Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the association between the presence of integrated systems of stroke care and stroke case-fatality across Canada.

Methods:

We used the Canadian Institute of Health Information's Discharge Abstract Database to retrospectively identify a cohort of stroke/TIA patients admitted to all acute care hospitals, excluding the province of Quebec, in 11 fiscal years from 2003/2004 to 2013/2014. We used a modified Poisson regression model to compute the adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) of 30-day in-hospital mortality across time for provinces with stroke systems compared to those without, controlling for age, sex, stroke type, comorbidities, and discharge year. We conducted surveys of stroke care resources in Canadian hospitals in 2009 and 2013, and compared resources in provinces with integrated systems to those without.

Results:

A total of 319,972 patients were hospitalized for stroke/TIA. The crude 30-day mortality rate decreased from 15.8% in 2003/2004 to 12.7% in 2012/2013 in provinces with stroke systems, while remaining 14.5% in provinces without such systems. Starting with the fiscal year 2009/2010, there was a clear reduction in relative mortality in provinces with stroke systems vs those without, sustained at aIRR of 0.85 (95% confidence interval 0.79–0.92) in the 2011/2012, 2012/2013, and 2013/2014 fiscal years. The surveys indicated that facilities in provinces with such systems were more likely to care for patients on a stroke unit, and have timely access to a stroke prevention clinic and telestroke services.

Conclusion:

In this retrospective study, the implementation of integrated systems of stroke care was associated with a population-wide reduction in mortality after stroke.

Stroke systems of care are a means of coordinating and optimizing the entire stroke care continuum, from primary prevention to rehabilitation.1 They include the designation of comprehensive stroke centers,2 development of regional strategies to guarantee appropriate interventions like thrombolysis and stroke unit care, as well as interprovider collaboration with telemedicine and identification of performance measures.3

The Canadian health system is a collection of similar systems organized and funded by province or territory, resulting in regional variability in available services.4 Ontario was the first province to fully implement an integrated system of stroke care, by 2005. Its impetus included an economic analysis projecting substantial savings with an integrated approach.5 Modeled on this provincial effort, the Canadian Stroke Strategy was launched in 2005 to mobilize stakeholders in every province to invest in an integrated approach for stroke care.6 National-level working groups developed tools adaptable for use across Canada, including the Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations, training programs, quality monitoring, and public awareness campaigns.1 The funding and evolution of stroke systems varied by province and today, 6 of 13 provinces/territories have integrated stroke systems in place.

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) recently noted the paucity of data to support the contribution of stroke care systems to decline in stroke mortality.7 The differential evolution of stroke systems by province permitted a natural experiment in effectiveness of care in Canada. To inform resource investment into the wider implementation of integrated stroke systems, we investigated differences in stroke mortality between provinces with such systems and those without.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis using the Discharge Abstract Database maintained by the Canadian Institute of Health Information, which contains administrative, demographic, and limited clinical information on hospital discharges, including deaths.8 We identified a cohort of patients with stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) or TIA admitted to any acute care hospital in Canada, excluding the province of Quebec because complete data were not available, over the course of 11 fiscal years from 2003/2004 to 2012/2013. Demographic information including age, sex, stroke type (ischemic, hemorrhagic, or TIA), comorbid conditions, and year of discharge was collected from the database. The following ICD-10 codes were used to identify strokes and their subtypes: I63 (excluding I636) and H341 for ischemic strokes, I64 for stroke not specified (likely ischemic), I60 (excluding I608) for subarachnoid hemorrhage, I61 for intracerebral hemorrhage, and G45 (excluding G454) for TIA. Comorbid conditions were summarized using the Charlson-Deyo comorbidity index scale.9 Admissions that took place less than 24 hours after a patient's last discharge were considered to be part of the same episode of care. The primary outcome was 30-day in-hospital mortality. The outcome of death is well-documented in Canadian administrative data, and stroke coding in these data has been shown to have excellent specificity and sensitivity.10

In 2009 and 2013, we conducted surveys to compare resources and processes for stroke care in hospitals across Canada. In 2009, 306 hospitals participated; this rose to 601 out of 628 adult hospitals in Canada (95.7% response rate) in 2013, with a 100% response rate from 8 provinces (18 hospitals missing from Quebec and 9 from one region of Alberta). A total of 226 hospitals (excluding Quebec) participated in both surveys. The respondents at each facility were asked about key aspects of acute stroke care delivery in their institution, including the provision of care on a stroke unit, the availability of CT or MRI and carotid Doppler imaging for stroke patients, and access to neurosurgical services, stroke rehabilitation services, stroke prevention clinics, and telestroke services. Respondents were program leads who completed the survey with support from health administrators, in consultation with health care practitioners involved in direct care. Survey responses were validated with follow-up queries and telephone discussions.

A province was classified as having an integrated stroke system if there was a self-declared statement to that effect on an official Web site, a provincial committee formed for that purpose, and a clear provincial commitment of funding. Provinces with stroke systems of care were identified by the Canadian Stroke Strategy steering committee. Based on these criteria, the provinces with stroke care systems were British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island.11 The development of the provincial stroke systems was guided by the Canadian Stroke Strategy's advocacy for stroke care across the continuum of prevention, acute care, and rehabilitation as per best-practice guidelines.1 These efforts began in 2005 and took effect over the next 1–7 years. Given the centralized structure of provincial health care in Canada, some hospitals were designated as stroke centers and some were not. Prehospital transport of stroke patients to these hospitals occurred preferentially.

Summary statistics were used to describe all demographic patient information and stroke resource information gathered from the hospital surveys. Unadjusted incidence rate ratios for 30-day in-hospital mortality were calculated for each of the 11 fiscal years, for provinces with and without stroke systems. We used SAS software to construct a multivariable generalized linear Poisson regression model for 30-day in-hospital mortality including the following predictors: the presence or absence of a stroke system (yes/no), the fiscal years of discharge (as a categorical variable), as well as the common prognostic variables of age, sex, stroke type, and comorbid conditions (hypertension, atrial fibrillation, prior stroke/TIA, Charlson-Deyo index 0–1 vs 2+). As there was a significant interaction effect between the variables of stroke system of care (yes/no) and the fiscal year (type 3 analysis p < 0.0001) after adjusting for the common prognostic variables, we included an interaction term of stroke system of care and year of discharge in this model. We then presented an adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) for each single fiscal year, estimated from the model, for provinces with stroke systems of care vs those without such systems in order to graphically display the interaction effect. All tests were 2-sided and conventional levels of statistical significance (p < 0.05) were used.

RESULTS

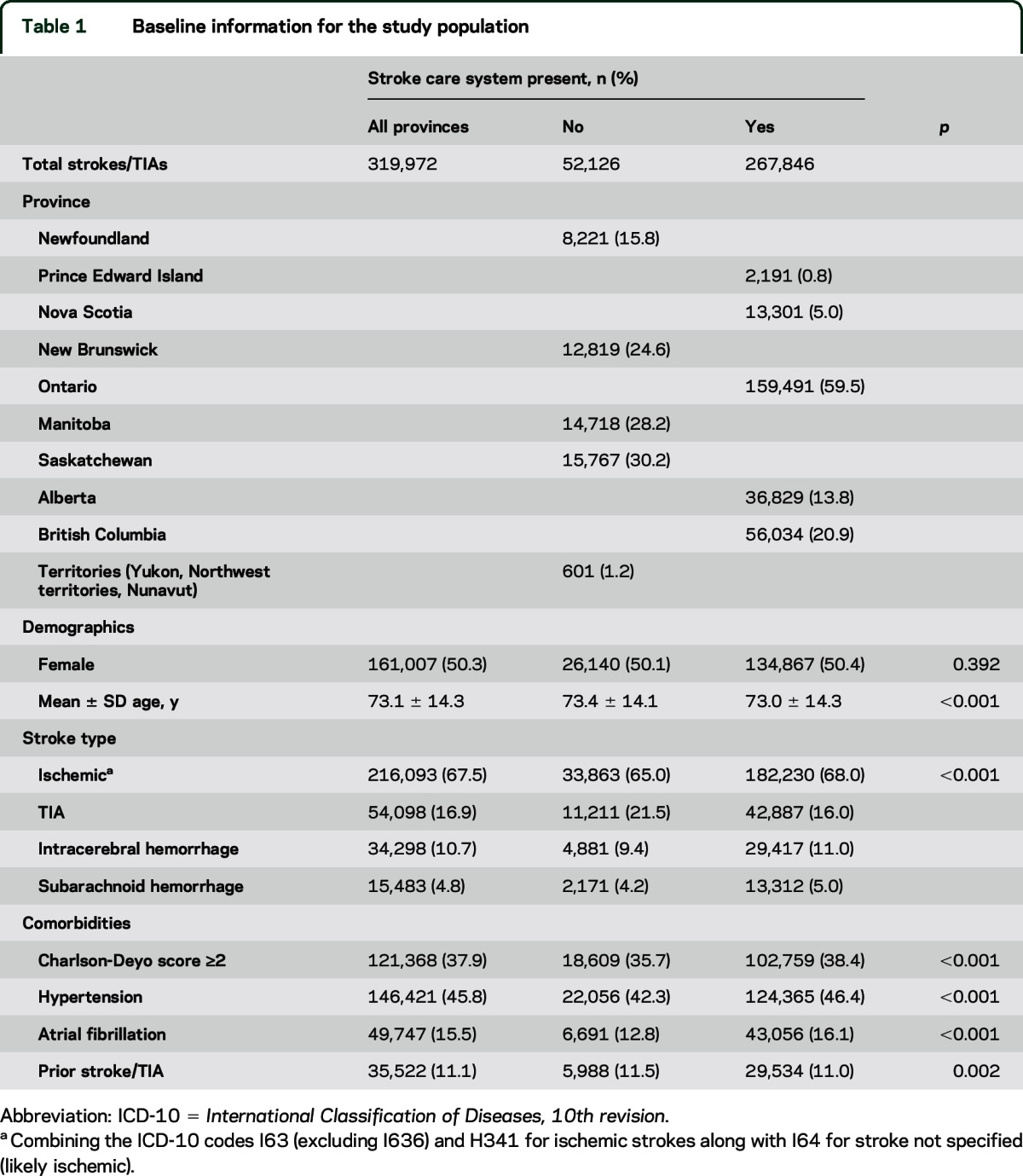

There were 319,972 patients hospitalized for stroke/TIA during the 11 fiscal years examined (table 1). The vast majority of strokes, including stroke deaths, occurred in hospitals in provinces with stroke care systems. Stroke patients in these provinces had more comorbid illness, with a greater proportion having a Charlson-Deyo score of 2 or higher, or a history of hypertension and atrial fibrillation.

Table 1.

Baseline information for the study population

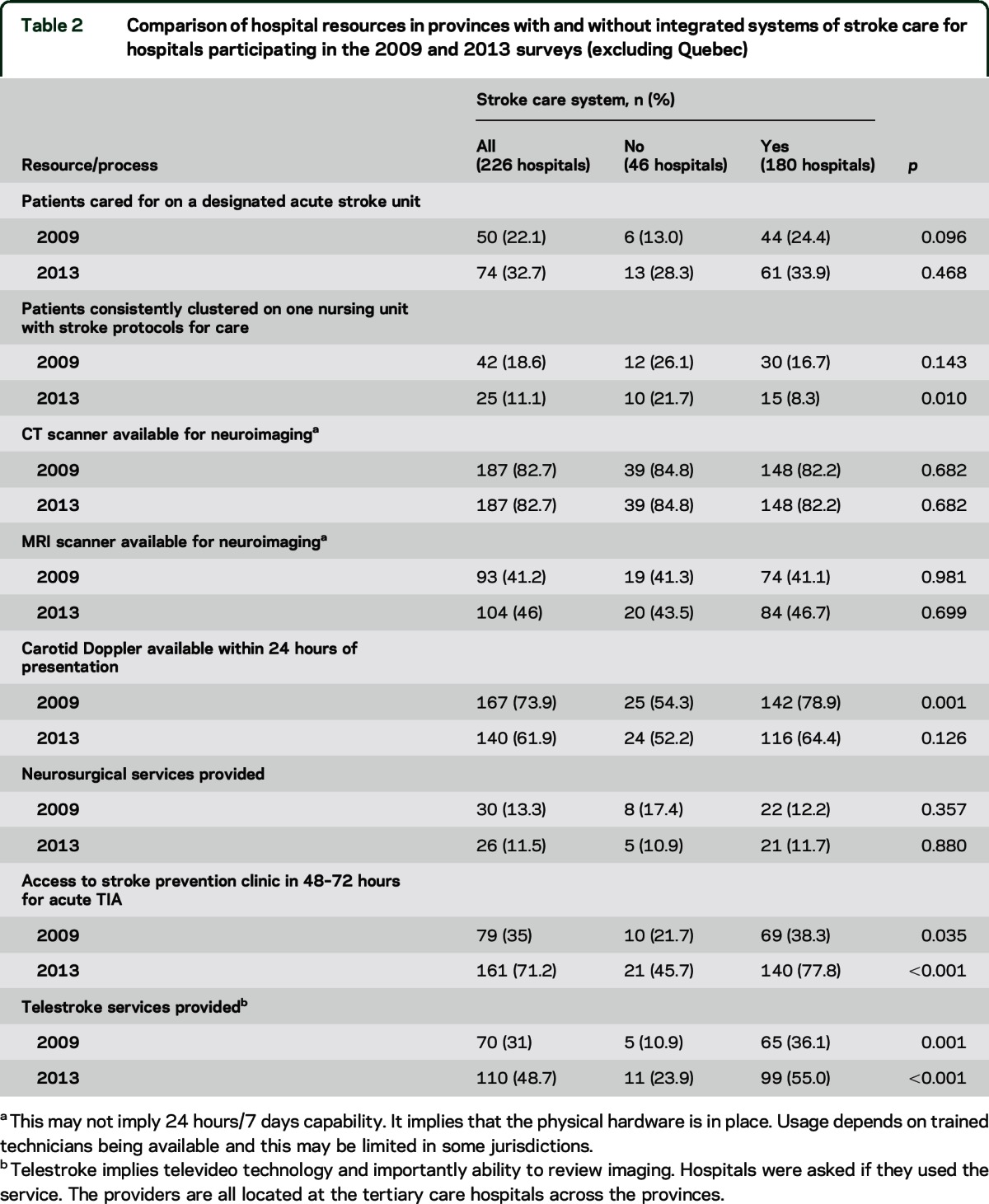

Table 2 shows the breakdown of selected hospital resources and processes of stroke care delivery in provinces with and without stroke systems of care for the 226 hospitals across Canada (excluding Quebec) that participated in our surveys in both 2009 and 2013. Hospitals in provinces with integrated systems of stroke care were more likely to report caring for stroke patients on a dedicated stroke unit—a geographically defined unit with an interdisciplinary team of health care providers and coordinated stroke services—as compared to caring for them as an intentionally grouped cluster of patients. The latter appeared to be the most commonly reported arrangement for hospitals in provinces without integrated stroke systems, in the absence of a dedicated stroke unit.

Table 2.

Comparison of hospital resources in provinces with and without integrated systems of stroke care for hospitals participating in the 2009 and 2013 surveys (excluding Quebec)

Hospitals in provinces with stroke care systems were more likely to have carotid Doppler ultrasonography available within 24 hours of presentation with stroke or TIA, though this difference diminished by 2013 due to decreased availability in both types of hospitals. These hospitals were far more likely to provide access to stroke prevention clinics within 48–72 hours for patients with acute TIA and to provide telestroke services.

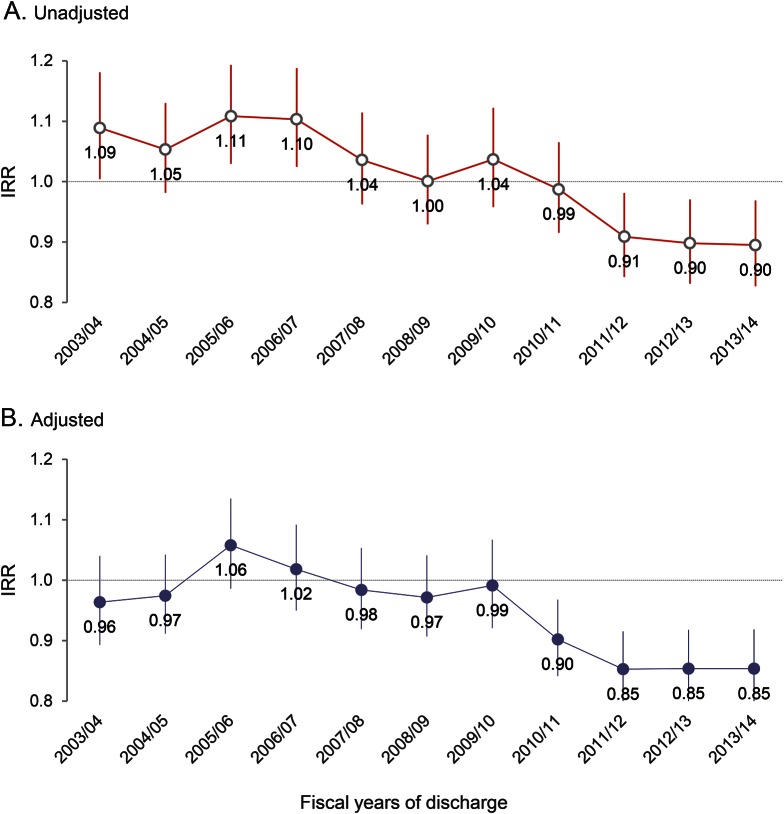

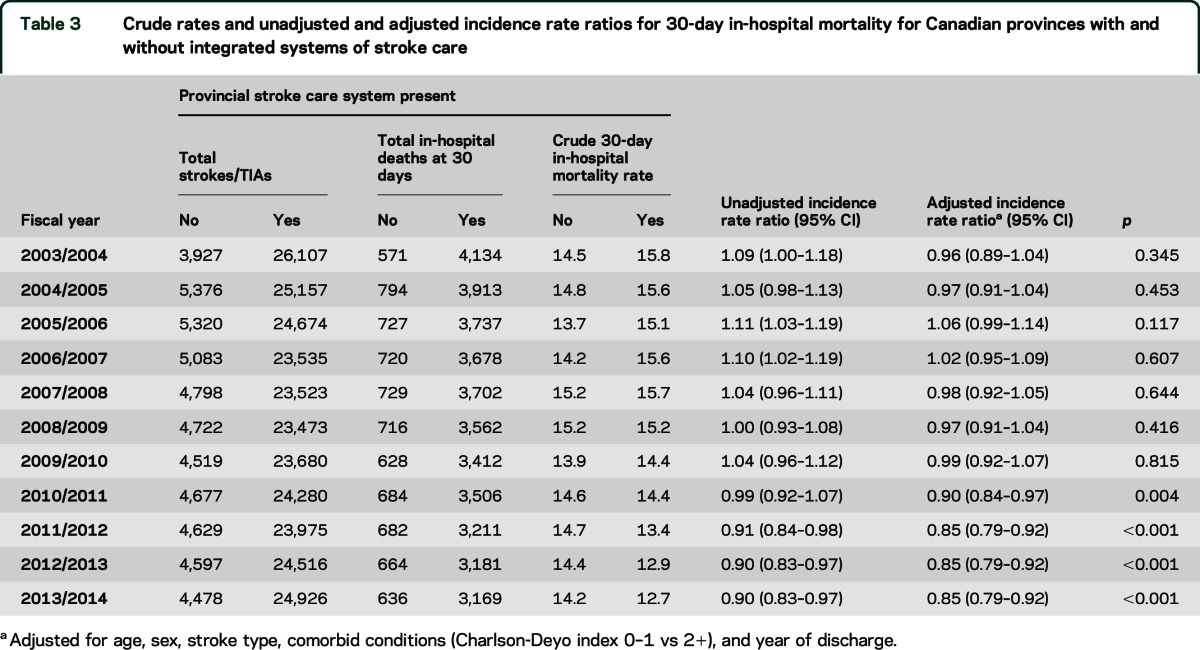

Table 3 presents the unadjusted and adjusted 30-day in-hospital mortality rates for provinces with and without stroke systems of care, represented graphically in the figure. The overall crude 30-day mortality rate decreased from 15.8% in 2003/2004 to 12.7% in 2013/2014 in the provinces with stroke care systems, while remaining constant at 14.5% in the provinces without such systems. The relative mortality rate (aIRR) was 0.85 (95% confidence interval 0.79–0.92) in 2013/2014 in provinces with stroke care systems vs those without such systems. Prior to fiscal year 2010/2011, there had been no clear difference in stroke mortality between provinces with or without stroke care systems.

Table 3.

Crude rates and unadjusted and adjusted incidence rate ratios for 30-day in-hospital mortality for Canadian provinces with and without integrated systems of stroke care

Figure. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of 30-day in-hospital mortality for provinces with and without integrated stroke systems.

(A) Unadjusted and (B) adjusted IRRs of 30-day in-hospital mortality for provinces with integrated systems of stroke care vs those without such systems.

DISCUSSION

The organization of stroke systems of care is a population-level intervention, and a recent AHA/ASA policy statement estimated that the attainment of a 2%–3% reduction in annual stroke mortality by such a system would translate into 20,000 fewer deaths in the United States and roughly 400,000 fewer deaths worldwide.12 We found a sustained decrease in 30-day in-hospital mortality over time in Canadian provinces with integrated systems of stroke care, which was not observed in those without such systems. We also found that the establishment of stroke systems was associated with an increased availability of resources including stroke units, stroke prevention clinics, and telestroke services. In addition to the known validity of stroke coding from Canadian sources, the unbiased outcome of death is also well-collected in Canadian administrative data. Thus, these data demonstrate an association between the establishment of integrated systems of stroke care nationally and population-wide reduction in acute stroke mortality.

Our results are consistent with those of a recent Canadian publication13 demonstrating that implementation of the Ontario Stroke System was associated with improved processes of care, as well as with decreases in 30-day mortality and in the proportion of patients discharged to long-term care facilities after stroke. Whereas that study used piecewise regression analyses to distinguish the effect of the provincial stroke system from underlying temporal trends in care and outcomes, our national-level analyses have the added advantages of a larger sample pool and a comparison cohort from provinces without stroke systems. Our findings are most generalizable to the Canadian health care system. Our general observation of decreased mortality in association with a multifactorial stroke system intervention—beyond just in-hospital acute care—may help inform policy decisions in other health care jurisdictions. However, it is a matter of speculation as to whether or not the components of stroke systems advocated for in other jurisdictions could result in similar mortality reductions.

The acute care interventions that have been proven with randomized controlled trials to reduce acute stroke mortality are stroke unit care,14 hemicraniectomy for malignant middle cerebral artery infarctions,15 and most recently, endovascular stroke treatment for ischemic stroke due to proximal intracranial occlusions.16 Of these, stroke unit care has the largest effect on a population basis.17 It is plausible that the sustained temporal trends in our data are reflective of a causal role for the integration of stroke care systems in the observed mortality reduction, but further evaluation is needed to justify a statement of causation. What distinguishing features of the integrated stroke systems could have actually accounted for the difference seen among the provinces? The hospital surveys indicated several potential features, including a greater likelihood of stroke patients being cared for on dedicated stroke units as compared to just intentional clusters, greater access to stroke prevention clinics within 48–72 hours for acute TIA, and greater access to telestroke services. Other components of stroke care not measured in this study, including increased use of thrombolysis and early rehabilitation services, are more available at hospitals within provinces with stroke systems of care and may have contributed to better outcomes.18

Organized stroke unit care provided by specialized multidisciplinary teams on a discrete ward dedicated to stroke patients has been found to have a robust, demonstrably stable effect in reducing stroke mortality, when compared to alternative forms of care delivery.14,19 Rapid referral to stroke prevention clinics after acute TIAs offers the opportunity to prevent a more disabling or fatal stroke and to optimize the cardiovascular risk profile. A recent retrospective cohort study found a 26% reduction in 1-year mortality rates in TIA/stroke patients referred to stroke prevention clinics compared to those not referred, even after adjustment for demographic factors, comorbidities, stroke severity measures, and other aspects of acute stroke care such as thrombolysis and stroke unit care.20 Telestroke systems have been shown to be effective in facilitating higher rates of IV thrombolysis, shortening door-to-needle times, and improving stroke outcomes, even when implemented between geographically close hospitals. A systematic review of 18 telestroke studies found that such services can lead to better functional health outcomes including reduced mortality, compared with conventional care.21 Other interventions, such as hemicraniectomy and thrombolysis (medical and endovascular), apply to a smaller proportion of stroke patients.

Some study limitations merit comment. The intervention of a stroke system of care is necessarily broad and there was wide variation in adoption and the speed of adoption in the different provinces. Stroke systems of care in each province were phased in over several years and not necessarily in parallel trajectories; for example, the Alberta Provincial Stroke Strategy was implemented in 4 phases from April 2004 to September 2007, whereas the Ontario Stroke System began emerging in 2000 and was fully implemented in 2005, culminating in the creation of the Ontario Stroke Network in 2008.22 Therefore, while we grouped all provinces with stroke systems of care together in our analysis, they were likely not all at a comparable phase of implementation until 2008. This, in addition to the natural lag expected between the implementation of such systemic changes and a measureable change in outcome data, may explain the emergence of a clear and sustained difference in mortality incidence after only the 2009/2010 fiscal year. The potential misclassification of relatively late-adopter provinces for the early part of the study period may have lowered the observed effect size.

In addition, we could not account for the potential effects of concurrent interventions, such as stroke specialist training programs and variability in adherence to national best practices recommendations. We did not adjust for stroke severity in our study and could not ascertain the different causes of mortality, because this information was not available in our administrative dataset. Other factors such as improvements in primary care or secondary prevention measures may have modulated the stroke severity and consequently the stroke-related mortality in patients in the stroke system group. Patients in that group were also more likely to have identified comorbidities like atrial fibrillation, and the appropriate management of these may have contributed to lower mortality. Given that the vast majority of strokes in our study occurred in the provinces with stroke care systems, it is possible that a volume/practice effect could have played a role in improving the mortality rates. Nevertheless, such an effect would still have occurred within the environment of an integrated stroke system, and it would be difficult to dissociate these likely complementary influences.

Furthermore, the outcome of 30-day mortality in our study may not reflect other clinical outcomes of interest, like 90-day or longer-term mortality or functional outcome measures. We are unable to comment on the cost-effectiveness of the stroke systems or their influence on stroke incidence. Many facets of stroke systems, like stroke units, were not represented in high percentages even in the stroke system group and the utilization of many other relevant interventions—such as thrombolysis, endovascular treatment, treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage, hemicraniectomy, or hospice care—was not evaluated. Finally, the quality and consistency of the results of the surveys, particularly in comparing the 2009 and 2013 results, may have been limited by variability in the interpretation of questions by the respondents.

The Canadian experience suggests that the establishment of regional/provincial integrated systems of stroke care has resulted in a demonstrable difference in stroke mortality at a population level. Further reduction in mortality may be expected as stroke systems of care continue to become established across all provinces in Canada and elsewhere internationally.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- AHA/ASA

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association

- aIRR

adjusted incidence rate ratio

- ICD-10

International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision

Footnotes

Editorial, page 886

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.G. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. P.L. managed the data linkage and survey. J.F. conducted statistical analysis. P.L. and M.D.H. led the evaluation strategy for the Canadian Stroke Strategy. M.K.K., R.C., and I.J. contributed to data analysis and writing. A.M.H. led the Canadian Stroke Network and conceived of the Canadian Stroke Strategy. M.D.H. was the senior author. All authors reviewed the final manuscript and made significant contributions to analysis and writing.

STUDY FUNDING

Funding for the Canadian Stroke Strategy and this analysis were provided by the Canadian Stroke Network and the Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada. The sponsors are a public and health charity, respectively, and did not design the study or analyze or interpret the results. The authors take full responsibility for the analysis and interpretation.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindsay P, Bayley M, McDonald A, Graham I, Warner G, Phillips S. Toward a more effective approach to stroke: Canadian Best Practice Recommendations for Stroke Care. Can Med Assoc J 2008;178:1418–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberts M, Latchaw R, Selman W, et al. Recommendations for comprehensive stroke centers: a consensus statement from the Brain Attack Coalition. Stroke 2005;36:1597–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwamm L, Pancioli A, Acker JR, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of stroke systems of care: recommendations from the American Stroke Association's Task Force on the Development of Stroke Systems. Stroke 2005;36:690–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis S. A system in name only: access, variation, and reform in Canada's provinces. N Engl Journal Med 2015;372:497–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamdani M, Tu J. Appendix 5: Emergency/Acute Stroke Task Group Economic Decision Analysis Model. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindsay P, Cote R, Hill M, et al. 1.3 Canadian Stroke Strategy. The Quality of Stroke Care in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Stroke Network; 2011:7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lackland DT, Roccella EJ, Deutsch AF, et al. Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:315–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) Metadata [online]. Available at: http://www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/internet/en/document/types+of+care/hospital+care/acute+care/dad_metadata. Accessed July 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokotailo RA, Hill MD. Coding of stroke and stroke risk factors using International Classification of Diseases, revisions 9 and 10. Stroke 2005;36:1776–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsay P, Cote R, Hill M, et al. Appendix A: Provincial Information: The Quality of Stroke Care in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Stroke Network; 2011:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higashida R, Alberts MJ, Alexander DN, et al. Interactions within stroke systems of care: a policy statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013;44:2961–2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapral M, Fang J, Silver F, et al. Effect of a provincial system of stroke care delivery on stroke care and outcomes. Can Med Assoc J 2013;185:E483–E491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collaboration SUT. Organized inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vahedi K, Hofmeijer J, Juettler E, et al. Early decompressive surgery in malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery: a pooled analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langhorne P, Lewsey JD, Jhund PS, et al. Estimating the impact of stroke unit care in a whole population: an epidemiological study using routine data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010;81:1301–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganesh A, Camden M, Lindsay P, et al. The quality of treatment of hyperacute ischemic stroke in Canada: a retrospective chart audit. CMAJ Open 2014;2:E233–E239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Candelise L, Gattinoni M, Bersano A, et al. Stroke-unit care for acute stroke patients: an observational follow-up study. Lancet 2007;369:299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webster F, Saposnik G, Kapral M, Fang J, O'Callaghan C, Hachinski V. Organized outpatient care: stroke prevention clinic referrals are associated with reduced mortality after transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke. Stroke 2011;42:3176–3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson T, Wild C. Telemedicine in acute stroke management: systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2010;26:149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberta Provincial Stroke Strategy Project Process [online]. Available at: http://www.strokestrategyab.ca/PDFs/APSS_Development_Process.pdf. Accessed July 2, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.