Abstract

Background/Aim

Severe bone pain is experienced by 60–80% of patients with metastatic bone disease, and has a profound impact on quality of life. Therefore, effective pain relief is an important goal in managing metastatic bone disease. Orthopedic surgeons are often challenged with patients presenting with newly diagnosed bone metastases and severe and disabling bone pain. It is important to provide fast and sufficient analgesia. Clinical trials have demonstrated that bisphosphonates reduce effectively and sustained bone pain by approved standard dosage over time. Open label prospective trials have shown that short time high dose i.v. Ibandronate is effective in rapid pain relief in different primary tumors.

Patients and methods

In 33 patients with metastatic bone pain from newly diagnosed skeletal metastases we utilized the loading-dose concept for intravenous ibandronate (6 mg infused over 1 h on 3 consecutive days).

Results

In 33 patients loading-dose ibandronate therapy significantly reduced bone pain within the first 5–7 days (VAS day 0: 6–8 vs. day 7: 3–4). Only 3 patients showed no response concerning a distinct pain reduction within the first days of therapy. There was no increase in pain medication.

Conclusion

This clinical observational study in selected patients with severe metastatic bone pain undergoing an intensive high dosed ibandronate-therapy for a short period demonstrated that loading-dose ibandronate (6 mg i.v., 3 consecutive days) resulted in a reduction of pain within days.

Keywords: Bone metastases, Ibandronate, Bisphosphonate, Pain relief

1. Introduction

Tumor metastases of the skeleton occur in up to 80% of patients in progressed stages of cancer, most commonly in cases of breast, lung, prostate, kydney and thyroid tumors [1], [2]. Bone metastases are often associated with pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia and spinal cord compression, as well as severe bone pain [3]. Orthopedic surgeons are challenged with patients presenting with newly diagnosed bone metastases and severe and disabling pain. Skeletal pain is commonly divided in 3 groups: ongoing pain, incident breakthrough pain and movement-evoked breakthrough pain [4], [5]. Initially bone cancer patients most frequently suffer from ongoing pain, hurting as a dull, constant throbbing pain that intensifies with time [6]. In advanced stages of bone cancer extreme pain can occur spontaneously, or after weight-bearing or movement of the affected extremity [7]. Breakthrough pain is difficult to control, often high doses of opioids and non-steroidal drugs are required, accompanied by adverse effects like somnolence, cognitive impairment and constipation [4], [6]. Metastatic bone disease is a consequence of a tumorinduced imbalance of the activities of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Bisphosphonates have been shown to be a real alternative by reducing bone pain from metastases, probably by inhibiting the underlying processes of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption [1]. First- and second-generation bisphosphonates like clodronate or pamidronate, showed significant analgesic effects in patients with metastatic bone pain [8], [9]. In the need for rapid relief of severe metastatic bone pain, especially for breakthrough and opioid-resistent pain, without the negative side effects of opioids, the third generation bisphosphonate Ibandronate has been examined as a possible treatment option for patients suffering from metastatic breast cancer [2], [10], [11], [12]. A large multicenter study of patients with metastatic breast cancer evaluated the impact of intravenous Ibandronate on skeletal-related events and bone pain. Patients treated with 6 mg Ibandronate intravenously every 4 weeks for 2 years experienced significant reduction in bone pain compared to a control group [13]. Mancini et al. showed in 18 patients with metastatic bone disease, receiving a nonstandard treatment with 4 mg Ibandronate intravenously for 4 consecutive days significantly reduced bone pain scores within 7 days [2]. Patients attending orthopedic departments with newly diagnosed bone metastatic disease are in need of rapid pain relief before being transferred to further treatment modalities. Therefore, the purpose of this current study was to evaluate the short-term efficacy and safety of loading dose Ibandronate (6 mg intravenously administered for 3 consecutive days by a 1 h infusion) in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic bone disease of different primary tumors, suffering from severe bone pain.

2. Patients and methods

Thirty-three patients with symptomatic skeletal metastases from different tumor origins were treated with intravenous Ibandronate in an open, prospective, non-randomized study. The median age of patients was 59 years (33–78 yrs) (Table 1). All patients had radiologically confirmed bone metastases and were experiencing opioid resistant pain in site of the skeletal metastases. 23 patients described vertebral bone pain due to vertebral metastases, 3 patients complained about hip pain, 7 patients described all body pain. All of the patients were admitted due to the bone pain, for none of the patients an orthopedic operation was scheduled. None of the patients had received bone radiotherapy or bisphosphonate therapy previously. Furthermore, patients were excluded if they had moderate or severe hypercalcaemia (serum calcium >12 mg/dL), impaired renal function (serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dL), a change to their hormonal treatment or chemotherapy during 2 months before study entry.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Primary tumor | Age in yrs | Mean baseline VAS pain score | Mean VAS pain score at day 5–7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | 78 | 7 | 4 |

| Breast | 52 | 6 | 2 |

| Breast | 72 | 7 | 4 |

| Breast | 51 | 6 | 2 |

| Breast | 71 | 7 | 2 |

| Breast | 34 | 6 | 3 |

| Breast | 71 | 7 | 4 |

| Breast | 42 | 9 | 3 |

| Breast | 47 | 7 | 3 |

| Breast | 71 | 6 | 4 |

| Breast | 69 | 5 | 3 |

| Breast | 75 | 8 | 4 |

| Breast | 44 | 6 | 3 |

| Breast | 57 | 7 | 4 |

| Breast | 68 | 6 | 3 |

| Breast | 76 | 8 | 5 |

| Breast | 50 | 8 | 3 |

| Breast | 61 | 6 | 2 |

| Breast | 42 | 8 | 3 |

| Breast | 66 | 7 | 4 |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 69 | 7 | 5 |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 61 | 6 | 4 |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 51 | 7 | 3 |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 56 | 7 | 3 |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | 62 | 8 | 5 |

| Urothelium Carcinoma | 74 | 7 | 7 |

| Urothelium Carcinoma | 69 | 7 | 3 |

| Urothelium Carcinoma | 64 | 8 | 5 |

| Bronchial Carcinoma | 63 | 8 | 7 |

| Bronchial Carcinoma | 52 | 8 | 2 |

| Malignant Melanoma | 57 | 7 | 3 |

| Malignant Melanoma | 67 | 6 | 3 |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 33 | 7 | 3 |

During the study the patients received only Ibandronate plus opioids and non-steroidal antiphlogistic drugs. Patients were withdrawn from the study if they received other interventions that could have affected their level of pain. Ibandronate 6 mg was infused intravenously for 1 h on days 1, 2, 3 of the study. All patients were followed up until day 7 of the study. Physical examinations and assessments of vital signs were conducted on day 1 and every 2nd day thereafter. Efficacy variables included pain, and the use of analgesic. Bone pain was assessed using a visual analog scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable) [14]. Changes in pain severity during treatment were rated as improvement when the sum of decreases in pain scored between visits outweighed the sum of increases [10]. Indirect measurement of pain was received by using the Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (MEDD) index of opioid consumption. The MEDD is calculated as the daily morphine dose (in milligrams) multiplied by an MEDD factor of three for intravenous treatment, two for subcutaneous therapy or one for oral treatment [14]. Adverse events were monitored throughout the study (total of 7 days) and for 4 weeks after. Laboratory parameters reflecting renal function and serum calcium levels (Normal values, 8.5 to 10.3 mg/dl) were evaluated every day throughout study time.

Data for each assessment point are expressed as the mean value plus standard deviation. One tailed paired t-tests were performed to analyze the effects of ibandronate treatment. Significance level was set at p<0.05.

The trial had been approved by the institutional ethics committee.

3. Results

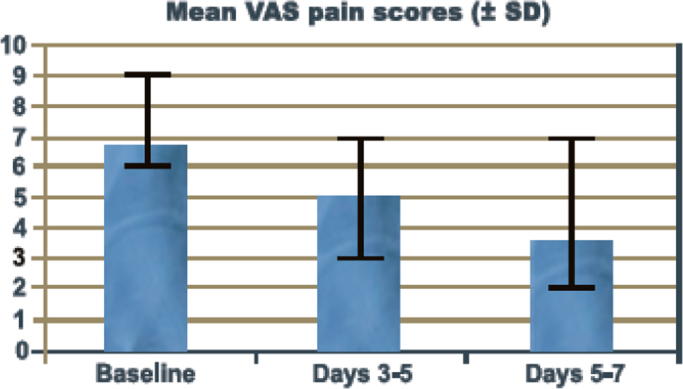

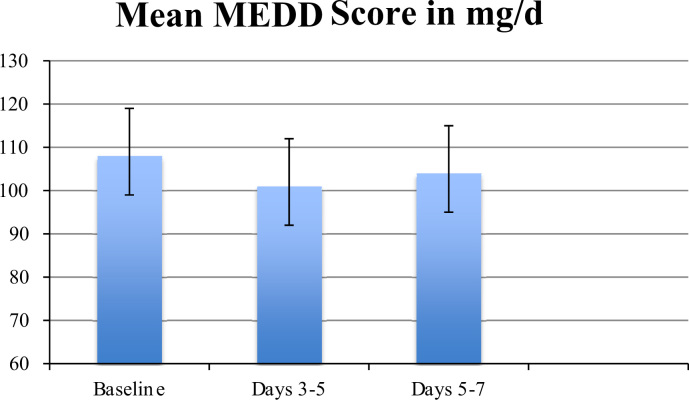

The study included 33 patients with a variety of different primary tumors (Table 1). The median age of patients was 59 years (33–78 yrs). The median duration of inpatient hospitalization before starting therapy was 1 day (0–2 days). All patients remained hospitalized until they were transferred to further treatment modalities (e.g. surgery, chemotherapy, radiation) with a median stay of 9 days (range 7–10 days). At day 0, all patients enrolled in the study were experiencing severe bone pain (mean visual analog pain score 6.8 (6–8)) while receiving an equivalent of 400 mg/d oral morphine. Pain intensity significantly decreased on day 3–5 (mean VAS 4.9 (3–7)) (p<0.01) and day 5–7 (mean VAS 3.7 (2–7)) (p<0.01) compared to day 0 (mean VAS 6.8 (6–8)) (Fig. 1). Significant reductions from baseline in visual analog pain scores while receiving ibandronate were not based on an increased use of other analgetics. None of the patients showed an increase in MEDD index throughout the study period (Fig. 2). Only one patient not responding to Ibandronate needed additional analgesic measures with regularly used fentanyl patches. Side effects consisted mainly of fever on the day following the first intravenous application of Ibandronate in 9 patients. One patient experienced a flu-like syndrome (fever, myalgia) that lasted for 48 h. No therapy was discontinued due to adverse side effects. Renal function and serum calcium levels (medium serum Calcium of 9.2 mg/dl at day 0 (range: 8.3 to 10.1), medium serum Calcium of 8.8 mg/dl at day 7 (range 8.1–9.9)) were in the physiological range in every measurement.

Fig. 1.

: Mean VAS pain scores.

Fig. 2.

Mean MEDD Index.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we were able to show that the administration of loading-dose Ibandronate therapy (60 mg Ibandronate infused intravenously over 1 h for 3 consecutive days) resulted in a highly significant decrease in pain levels in patients suffering from metastatic bone disease. Pain reduction was rapidly seen, within 3–5 days after the first infusion and accompanied by a substantial reduction in analgesic use.

As with any open-label study, it is possible that a placebo effect may have contributed to patients analgesia after initiation of the therapy. A randomized placebo-controlled trial would be required to finally prove the high analgesic effect of the loading-dose treatment with Ibandronate in metastatic bone disease. However, our results are consistent with previous reports. Two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter studies examined the efficiency of oral Ibandronate in bone pain relief. These studies were conducted with near-identical protocols, allowing data to be pooled [15], [16], [17]. 564 patients with metastatic bone disease due to breast cancer were randomised to receive oral Ibandronate 50 mg (n=287) or placebo (n=277) once daily. In contrast to placebo, Ibandronate rapidly reduced bone-pain scores. With placebo, bone-pain scores did not change for 36 weeks and then steadily increased over the next 60 weeks. After 60 weeks the difference in bone-pain score was significant comparing both groups (p=0.001). Mean analgesic use increased in both groups, but this increase was significantly less in the Ibandronate group (p=0.019) [16], [17]. In a small open-label pilot study of 18 patients with severe bone pain due to metastatic bone disease, short-term and intensive treatment with Ibandronate intravenously showed to have a high analgetic effect. Ibandronate 4 mg was infused for 2 h for 4 consecutive days. Within 7 days bone pain scores were significantly reduced, pain reduction was sustained over the whole study period of 6 weeks. Furthermore, improvements were seen in patients quality of life, patient functioning and performance status [2]. Altundag et al. observed in their phase II study of loading-dose Ibandronate treatment in patients with painful metastatic bone disease due to breast cancer a significant analgetic effect of the infused Ibandronate. 13 women with breast cancer, bone metastases and moderate/severe pain received 6 mg Ibandronate intravenously over 15 min over 3 consecutive days. During the follow-up period of 14 days pain level and analgesic use decreased significantly. Karnofsky performance index as a marker of functional impairment increased from day 0 (77.7) to day 14 (80.8). No renal safety concerns or other serious adverse effects were reported [12]. In 11 Austrian breast cancer patients with severe pain, insufficiently controlled by standard analgetics, an infusion of 6 mg Ibandronate i.v. for 3 consecutive days led to a significant decrease of pain (VAS<5) in all patients. Analgetic use was reduced within 3 days, and the WHO performance score was improved [18]. The reduction of bone pain under Ibandronate treatment has previously been observed in a phase III randomized trial of patients with bone metastases and breast cancer receiving 6 mg Ibandronte i.v every 3–4 weeks. A significant reduction in bone pain score was observed within 4 weeks after the first infusion with Ibandronate 6 mg compared to a placebo. The Ibandronate-receiving patients remained on decreased pain levels throughout the 2-year study period [13]. Currently, there are no head-to head trials comparing the efficacy of high intense loading-dose Ibandronate i.v. therapy regimen for metastatic bone pain versus other bsiphosphonates [12]. Barrett-Lee et al. compared the efficacy of oral ibandronic acid versus intravenous zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases from breast cancer in their open label, non-inferiority phase III trial. 705 patients received oral ibandronic acid 50 mg daily, 699 patients were treated with intravenous zoledronic acid at 4 mg every 3–4 weeks. Their results suggest that both drugs have acceptable side-effects and are options to prevent skeletal-related events caused by bone metastases. Pain scores showed a reduction in both study groups from baseline at 12 weeks, this reduction seemed to be maintained throughout the whole follow-up period of 96 weeks [18]. Compared to these results our data suggests that using a loading-dose treatment of Ibandronate in metastatic bone disease is associated with a faster reduction in bone pain compared to the standard therapeutic regimen. The intensive loading-dose regimen was not associated with any strong adverse effects. One patient experienced a flu-like syndrome (fever, myalgia) that lasted for 48 h. No renal or gastrointestinal side effects were noted. Parameters as hemotology, blood chemistry, urine analyses and renal function stayed in physiological levels for the whole follow-up period. These results are in line with former studies, where i.v. Ibandronate 6 mg has been shown not to be associated with attenuation in renal function [19]. Opioid-resistent bone pain is difficult to manage, fast and relieving therapeutical options are scarce but needed. Therefore, the loading-dose therapy with 6 mg Ibandronate i.v. may offer a promising new therapeutic modality for patients with severe metastatic bone pain. In the current study, we were able to demonstrate fast and safe analgetic effects of intensive Ibandronate therapy. The rapid improvement in patients pain level should improve these patients quality of life. The positive effects of loading-dose Ibandronate therapy seen in this study, needs further investigation in controlled clinical trials of opioid-resistent pain due to metastatic bone disease.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- 1.Body J.J., Mancini I. Bisphosphonates for cancer patients: why, how, and when? Support. Care Cancer. 2002;10:399–407. doi: 10.1007/s005200100292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mancini I., Dumon J.C., Body J.J. Efficacy and safety of ibandronate in the treatment of opioid-resistant bone pain associated with metastatic bone disease: a pilot study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22:3587–3592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janjan N. Bone metastases: approaches to management. Semin. Oncol. 2001;28:28–34. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halvorson K.G., Sevcik M.A., Ghilardi J.R., Sullivan L.J., Koewler N.J., Bauss F., Mantyh P.W. Intravenous ibandronate rapidly reduces pain, neurochemical indices of central sensitization, tumor burden, and skeletal destruction in a mouse model of bone cancer. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2008;36:289–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercadante S. Breakthrough pain: on the road again. Eur. J. Pain. 2009;13:329–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercadante S., Villari P., Ferrera P., Casuccio A. Optimization of opioid therapy for preventing incident pain associated with bone metastases. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2004;28:505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercadante S. Malignant bone pain: pathophysiology and treatment. Pain. 1997;69:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavlakis N., Schmidt R., Stockler M. Bisphosphonates for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005;3:CD003474. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003474.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tubiana-Hulin M., Beuzeboc P., Mauriac L., Barbet N., Frenay M., Monnier A., Pion J.M., Switsers O., Misset J.L., Assadourian S., Bessa E. [Double-blinded controlled study comparing clodronate versus placebo in patients with breast cancer bone metastases] Bull. Cancer. 2001;88:701–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diel I.J., Kurth A.H., Sittig H.B., Sittig H.B., Meden H., Maasberg M., Sandermann A., Bergner R. Bone pain reduction in patients with metastatic breast cancer treated with ibandronate-results from a post-marketing surveillance study. Support. Care Cancer. 2010;18:1305–1312. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidenreich A., Elert A., Hofmann R. Ibandronate in the treatment of prostate cancer associated painful osseous metastases. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2002;5:231–235. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altundag K., Dizdar O., Ozsaran Z., Ozkok O., Saip P., Eralp Y., Komurcu S., Kuzhan O., Ozguroglu M., Karahoca M. Phase II study of loading-dose ibandronate treatment in patients with breast cancer and bone metastases suffering from moderate to severe pain. Onkologie. 2012;35:254–258. doi: 10.1159/000338369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Body J.J., Diel I.J., Lichinitser M.R., Kreuser E.D., Dornoff W., Gorbunova V.A., Budde M., Bergström B., MF 4265 Study Group Intravenous ibandronate reduces the incidence of skeletal complications in patients with breast cancer and bone metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2003;4:1399–1405. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacox A., Carr D.B., Payne R. New clinical-practice guidelines for the management of pain in patients with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;330:651–655. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ringe J.D., Body J.J. A review of bone pain relief with ibandronate and other bisphosphonates in disorders of increased bone turnover. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2007;25:766–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Body J.J., Diel I.J., Lichinitzer A. Oral ibandronate reduces the risk of skeletal complications in breast cancer patients with metastatic bone disease: results from two randomised, placebo-controlled phase III studies. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;90:1133–1137. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Body J.J., Diel I.J., Bell R. Oral Ibandronate improves bone pain and preserves quality of life in patients with skeletal metastases due to breast cancer. Pain. 2004;11:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett-Lee P., Casbard A., Abraham J., Hood K., Coleman R., Simmonds P., Timmins H., Wheatley D., Grieve R., Griffiths G., Murray N. Oral ibandronic acid versus intravenous zoledronic acid in treatment of bone metastases from breast cancer: a randomised, open label, non-inferiority phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:114–122. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70539-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Moos R., Caspar C.B., Steiner R., Angst R., Inauen R., Schmieding K., Thürlimann B. Long-term renal safety profile of ibandronate 6 mg infused over 15 minutes. Onkologie. 2010;33:447–450. doi: 10.1159/000317256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]