Abstract

Wild soybean, the direct progenitor of cultivated soybean, inhabits a wide distribution range across the mainland of East Asia and the Japanese archipelago. A multidisciplinary approach combining analyses of population genetics based on 20 nuclear microsatellites and one plastid locus were applied to reveal the genetic variation of wild soybean, and the contributions of geographical, environmental factors and historic climatic change on its patterns of genetic differentiation. High genetic diversity and significant genetic differentiation were revealed in wild soybean. Wild soybean was inferred to be limited to southern and central China during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and experienced large-scale post-LGM range expansion into northern East Asia. A substantial northward range shift has been predicted to occur by the 2080s. A stronger effect of isolation by environment (IBE) versus isolation by geographical distance (IBD) was found for genetic differentiation in wild soybean, which suggested that environmental factors were responsible for the adaptive eco-geographical differentiation. This study indicated that IBE and historical climatic change together shaped patterns of genetic variation and differentiation of wild soybean. Different conservation measures should be implemented on different populations according to their adaptive potential to future changes in climate and human-induced environmental changes.

Genetic diversity is key for a species to survive and adapt to changing environments1, and one fundamental task in biology is to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the origin and maintenance of genetic variation2. The detailed information of genetic variation could be applied to reveal the demographic history and population structure of a species3,4,5 and the underlying genetic mechanisms of local adaptation and evolutionary changes6,7,8,9,10.

Two processes are widely acknowledged to be major drivers of genetic differentiation: isolation by geographical distance (IBD) and isolation by environment (IBE)11,12,13,14. Under the IBD scenario, the amount of gene flow is mainly restricted by geographical distance, and genetic differentiation is expected to increase according to the distance between populations15. However, under IBE, the fitness of immigrants or hybrids between adjacent populations that adapt to distinct environments may be reduced by natural selection12, which will facilitate or maintain genetic divergence16, and the genetic differentiation between populations is correlated to the influence of environmental variables on gene flow11,17. Geographical processes may influence the genetic structure of a population at large spatial scales, whereas ecological processes may influence the genetic structure of a population at small spatial scales18,19. In addition to the above contemporary geographic and environmental factors, shifting environmental conditions over time may be crucial factors for genetic differentiation20. Recent studies have considered the relative contribution of IBD and IBE on genetic variation at a species-wide scale15,21,22,23,24,25. However, few studies have jointly considered the relative importance of the contemporary IBD and IBE and historical climate change on genetic variation.

East Asia exhibits high topographic complexity and climate variability and harbours high levels of diversity of temperate plant species26. Although this region has never been directly impacted by extensive and unified ice-sheets27, it experienced severe climatic oscillations throughout the Quaternary, with dramatic effects on the evolution and distribution of both plants and animals28. The Japanese Archipelago was repeatedly connected with East China via the exposed wide stretches of continental shelf of the East China Sea (ECS) during glacial periods29. Simulated paleovegetation reconstructions suggest that a band of warm temperate deciduous forest extending on this land-bridge across the ECS connected the presently isolated temperate forests of China and Japan during the Last Glacial Maximum28. As one of the earliest and most human-influenced regions, the local biological diversity has been significantly affected by overexploitation and intensive agriculture and land use practice. Wild soybean is the direct progenitor of cultivated soybean (Glycine max (Linnaeus) Merrill), which is widely distributed in East Asia, including major parts of China, the Japanese archipelago, the Korean peninsula and the Russian Far East30. Wild soybean usually grows in moist habitats near freshwater resources from the sea to 2650 m above sea level, in subtropical (southward to 24°N) to subfrigid zones (northward to 53°N). It also occurs in various habitats in salty lands and seasonally dry areas. Wild soybean is mainly distributed in open habitats with frequent human activities, and its distribution region has been significantly fragmented and reduced by land exploitation and utilization. This species is even extinct in the wild in some regions and has been listed as a rare and endangered plant in China31. Wild soybean thus supplies a good model to address the relative contribution of IBD, IBE and historical climatic change on its genetic variation and to explore conservation measures that integrate present genetic variation and changes in distribution under historical climatic change.

Various molecular markers, such as RAPD, SSRs and gene sequences, have been applied to address the population structure of wild soybean31,32,33,34,35. High intra- and inter-population genetic variation has been revealed34,36,37,38,39. Three evolutionary significant units (ESUs) were revealed by some studies: Northeast, Southeast and Yellow River Valley40,41, whereas other recent studies tend to combine the Northeast and Southeast into one ESU31,39. Some recent studies found a correlation between genetic distance and geographical distance33,42, which indicates IBD is involved in the genetic differentiation of wild soybean. However, the influence of environmental variables on the genetic divergence (namely IBE) of this species has not been addressed.

Applying 20 nuclear Simple Sequence Repeat markers (nSSRs) and one cpDNA locus (trnQ-rps16) and a multidisciplinary approach combining population genetic analyses, ecological niche modelling, a Bayesian skyline plot, a Mantel test and a principle components analysis, the major aims of this study were (i) to detect the genetic variation of wild soybean; (ii) to elucidate the relative contribution of geographical, environmental and historical effects on the distribution and genetic differentiation of wild soybean; and (iii) to predict the fate of wild soybean as it is confronted with rapid environmental and climate changes and to provide information to design effective conservation and management strategies for wild soybean.

Results

Genetic variation and structure of wildsoybean

For microsatellite data from 43 populations, a null homozygote was found in all the loci with low frequencies (<5%). All 20 loci were polymorphic (Table S1). The polymorphism information content (PIC) for each locus ranges from 0.764 to 0.940, with an average of 0.883 (Table S1). Genetic diversity parameters are presented in Table 1. Alleles in wild soybean are rich, with an average of 3.3 alleles per population. The mean expected heterozygosity (HE) is 0.426 over all loci for each population ranging from 0.018 to 0.797. High differentiation was revealed by the global FST value (0.509), which indicated significant population genetic structure existed in wild soybean populations. The AMOVA analysis of nSSRs revealed that 6.0% of the genetic variation was due to the genetic distance between the two clusters, 46.7% was due to populations within clusters and 47.3% was due to individuals within populations (Table 2).

Table 1. Genetic diversity parameters estimated by 20 nSSRs in 43 populations of wild soybean.

| Pop. | A | HO | HE | PIC | Pop. | A | HO | HE | PIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF | 3.2 | 0.014 | 0.397 | 0.359 | JZ | 2.2 | 0.018 | 0.455 | 0.357 |

| HY | 4.4 | 0.014 | 0.605 | 0.562 | QH | 2.5 | 0.010 | 0.212 | 0.195 |

| JO | 2.3 | 0.007 | 0.300 | 0.260 | WQ | 4.1 | 0.003 | 0.555 | 0.513 |

| QZ | 2.8 | 0.015 | 0.456 | 0.387 | XH | 2.4 | 0.000 | 0.367 | 0.310 |

| RY | 1.8 | 0.018 | 0.094 | 0.088 | YT | 1.2 | 0.005 | 0.037 | 0.030 |

| DQ | 2.9 | 0.051 | 0.468 | 0.407 | HL | 5.1 | 0.037 | 0.658 | 0.614 |

| SC | 5.7 | 0.023 | 0.722 | 0.687 | JH | 5.4 | 0.082 | 0.694 | 0.649 |

| TB | 6.8 | 0.007 | 0.797 | 0.769 | KS | 3.1 | 0.003 | 0.582 | 0.513 |

| WC | 6.2 | 0.053 | 0.762 | 0.729 | LX | 3.4 | 0.028 | 0.520 | 0.468 |

| XU | 5.7 | 0.205 | 0.708 | 0.665 | 3.9 | 0.003 | 0.504 | 0.460 | |

| CK | 2.9 | 0.037 | 0.491 | 0.427 | SY | 1.3 | 0.061 | 0.076 | 0.061 |

| CY | 1.9 | 0.013 | 0.200 | 0.173 | J1 | 3.2 | 0.021 | 0.563 | 0.506 |

| GH | 3.1 | 0.048 | 0.426 | 0.379 | J2 | 1.2 | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.017 |

| N1 | 3.0 | 0.027 | 0.383 | 0.342 | J3 | 1.2 | 0.003 | 0.064 | 0.053 |

| N2 | 2.6 | 0.067 | 0.407 | 0.332 | J4 | 3.2 | 0.034 | 0.467 | 0.048 |

| YJ | 2.6 | 0.014 | 0.414 | 0.341 | J5 | 2.9 | 0.069 | 0.45 | 0.393 |

| BX | 4.9 | 0.028 | 0.570 | 0.533 | K1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.082 |

| HX | 4.9 | 0.071 | 0.598 | 0.560 | K2 | 1.3 | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.022 |

| LW | 2.0 | 0.007 | 0.265 | 0.225 | K3 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.153 | 0.133 |

| WS | 3.8 | 0.017 | 0.520 | 0.473 | K4 | 6.3 | 0.092 | 0.708 | 0.673 |

| YL | 2.4 | 0.010 | 0.302 | 0.260 | K5 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 0.711 | 0.660 |

| DY | 3.4 | 0.018 | 0.526 | 0.470 | mean | 3.3 | 0.031 | 0.426 | 0.373 |

A: number of alleles; AR: allele richness; HO: observed heterozygosity; HE: expected heterozygosity; PIC: polymorphism information content.

Table 2. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) for wild soybean.

| Loci | Source of variation | SS | VC | PV(%) | Fixation indices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nSSR | Among two lineage | 393.04 | 0.565 | 5.99 | FCT = 0.006 |

| Among populations within lineage | 5106.23 | 4.409 | 46.69 | FST = 0.527 | |

| Within populations | 5050.64 | 4.469 | 47.32 | FSC = 0.497 |

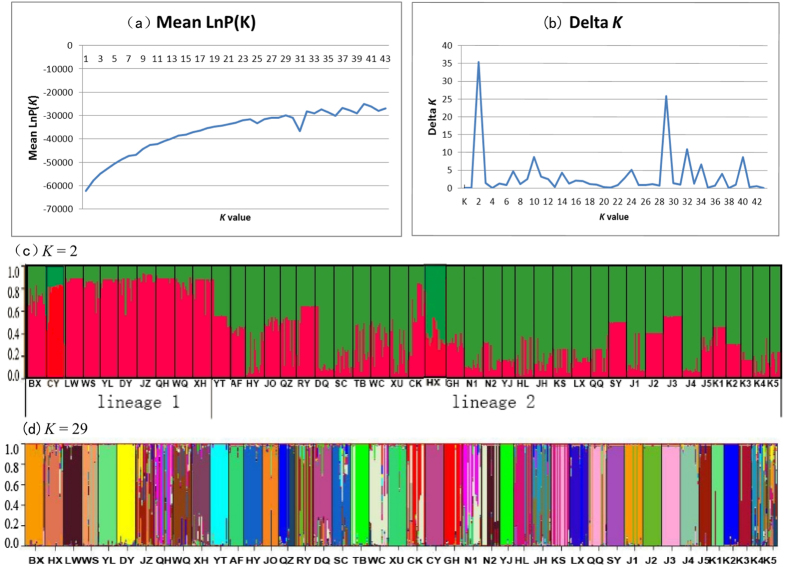

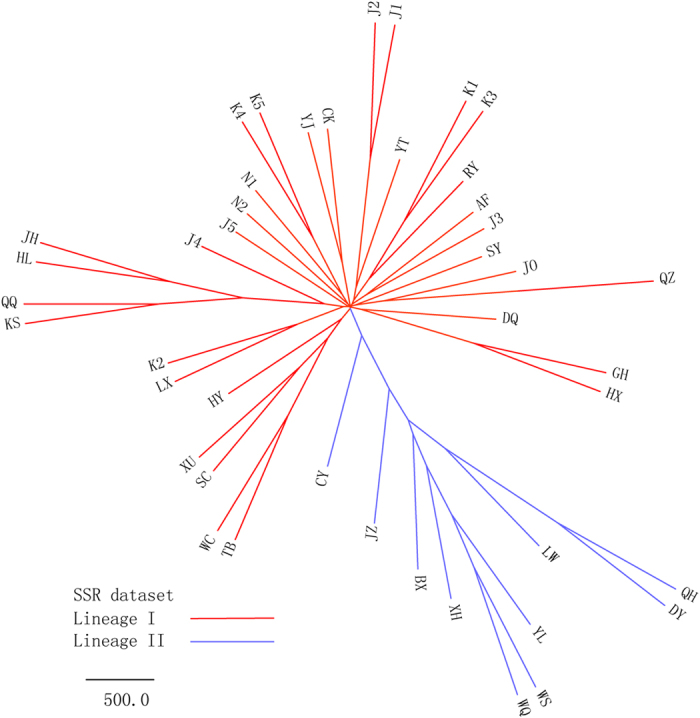

The UPGMA tree based on Nei’s standard genetic distance is shown in Fig. 1. The 43 wild soybean populations were resolved into two lineages: lineage I was formed by eight populations from the Yellow River and Huai River valley in addition to population CY from Tibet; lineage II was formed by the remaining 34 populations. Populations from Japan and Korea did not form independent lineages. The MCMC structure reconstruction of nSSRs is shown in Fig. 2. ΔK showed extremely high values at K = 2 and 29 when Evanno’s ad hoc estimator of the actual number of groups was used (Fig. 2b). When K = 2, two clusters were separated that largely correspond to those of the UPGMA analyses (Fig. 2c). Figure 2d showed the inferred clusters with K = 29 and revealed uniform and admixed populations. For example, a comparison of the K5 and J2 populations showed a low level of genetic similarity within the site in the former population, indicating population admixture, whereas the latter population was very uniform and showed only minor differences between microsites.

Figure 1. Clustering analysis of wild soybean populations based on UPGMA.

Figure 2. Inferred population structure based on 43 populations and 20 nSSRs of wild soybean.

(a) Genetic structure of wild soybean inferred from the admixture model (K = 2); (b) Genetic structure of wild soybean inferred from the admixture model (K = 29).

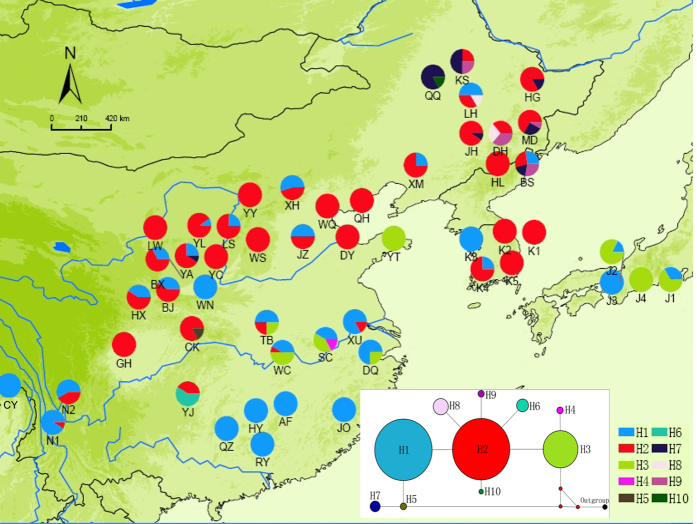

A total of 10 different cpDNA haplotypes (H1–H10) were identified based on 9 polymorphism sites detected from trnQ-rps16. Different haplotypes had quite different frequencies: H1 (35.2%) and H2 (46.1%) were two most common and widespread haplotypes, which were found in most populations of wild soybean. However, each of H5, H6, H7 and H10 was an endemic haplotype, which was found in only one population (Fig. 3). The ancestral haplotype could not be identified.

Figure 3. Haplotype distributions of wild soybean populations.

(ArcMap v9.3 and NETWORK v4.6: http://www.fluxus-engineering.com/sharepub.htm#a10).

The Bayesian Skyline plots indicated that the population size of wild soybean has experienced a rapid increase following a long period of relative stability. This rapid increase was inferred to occur after the last glacial maximum and at the beginning of the warming period in the early Holocene (15,000 years before present, Fig. S1).

Relationships between genetic variation and environmental versus geographical factors

A Mantel test revealed a significant correlation between genetic distance and environmental distance (r = 0.233, P = 0.002), but no significant correlation exists between genetic distance and geographical distance (r = −0.016, P = 0.341). When geographical factors were controlled, a partial Mantel test also revealed isolation by environmental distance (r = 0.232, P = 0.001). Where as when environmental factors were controlled, we could not detect significant correlations between genetic differentiation and geographical distance (r = −0.002, P = 0.508). The MMRR analysis suggested that the environment factors had a higher regression coefficient, whereas the effects of geographic distance were not significant (geographic distance: β = 0.005677, P = 0.2939; environment distance: β = 0.205233, P = 0.0249; Table 3).

Table 3. Results of the Mantel test, partial Mantel test and MMRR analysing the correlation between geographical distances, environmental distances and Nei’s genetic distance based on microsatellite data.

| Mantel test |

partial Mantel test |

MMRR |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P value | r | P value | β | P value | |

| Gen. Geo | −0.016 | 0.341 | −0.002 | 0.508 | 0.006 | 0.294 |

| Gen. Env | 0.233 | 0.002 | 0.232 | 0.001 | 0.205 | 0.025 |

Regular letters refer to non-significant results and bold letters refer to significant correlations.

Geo, geographical distance; Gen, genetic distance; Env, environmental distance.

LGM, Present and future distribution of wild soybean

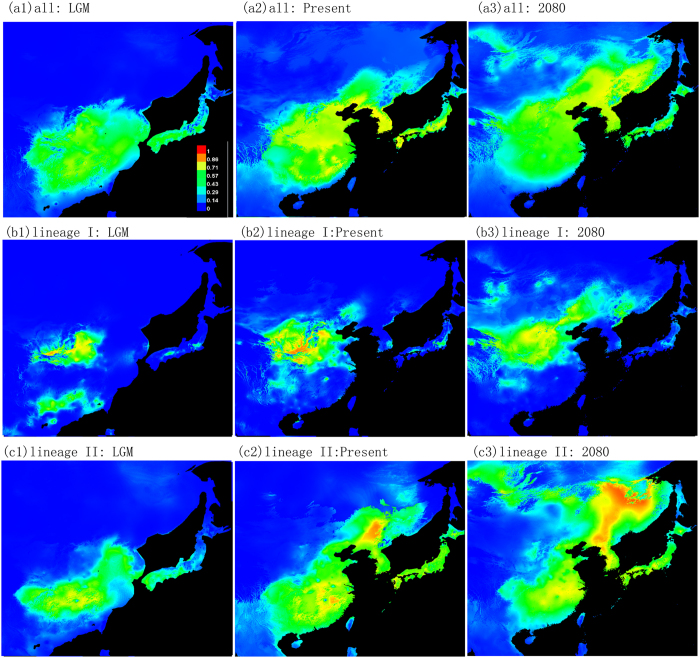

All models performed well with AUC values >0.9 (n = 10 replicate model runs) suggesting a high fit of the model43. The predicted distribution of wild soybean (Fig. 4a2) is consistent with the observed present distribution, indicating that the distribution is restricted by environmental factors. A Jackknife of the regularized training gain revealed that bio2, bio3 and bio15 made only small contributions to model development. However, bio1, bio4, bio5 and bio13 contributed the most to model development. Over all, temperature had a greater influence on wild soybean than precipitation (Fig. S2). The distribution of the LGM based on MIROC (Fig. 4a1) differed substantially from the present. The estimated distribution of wild soybean during the LGM was restricted to southern and central China. No suitable habitat found in northeastern China and northern Honshu in Japan. Both lineages I and II experienced a northward shift after the LGM; however, lineage I has expanded on a much smaller scale than lineage II. Lineage II has most probably dispersed into northern and northeastern China, Korea, and northern Japan from its southern refugia. When the models were projected to future climates in 2080, lineage I and lineage II were modelled to show a significant northeastward shift of suitable habitats to Northeast China (NEC) and the Russian Far East (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4. Potential distributions as the probability of occurrence for wild soybean.

Suitability values indicate logistic probabilities ranging from 0–1, with increasingly darker shades of red with increasing habitat suitability. (a) All populations; (b) Lineage I; (c) Lineage II (MAXENT v3.3.3 & Adobe illustrator CS2).

Discussion

The distribution and genetic variation of wild soybean have been significantly shaped by historical climate change. The SSR data resolved wild soybean into two lineages, with lineage I formed by a group of populations from the Yellow River and Huai River valley and lineage II formed by populations from other regions (Figs 1 and 2). The phylogenetic analyses of trnQ-rps16 failed to detect any deep subdivisions within wild soybean, two commonly haplotypes (H1 and H2) were widely distributed across the range of wild soybean (Fig. 3), and there was no significant geological pattern of genetic and haplotype diversification. The ecological niche modelling analyses suggested the relative narrower distribution of wild soybean during the LGM, which was restricted to central and southern China south of 40°N. There was no suitable habitat modelled in northeastern China, Korea or northern Japan during the LGM, and the present wild soybean populations in these regions probably originated from the northward range shift after the LGM. Both lineages I and II experienced a northward shift after the LGM, though lineage I has expanded on a much smaller scale than lineage II. The large-scale expansion of wild soybean after the LGM is largely consistent with the inferred rapid expansion at approximately 15000 years BP by the BSP analysis (Fig. S1). However, the genetic diversity of wild soybean was not significantly correlated with latitude in northern Eastern Asia (Fig. S3), and multiple endemic plastid haplotypes were detected in NEC, which contrasts with a scenario of a large scale post-glacial northward expansion from southern China, with reduced levels of genetic variation throughout the recolonized regions. We thus could not totally exclude the possibility of the survival of wild soybean in the micro refugia in NEC. Some studies have suggested that mountain glaciers formed only over 2000 metres in the Changbai Mountain region during the late Pleistocene44, and lower elevation zones may have had relatively a mild Pleistocene climate and supply microclimatic habitats for biological taxa during glacial periods. Multiple recent phylogeographic studies also suggested refugia in NEC45,46,47.

The geographical pattern of genetic variation of wild soybean was also inferred to be significantly affected by contemporary environmental factors. Traditionally, IBD has been considered a major driver of population divergence48. Recently, problems were detected with IBD49, and IBE has been considered as a more important driving force for genetic differentiation50,51,52. Recent studies have begun to jointly estimate the relative contribution of these two forces on genetic differentiation at a specific level15,50,53. The comprehensive meta-analysis by Shafer & Wolf54 suggested the widespread nature of ecologically induced divergent selection in nature. Some recent studies on different plant species also found that IBE plays a more important role in intraspecific genetic differentiation15,53. However, IBD was inferred to have a stronger effect than IBE on genetic structure in other plant taxa24. The interplay of IBD and IBE in the genetic divergence of species appears to be intricate and system dependent53. A stronger effect of IBE versus IBD was found for the genetic differentiation of wild soybean. A Mantel test, partial Mantel test and MMRR analysis all supported the effect of isolation by environmental distance. Multiple ecological processes could shape the pattern of isolation by environment55. Wild soybean occurs in diversified habitats across its wide distribution region, and ecological landscape heterogeneity may influence gene flow and connectivity between populations that are adapted to different environments. The PCA analysis showed that temperature and precipitation explain 79.51% of the genetic variation of wild soybean. The Jackknife analysis of ecological niche modelling revealed both precipitation and temperature made a great contribution to model development. All these results indicated that environmental factors played a major role in shaping the genetic structure of the species. Previous studies have suggested the major role of temperature and precipitation in the general adaptation of some other plants56.

Integrating the present genetic variation and the contribution of environmental factors to patterns of genetic differentiation, ecological niche modelling of the distribution of biological taxa in past, present and future climates can provide important clues for conserving wild resources. The overlaps between modelled past and present distributions may reveal areas of refugia rich in genetic diversity57,58. Instead, the lack of overlap between present and predicated future distributions may reveal populations under potential threat from climate change59. Both situations will supply clues for conserving wild resources of particular importance and breeding new cultivars adapted to future environmental changes60,61. Areas of predicted habitat loss should be special targets for ex situ conservation in seed banks, botanic gardens, or other germplasm repositories; locations where habitat is likely to be retained may be priorities for in situ conservation measures62,63. Wild soybean was inferred to have a very southern and limited modelled distribution in central and southern China during the LGM, and the modelled suitable habitat will have an obviously northeastward shift in the 2080 s. The present and previous studies have not detected higher population genetic diversification in overlap regions between modelled past and present distributions, and therefore, these areas need not be considered as priority conservation regions. The inferred significant northeastward shift of suitable habitat in the 2080 s suggests that suitable habitat will be lost in the broad region of southern China. At the same time, potential new habitats will be gained, most notably in NEC and the Russian Far East. Large scale ex situ conservation measures should be carried out for wild soybean in southern China. The mountain regions of southern China have high micro-geographic environmental heterogeneity, and wild soybean may find suitable habitat through migration over short distances. Therefore, the ex situ measures should first consider populations on plains in these regions. Wild soybean usually chooses to live in open habitat, and moderate human disturbance could be beneficial to its establishment and expansion. However, high-density agricultural practices will fragment its habitat. The NEC region is the most concentrated area of agricultural production in China, and many habitats and populations of wild soybean are rapidly diminishing. Comparing large-scale surveys between 1979 to 1983 and 2002 to 2004 revealed large range reductions of wild soybean in this region64. Some large populations have disappeared following land conversion for agriculture, which has led to the permanent loss of genotypes, such as the white-flowered soybean type31. As the most suitable region for wild soybean in the future, the conservation of wild soybean in this highly disturbed region is not optimistic and the worth of such a project would require further study. Furthermore, environmental factors were inferred to be responsible for the adaptive differentiation of wild soybean, and we should study its local adaptation to new climate conditions for efficient conservation in the face of future climate change.

Conclusions

Our analyses revealed high genetic variation and differentiation among populations of wild soybean. Wild soybean was inferred to be limited to southern and central China during the LGM, with a large-scale northeastward expansion after the LGM. A significant correlation between genetic distance and environmental distance was identified, which suggested that environmental factors were responsible for the adaptive eco-geographical differentiation of different populations. In combination with genetic studies, the ecological niche modelling of past, present and future distributions is an efficient way to predict geographic regions of high genetic diversity and geographic regions under threat due to future climate change. An urgent area of future study is the possibility for the local adaptation of wild soybean populations to new climate conditions.

Methods

Sampling

A total of 604 individuals of wild soybean were collected from 2007 to 2011 in 53 different localities across most of its distribution areas (Table S2, Fig. S4). Individuals separated by at least 50 metres were sampled randomly to avoid collecting ramets from a single genet. Fresh healthy leaves were collected from each sampled individual and dried in silica gel for subsequent DNA extraction. Total DNA was extracted from the dried leaves following the modified CTAB method described by Doyle65. The purified total DNA was quantified by gel electrophoresis, and its quality was verified by spectrophotometry. The DNA samples were stored at −20 °C.

Genotyping of microsatellite loci and cpDNA sequencing

To reduce experimental expenses, genotyping was performed for 43 representive from 53 sampled wild soybean populations using 20 nSSRs, as in previous study (Table S1, He et al.31). PCR reactions were performed in 15 μL of reaction containing 30–50 ng genomic DNA, 0.6 μM of each primer, 7.5 μL 2 × Taq PCR MasterMix (Transgen, Beijing, China). PCR amplifications were conducted under the following conditions: 94 °C for 2 min; 35 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min; followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products were separated on an ABI 3730 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). Fragment sizes were scored automatically using the program Genemapper (Applied Biosystems).

The plastid trnQ-rps16 was amplified from 599 individuals representing 52 of 53 populations (we failed to amplify this locus from population J5) using a primer pair of trnQ (GCGTGGCCAAGYGGTAAGGC) and rps16 (GTTGCTTTYTACCACATCGTTT)66. TrnQ-rps16 was amplified and sequenced following the methods of Shaw, et al.66. The PCR products were purified with an EasyPure PCR Purification Kit (TransGen). Purified PCR products were sequenced directly on an ABI 3730 sequencer.

Genetic analysis of microsatellite variation

The number of alleles (A), the observed heterozygosity (HO) and expected heterozygosity (HE) were calculated using GENEALEX v6.467. The polymorphism information content (PIC) was calculated with PowerMaker v3.2568 according to Botstein, et al.69. A hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA)70 implemented in Arlequin v. 3.1171 was used to partition the observed genetic variation among clusters, among populations within a cluster and among individuals within a population.

Genetic differentiation between populations was assessed by the calculation of pairwise FST values among sampling locations, and their significance was calculated with 10,000 permutations implemented in Arlequin v3.1171. A dendrogram based on Nei’s standard genetic distance (Dnei)72 between populations was constructed using the UPGMA method implemented in PHYLIP v3.6873. Genetic differentiation was investigated using the model-based clustering method STRUCTURE v2.174,75 for nSSRs. The burn-in time and replication number were set to 100,000 and 100,000 (further generation following the burn in) for each run, respectively. The number of populations (K) in the model was systematically varied from 1 to 43. To decrease the margin of error, an average value of 20 simulations performed for each K was used. We used the ΔK method, representing the highest median likelihood values, to assign wild soybean accessions using the online tool Structure Harvester76. For the chosen K value, the run that had the highest likelihood estimate was adopted to assign individuals to clusters. The results were visualized using DISTRUCT v1.177.

Genetic analysis of cpDNA sequence

Gaps (indels) detected in the cpDNA dataset were treated as single mutation events and coded as substitutions (A or T). The haplotype distribution map was constructed using ArcMap v9.3 (ESRI, Redlands, California, USA). A haplotype network was conducted in NETWORK v4.678 using Glycine tabacina as an outgroup. A Bayesian Skyline Plot (BSP) in Beast was employed to reconstruct demographic history79. This coalescent-based inference method uses a Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling procedure with gene sequence data to estimate a posterior distribution of effective population size through time. To infer the historical demographics of wild soybean, a nucleotide substitution rate of 1.52 × 10−9 substitutions per neutral site per year (s/s/y)80 was assumed. Markov chains were run for 2.0 × 10−7 generations and were sampled every 1,000 generations, with the first 10% being discarded as burn-in.

Correlations of genetic, geographical and environmental factors

First, the 19 climatic variables of the studied sites were extracted from the WorldClim data set (http://www.worldclim.org/) interpolated to 30-arcsec (ca. 1 km) resolution81 using ArcGIS. Then, pairwise Pearson correlations between the 19 factors were calculated. When a pair had a Pearson correlation >0.8, one of the two variables was removed82 (Table 4). Finally, seven factors (bio1 = annual mean temperature; bio2 = mean monthly temperature; bio3 = isothemality; bio4 = temperature seasonality; bio5 = max temperature of warmest month; bio13 = precipitation of wettest month; bio15 = precipitation seasonality) were chosen as representative of climate factors.

Table 4. Multi-collinearity test using cross-correlations (Pearson correlation coefficients, r) among environmental variables.

| Variables | Bio1 | Bio2 | Bio3 | Bio4 | Bio5 | Bio6 | Bio7 | Bio8 | Bio9 | Bio10 | Bio11 | Bio12 | Bio13 | Bio14 | Bio15 | Bio16 | Bio17 | Bio18 | Bio19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bio2 | −0.717 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bio3 | −0.023 | 0.428 | |||||||||||||||||

| Bio4 | −0.613 | 0.373 | −0.652 | ||||||||||||||||

| Bio5 | 0.673 | −0.502 | −0.615 | 0.155 | |||||||||||||||

| Bio6 | 0.944 | −0.735 | 0.169 | −0.817 | 0.417 | ||||||||||||||

| Bio7 | −0.712 | 0.565 | −0.485 | 0.974 | 0.026 | −0.898 | |||||||||||||

| Bio8 | 0.570 | −0.455 | −0.567 | 0.193 | 0.865 | 0.334 | 0.052 | ||||||||||||

| Bio9 | 0.932 | −0.659 | 0.249 | −0.834 | 0.384 | 0.983 | −0.895 | 0.298 | |||||||||||

| Bio10 | 0.761 | −0.612 | −0.576 | 0.044 | 0.982 | 0.528 | −0.105 | 0.887 | 0.493 | ||||||||||

| Bio11 | 0.930 | −0.643 | 0.282 | −0.860 | 0.363 | 0.991 | −0.914 | 0.282 | 0.989 | 0.471 | |||||||||

| Bio12 | 0.661 | −0.701 | −0.016 | −0.578 | 0.293 | 0.734 | −0.665 | 0.173 | 0.699 | 0.377 | 0.705 | ||||||||

| Bio13 | 0.423 | −0.458 | 0.062 | −0.435 | 0.082 | 0.487 | −0.496 | 0.085 | 0.477 | 0.179 | 0.480 | 0.831 | |||||||

| Bio14 | 0.687 | −0.714 | −0.202 | −0.416 | 0.496 | 0.695 | −0.524 | 0.317 | 0.655 | 0.547 | 0.651 | 0.912 | 0.638 | ||||||

| Bio15 | −0.663 | 0.736 | 0.129 | 0.509 | −0.394 | −0.722 | 0.603 | −0.227 | −0.674 | −0.444 | −0.676 | −0.825 | −0.425 | −0.862 | |||||

| Bio16 | 0.498 | −0.531 | 0.114 | −0.552 | 0.078 | 0.589 | −0.610 | 0.018 | 0.574 | 0.179 | 0.582 | 0.905 | 0.969 | 0.709 | −0.555 | ||||

| Bio17 | 0.701 | −0.725 | −0.200 | −0.423 | 0.503 | 0.707 | −0.534 | 0.316 | 0.668 | 0.557 | 0.662 | 0.913 | 0.637 | 0.995 | −0.873 | 0.712 | |||

| Bio18 | 0.369 | −0.408 | 0.176 | −0.501 | −0.036 | 0.478 | −0.543 | 0.060 | 0.462 | 0.067 | 0.480 | 0.816 | 0.948 | 0.598 | −0.456 | 0.927 | 0.593 | ||

| Bio19 | 0.714 | −0.715 | −0.179 | −0.436 | 0.503 | 0.715 | −0.542 | 0.293 | 0.693 | 0.557 | 0.675 | 0.920 | 0.666 | 0.980 | −0.852 | 0.745 | 0.982 | 0.593 |

The Mantel test83 was used to detect the correlation between pairwise Nei’s distance vs. pairwise geographical distance and pairwise Nei’s distance vs. pairwise environmental distance. Matrices of pairwise Nei’s distance and pairwise geographical distance were generated with GenAlEx v6.584. The environmental distance was calculated in NTSYSPC v2.11c85 using the seven identified factors. The Mantel test was performed with program zt86 and 10,000 permutations were used in significance testing.

The correlation between genetic differentiation and geographical/environmental factors were determined by a combination of a partial Mantel test87 and a matrix regression analysis88 using the above distance matrices. A partial Mantel test was performed with program zt86, and 10,000 permutations were used in significance testing. Multiple matrix regression with randomization (MMRR) is a novel and robust approach for estimating the independent effects of potential factors89,90, and the analysis was implemented with 10,000 permutations in R with the MMRR function script88.

Ecological niche modelling (ENM)

Ecological niche modelling was carried out in MAXENT v3.3.343,91 to predict the geographic distribution of climatically suitable habitats for wild soybean. MAXENT calculates probability distributions based on incomplete information and does not require absence data, making it appropriate for modelling species distributions based on presence-only herbarium records43. The sampling sites of 43 populations in combination with 175 presence records obtained from the Chinese Virtual Herbarium (http://www.cvh.org.cn/cms/cn) were included in this study (Table S2, Fig. S4). We employed the 8 aforementioned bioclimatic variables to implement this model. Most of the default parameters of MAXENT were used to conduct ENM, except the following user-selected parameters: application of random seed and random test percentage of 70%, replicates of 10 and bootstrap as the replicated run type. The logistic output of MAXENT consists of a grid map with each cell having an index of suitability between 0 and 1. Low values indicate that conditions are unsuitable for the species, whereas high values indicate that conditions are suitable. Model predictions were visualized in ARCMAP v9.3 (ESRI, Redlands, CA).

To obtain the distribution of wild soybean at the Last Glacial Maximum, we projected present species-climate relationships to the LGM using the Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate (MIRIC v3.2)92 scaled down to a 2.5-arcmin resolution. To explore the importance of each predictor, we carried out Jackknife analyses of the regularized gain using training data. To clarify the possible demographic history of two different lineages (see results), we analysed each of their distributions in the LGM.

To model the suitability of wild soybean in future climates, we applied one commonly used general circulation model, the Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate (MIRIC). The ecological niche modelling predicted with present climatic variables was projected on the global circulation model for the year 2080. The performance of the model prediction was evaluated using the area under the (receiver operation characteristic) curve (AUC) calculated by MAXENT.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: He, S. et al. Environmental and Historical Determinants of Patterns of Genetic Differentiation in Wild Soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. et Zucc). Sci. Rep. 6, 22795; doi: 10.1038/srep22795 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Key Basic Research Program of China (grant no. 2014CB954100-01), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. Y01C541211& 31500459), and a Talent Project of Yunnan Province (grant no. 2011CI042). This study was facilitated by the Germplasm Bank of Wild Species, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. We thank Xinwei Xu and Zhigang Wu for their offer of help in the data analysis.

Footnotes

Author Contributions T.S.Y. and D.Z.L. designed the research, S.L.H. and Y.S.W. conducted the experiment(s), and S.L.H. analysed the results. S.L.H. and T.S.Y. wrote the paper, and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Frankham R. Genetics and extinction. Biol. Conserv. 126, 131–140 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Mayr E. Animal species and evolution. (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1963). [Google Scholar]

- Novembre J. & Stephens M. Interpreting principal component analyses of spatial population genetic variation. Nat. Genet. 40, 646–649 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. et al. Population genetics of Setaria viridis, a new model system. Mol. Ecol. 23, 4912–4925 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt A. et al. The scale of population structure in Arabidopsis thaliana. PloS Genet. 6, e1000843 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J. J. & Coop G. A population genetic signal of polygenic adaptation. PloS Genet. 10, e1004412 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop G., Witonsky D., Di Rienzo A. & Pritchard J. K. Using environmental correlations to identify loci underlying local adaptation. Genetics 185, 1411–1423 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita S. et al. Detecting selection along environmental gradients: analysis of eight methods and their effectiveness for outbreeding and selfing populations. Mol. Ecol. 22, 1383–1399 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier-Level A. et al. A map of local adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 334, 86–89 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M. M., Olivieri I., Waller D. M. & Nielsen E. E. Monitoring adaptive genetic responses to environmental change. Mol. Ecol. 21, 1311–1329 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosil P., Egan S. P. & Funk D. J. Heterogeneous genomic differentiation between walking‐stick ecotypes:“isolation by adaptation’’ and multiple roles for divergent selection. Evolution 62, 316–336 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosil P., Vines T. H. & Funk D. J. Reproductive isolation caused by natural selection against immigrants from divergent habitats. Evolution 59, 705–719 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M. Gene flow and the geographic structure of natural populations. Science 236, 787–792 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S. Isolation by distance. Genetics 28, 114 (1943). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. R. & Mitchell-Olds T. Quantifying effects of environmental and geographical factors on patterns of genetic differentiation. Mol. Ecol. 20, 4631–4642 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibert-Plante X. & Hendry A. P. When can ecological speciation be detected with neutral loci ? Mol. Ecol. 19, 2301–2314 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew R. L., Ostevik K. L., Ebert D. P. & Rieseberg L. H. Adaptation with gene flow across the landscape in a dune sunflower. Mol. Ecol. 21, 2078–2091 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner S. M. genetic and evolution of phenotypic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 24, 35–68 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Sacks B. N., Brown S. K. & Ernest H. B. Population structure of California coyotes corresponds to habitat-specific breaks and illuminates species history. Mol. Ecol. 13, 1265–1275 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Edwards D. L. & Knowles L. L. Integrative testing of how environments from the past to the present shape genetic structure across landscapes. Evolution 67, 3386–3402 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman S. A., McKelvey K. S., Hayden J. & Schwartz M. K. Gene flow in complex landscapes: testing multiple hypotheses with causal modeling. Am. Nat. 168, 486–499 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pease K. M. et al. Landscape genetics of California mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus): the roles of ecological and historical factors in generating differentiation. Mol. Ecol. 18, 1848–1862 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman A. H., Thomassen H. A., Buermann W. & Smith T. B. Genomic signals of diversification along ecological gradients in a tropical lizard. Mol. Ecol. 19, 3773–3788 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca E., Gonzalez-Martinez S. C. & Neale D. B. Environmental versus geographical determinants of genetic structure in two subalpine conifers. New Phytol. 201, 180–192 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. et al. Population structure of the wild soybean (Glycine soja) in China: implications from microsatellite analyses. Ann. Bot. 110, 777–785 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y. X., Fu C. X. & Comes H. P. Plant molecular phylogeography in China and adjacent regions: Tracing the genetic imprints of Quaternary climate and environmental change in the world’s most diverse temperate flora. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 59, 225–244 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy P. et al. Evaluation of genetic structure of Korean wild soybean (Glycine soja) based on saponin allele polymorphism. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 61, 1121–1130 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S., Yu G., Takahara H. & Prentice I. Palaeovegetation (Communications arising): diversity of temperate plants in east Asia. Nature 413, 129–130 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. Paleography of the Ryukyu Islands. Tropics 10, 5–24 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Li F. S. Studies on the ecological and geographical distribution of the Chinese resources of wild soybean. Sci. Agric. Sin. 26, 47–55 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- He S. L., Wang Y. S., Volis S., Li D. Z. & Yi T. S. Genetic diversity and population structure: Implications for conservation of wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. et Zucc) based on nuclear and chloroplast microsatellite variation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 12608–12628 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Tao Y., Zheng S. Z. & Zhou J. L. Isozymatic differentiation in local population of Glycine soja Sieb. and Zucc. Acta Bot. Sin. 37, 669–676 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. J. & Li X. H. Genetic characterization and gene flow in different geographical-distance neighbouring natural populations of wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. & Zucc.) and implications for protection from GM soybeans. Euphytica 186, 817–830 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. et al. A single origin and moderate bottleneck during domestication of soybean (Glycine max): implications from microsatellites and nucleotide sequences. Ann. Bot. 106, 505–514 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai Y. J. studies on the Evolutionary relation among Eco-types of G. max and G. soja in China. Acta Agron. Sin. 26, 513–520 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. J. & Takahata Y. A preliminary comparative evaluation of genetic diversity between Chinese and Japanese wild soybean (Glycine soja) germplasm pools using SSR markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 54, 157–165 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z. X., Zhao T. J., Ding Y. L. & Gai J. Y. Genetic diversity, geographic differentiation and evolutionary relationship among ecotypes of Glycine max and G. soja in China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 54, 4393–4403 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Yan M. F., Li X. H. & Wang K. J. Evaluation of genetic diversity by SSR markers for natural populations of wild soybean (Glycine soja) growing in the region of Beijing, China. J. Plant Ecol. 32, 938–950 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. et al. Population structure of the wild soybean (Glycine soja) in China: implications from microsatellite analyses. Ann. Bot. 110, 777–785 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z. X., Ding Y. L., Zhao T. J. & Gai J. Y. Genetic diversity and peculiarity of annual wild soybean (G. soja Sieb. et Zucc.) from various eco-regions in China. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119, 371–381 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y. S., Zhuang B. C., Zhao L. M., Sun H. & He M. Y. The genetic diversity of annual wild soybeans grown in China. Theor. Appl. Genet. 103, 98–103 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Xu L. H. & Li X. H. Analysis on genetic structure of wild soybean populations by SSRmarkers. Soybean Sci. 30, 41–45 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Phillips S. J., Anderson R. P. & Schapire R. E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 190, 231–259 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Yan J., Zhang G. & Zhou K. Phylogeography and demographic history of Chinese black-spotted frog populations (Pelophylax nigromaculata): evidence for independent refugia expansion and secondary contact. Bmc. Evol. Biol. 8, 21 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa M. et al. Phylogeography of a northeast Asian spruce, Picea jezoensis, inferred from genetic variation observed in organelle DNA markers. Mol. Ecol. 16, 3393–3405 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L. J. et al. Nuclear DNA microsatellites reveal genetic variation but a lack of phylogeographical structure in an endangered species, Fraxinus mandshurica, across north-east China. Ann. Bot. 102, 195–205 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai W. N., Zeng Y. F., Liao W. J. & Zhang D. Y. Flowering phenology and wind-pollination efficacy of heterodichogamous Juglans mandshurica (Juglandaceae). Ann. Bot. 98, 397–402 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins D. G. et al. A meta-analysis of isolation by distance: relic or reference standard for landscape genetics ? Ecography 33, 315–320 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Meirmans P. G. The trouble with isolation by distance. Mol. Ecol. 21, 2839–2846 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburd G. S., Ralph P. L. & Coop G. M. Disentangling the effects of geographic and ecological isolation on genetic differentiation. Evolution 67, 3258–3273 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I. J., Glor R. E. & Losos J. B. Quantifying the roles of ecology and geography in spatial genetic divergence. Ecol. Lett. 16, 175–182 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton J. P., Hangartner S. B. & Hoffmann A. A. Genetic isolation by environment or distance: which pattern of gene flow is most common ? Evolution 68, 1–15 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M. M. et al. Ecotypes of an ecologically dominant prairie grass (Andropogon gerardii) exhibit genetic divergence across the US Midwest grasslands’ environmental gradient. Mol. Ecol. 23, 6011–6028 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer A. & Wolf J. B. Widespread evidence for incipient ecological speciation: a meta-analysis of isolation-by-ecology. Ecol. Lett. 16, 940–950 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I. J. & Bradburd G. S. Isolation by environment. Mol. Ecol. 23, 5649–5662 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manel S. et al. Broad-scale adaptive genetic variation in alpine plants is driven by temperature and precipitation. Mol. Ecol. 21, 3729–3738 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provan J. & Bennett K. Phylogeographic insights into cryptic glacial refugia. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 564–571 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E. et al. Present spatial diversity patterns of Theobroma cacao L. In the neotropics reflect genetic differentiation in Pleistocene refugia followed by human-influenced dispersal. PloS ONE 7, e47676 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltari E. et al. Locating Pleistocene refugia: comparing phylogeographic and ecological niche model predictions. PloS ONE 2, e563 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zonneveld M. et al. Mapping genetic diversity of cherimoya (Annona cherimola Mill.): application of spatial analysis for conservation and use of plant genetic resources. PloS ONE 7, e29845 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell J. et al. Genetic diversity and ecological niche modelling of wild barley: refugia, large-scale post-LGM range expansion and limited mid-future climate threats ? PloS ONE 9, e86021 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel G. et al. Refugia: identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 21, 393–404 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Shoo L. P. et al. Making decisions to conserve species under climate change. Climatic Change 119, 239–246 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y. S. Advances of research on wild soybean in China. J. Jilin Agric. Univ. 30, 394–400 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. J. & Doyle J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J., Lickey E. B., Schilling E. E. & Small R. L. Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: The tortoise and the hare III. Amer. J. Bot. 94, 275–288 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R. & Smouse P. E. GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes 6, 288–295 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K. J. & Muse S. V. PowerMarker: an integrated analysis environment for genetic marker analysis. Bioinformatics 21, 2128–2129 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botstein D., White R. L., Skolnick M. & Davis R. W. Construction of a genetic-linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 32, 314–331 (1980). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L., Smouse P. E. & Quattro J. M. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 131, 479–491 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier Laval G. & Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Ecol. Online 1, 47–50 (2005). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 89, 583–590 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP - phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics 5, 164–166 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J. K., Stephens M. & Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush D., Stephens M. & Pritchard J. K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164, 1567–1587 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earl D. A. & Vonholdt B. M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 4, 359–361 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg N. A. distruct: a program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol. Ecol. Notes 4, 137–138 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Bandelt H. J., Forster P. & R?Hl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 37–48 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Rambaut A., Shapiro B. & Pybus O. G. Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 1185–1192 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe K. H., Li W. H. & Sharp P. M. Rates of nucleotide substitution vary greatly among plant mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNAs. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 9054–9058 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans R. J., Cameron S. E., Parra J. L., Jones P. G. & Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965–1978 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Gormley A. M. et al. Using presence-only and presence-absence data to estimate the current and potential distributions of established invasive species. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 25–34 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N. The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res. 27, 209–220 (1967). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakall R. & Smouse P. E. GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research-an update. Bioinformatics 28, 2537–2539 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R. J. Ntsys-Pc-numerical taxonomy and multivariate-analysis system-version 1.40. Q. Rev. Biol. 64, 250–252 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet E. & Van de Peer Y. zt: a software tool for simple and partial Mantel tests. J. Stat. Softw. 7, 1–12 (2002) [Google Scholar]

- Urban D., Goslee S., Pierce K. & Lookingbill T. Extending community ecology to landscapes. Ecoscience 9, 200–212 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Wang I. J. Examining the full effects of landscape heterogeneity on spatial genetic variation: a multiple matrix regression approach for quantifying geographic and ecological isolation. Evolution 67, 3403–3411 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslee S. C. & Urban D. L. The ecodist package for dissimilarity-based analysis of ecological data. J. Stat. Softw. 22, 1–19 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Yu D., Wang Z., Li X. & Xu X. Great influence of geographic isolation on the genetic differentiation of Myriophyllum spicatum under a steep environmental gradient. Sci. Rep. 5, 15618, doi: 10.1038/srep15618 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips S. J. & Dudik M. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31, 161–175 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hasumi H. & Emori S. K-1 Coupled GCM (MIROC) Description. (Center for Climate System Research, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, 2004). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.