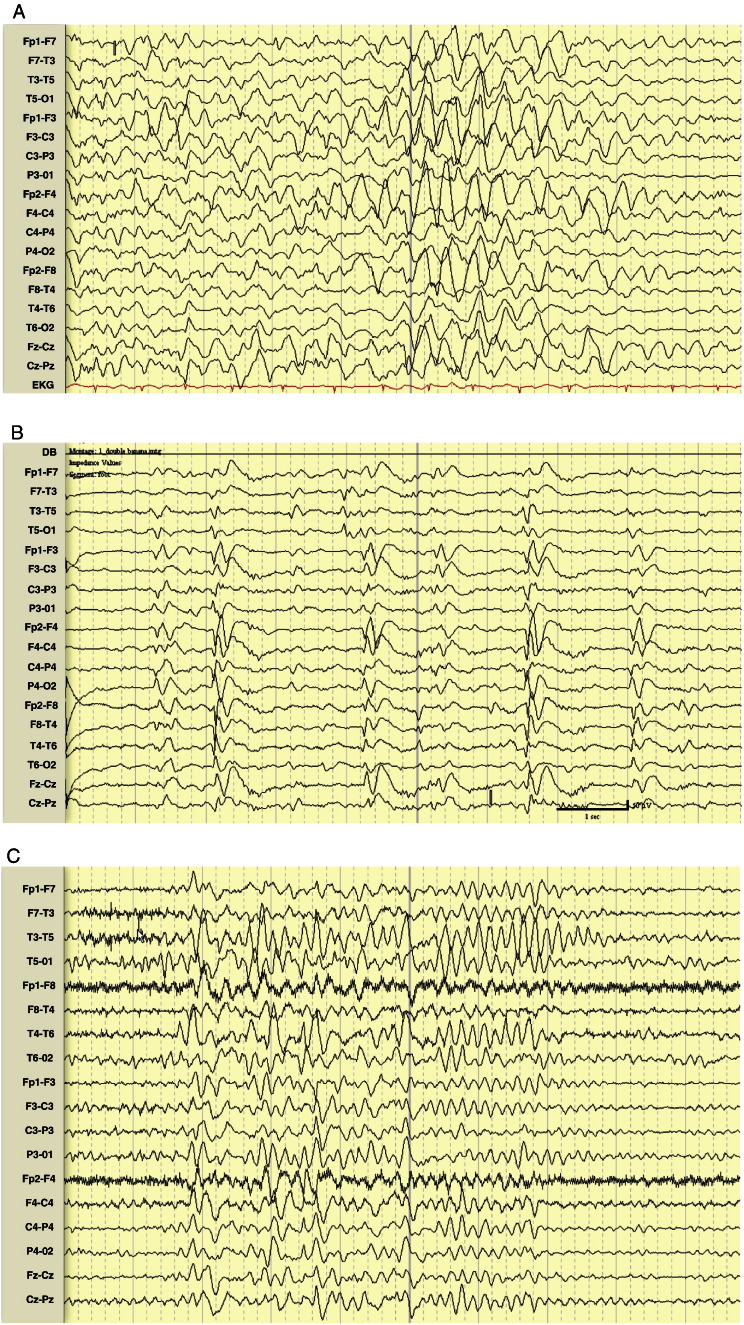

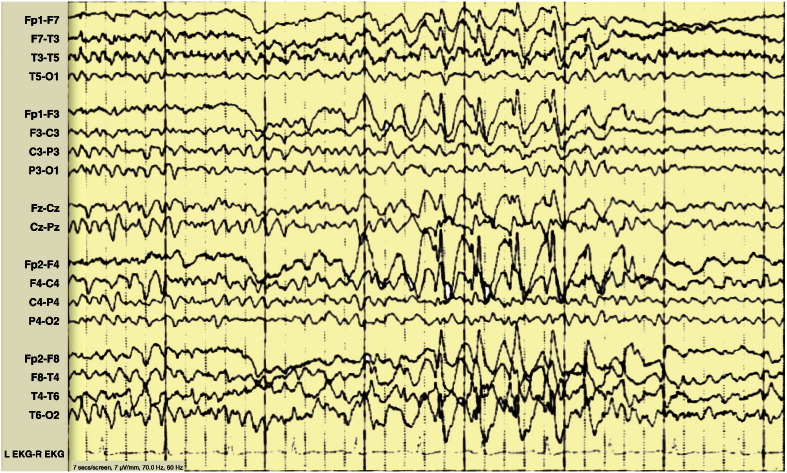

Fig. 3.

Case 5, age 32. EEG at presentation and diagnosis, showing irregular posterior dominant 4–7 Hz rhythm and bursts of atypical 2–3 Hz SW complexes.

Previous treatments included carbamazepine, diazepam (rectal), gabapentin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, pregabalin, primidone, topiramate, valproate, and zonisamide; also VNS, frontal lobectomy, and orbital frontal resection. She is currently seizure-free and has gone from using a wheelchair to a walker on a treatment regimen of rufinamide, clobazam, and VNS.

3. Discussion

Our cases illustrate the variable presentation and progression of LGS features (Table 1) and demonstrate how this changing nature can complicate diagnosis, particularly in adults who may not have complete records or for whom an earlier diagnosis may have been missed or lost to history. Cases 1 and 2 (2.1, 2.2) were diagnosed with LGS in early childhood with intractable seizures, developmental delay, and abnormal EEG findings with 1.5–2 Hz SSW complexes. In the years following diagnosis, the frequency and type of seizure changed for both patients, and the incidence of SSW discharges decreased or disappeared.

Cases 3, 4, and 5 (2.3, 2.4, 2.5) were diagnosed as adults with treatment-resistant seizures, cognitive and/or motor impairment, and abnormal EEG findings. Medical records for these patients were incomplete but included developmental delay, childhood onset of multiple seizure types, and abnormal EEGs, indicating that an earlier diagnosis may have been missed or lost to history.

Similar to previous retrospective studies [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], our cases had changes over time in seizure type/frequency and decreased incidence of SSW discharges. These changes may reflect response to treatment (i.e., medication effect), changes in brain plasticity during maturation, effects on the brain of prolonged electrical or epileptic activity, and/or sampling errors. The cases demonstrate the importance of continually reappraising clinical and EEG features in patients with epileptic encephalopathy and reevaluating therapeutic approaches and diagnoses. Given the changing nature of its features and symptoms, LGS should be considered in all adult patients with treatment-resistant seizures and cognitive impairment, especially those with a history of childhood onset of multiple seizure types.

Acknowledgments

Manuscript preparation, including writing, editing and formatting the manuscript, incorporating author comments, preparing tables and figures, and coordinating submission requirements, was provided by Jennifer Kaiser, PhD of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, IL). This editorial support was funded by Lundbeck.

Conflict of interest

This project was supported by funding from Lundbeck LLC.

Dr. Piña-Garza has served as a consultant and speaker for Cyberonics, Eisai Co., Ltd., Lundbeck LLC, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Supernus Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Upsher-Smith Laboratories and as a consultant for Allergan. He has received research grants from Eisai Co., Ltd. and UCB.

Dr. Chung has served as a consultant and speaker for Eisai Co., Ltd., Lundbeck LLC, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Upsher-Smith Laboratories and as a speaker for Cyberonics. He has received research support from Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., UCB Pharma, Lundbeck LLC, Upsher-Smith Laboratories, and SK Life Science, Inc.

Dr. Montouris has served as a consultant for Acorda Therapeutics, Inc., Eisai Co., Ltd., Lundbeck LLC, UCB, and Upsher-Smith Laboratories.

Dr. Radtke has served as consultant for Eisai Co., Ltd., Lundbeck LLC, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Supernus Pharmaceuticals, UCB, and Zynerba Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Dr. Resnick has served as a consultant for Lundbeck LLC, Eisai Co, Ltd., and Supernus Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. Wechsler has served as a consultant and speaker for Eisai Co., Ltd., Lundbeck LLC, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and UCB, a consultant for Upsher-Smith Laboratories, and a speaker for Cyberonics. He has been a clinical trial investigator for Alexza Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Eisai Co., Ltd., GW Pharmaceuticals plc, Lundbeck LLC, Marinus Pharmaceuticals, Inc., SK Life Science Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., UCB, and Upsher-Smith Laboratories.

Contributor Information

Jesus Eric Piña-Garza, Email: jeric.pina@gmail.com.

Steve Chung, Email: steve.chung@bannerhealth.com.

Georgia D. Montouris, Email: Georgia.Montouris@bmc.org.

Rodney A. Radtke, Email: rod.radtke@duke.edu.

Trevor Resnick, Email: Trevor.Resnick@mch.com.

Robert T. Wechsler, Email: wechsler5@me.com.

References

- 1.Camfield P.R. Definition and natural history of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl. 5):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock E.C., Cross H.H. Treatment of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD003277. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arzimanoglou A., Resnick T. All children who experience epileptic falls do not necessarily have Lennox–Gastaut syndrome… But many do. Epileptic Disord. 2011;13(Suppl. 1):S3–13. doi: 10.1684/epd.2011.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipinski C.G. Epilepsies with astatic seizures of late onset. Epilepsia. 1977;18(1):13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1977.tb05582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer G., Aichner F., Saltuari L. Epilepsies with diffuse slow spikes and waves of late onset. Eur Neurol. 1983;22(5):344–350. doi: 10.1159/000115581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerr M., Kluger G., Philip S. Evolution and management of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome through adolescence and into adulthood: are seizures always the primary issue? Epileptic Disord. 2011;13(Suppl. 1):S15–S26. doi: 10.1684/epd.2011.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gastaut H., Roger J., Soulayrol R., Saint-Jean M., Tassinari C.A., Regis H. Epileptic encephalopathy of children with diffuse slow spikes and waves (alias "petit mal variant") or Lennox syndrome. Ann Pediatr (Paris) 1966;13(8):489–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lennox W.G., Davis J.P. Clinical correlates of the fast and the slow spike–wave electroencephalogram. Pediatrics. 1950;5(4):626–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niedermeyer E. The Lennox–Gastaut syndrome: a severe type of childhood epilepsy. Dtsch Z Nervenheilkd. 1969;195(4):263–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00242459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Commission on classification and terminology of the international league against epilepsyEpilepsia. 1989;30(4):389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arzimanoglou A., French J., Blume W.T., Cross J.H., Ernst J.P., Feucht M. Lennox–Gastaut syndrome: a consensus approach on diagnosis, assessment, management, and trial methodology. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(1):82–93. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes J.R., Patil V.K. Long-term electro-clinical changes in the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome before, during, and after the slow spike–wave pattern. Clin Electroencephalogr. 2002;33(1):1–7. doi: 10.1177/155005940203300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohtsuka Y., Amano R., Mizukawa M., Ohtahara S. Long-term prognosis of the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Jpn J Psychiatry Neurol. 1990;44(2):257–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1990.tb01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogawa K., Kanemoto K., Ishii Y., Koyama M., Shirasaka Y., Kawasaki J. Long-term follow-up study of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome in patients with severe motor and intellectual disabilities: with special reference to the problem of dysphagia. Seizure. 2001;10(3):197–202. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferlazzo E., Nikanorova M., Italiano D., Bureau M., Dravet C., Calarese T. Lennox–Gastaut syndrome in adulthood: clinical and EEG features. Epilepsy Res. 2010;89(2–3):271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yagi K. Evolution of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome: a long-term longitudinal study. Epilepsia. 1996;37(Suppl. 3):48–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roger J., Remy C., Bureau M., Oller-Daurella L., Beaumanoir A., Favel P. Lennox–Gastaut syndrome in the adult. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1987;143(5):401–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaumanoir A. The Lennox–Gastaut syndrome: a personal study. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Suppl. 1982;35:85–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oguni H., Hayashi K., Osawa M. Long-term prognosis of Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 1996;37(Suppl. 3):44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb01820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]