Abstract

“Legal highs” such as K2, which typically contain synthetic cannabinoids, are increasingly popular with adolescents around the world. We have limited knowledge concerning their toxicity or adverse effects and their mechanism of action is poorly understood. While synthetic cannabinoids have been linked to adverse cardiovascular effects, cases of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) associated with K2 use are exceedingly rare. We report a case of a 14-year-old boy who suffered an STEMI after smoking K2. To our knowledge, this is not only the youngest case of an STEMI associated with K2 use, but also the first case to be reported outside of the United States of America. Pediatricians worldwide must be aware of the clinical significance and potential harm associated with the use of synthetic cannabinoids, to better educate patients and their families regarding the dangers of using such “legal” substances.

Keywords: K2, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, synthetic cannabinoids

INTRODUCTION

While chest pain is a common complaint among pediatric patients, most presentations are noncardiac in origin.[1] Of those that have an underlying cardiac etiology, myocardial infarction (MI) remains exceedingly rare and is usually associated with anatomical congenital cardiovascular abnormalities.[1] Other associations include Kawasaki disease, familial hypercholesterolemia, cardiomyopathy, peri- or myocarditis, and cocaine abuse.[2] Though cannabis is recognized as a rare trigger for MI,[3,4] the role of synthetic cannabinoids in MI among adolescents is poorly defined.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 14-year-old Māori boy was presented to the emergency department with a 1-h history of sudden onset central chest pain and headache. There was no fever, nausea, palpitations, or shortness of breath. Personal and family histories for cardiovascular disease were negative. He was taking no regular medications and denied regular cannabis use. He admitted, however, to having smoked the synthetic cannabis product K2 for the first time, 4 h prior to the onset of symptoms. The examination was unremarkable except for a mild tachycardia of 96 beats/min and a blood pressure (BP) of 168/81 mmHg.

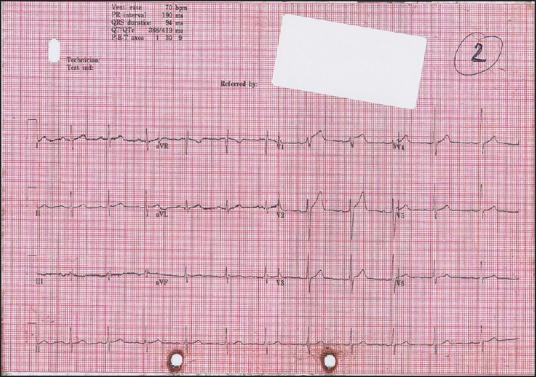

Electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated sinus tachycardia. Chest X-ray was unremarkable. His initial blood tests, including inflammatory markers, were unremarkable except for a raised troponin T (TnT) of 32 ng/L. He was treated with paracetamol and codeine, following which symptoms subsided, with heart rate and BP normalizing. He suffered further chest pain 4 h later. A repeat TnT showed a 50% rise to 48 ng/L, while a repeat ECG demonstrated concerning changes with ST-elevation in leads V1 and V2 [Figure 1]. A further ECG 1 h later showed improvement in the ST-elevation. Once again, his pain subsided with oral analgesia.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram 4 h post-presentation, with recurrence of chest pain showing ST-elevation in leads V1-V2

Over the next 48 h, the patient suffered two further episodes of chest pain. While observations and examination remained unremarkable throughout these episodes, TnT continued to rise, peaking at 383 ng/L on day 2 of admission, before returning to normal over a period of 7 days. Repeat ECGs, including those taken at the time of symptoms, normalized over the course of the admission, with no residual ST changes. All episodes of chest pain resolved with simple analgesia.

Despite denial of cannabis use, initial urine toxicology was positive for cannabinoids and opiates, but negative for amphetamine or benzodiazepines. The patient had been treated with codeine by the time of specimen collection. A further urine specimen collected 3 days later was negative for synthetic cannabinoid compounds. Subsequently, an exercise treadmill test (ETT) was completed with no chest pain or ST-segment changes, indicating that macrovascular disease would be highly unlikely. An echocardiogram, conducted on day 3 of admission, was also reported normal, with no evidence of pulmonary hypertension.

The symptoms and investigation results were consistent with a diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), with the most likely precipitating factor being the use of K2. In view of the symptoms resolving, the reassuring ETT and echocardiogram and normalizing TnT and serial ECGs, the regional cardiology team advised not to treat the patient with anti-platelets or anticoagulation. He was discharged after 7 days. At 1-year follow-up, he has remained asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

“Legal highs” such as K2 are products with mood-altering properties that are not prohibited by government legislation. They typically contain synthetic cannabinoids and are increasingly popular with adolescents, as they are easily available to purchase in person or via the internet.[5] Like delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the most biologically active ingredient in traditional cannabis,[6] synthetic cannabinoids act mainly as agonists to cannabinoid-1 receptors. However, unlike THC, which is a partial agonist, synthetic cannabinoids are full agonists, which may explain their increased potency and subsequent potential for more intense sympathomimetic effects.[7] While the full range of synthetic cannabinoid-related adverse health effects is unknown, the most common presentations include vomiting, agitation, and tachycardia.[7,8]

To our knowledge, there have been only four reported cases of patients presenting with STEMIs after smoking K2.[5,9] As in two of these cases, our patient tested positive for THC, suggesting concomitant cannabis use in the preceding weeks. While this complicates the association between K2 and MI, the time frame between the patients first ever episode of smoking K2 and onset of symptoms suggests K2 to be the most likely precipitant.

Routine urine drug immunoassays do not detect synthetic cannabinoids. In the previous cases of MI associated with K2,[5,9] urine testing for synthetic compounds was either not performed or negative. Additionally, as in our case, the substance smoked was not analyzed. Therefore, we do not know the full range of potentially harmful compounds within the sample of K2 smoked by our patient and we cannot be certain which compounds were responsible for his symptoms. The fact that no synthetic cannabinoids were detected in our patient's urine sample may be due to the time delay between the presentation and specimen collection, by which point the compounds may have been eliminated from the body.

Despite the growing evidence base for the association between K2 and MI in adolescents, there are no consensus management guidelines, as the physiology and pharmacology by which adolescents suffer MIs remains poorly understood. Limited evidence suggests that the mode of MI is through coronary vasospasm or increased myocardial oxygen demand rather than atheroma build-up.[3] Consequently, our patient was not prescribed anticoagulation. In previous cases, of the three patients that underwent angiography, all revealed normal coronary arteries.[5,9]

To our knowledge, this is not only the youngest case of an STEMI associated with K2 use, but also the first case to be reported outside of the United States of America. The use of these products is an increasingly worldwide phenomenon. The literature in this field is limited, and further research is needed to better understand synthetic cannabinoids and their cardiovascular effects, as consensus management guidelines for these cases remains elusive. Pediatricians worldwide must be aware of the clinical significance and potential harm associated with the use of synthetic cannabinoids, to better educate patients and their families regarding the dangers of using such “legal” substances.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge Dr. Leo Schep, Toxicologist, from the National Poisons Centre, University of Otago, New Zealand, for his valuable expertise during the management of the case, and his kind advice during the development of the report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lane JR, Ben-Shachar G. Myocardial infarction in healthy adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e938–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suryawanshi SP, Das B, Patnaik AN. Myocardial infarction in children: Two interesting cases. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;4:81–3. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.79633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mittleman MA, Lewis RA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Muller JE. Triggering myocardial infarction by marijuana. Circulation. 2001;103:2805–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kocabay G, Yildiz M, Duran NE, Ozkan M. Acute inferior myocardial infarction due to cannabis smoking in a young man. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2009;10:669–70. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32832bcfbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mir A, Obafemi A, Young A, Kane C. Myocardial infarction associated with use of the synthetic cannabinoid K2. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1622–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dewey WL. Cannabinoid pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1986;38:151–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyte CO, Jacob J, Monte AA, Al-Jumaan M, Bronstein AC, Heard KJ. A characterization of synthetic cannabinoid exposures reported to the National Poison Data System in 2010. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:435–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young AC, Schwarz E, Medina G, Obafemi A, Feng SY, Kane C, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with the synthetic cannabinoid, K9, with laboratory confirmation. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1320.e5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKeever RG, Vearrier D, Jacobs D, LaSala G, Okaneku J, Greenberg MI. K2-not the spice of life; synthetic cannabinoids and ST elevation myocardial infarction: A case report. J Med Toxicol. 2015;11:129–31. doi: 10.1007/s13181-014-0424-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]