Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Abstract

Prevalence of chronic hepatitis C (CH-C) infection in patients of Asian ancestry ranges between 1% and 20%. Interferon (IFN)- and ribavirin (RBV)-containing regimens for CH-C have a negative impact on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) during treatment.

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of IFN-free RBV-free sofosbuvir (SOF)-based regimens on PROs in CH-C patients of Asian ancestry.

In this observational retrospective study, the PRO data from 12 multicenter multinational phase 3 clinical trials (2012–2015, conducted in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand) of SOF-based regimens with and without IFN, ledipasvir (LDV), and/or RBV were used. At baseline, during treatment, and post-treatment, patients completed 4 validated PRO questionnaires (SF-36, CLDQ-HCV, FACIT-F, and WPAI:SHP). The resulting PROs in Asian patients were compared across the treatment regimens.

Of 4485 of the trials’ participants, 106 patients were of Asian ancestry (55.7% male, 69.8% treatment-naïve, 17.0% cirrhotic). In comparison with other patients, the Asian CH-C cohort was younger, had lower BMI, and lower rates of pre-treatment psychiatric comorbidities (anxiety, depression, sleep disorders) (all P < .05). At baseline, Asian patients also had lower SF-36 physical functioning scores (on average, by −5.6% on a normalized 0–100% PRO scale, P = .001). During treatment, Asian CH-C patients experienced a decline in their PRO scores while receiving IFN and/or RBV-containing regimens (up to −19.6%, P < .001). In contrast, patients receiving LDV/SOF experienced no PRO decrement and improvement of some PRO scores during treatment (+9.0% in general health of SF-36, P = .03). After achieving SVR-12, some of the PRO scores in Asian patients improved regardless of the regimen (up to +9.3%, P < .001). In multivariate analysis of Asian patients, the use of LDV/SOF was independently associated with higher PRO scores during and soon after the end of treatment (betas +15.0% to +29.3%, all P < .05). Other predictors of PRO impairment included depression, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cirrhosis.

The use of IFN- and RBV-free LDV/SOF regimens leads to PRO improvement in Asian patients with CH-C during treatment. Achieving SVR-12 results in improvement of PRO scores.

INTRODUCTION

The Asian population carries a high burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, although the actual numbers may vary depending on their country of origin. The highest HCV prevalence rate has been noted to be in Taiwan at 4.4%, though in some endemic areas in Japan, the prevalence rate has been cited to be as high as 20%.1 Despite a relatively lower prevalence rate (1%–1.9%), the absolute number of HCV-infected patients is still the greatest in China as compared with other Asian countries.1–3 In the United States, the prevalence of Hepatitis C in the Asians has been reported to be higher (4.2%) than the general US population rate of 1.3%.4–5

In addition, the genotype distribution in the Asian patients with HCV can also vary. In a recent study from Thailand, HCV genotype 3a was the most predominant (36.4%), followed by 1a (19.9%), 1b (12.6%), 3b (9.7%), and then 2a (0.5%). Furthermore, these investigators have also reported differences in HCV genotypes between the northern and the southern Thailand.6 In fact, HCV genotype 1 was found throughout Thailand, whereas genotype 3 was more common in the South and genotype 6 was more common in the North. Within Southeast Asia, high prevalence of HCV genotype 6 was reported in Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam, as well as in Hong Kong,1–3,6 whereas genotype 3 was more prevalent in Malaysia, and genotype 1 was more prevalent in the island nations of Singapore, Indonesia, and Philippines.6 However, in another study from the United States, the majority of Asian patients with HCV are found to have genotype 1 (1a, 20%; 1b, 35%; and 1 other, 7%).7 This is most likely because of a large proportion of Americans of Asian ancestry immigrating from South Korea and Taiwan where genotype 1 is more prevalent, whereas only 10% of Asian-Americans with HCV have genotype 6.7 This issue is especially important as genotypes are known to influence response to IFN-based therapy as well as response to sofosbuvir (SOF) and ribavirin (RBV).8–23

The new direct-acting antivirals (DAA)-based regimens with SOF and ledipasvir (LDV) have been reported to have high sustained virologic response (SVR) rates in genotype 1, 4, and 6.16–23 Furthermore, SOF/LDV is not only associated with very high response rates but also with improvement in patient-reported outcomes (PROs) during treatment and after achieving SVR.8–17 Although the impact of ethnicity to the outcomes of IFN-based CH-C treatment has been suggested,24 there is very little data regarding the effect of the new regimens on the PROs of HCV patients of Asian descent. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the effect of IFN-free RBV-free regimen with LDV/SOF on the PROs of CH-C patients of Asian ancestry enrolled in large clinical trials.

METHODS

The PRO data from 12 multicenter multinational phase 3 clinical trials of SOF-based regimens with and without IFN, LDV, and/or RBV conducted in 2012 to 2014 in the United States, Canada, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand were used.18–23 Only patients who reported to be of Asian ancestry were included. The participants were of all HCV genotypes, treatment-naive or experienced, without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, with or without coinfection with HIV. Patients’ medical history was collected at screening. Treatment-related adverse events were recorded by the trials’ investigators.

At baseline, during treatment, and post-treatment (up to 12 weeks after treatment cessation), while blinded to their current HCV RNA level, patients completed 4 validated PRO questionnaires (Short Form-36 [SF-36], Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-HCV [CLDQ-HCV], Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue [FACIT-F], and Work Productivity and Activity Index: Specific Health Problem [WPAI:SHP]). The resulting PROs were compared across treatment regimens.

Descriptions of PRO Instruments

SF-36

For assessment of their health-related quality of life (HRQL), patients completed the SF-36 instrument.25 This instrument consists of 8 partially correlated HRQL scales, all transformed to range from 0 to 100 with higher values reflecting less health impairment: physical functioning (PF), role physical (RP), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role emotional (RE), and mental health (MH). This instrument also includes the 2 summary scores, namely, the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS), which are linear combinations of the 8 scales adjusted for the interscale correlations. The SF-36 scales and summary scores were calculated using the QualityMetric Health Outcomes Scoring Software 4.5 (Lincoln, RI) and the 2009 US population norms, as described before.12

SF-6D

Using items of the SF-36v2 instrument, we also calculated the SF-6D health utility index. Typically, health utility scores are used to appreciate patients’ preference for a quality of life, or to compare healthcare interventions by calculation of quality-adjusted life years to assess cost-effectiveness and other quantifiable metrics.26 In this study, we used a previously reported nonparametric Bayesian algorithm and a scoring program provided to us by the University of Sheffield under the terms and conditions of noncommercial end-user license agreement.

CLDQ-HCV

The CLDQ-HCV is another widely used and validated HRQL instrument developed specifically for assessment of HRQL in patient with chronic HCV infection.27 It includes 29 items and 4 HRQL scales: activity and energy, emotional (EM), worry (WO), and systemic (SY). These scales are averaged to the total CLDQ-HCV score that ranges from 1 to 7 with higher values representing better HRQL.

FACIT-F

The FACIT-F is a fatigue-specific PRO instrument.28 It assesses 5 individual scales, including 4 HRQL scales—physical (PWB), emotional (EWB), social (SWB) and functional (FWB) well-being,–and a fatigue subscale (FS), all added up to a total FACIT-F score (ranges 0–160, with greater values reflecting better health and less fatigue).

WPAI:SHP

The WPAI:SHP instrument assesses impairment in daily activities and work associated with a specific health problem. It includes work productivity impairment (WI) and activity impairment (AI) domains,29 both measured using a 1-week recall period. The WI domain, which is assessed only in individuals who report being currently employed, is a sum of absenteeism and presenteeism domains. Unlike other PROs, higher WI and AI represent worse health status with more impairment (range 0–1 with 1 representing total inability to perform work or activities).

Statistical Analysis

Treatment regimens were grouped into 2 types regardless of treatment duration: RBV ± IFN-containing (IFN + RBV, IFN + RBV + SOF, SOF + RBV, or LDV/SOF + RBV), and IFN-free RBV-free (LDV/SOF). For all collected clinicodemographic parameters, treatment-related adverse events, and treatment outcomes, as well as for all PROs and SF-6D utility scores at all study time points, the prevalence in percent or mean and standard deviation were calculated within each treatment type cohort separately. Pearson χ2 test for independence or a Wilcoxon nonparametric test was used for comparison of these parameters between the treatment type cohorts at all applicable time points. The decrements in PROs and utilities from patients’ own baseline were calculated for each patient at each subsequent time point, and Wilcoxon tests were applied to compare them to zero (sign rank) and between the treatment type cohort (rank sum) where applicable.

Independent predictors of PROs were assessed using multiple linear regression with the use of an IFN-free RBV-free regimen being used as a potential PRO predictor during and after treatment. Other potential PRO predictors were age, sex, BMI, location, baseline hemoglobin, HCV viral load and ALT (at day 1), pre-treatment history of psychiatric disorders self-reported at screening, treatment history, the duration of treatment in weeks, achieving viral clearance (at post-treatment week 4 only), and the presence of cirrhosis.

P values of ≤0.05 were considered potentially significant. All statistical analyses were run in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Each clinical trial included in this study was approved by each site's Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Patient Population

A total of 4485 CH-C patients were treated with different SOF-based regimens in the 12 trials. Of these, 106 patients indicated to be of Asian ancestry (55.7% male, 40.6% enrolled in the United States, 69.8% treatment-naïve, 17.0% cirrhotic). In comparison with other CH-C patients, the Asian CH-C cohort was younger (46.5 ± 11.6 vs 52.2 ± 9.9 years, P < 0.001), had lower BMI (25.6 ± 4.5 vs 27.4 ± 5.2, P < 0.001), and lower rates of pretreatment psychiatric comorbidities (anxiety 3.8% vs 17.0%, P < 0.001, depression 9.4% vs 26.4%, P < 0.001, sleep disorders 4.7% vs 19.3%, P < 0.001). The rates of cirrhosis, anti-HCV treatment history, as well as the rates of pretreatment type 2 diabetes mellitus or hyperglycemia and clinically overt fatigue were similar between Asian and non-Asian patients (all P > 0.05).

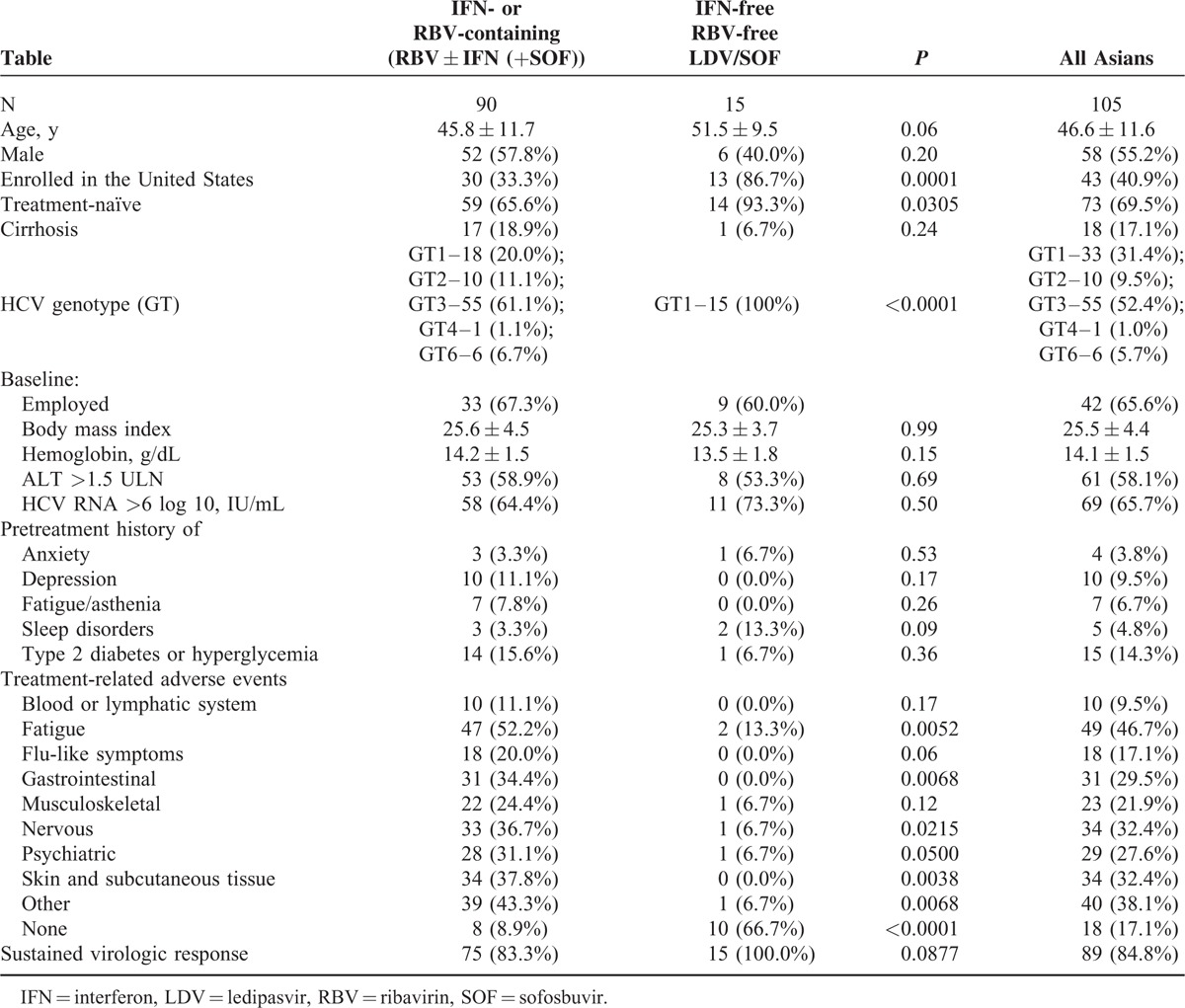

Treatment regimens included those that contained IFN and/or RBV with or without SOF (RBV ± IFN [+SOF]; N = 90) and those which were free of IFN and RBV (LDV/SOF; N = 15). Treatment duration varied from 8 to 24 weeks. Demographics and baseline clinical parameters of the Asian patients were similar between the treatment type cohorts, except for the location and treatment history (owing to the design of the trials, since different treatment regimens were studied in different CH-C populations and also in different countries)17–23 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Clinical Presentation of Asian Patients Treated With Anti-HCV Regimens

As compared with RBV ± IFN-containing regimens, patients receiving IFN-free RBV-free LDV/SOF were less likely to experience adverse effects from treatment (8.9% in RBV ± IFN [+SOF] vs 66.7% in LDV/SOF experienced no treatment-related side effects, P < 0.001). In particular, this was true for treatment-related fatigue (13.3% in LDV/SOF vs 52.2% in RBV ± IFN (+SOF), P < 0.001), gastrointestinal (0.0% vs 34.4%, respectively, P < 0.001), nervous (6.7% vs 36.7%, P = 0.02), psychiatric (6.7% vs 31.1%, P = 0.05), skin (0.0% vs 37.8%, P = 0.0038), and other disorders (6.7% vs 43.4%, P = .0068) (Table 1).

Patient-reported Outcomes in Chronic Hepatitis C Patients of Asian Ancestry

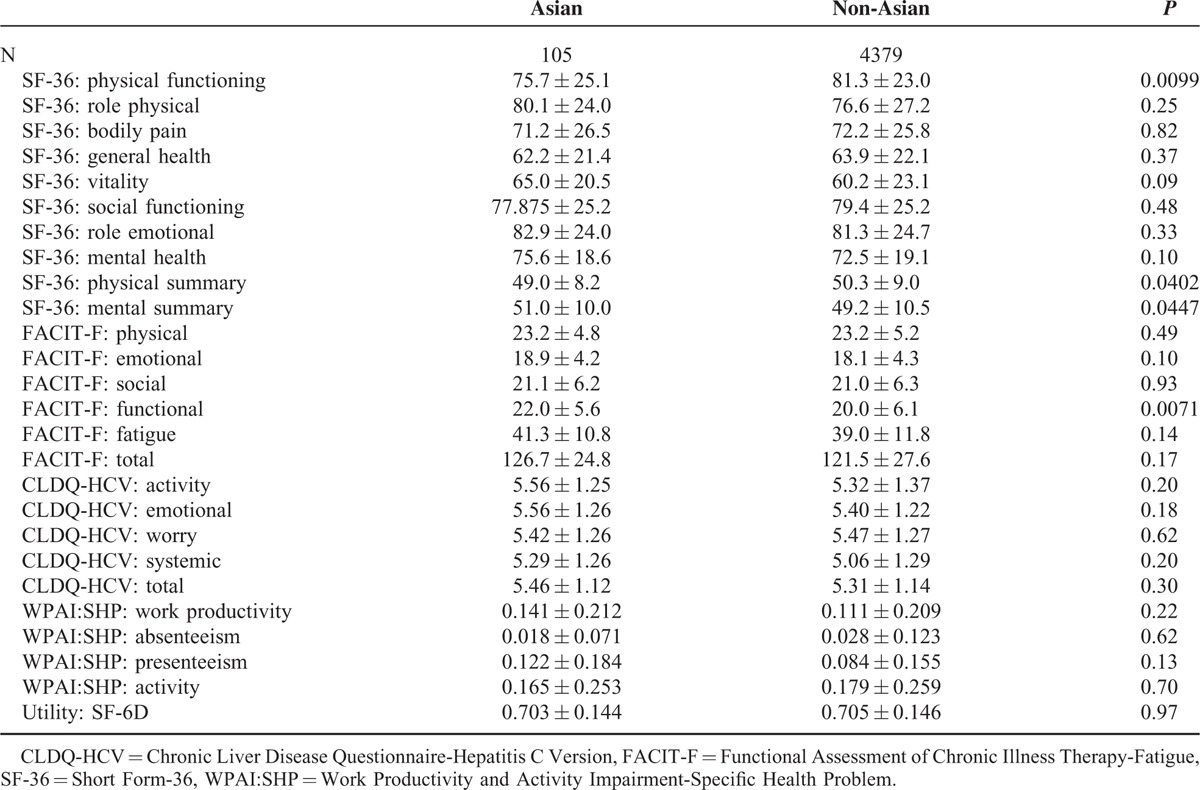

When compared with other CH-C patients, the SF-36 PF scores were lower in Asians (Table 2). This may have been related to slightly lower baseline hemoglobin in these patients (14.1 ± 1.6 vs 14.7 ± 1.3 g/dL, P < 0.001). However, Asian patients with CH-C had slightly higher baseline SF-36 MH scores and FACIT-F functional scores compared with patients of other ethnicities (Table 2). In the Asian cohort, there were no differences in PRO scores by treatment group observed at baseline (all P > 0.05).

TABLE 2.

Baseline Patient-reported Outcomes in Asian and Non-Asian Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C

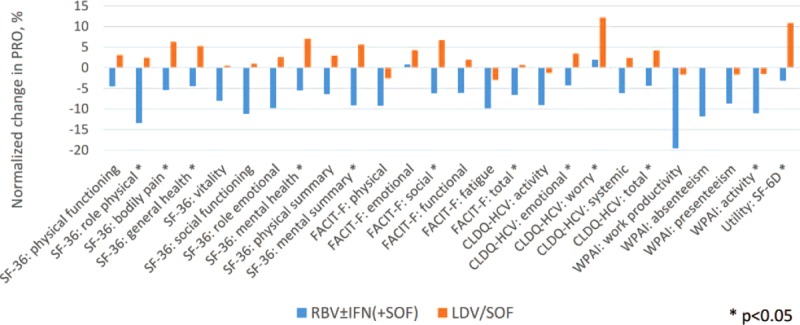

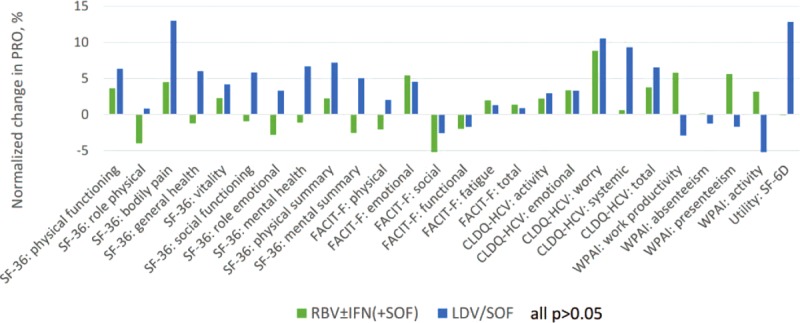

During treatment with IFN-free RBV-free LDV/SOF, Asian CH-C patients showed no significant decrement in their PROs (all P > 0.05). In fact, some PRO improvement in that treatment type cohort was observed starting as early as treatment week 4 (on average, +5.2 in GH of SF-36, +0.7 in WO of CLDQ-HCV, both P < 0.01) (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1). By the end of treatment (Figure 2), the average improvement in GH became more prominent: +9.0 (P = 0.034); in fact, 66.7% of Asian patients experienced at least some improvement in GH by the end of treatment with the IFN-free RBV-free LDV/SOF regimen.

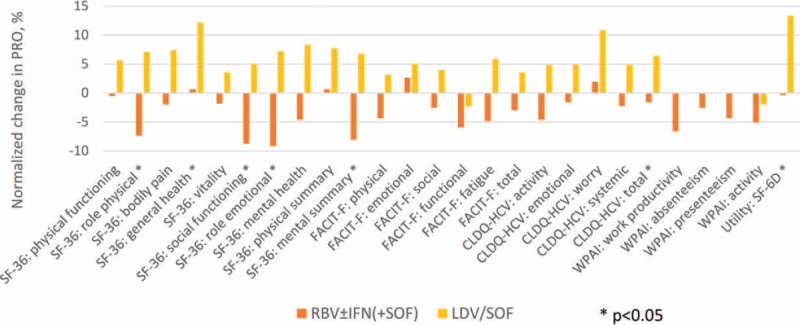

FIGURE 1.

Changes in PROs in Asian patients by treatment week 4 with sofosbuvir-containing regimens. The PROs are normalized to a 0%–100% scale. Average across all 26 PROs: −7.4% (min −19.5%, max +1.9%) in RBV ± IFN (+SOF); +2.8% (min −3.0%, max +12.2%) in LDV/SOF.

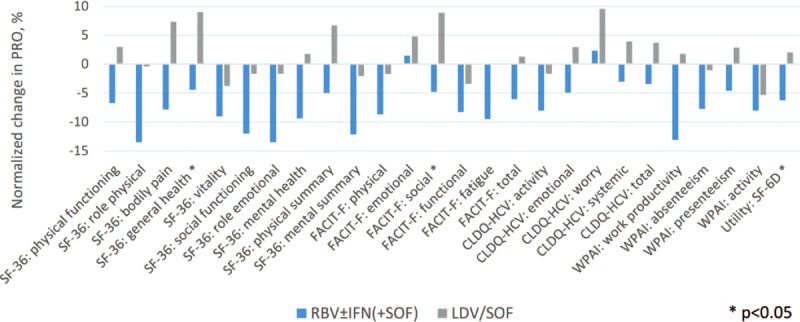

FIGURE 2.

Changes in PROs in Asian patients by the last day of treatment with sofosbuvir-containing regimens. The PROs are normalized to a uniform 0%–100% scale. Average across all 26 PROs: −7.2% (min −13.5%, max +2.3%) in RBV ± IFN (+SOF); +1.8% (min −5.3%, max +9.6%) in LDV/SOF.

In contrast, patients experienced a decline in their PRO scores while receiving RBV ± IFN-containing regimens (Supplementary Table 1 Figures 1–2). In particular, substantial decrements in most of the domains of SF-36, PWB, fatigue, and total of FACIT-F, all but one domains of CLDQ-HCV, and work productivity and activity of WPAI:SHP were observed starting week 4 of treatment in these patients. By the end of treatment, the majority of these decrements persisted and/or became of a greater magnitude (Figures 1–2, Supplementary Table 1).

By post-treatment week 4, some residual PRO decrement remained in RBV ± IFN-containing treatment arms (Supplementary Table 1 Figure 3), although those were largely of a smaller magnitude. At the same time, PRO improvement in patients who received IFN-free RBV-free treatment became greater (on average, +12.2 in GH, P = 0.0029) or achieved statistical significance (EM and total of CLDQ-HCV, SF-6D). In fact, at least some improvement in GH was experienced by 80% of patients, and in all these patients this improvement was equal to or exceeded the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 5% of the range size.

FIGURE 3.

Changes in PROs in Asian patients by post-treatment week 4 with sofosbuvir-containing regimens. The PROs are normalized to a uniform 0%–100% scale. Average across all 26 PROs: −3.3% (min −9.2%, max +2.7%) in RBV ± IFN (+SOF); +5.1% (min −2.3%, max +13.4%) in LDV/SOF.

After achieving SVR-12 (N = 90), all PROs returned to their baseline levels or improved regardless of the regimen (all P > 0.05 between regimens) (Supplementary Table 1 Figure 4). In particular, statistically and clinically (exceeding 5% of the range size) significant improvements were observed in BP of SF-36, EWB of FACIT-F, and WO domain of CLDQ-HCV in Asian CH-C patients with SVR-12 (Supplementary Table 1).

FIGURE 4.

Changes in PROs in Asian patients by post-treatment week 12 with sofosbuvir-containing regimens (SVR-12 only). The PROs are normalized to a 0%–100% scale. Average across all 26 PROs: +1.2% (min −5.7%, max +8.8%) in RBV ± IFN (+SOF); +3.4% (min −13.1%, max +13.0%) in LDV/SOF.

When compared with non-Asians, some baseline differences in PROs were found as described above (Table 2). By treatment week 4 with RBV ± IFN-containing regimens, the decrements in PROs in Asian patients were substantially greater as compared with non-Asians (RP, GH, SF, RE MH, and MCS of SF-36, EWB, FS, and total FACIT-F, WO, SY, and total CLDQ-HCV, and activity of WPAI:SHP [all P < 0.05]) (Supplementary Figure 1A). However, by the end of treatment with RBV ± IFN (+SOF), these magnitudes became similar between Asian and non-Asian patients (all P > 0.05 except for GH) (Supplementary Figure 2A). Greater residual decrements were again observed in Asians by post-treatment week 4 after cessation of treatment with RBV ± IFN (+SOF) (Supplementary Figure 3A). Finally, some post-SVR improvements were not observed in the Asian patients at post-treatment week 12 while being observed in non-Asians, including those in RP and GH of SF-36, and SWB of FACIT-F (Supplementary Figure 4A). In contrast, no significant differences between Asians and non-Asians were found during and after treatment with LDV/SOF (all P > 0.05 after accounting for multiple testing) (Supplementary Figures 1–4B).

Independent predictors of PROs in Asian CH-C patients

In multivariate analysis of Asian patients, the use of IFN-free RBV-free LDV/SOF was consistently associated with better PRO scores during treatment: where significant, betas range from +15.0% to +29.3% (all P < 0.05). Other predictors of PRO impairment were consistent with prior reports.10–17 In particular, pretreatment history of depression was associated with −16.3% to −33.4% in PROs at different off-treatment time points, whereas no association was found during treatment. However, the association of pretreatment history of type 2 diabetes or hyperglycemia with lower PROs was observed at baseline, during and soon after treatment cessation (beta from −12.3% to −30.2%, all P < 0.05). The association of other predictors, such as not having achieved SVR, older age, lower BMI, history of clinically overt fatigue, location, and history of anti-HCV treatment, with decrements in PROs was less consistent across multiple domains and multiple time points (Supplementary Table 2).

In another round of multivariate analysis, Asian ethnicity was tested as a potential predictor of PROs before, during, and after the end of treatment; the entire cohort of patients was used. After adjustment for PRO predictors described above, Asian ethnicity was independently associated with lower PCS at multiple time points (beta from −6.6% to −10.6%), as well as lower self-reported work productivity (beta from −9.0% to −10.0%) and also other PROs at different time points (beta from −4.7% to −10.6%, all P < 0.035) (Supplementary Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the potential impact of RBV- and/or IFN-containing regimens (LDV/SOF) to PROs in CH-C patients of Asian descent. Our data show that Asian patients with CH-C have significant PRO impairment at baseline, which gets exacerbated while being treated with RBV- or IFN-containing regimens. In contrast, these patients experienced no decrement in PROs with LDV/SOF and, in fact, showed improvement in some aspects of their PROs during treatment.

One of the important issues in this cohort was related to the side effects. In fact, Asian CH-C, as compared with non-Asians, experienced significantly more side effects from the RBV ± IFN-containing treatment regiments assigned. Indeed, 91% of Asian patients receiving an IFN- or RBV-containing regimen experienced at least 1 side effect versus 75% of non-Asians (P < 0.001). In particular, they had more fatigue, flu-like symptoms, muscle pain, and skin disorders (data not shown). In contrast, very few to no side effects were reported in Asian patients with the LDV/SOF regimen. These findings are important when interpreting the PROs, and are in contrast to previous reports regarding Asian patients treated for CH-C. Specifically, one previous report suggested that the Asian patients with CH-C were better able to tolerate interferon-based treatments and, therefore, had a higher “cure” rate than white patients.30–32

In this, we showed that in Asians with CH-C SVR was higher in subjects treated with LDV/SOF (83% in RBV ± IFN, 100% in LDV/SOF). Furthermore, patients receiving IFN ± RBV (+SOF) had significant negative changes in some aspect of their PROs during treatment, particularly in the areas of role performance, general health, VT, and well-being. Even more important, these changes occurred earlier during the course of treatment when compared with non-Asian CH-C patients. One potential explanation for a faster decline of PROs during treatment with IFN and/or RBV may be related to body weight since the body weight of Asian patients is generally 10 to 15 kg lower compared with Western patients, in particular the East Asian women.24,30,33,34 In this study, there was also a significant difference in BMI between Asians and non-Asians: 25.6 ± 4.5 vs 27.4 ± 5.2 (P < 0.001). However, all treatment-emergent decrements in HRQL and other PROs were resolved in patients who achieved SVR-12.

On the contrary, Asian CH-C patients who received LDV/SOF were reporting better general health as early as 4 weeks into treatment as compared with both RBV ± IFN-containing arm and to their own baseline levels. This trend also continued throughout treatment and at least by post-treatment week 4, although by SVR-12 time point no statistically significant difference between the treatment regimens was noted.

These are very encouraging findings and are in line with recent data reported on the substantially better PROs for those patients who have received the new anti-HCV regimens without IFN or RBV. A more unique finding of this study with the Asian population is that the use of IFN-free RBV-free LDV/SOF for treatment predicted better PROs over most of other expected predictors such as the absence of psychiatric disorders or type 2 diabetes.

However, in the context of studying PROs and HRQL, it is important to consider the impact of cultural hesitancy for the Asian patients with CH-C to discuss their MH issues. In fact, the Division of Mental Health of the World Health Organization (WHO) offered one of the first definitions that explicitly identified culture as an important determinant of HRQL.31,32 In studies using SF-36 in the Asian population, it was found that Asians may have a different conceptualization of physical and mental health as compared with the Western populations.32,35,36 In this context, researchers need to be aware of these differences when interpreting HRQL findings in patients of different cultural backgrounds and ethnicities.

A major limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size of Asian patients included in the trials, and that the Asian cohort was enrolled in Western countries only. Nevertheless, this is the largest study of PROs in Asian patients with HCV who are treated with the new anti-viral regimens. Furthermore, despite the sample size, we were able to show significant PRO differences related to different anti-HCV treatment regimens.

In summary, our data show that Asian patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with IFN- and/or RBV-containing regimens had substantial reduction in their PROs, most likely owing to unfavorable side effect profile of these regimens. However, the use of IFN- and RBV-free regimens with a fixed-dose combination of ledipasvir and sofosbuvir leads to PRO improvement in Asian patients. Finally, achieving clearance of HCV infection was observed together with significant PRO improvements. These data, once confirmed in larger studies, could inform patients, clinicians, and policy makers about the comprehensive benefit of the new IFN-free RBV-free regimens for patients’ experience and patients’ health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AI = activity impairment, BMI = body mass index, BP = bodily pain, CH-C = chronic hepatitis C, CLDQ-HCV = Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire – Hepatitis C Version, DAA = direct-acting antiviral, EM = emotional, EWB = emotional well-being, FACIT-F = Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue, FS = fatigue subscale, FWB = functional well-being, GH = general health, HCV = hepatitis C virus, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, HRQL = health-related quality of life, IFN = interferon, LDV = ledipasvir, MCS = mental component summary score, MH = mental health, PCS = physical component summary score, PF = physical functioning, PRO = patient-reported outcome, PWB = physical well-being, RBV = ribavirin, RE = role emotional, RP = role physical, SF = social functioning, SF-36 = Short Form-36, SOF = sofosbuvir, SVR = sustained virologic response, SWB = social well-being, SY = systemic, VT = vitality, WHO = World Health Organization, WI = work productivity impairment, WO = worry, WPAI:SHP = Work Productivity and Activity Impairment – Specific Health Problem.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

This study was funded by Gilead Sciences. ZY is a consultant to Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, BMS, GSK, and Intercept. Other coauthors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sievert W, Altraif I, Razavi HA, et al. A systematic review of hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Asia, Australia and Egypt. Liver Int 2011; 31 Suppl 2:61–80.doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.-02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshii E, Shinzawa H, Saito T, et al. Molecular epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in an area endemic for community-acquired acute hepatitis C. Tohoku J Exp Med 1999; 188:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spradling PR, Rupp L, Moorman AC, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infection among 1.2 million persons with access to care: factors associated with testing and infection prevalence. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:1047–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditah I1, Ditah F2, Devaki P3, et al. The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 through 2010. J Hepatol 2014; 60:691–698.doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.014. Epub 2013 Nov 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:293–300.doi: 10.7326/M13-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasitthankasem R1, Vongpunsawad S1, Siripon N1, et al. Poovorawan Y1. Genotypic distribution of hepatitis C virus in Thailand and southeast Asia. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0126764.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126764. eCollection 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manos MM1, Shvachko VA, Murphy RC, et al. Distribution of hepatitis C virus genotypes in a diverse US integrated health care population. J Med Virol 2012; 84:1744–1750.doi: 10.1002/jmv.23399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Younossi ZM, Jiang Y, Smith NJ, et al. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir regimens for chronic hepatitis C infection: Insights from a work productivity economic model from the United States. Hepatology 2015; 61:1471–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Smith BD, et al. The cost-effectiveness, health benefits, and financial costs of new antiviral treatments for hepatitis C virus. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Marcellin P, et al. Hun. Treatment with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir improves patient-reported outcomes: Results from the ION-1, -2, and -3 clinical trials. Hepatology 2015; 61:1798–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Zeuzem S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes assessment in chronic hepatitis C treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin: the VALENCE study. J Hepatol 2014; 61:228–234.doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.003. Epub 2014 Apr 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Nader F, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in chronic hepatitis C patients with cirrhosis treated with sofosbuvir-containing regimens. Hepatology 2014; 59:2161–2169.doi: 10.1002/hep.27161. Epub 2014 Apr 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aggarwal J, Vera-Llonch M, Donepudi M, et al. Work productivity among treatment-naïve patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C infection receiving telaprevir combination treatment. J Viral Hepat 2015; 22:8–17.doi: 10.1111/jvh.12227. Epub 2014 Feb 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. Effects of sofosbuvir-based treatment, with and without interferon, on outcome and productivity of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12:1349–59e13.doi: 0.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Younossi Z, Henry L. Systematic review: patient-reported outcomes in chronic hepatitis C–the impact of liver disease and new treatment regimens. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41:497–520.doi: 10.1111/apt.13090. Epub 2015 Jan 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Sulkowski M, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for treatment of chronic hepatitis C in patients coinfected with hepatitis C virus and HIV: the impact on patient-reported outcomes. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Younossi Z, Henry L. The impact of the new antiviral regimens on patient reported outcomes and health economics of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Liver Dis 2014; 46 Suppl 5:S186–S196.doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.09.025. Epub 2014 Nov 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV, et al. Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1867–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1878–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1889–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1483–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, et al. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1879–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sulkowski MS, Naggie S, Lalezari J, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients with HIV coinfection. JAMA 2014; 312:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu KQ, Freilich B, Brown RS, et al. Impact of Hispanic or Asian ethnicity on the treatment outcomes of chronic hepatitis C: results from the WIN-R trial. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011; 45:720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hays RD, Morales LS. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med 2001; 33:350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 2002; 21:271–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Younossi ZM, Guyatt G, Kiwi M, et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut 1999; 45:295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system. Validation of version 4 of the core questionnaire. Quality of Life Research 1999; 8:604. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. PharmacoEconomics 1993; 4:353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu ML, Chuang WL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in Asia: when East meets West. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 24:336–345.doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. WHOQOL Study Protocol:The development of the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument. 1993; Geneva, Switzerland: Division of Mental Health, World Health Organization, Publication MNH/PSF/93.9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kagawa-Singer M. Bamboo and Oak: A Comparative Study of Adaptation to Cancer by Japanese-American and Anglo-American Cancer Patients [Dissertation]. Los Angeles, CA: Anthropology, University of California at Los Angeles; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng PN, Marcellin P, Bacon B, et al. Racial differences in responses to interferon-beta-1a in chronic hepatitis C unresponsive to interferon-alpha: a better response in Chinese patients. J Viral Hepat 2004; 11:418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan HL, Ren H, Chow WC, et al. Randomized trial of interferon beta-1a with or without ribavirin in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2007; 46:315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leng J1, Lee T, Sarpel U, et al. Identifying the informational and psychosocial needs of Chinese immigrant cancer patients: a focus group study. Support Care Cancer 2012; 20:3221–3229.doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1464-1. Epub 2012 Apr 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ngo-Metzger Q1, Sorkin DH, Mangione CM, et al. Evaluating the SF-36 Health Survey (Version 2) in Older Vietnamese Americans. J Aging Health 2008; 20:420–436.doi: 10.1177/0898264308315855. Epub 2008 Apr 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.