Abstract

Background:

Participation in cancer screening programmes might cause worries in the population outweighting the benefits of reduced mortality. The present study aimed to investigate possible psychological harm of participation in a colorectal cancer (CRC) screening pilot in Norway.

Methods:

In a prospective, randomised trial participants (aged 50–74 years) were invited to either flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) screening, faecal immunochemical test (FIT), or no screening (the control group; 1 : 1: 1). Three thousand two hundred and thirteen screening participants (42% of screened individuals) completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire as well as the SF-12—a health-related quality of life (HRQOL) questionnaire when invited to screening and when receiving the screening result. A control group was invited to complete the questionnaires only. Two thousand six hundred and eighteen control participants (35% of invited individuals) completed the questionnaire.

Results:

A positive screening result did not increase participants' level of anxiety or depression, or decrease participants' level of HRQOL. Participants who received a negative result reported decreased anxiety and improvement on some HRQOL dimensions. However, no change was considered to be of clinical relevance.

Conclusion:

The current study showed no clinically relevant psychological harm of receiving a positive CRC screening result or of participating in FS or FIT screening, in a Norwegian population.

Keywords: Colorectal Cancer Screening, Flexible Sigmoidoscopy, Faecal Immunochemical Test, Anxiety, Health-Related Quality of Life

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most frequent cause of cancer-related deaths in men and third in women in developed countries (Torre et al, 2015). Randomised controlled trials have demonstrated that screening for CRC can reduce CRC incidence and/or mortality (Atkin et al, 2010; Holme et al, 2013, 2014), but the total benefit and harm of national cancer screening programmes are under debate. Saving relatively few lives requires a large number of people to be screened (Atkin et al, 2010). The vast majority of participants will never develop cancer, but may be exposed to potential psychological stress by participation. On a population level, negative psychological effects can counterbalance the benefits of reduced cancer incidence and mortality. Therefore, investigating the psychological effects is an important part of determining potential harms of a screening programme.

Cancer is one of the largest threats to peoples' health, and participating in screening for cancer might therefore cause anxiety (Miles and Wardle, 2006). Several studies report more anxiety in participants who receive a positive faecal immunochemical test (FIT) or faecal occult blood test (FOBT) result (Parker et al, 2002; Brasso et al, 2010; Denters et al, 2013; Bobridge et al, 2014; Laing et al, 2014). However, this effect seems to diminish (Bobridge et al, 2014) or disappear (Parker et al, 2002; Brasso et al, 2010; Laing et al, 2014) with long-term follow-up. Other studies report no psychological harm of participation in CRC screening (Niv et al, 2012; Robb et al, 2013). Further, some evidence exists for positive effects of CRC screening participation, such as reduced anxiety (Thiis-Evensen et al, 1999; Wardle et al, 2003), and improved health-related quality of life (HRQOL) (Taupin et al, 2006; Pizzo et al, 2011). Possible reasons for this inconsistency may be due to the different design of the studies, for example lack of baseline measure or control groups, as well as the use of different instruments to measure psychological effects. The current study is designed to overcome some of these challenges.

In Norway, CRC incidence has nearly tripled since the 1950s (Bray et al, 2007), and the lifetime risk for the average population to develop CRC is about 6% (Bretthauer et al, 2006). Regardless, no national screening programme for CRC exists. Therefore, the randomised management study Bowel Cancer Screening in Norway—a pilot of a national programme (the BCSN pilot), was started in 2012 to compare the effect of the two different screening modalities FIT and flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) on reduction in CRC incidence and mortality (Bretthauer and Hoff, 2012).

To evaluate the psychological effects of participation in the BCSN pilot in the Norwegian population, a sub-study was started where a random sample of the original cohort was invited to participate. Our hypothesis was that participants who receive a positive screening result, will experience more anxiety and reduced HRQOL, whereas participants who receive negative screening results will report anxiety and HRQOL scores similar to their baseline levels. The primary aim of the present sub-study was to measure short-term changes in participants' level of anxiety, depression and HRQOL during screening participation; from before screening to receipt of the screening result. Demographical variables are known to influence both anxiety and HRQOL (Loge and Kaasa, 1998; Bjelland et al, 2008, 2009). The secondary aim was to explore if participation in CRC screening affect demographical groups differently.

Materials and Methods

In the BCSN pilot, 140 000 men and women aged 50–74 years in two defined geographical areas in South-East Norway are invited. During 2012–2018 they are randomised to receive an invitation to either a once only FS examination or biennial screening with FIT (1 : 1). Individuals randomised to FIT receive a kit for taking a stool sample together with a prepaid return envelope to send the sample for analysis. Participants with a positive screening result in both modalities are invited to a work-up colonoscopy examination. In the current sub-study, we invited a sub-sample of those invited to the main study.

Participants were invited every other week starting in September 2013 until July 2014 (FS group) and from October 2013 until December 2013 (FIT group). All participants received a psychological questionnaire with the invitation, together with a letter asking them to complete and return the questionnaire by a prepaid return envelope or complete the questionnaire online. Participants were informed that non-participation in the questionnaire study would not have consequences for their opportunity of screening participation. A reminder was sent to participants who did not complete FIT screening or attend the FS examination, but this reminder did not include the psychological questionnaires. Nonresponders of the questionnaire were not reminded to complete the questionnaire. A control group of sex- and age-matched individuals living in the neighbouring counties were randomly drawn from the Norwegian National Registry and invited to participate in the questionnaire study only. Invitations to this control group were sent once per month.

Definitions

A positive FS is defined as detection of advanced neoplasia (CRC, adenoma ⩾10 mm, three or more adenomas, any polyp⩾10 mm, adenoma with high-grade dysplasia or villous components) with subsequent referral to colonoscopy. As we were interested in the effect of a positive screening result, participants diagnosed with CRC at the FS examination were excluded from the analysis. A positive FIT screening result is defined as detection of human blood in the stool sample (cutoff>75 ng ml−1) with subsequent referral to colonoscopy.

Questionnaires

Two patient-reported outcome questionnaires were utilised in this study; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS), and the Short-Form Health Survey 12 (SF-12), a generic HRQOL questionnaire. Both questionnaires have been translated into Norwegian and validated in Norwegian background populations (Loge and Kaasa, 1998; Loge et al, 1998; Olsson et al, 2005).

HADS consists of 14 questions, 7 measuring anxiety and 7 measuring depression (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983). Each question has the same four response options, ranging from 0–3, with a maximum total score of 21 for each scale. A higher score indicates higher levels of anxiety or depression. Cutoff levels are defined as a score of ⩾8 for possible presence, and ⩾11 for probable presence of ‘clinically meaningful degrees of mood disorder's. In the current study, a score of ⩾8 was defined as cutoff for caseness in HADS-anxiety and HADS-depression, based on the results from a study performed on Norwegian patients attending primary care physicians (Olsson et al, 2005). For participants lacking one or two items on one subscale, the missing values were substituted by the mean of the completed item scores. The subscale of participants lacking more than two items was set to missing.

SF-12 consists of 12 questions; each question has response choices varying from 2 to 6 alternatives (Ware et al, 1996). The 12 questions can be transformed to 8-dimensional scores covering the physical and mental aspects of HRQOL. The dimensions are Physical Functioning, Role Physical (limitation associated with physical problems), Role Emotional (limitations associated with emotional problems), Mental Health, General Health (GH), Bodily Pain (BP), Vitality (energy and happiness, VT), and Social Functioning (SF). The dimension scores range from 0 to 100, with higher score indicating better HRQOL. Missing values were imputed following the recommendations of Ware and Kosinski (2001). If it was impossible to compute the value for one dimension, then that dimensional score was set to missing.

Participants

The number of individuals invited to the psychological questionnaire study was 7270 in the FS group, 7024 in the FIT group, and 7650 in the control group, respectively. Criteria for inclusion in the analyses were completion of the baseline and result questionnaire, as well as completion of the screening test for FS and FIT participants.

Participants were ineligible for inclusion in the analysis if participants (a) had a previous CRC diagnosis, or (b) were deceased. Unattainable participants (invitation returned to sender), and participants who had moved out of the county were excluded. This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of South-East Norway (REK approval no 2011/1272). Participants gave their consent to participate in the questionnaire study by completing and returning the mailed questionnaire.

Study outline

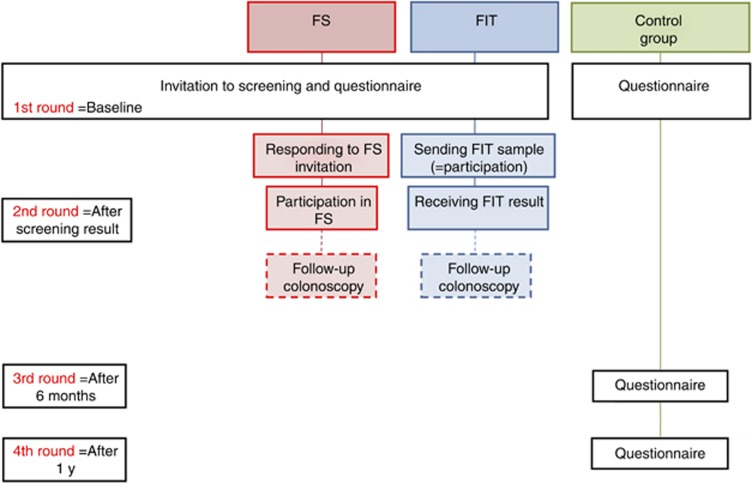

Participants' levels of anxiety, depression and HRQOL were measured before and after screening participation. First participants received the questionnaire with the invitation to screening (baseline measure). They received the questionnaire the second time together with the results of their primary screening test (result measure), but before potential colonoscopy, (see Figure 1). FS participants received the second questionnaire when they were informed about the result of the examination by an endoscopist, whereas FIT participants and FS participants who had a histology sample analysed received a letter with their results together with the second questionnaire. Control participants completed the questionnaire at baseline only.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of questionnaire measures in the FS-, FIT- and control group. First and second round illustrate data collection in the current study. y, years.

The date of completion of the questionnaire was used to determine whether it had been completed before or after screening compliance. Consequently, participants with a questionnaire lacking completion date were excluded. Further, we were interested in short-term reactions of the primary screening test result, and therefore participants completing the questionnaire >60 days following the primary screening result, or participants who completed the questionnaire after work-up colonoscopy were also excluded.

Information regarding participants' nationality, marital status, education, and occupation were obtained through the questionnaire. Education level was classified as low (primary school/high school) or high (minimum 2 years of college/university studies). Information regarding age and gender were obtained from the Norwegian National Registry.

Statistical analysis

Internal consistency for the two HADS subscales were tested by Cronbach's alpha. To investigate demographical differences between the three groups before screening, χ2-tests were applied for categorical outcomes. Standardised residuals show where the statistical differences lie. Analysis of variance was applied to test for group differences on continuous demographical outcomes.

To compare FIT and FS participants with the control group on anxiety, depression, and HRQOL at baseline ANOVA analyses were applied. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, and work. Significant difference in the ANOVA analysis was further probed by contrast analysis, to see which groups differed from each other. ANOVA was used to test for two- and three-way interaction effects between time (baseline and result), screening group (FIT and FS) and screening result (positive and negative) on the outcome variables. Age, sex, education, marital status, and work were included in the model to adjust for the effect of these variables. This analyses also allowed us to investigate interaction effects between screening result and demographic variables on the outcome measures. We compared the mean change scores from baseline to result between groups with positive and negative screening results. This analysis were completed with and without adjustment for participants' baseline values on the outcome. McNemars test was applied to test for changes in prevalence of participants with cutoff levels of anxiety and depression from baseline to result.

To adjust for multiple comparisons we used a Benjamini–Hochberg correction with a false discovery rate of 15%. Thus, the BH rejection treshold P⩽0.01 were considered statistically significant (Benjamini et al, 2001). Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software IBM SPSS v19 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Criteria for clinically relevant change was defined as a change of ½ s.d. (Norman et al, 2003), the smallest change perceived by individuals as an actual change in condition. Cohen classified different effect sizes, and defined a Cohens d effect size above 0.5 as a medium effect size, or a clinically relevant change (Cohen, 1969). Therefore, our second criteria for clinically relevant change was a Cohens d above 0.5.

Results

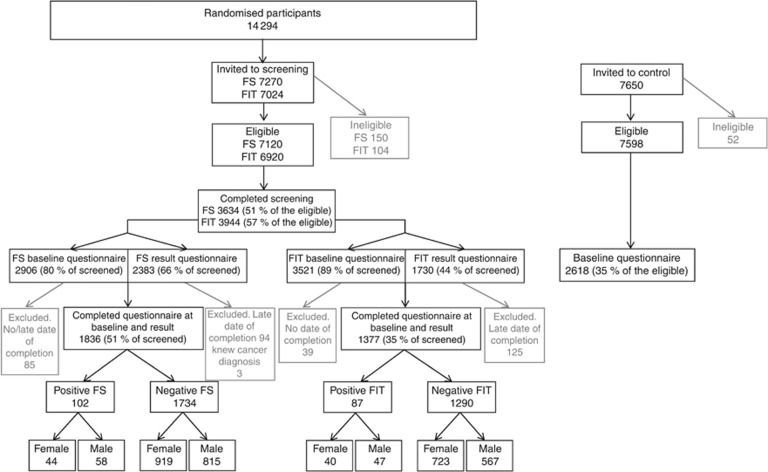

Of the 14 294 individuals randomised to screening and invited to complete the questionnaires, 7578 (53%) completed screening. Of these, 3216 (42%) completed the questionnaire both at invitation and after receiving the screening result; 1839 in the FS group and 1377 in the FIT group. Three participants in the FS group learned their diagnosis of cancer at the FS examination, and were excluded from the analysis. In the control group, 2618 individuals (35% of the invited) completed the baseline questionnaire (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow-chart showing screening participation and questionnaire response rate for FS-, FIT-, and the control group.

Table 1 depicts demographical data in each randomised group. Contrast analyses revealed that the FS group had a higher mean age (M=63.7 years, s.d.=7.0) compared with the FIT group (M=62.9 years, s.d.=6.6), P<0.01 and compared with the control group (M=62.4 years, s.d.=6.8), P<0.01. The mean age of the FIT group was higher compared with the control group P<0.01. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in proportion of participants' gender.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the three groups measured at baseline.

| FS (std residual) | FIT (std residual) | Control (std residual) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norwegian nationality, % | 95.4% (0.2) | 94.5% (−0.2) | 94.9% (−0.1) | 0.45 |

| Not married/cohabitant, % | 18.2% (−2.9)a | 21.5% (0.1) | 23.4% (2.3)a | <0.01 |

| Higher education, % | 43.3% (−1.6) | 41.4% (−2.4)a | 50.0% (3.0)a | <0.01 |

| Working, % | 47.0% (−1.6) | 45.7% (−2.0)a | 53.6% (2.8)a | 0.01 |

| Women, % | 52.3% (−0.8) | 55.4% (0.9) | 53.8% (0.0) | 0.22 |

| Mean age, years | 63.7 | 62.9 | 62.4 | <0.01b |

Abbreviations: ANOVA=analysis of variance; FS=flexible sigmoidoscopy; FIT=faecal immunochemical test.

Chi-square test.

The bold values illustrate that the P-value reached criteria for statistical significance.

Standardised residuals outside ±1.96 is considered statistically significantly.

ANOVA.

The HADS-anxiety and the HADS-depression subscales had good internal consistency with Cronbach alpha coefficients of 0.86 and 0.84, respectively. At baseline there were no differences exceeding the criteria for a clinically relevant difference in anxiety, depression or HRQOL between participants in the FS, FIT, and control groups (Table 2).

Table 2. HADS-anxiety, HADS-depression and SF-12 mean scores in the three groups prior screening (baseline).

| FS (s.d.) | FIT (s.d.) | Control (s.d.) | P-valuea | P-valueb FS vs Control (Cohens d) | P-valueb FIT vs Control (Cohens d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HADS | ||||||

| Anxiety | 3.20 (3.07) | 3.64 (3.53) | 3.68 (3.58) | <0.01 | <0.01 (0.1) | 0.75 |

| Depression | 2.31 (2.63) | 2.63 (3.09) | 2.63 (3.00) | <0.01 | <0.01 (0.1) | 0.98 |

|

SF-12 | ||||||

| Physical Functioning | 87.5 (23.6) | 85.9 (26.0) | 87.2 (23.3) | 0.12 | ||

| Role Physical | 85.1 (34.4) | 82.1 (37.0) | 82.3 (34.8) | 0.01 | 0.01 (−0.1) | 0.89 |

| Role Emotional | 89.8 (28.0) | 87.8 (30.6) | 85.7 (32.3) | <0.01 | <0.01 (−0.1) | 0.04 (−0.1) |

| Mental Health | 83.4 (17.0) | 80.7 (18.6) | 80.5 (19.3) | <0.01 | <0.01 (−0.2) | 0.72 |

| General Health | 70.0 (22.6) | 70.0 (24.2) | 70.1 (24.4) | 0.99 | ||

| Bodily Pain | 84.6 (22.5) | 83.4 (23.5) | 83.1 (23.0) | 0.09 | ||

| Vitality | 62.8 (25.6) | 61.5 (26.3) | 61.0 (26.3) | 0.07 | ||

| Social Functioning | 91.4 (17.5) | 88.6 (21.0) | 88.2 (21.7) | <0.01 | <0.01 (−0.1) | 0.56 |

Abbreviations: ANOVA=analysis of variance; FS=flexible sigmoidoscopy; FIT=faecal immunochemical test; HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

The bold and italics values illustrate that the P-value reached criteria for statistical significance.

ANOVA adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status, and work.

Contrast analysis probing the significant ANOVA effect. A Cohens d above 0.5 is considered clinically relevant.

Anxiety and depression

Results from the ANOVA analyses with time (baseline and result), screening group (FIT and FS) and screening result (positive and negative) as predictors are shown in Table 3. Participants with positive FS and FIT screening results increase slightly in anxiety from baseline to result, but the effect was not statistically significant. FS negative and FIT-negative report a statistically significant decrease in anxiety from baseline to result. The interaction effect of time, screening group, and screening result was not statistically significant (P=0.89).

Table 3. Mean HADS-anxiety and HADS-depression score at baseline and at result, and change scores from baseline to result, for participants with positive and negative screening results.

|

Positive screening result |

Negative screening result |

Positive

vs

negative |

Positive

vs

negative |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean baseline (s.d.) | Mean result (s.d.) | P-valuea | Mean baseline (s.d.) | Mean result (s.d.) | P-valuea | Change score positive | Change score negative | P-valueb change scores | Change score positive | Change score negative | P-valuec change scores | |

|

Anxiety | ||||||||||||

| FS | 3.26 (2.42) | 3.45 (2.66) | 0.29 | 3.31 (2.39) | 3.17 (2.39) | <0.01 | 0.19 (1.64) | −0.14 (1.60) | 0.08 | 0.16 (1.65) | −0.16 (1.60) | 0.08 |

| FIT | 3.13 (2.49) | 3.31 (2.58) | 0.40 | 3.55 (2.41) | 3.36 (2.41) | <0.01 | 0.18 (1.74) | −0.19 (1.73) | 0.10 | 0.12 (1.74) | −0.16 (1.72) | 0.21 |

|

Depression | ||||||||||||

| FS | 2.55 (2.13) | 2.31 (2.27) | 0.14 | 2.43 (2.00) | 2.36 (2.39) | 0.09 | −0.24 (1.45) | −0.07 (1.60) | 0.30 | −0.22 (1.45) | −0.07 (1.60) | 0.35 |

| FIT | 2.99 (2.08) | 2.65 (2.16) | 0.07 | 2.47 (2.06) | 2.49 (2.06) | 0.63 | −0.34 (1.50) | 0.02 (1.37) | 0.06 | −0.23 (1.50) | 0.02 (1.37) | 0.17 |

Abbreviations: ANOVA=analysis of variance; FS=flexible sigmoidoscopy; FIT=faecal immunochemical test; HADS=Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

All analyses adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status and work (and the other HADS-score).

The bold and italics values illustrate that the P-value reached criteria for statistical significance.

ANOVA.

ANOVA with change score from baseline to result as outcome variable.

ANOVA with change score from baseline to result as outcome variable, adjusted for baseline value.

Participants receiving a positive or negative FS or FIT screening result did not report a statistically significant change in depression from baseline. There was no statistically significant change in the prevalence of screening participants who scored above cutoff levels for caseness of anxiety or depression from baseline to results (Table 4).

Table 4. Prevalence of participants scoring above 8, cutoff level indicating possible presence of anxiety and depression.

| ⩾8 anxiety baseline | ⩾8 anxiety result | P-value | |

| FS positive | 14.9% n=15 | 16.8% n=17 | 0.75 |

| FS negative | 9.8% n=164 | 9.7% n=161 | 0.84 |

| FIT positive | 18.8% n=16 | 15.3% n=13 | 0.45 |

| FIT negative | 13.7% n=171 | 12.9% n=161 | 0.33 |

| ⩾8 depression baseline | ⩾8 depression result | P-value | |

| FS positive | 10.1% n=10 | 7.1% n=7 | 0.25 |

| FS negative | 5.4% n=92 | 6.0% n=102 | 0.29 |

| FIT positive | 19.0% n=16 | 16.7% n=14 | 0.68 |

| FIT negative | 7.8% n=97 | 8.4% n=105 | 0.39 |

Abbreviations: FS=flexible sigmoidoscopy; FIT=faecal immunochemical test.

McNemars test.

A marginally significant interaction effect between gender and screening result was observed for changes in anxiety, (P=0.03) and a statistically significant effect was observed for depression, (P<0.01). Participants who received negative results showed little effect of gender (women M=−0.21, men M=−0.11), whereas in the positive result group, women reported increased anxiety (M=0.49) whereas men reported a decrease (M=−0.05). Among the negatives, there was little effect of gender on depression (women M=−0.03, men M=−0.01), whereas among the positives men reported a decrease (M=−0.69) and women an increase (M=0.19).

Health-related quality of life

No interaction effects were statistically significant for HRQOL. No statistically significant changes were observed for participants who received a positive screening result. For FS negative, a statistically significant improvement in the dimensions GH, BP, and VT was observed from baseline to receipt of the result (Table 5a). Further, FIT-negative participants reported a statistically significant improvement in VT (Table 5b).

Table 5a. Mean HRQOL at baseline and at result and change scores from baseline to result for FS participants with positive and negative screening results.

|

Positive screening result |

Negative screening result |

Positive

vs

Negative |

Positive

vs

Negative |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12 | Mean baseline (s.d.) | Mean result (s.d.) | P-valuea | Mean baseline (s.d.) | Mean result (s.d.) | P-valuea | Change score positive | Change score negative | P-valueb change scores | Change score positive | Change score negative | P-valuec change scores |

|

FS | ||||||||||||

| PF | 86.7 (22.6) | 84.1 (22.1) | 0.09 | 87.0 (23.1) | 87.4 (25.9) | 0.38 | −2.6 (14.5) | 0.4 (16.0) | 0.06 | −2.5 (14.0) | 0.5 (14.0) | 0.04 |

| RP | 84.2 (33.9) | 84.6 (33.9) | 0.91 | 84.5 (31.9) | 83.9 (31.9) | 0.41 | 0.4 (28.1) | −0.6 (27.9) | 0.76 | 0.7 (14.9) | −0.2 (14.8) | 0.75 |

| RE | 81.7 (27.2) | 85.7 (28.1) | 0.16 | 90.2 (27.9) | 89.9 (27.9) | 0.68 | 4.0 (27.1) | −0.3 (27.9) | 0.14 | 0.6 (26.0) | −0.3 (26.0) | 0.90 |

| MH | 83.4 (17.4) | 81.7 (17.5) | 0.24 | 83.6 (16.0) | 84.3 (16.0) | 0.03 | −1.7 (12.6) | 0.7 (12.0) | 0.09 | −1.3 (12.3) | 1.1 (12.0) | 0.07 |

| GH | 69.4 (21.3) | 69.5 (21.3) | 0.98 | 69.5 (20.0) | 72.1 (20.0) | <0.01 | 0.1 (13.6) | 2.6 (16.0) | 0.08 | 0.03 (12.8) | 2.6 (12.8) | 0.06 |

| BP | 82.9 (21.4) | 85.4 (21.6) | 0.12 | 84.5 (25.1) | 85.7 (22.4) | <0.01 | 2.5 (15.5) | 1.2 (16.0) | 0.45 | 2.3 (14.7) | 1.4 (14.8) | 0.57 |

| VT | 62.5 (24.2) | 62.9 (24.2) | 0.93 | 62.9 (25.1) | 65.3 (24.7) | <0.01 | 0.4 (18.4) | 2.4 (20.0) | 0.33 | 0.5 (17.2) | 2.5 (17.3) | 0.27 |

| SF | 87.8 (18.4) | 87.9 (17.7) | 0.90 | 91.5 (18.8) | 92.2 (18.0) | 0.09 | 0.1 (15.5) | 0.7 (16.0) | 0.72 | −0.8 (13.6) | 1.27 (14.0) | 0.17 |

Abbreviations: ANOVA=analysis of variance; PF=Physical Functioning; RP=Role Physical; RE=Role Emotional; MH=Mental Health; GH=General Health; BP=Bodily Pain; VT=Vitality; SF=Social Functioning.

All analyses adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status and work

The bold and italics values illustrate that the P-value reached criteria for statistical significance.

ANOVA.

ANOVA with change score from baseline to result as outcome variable.

Change score from baseline to result as outcome variable, adjusted for baseline value of the outcome.

Table 5b. Mean HRQOL at baseline and at result and change scores from baseline to result for FIT participants with positive and negative screening results.

|

Positive screening result |

Negative screening result |

Positive

vs

Negative |

Positive

vs

Negative |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-12 | Mean baseline (SD) | Mean result (SD) | P-valuea | Mean baseline (SD) | Mean result (SD) | P-valuea | Change score positive | Change score negative | P-valueb change scores | Change score positive | Change score negative | P-valuec change scores |

| FIT | ||||||||||||

| PF | 79.5 (27.2) | 80.1 (26.6) | 0.72 | 85.8 (26.7) | 85.2 (26.3) | 0.17 | 0.6 (15.0) | −0.6 (13.7) | 0.51 | −0.9 (14.2) | −0.7 (14.1) | 0.88 |

| RP | 73.8 (39.7) | 74.6 (40.7) | 0.84 | 82.0 (35.9) | 80.8 (39.9) | 0.14 | 0.8 (28.2) | −1.2 (27.5) | 0.58 | 2.4 (15.0) | −1.6 (15.1) | 0.80 |

| RE | 85.1 (32.9) | 77.2 (33.9) | 0.02 | 87.8 (31.9) | 86.6 (31.9) | 0.13 | −7.9 (28.2) | −1.2 (27.5) | 0.06 | −9.6 (26.2) | −1.7 (26.1) | 0.01 |

| MH | 79.4 (20.4) | 78.9 (20.4) | 0.76 | 80.8 (19.5) | 81.6 (20.0) | 0.03 | 0.5 (13.3) | 0.8 (13.7) | 0.83 | 0.4 (12.0) | 0.3 (12.0) | 0.61 |

| GH | 66.4 (25.2) | 64.2 (25.2) | 0.18 | 69.8 (23.9) | 69.7 (23.9) | 0.86 | −2.2 (14.1) | −0.1 (13.7) | 0.21 | −2.9 (13.0) | −0.1 (13.0) | 0.07 |

| BP | 79.3 (25.5) | 80.8 (26.0) | 0.45 | 83.5 (25.5) | 83.1 (25.9) | 0.40 | 1.5 (15.8) | −0.4 (17.2) | 0.35 | 0.3 (14.9) | −0.5 (14.8) | 0.66 |

| VT | 58.9 (29.9) | 60.4 (29.5) | 0.50 | 61.7 (29.1) | 63.5 (28.7) | <0.01 | 1.5 (19.1) | 1.8 (17.2) | 0.91 | 0.5 (17.4) | 1.6 (17.1) | 0.62 |

| SF | 84.6 (21.6) | 89.1 (20.9) | 0.02 | 88.8 (21.6) | 89.2 (21.2) | 0.34 | 4.5 (15.8) | 0.4 (17.2) | 0.03 | 2.4 (13.9) | 0.1 (14.1) | 0.15 |

All analyses adjusted for age, sex, education, marital status and work

The bold and italics values illustrate that the P-value reached criteria for statistical significance.

ANOVA.

ANOVA with change score from baseline to result as outcome variable.

Change score from baseline to result as outcome variable, adjusted for baseline value of the outcome.

A significant interaction effect was observed between gender and screening result on the RE dimension, (P<0.01). There was little effect of gender among participants with negative screening results (RE women M=−1.2, men M=−0.3). Among the positives, women report an increase in RE (M=5.4), whereas men report a large decrease in the RE dimension (M=−8.0).

To assess whether nonresponders to the result questionnaire were different to responders we repeated the analyses with baseline scores carried forward, for participants who did not reply to the result questionnaire. However, the analyses including these participants yielded similar results.

As can be observed from comparing change scores towards s.d. in Tables 3, 5a and 5b, none of the observed changes fulfilled the first criteria of a clinically relevant change, (=change of ½ s.d.). Further, comparing the screening groups at result with the control group at baseline, no comparison indicated a medium effect size, defined as a Cohens d above 0.5.

Discussion

This study indicates no clinically relevant psychological harm of receiving a positive CRC screening result. Changes in anxiety, depression and HRQOL were measured from before screening to after knowing the screening results in a large number of asymptomatic participants. A positive screening result did not increase participants' level of anxiety or depression, or decrease participants' level of HRQOL. Further, participants who received a negative screening result reported a statistically significant decrease in anxiety, and improvements in the HRQOL dimensions GH, BP, and VT. However, no changes observed in the current study reached the criteria of clinical relevance. Altogether, these results indicate no clinically relevant psychological harm of participation in FIT or FS screening delivered in a pilot for a national screening programme. The randomised design combined with a control group gives confidence in generalisation of the results.

The literature is inconsistent regarding psychological effects of CRC screening. The results from the current study are in congruence with some previous research showing no negative effect on anxiety (Wardle et al, 2003; Robb et al, 2013) or HRQOL (Niv et al, 2012) from baseline to receipt of FS and colonoscopy screening results. However, four other studies reported anxiety in FIT-/FOBT-positive participants (Brasso et al, 2010; Denters et al, 2013; Bobridge et al, 2014; Laing et al, 2014). Importantly, three of the studies (Brasso et al, 2010; Denters et al, 2013; Bobridge et al, 2014) did not report changes from baseline to result within groups, and thus can only document a statistically significant difference in anxiety between participants who receive different screening results, after the screening examination. However, an observed difference between recipients of different screening results may exist before screening, rather than the knowledge of the screening result causing psychological distress (Mccaffery and Barratt, 2004). As a result, this study emphasises the importance of a baseline measure to document changes within participants. Second, the last study showing anxiety as a consequence of CRC screening participation (Laing et al, 2014) documents an increase in mean anxiety score from baseline in FOBT-positive participants. However, the study shows an increase of 5% on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory measure. Research shows that an effect of 20% change in the HADS scale (Puhan et al, 2008), or a difference of ½ s.d. (Norman et al, 2003) in other psychosocial measures, is needed for the individual to experience the change as meaningful. The effect documented in the study by Laing et al (2014), as well as all changes observed in the current study, do not fulfil this criteria for a clinically relevant change. Consequently, there seems to be little support for the concern that CRC screening causes clinically relevant anxiety.

In contrast to previous studies, the current study investigated whether anxiety depended on the type of screening test. Anxiety depended on which result one received, but was not influenced by whether participants completed FIT or FS screening. Thus, our study provides important knowledge for planning new screening programmes.

The study employed HADS, a validated measure of generic anxiety. A meta-analyses on breast cancer screening concluded that false-positive mammograms cause distress in participants, but that cancer-specific anxiety measures detect the effect, whereas generic anxiety measures do not (Salz et al, 2010). As Broderson (Brodersen et al, 2007) argues, generic scales may measure constructs unlikely to be relevant to a screening experience. Consequently, we cannot exclude the possibility that a cancer-specific measure would yield different results. However, several studies have been able to document effects of CRC screening on anxiety using generic measures (Brasso et al, 2010; Bobridge et al, 2014; Laing et al, 2014). To replicate our findings with a cancer-specific measure is an important issue for future research. To enable these studies, development of a validated CRC-specific anxiety measure is needed.

Most research on psychological reactions towards cancer screening stem from studies with female participants (Bond et al, 2013; O'connor et al, 2015). One study showed that men report lower screening-specific anxiety in CRC screening compared with women (Denters et al, 2013), whereas other studies report no gender difference (Wardle et al, 2003; Taylor et al, 2004). The marginally significant effect of gender in the present study indicates that a positive screening result might have a larger influence on anxiety in women than in men. One explanation could be that groups who report higher initial levels of anxiety are more influenced by threatening experiences such as receiving a positive screening result. Further, women report more pain than men during endoscopy, which is related to anatomical differences (Thiis-Evensen et al, 2000). Pain during screening examination is related to increased anxiety following screening (Hafslund, 2000). The trend observed in our study indicate that the reactions towards a positive screening result could differ depending on gender. This is an important finding that warrants future research.

Research on psychological effects of screening has focused on the experience of a false-positive screening result. However, the most frequent screening experience is to receive a true-negative result. The current study shows decreased anxiety and improvements in some dimensions of HRQOL as a consequence of receiving a negative result, in line with previous research (Thiis-Evensen et al, 1999; Wardle et al, 2003; Taupin et al, 2006; Pizzo et al, 2011). One possible explanation is that an invitation for CRC screening may increase initial anxiety levels measured at baseline. However, Wardle et al (1999) showed that receiving information about FS screening did not cause increased anxiety levels. Further, participants in both screening groups were similar to the control participants at baseline, and thus do not support this hypothesis. However, decreased anxiety may result from a perceived decreased risk of CRC (Robb et al, 2004), an important motivation for health behaviour (Brewer et al, 2007).

In order to improve studies of psychosocial outcomes in screening, recommendations have been made to include both a baseline measure and a control group (Mccaffery and Barratt, 2004). Only one other study of CRC screening has adhered to the recommendations (Taylor et al, 2004). However, in this study participants completed several screening programmes, making it difficult to disentangle the effect of a positive CRC screening result alone. Further, the present study has the largest participant sample of the two studies. A large sample is necessary to enable both a prospective design including a baseline measure, while ensuring a large enough number of responding participants with a positive result to enable investigation of changes within this group. Comparing screening participants with a control group determine that CRC screening participants were similar to a normal population at baseline, which enables generalisation of the results.

While the control group is a strength in the current study, unfortunately the response rate in the control group was low. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the sample of control participants who complete the questionnaire differ from those who do not, and consequently the control group might not be representative of the normal population as a whole. However, control participants were not very different from a large number of screening participants before screening on demographic variables as well as anxiety, depression and HRQOL. Before an intervention screening participants are likely to be similar to the normal population.

Owing to the design of the current study the number of participants with a positive screening result is low. The increase in mean anxiety score in participants with a positive screening result is of similar size as the decreased anxiety in screening negative participants. The latter sample was larger and therefore statistically significant results are more easily detectable. However, neither change was close to a clinically relevant change. Another limitation in the present study is the low percentage of participants complying with both the screening examination and two questionnaires. Individuals who do choose to participate in CRC screening may differ from the participants who decline participation. CRC screening attenders are more often married (Van Jaarsveld et al, 2006), have higher socioeconomic status (Pornet et al, 2010) and better mental health (Kodl et al, 2010) compared with nonattendees. These participants might respond differently towards a positive screening result, compared with participants with lower levels of social support, lower health literacy, or initial psychological distress. Further, it is possible that participants who complied with both questionnaires differ from nonrepliers, for instance by being more positive towards screening. Therefore, the results might not be generalised to the population as a whole. However, comparison with the control group indicates that the screening participants were similar on anxiety, depression and HRQOL as the general population before screening.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study shows no increase in anxiety or depression or decrease in HRQOL in participants who received a positive CRC screening result. Moreover, participants who received a negative result report lower levels of anxiety, and improvement on some HRQOL dimensions. However, no changes observed in the current study were considered to be of clinical relevance. Thus, receiving a positive CRC screening result, and participating in CRC screening does not seem to have clinically relevant short-term effects on anxiety, depression, or HRQOL in Norwegian participants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anita Jørgensen, Chloé Beate Steen, Catherine Stenstad and the dedicated doctors and nurses at Bærum Hospital and Østfold Hospital who made the pilot possible. This study was funded by the Ministry of Health and Care Services in Norway. Clinical trial registration number: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01538550.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

References

- Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, Wooldrage K, Hart AR, Northover JM, Parkin DM, Wardle J, Duffy SW, Cuzick J (2010) Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 375: 1624–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I (2001) Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res 125: 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Krokstad S, Mykletun A, Dahl AA, Tell GS, Tambs K (2008) Does a higher educational level protect against anxiety and depression? The HUNT study. Soc Sci Med 66: 1334–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Lie SA, Dahl AA, Mykletun A, Stordal E, Kraemer HC (2009) A dimensional versus a categorical approach to diagnosis: anxiety and depression in the HUNT 2 study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 18: 128–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobridge A, Bampton P, Cole S, Lewis H, Young G (2014) The psychological impact of participating in colorectal cancer screening by faecal immuno-chemical testing—the Australian experience. Br J Cancer 111: 970–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond M, Pavey T, Welch K, Cooper C, Garside R, Dean S, Hyde C (2013) Systematic review of the psychological consequences of false-positive screening mammograms. Health Technol Assess 17: 1–170, v-vi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasso K, Ladelund S, Frederiksen BL, Jorgensen T (2010) Psychological distress following fecal occult blood test in colorectal cancer screening—a population-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol 45: 1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F, Wibe A, Dorum LM, Moller B (2007) [Epidemiology of colorectal cancer in Norway]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 127: 2682–2687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretthauer M, Ekbom A, Malila N, Stefansson T, Fischer A, Hoff G, Weiderpass E, Tretli S, Trygvadottir L, Storm H, Holten I, Adami HO (2006) [Politics and science in colorectal cancer screening]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 126: 1766–1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretthauer M, Hoff G (2012) Comparative effectiveness research in cancer screening programmes. BMJ 344: e2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer NT, Chapman GB, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Mccaul KD, Weinstein ND (2007) Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: the example of vaccination. Health Psychol 26: 136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen J, Mckenna SP, Doward LC, Thorsen H (2007) Measuring the psychosocial consequences of screening. Health Qual Life Outcomes 5: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1969) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Academic Press: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Denters MJ, Deutekom M, Essink-Bot ML, Bossuyt PM, Fockens P, Dekker E (2013) FIT false-positives in colorectal cancer screening experience psychological distress up to 6 weeks after colonoscopy. Support Care Cancer 21: 2809–2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafslund B (2000) Mammography and the experience of pain and anxiety. Radiography 6: 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Holme O, Bretthauer M, Fretheim A, Odgaard-Jensen J, Hoff G (2013) Flexible sigmoidoscopy versus faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9: CD009259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holme O, Loberg M, Kalager M, Bretthauer M, Hernan MA, Aas E, Eide TJ, Skovlund E, Schneede J, Tveit KM, Hoff G (2014) Effect of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 312: 606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodl MM, Powell AA, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Bangerter AK, Partin MR (2010) Mental health, frequency of healthcare visits, and colorectal cancer screening. Med Care 48: 934–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing SS, Bogart A, Chubak J, Fuller S, Green BB (2014) Psychological distress after a positive fecal occult blood test result among members of an integrated healthcare delivery system. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 23: 154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loge JH, Kaasa S (1998) Short form 36 (SF-36) health survey: normative data from the general Norwegian population. Scand J Soc Med 26: 250–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loge JH, Kaasa S, Hjermstad MJ, Kvien TK (1998) Translation and performance of the Norwegian SF-36 Health Survey in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. I. Data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability, and construct validity. J Clin Epidemiol 51: 1069–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mccaffery KJ, Barratt AL (2004) Assessing psychosocial/quality of life outcomes in screening: how do we do it better? J Epidemiol Community Health 58: 968–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles A, Wardle J (2006) Adverse psychological outcomes in colorectal cancer screening: does health anxiety play a role? Behav Res Ther 44: 1117–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niv Y, Bogolavski I, Ilani S, Avni I, Gal E, Vilkin A, Levi Z (2012) Impact of colonoscopy on quality of life. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 24: 781–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW (2003) Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 41: 582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'connor M, Gallagher P, Waller J, Martin CM, O'leary JJ, Sharp L (2015) Adverse psychological outcomes following colposcopy and related procedures: a systematic review. BJOG 123: 24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson I, Mykletun A, Dahl AA (2005) The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Rating Scale: a cross-sectional study of psychometrics and case finding abilities in general practice. BMC Psychiatry 5: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Robinson MH, Scholefield JH, Hardcastle JD (2002) Psychiatric morbidity and screening for colorectal cancer. J Med Screen 9: 7–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzo E, Pezzoli A, Stockbrugger R, Bracci E, Vagnoni E, Gullini S (2011) Screenee perception and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer screening: a review. Value Health 14: 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pornet C, Dejardin O, Morlais F, Bouvier V, Launoy G (2010) Socioeconomic determinants for compliance to colorectal cancer screening. A multilevel analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 64: 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhan MA, Frey M, Buchi S, Schunemann HJ (2008) The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 6: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb KA, Lo SH, Power E, Kralj-Hans I, Edwards R, Vance M, Von Wagner C, Atkin W, Wardle J (2013) Patient-reported outcomes following flexible sigmoidoscopy screening for colorectal cancer in a demonstration screening programme in the UK. J Med Screen 19: 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb KA, Miles A, Wardle J (2004) Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with perceived risk for colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13: 366–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salz T, Richman AR, Brewer NT (2010) Meta-analyses of the effect of false-positive mammograms on generic and specific psychosocial outcomes. Psychooncology 19: 1026–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taupin D, Chambers SL, Corbett M, Shadbolt B (2006) Colonoscopic screening for colorectal cancer improves quality of life measures: a population-based screening study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KL, Shelby R, Gelmann E, Mcguire C (2004) Quality of life and trial adherence among participants in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 1083–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiis-Evensen E, Hoff GS, Sauar J, Vatn MH (2000) Patient tolerance of colonoscopy without sedation during screening examination for colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 52: 606–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiis-Evensen E, Wilhelmsen I, Hoff GS, Blomhoff S, Sauar J (1999) The psychologic effect of attending a screening program for colorectal polyps. Scand J Gastroenterol 34: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65: 87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Jaarsveld CH, Miles A, Edwards R, Wardle J (2006) Marriage and cancer prevention: does marital status and inviting both spouses together influence colorectal cancer screening participation? J Med Screen 13: 172–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Taylor T, Sutton S, Atkin W (1999) Does publicity about cancer screening raise fear of cancer? Randomised trial of the psychological effect of information about cancer screening. BMJ 319: 1037–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Williamson S, Sutton S, Biran A, Mccaffery K, Cuzick J, Atkin W (2003) Psychological impact of colorectal cancer screening. Health Psychol 22: 54–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 34: 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Kosinski M (2001) Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A Manual For Users Of Version 1. Quality Metric. Inc: Lincoln, RI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67: 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]