Abstract

Procalcitonin (PCT) is a biomarker of inflammation that is used to help make clinical decisions, like starting antibiotics or admitting a patient to the hospital. While PCT levels have been widely studied in pneumonia, levels in less severe acute respiratory infections (ARI) have not been well studied. To measure PCT levels in otherwise healthy adults during ARI, we followed 99 healthy adults during the cold and flu season, collecting blood specimens for PCT testing at baseline, and when participants presented with ARI. Ninety-six percent of the ARI samples had PCT levels <0.05 ng/mL. The remaining 4% were <0.25 ng/mL. These data suggest that PCT is not a useful test in ARI of mild-to-moderate severity.

Background

Procalcitonin (PCT) is a biomarker of systemic inflammation. It acts in a way similar to inflammatory cytokines, but PCT rises and falls quickly in comparison to other inflammatory biomarkers (10). PCT is used in clinical settings as a biomarker of inflammation to aid in the determination of prognosis and treatment, especially in cases of bacteremia and pneumonia (13). Serum PCT is understood to be useful for predicting bacteremia, septicemia, septic shock, and other severe infections and conditions (3). In addition, it is used in the monitoring of therapeutic response to antibiotics and to make a differential diagnosis of bacterial versus viral infections in illnesses such as meningitis and pneumonia (5).

While PCT levels have been widely studied in pneumonia and other serious lower respiratory tract infections, less research has been done surrounding PCT levels in upper respiratory tract infections and in less severe acute respiratory infections (ARI) in general.

We followed 99 study participants during the cold and flu season (August 2012–May 2013) and collected blood specimens for PCT testing at three healthy time points (August, December, March) in addition to all time points at which a study participant presented with ARI illness. The results of this work are important for extending the knowledge about PCT and its applications as a clinically useful biomarker of infection severity and may help avoid the unnecessary use of PCT testing.

Objectives

The aim was to measure PCT levels in adults during ARI and at healthy time points to see if PCT levels are elevated with ARI.

Study Design

Participants

Data come from a randomized clinical trial measuring the effects of mindfulness meditation or exercise on the incidence and severity of ARI (Clinical Trials ID: NCT01654289). The study protocol was approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research. Study participants were community-recruited individuals between the age of 30 and 69 who reported getting on average at least one cold per year, but were otherwise generally healthy. Ninety-nine individuals were enrolled in the study during August and September 2012 after giving informed consent and exited the study in May and June 2013.

The clinical trial is ongoing and the investigators are still blinded. While it is known that people can influence the functioning of their immune system through exercise, meditation, breathing techniques, and exposure to cold, we believe it is unlikely the interventions of the randomized clinical trial could significantly influence PCT measurements (2,8).

ARI definition and monitoring

After providing written informed consent, participants were monitored once a week using a web-based surveillance system to self-report ARI episodes. To define the beginning of an ARI episode, three criteria had to be met: (i) Answer “Yes” to either “Do you think you have a cold?” or “Do you think you are coming down with a cold?”; (ii) Report at least one of four cold symptoms: Nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, sneezing, or sore throat; and (iii) Score at least two points on the Jackson scale. The Jackson score is calculated by summing scores for eight symptoms: sneezing, headache, malaise, chilliness, nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, sore throat, and cough. Each symptom is rated 0, 1, 2, or 3; from absent to severe (7). Throughout the duration of an ARI episode, data about symptom severity and quality of life impact were collected daily using the validated Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WURSS-24) (1).

Specimen collection and biomarker testing

Blood samples were collected at baseline (August/September), at two follow-up visits (December and March) and once during each ARI episode, within 72 h of onset of symptoms. Serum PCT concentrations were measured by UW Hospital and Clinics Laboratory using Biomerieux's enzyme-linked fluorescent assay methodology according to manufacturer's protocol. The PCT assays were done in batches and were not part of the participant's medical record. PCT concentration of <0.05 ng/mL was considered normal, 0.05–0.25 ng/mL clinically insignificant, and ≥0.26 ng/mL supportive of clinically significant infection. Nasal swab and wash specimens were collected during each ARI illness episode and assessed for respiratory viruses (adenoviruses, bocavirus, coronaviruses, enterovirus, influenza viruses, metapneumovirus, parainfluenzaviruses, rhinovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) using multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (9).

Results

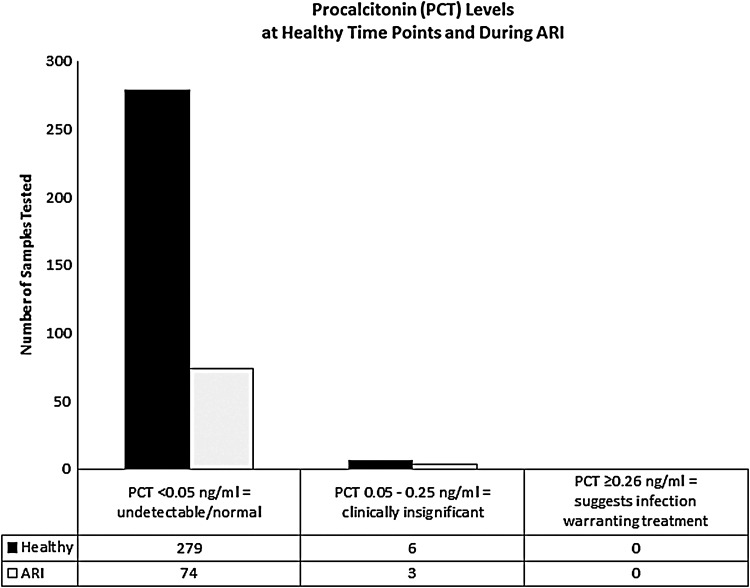

Of the 99 participants we followed, 63 participants had at least one ARI episode. There were a total of 97 ARI episodes as some participants had more than one ARI episode during the season (Table 1). Characteristics of the ARI episodes can be seen in Table 2. PCT levels were measured during 77 of the ARI episodes. We were unable to measure PCT levels during 20 of the ARI episodes due to challenges getting samples within 72 h of onset of symptoms, as required by protocol. Seventy-four of the PCT levels measured during ARI were <0.05 ng/mL and 3 were 0.05–0.24 ng/mL (n = 77). Two hundred eighty-five PCT measurements were obtained at healthy time points, while the included participants were symptom free. Of the PCT levels measured at healthy time points, 279 were <0.05 ng/mL and 6 were 0.05–0.24 ng/mL (n = 285) (Fig. 1). PCT data from 12 non-ARI visits were missing.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Number of participants | 99 | ||

| Mean age | 50 ± 11 years | ||

| Gender | 24 male (24%) | 75 female (76%) | 0 other (0%) |

| Participants who reported ARI | 63 reported ≥1 ARI (64%) | 36 reported no ARI (36%) |

ARI, acute respiratory infection.

Table 2.

Acute Respiratory Infection Characteristics

| ARI episodesa | 97 | |

| Mean ARI duration | 9.7 ± 9.3 days | |

| Mean AUCb | 304 ± 364.4c | |

| Missed work | ARI episodes resulting in missed work | 35 (39%) |

| Total missed work | 457 h (∼57 days) | |

| Healthcare visits | ARI episodes resulting in a healthcare visit | 11 (12%) |

| Total healthcare visits | 18 | |

| Antibiotic prescriptions | 5 | |

| Hospitalizations | 0 | |

Duration and severity data are missing for 8 of the 97 Jackson documented ARI episodes.

Duration versus WURSS score.

Value corresponds to mild-to-moderate severity.

AUC, area under curve; WURSS, Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey.

FIG. 1.

Column chart shows PCT levels measured at healthy time points (n = 285) and during ARI (n = 77). None of the PCT levels, including during ARI and at healthy time points, was ≥0.26 ng/mL; none reached clinical significance. ARI, acute respiratory infection; PCT, procalcitonin.

Of the three ARI and six non-ARI PCT results ≥0.05 ng/mL, all were clinically insignificant at <0.25 ng/mL. Of those non-ARI PCT results ≥0.05, two were at baseline (0.07 and 0.08 ng/mL), two were at the December visit (0.1 and 0.08 ng/mL), and two were at the March visit (0.15 and 0.11 ng/mL). The ARI results ≥0.05 were 0.05, 0.05, and 0.12 ng/mL. The participant with 0.12 ng/mL PCT during ARI had PCT in the same range at all three healthy visits. The other two participants with measureable PCT during ARI had no notable characteristics with their ARI compared to other ARI episodes in the study. One had RSV identified, but there were five other RSV infections that did not induce measurable PCT. Neither required antibiotics nor did they utilize any healthcare services.

In the entire dataset, including both ARI and non-ARI, none of the PCT levels was ≥0.25 ng/mL; none reached clinical significance. The PCT results were not available to the participant's clinician, so it would not have influenced treatment. Samples from 78 ARI episodes were tested for respiratory viruses using PCR. Of them, 50 resulted in a positive viral identification, while 28 were negative.

Discussion

PCT is a measure of a systemic inflammatory response seen with serious infections. PCT has a high negative predictive value (15). If PCT is negative, it is highly unlikely there is a systemic inflammatory reaction due to bacteria. PCT can be a useful tool for clinical decision-making on when to admit to the hospital or the intensive care unit, and when to start antibiotics (5,6,11,14). The PCT trend over time can be monitored to gauge clinical improvement of a bacterial infection. As the level drops, the prognosis improves (4).

Our data show that PCT is not elevated during common community-acquired ARI. Generally ARIs are mild-to-moderate in severity, requiring neither healthcare services nor prescription medications, and are often viral in etiology. Even though PCT production is known to be stimulated by cytokines typically elevated during ARI (IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, and TNFα), and by bacterial products, our results do not show elevation of PCT during ARI.

One weakness of this study is that we do not have data about potential bacterial causes of infection in the ARI episodes we documented. However, only five antibiotic prescriptions were written. Even then, no confirmation of bacterial infection can be assured. Fifty-two percent of the documented ARIs resulted in positive viral identification by PCR. The etiology of the remaining 48% is unknown. The infections could be caused by a virus outside the scope of the multiplex assay used, or it could be bacterial or other (12). Regardless of the pathogen causing the ARI, participants did not produce clinically important levels of PCT.

In conclusion, our data support PCT as a useful test for excluding clinically important systemic infection. Our results show that PCT will likely be normal or below detection in patients with mild-to-moderate ARI. Our work adds further value to the appropriate use of assessing PCT levels on patient presentation in those with worrisome symptoms. The results of this work will help inform the research of investigators and clinical applications of PCT testing.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, USA (R01AT006970). Bruce Barrett was supported by a mid-career research and mentoring award from NCCIH (K24AT00654).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

All authors have made substantial contributions to (i) the study concept and design, and data analysis and interpretation, (ii) drafting and revision of the article, and (iii) final approval of the version to be submitted.

References

- 1.Barrett B, Brown R, Mundt M, et al. The Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey is responsive, reliable, and valid. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:609–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett B, Hayney MS, Muller D, et al. Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:337–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker KL, Snider R, Nylen ES. Procalcitonin assay in systemic inflammation, infection, and sepsis: clinical utility and limitations. Crit Care Med 2008;36:941–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouadma L, Luyt C-E, Tubach F, et al. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients' exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:463–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christ-Crain M, Jaccard-Stolz D, Bingisser R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster-randomised, single-blinded intervention trial. Lancet 2004;363:600–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christ-Crain M, Müller B. Biomarkers in respiratory tract infections: diagnostic guides to antibiotic prescription, prognostic markers and mediators. Eur Respir J 2007;30:556–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson GG, Dowling HF, Muldoon RL., VII Present concepts of the common cold. Am J Public Health Nations Health 1962;52:940–945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kox M, van Eijk LT, Zwaag J, et al. Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:7379–7384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee W-M, Grindle K, Pappas T, et al. High-throughput, sensitive, and accurate multiplex PCR-microsphere flow cytometry system for large-scale comprehensive detection of respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:2626–2634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meisner M. Update on procalcitonin measurements. Ann Lab Med 2014;34:263–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michaelidis CI, Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy for outpatient management of acute respiratory tract infections in adults. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:579–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Musher DM, Bebko SP, Roig IL. Serum procalcitonin level, viral polymerase chain reaction analysis, and lower respiratory tract infection. J Infect Dis 2014;209:631–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider H-G, Lam QT. Procalcitonin for the clinical laboratory: a review. Pathology 2007;39:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuetz P, Christ-Crain M, Thomann R, et al. Effect of procalcitonin-based guidelines vs standard guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: the prohosp randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:1059–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ugajin M, Yamaki K, Hirasawa N, et al. Predictive values of semi-quantitative procalcitonin test and common biomarkers for the clinical outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Care 2013;59:564–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]