Abstract

Background

The Ovarian Protection Trial In Premenopausal Breast Cancer Patients “OPTION” trial (NCT00427245) was a prospective, multicenter, randomised, open label study evaluating the frequency of primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) at 12 months in women randomised to 6–8 cycles of (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) +/− goserelin (G). Here we report the results of a secondary endpoint analysis of the effects of CT+/-G on markers of bone turnover.

Methods

Serum for bone alkaline phosphatase (BALP) and urine for N-terminal telopeptide (NTX) were collected at baseline, 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months. Changes in median levels of bone turnover markers were evaluated for the overall population, according to age stratification at randomisation (≤40 vs >40 years) and with exploratory analysis according to POI rates at 12 months.

Results

In the overall population, there was a significant increase in NTX at 6 months compared to baseline in patients treated with CT+G (40.81 vs 57.82 p=0.0074) with normalisation of levels thereafter. BALP was significantly increased compared to baseline at 6 months and 12 months in those receiving CT+G, but normalised thereafter. BALP remained significantly higher compared to baseline at 12, 24 and 36 months in patients receiving CT, resulting in a significant difference between treatment groups at 36 months (CT+G 5.845 vs CT 8.5 p=0.0006). These changes were predominantly seen in women >40 years. Women with POI at 12 months showed altered bone formation compared to baseline levels for a longer duration than women who maintained menses.

Conclusion

Addition of G to CT increases bone turnover during treatment with normalisation after cessation of treatment suggesting G may offer sufficient ovarian protection against CT induced POI to negate longstanding altered bone turnover associated with POI.

Keywords: Bone turnover markers, Primary ovarian insufficiency, Chemotherapy, Breast cancer, Goserelin

1. Introduction

Maintenance of bone health relies on a balance between bone formation by osteoblasts and bone resorption by osteoclasts. Under normal physiological circumstances, these two processes are tightly regulated to ensure preservation of the structural integrity of bone. However, cancer therapies can disrupt this delicate balance, leading to bone loss and subsequent increased fracture risk [1]. The pathophysiology of cancer treatment induced bone loss (CTIBL) is ascribed to either the direct effects of adjuvant treatments on bone turnover i.e. chemotherapy and endocrine therapy, or indirect effects via suppression of ovarian function with the subsequent low oestrogen environment causing clinically relevant bone loss [2].

Suppression of ovarian function in premenopausal women can be temporary or permanent dependent on the type of cancer treatment. The risk of POI is higher in women >40 years compared to 40 years or under [3] as loss of primordial follicles from direct chemotherapy toxicity depletes an already lowered ovarian reserve secondary to age [4]. Chemotherapy induces permanent primary ovarian insufficiency (POI) in 63–85% of patients receiving cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil (CMF) regimens and up to 50% with use of anthracycline containing regimens [5], [6] with effects on bone metabolism and bone mineral density (BMD) as a consequence. For example, following induction of permanent ovarian suppression by six cycles of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide chemotherapy, BMD fell at 6 months by 5.2% at the lumbar spine and by 2.8% at the femoral neck compared to baseline [7]. Bone loss associated with treatment induced ovarian failure appears to be more rapid and severe than the bone loss that occurs during a natural menopause, and therefore carries an increased risk of skeletal morbidity in long term survivors of premenopausal breast cancer [8]

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, such as goserelin, induce a rapid but reversible suppression of ovarian function with serum levels of oestradiol and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) reaching postmenopausal levels within 2 weeks of administration [9], [10]. In addition to the adjuvant use of goserelin in endocrine sensitive breast cancer, GnRH analogues have been evaluated in prospective randomized trials as a possible protection against chemotherapy induced POI in premenopausal women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Conflicting results have been reported with some studies demonstrating a reduction in chemotherapy induced early menopause of between 17% and 56% with addition of goserelin [11], [12], while others showed no statistical difference in resumption of menses post chemotherapy between those treated with or without goserelin [13], [14]. The impact of combined GnRH and chemotherapy on acute bone loss during therapy, and the delayed effects on bone post treatment have not been reported to date. Herein we present the secondary endpoint of bone turnover marker changes (serum bone alkaline phosphatase [BALP] and urine N-terminal telopeptide [NTX]) in the OPTION trial. The preliminary primary endpoint data of amenorrhoea rates at 12 months post chemotherapy were not statistically different between those treated with or without goserelin [14], although final data have not been reported yet.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Study population

The OPTION trial was an open, randomised multicenter study registered on the ClinialTrials.gov website, number NCT00427245. The trial was approved by South West Research Ethics Committee and performed in accordance with ICH GCP and the EU Directive. The primary objective was to evaluate the effect of goserelin on the incidence of POI at 12 months following chemotherapy in early breast cancer. All premenopausal ER negative women (or ER positive women for whom ovarian suppression was not considered necessary as part of the adjuvant therapy programme) recommended to receive (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy were eligible for inclusion. The average age of patients was 40. Women were stratified by age at randomisation (≤40 or >40 years) and by centre. Chemotherapy (CT) regimens comprised 6–8 cycles of cyclophosphamide and/or anthracycline and/or taxane. Goserelin (G) 3.6 mg by depot subcutaneous injection was randomly allocated to start before or at first chemotherapy cycle and continued 3–4 weekly until the final cycle of chemotherapy. At trial closure 227 patients had been randomised and all had given written informed consent for serum and urine analysis.

2.2. Patient evaluation

Secondary objectives of the OPTION trial included measurement of changes in bone turnover markers. Baseline serum and urine samples were available from 89 and 94 patients respectively. The serum and urine was stored at −80 °C pending batch analysis at Sheffield University’s Academic Unit of Bone Metabolism. Patients were excluded from this analysis if they did not have a follow up time point sample. Follow up time points were 6, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months post baseline. BALP was measured using the AcessÒ automated immunoassay, Beckman Coulter Inc (High Wycombe, United Kingdom). The inter assay coefficient of variation (CV)=5.2%. NTX and creatinine were measured using the Ortho Clinical Diagnostics automated immunoassay (High Wycombe, United Kingdom). The inter assay CV=4.4%. NTX was expressed as a ratio to creatinine and the inter assay CV for creatinine=1.8%.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Changes in median levels of bone turnover markers from baseline and between treatment groups were evaluated using the Mann Whitney u test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad PRISM v 6.0d. Significance was assigned at p≤0.05.

3. Results

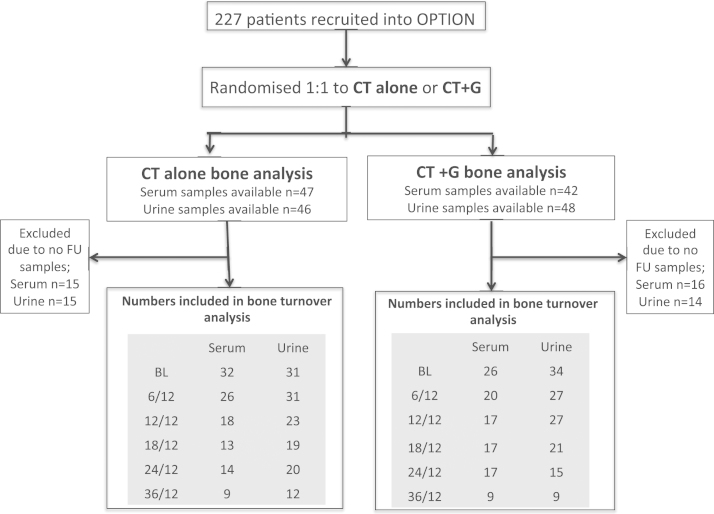

Of the 89 and 94 patients who provided serum and urine, 58 (serum) and 65 (urine) patients had at least one follow up sample and were included in the analyses (Fig. 1). The bone marker population had an average age of 38 years and predominantly ER positive tumours. The percentage of patients receiving anthracycline only (23%), anthracycline+cyclophosphamide (72%) or taxane (4%) chemotherapy was identical to the overall study population. Within this sub group treatment groups were well matched for age with a median (range) age of 41.5 years (30–51) in the CT alone group (n=54) and 41.0 years (26–49) in the CT+G group (n=54). Baseline BALP and NTX were similar between CT and CT+G groups with a median [IQR] BALP (μg/l) of 6.1 [4.9–7.9] and 6.3 [4.7–7.5] respectively and a median [IQR] NTX (nmol/mmol creatinine) of 33.9 [23.3–43.2] and 34.9 [28.8–47.2] respectively. Adjuvant tamoxifen use was similar between both groups (CT n=20, CT+G n=22).

Fig. 1.

Summary of patients included in the bone marker analysis.

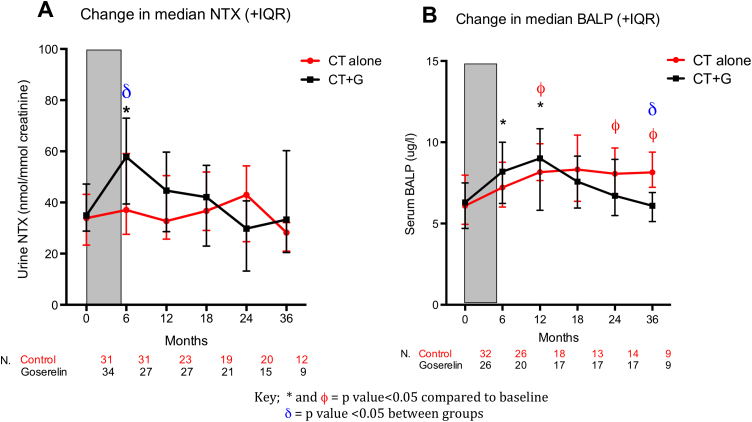

3.1. Bone resorption

Acute/on treatment median [IQR] NTX was significantly increased at 6 months (6/12) in patients treated with CT+G (6/12=57.8 [39.4–72.9] p=0.0030). This acute effect on bone resorption was not seen in patients treated with CT (37.07 [27.5–59.1]), resulting in a significantly higher NTX level at 6 months in the CT+G group compared with the CT group (p=0.0032) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Changes in bone resorption and bone formation markers in the overall study population.

Subsequently, following completion of G treatment at around 12–18 months, NTX returned to near baseline levels in the CT+G group with no significant differences from baseline at any further time point, indicating the acute G-induced increase in bone resorption resolved upon cessation of the drug. CT did not significantly change bone resorption compared to baseline at any time points.

3.2. Bone formation

Acute/on treatment median [IQR] BALP was significantly increased at 6/12 compared to baseline in patients treated with CT+G (baseline=6.3 [4.7–7.5], 6/12=8.2 [6.3–10.4] p=0.0174). This acute effect on bone formation was not seen in patients treated with CT (Fig. 2b).

Following completion of goserelin treatment, median [IQR] BALP remained significantly elevated compared to baseline at 12/12 in patients treated with CT+G (12/12= 9.2 [6.5–11.1] p=0.0043), and is likely to reflect a delayed coupling of bone formation to resorption following the increase in bone resorption induced by goserelin. BALP returned to baseline levels in patients treated with CT+G at all further time points with no significant difference compared to baseline. In patients treated with CT alone, BALP was significantly increased compared to baseline at 12/12 (8.1 [7.6–9.9] p=0.001), 24/12 (8.0 [6.8–9.6] p=0.0145) and 36/12 (8.2 [7.2–11.1] p=0.012) suggesting a delayed and lasting abnormality of bone turnover in this group.

3.3. Changes in bone turnover according to age stratification

In the main trial, patients were stratified according to age (≤40 or >40 years). We evaluated if age influenced the effects of treatment on bone turnover. In patients ≤40 years neither BALP or NTX changed significantly compared to baseline in either treatment group with the exception of NTX at a single time point (24/12) in the CT alone group; however, this is likely to be a chance finding in a small group of patients (Fig. 3A and B). In patients >40 the results mirrored the main bone marker analysis, with a significant increase in median [IQR] NTX in the CT+G group at 6/12 compared to baseline (baseline: 37.6 [30.4–50.7], 6/12: 59.1 [41.0–81.9], p= 0.0128). As in the main analysis, no change in NTX was seen in the CT group at 6/12 which resulted in a significant difference in NTX between treatment groups at this time point (CT+G; 59.1 [41.0–81.9], CT;37.7 [28.0–61.6] (p=0.0451)). The significant increase in median [IQR] BALP at 12/12 in CT+G patients was also seen (baseline 5.7 [4.6–7.5], 12/12 7.7 [6.3–10.5] p=0.0472) with a return to baseline levels at all further time points. The CT group again showed persistently significantly elevated BALP compared to baseline at 12/12 (p=0.0039) and 36/12 (p=0.013) resulting in a significantly higher BALP at 36/12 in the CT group compared to CT+G (p=0.017). These data suggest that the persistent alteration in bone turnover several years post completion of chemotherapy alone was largely restricted to those aged >40. This effect is not seen in women aged ≤40 treated with CT+G, who show early normalisation of bone turnover markers after completion of treatment by 12/12 (Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 3.

Changes in bone turnover markers according to age.

3.4. Exploratory analysis of changes in bone turnover according to POI at 12 months

Changes in bone markers over time were analysed in those patients for whom the primary endpoint data of POI at 12 months was known. Although median BALP levels were higher in amenorrhoeic women compared to menstruating women at 6/12 and 12/12, and median NTX was higher at 12/12 and 18/12 in amenorrheic women, the changes were not statistically significant between menstrual groups (Fig. 4A and B). However, in women who were amenorrheic median [IQR] BALP was significantly higher than baseline at 6/12 (baseline 5.6 [4.7–7.6], 6/12 7.8 [6.0–9.4] p=0.0063), 12 months (9.4 [7.6–11.5] p=<0.0001) and 18 months (7.6 [6.3–9.7] p=0.03), whereas women who maintained menstruation did not demonstrate a significant alteration in BALP during follow up (apart from a single time point (12/12) at which BALP was raised compared to baseline, although this may be a change finding as no other time points were significantly different to baseline). NTX was significantly raised compared to baseline in both menstruating (p=0.016) and amenorrhoeic (p=0.035) women at 6/12. These data suggest that women who experience POI at 12 months have altered bone formation that persists for at least 12 months post completion of adjuvant therapy. In addition, in women who developed POI at 12 months, the addition of goserelin to chemotherapy prevented long term alterations in BALP compared to chemotherapy alone after completion of adjuvant therapy (Fig. 5B), suggesting that sufficient ovarian function may be preserved to maintain normal bone turnover. However, the numbers of patients are small and the data should be considered exploratory.

Fig. 4.

Changes in bone turnover markers according to menstrual status at 12 months.

Fig. 5.

Treatment related changes in BALP according to menstrual status at 12 months.

4. Discussion

In this secondary endpoint analysis of the OPTION trial, we have shown that the addition of goserelin to neo(adjuvant) chemotherapy temporarily increased bone turnover during treatment and that this reverses over the next 6–12 months after completion of treatment. This is probably mediated by the effects on ovarian function, with a rapid and profound fall in oestradiol levels but, once the drug is stopped, ovarian function resumes to a level that is sufficient to maintain normal bone turnover, even if this is not manifested by a demonstrable difference in the frequency of chemotherapy induced amenorrhoea. We found no acute direct effect of chemotherapy on bone turnover markers, but there was a delayed effect on bone with increased bone turnover starting at 6 months after completion of chemotherapy and continuing throughout the 36 months of observation. This was predominantly in women aged >40 years and in those women who developed chemotherapy induced amenorrhoea, suggesting there may not be a direct toxic effect of chemotherapy on bone but that the BMD loss is driven predominantly by POI. Our study however has limitations that include a lack of ovarian function information beyond 12 months, which limits the interpretation of the association between bone markers and POI after this time point. In addition the number of serum/urine samples available for the bone marker analysis decreased during follow up thus limiting the interpretation of data at later time points.

We found that BALP remained persistently raised following completion of adjuvant therapy in women who experienced POI at 12 months, an effect not seen in menstruating women. Cameron et al. showed that BALP and serum CTX increased during chemotherapy in women who continue to menstruate (n=16) but normalised after cessation of treatment, whereas women who are amenorrheic (n=25) at the end of chemotherapy show a continuing rise in BALP [15], an observation that supports our findings. This altered bone turnover appears to persist and leads to evidence of bone loss at 5 years post chemotherapy that is more marked in women who develop amenorrhoea (lumbar spine BMD; −11.3%±0.9%) than those who maintain menses (lumbar spine BMD; −6.4%±1.2% respectively) [16].

In support of this, BMD loss following 6 months of CMF chemotherapy treatment in premenopausal breast cancer patients has been demonstrated at both the lumbar spine (−5.9%) and the femoral neck (−2%) at 2 years, with the largest changes in those patients who developed POI. [17]. Similarly, osteoporosis-free survival at 10 years following CMF chemotherapy is higher in menstruating women (100%) than those with irregular menses (69%) or amenorrhoea (67%) [18]. Therefore, patients with POI are at long term risk of bone loss.

This study has focused on the bone turnover markers NTX and BALP. In previous studies elevated NTX and BALP have been shown to correlate with risk of skeletal complications in patients with bone metastases from solid tumours and myeloma [19]. Moreover, clinical trials of anti-bone resorptive therapies i.e. bisphosphonates have demonstrated that lowering of bone turnover marker values to premenopausal levels reduces fracture risk [20], [21], [22]. Thus the persistent changes in bone turnover markers seen in our study have potential implications for subsequent fracture risk.

The effects of permanent and temporary ovarian suppression on bone have been evaluated in prospective breast cancer trials comparing chemotherapy to GnRH analogues in premenopausal women. Evaluation of BMD was undertaken in the bone sub-study of the ZEBRA trial (Zoladex in Early Breast Cancer Research Association) which compared 6x CMF with 2 years of goserelin; at 2 years BMD losses at lumbar spine and femoral neck compared to baseline were −10.5% and −6.4% with goserelin, and −6.5% and −4.5% with CMF [23]. However at 3 years (12 months after completion of goserelin) BMD at both anatomical sites partially recovered in the goserelin cohort compared to persistent loss in the CMF cohort. Amenorrhoea was observed in 100% of patients treated with goserelin and 64% treated with CMF at 2 years, however, there was resumption of menses in 73% of the goserelin group at 3 years but continued amenorrhoea in 76.5% CMF patients.

The acute effects of goserelin on bone have also been evaluated by prospective trials of goserelin+/− adjuvant tamoxifen. The Zoladex in Premenopausal Patients trial randomized 89 women with early breast cancer to goserelin+/− tamoxifen, tamoxifen alone and no endocrine therapy. After 2 years of treatment there was a significant reduction in BMD of 5% in patients receiving goserelin alone with partial recovery in BMD of 1.5% at 12 months post cessation of treatment [24].

The role of goserelin to protect against chemotherapy induced POI is controversial. However, the POEMS study recently reported preliminary results that are likely to increase the use of this therapeutic strategy [25]. POEMS randomised 257 premenopausal patients with ER-ve breast cancer to standard cyclophosphamide containing chemotherapy alone or with monthly goserelin 3.6 mg. The primary endpoint was 2 year POI with secondary endpoints that included survival and pregnancies. POI rates were 22% in standard arm and 8% in the goserelin arm (p=0.03). There were more pregnancies in the goserelin arm (22 vs 13 p=0.05). Remarkably in this ER-ve population, disease free and overall survival were also improved in the goserelin arm.

In conclusion, our data are the first to show that concomitant use of chemotherapy and goserelin may protect ovarian function sufficiently to prevent long term deleterious effects on bone turnover. In young women who experience POI as a result of chemotherapy it will be important that bone health assessment is carried out as part of their longer term follow up [26], [27].

Role of funding Source

The OPTION trial was sponsored by the Anglo Celtic Cooperative Oncology Group with funding received from Cancer Research UK, Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre and the National Institute of Health Research UK (grant number C4831/A181). Study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report and the decision to submit the article for publication was the responsibility of the authors with no involvement of the funding source.

Declaration of interest statement

DJA Adamson declares a close family member had shares in GSK and had personal access to research funding from Roche, Aventis, Norvartis, Amgen, Pfizer, Bayer, Sanofi-Aventis, Genetech, Boehringer, Ingelhein, Immodulon Therapeutics, Schering Plough and Astra Zeneca. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Caroline Wilson, Email: c.wilson@sheffield.ac.uk.

Fatma Gossiel, Email: f.gossiel@sheffield.ac.uk.

Robert Leonard, Email: r.leonard@imperial.ac.uk.

Richard A Anderson, Email: Richard.anderson@ed.ac.uk.

Douglas J A Adamson, Email: d.adamson@nhs.net.

Geraldine Thomas, Email: geraldine.thomas@imperial.ac.uk.

Robert E Coleman, Email: r.e.coleman@sheffield.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Coleman R.E., Rathbone E., Brown J.E. Management of cancer treatment-induced bone loss. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2013;9(6):365–374. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson C., Coleman R.E. Adjuvant therapy with bone-targeted agents. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care. 2011;5(3):241–250. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3283499c93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro C.L., Manola J., Leboff M. Ovarian failure after adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with rapid bone loss in women with early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2001;19(14):3306–3311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan S. How do chemotherapeutic agents damage the ovary? Hum. Reprod. Update. 2012;18(5):525–535. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lower E.E. The risk of premature menopause induced by chemotherapy for early breast cancer. J. Women’s Health Gend.-Based Med. 1999;8(7):949–954. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1.1999.8.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bines J., Oleske D.M., Cobleigh M.A. Ovarian function in premenopausal women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1996;14(5):1718–1729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadji P. The influence of chemotherapy on bone mineral density, quantitative ultrasonometry and bone turnover in pre-menopausal women with breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45(18):3205–3212. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman R. Bone health in cancer patients: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann. Oncol.: Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol./ESMO. 2014 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brogden R.N., Faulds D. Goserelin. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in prostate cancer. Drugs Aging. 1995;6(4):324–343. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199506040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonat W. Goserelin versus cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil as adjuvant therapy in premenopausal patients with node-positive breast cancer: the zoladex early breast cancer research association study. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20(24):4628–4635. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badawy A. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for prevention of chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage: prospective randomized study. Fertil. Steril. 2009;91(3):694–697. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Mastro L. Effect of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue triptorelin on the occurrence of chemotherapy-induced early menopause in premenopausal women with breast cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA: J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2011;306(3):269–276. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber B. Effect of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist on ovarian function after modern adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy: the GBG 37 ZORO study. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(17):2334–2341. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonard R.C., A.D., Anderson R. The OPTION trial of adjuvant ovarian protection by goserelin in adjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(suppl):15s. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron D.A. Bone mineral density loss during adjuvant chemotherapy in pre-menopausal women with early breast cancer: is it dependent on oestrogen deficiency? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010;123(3):805–814. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0899-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson R.A., Cameron D.A. Pretreatment serum anti-mullerian hormone predicts long-term ovarian function and bone mass after chemotherapy for early breast cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96(5):1336–1343. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saarto T. Chemical castration induced by adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil chemotherapy causes rapid bone loss that is reduced by clodronate: a randomized study in premenopausal breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 1997;15(4):1341–1347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vehmanen L.K. The effect of ovarian dysfunction on bone mineral density in breast cancer patients 10 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(1):75–79. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.792992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman R.E. Predictive value of bone resorption and formation markers in cancer patients with bone metastases receiving the bisphosphonate zoledronic acid. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(22):4925–4935. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarkar S. Relationship between changes in biochemical markers of bone turnover and BMD to predict vertebral fracture risk. J. Bone Miner. Res.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2004;19(3):394–401. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eastell R. Relationship of early changes in bone resorption to the reduction in fracture risk with risedronate. J. Bone Miner. Res.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2003;18(6):1051–1056. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer D.C. Change in bone turnover and hip, non-spine, and vertebral fracture in alendronate-treated women: the fracture intervention trial. J. Bone Miner. Res.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2004;19(8):1250–1258. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fogelman I. Bone mineral density in premenopausal women treated for node-positive early breast cancer with 2 years of goserelin or 6 months of cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil (CMF) Osteoporos. Int. (J. Establ. Result Cooperation Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA) 2003;14(12):1001–1006. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1508-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sverrisdottir A. Bone mineral density among premenopausal women with early breast cancer in a randomized trial of adjuvant endocrine therapy. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(18):3694–3699. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore H.C. Goserelin for ovarian protection during breast-cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372(10):923–932. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coleman R. Bone health in cancer patients: ESMO clinical practice guidelinesdagger. Ann. Oncol.: Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol./ESMO. 2014;25(Suppl 3):iii124–iii137. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillner B.E. American society of clinical oncology 2003 update on the role of bisphosphonates and bone health issues in women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21(21):4042–4057. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]