Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Abstract

Syndromic diarrhea/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome (SD/THE) is a rare, autosomal recessive and severe bowel disorder mainly caused by mutations in the tetratricopeptide repeat domain 37 (TTC37) gene which act as heterotetrameric cofactors to enhance aberrant mRNAs decay. The phenotype and immune profiles of SD/THE overlap those of primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs).

Neonates with intractable diarrhea underwent immunologic assessments including immunoglobulin levels, lymphocyte subsets, lymphocyte proliferation, superoxide production, and IL-10 signaling function. Candidate genes for PIDs predisposing to inflammatory bowel disease were sequencing in this study.

Two neonates, born to nonconsanguineous parents, suffered from intractable diarrhea, recurrent infections, and massive hematemesis from esopharyngeal varices due to liver cirrhosis or accompanying Trichorrhexis nodosa that developed with age and thus guided the diagnosis of SD/THE compatible to TTC37 mutations (homozygous DelK1155H, Fs∗2; heterozygous Y1169Ter and InsA1143, Fs∗3). Their immunologic evaluation showed normal mitogen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation, superoxide production, and IL-10 signaling, but low IgG levels, undetectable antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen and decreased antigen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation. A PubMed search for bi-allelic TTC37 mutations and phenotypes were recorded in 14 Asian and 12 non-Asian cases. They had similar presentations of infantile onset refractory diarrhea, facial dysmorphism, hair anomalies, low IgG, low birth weight, and consanguinity. A higher incidence of heart anomalies (8/14 vs 2/12; P = 0.0344, Chi-square), nonsense mutations (19 in 28 alleles), and hot-spot mutations (W936Ter, 2779-2G>A, and Y1169Ter) were found in the Asian compared with the non-Asian patients. Despite immunoglobulin therapy in 20 of the patients, 4 died from liver cirrhosis and 1 died from sepsis.

Patients of all ethnicities with SD/THE with the characteristic triad of T nodosa, hepatic cirrhosis, and intractable enteropathy have low IgG, poor vaccine response and/or decreased antigen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation. This is now better classified into the subgroup of “well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency” (the update termed as “combined immunodeficiencies with associated or syndromic features”) than “predominantly antibody deficiencies” in the update PIDs classification, and requires optimal interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Syndromic diarrhea/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome (SD/THE) is a rare, autosomal recessive, and severe bowel disorder mainly caused by mutations in the tetratricopeptide repeat domain 37 (TTC37) gene,1 which encodes subunits of the putative human SKI complex that is a heterotetrameric cofactor of the cytoplasmic RNA exosome.2,3 TTC37 mutations have been shown to disturb aberrant RNA decay in multiple systems and to be associated with 5 major presentations: intractable diarrhea possibly after birth, usually leading to failure to thrive and requiring parenteral nutrition; facial dysmorphism with a prominent forehead and cheeks, broad nasal root, and hypertelorism; hair abnormalities such as hair that is woolly and easily removable; immune disorders resulting from defective antibody production; and intrauterine growth restriction.1–5 The age-dependent appearance of these characteristics and low estimated prevalence of SD/THE of around 1/1,000,000 births make it difficult to recognize in the neonatal period,4,5 even though SD/THE is considered to be a well-defined syndrome (OMIM: #614589 or #222470) since 1994.4

Making a differential diagnosis of intractable diarrhea underlying primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs) from epithelial structure anomalies is still challengeable, and some need pathologic and electromicroscopic evidences of disarrangement of the epithelial junctional adhesions.6,7 Before liver cirrhosis, facial dysmorphism or hair anomalies become obvious, “intractable diarrhea,” “failure to thrive,” or “recurrent infections” are 3 of the 10 warning signs of PIDs.8–10 Most children with SD/THE require parenteral nutrition and often immunoglobulin supplementation for hypogammaglobulinemia to prevent recurrent infections and decrease the frequency of diarrhea.5,11

In this study, 2 infants with neonatal intractable diarrhea were referred to our Primary Immunodeficiency Care and Research (PICAR) Institute, and TTC37 mutations were eventually identified after excluding other underlying PIDs. To expand the clinical spectrum of such a rare disease, we reviewed the manifestations of SD/THE in these patients with bi-allelic TTC37 mutations from a literature search, and proposed that SD/THE should be incorporated into the “well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency” category (now changed to “combined immunodeficiencies with associated or syndromic features”) rather than “predominantly antibody deficiencies” in updated PIDs classification12 to increase early awareness and allow for optimal interventions.

METHODS AND PATIENTS

Case 1

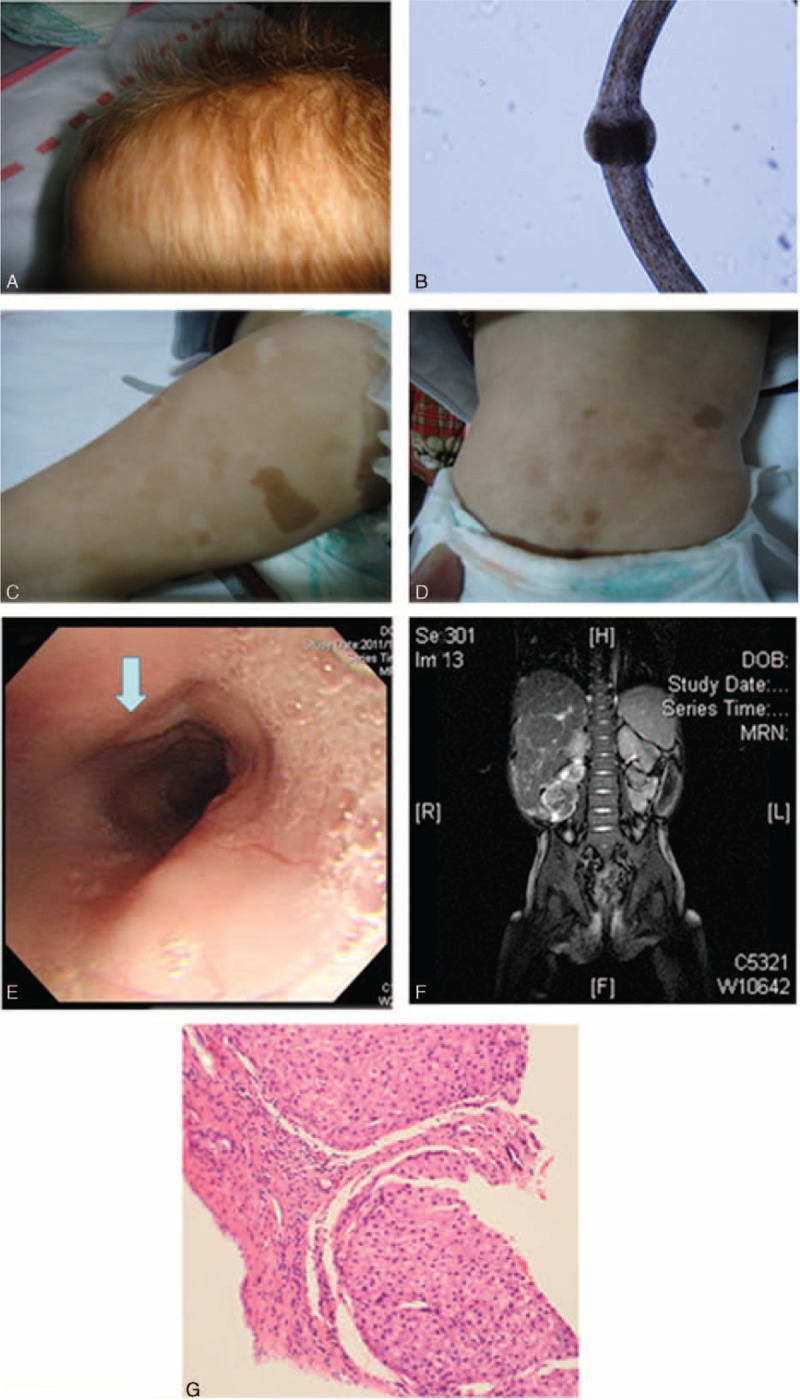

This 1-month-old male infant experienced meconium aspiration and respiratory distress after birth. Coaractation of aorta caused intermittent cyanosis in the intensive care unit. A wide forehead, hypertelorism, light-colored curly hair (Figure 1A and B), and café au lait spots (Figure 1C and D) were noted as he grew. Refractory diarrhea 8 to 10 times/day occurred from 14 days of age despite nil per oral (NPO), empiric antibiotics (ceftriaxone or ceftazidime and amikacin) and steroids. Infectious pathogens for his refractory diarrhea were not detectable by culture or PCR amplification, including HIV. Tandem mass spectrometry showed normal plasma amino acid, urinary organic acid and acylcarnithin profiles, and normal total and free carnithin levels. Serum lactates, pyruvates, ketone bodies, zinc, iron, ferritin, total iron binding capacity, and vitamin B12 were all within normal ranges. Congenital disorders of glycosylation syndrome and cystic fibrosis were excluded. Esopharyngeal varices (Figure 1E) due to liver cirrhosis (Figure 1F and G) caused massive hematemesis, which resolved after conservative treatment at 2 years of age. He also had hypogammaglobulinemia with the severe diarrhea. Under regular immunoglobulin therapy, his diarrhea improved to 3 to 5 times/day and he was grossly healthy at follow-up visits except for 2 hospitalizations due to superimposed severe rotavirus and norovirus enterocolitis over 15 times/day leading to volume depletion.

FIGURE 1.

Significant presentations in case 1 including (A) light-colored curly and fragile hair, (B) microscopic Trichorrhexis nodosa or bamboo hair, (C and D) hyperpigmented café au lait spots on the legs and trunk, (E) hematemesis from esopharyngeal varices, (F) hepatosplenomegaly, and (G) bridging fibrotic septa and nodular formation of hepatocytes, suggestive of cirrhosis in a liver biopsy.

Case 2

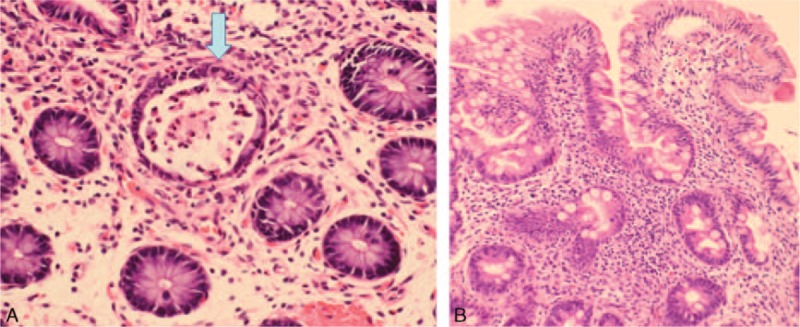

This 5-month-old female infant suffered from intractable diarrhea 8 to 10 times/day after birth regardless of NPO, aggressive antibiotics, and prednisolone. She was term but low birth weight. Colonoscopy and endoscopy revealed nonspecific active colitis with a crypt abscess (Figure 2A), shortened duodenum villi and elongated crypts infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria (Figure 2B). Her refractory diarrhea led to electrolyte exhaustion, hypoalbuminemia, and protein-losing enteropathy. Liver nodular cirrhosis and an atrial septal defect were also noted. She also had respiratory syncytial virus and superimposed Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Despite monthly immunoglobulin therapy, aggressive antibiotic treatment including ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, amikacin, and menopenem failed in her Klebsiella pneumonia sepsis and meningitis, and she subsequently developed multiple-organ dysfunction containing acute respiratory failure, acute kidney failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Unfortunately, she died of arrhythmia due to these critical life-threatening events at 8 months of age.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Colon mucosa showed a picture of nonspecific active colitis, featuring a crypt abscess (arrow) and edematous lamina propria infiltrated with lymphocytes and plasma cells. (B) Higher magnification of the biopsy of the duodenum showed infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria of shortened villi and elongated crypts.

Immunologic Function Assessment

After obtaining approval from our Institutional Review Board and informed consent from the children's parents, 10 to 20 mL of venous blood was collected from the children and controls into heparin-containing syringes and delivered to the laboratory within 24 to 72 h. Basic immunologic laboratory tests including immunoglobulin levels and lymphocyte subpopulations (i.e., CD3+, CD4+, CD4+ CD45RA+, CD4+ CD45RO+ CD19+, CD19+ CD27+, and CD19+ CD27− to calculate T, B, naïve- and memory-T, and memory B cells), lymphocyte proliferation, reactive oxygen species (such as superoxide) production, and IL-10 signaling were evaluated, as previously described.13,14

Candidate Gene Approach

The candidate genes responsible for combined immunodeficiency diseases (CID) with normal or low IgG levels of IL-2 receptor common gamma chain (IL2RG), ZAP70, CD3 gamma, ORAI-1, and ITK; and associated refractory diarrhea in PIDs consisting of IL10, IL10RA, IL10RB, NEMO, FOXP3, XIAP, STAT3, and STAT1 were all sequenced using the Sanger method.15 When liver cirrhosis or Trichorrhexis nodosa became obvious with age, a clinical diagnosis of SD/THE guided candidate gene analysis of the TTC37 gene. Every 2 oligonucleotide primers were selected to cover the entire coding region. The primer sequences were based on the human genome sequences and are available upon request.

PubMed Review

We searched for English-language medical reports on SD/THE with TTC37 mutations in Medline (PubMed and Embase) using the search items “TTC37 mutations” and “diarrhea.” The ethnicity, consanguinity, treatment, intestinal biopsy, liver condition, neurodevelopment, immunoglobulin therapy, prognosis, and location of the mutations of the cases in the relevant studies in the search were analyzed and compared.

RESULTS

Immunology and Gene Analysis

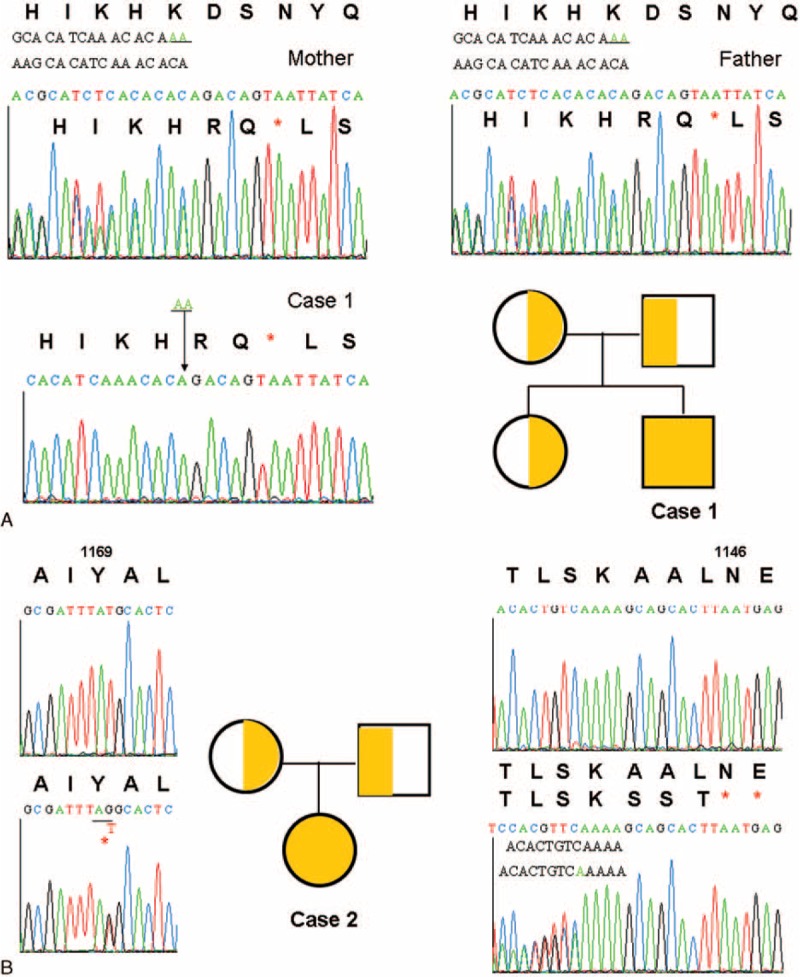

In the absence of family history of incontinentia pigmenti, infant-onset diabetes and immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked (IPEX) syndrome-like phenotype,16–18 the mutation analysis of NEMO, FOXP3, and STAT1 genes was, as expected, all wide type. Chronic granulomatous diseases and dysfunctional IL-10 signaling were excluded by normal reactive oxygen species production and inhibition of TNF-α production after IL-10 signaling activation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from both case 1 and case 2 (data not shown). Their neutrophil counts and lymphocyte subsets including memory cells, naïve lymphocyte, and their dynamic biomarkers of T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs, 324, 252; normal range 73–258 in 250 ng whole blood genomic DNA) and KRECs (κ-deletion recombination excision circles, 218, 176; normal range 60–674 in 250 ng whole blood genomic DNA) were also normal (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). However, their vaccine response to hepatitis B surface antigen was undetectable, and the response to pneumococcus also decreased. Hypogammaglobulinemia and decreased lymphocyte proliferation to antigens (the stimulation index of Candida 10 μg/mL, 3.5 in case 1, 2.1 in case 2 [12.4–58.4 in the controls]; of BCG 0.8 μg/mL, 1.7 in case 1, 1.3 in case 2 [2.8–7.1 in the controls]) but not mitogens (PHA, PWM, and ConA) suggested combined T and B cell immunodeficiency diseases in which genetic defects were not identified through the candidate genetic approach. Because of the presence of light-colored curly hair and liver cirrhosis with mildly elevated liver enzymes, SD/THE was clinically suggested and confirmed by genetic analysis (Figure 3), which revealed a homozygous deletion AA in the TTC37 gene of the 3464th and 3465th nucleotides in 1155K leading to a stop at the 1157th amino acid in case 1, and heterozygous 3724 ins A, Tyr1169Ter in case 2; both at exon 33.

FIGURE 3.

Homozygous deletion AA in the TTC37 gene of the 3464th and 3465th nucleotides in 1155K led to stop at the 1157th amino acid (A). Heterozygous 3507G>T missense mutation and 3724 ins A caused Tyr1169Ter and stopped at the 1146th amino acid. The upper volume showed the normal sequencings (B). TTC37 = tetratricopeptide repeat domain 37.

Literature Review of Patients With Bi-Allelic TTC37 Mutations

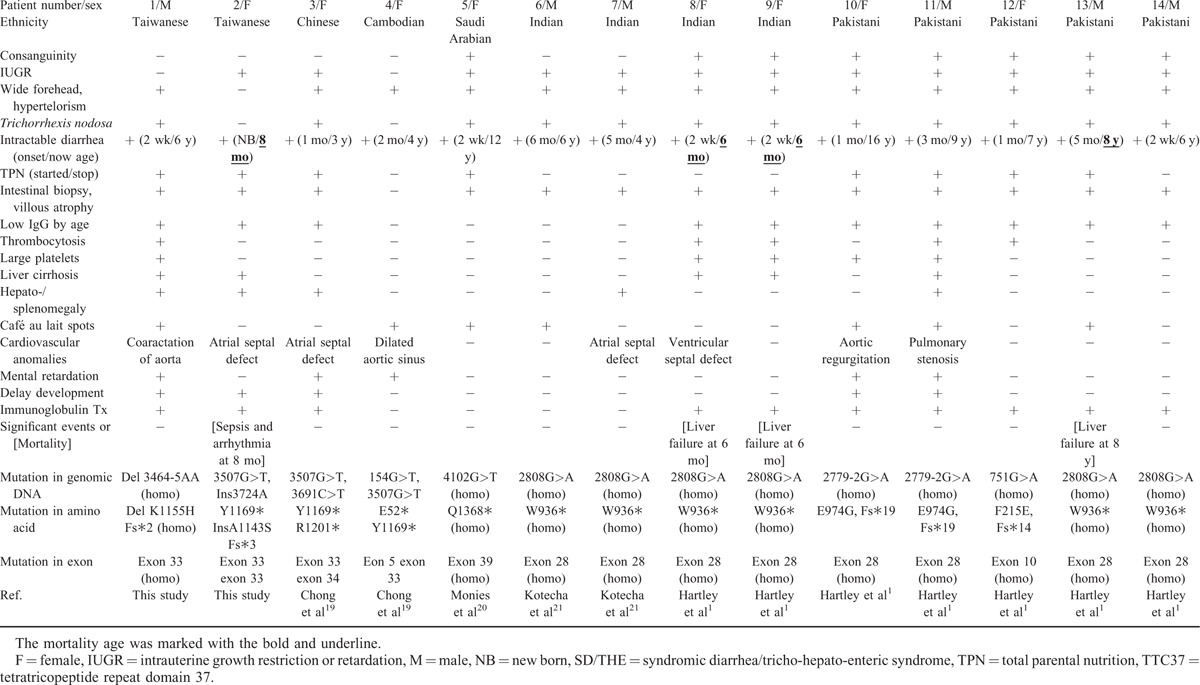

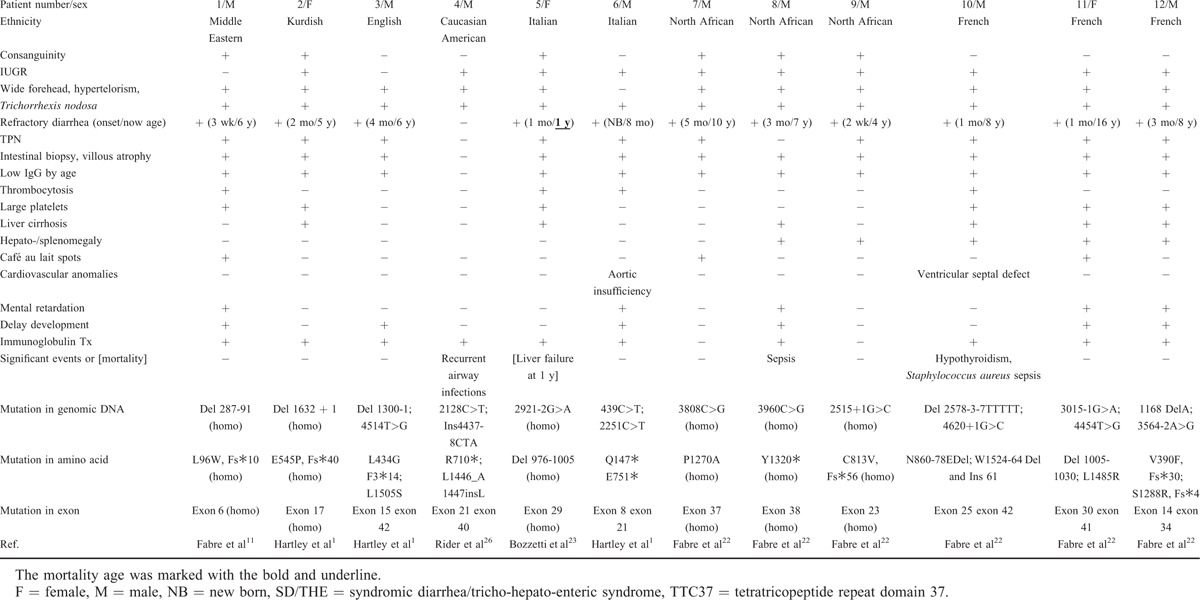

Clinical features, treatment, and mortality of the cases reported in the Medline search were reviewed.1,11,19–23,27 The patients lacking either identified bi-allelic TTC37 mutations or clinical descriptions were not included in the analysis. For the patients of Asian ethnicity, there were our 2 Taiwanese cases, and 1 Chinese,19 1 Cambodian,19 1 Saudi Arabian,20 4 Indian,1,21 and 5 Pakistani cases1 (Table 1). All of the cases had intractable diarrhea compatible with characteristic intestinal villous atrophy and facial dysmorphism except for our case 2 who was too young for facial dysmorphism to be obvious. Interestingly, our other Taiwanese patient (P2) and 2 of the Indian patients (P6 and P7) without consanguinity had homozygous mutations. However, the Gujarat founder mutation of c.2808G>A p.W936∗ at exon 28 was demonstrated in those of Indian and Pakistani ethnicity, including P6–9, P13, and P14 (Table 1), and this caused 12 nonsense mutations in 18 middle Asian alleles (P6–14). The other hot-spot mutation (c.3507G>T p.Y1169∗) in the remaining 5 south Asian patients (P1–5) was located at exon 33 in 6 of 10 south Asian alleles. In all 26 alleles, nonsense mutations (n = 19) were predominant (Supplemental Table 4).

TABLE 1.

Clinical Features of 14 Asian Patients With SD/THE and Bi-Allelic TTC37 Mutations

In the non-Asian patients, there were 1 from the middle East, 1 Kurdish, 1 Caucasian-USA, 1 English, 2 Italian, 3 French, and 3 North African after excluding 2 with only 1 allelic TTC37 mutation of Asp1283Asn in 1 Dutch and 1 French patients.1,11,22–24 The distribution of their mutations was diverse through the whole coding region, and was not clustered at any hot-spot mutation. Their mutation type was more heterogeneous in 24 alleles, including 10 splicing, 5 nonsense, 4 deletion, 4 missense, and 1 insertion mutations (Supplemental Table 4).

Overall, there were no significant differences in the clinical manifestations of SD/THE in the Asian patients compared with the non-Asian patients, and encompassed infantile onset refractory diarrhea, facial dysmorphism, hair anomalies, low IgG, low birth weight, and consanguinity1,11,22–24 except for heart anomalies (P = 0.0344; Chi-square; Supplemental Table 3). In 10 Asian and 10 non-Asian patients who received immunoglobulin therapy, the mortality rate was higher in the Asian patients, of whom 3 died of liver failure and 1 of sepsis and arrhythmia, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Clinical Features of 12 Non-Asian Patients with SD/THE and bi-allelic TTC37 Mutations

DISCUSSION

Using genome-wide linkage analysis, TTC37 mutations were first identified in 5 Pakistani, 2 Indian, and 1 Kurdish infants born to consanguineous parents who were native to Gujarat in 2010,1 and these genetic mutations have been found to be responsible for approximately 60% of cases of SD/THE. The mutant TTC37 gene product, thespin, disturbs RNA exosome to mislocate intracellular enteral transporters and reduce electrolyte exchangers in the intestine, subsequently causing intractable diarrhea that may contribute to the loss of immunoglobulin from the intestine leading to hypogammaglobulinemia. Patients with hypogammaglobulinemia do not have sufficient immunoglobulin to execute defensive neutralization, opsonization, and complement activation.25 In addition, a poor vaccine response to Hemophilia influenza, Tetanus toxoid, Pneumococcus,4,5,11,26 and hepatitis B surface antigens have been demonstrated. Both evidences of hypogammaglobulinemia and a poor vaccine response reflect antibody defects in SD/THE patients, placing them at an increased risk of infections.

To further explore the pathophysiology of TTC37 mutations in immune response, we speculate that a similar structure to TTC7A with tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain mediates protein–protein interactions. TTC7A has been reported to enhance phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIα (PI4K IIIα) located in the intestinal plasma membrane27,28 for cell polarity and gut homeostasis.29 TTC7A can also be expressed in thymic epithelial cells to induce lymphocyte development, cytoskeleton remodeling, and immunologic synapses for proliferation, activation, and effector function.30 Patients with TTC7A mutations present with severe combined T and B cell immunodeficiency, multiple intestinal atresia and intractable neonatal diarrhea.31 Taken together, disturbing the TPR domain for active interactions and releasing nondecay inhibitory RNAs in intestine and thymus,32 TTC37 mutations presumably break intestine homeostasis and downregulate lymphocyte antigen-stimulated proliferation and vaccine response, in consistent with a previous observation.4

Different from intestinal epithelium with mislocated transporter proteins, liver macrolobular hepatoblastoma-like cirrhosis with normal transporter proteins usually appears with age, and the mechanism remains to be clarified. This time lag in the appearance of liver cirrhosis, hepatomegaly or hepatosplenomegaly led to the delay in diagnosis in case 2. In the absence of intractable diarrhea and hepatomegaly, a Caucasian male patient (P4) had aphthous oral ulcers, difficult feeding, and recurrent sinopulmonary infections despite sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim (SMT–TMP) prophylactics. He also had a rapid decline in selective pneumococcus-specific antibody titers but normal total immunoglobulin levels. Whole exome sequencing discovered his heterozygous mutations of the TTC37 gene.26

In the 1990s, Girault et al4 reported that 5 of 8 patients without a genetic diagnosis died of cirrhosis and sepsis in spite of treatment with immunoglobulin, steroids, cyclosporine, and bone marrow transplantation. With advancements in next generation sequencing and immunoglobulin preparation through the 2000s, the 26 patients in this study with identified bi-allelic TTC37 mutations were recognized earlier, and only 4 Asian (immunoglobulin therapy in 2) and 1 non-Asian (immunoglobulin therapy in 1) patients died of liver failure and 1 from sepsis as the same death causes in the 1990s before the era of the Human Genome Project, but lower mortality rate (5/26 vs 5/8; P = 0.0314, Fisher's exact test). While compared with the non-Asian patients, Asian patients have similar features but a higher incidence of heart anomalies (8/14 vs 2/12; P = 0.0344, Chi-squared test), nonsense mutations (19 in 28 alleles) and the presence of hot-spot mutations (W936Ter, 2779-2G>A, and Y1169Ter).

Infants with TTC37 mutations have been reported to present with neonatal intractable diarrhea, and this is a warning sign of PIDs.8–10 Such patients should be referred to a PIDs institute when possible to identify genetic defects which can be used in prenatal genetic analysis in the next pregnancy. This is rational, however, still a challenge for physicians before the characteristic triad appears. With regard to the categories of PIDs, neonatal intractable diarrhea is a critical sign and is classified into the subgroups of “autoinflammatory disorders,” “immunoregulation imbalance,” “phagocyte defects,” and “combined T and B cell defects” with identified candidate genes; however, this classification did not include DS/THE before the forthcoming 2015 PIDs classification.33

In conclusion, DS/THE patients with TTC37 mutations have defective antibody responses despite a normal level of immunoglobulin or low immunoglobulin, and decreased lymphocyte proliferation to antigens. These patients usually have recurrent infections and intractable diarrhea that improve with immunoglobulin therapy, which resembles those with Comel-Netherton syndrome due to the SPINK5 mutation who have hypogammaglobulinemia and impaired natural killer cytotoxicity as well as T nodosa, ichthyosis, epidermal hyperplasia, severe atopic manifestations, and failure to thrive. Their recurrent infections and atopy are improved by immunoglobulin therapy.34 Similar to characteristic triad in Comel-Netherton syndrome, hyper IgE syndromes, and Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome all classified into “well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency,” SD/THE patients have also distinct triads of T nodosa, hepatic cirrhosis (or hepatomegaly) and enteropathy-intractable diarrhea, or facial dysmorphism, and therefore would be better classified as “well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency,” which is now termed as “combined immunodeficiencies with associated or syndromic features” rather than “predominately antibody deficiencies” to raise awareness and allow for effective treatment.

Since this manuscript was submitted on July 20, 2015 and accepted for oral presentation in the 224th Academic Congress of Taiwan Pediatrics Association on August 26, 2015, TTC37 mutations have been incorporated into “predominantly antibody deficiency” on October 19, 2015 [Epub ahead of print] instead of “combined immunodeficiencies with associated or syndromic features” (previous “well-defined syndromes with immunodeficiency”) in the 2015 IUIS (International Union of Immunologic Societies) Expert Committee for primary immunodeficiency.33

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CID = combined immunodeficiency diseases, IPEX = immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked, IUIS = International Union of Immunologic Societies, KRECs = κ-deletion recombination excision circles, OMIM = Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, PIDs = primary immunodeficiency diseases, SD/THE = syndromic diarrhea/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome, TRECs = T-cell receptor excision circles, TTC37 = tetratricopeptide repeat domain 37, TTC7A = tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7A.

This study was funded by grants from Chang-Gung Medical Research Progress (CMRPG 490011) and the National Science Council (NSC 99-2314-B-182A-096-MY3, NSC 102-2314-B-182A-039-MY3, MOST 104-2663-B-182A-005, and NMRPG 3C6071-3).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, et al. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy). Gastroenterology 2010; 138:2388–2398.2398.e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fabre A, Breton A, Coste ME, et al. Syndromic (phenotypic) diarrhoea of infancy/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. Arch Dis Child 2014; 99:35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabre A, Charroux B, Martinez-Vinson C, et al. SKIV2L mutations cause syndromic diarrhea, or trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 90:689–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Girault D, Goulet O, Le Deist F, et al. Intractable infant diarrhea associated with phenotypic abnormalities and immunodeficiency. J Pediatr 1994; 125:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goulet O, Vinson C, Roquelaure B, et al. Syndromic (phenotypic) diarrhea in early infancy. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008; 3:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uhlig HH, Schwerd T, Koletzko S, et al. The diagnostic approach to monogenic very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2014; 147:990–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uhlig HH. Monogenic diseases associated with intestinal inflammation: implications for the understanding of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2013; 62:1795–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa-Carvalho BT, Grumach AS, Franco JL, et al. Attending to warning signs of primary immunodeficiency diseases across the range of clinical practice. J Clin Immunol 2014; 34:10–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subbarayan A, Colarusso G, Hughes SM, et al. Clinical features that identify children with primary immunodeficiency diseases. Pediatrics 2011; 127:810–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carneiro-Sampaio M, Jacob CM, Leone CR. A proposal of warning signs for primary immunodeficiencies in the first year of life. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2011; 22:345–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fabre A, Martinez-Vinson C, Goulet O, et al. Syndromic diarrhea/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013; 8:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova JL, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies expert committee for primary immunodeficiency. Front Immunol 2014; 5:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelhardt KR, Shah N, Faizura-Yeop I, et al. Clinical outcome in IL-10- and IL-10 receptor-deficient patients with or without hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131:825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee WI, Kuo ML, Huang JL, et al. Distribution and clinical aspects of primary immunodeficiencies in a Taiwan pediatric tertiary hospital during a 20-year period. J Clin Immunol 2005; 25:162–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.RAPID. http://web16.kazusa.or.jp/rapid/sequencing [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng LE, Kanwar B, Tcheurekdjian H, et al. Persistent systemic inflammation and atypical enterocolitis in patients with NEMO syndrome. Clin Immunol 2009; 132:124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uzel G, Sampaio EP, Lawrence MG, et al. Dominant gain-of-function STAT1 mutations in FOXP3 wild-type immune dysregulation-polyendocrinopathy-enteropathy-X-linked-like syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 13:1611–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torgerson TR, Ochs HD. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked: forkhead box protein 3 mutations and lack of regulatory T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120:744–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chong JH, Jamuar SS, Ong C, et al. Tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome (THE-S): two cases and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr 2015; 174:1405–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monies DM, Rahbeeni Z, Abouelhoda M, et al. Expanding phenotypic and allelic heterogeneity of tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015; 60:352–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotecha UH, Movva S, Puri RD, et al. Trichohepatoenteric syndrome: founder mutation in Asian Indians. Mol Syndromol 2012; 3:89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fabre A, Martinez-Vinson C, Roquelaure B, et al. Novel mutations in TTC37 associated with tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. Hum Mutat 2011; 32:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozzetti V, Bovo G, Vanzati A, et al. A new genetic mutation in a patient with syndromic diarrhea and hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 57:e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabre A, André N, Breton A, et al. Intractable diarrhea with “phenotypic anomalies” and tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome: two names for the same disorder. Am J Med Genet A 2007; 143A:584–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mak TW, Saunders ME. B cell development, activation and effector functions. Primer to the Immune Response 2011; Burlington, MA: Elsevier, 94-95. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rider NL, Boisson B, Jyonouchi S, et al. Novel TTC37 mutations in a patient with immunodeficiency without diarrhea: extending the phenotype of trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Front Pediatr 2015; 3:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakatsu F, Baskin JM, Chung J, et al. PtdIns4P synthesis by PI4KIIIα at the plasma membrane and its impact on plasma membrane identity. J Cell Biol 2012; 199:1003–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avitzur Y, Guo C, Mastropaolo LA, et al. Mutations in tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7A result in a severe form of very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2014; 146:1028–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bigorgne AE, Farin HF, Lemoine R, et al. TTC7A mutations disrupt intestinal epithelial apicobasal polarity. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen R, Giliani S, Lanzi G, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7A (TTC7A) mutations for combined immunodeficiency with intestinal atresias. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132:656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemoine R, Pachlopnik-Schmid J, Farin HF, et al. Immune deficiency-related enteropathy-lymphocytopenia-alopecia syndrome results from tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7A deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134:1354–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fabre A, Badens C. Human Mendelian diseases related to abnormalities of the RNA exosome or its cofactors. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2014; 3:8–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Picard C, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the international union of immunological societies expert committee for primary immunodeficiency 2015. J Clin Immunol 2015; 35:727–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renner ED, Hartl D, Rylaarsdam S, et al. Comèl-Netherton syndrome defined as primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124:536–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.