Abstract

Background

There is a paucity of data on the distribution of disease severity. In this study, we estimated disease severity distributions in South Korea using two EQ-5D-3L population surveys.

Methods

A total of 110 health states for 35 diseases with 2–5 severity levels (e.g., mild, moderate, severe) were included in this study. A general population of 360 participants from the areas surrounding Seoul and Gyunggi evaluated these health states using EQ-5D-3L via face-to-face interviews and a paper questionnaire. The EQ-5D indices were used to measure the severity levels of health states and used as the cutoff points for the disease severity distributions. Finally, these cutoff points were applied to disease prevalence data with EQ-5D-3L, which were obtained from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHNES) and Korean Community Health Survey, in order to estimate the disease severity distributions.

Results

The severity distributions of 8 diseases were estimated, including asthma, angina, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major depressive disorder, musculoskeletal problems in the legs, anemia, and allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis. For example, the EQ-5D indices for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity were 0.929, 0.742, and 0.620, and the cut-off points were 0.835 (between mild and moderate) and 0.681 (between moderate and severe). Using these cutoff points, the distributions of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity were 66.5 % (mild), 23.3 % (moderate), and 10.1 % (severe) according to KNHNES.

Conclusions

The estimated severity distributions in this study can be used as a valid calculation of the disease burden in the general population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2904-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Disease severity, Prevalence, EQ-5D

Background

The disability-adjusted life year (DALY) is a summary measure of overall disease burden and is expressed in terms of the number of years lost due to poor health, disability, or early death [1]. DALY has 2 components: years of life lost (YLLs) and years lived with disability (YLDs). This measure was first developed in 1990 as an approach for comparing the overall health and life expectancies of different countries [2]. Recently, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study group adopted a prevalence-based approach rather than an incidence-based approach [3]. Using both approaches, the YLL component is calculated using the same principle, which takes advantage of the number of deaths and standard life expectancy at age of death in years. However, when determining the YLD component, there are some differences between the 2 approaches in terms of disease duration, disability weight, and comorbidity [4]. Using the prevalence-based approach, disease duration is not directly considered and the disability weights are applied to the disease sequelae rather than the disease itself. In addition, it is easier to consider comorbidity using the prevalence-based approach than the incidence-based approach.

Notably, the prevalence-based approach uses big changes related to disability weight. In fact, after the development of DALYs, there have been some debates on the measurement of health loss, the use of person trade-offs, disability weights of whose perspectives, and the universality of disability weights [5]. In their 2010 study, the GBD group conducted international surveys on the general public using paired comparisons to estimate disability weights [6]. These changes make it easier to calculate DALYs, but this approach requires more data that were not needed when using the incidence-based approach, such as data about severity distribution [7]. Using the prevalence-based approach, the GBD group attempted to consider sequelae severity and briefly described the health state and sequelae severity [6]. In order to apply data on severity distributions and calculate DALYs, the GBD group asked a convenient sample of participants to evaluate SF-12v2 [8] for a hypothetical person, who was depicted as living with a certain health state from among 60 possible health states [9]. The GBD group then used population survey data from the United States and Australia to estimate marginal severity distributions.

They adapted this method because data on severity distributions are often scarce. However, applying the data on severity distributions from one country to another would impose limitations due to differences in race, economic factors, and healthcare system accessibility [10, 11]. In South Korea, two population surveys are available, the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHNES) and Korean Community Health Survey (KCHS), which have prevalence data and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) data using EQ-5D-3L [12]. Therefore, disease severity distributions could be determined from the KNHNES and KCHS modifying the method used in the GBD study. In our current study, we estimated disease severity distributions in the Korean general population using two EQ-5D-3L population surveys and health state valuation survey data.

Methods

Study participants

A general population of 360 adults (≥19 years) from the areas surrounding Seoul and Gyunggi participated in this study. The study participants were recruited and stratified according to age, sex, and education using data from the 2010 Census of Korea. The sample size was determined by allocating 30 participants to each health state group (12 health state groups).

Ethical considerations

This survey was conducted by a commercial survey company, who used face-to-face interviews and paper questionnaires after obtaining informed consent. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Asan Medical Center (S2014-1677-0002).

Health state valuation survey procedure and health states

First, sociodemographic characteristics were determined, such as sex, age group, region, and education level. Second, each study participant described their own health states using EQ-5D-3L to adapt to the instrument. Lastly, the study participants were asked to complete EQ-5D-3L for 9 or 10 hypothetical people, as described by the lay descriptions of health states in the order of good health states.

In total, 110 health states of 35 diseases with 2–5 severity levels (e.g. mild, moderate, and severe) were included in this study. Those health states mainly originated from 220 health states, which were described in the 2010 GBD study [6]. Each health state was depicted in terms of the lay descriptions, which described the status of each health state in terms of several health aspects. Because the lay descriptions were originally developed in English, MO first translated these descriptions, which were rechecked by MWJ. In addition, 4 diseases—allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis, annoyance, sleep disturbance, and cognitive impairment in children—were included in this study, because of local national burden of disease study for environmental diseases. The health states of additional 4 diseases were drafted by 2 authors (MO and MWJ) after referencing the existing lay descriptions reported by a previous study [6]. These 110 health states were divided into 12 groups, which were composed of 9–10 health states. Thirty participants were allocated to each health state group, therefore, each health state had 30 EQ-5D-3L responses. Exceptionally, the 3 health states related to anemia included 2 groups, so each health state of anemia had 60 EQ-5D-3L responses. We considered that at least 30 EQ-5D-3L responses using mean as a representative value would make parametric statistical tests possible. Table 2 lists the diseases and severity levels.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the EQ-5D-3L index for diseases by severity level

| No | Disease | Severity level | Response number | Mean | SD | Cut-off |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Infectious disease | Acute episode, mild | 30 | 0.934 | 0.068 | - |

| Acute episode, moderate | 30 | 0.802 | 0.099 | 0.868 | ||

| Acute episode, severe | 30 | 0.521 | 0.236 | 0.661 | ||

| 2 | Diarrhoea | Mild | 30 | 0.753 | 0.168 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.644 | 0.203 | 0.699 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.353 | 0.287 | 0.498 | ||

| 3 | Angina pectoris | Mild | 30 | 0.687 | 0.372 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.663 | 0.318 | 0.675 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.506 | 0.324 | 0.585 | ||

| 4 | Heart failure | Mild | 30 | 0.793 | 0.184 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.688 | 0.236 | 0.741 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.478 | 0.206 | 0.583 | ||

| 5 | Stroke | Long-term consequences, mild | 30 | 0.567 | 0.276 | - |

| Long-term consequences, moderate | 30 | 0.491 | 0.287 | 0.529 | ||

| Long-term consequences, moderate plus cognition problems | 30 | 0.311 | 0.348 | 0.401 | ||

| Long-term consequences, severe | 30 | −0.035 | 0.197 | 0.138 | ||

| Long-term consequences, severe plus cognition problems | 30 | −0.092 | 0.139 | −0.064 | ||

| 6 | Asthma | Controlled | 30 | 0.956 | 0.072 | - |

| Partially controlled | 30 | 0.849 | 0.139 | 0.902 | ||

| Uncontrolled | 30 | 0.717 | 0.228 | 0.783 | ||

| 7 | COPD & other respiratory problems | Mild | 30 | 0.929 | 0.108 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.742 | 0.191 | 0.835 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.620 | 0.245 | 0.681 | ||

| 8 | Dementia | Mild | 30 | 0.840 | 0.175 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.648 | 0.223 | 0.744 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.181 | 0.407 | 0.415 | ||

| 9 | Multiple sclerosis | Mild | 30 | 0.785 | 0.153 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.648 | 0.197 | 0.717 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.556 | 0.266 | 0.602 | ||

| 10 | Epilepsy | Treated, seizure free | 30 | 0.686 | 0.207 | - |

| Treated, with recent seizure | 30 | 0.545 | 0.225 | 0.615 | ||

| Untreated | 30 | 0.542 | 0.258 | 0.544 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.345 | 0.303 | 0.443 | ||

| 11 | Parkinson’s disease | Mild | 30 | 0.849 | 0.127 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.686 | 0.191 | 0.767 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.344 | 0.333 | 0.515 | ||

| 12 | Alcohol use disorder | Mild | 30 | 0.755 | 0.220 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.730 | 0.207 | 0.743 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.494 | 0.247 | 0.612 | ||

| 13 | Fetal alcohol syndrome | Mild | 30 | 0.850 | 0.136 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.731 | 0.135 | 0.79 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.426 | 0.256 | 0.579 | ||

| 14 | Anxiety disorder | Mild | 30 | 0.927 | 0.080 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.835 | 0.117 | 0.881 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.612 | 0.282 | 0.723 | ||

| 15 | Major depressive disorder | Mild | 30 | 0.813 | 0.157 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.436 | 0.345 | 0.624 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.159 | 0.366 | 0.298 | ||

| 16 | Intellectual disability | Mild | 30 | 0.662 | 0.311 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.685 | 0.215 | 0.673 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.444 | 0.291 | 0.564 | ||

| Profound | 30 | 0.383 | 0.286 | 0.414 | ||

| 17 | Hearing loss | Mild | 30 | 0.877 | 0.167 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.720 | 0.204 | 0.799 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.710 | 0.170 | 0.715 | ||

| Profound | 30 | 0.528 | 0.206 | 0.619 | ||

| Complete | 30 | 0.366 | 0.312 | 0.447 | ||

| 18 | Hearing loss with ringing | Mild | 30 | 0.675 | 0.319 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.635 | 0.248 | 0.655 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.528 | 0.317 | 0.581 | ||

| Profound | 30 | 0.454 | 0.282 | 0.491 | ||

| Complete | 30 | 0.368 | 0.287 | 0.411 | ||

| 19 | Distant vision | Mild impairment | 30 | 0.949 | 0.109 | - |

| Moderate impairment | 30 | 0.719 | 0.199 | 0.834 | ||

| Severe impairment | 30 | 0.429 | 0.333 | 0.574 | ||

| Blindness | 30 | 0.221 | 0.296 | 0.325 | ||

| 20 | Low back pain | Acute without leg pain | 30 | 0.446 | 0.363 | - |

| Acute with leg pain | 30 | 0.308 | 0.357 | 0.377 | ||

| Chronic without leg pain | 30 | 0.342 | 0.351 | 0.325 | ||

| Chronic with leg pain | 30 | 0.188 | 0.272 | 0.265 | ||

| 21 | Neck pain | Acute mild | 30 | 0.694 | 0.169 | - |

| Acute severe | 30 | 0.504 | 0.28 | 0.599 | ||

| Chronic mild | 30 | 0.544 | 0.209 | 0.524 | ||

| Chronic severe | 30 | 0.361 | 0.323 | 0.453 | ||

| 22 | Musculoskeletal problems: leg | Mild | 30 | 0.786 | 0.068 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.726 | 0.057 | 0.756 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.539 | 0.185 | 0.633 | ||

| 23 | Musculoskeletal problems: arms | Mild | 30 | 0.438 | 0.354 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.317 | 0.320 | 0.377 | ||

| 24 | Musculoskeletal problems: generalised | Moderate | 30 | 0.360 | 0.314 | - |

| Severe | 30 | 0.111 | 0.307 | 0.235 | ||

| 25 | Abdominopelvic problem | Mild | 30 | 0.882 | 0.063 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.699 | 0.156 | 0.791 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.238 | 0.250 | 0.469 | ||

| 26 | Disfigurement | Level 1 | 30 | 0.866 | 0.093 | - |

| Level 2 | 30 | 0.736 | 0.186 | 0.801 | ||

| Level 3 | 30 | 0.662 | 0.26 | 0.699 | ||

| 27 | Disfigurement: with itch or pain | Level 1 | 30 | 0.721 | 0.183 | - |

| Level 2 | 30 | 0.551 | 0.255 | 0.636 | ||

| Level 3 | 30 | 0.145 | 0.272 | 0.348 | ||

| 28 | Motor impairment | Mild | 30 | 0.817 | 0.151 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.648 | 0.151 | 0.733 | ||

| Severe | 30 | 0.129 | 0.330 | 0.389 | ||

| 29 | Motor plus cognitive impairment | Mild | 30 | 0.622 | 0.236 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.394 | 0.335 | 0.508 | ||

| Severe | 30 | −0.004 | 0.237 | 0.195 | ||

| 30 | Traumatic brain injury | long-term consequences, minor with or without treatment | 30 | 0.513 | 0.254 | - |

| long-term consequences, moderate with or without treatment | 30 | 0.161 | 0.279 | 0.337 | ||

| long-term consequences, severe with or without treatment | 30 | −0.001 | 0.319 | 0.080 | ||

| 31 | Anemia | Mild | 60 | 0.802 | 0.287 | - |

| Moderate | 60 | 0.596 | 0.313 | 0.699 | ||

| Severe | 60 | 0.416 | 0.335 | 0.506 | ||

| 32 | Allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis | Mild | 30 | 0.694 | 0.288 | - |

| Moderate | 30 | 0.645 | 0.269 | 0.670 | ||

| 33 | Annoyance | Mild | 30 | 0.805 | 0.264 | - |

| Severe | 30 | 0.676 | 0.305 | 0.740 | ||

| 34 | Sleep disturbance | Mild | 30 | 0.894 | 0.111 | - |

| Severe | 30 | 0.807 | 0.208 | 0.851 | ||

| 35 | Cognitive impairment in children | Mild | 30 | 0.838 | 0.258 | - |

| Severe | 30 | 0.816 | 0.181 | 0.827 |

SD standard deviation, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

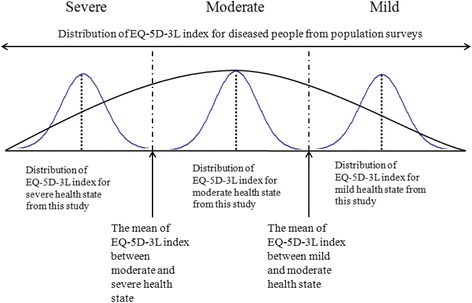

Analysis

Descriptive analyses of the basic characteristics of the study participants were first conducted. Then, the severity distributions were estimated using survey data obtained by this study and prior population survey data. Figure 1 shows the approach for estimating the severity distributions of the health states in this study. The EQ-5D-3L responses from each health state were transformed to the EQ-5D-3L index using the Korean EQ-5D-3L value set [13]. We used EQ-5D-3L rather than SF-12v2 because the KNHNES and KCHS adapted EQ-5D-3L to measure HRQoL. KNHNES and KCHS report different self-reported prevalence data by year. The cutoff points for the severity distributions of each disease were determined according to the averages of the mean values of the EQ-5D-3L index for the severity levels of the health states. Finally, these cutoff points were applied to the disease prevalence data from KNHNES and KCHS in order to estimate the disease severity distributions. We used pooled data from KNHNES (obtained between 2005 and 2012) and KCHS (2008–2012), respectively. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.0 software.

Fig. 1.

Approach used in this study to estimate disease severity distribution

Results

The basic characteristics and self-perceived HRQoL values of the study participants are listed in Table 1. In total, 50.6 % of the study participants (182 participants) were female. Participants in their 40s and residents of Gyunggi were the largest groups. These characteristics are similar to those reported for the general public in Seoul, Inchon, and Gyunggi. The mean EQ-5D index was 0.971 (standard deviation 0.08; median 1.000).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study participants

| Number | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 182 | 50.6 |

| Male | 178 | 49.4 | |

| Age group (years) | 19–29 | 67 | 18.6 |

| 30–39 | 73 | 20.3 | |

| 40–49 | 81 | 22.5 | |

| 50–59 | 70 | 19.4 | |

| 60- | 69 | 19.2 | |

| Region | Seoul | 148 | 41.1 |

| Incheon | 41 | 11.4 | |

| Gyunggi | 171 | 47.5 | |

| Education level (years) | −8 | 6 | 1.7 |

| 9–11 | 33 | 9.2 | |

| 12–15 | 224 | 62.2 | |

| 16- | 97 | 26.9 | |

| Mean (standard deviation) | |||

| Self perceived health related quality of life (EQ-5D-3L index) | 0.971 (0.08) | ||

Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations of the EQ-5D-3L indices according to the severity levels of 35 diseases. The raw survey data related EQ-5D-3L indices are available in the Additional file 1. The cutoff points were also calculated using the averages of the mean values of the EQ-5D-3L index for the severity levels of the health states. In the case of asthma, the EQ-5D-3L indices according to severity level were 0.956 (controlled), 0.849 (partially controlled), and 0.717 (uncontrolled). The cutoff points were 0.902 (between controlled and partially controlled) and 0.783 (between partially controlled and uncontrolled).

Some health states had negative mean values for their EQ-5D-3L indices. For example, the mean values of the EQ-5D-3L indices for “stroke: long-term consequences, severe” and “stroke: long-term consequences, severe plus cognition problems” were −0.035 and −0.092, respectively. Consequently, the cutoff point between “stroke: long-term consequences, severe” and “stroke: long-term consequences, severe plus cognition problems” was also negative at −0.064. However, the other cutoff values were all positive.

The severity distributions for 8 diseases were estimated using these cutoff values: asthma, angina, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), major depressive disorder, musculoskeletal problem in legs, anemia, and allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis (Table 3). The severity distributions of the other diseases, such as dementia and epilepsy, could not be estimated because the participants who had these diseases (such as dementia or epilepsy) did not have an EQ −5D profile in both KNHNES and KCHS. Overall, the proportion of participants with mild disease severity was larger than the proportion of moderate or severe disease severity for each disease. For example, the proportions of “stroke: long-term consequences, mild” were 86.4 % (KNHNES) and 81.0 % (KCHS), whereas those of “stroke: long-term consequences, severe” were only 1.9 % (KNHNES) and 5.0 % (KCHS). In the case of major depressive disorder, the distributions of severity were 88.8 % (mild), 9.8 % (moderate), and 1.5 % (severe) according to KNHNES. However, the proportions of severe cases with asthma, COPD, and musculoskeletal problems in the legs were >10 %. In particular, the severity distributions for asthma were 52.4 % (controlled), 14.4 % (partially controlled), and 33.2 % (uncontrolled) according to KCHS.

Table 3.

Estimated disease severity distributions

| No | Disease | Severity level | KNHNES | KCHS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Year | % | Year | |||

| 3 | Angina pectoris | Mild | 87.6 | 2005–2012 | 88.2 | 2008–2012 |

| Moderate | 3.1 | 2.1 | ||||

| Severe | 9.3 | 9.7 | ||||

| 5 | Stroke | Long-term consequences, mild | 86.4 | 2005–2012 | 81.0 | 2008–2012 |

| Long-term consequences, moderate | 4.9 | 5.4 | ||||

| Long-term consequences, moderate plus cognition problems | 6.5 | 6.0 | ||||

| Long-term consequences, severe | 1.9 | 5.0 | ||||

| Long-term consequences, severe plus cognition problems | 0.2 | 2.6 | ||||

| 6 | Asthma | Controlled | 53.9 | 2005–2012 | 52.4 | 2008–2012 |

| Partially controlled | 17.9 | 14.4 | ||||

| Uncontrolled | 28.2 | 33.2 | ||||

| 7 | COPD & other respiratory problems | Mild | 66.5 | 2005–2012 | ||

| Moderate | 23.3 | |||||

| Severe | 10.1 | |||||

| 15 | Major depressive disorder | Mild | 88.8 | 2007–2012 | 86.1 | 2009–2012 |

| Moderate | 9.8 | 10.8 | ||||

| Severe | 1.5 | 3.1 | ||||

| 20 | Low back pain | Acute without leg pain | 97.7 | 2008 | ||

| Acute with leg pain | 0.2 | |||||

| Chronic without leg pain | 0.3 | |||||

| Chronic with leg pain | 1.7 | |||||

| 22 | Musculoskeletal problems: leg | Mild | 74.5 | 2005–2012 | 71.2 | 2008 |

| Moderate | 14.3 | 17.0 | ||||

| Severe | 11.2 | 11.7 | ||||

| 31 | Anemia | Mild | 91.9 | 2005–2009 | 90.4 | 2008,2012 |

| Moderate | 6.1 | 6.9 | ||||

| Severe | 2.1 | 2.7 | ||||

| 32 | Allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis | Mild | 97.9 | 2005–2009 | 98.0 | 2008–2012 |

| Moderate | 2.1 | 2.0 | ||||

KNHNES Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, KCHS Korean Community Health Survey, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Discussion

We have estimated the severity distributions of 8 diseases (asthma, angina, stroke, COPD, major depressive disorder, musculoskeletal problem in legs, anemia, and allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis) using EQ-5D-3L. We performed face-to-face interviews, in which the survey participants completed the EQ-5D-3L for a hypothetical person as depicted by the lay descriptions explaining the health states of diseases. The EQ-5D-3L index was calculated for each health state using survey data obtained by this study, and the cutoff points for the severity distributions of each disease were determined according to the averages of the means of the EQ-5D-3L index for the severity levels of the health states. These cutoff points were applied to disease prevalence data obtained from population surveys performed at the national level (KNHNES and KCHS), and the severity distributions for each disease were estimated.

In terms of methodology, this study approach is similar to the indirect elicitation methods used to generate HRQoL weights [14]. The generic preference-based instruments such as EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index are generally used to evaluate status of health states developed to cover key aspects including physical and mental health in the indirect elicitation method. Although the measured aspects of health will differ depending on the instrument, it is easy to perform similar studies and comparability can be assured across diseases and countries. If there are prevalence data about HRQoL in other countries, it will be worth conducting similar studies in situations that lack data on disease severity distributions.

There is a paucity of data on disease severity distributions, although data on prevalence are relatively accessible [7]. Even though data on severity distributions are available, generalizability is limited in terms of the study designs used to collect data [15–17] and evaluate disease severity [18]. If there are national survey data on severity distributions in a certain country [19], the applicability of that data to other countries will be restricted due to differences in race, socio-demographics, and healthcare system accessibility. When collecting epidemiologic data, including prevalence and incidence, data on severity distributions are also needed to fundamentally solve this problem.

In our present study, we used 2 different population survey data sets (KNHNES and KCHS) to estimate the severity distributions. The estimated patterns for severity distribution using KNHNES and KCHS were quite similar. For example, in the case of angina pectoris, the severity distributions according to KNHNES were 87.6 % (mild), 3.1 % (moderate), and 9.3 % (severe). The severity distributions according to KCHS were 88.2 % (mild), 2.1 % (moderate), and 9.7 % (severe). These consistent results between the 2 population surveys data indicate that the reliability of this study is fair.

Overall, the proportion of participants with mild disease severity tended to be larger than moderate or severe disease severity for each disease included in this study. Because KNHNES and KCHS surveyed the general public, there is a possibility that the proportions of moderate or severe disease were underestimated. When compared with the results of other epidemiologic studies, some studies show similar results, whereas other studies demonstrate divergent results. For example, Lee et al reported that 51.8 % of their participants were stage 1 on the BODE index (reflecting the systemic nature of COPD), followed by 24.3 % at stage 2, 16.3 % at stage 3, and 7.6 % at stage 4 [18]. In this study, we estimated the severity distributions of COPD as follows: 66.5 % (mild), 23.3 % (moderate), and 10.1 % (severe). Furthermore, Cho et al suggested that the majority of individuals with low-back pain demonstrate low-intensity or disabling pain [17]. In this study, we also estimated that the proportion of cases with complicated, low-back pain was small.

According to a multinational survey on asthma, however, only 27 % of patients from South Korea reported having asthma that was well or completely controlled [20]. In our present study, we predicted that 53.9 and 52.4 % of people with asthma were in control of their disease according to KNHNES and KCHS data, respectively. These results could be due to limitations in the EQ-5D-3L used to evaluate asthma HRQoL. That is, EQ-5D-3L might not reflect all aspects of asthma, so further studies that use similar methods as this study, including disease-specific HRQoL instruments, will be needed to verify the reasons for the gap between reports.

This study has several limitations. First, we estimated the EQ-5D-3L indices and cutoff points for 35 diseases by severity, but the severity distributions were only determined for 8 diseases due to limitations in the population survey data. In KNHNES and KCHS, there are no prevalence-based data for undetermined diseases such as Parkinson’s diseases or sleep disturbance. However, if prevalence-based data with HRQoL are generated, we would be able to estimate the severity distributions of other diseases using the cutoff points from our analyses. Second, the survey participants were asked to complete EQ-5D-3L for hypothetical persons in the order of good health states. If our participants had completed the EQ-5D-3L for hypothetical people in the order of bad health states, different EQ-5D-3L indices might have been estimated. Third, when applying the cut-off points from the survey to the EQ-5D-3L indices of the KNHES and KCHS, we could not consider comorbidity in the KNHES and KCHS due to the limitation of data source. A person with a certain disease may have other diseases in the KNHES and KCHS, therefore, reported EQ-5D-3L indices in a certain disease may be influenced by concomitant diseases. Comparing a person without any comorbidity in a certain disease, the reported EQ-5D-3L indices in a certain disease would be underestimated and the proportions of severe cases would be overestimated.

Conclusions

Using EQ-5D-3L, our present study has provided the severity distributions of 8 diseases (asthma, angina, stroke, COPD, major depressive disorder, musculoskeletal problem in legs, anemia, and allergic rhinitis and conjunctivitis) in the Korean population. Using our approach, valid disease burden could be calculated in the future in South Korea and other countries using disease severity distributions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gallup Korea for help in conducting survey. The authors also are grateful to the participants of survey.

Funding

This study was funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) as “the Environmental Health Action Program (grant number: 2014001350001).”

Abbreviations

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DALYs

disability adjusted life years

- GBD

global burden of disease

- HRQoL

health related quality of life

- KCHS

Korean Community Health Survey

- KNHNES

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys

- YLDs

years lived with disability

- YLLs

years of life lost

Additional file

Availability of data and materials. (XLSX 204 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. MO, MWJ, YHG, and HJL participated in the acquisition of data and analyses of data. MO, MWJ, JL, and CSS contributed to the interpretation of data and provided statistical guidance. MO, MWJ, and CSS were involved in drafting the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Minsu Ock, Email: ohohoms@naver.com.

Min-Woo Jo, Email: mdjominwoo@gmail.com.

Young-hoon Gong, Email: drzero00@naver.com.

Hyeon-Jeong Lee, Email: trueprsc@hanmail.net.

Jiho Lee, Email: oemdoc@naver.com.

Chang Sun Sim, Phone: +82-52-250-8933, Email: zzz0202@naver.com.

References

- 1.Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(3):429–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349(9063):1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Ezzati M, Flaxman AD, Lim S, Lozano R, Michaud C, et al. GBD 2010: design, definitions, and metrics. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2063–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61899-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health . Ways and means: A report on methodology from the New Zealand burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors study, 2006–2016. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haagsma JA, Polinder S, Cassini A, Colzani E, Havelaar AH. Review of disability weight studies: comparison of methodological choices and values. Popul Health Metr. 2014;12:20. doi: 10.1186/s12963-014-0020-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salomon JA, Vos T, Hogan DR, Gagnon M, Naghavi M, Mokdad A, et al. Common values in assessing health outcomes from disease and injury: disability weights measurement study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2129–2143. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61680-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The SF-12®: An Even Shorter Health Survey. Version 2.0. http://www.sf-36.org/tools/sf12.shtml . Accessed 28 Jan 2016.

- 9.Supplement to: Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380: 2163-2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Lee YK, Nam HS, Chuang LH, Kim KY, Yang HK, Kwon IS. South Korean time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states: modeling with observed values for 101 health states. Value Health. 2009;12(8):1187–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitehead SJ, Ali S. Health outcomes in economic evaluation: the QALY and utilities. Br Med Bull. 2010;96:5–21. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.EQ-5D-3L. EuroQol. http://www.euroqol.org/eq-5d-products/eq-5d-3l.html. Accessed 28 Jan 2016.

- 13.Son KM, Cho NH, Lim SH, Kim HA. Prevalence and risk factor of neck pain in elderly Korean community residents. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(5):680–686. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.5.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DS, Lee JH, Lee KH, Lee MG. Prevalence and severity of atopic dermatitis in Jeju Island: a cross-sectional study of 4,028 Korean elementary schoolchildren by physical examination utilizing the three-item severity score. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92(5):472–474. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho NH, Jung YO, Lim SH, Chung CK, Kim HA. The prevalence and risk factors of low back pain in rural community residents of Korea. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37(24):2001–2010. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31825d1fa8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H, Kim S, Lim Y, Gwon H, Kim Y, Ahn JJ, et al. Nutritional status and disease severity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56(3):518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, Smith B, Kumar R, Pongracic J, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e9–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makino M, Tsuboi K, Dennerstein L. Prevalence of eating disorders: a comparison of Western and non-Western countries. MedGenMed. 2004;6(3):49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schena FP. Epidemiology of end-stage renal disease: International comparisons of renal replacement therapy. Kidney Int. 2000;57:S39–S45. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07407.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson PJ1, Salvi S, Lin J, Cho YJ, Eng P, Abdul Manap R, et al. Insights, attitudes and perceptions about asthma and its treatment: findings from a multinational survey of patients from 8 Asia-Pacific countries and Hong Kong. Respirology. 2013;18(6):957–967. doi: 10.1111/resp.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]