Abstract

George Huntington described some families with choreiform movements in 1872 in the United States of America and since then many such families have been described in other parts of the world and works on the genetics of the disease have brought new vistas in the understanding of the disease. In 1958, Americo Negrette, a young Venezuelan physician observed similar subjects in the vicinity of Lake Maracaibo which was presented by his co-worker, Ramon Avilla Giron at New York in 1972 when United States of America had been commemorating the centenary year of Huntington's disease. Nancy Wexler, a psychoanalyst, whose mother had been suffering from the disease attended the meeting and organized a research team to Venezuela and they systematically studied more than 18,000 individuals in order to work out a common pedigree. They identified the genetic locus of the disease in the short arm of chromosome 4 and observed that it was a trinucleotide repeat disorder.

Keywords: Huntington, Wexler, Gusella, trinucleotide repeat length

George Huntington was born into a family of general practitioners in East Hampton, New York, USA in 1850. He had his medical training at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University and graduated in 1871. He started practicing medicine in his native place and soon reported cases of dementia and chorea in middle-aged persons, which ran in families, conforming to the autosomal dominant mode of transmission. He also reported a series of such cases examined by his father and grandfather in the past, worked on these cases, and studied their families in great detail; his father's correctional notes are evident in his original manuscript. The families he studied were ancestors of one Jeffrey Francis who emigrated from England in 1634, carrying the gene with him. He moved to Pomeroy, Ohio, USA in 1871 and when he was only 20 years of age, he presented his observations entitled, “On chorea” on the February 15, 1872 before Meigs and Mason Academy of Medicine at Middleport, Ohio, USA. It appeared in the “Medical and Surgical Reporter” of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA on April 13 in the same year [Figure 1].[1,2]

Figure 1.

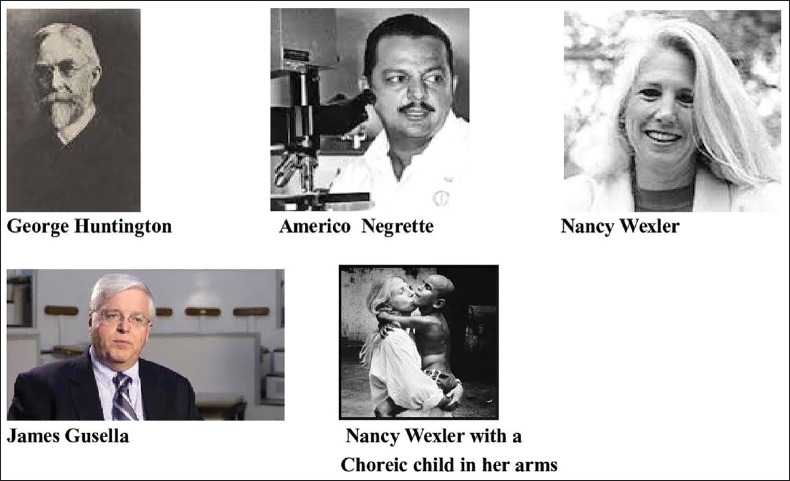

1. George Huntington. Source: www.commons.wikipedia.org 2. Americo Negrettte. Source: www.neurology.com 3. Nancy Wexler. Source: www.scientist.com 4. James Guella. Source: www.active.protomag.com 5. Nancy Wexler with a choreic child in her arms. Source: www.pinterest.com

He wrote,

“The name ‘chorea’ is given to the disease on account of the dancing propensities of those who are affected by it, and it is a very appropriate designation. The disease, as it is commonly seen, is by no means a dangerous or serious affection, however distressing it may be to the one suffering from it, or to his friends. Its most marked and characteristic feature is a clonic spasm affecting the voluntary muscles... The disease commonly begins by slight twitchings in the muscles of the face, which gradually increase in violence and variety. The eyelids are kept winking, the brows are corrugated, and then elevated, the nose is screwed first to the one side and then to the other, and the mouth is drawn in various directions, giving the patient the most ludicrous appearance imaginable. The upper extremities may be the first affected, or both simultaneously… As the disease progresses the mind becomes more or less impaired, in many amounting to insanity, while in others mind and body gradually fail until death relieves them of their suffering. When either or both the parents have shown manifestations of the disease, one or more of the offsprings invariably suffers from the condition... It never skips a generation to again manifest itself in another...”[2,3]

However, it is on record that before Huntington described the entity in 1872, Johan Christian Lund, a Norwegian physician, noted a high prevalence of dementia, along with jerky movements in subjects in the remote and secluded areas in Setesdalen, Sørlandet, Norway in 1860, and for that reason the disease is often referred to as “setesdal rykkja” in that country.[4] Even though previous workers had reported this condition, it was the lucidity and clarity of expression, which marked Huntington's description and that earned him the eponym “Huntington's disease” (HD), previously known as “Huntington's chorea.”

Ever since Huntington described the entity in great detail, the condition has been thoroughly studied, particularly in the last century, and it will perhaps be appropriate to examine the historical evolution in the understanding of this entity over the ages ever since he offered a comprehensive clinical account of the disease.

It is noteworthy that a disease presenting similarly had been known to many generations in families in colonial New England and was known as “magrums” or “megrims” by the local inhabitants. The victims of the disease were treated as despicable witches and were burnt to death publicly. They interpreted the uncontrollable involuntary movements as “a derisive pantomime of the sufferings of the Saviour during crucifixion” and the families were also believed to be cursed.[5] It is now widely believed that many of the victims in the infamous Salem Witch Trials that took place in Salem, Massachusetts, USA from 1692 to 1693 were in fact, sufferers of HD. Their choreic movements and odd behavior were perceived as possession by the devil and they were brutally executed. In all likelihood, the Puritans who emigrated from the UK to the USA in the latter part of the 17th century after the restoration of the monarchy in England in a ship named Mayflower carried the mutant gene and most unwittingly, transmitted the disease to the future generations in the USA.[1]

Before Huntington described the condition, physicians of earlier times such as Thelenius reported one such subject in 1816 while Ruspf brought to light one more patient in 1834. Charles Waters followed close on the heels and published his observations in Dunglison's “Practice of Medicine” in 1842 and this has been generally acknowledged as the first written account of the illness. This was later to be the subject for the thesis of Charles Gorman of Pennsylvania in 1848 and was reported again by Groving Lyon in “American Medical Times” in 1863.[1] Huntington himself wrote in his treatise, “Dufosse and Rufz refer to 429 cases; 130 occurring in boys and 299 in girls. Watson mentions a collection of 1,029 cases, out of whom 733 were females, giving a proportion of nearly 5 to 2. Dr. Watson also remarks upon the disease being most frequent among children of dark complexion, while the two authorities just alluded to, Dufosse and Rufz, give as their opinion that it is most frequent in children of light hair.”[2] The German literature reported cases described by Adolf Kussmaul and Carl Hermann Nothnagel in 1872.[5] Smith Jelliffe and Tilney took up the task of tracing the ancestry of the families and Vassie concluded the study in 1932. The latter found that all these patients could be traced to only six individuals who had migrated from the Anglican village of Bures, Suffolk in England, the UK to Boston Bay, Massachusetts, USA and one remarkable generation could be traced for 300 years through twelve generations and all of them expressed the disease. Some feel that the disease was imported to the USA from the UK by the wife of a young Englishman in 1630; the match was disapproved by the boy's family as the girl's father was choreic. Undaunted, this brave young man married the girl and they immigrated to the USA and transmitted the disease through their children that spread relentlessly throughout the USA. Many others could be traced to a family in Somerset in the UK who later settled in Tasmania, Australia.[1,4] Similarly, historians believe that the disease spread to South Africa by a Dutch immigrant named Elsje Cloetens who arrived there in 1652 and his descendants developed the disease with time. Alois Alzheimer, Pierre Marie, Jean Lhermitte, and Oskar Vogt among others, performed intensive autopsy study on the brains of these patients.[4]

The Maracaibo Story

In the mid-1950s, Americo Negrette, a young Venezuelan physician who graduated in 1949, chanced upon the town of San Luis near the Lake of Maracaibo where he was to spend 1 year in the national service. This percipient young physician observed with alacrity that some people had been behaving curiously with shakes, as if they were uncontrollably inebriated. The neighbors suggested that these strange people would soon be invalid to the extent that voluntary activities could not be performed easily and they would eventually die. The condition was known as “el mal de San Vito,” meaning “the inauspicious dance” among the local inhabitants.[6] Negrette, in his enthusiasm, took a detailed history, examined the subjects, and concluded that the problem was one of dementia and choreiform movements. He further observed, following the detailed family history, that the transmission of the disease could be traced back to the preceding generations and thus, it conformed to an autosomal dominant pattern and concluded with his extraordinary vision that he was in reality, dealing with cases of HD.[1] Okun and Thommi, his collaborators, wrote that when he presented his observations at the Venezuelan Sixth Congress of Medical Science in 1955, he was met with reluctance in the local scientific community and a passive ear from government authorities, and Moscovich et al., further wrote accounts of his life and works.[6,7] He left for posterity his remarkable treatise, “Chorea de Huntington. Maracaibo, Venezuela: University of Zulia 1958,” that has firmly found its pride of place in the history of medicine and his autobiography, “Ciudad de Fuego” contains a detailed account of how he identified the illness. The book contained 226 pages.[8] Later, he received formal training in neurology from the Institute for Clinical and Medical Research in Madrid, Spain and was appointed a professor of Clinical Neurology in the Department of Medicine at the University of Zulia and then, founding director of the Clinical Research Institute at the same university.[6]

In 1972, Ramon Ávila-Girón, a student and later, coworker with Negrette, carried with him the video recordings of these patients in order to present the problem in the HD Centenary Celebration, which was organized in New York, USA at that time. There was a unanimous agreement about the disease entity among the experts, testifying to the clinical acumen of these two young brilliant physicians. Girón's data were published in 1973 in a book edited by the celebrated expert on movement disorders from Montreal, Quebec, Canada by André Barbeau, et al. and it was Barbeau himself who visited Venezuela and confirmed the diagnosis.[9] This was the largest single population of HD in the world scattered over a cluster of villages along the coast of the lake Maracaibo. The study further showed that these Venezuelans were all descendants from one woman, Maria Concepcion Soto, who lived there in the early 18th century and who perhaps inherited the gene from a European sailor who in all likelihood was her putative father though others believe that the culprit was a Spanish sailor from Hamburg, Germany named Antonio Justo Doria, who lived during the 18th century and who travelled to Venezuela to buy dye for a German factory.[1] By 1994, the number of these patients in the villages of Barranquitas and Lagunetas near Lake Maracaibo reached an astronomical figure of about 300 who were afflicted with the disease and over 100 were at 50% risk of suffering at a later date and unfortunately 10 generations of subjects had been born by that time.

Nancy Wexler, a psychoanalyst from the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke, whose mother and grandfather were victims of HD, attended the meeting and got inspired to get to the core of the problem. Wexler's father, Milton, was a psychoanalyst and clinical psychologist and her mother was a geneticist. In 1968, her father started the Hereditary Diseases Foundation, which introduced Nancy to scientists such as geneticists and molecular biologists and these associations ignited her interest in basic neurosciences. She organized a trip to Barranquitas and Lagunetas in the vicinity of Lake Maracaibo in July 1979 and surveyed the area with Thomas Chase, an acknowledged authority on Parkinsonism and movement disorders of the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. The Venezuelan Collaborative Huntington's Disease Society was thus formed and Nancy Wexler was appointed as the executive director and the office of the Society was located at the National Institute of Health. The principal investigators were Sir Ernesto Bonilla from Zulia and Nancy Wexler herself. They were aided by other neurologists, geneticists, anthropologists, and historians with the assumption that a genetic disease could best be understood by isolating the gene that caused it. They conducted a 20-year-long survey in which they collected over 4,000 blood samples and documented 18,000 different individuals in order to work out a common pedigree.[1] For her work, Wexler was awarded among many notable honors, the Mary Woodard Lasker Award for Public Service, the Benjamin Franklin Medal in Life Science, and Honorary Doctorates from New York Medical College, the University of Michigan, Bard College, and Yale University. Currently, she is a Higgins Professor of Neuropsychology in the Departments of Neurology and Psychiatry of the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. Since 1986, presymptomatic and prenatal testing for HD has been available internationally and Wexler served as a director of the program that provided such facilities though she never wanted to know the results of the testing.[10] She once stated that, “The genetic test gives people a crystal ball to see the future: Will the city be free of bombs from now on or will a bomb crash into their home, killing them and jeopardizing their children?”[11] A team of geneticists led by James Gusella, from Harvard Medical School in the Massachusetts General Hospital identified by the method of linkage analysis that the genetic locus for the disease was in the short arm of chromosome 4 and a landmark paper, authored by 14 investigators, was published in the cerebrated journal, “Nature” in 1983.[12] In 1992, Anita Harding, from Queen Square, London, England, UK identified that the number of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeats had a direct relationship with the extent of the severity of the disease[1] and in 1993, the Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group could isolate the gene at the precise location at 4p 16.3 position. In 1996, a transgenic mouse model (the R6 line) was created that could be made to exhibit the clinical features of HD.[1] Finally, in the same year, the team of 58 workers of the Huntington's Collaborative Research Group published their work in the journal “Cell,” which identified that the gene huntingtin or interesting transcript (IT) 15 codes a protein that leads to the development of the disease.[13] And with that ended one of the most remarkable endeavors in order to grasp the genetic composition of a crippling neurological disorder.

Huntington moved to New York, USA in 1874 and apart from 2 years in North Carolina, USA, he spent the remainder of his life in the practice of medicine in Duchess County, New York, USA and retired in 1915. In New York, USA he joined a number of medical associations and worked in the Matteawan General Hospital. Similar to James Parkinson of the UK, he never held any academic or hospital position and did not contribute much to the medical literature expect for his initial description of chorea. His primary interest lay in his patients. He was a humorous and modest man who enjoyed hunting, fishing, sketching wildlife, and playing the flute and was particularly attentive toward his apparel. He was endowed with a keen intellect and he was a witty man. He was kind and conscientious in his medical practice and much loved by his patients. He often suffered from bouts of asthma but he continued his medical practice up to the age of 64 years. He died from pneumonia in 1916 at the age of 66 years in New York, USA.[1,14]

In his personal memoirs he wrote:

“Over fifty years ago, in riding with my father on his professional rounds, I saw my first case of ‘that disorder’, which was the way in which the natives always referred to the dreaded disease. It made a most enduring impression upon my boyish mind, an impression every detail of which I recall today, an impression which was the very first impulse to my choosing chorea as my virgin contribution to medical lore. We suddenly came upon two women, mother and daughter, both tall, thin, almost cadaverous, both bowing, twisting, grimacing. I stared in wonderment. What could it mean? My father paused to speak with them and we passed on. Then my medical instruction had its inception. From this point on, my interest in the disease has never wholly ceased.”[2]

Sir William Osler wrote,

“In the history of medicine there are few instances in which a disease has been more accurately, more graphically or more briefly described”. There is currently a trend to use the designation Huntington's disease rather than Huntington's chorea but the original title is still widely known, accepted and understood.”[3]

Finally, it is important to note that George Huntington should not be confused with George Sumner Huntington, who was a professor of comparative anatomy from the USA. They lived and worked at more or less the same period of time and both of them attended the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University![1,15]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bhattacharyya KB. Eminent Neuroscientists: Their Lives and Works. 1st ed. Kolkata: Academic Publishers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huntington G. On Chorea. Medical and Surgical Reporter. Philadelphia: SW Butler; 1872. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lo DC, Hughes RE. Neurobiology of Huntington's Disease: Applications to Drug Discovery. Vol. 1. CRC Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stien R. The history of the hereditary progressive chorea in Norway and Johan Christian Lund and his contribution to the understanding of this disease. In: Boucher M, Broussole E, editors. History of Neurology. Vol. 1. Lyon: Foundation Marcel Merieux; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pryse-Phillips W. Companion to Clinical Neurology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okun MS, Thommi N. Americo Negrette (1924-2003). Diagnosing Huntington Disease in Venezuela. Neurology. 2004;63:340–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000129827.16522.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moscovich M, Munhoz RP, Becker N, Barbosa ER, Espay AJ, Weiser R, et al. Américo Negrette and Huntington's disease. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69:711–3. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2011000500025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negrette A. Corea de Huntington. 2nd ed. Maracaibo: Talleres Graficos de la Universidad del Zulia; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wexler NS. The Tiresias complex: Huntington's disease as a paradigm of testing for late-onset disorders. FASEB J. 1992;6:2820–5. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.10.1386047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wexler NS, Conneally PM, Housman D, Gusella JF. A DNA polymorphism for Huntington's disease marks the future. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:20–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060010026009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avila-Girón R. Medical and social aspects of Huntington's chorea in the State of Zulia, Venezuela. In: Barbeau A, Chase TN, Paulson GW, editors. Advances in Neurology. Vol. 1. New York: Raven-Press; 1973. pp. 261–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gusella JF, Wexler NS, Conneally PM, Naylor SL, Anderson MA, Tanzi RE, et al. A polymorphic DNA marker genetically linked to Huntington's disease. Nature. 1983;306:234–8. doi: 10.1038/306234a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haymaker W, Schiller F. Founders of Neurology. Springfield: Charles C Thomas; 1970. pp. 305–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Weiden RM. George Huntington and George Sumner Huntington. A tale of two doctors. Hist Philos Life Sci. 1989;11:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]