Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to (a) examine how acculturation and social support inform Latinos’ parenting behaviors, controlling for gender and education; (b) describe parenting styles among Latino immigrants while accounting for cultural elements; and (c) test how these parenting styles are associated with family conflict. A 3 step latent profile analysis with the sample (N = 489) revealed best fit with a 4 profile model (n = 410) of parenting: family parenting (n = 268, 65%), child-centered parenting (n = 68, 17%), moderate parenting (n = 60, 15%), and disciplinarian parenting (n = 14, 3%). Parents’ gender, acculturation, and social support significantly predicted profile membership. Disciplinarian and moderate parenting were associated with more family conflict. Recommendations include integrating culturally based parenting practices as a critical element to family interventions to minimize conflict and promote positive youth development.

Latino families and children represent nearly 17% of the U.S. population (Pew Research Center, n.d.); over 10 million children in the United States are children of Latino immigrants (Urban Institute, n.d.). Latino immigrants include those with origins in Mexico, Central America, and South America; thus, this population is very diverse. Many Latino families, particularly those who are undocumented or recent immigrants, live in stressful and impoverished environments and encounter many challenges related to poverty, limited English proficiency, documentation status, acculturation, and discrimination (Ayón & Becerra, 2013; Bacallao & Smokowski, 2013). These factors place youth at risk for engaging in risky behavior (Love & Buriel, 2007), while also affecting parents’ sense of self-efficacy and ability to parent effectively (Bermúdez, Zak-Hunter, Stinson, & Abrams, 2014; Ceballo, Kennedy, Bregman, & Epstein-Ngo, 2012).

Parenting is central in the lives of Latinos (Parra-Cardona, Córdova, Holtrop, Villarruel, & Wieling, 2008). Latino parenting has been described as “nontraditional,” because parenting practices in Latino cultures are often not consistent with predominant parenting styles found in the dominant culture (Domenech Rodriguez, Donovick, & Crowley, 2009). Informed by an ecodevelopmental framework, the aim of the present study was to collectively assess common parenting practices and cultural values, while classifying parenting styles among Latino parents; thus, cultural values were treated as integral to Latino parenting. For instance, cultural values such as familismo inform parenting practices and the socialization of Latino children (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2007). Acculturation and social support were used in the latent profile analysis (LPA) as predictors of profile membership, as they are key cultural constructs that may influence Latino parenting and parents’ ties to traditional values. The final step in the model involved assessing the association between the identified parenting styles and family conflict. The study presents a culturally grounded and informed perspective on Latino parenting and family outcomes.

Parenting Styles

The most prevalent conceptualization of parenting is based on the seminal work of Diana Baumrind (1966), which classifies parents based on the intersection of demandingness and responsiveness. Parental demandingness, or control, is characterized by parenting practices that emphasize supervision, monitoring, and discipline, as well as limit-setting and high expectations. Parental responsiveness, or warmth, connotes acceptance, supportiveness, involvement, communication, and receptiveness to the perspectives and needs of the child. Baumrind’s threefold model of parenting consists of authoritative, authoritarian, and indulgent parenting. It was subsequently modified by Maccoby and Martin (1983) into a fourfold typology, which added neglectful parenting. Authoritative parents are both highly responsive and demanding; authoritarian parents, while demanding, lack responsiveness; indulgent or permissive parents are highly responsive, but not demanding; and neglectful parents are neither responsive nor demanding. The crosscultural application of this typology to diverse populations is disputed. Some researchers question the universal suitability of a model that was developed largely with middle-class European Americans, asserting it is value- and culture-laden with limited transference to other populations including Latinos (Domenech Rodriguez et al., 2009; García Coll & Pachter, 2002).

Latino Parenting

A review of the literature characterizing Latino parenting based on Baumrind’s framework is inconclusive. Some studies have found that Latinos practice more authoritarian parenting (Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003), while others have found that they use more authoritative practices (Varela et al., 2004; Calzada, Huang, Anicama, Fernandez, & Miller Brotman, 2012). Hill et al. (2003) found the low-income Mexican American parents in their sample were characterized by hostile control and inconsistent discipline suggestive of authoritarian parenting. In contrast, Calzada et al. (2012) reported that their sample of Mexican and Dominican parents used more authoritative strategies, such as conversing with children about choices and consequences. Similarly, Varela et al. (2004) conducted a study with Mexican descent and Anglo parents, concluding that, overall, Mexican descent parents used authoritative practices more frequently, but were also more likely to implement authoritarian strategies compared to Anglo parents. Alternatively, Domenech Rodriguez et al. (2009) found that Latino parents engage in protective parenting, and Fischer, Harvey, and Driscoll (2009) reported that Latina mothers name firm control as a parenting value. Varela et al. found that, compared to nonimmigrant Mexican parents, Mexican American parents used more authoritarian strategies, indicating that this trend may be an adaptive strategy in response to contextual stressors (e.g., low-income neighborhoods). Several study design factors may provide plausible explanations of discrepant findings, including use of observation versus self-report, differences in measures used, incompatible operationalization of key concepts, and divergent samples given the heterogeneity of Latinos.

Cultural values

Guilamo-Ramos et al. (2007) argued that Latino parents can be understood within a demandingness and responsiveness framework as long as imperative cultural constructs and values are considered. Despite significant heterogeneity within the population, several cultural values are salient among Latinos. These cultural features influence socialization practices, making Latino parents distinct from other parents (García Coll & Pachter, 2002; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2007). The present study focused on familismo, the cultural orientation and sense of obligation to family (Sotomayor-Peterson, Figueredo, Christensen, & Taylor, 2012). Familismo leads to socialization practices that foster interdependence and sociocentrism in Latino children (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2007). Familismo has been proposed to promote more controlling dispositions among Latino parents (Halgunseth, Ispa, & Rudy, 2006). Other studies, however, have found familismo to be correlated with greater parental warmth (Gonzales et al., 2011), as well as involvement and monitoring (Santisteban, Coatsworth, Briones, Kurtines, & Szapocznik, 2012; Romero & Ruiz, 2007). This position supports findings that, compared to Anglo fathers, Latino fathers engage in more monitoring and socializing activities with their children, such as visiting friends and family with children; in this way, Latino fathers reinforce the value of familismo (Shears, 2007).

Acculturation

This status refers to the extent to which one’s cultural practices have shifted as a result of influences from the dominant culture (Fuller & García Coll, 2010). Higher levels of maternal acculturation have been matched with decreases in antagonistic parenting and more egalitarian parenting (Parke et al., 2004). Calzada et al. (2012) found that parents with higher levels of acculturation used more authoritative parenting practices and valued instilling independence. Another study found more acculturated parents to have strict and controlling dispositions toward their children (Hill et al., 2003).

Social support

As a culture characterized by collectivist values and interdependence, Latinos often receive more social support from family who serve a protective resource-sharing role (Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, Marín, & Perez-Stable, 1987). Prelow, Weaver, Bowman, and Swenson (2010) found social support to buffer the negative effects of ecological risk on maternal parenting by reducing psychological distress. For Mexican immigrant mothers, social support was found to be a predictor of greater self-efficacy as a mother, increasing both parental warmth and control (Izzo, Weiss, Shanahan, & Rodriguez-Brown, 2000).

Parenting, Family Conflict, and Child Outcomes

A number of parenting-related risk and protective factors for conflict within Latino families have been substantiated in the literature. Barber (1994) found high parental expectations to be a protective factor against parent–adolescent conflict. Studies have also suggested that familismo may lead to less familial conflict (Sotomayor-Peterson et al., 2012). Concomitantly, familismo has been associated with a reduction in antisocial behaviors by way of increased parental monitoring (Romero & Ruiz, 2007). Additionally, it has been related to better social problem-solving skills and self-efficacy (Leidy, Guerra, & Toro, 2010) and to less externalizing behaviors, such as substance use, among adolescents (Marsiglia, Parsai & Kulis, 2009).

Other parenting-related factors have been linked with better child outcomes among Latinos as well. Allen et al. (2008) reported that a larger extended family network and greater parental monitoring were related to a reduction in substance use among Latino adolescents. Additionally, supportive parenting was linked with a reduction in internalizing problems (Barrera et al., 2002), and maternal warmth was correlated with less externalizing behavior among adolescents (Gonzales et al., 2011).

This study was informed by an ecodevelopmental perspective (Coatsworth, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2002), which suggests that youth are influenced by multiple aspects of their ecological systems (micro-, meso-, macro-, and exosystem) as they mature through the developmental stages (Coatsworth et al., 2002). The microsystem involves the child’s interactions in different settings (i.e., family, school, peers). Within the microsystem, the family has the greatest influence on youth (Pantin, Schwartz, Sullivan, Coatsworth, & Szapocznik, 2003). The mesosystem includes relationships between microsystems, such as parent–peer relationships. Relationships in the exosystem impact children indirectly and occur entirely independent of the child (Coatsworth et al., 2002). For instance, Latino immigrant parents who have a strong social support system that provides emotional and instrumental support in stressful times may parent more positively. Macrosystems involve broader ideological and cultural patterns. Thus, it is assumed that cultural elements are inherent in parenting (Schwartz et al., 2013), yet immigrant parents’ connection to their culture of origin may decrease over time or be influenced by policies and practices that aim to support assimilation (i.e., English-only policies). Furthermore, this framework posits that the family context, including cohesion, conflict, and communication, are predictors of developmental outcomes for youth (Pantin et al., 2003).

The purpose of the present study was to (a) examine how acculturation and social support inform Latinos’ parenting behaviors, (b) describe parenting styles among immigrant parents while accounting for cultural elements, and (c) test how these parenting styles are associated with family conflict. Drawing from the ecodevelopmental perspective, the authors hypothesized that the majority of Latino immigrant parents would be classified as high on the cultural element of familismo, leading to more effective parenting (i.e., less family conflict). This exploration adds to our understanding of parenting among Latinos by illuminating the ways in which cultural values (e.g., familismo) inform parenting styles. Furthermore, it assessed the relationship between parenting styles and family outcomes, a precursor to child outcomes. By treating culture as an integral part of parenting, the results from this study can inform practice with Latino immigrant families and intervention development. These findings may highlight factors that can be emphasized in interventions with Latino families as well as provide a direction for future research.

Method

This study is based on baseline data from a larger effectiveness trial study. Schools were identified as eligible if they received Title 1 funds, had a population of Latino students greater than 60%, and had at least 100 Latino students. All schools (n = 8) were located in a major metropolitan area in the southwest United States. The schools were stratified into three blocks according to their percentage of Latino students; within each block, they were randomly assigned into three conditions. All schools were randomized prior to being asked to agree to participate in the study. All parents who completed the pretest were included in this study.

In collaboration with a community partner, trained study personnel initiated recruitment procedures at each school. Following human subjects’ approval, parents were invited by telephone and flyer to attend an introductory parent information session, which explained the parenting program to be offered at the school. The parental consent forms emphasized the voluntary and confidential nature of participation and the timing of both youth and parent surveys, as well as informed parents in the intervention group of the implementation of the youth intervention. The analytic sample in the present study included only baseline parent survey data. All surveys were administered by trained research staff, and 98% were completed in Spanish.

Participants

Of the 489 parents that participated in this study, an overwhelming majority were female (85%) and living with a spouse or partner (82%). Regarding nationality, 93% were Mexican-born, but only 17% had lived in the United States for 10 years or less. The mean age was 38 years (SD = 7.56). In terms of education, 40% had not completed high school, with the remaining parents reporting having a high school diploma or GED (36%) or more education (24%). The average household was composed of five members (SD = 1.66), and 52% of parents reported a household income of $20,000 or less.

Measures

Parenting

Parenting was assessed using five self-report scales, including involvement, monitoring, agency, self-efficacy in disciplining, and familismo. The involvement scale consisted of 10 items, such as “Do you and your youth do things together at home?” and had a range of 10 to 50; a higher score indicated greater parental involvement (α = .79). The monitoring (α = .83) and agency (α = .70) scales consisted of eight items, ranging from 5 to 40; higher scores indicated more parental monitoring and agency. For the monitoring and agency scales, respective sample questions included “Do you usually know what type of homework your child has?” and “I feel sure of myself as a mother/father.” The self-efficacy in disciplining scale consisted of seven items, such as “I am a good enough disciplinarian for my child.” The scale had a range of 6 to 42, with a higher score indicating greater parental self-efficacy in disciplining (α = .81). The familismo scale consisted of six items, such as “Parents should teach children that the family always comes first.” The scale had a range of 5 to 30, and a higher score indicated more familismo (α = .98).

Predictors/covariates

Mexican-orientation (α = .77) and Anglo-orientation (α = .85) subscales were included as predictors/covariates in the analysis. Each subscale had six items and a range of 5 to 30, with higher scores indicating more Mexican or Anglo orientation. Respective sample questions for the Mexican- and Anglo-orientation scales included “I think in Spanish” or “I speak in English.” A 10-item social support scale (α = .94) was also included, ranging from 7 to 70, with a higher score indicating more social support. A sample item was, “I have someone with whom I can talk about my problems.” Education, ranging from 1 = did not complete high school to 6 = earned a post-graduate degree, and gender, 1 = male and 2 = female, were additional control variables in the model.

Outcomes

The outcome measure was an eight-item family conflict scale (α = .76), with questions such as “How often do you disagree with your adolescent about lying to a parent?” The scale ranged from 6 to 48, with a higher score indicating more family conflict.

Analysis

The sampling design was structured such that students were nested within schools. We first estimated the clustering effects to determine if misprecision could be in our results (e.g., inflated standard errors). To do this, we calculated the intraclass correlation (ICC) and the design effect (DE) for all exogenous variables: involvement (ICC = 0, DE = 1.000), monitoring (ICC = .007, DE = 1.152), agency (ICC = 0, DE = 1.000), self-efficacy in disciplining (ICC = .004, DE = 1.082), familism (ICC = .005, DE = 1.100), and family conflict (ICC = .002, DE = 1.048). The recommendations by Muthén and Satorra (1995), based on simulation studies, are that standard approaches can be applied with a DE of less than 2.0; therefore, we proceeded with conventional statistical analyses without accounting for the nonindependence of observations.

A three-step LPA model was run using Mplus version 7.11. A strength of LPA is that it allows for the identification of groups or clusters of respondents. Profiles of participants were determined based on five distinct parenting strategies. The best fitting mixture model was not merely basing a model choice on k profiles fitting better than k − 1 profiles. The likelihood ratio comparing a k − 1 and a k profile model does not have the usual large sample chi-square distribution due to the profile probability parameter being at the border (zero) of its admissible space. A commonly used alternative procedure is the Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwartz, 1978) defined as BIC = − 2logL + plnn, where p is the number of parameters and n is the sample size. Here, BIC is scaled so that a small value corresponds to a good model with a large log-likelihood value and not too many parameters (Muthén, 2004). Thus, the best fitting model, or smallest BIC value, in this study corresponded to four latent profiles. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) is a similar model-fit statistic where a lower value indicates a better model fit. Four profiles provided an optimal combination of model fit, parsimony, and interpretable groups (see Table 1 for a comparison of models that tested two through five profiles).

Table 1.

Model Fit Statistics for 2–5 Latent Profiles

| Fit profiles | AIC | BIC | Adjusted BIC | Entropy | LMR | PBLR | N for each profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Profiles | 3651.281 | 3735.621 | 3668.984 | .993 |

1023.540 p < .001 |

0.0000 | c1: 68 (17%) c2: 342 (83%) |

| 3 Profiles | 3351.996 | 3480.513 | 3378.971 | .964 | 316.503 p = .06 |

0.0000 | c1: 68 (17%) c2: 305 (74%) c3: 37 (9%) |

| 4 Profiles | 3237.200 | 3409.895 | 3273.448 | .915 | 134.760 p = .08 |

0.0000 | c1: 68 (17%) c2: 268 (65%) c3: 14 (3%) c4: 60 (15%) |

| 5 Profiles | 3245.653 | 3462.526 | 3291.174 | .925 | 133.183 p = .07 |

0.0000 | c1: 68 (17%) c2: 13 (3%) c3: 264 (64%) c4: 2 (0.5%) c5: 63(15%) |

Note. The best fit values are in bold: lowest adjusted BIC; entropy closest to 1; p < .05 for LMR and PBLR. Four-profile solution represents the best fit. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; LMR = Lo–Mendell–Rubin test; PBLR = parametric bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

LPA yields a probability that any respondent is a member of each group (Osgood et al., 2005). The findings from the four-profile solution indicated that participants were not likely to fall into more than one profile. The most common approach for comparing groups is to assign respondents to the group for which they have the highest probability of membership (Osgood et al., 2005). Although typically there is a risk of distorting the portrayal of some profiles, the risk was near negligible in the present study because the probability of participants falling into more than one group approximated zero. The Mplus software gives the probability of membership scores for each profile per person and also provides a score (1–4) of the profiles of most probable membership. The estimator used in LPA is maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors. Full information maximum likelihood is used to handle missing data. That is, a likelihood function for each participant in the study was estimated based on all available data.

Results

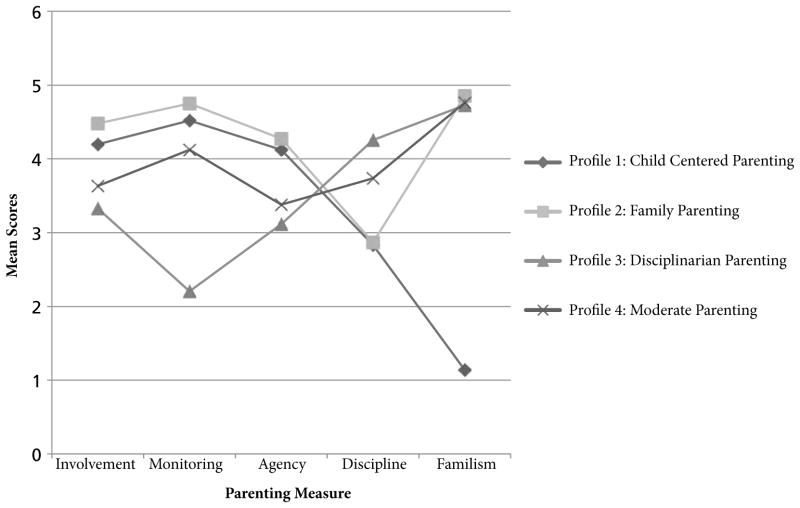

A four-profile solution resulted in the best model fit (lowest AIC, BIC, adjusted BIC, significant parametric bootstrap likelihood ratio test, and a Lo–Mendell–Rubin test; see Table 1 and Figure 1). The four parenting profiles include child-centered parenting (Profile 1, 17% of parents; high involvement, monitoring, and agency; low self-efficacy in disciplining and familismo), family parenting (Profile 2, 65% of parents; high involvement, monitoring, agency, and familismo; low discipline self-efficacy), disciplinarian parenting (Profile 3, 3% of parents; high-discipline self-efficacy and familismo; low involvement, monitoring, and agency), and moderate parenting (Profile 4, 15% of parents; high familismo; moderate involvement, monitoring, agency and discipline self-efficacy). Being female (OR = 3.48) and greater Mexican orientation (OR = 2.13) and Anglo orientation (OR = 1.56) predicted child-centered parenting. That is, child-centered parenting characterized more females (3.5 times that of males), those with higher Mexican orientation (more than twice that of lower Mexican orientation) and Anglo orientation (more than 1.5 times that of lower Anglo orientation). Greater support predicted family parenting (OR = 1.49). That is, family parenting characterized those with higher support (more than 1.5 times that of lower support). Lower Mexican orientation (OR = .27) and Anglo orientation (OR = .19) predicted disciplinarian parenting. That is, disciplinarian parenting characterized those with lower Mexican orientation (more than 3.5 times that of higher Mexican orientation) and Anglo orientation (more than 5 times that of higher Anglo orientation). Child-centered (B = −.42, SE = .19, β = −2.19, p < .05) and family (B = −.62, SE = .17, β = −3.58, p < .001) parenting styles were associated with less family conflict, while disciplinarian (B = .88, SE = .32, β = 2.73, p < .01) and moderate (B = .42, SE = .19, β = 2.19, p < .05) parenting styles were associated with greater family conflict, all at greater than 2 standard deviations.

Figure 1.

Latent Profiles for Latino Parents

Discussion

Informed by the ecodevelopmental perspective, the purpose of this article was to (a) identify parenting styles while accounting for cultural practices and norms among a sample of Latino parents, (b) assess the role of acculturation and social support in predicting parenting profile membership, and (c) assess the relationship between parenting profiles and family conflict. The results supported the study’s hypothesis; most parents reported following a culturally grounded and family-centered approach to parenting, which resulted in effective parenting with low levels of family conflict.

Four parenting profiles were identified within the sample. A majority of parents (65%) were classified into the family parenting style. In this profile, parents had the highest scores in involvement, monitoring, agency, and familismo and a lower score in discipline. Most of the participants were first-generation immigrants. Immigrant parents tend to be very involved with their children, as they want them to be successful in school (Marsiglia, Nagoshi, Parsai, Booth, & Castro, 2014). In addition, two-parent immigrant families with children under the age of 18 are more likely to live in poverty than the general U.S. population (17% compared to 6%; Migration Policy Institute, n.d.), thus potentially heightening the need for monitoring. Within the recent anti-immigrant context, many immigrant families have been confronted with discrimination (Ayón & Becerra, 2013), which may also promote monitoring and involvement as parents want to shield their children from such experiences. Parents in this group scored high on the familismo scale. This is consistent with their status as immigrants, given that ties to cultural values tend to be lost over generations (Marsiglia, Miles, Dustman, & Sills, 2002). These parents reported lower levels of efficacy in discipline. This may be related to the fact that they are negotiating a new environment, so they may feel that they need to change their disciplinary approach. Mexican immigrant parents reported that they felt judged for having different parenting approaches and that they had to prove that they were good parents (Bermúdez et al., 2014). Membership into this parenting profile was predicted by social support. Hence, parents in this group reported high social support levels. Social support is key to the success of immigrants, as their networks function to support their adaptation to the United States by linking them to employment opportunities, needed resources, and providing emotional support (Ayón & Ghosn, 2013). Consistent with the ecodevelopmental framework, social support, which is an exosystem relationship, functions independently of children to support positive parenting among Latino immigrants. In this study, social support promoted a parenting style that was highly engaged with children and family values.

The second largest group of parents (17%) was classified as engaging in a child-centered parenting style. In this group, parents also had high involvement, monitoring, agency, and lower levels of discipline. This was the only group with low levels of familismo. These parents tended to be bicultural, as membership into this category was predicted by high Mexican and Anglo orientation. Highly acculturated parents have been found to value instilling individualism in children (Calzada et al., 2012). As it relates to the present study, parents who are bicultural may approach parenting from a more individualist framework; that is, while they feel connected to their Mexican identity, instilling family unity is not a critical element of their parenting.

The parents classified as having a moderate parenting style made up 15% of the participants. Similar to the family parenting profile, this group had high familismo with moderate levels of involvement, monitoring, and agency and higher levels of efficacy in disciplining. Disciplinarian parenting represented the smallest number of parents (3%). Compared to the other parenting profiles, parents who were classified as disciplinarian reported the lowest scores of involvement, monitoring, and agency; they had comparable scores in familismo to family parenting and moderate parenting, and they reported the highest levels of efficacy in disciplining. Membership into this group of parents was predicted by low Mexican and Anglo orientation. Low scores on the Mexican- and Anglo-orientation scales may have been due to lack of ethnic identity or clear ethnic identity. While these parents were less engaged with their children (i.e., lower scores in monitoring and involvement), they reported high efficacy in disciplining. Their interaction with children may be focused on discipline.

Family conflict may be a precursor to child problems (Pantin et al., 2003). In this study, child and family parenting were associated with less family conflict, while disciplinarian and moderate parenting were associated with more parent–child conflict. The major difference between these two subsets of parents was that disciplinarian and moderate parents were less engaged with children (i.e., lower scores in monitoring and involvement) and reported feeling more efficacious in disciplining children. Parents in the family and child-centered parenting styles reported less self-efficacy in disciplining, but were highly involved with their children. Being highly engaged with children may foster more positive intrafamilial interactions. Parents in the disciplinarian and moderate parenting styles may engage in harsher parenting. While they may feel efficacious in their disciplining, they may not engage with their children in positive ways, which can impact parent–child communication. Thus, these families experience more family conflict as they interact.

Implications

In order to support Latino immigrant parents and promote positive parenting strategies, practitioners need to engage families from a culturally grounded framework. A vast majority of the parents in this study reported highly endorsing familismo or strong family unity and ties, a critical cultural value for Latinos. This finding highlights that cultural values are inherent to parenting for many Latino immigrants; therefore, cultural influences should not be treated as secondary factors when assessing parenting. At the same time, acculturation status should be a key element in the assessment process for family practice with Latinos. In this study, there were differences in parenting styles by acculturation levels. Also, other studies document the impact of acculturative dissonance, or divergent acculturation statuses within families (Rumbaut & Portes, 2002). When children acculturate more quickly than their parents, there tend to be higher levels of stress and conflict between parents and youth (Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, 1994). Subsequently, family interventions have been framed around acculturation status. For example, the intervention Entre dos Mundos is focused on promoting biculturalism among children of immigrants, as children who are bicultural tend to have more positive outcomes compared to youth who assimilate into the mainstream culture (Smokowski & Bacallao, 2011). If cultural values and acculturation are not assessed for and taken into account when developing interventions, we may limit our opportunity to do optimal work with Latino families. Taking these factors into account is a necessary step in developing culturally informed and grounded interventions for Latino families.

Social support predicted membership into the family parenting style, which was associated with lower levels of family conflict. Family interventions that are culturally grounded and target Latino families should integrate building and identifying positive sources of social support. The protective effects of social support are well documented and supported in the present study and, therefore, should be a critical element in practice with Latino families.

Within the context of the ecodevelopmental framework, this study found that parenting styles among Latino immigrants were grounded in Latino cultural values (i.e., familismo) and influenced by social support and acculturation levels. Impacting the generalizability of findings, the participants of this study were engaged in family interventions, meaning their perceptions of and experiences with their children may be different from parents who did not participate in such interventions. Additionally, this study did not comprehensively capture all cultural elements relevant to Latino parenting. However, it did capture familismo, a core cultural value. By using this cultural element to classify parenting styles, Latino parenting was approached from a culturally grounded and informed framework. This study found a strong relationship between culturally grounded parenting and healthy interactions among family members. In turn, this has the potential to promote youths’ well-being and reduce the likelihood of involvement in risky behavior, such as drug use. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between culturally grounded parenting styles, family conflict, and risky behavior among youth.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE.

Cultural values, acculturation, and social support impact parenting practices for many Latino immigrants. These factors should be key elements in assessment plans and interventions for Latino families.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD/NIH), award P20 MD002316 (F. Marsiglia, P.I.).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMHD or NIH.

References

- Allen ML, Elliott MN, Fuligni AJ, Morales LS, Hambarsoomian K, Schuster MA. The relationship between Spanish language use and substance use behaviors among Latino youth: A social network approach. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, Becerra D. Latino immigrant families under siege: The impact of SB1070, discrimination, and economic crisis. Advances in Social Work. 2013;14:206–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ayón C, Bou Ghosn M. Latino immigrant families’ social support networks: Strengths and limitations during a time of stringent immigration legislation and economic insecurity. Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;41:359–377. [Google Scholar]

- Bacallao ML, Smokowski PR. Obstacles to getting ahead: How assimilation mechanisms impact undocumented Mexican immigrant families. Social Work in Public Health. 2013;28:1–20. doi: 10.1080/19371910903269687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Cultural, family, and personal contexts of parent-adolescent conflict. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1994;56:375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Prelow HM, Dumka LE, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Michaels ML, Tein J. Pathways from family economic conditions to adolescents’ distress: Supportive parenting, stressors outside the family, and deviant peers. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development. 1966;37:887–907. doi: 10.2307/1126611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez JM, Zak-Hunter L, Stinson MA, Abrams BA. “I am not going to lose my kids to the streets”: Meanings and experiences of motherhood among Mexican-origin women. Journal of Family Issues. 2014;35:3–27. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12462680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Huang KY, Anicama C, Fernandez Y, Miller Brotman L. Test of a cultural framework of parenting with Latino families of young children. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18:285–296. doi: 10.1037/a0028694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, Kennedy TM, Bregman A, Epstein-Ngo Q. Always aware (siempre pendiente): Latina mothers’ parenting in high-risk neighborhoods. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:805–815. doi: 10.1037/a0029584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Familias unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:113–132. doi: 10.1023/a:1015420503275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodriguez M, Donovick MR, Crowley SL. Parenting styles in a cultural context: Observations of “protective parenting” in first-generation Latinos. Family Process. 2009;48:195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Harvey EA, Driscoll P. Parent-centered parenting values among Latino immigrant mothers. Journal of Family Studies. 2009;15:296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller B, García Coll C. Learning from Latinos: Contexts, families, and child development in motion. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:559–565. doi: 10.1037/a0019412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Pachter LM. Ethnic and minority parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 4. Social conditions and applied parenting. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Psychology Press; 2002. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Coxe S, Roosa MW, White RM, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Saenz D. Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican–American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Dittus P, Jaccard J, Johansson M, Bouris A, Acosta N. Parenting practices among Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers. Social Work. 2007;52:17–30. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth LC, Ispa JM, Rudy D. Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development. 2006;77:1282–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children’s mental health: Low-income Mexican-American and Euro-American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74:189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo C, Weiss L, Shanahan T, Rodriguez-Brown F. Parental self-efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting practices and children’s socioemotional adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2000;20:197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Leidy MS, Guerra NG, Toro RI. Positive parenting, family cohesion, and child social competence among immigrant Latino families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:252–260. doi: 10.1037/a0019407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love JA, Buriel R. Language brokering, autonomy, parent-child bonding, biculturalism, and depression: A study of Mexican American adolescents from immigrant families. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2007;29:472–491. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In: Mussen PH, Hetherington EM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development. 4. New York, NY: Wiley; 1983. pp. 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Miles BW, Dustman P, Sills S. Ties that protect: An ecological perspective on Latino/a urban preadolescent drug use. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2002;11:191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Nagoshi J, Parsai MB, Booth J, Castro FG. The parent–child acculturation gap, parental monitoring, and substance use in Mexican heritage adolescents in Mexican neighborhoods of the Southwest U.S. Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;42:530–543. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Parsai M, Kulis S. Effects of familism, family cohesion and family adaptability on problem behaviors among adolescents in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2009;18:203–220. doi: 10.1080/15313200903070965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migration Policy Institute. State immigration data profiles. n.d Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/stateprofiles/state/demographics/US.

- Muthén B. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D, editor. Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 2004. pp. 345–367. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:267–316. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Eccles JS, Jacobs JE, Barber BL. Six paths to adulthood: Fast starters, parents without careers, educated partner, educated singles, working singles, and slow starters. In: Settersten RA Jr, Furstenberg FF Jr, Rumbaut RG, editors. On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 320–355. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Coltrane S, Duffy S, Buriel R, Dennis J, Powers J, Widaman KF. Economic stress, parenting, and child adjustment in Mexican American and European American families. Child Development. 2004;75:1632–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Cardona JR, Córdova D, Jr, Holtrop K, Villarruel FA, Wieling E. Shared ancestry, evolving stories: Similar and contrasting life experiences described by foreign born and U.S. born Latino parents. Family Process. 2008;47(2):157–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2008.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Coatsworth JD, Szapocznik J. Preventing substance abuse in Hispanic immigrant adolescents: An ecodevelopmental parent-centered approach. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science. 2003;25:469–500. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States, 2012. n.d Table 1 from Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project tabulations of 2000 Census (5% IPUMS) and 2012 American Community Survey (1% IPUMS). Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/2014/04/FINAL_Statistical-Portrait-of-Hispanics-in-the-United-States-2012.pdf.

- Prelow HM, Weaver SR, Bowman MA, Swenson RR. Predictors of parenting among economically disadvantaged Latina mothers: Mediating and moderating factors. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38:858–873. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Ruiz M. Does familism lead to increased parental monitoring? Protective factors for coping with risky behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG, Portes A. Ethnicities: Coming of age in immigrant America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marín BV, Perez-Stable EJ. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Coatsworth JD, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Beyond acculturation: An investigation of the relationship of familism and parenting to behavior problems in Hispanic youth. Family Process. 2012;51:470–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shears JK. Understanding differences in fathering activities across race and ethnicity. Journal of Early Childhood Research. 2007;5:245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Bacallao M. Becoming bicultural: Risk, resilience and Latino youth. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sotomayor-Peterson M, Figueredo AJ, Christensen DH, Taylor AR. Couples’ cultural values, shared parenting, and family emotional climate within Mexican American families. Family Process. 2012;51:218–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Unger JB, Knight GP, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Developmental trajectories of acculturation in Hispanic adolescents: Associations with family functioning and adolescent risk behavior. Child Development. 2013;84:1355–1372. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco M. The cultural psychology of Hispanic immigrants. In: Weaver T, editor. Handbook of Hispanic culture in the United States: Vol. 2. Anthropology. Houston, TX: Arte Publico Press; 1994. pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Urban Institute. Children of immigrants: Data tool. n.d Retrieved from http://datatool.urban.org/charts/datatool/pages.cfm.

- Varela RE, Vernberg EM, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Riveros A, Mitchell M, Mashunkashey J. Parenting style of Mexican, Mexican American, and Caucasian-non-Hispanic families: Social context and cultural influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:651–657. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]