Abstract

Cryptotia attributable to deficient posterior skin coverage frequently recurs. Because local flaps cover only the posterior aspects of the defective upper auricular cartilage and lack functional support to resist collapse of the helix, especially if severe helical cartilage anomalies are present, additional support is required to prevent the postoperative recurrence of this anomaly. The authors present cases of cryptotia treated using local flaps including a Z-plasty or formation of a trefoil flap with an additional cartilage wedge graft on the cephaloauricular sulcus to enhance projection of the helix. The combination of a graft with a local flap using a large Z-plasty or trefoil flap efficiently corrects the cryptotia, and is associated with minimal visible scarring and few complications, including recurrence.

Cryptotia, also called “pocket ear,” is an invagination of the superior portion of the auricle under the overlying temporal skin.1 It is one of the most common congenital auricular malformations in Asian populations.2 In Japan, the incidence of cryptotia is ∼1 in 400.1,3 The principles of its surgical treatment consist of constructing auriculotemporal sulcus, covering the skin deficiency in the upper and posterior auricle, and correcting the cartilage deformity. Numerous operative techniques have been described for treating cryptotia, including V-Y-plasty, Z-plasty, the use of local skin flaps, and placement of various combinations of flaps and skin grafts.1,2,4–6 Local flaps are cosmetically satisfactory, with minimal visible scarring and few complications, and many different types of local flap have been developed.4,5,7–9 Local flaps, however, cover only the posterior aspects of the defective upper auricular cartilage, and lack any functional support to prevent collapse of the helix. Because cryptotia is often accompanied by deformed helical cartilage with insufficient mechanical strength to maintain lateral projection, additional support is required to prevent recurrence of cryptotia because of the helical cartilage deformity. Recurrence can be prevented only if all of the principles of cryptotia surgery have been followed and several combined modalities have been attempted.5,10,11 Combined with a local flap, the placement of a cartilage wedge can provide structural support for the helical projection to prevent a recurrence.

Here, we present cases of cryptotia treated using local flaps, including a Z-plasty or formation of a trefoil flap with a cartilage wedge graft on the cephaloauricular sulcus, and discuss the outcomes in terms of creation of an auriculotemporal sulcus, provision of additional skin to cover once-embedded cartilage, minimization of donor site morbidity, and the prevention of recurrence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

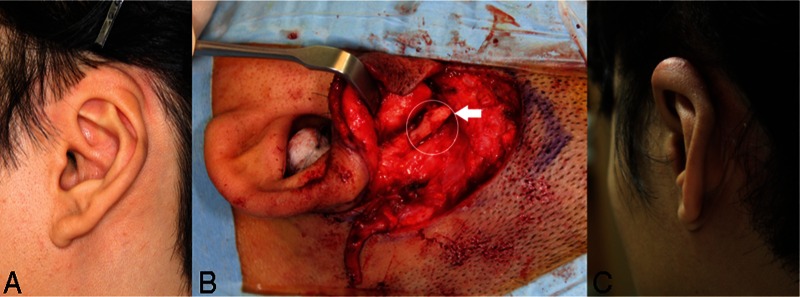

Between January 2011 and December 2014, 13 cryptotia deformities in 10 patients were corrected using large Z-plasty or trefoil flaps. Nine patients were treated by large Z-plasty and the remaining 4 via formation of trefoil flaps. Selection of operative technique was based on the surgeon's preference, with consideration of the extent of accompanying anomalies and the height of the hairline. The operation was performed under either general or local anesthesia, depending on patient age. Cryptotia surgery using a Z-plasty or trefoil flap followed the operative techniques of Yotsuyanagi et al12 and Adams et al.3 After elevating the flaps and exposing the posterior aspect of the scapha, the fibrous tissue and intrinsic transverse muscle causing contracture of the antihelix are dissected completely. When the antihelical cartilage is deformed, a 1.5 × 0.5-cm piece of ipsilateral conchal cartilage is harvested and fixed onto the superior portion of the cephaloauricular angle between the posterior aspect of the antihelical cartilage and periosteum of the mastoid bone to enhance projection of the helix (Fig. 1B). Finally, the flaps are transposed and sutured.

FIGURE 1.

A 32-year-old man with oblique muscle-type cryptotia of the left ear. A, Preoperative image. The superior portion of the helix was completely buried under the temporal skin and the inferior crus of the antihelix was acutely bent (arrow). B, Operative findings during large Z-plasty. A conchal cartilage graft was used to splint the auriculotemporal sulcus (arrow). C, Postoperative image taken 1 year later.

The surgical outcomes in terms of creation of an auriculocephalic sulcus and provision of additional skin to cover once-embedded cartilage, and the incidence of complications, including recurrence, were compared according to the surgical technique and the addition of a cartilage wedge graft on the cephaloauricular angle.

RESULTS

Patient age ranged from 5 to 32 years and all were followed for at least 1 year. No patient developed any severe complication, including postoperative infection or necrosis of the skin flap (Table 1). Both large Z-plasty and trefoil flap formation effectively provided the additional skin required to cover exposed cartilage and to create an auriculocephalic sulcus. One patient treated using a trefoil flap developed a dog-ear anomaly on the superior helix of the corrected ear; this was corrected successfully by secondary surgery. One patient treated with a large Z-plasty developed a hypertrophic scar and another patient treated using a trefoil flap grew hair on the transposed posterior auricular skin.

TABLE 1.

Complications According to Surgical Technique

| Conchal Cartilage Graft | Performed | Not Performed |

| Number of ears (patients) | 8 (6) | 5 (4) |

| Number of recurrences | 0 | 1 |

| Surgical flap technique (associated complications) | ||

| Z-plasty | 6 (1 hypertrophic scar) | 3 (none) |

| Trefoil flap | 2 (1 dog-ear deformity and 1 hair growth on flap) | 2 (1 recurrence) |

| Number of severe complications (including flap necrosis) | 0 | 0 |

To prevent recurrence and to maintain the sharply curved cephaloauricular angle, we added a conchal cartilage graft to the cephaloauricular sulcus in 8 of the 13 ears (Table 1). None of the patients who received a conchal cartilage wedge graft developed recurrent blunting of the cephaloauricular angle. The cryptotia recurred in one of the 4 patients (5 ears) who did not receive a conchal cartilage wedge graft on the cephaloauricular sulcus 6 months after treatment using a trefoil flap (patient 3). Secondary surgery featuring a large Z-plasty was successful without an added cartilage graft.

REPRESENTATIVE CASES

Patient 1

A 32-year-old man presented with oblique muscle-type cryptotia of the left ear. The superior portion of the helix was completely buried under the temporal skin and the inferior crus of the antihelix was acutely bent (Fig. 1A). The patient underwent cryptotia correction via a large Z-plasty under local anesthesia. To prevent cryptotia recurrence, cavum concha cartilage was harvested and sutured to the auriculotemporal sulcus (Fig. 1B). After 1 year, excellent results were achieved, to the patient's satisfaction. The resulting scar was inconspicuous (Fig. 1C).

Patient 2

A 25-year-old man presented with cryptotia of the transverse type. The upper portion of the auricle was buried beneath the skin, and the body and the superior crus of the antihelix were compressed together, causing underdevelopment of the helical cartilage (Fig. 2A). Surgical correction using trefoil flap construction was performed as described above, under local anesthesia. After skin incision, a lop ear deformity was noted. The lid-like downturn of the helical cartilage was excised and sutured to the upper surface of the underdeveloped helical cartilage, to enhance the helical outline. A conchal cartilage graft was splinted to the auriculotemporal sulcus to prevent cryptotia recurrence (Fig. 2B). At the 6-month follow-up, the results were satisfactory, and an enhanced helical contour was evident (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

A 25-year-old man with a transverse muscle-type cryptotia of the left ear. A, Preoperative image. The body and the superior crus of the antihelix were compressed together, causing underdevelopment of the helical cartilage. B, Operative findings during trefoil flap formation. An accompanying lop ear deformity was evident (arrow). C, Postoperative image taken 6 months later.

Patient 3

A 5-year-old boy presented with bilateral cryptotia (Fig. 3A). Surgical correction with construction of trefoil flaps was performed without the addition of a conchal cartilage graft under general anesthesia. After 9 months, blunting of the auriculotemporal sulcus was observed in the left auricle and the superior portion of the helix was buried under the scar of the temporal skin (Fig. 3B). Helical contouring of the right auricle was maintained. Secondary surgery, using a large Z-plasty to restore the auriculotemporal sulcus, was performed 1 year postoperatively. At the 9-month follow-up, satisfactory results were evident; the deepening of the auriculotemporal sulci of both ears was maintained (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

A 5-year-old boy with bilateral cryptotia. A, Preoperative image. The cryptotia was of the transverse muscle type in the left ear and of the oblique muscle type in the right ear. B, Recurrent cryptotia in the left ear 9 months after first surgery featuring construction of a trefoil flap. Blunting of the auriculotemporal sulcus was evident in the left auricle and the superior portion of the helix was buried under the scar of the temporal skin. C, Postoperative image taken 9 months after secondary surgery. The results were satisfactory; deep auriculotemporal sulci were maintained in both ears.

DISCUSSION

The primary purpose of operations seeking to correct cryptotia is the elimination of a skin deficiency on the posterior auricular surface, using upper and posterior auricular skin.2 It is accepted that local flap construction is better than skin grafting, and many types of such flaps have been described.4,8,13 Local flaps are cosmetically satisfactory, creating only minimal visible scarring, and are not associated with complications.12,14,15 A conspicuous scar, however, can develop when the flap is designed on the scalp or in the preauricular area. One advantage of the flap techniques used in this study is that the scar is invisible from both the anterior and lateral viewpoints.3,12 A large Z-plasty can scar the posterior surface of the auricle, but most scarring after creation of trefoil flaps is hidden in the temporal skin. Even in the patient who experienced recurrence, it was possible to render the scar invisible from the perspective of the anterior helix and preauricular regions. Both operative techniques efficiently minimize visible scarring and are easily reproducible. A trefoil flap is usually indicated in patients who do not need cartilage reconstruction because the risk of dehiscence is increased if extensive cartilage reconstruction is required. Alternatively, wide operative exposure to correct the cartilage deformity is available with a large Z-plasty. In the cases reviewed here, either operative technique yielded sufficient skin flap tissue to cover the posterior surface of the upper helical cartilage, and ensured the release of abnormal muscular and fibrous attachments. One limitation of the trefoil flap procedure is hair growth in the postauricular sulcus in patients with low hairlines.3 We encountered this complication in 1 adult. In addition, a “dog ear” developed in 1 patient was treated using construction of a trefoil flap. Dog-ear formation, however, can occur with most techniques using local flaps. It was easily corrected with minor secondary surgery and the hair on the posterior auricular surface was not of cosmetic concern to the patient. All patients treated using either operative technique were satisfied with their final results.

Early recurrence of cryptotia, attributable to deficient posterior skin coverage, is one of the major postoperative complications after cryptotia surgery. It is sometimes difficult to completely cover the posterior surface, especially if severe helical cartilage anomalies are evident.6,9,16 Although the use of these local flaps was successful for covering the posterior surface of the helical cartilage, the skin tension might be increased during the release, which potentially increases the risk of recurrence. Some authors have reported good results using isotonic saline injections during operations for 30 minutes and by pulling the ear 1 day before operation to lengthen and dissect the skin of the local flap because tissue expansion requires 2 separate surgical procedures.17,18 To prevent recurrence of the deformity, we reinforced the structural support for the helical projection with placement of a cartilage graft on the superior portion of the cephaloauricular angle, creating a “wedging” effect. In our series, no cryptotia recurred in any patient in whom a conchal cartilage graft was used as a wedge. It seems obvious that the addition of an appropriate surgical technique can prevent the reburial of the cartilage under the skin. Only 1 patient who did not receive a wedge graft experienced cryptotia recurrence, and this was corrected successfully using a large Z-plasty without addition of the cartilage graft, that is, another type of local flap. No skin graft was required and the scar visibility was minimal, even after secondary surgery. Therefore, fixation of the conchal cartilage graft on the cephaloauricular angle can ensure the structural support of the antihelix for the helical projection without blunting of the sulcus.

Because the deformation of the helical cartilage is a secondary abnormality often associated with cryptotia, it should be corrected concomitantly with cryptotia surgery if the deformity of the upper auricular portion is obvious.5,19 To correct an antihelical cartilage deformation, some authors advocate placement of a cartilage graft on the posterior or superior aspect of the antihelix.2,11,13 Hypoplastic helical cartilage deformities with accompanying lob ears were evident in 5 of 13 ears in this study. Concomitant use of the cartilage wedge graft and strut graft on the antihelix, as described in previous studies, can be helpful in the correction of the associated cartilage anomalies.5,10 Simultaneous construction of the auriculotemporal sulcus and correction of the cartilage deformity are recommended to prevent recurrence.5,10

Postoperatively, some bolster external fixations along the anterior scapha and posterior antihelix for 1 or 2 weeks can be applied to form an adhesion between the flap and cartilage.17 The recurrence in our cases developed after 9 months; therefore, periodic follow-up to 1 year postoperatively is recommended.

One of the limitations of this study was its relatively small sample size. Only 13 cases were described using multiple techniques; this study included patients treated with 2 different approaches for coverage, and some with and without cartilage grafts. Therefore, a statistical comparison was not possible. Our surgical outcome, however, could be considered effective because only 1 case of recurrent disease required a second surgery, which was successful. The success rates of the various surgical techniques for the correction of cryptotia should be investigated in further studies.

CONCLUSIONS

A cartilage wedge graft onto the superior portion of the cephaloauricular angle to enhance projection of the helix is useful at preventing the recurrence of cryptotia. In addition, the combination of the graft with a local flap using a large Z-plasty or trefoil flap formation efficiently corrects cryptotia, and is associated with minimal visible scarring and few complications, including recurrence.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paredes AA, Jr, Williams JK, Elsahy NI. Cryptotia: principles and management. Clin Plast Surg 2002; 29:317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho BC, Han KH. Surgical correction of cryptotia with V-Y advancement of a temporal triangular flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005; 115:1570–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams MT, Cushing S, Sie K. Cryptotia repair: a modern update to the trefoil flap. Arch Facial Plast Surg 2011; 13:355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang SO, Suh MW, Choi BY, et al. A new technique for correcting cryptotia: V-Y swing flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007; 120:437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SK, Yoon CM, Kim MH, et al. Considerations for the management of cryptotia based on the experience of 34 patients. Arch Plast Surg 2012; 39:601–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park S, Takushima M, Minegishi M. Reconstruction of cryptotia using a skin graft. Ann Plast Surg 1994; 32:441–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kajikawa A, Ueda K, Asai E, et al. A new surgical correction of cryptotia: a new flap design and switched double banner flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 123:897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh D, Sabbagh W, Gault D. Cryptotia correction: the post-auricular transposition flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2011; 64:1444–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakamoto Y, Nakajima H, Kishi K, et al. A new surgical correction of cryptotia with superior auricular myocutaneous flap. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010; 63:1995–2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park C. Upper auricular adhesion malformation: definition, classification, and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 123:1302–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YS. Correction of cryptotia with upper auricular deformity: double V-Y advancement flap and cartilage strut graft techniques. Ann Plast Surg 2013; 71:361–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yotsuyanagi T, Yamashita K, Shinmyo Y, et al. A new operative method of correcting cryptotia using large Z-plasty. Br J Plast Surg 2001; 54:20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onizuka T, Tokunaga S, Yamada K. A method for repair of cryptotia. Plast Reconstr Surg 1978; 62:734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu JH, Wu WH, Tan WQ. Surgical correction of cryptotia with the square flap method: a preliminary report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 2009; 43:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen W, Cui J, Chen J, et al. New technique for correcting mild types of cryptotia: elevate cavum conchae cartilage and suture to cranial periosteum. J Craniofac Surg 2012; 23:1830–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wesser DR. Repair of a cryptotic ear with a trefoil flap: case report. Plast Reconstr Surg 1972; 50:192–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qing Y, Cen Y, Yu R, et al. A new technique for correcting cryptotia: bolster external fixation method. J Craniofac Surg 2010; 21:1935–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uemura T, Matsumoto N, Tanabe T, et al. Surgical correction of cryptotia combined with intraoperative distention using isotonic saline injection and rotation flap method. J Craniofac Surg 2005; 16:473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park C, Yoo YS, Hong ST. An update on auricular reconstruction: three major auricular malformations of microtia, prominent ear and cryptotia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; 18:544–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]