Abstract

Objective

To assess predictors and moderators of a cognitive-behavioral prevention (CBP) program for adolescent offspring of parents with depression.

Method

This four-site randomized trial evaluated CBP compared to usual community care (UC) in 310 adolescents with familial (parental depression) and individual (youth history of depression or current subsyndromal symptoms) risk for depression. As reported by Garber et al., a significant prevention effect favored CBP through 9 months; however, outcomes of CBP and UC did not significantly differ when parents were depressed at baseline. The current paper expanded on these analyses and examined a range of demographic, clinical, and contextual characteristics of families as predictors and moderators and used recursive partitioning to construct a classification tree to organize clinical response subgroups.

Results

Depression onset was predicted by lower functioning (HR=0.95, 95% CI: 0.92-0.98) and higher hopelessness (hazard ratio [HR]=1.06, 95% CI: 1.01-1.11) in adolescents. The superior effect of CBP was diminished when parents were currently depressed at baseline (HR=6.38, 95% CI: 2.38-17.1) or had a history of hypomania (HR=67.5, 95% CI: 10.9-417.1), or when adolescents reported higher depressive symptoms (HR=1.04, 95% CI: 1.00-1.08), higher anxiety (HR=1.05, 95% CI: 1.01-1.08), higher hopelessness (HR=1.10, 95% CI: 1.01-1.20), or lower functioning (HR=0.94, 95% CI: 0.89-1.00) at baseline. Onset rates varied significantly by clinical response cluster (0% to 57%).

Conclusion

Depression in adolescents can be prevented, but programs may produce superior effects when timed at moments of relative wellness in high-risk families. Future programs may be enhanced by targeting modifiable negative clinical indicators of response.

Keywords: depression, prevention, adolescents, cognitive-behavioral therapy

Introduction

Depression is a highly prevalent, disabling, and recurrent disorder. Nearly a quarter of the population will experience clinically impairing depression,1 with half of onsets occurring in adolescence,2 conferring a high risk for chronic recurrence throughout the lifespan.3 Worldwide, depression has the third highest burden of disease of any ailment, and within higher-income countries, depression is the leading cause of disability.4,5 Efficacious interventions for depression have been developed, but meta-analytic evidence on treatment effects in youth and adulthood suggest that effects sizes are not large and that recent, more methodologically rigorous trials may produce smaller effects than historical estimates.6,7 Furthermore, both early onset and chronic course of depression have been associated with poorer treatment response.8 These sobering statistics have led to calls to designate the prevention of depression in adolescence a pressing public health priority and to encourage the dissemination of programs capable of serving a broad swath of those at risk.9

Evidence of the effectiveness of depression prevention has been mixed, with meta-analyses suggesting modest effects for universal prevention efforts but more promising outcomes for programs targeting high-risk youth.10 In this context, we launched the Prevention of Depression (POD)1 study, a multi-site randomized trial targeting adolescents at both familial and individual risk for depression. The POD trial built on the foundational cognitive-behavioral prevention program (CBP) of Clarke et al.,11, 12 who demonstrated significant prevention of depressive episodes with CBP compared to usual community care (UC) for adolescent offspring of parents with depression. The POD study extended this work (a) into a multi-site context to test the generalizability of effects, (b) through refining the Clarke CBP protocol to a smaller core of weekly sessions and a period of monthly booster sessions, and (c) by enriching the risk profile of the sample by requiring both familial history and individual risk (current high symptoms or history of a depressive disorder). Acute outcomes of POD were quite positive. CBP significantly separated from UC control in preventing onsets of depression, replicating the Clarke findings across the larger, multi-site sample,13 and the size of this effect was clinically comparable to the acute efficacy of antidepressant medication.

The depression prevention literature has continued to grow with additional evidence accumulating for specific CB interventions such as the Penn Resiliency Program,14 and recent findings suggesting there may be value in approaches drawing from Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depression.15, 16 Across this literature, the POD results represent the strongest depression prevention effects to date, but these encouraging findings are qualified by two factors. First, overall onset rates were high, even within CBP (21% onset rate). Second, the positive effects of CBP were significantly moderated by whether parents were in a depressive episode at the time that the adolescents commenced participation in the intervention. When parents were not depressed at baseline, CBP was particularly efficacious, strongly separating from the UC control condition (12% versus 41% onset rate). Conversely, when parents were actively depressed at baseline, the benefit of CBP was erased, and outcome in CBP and UC did not differ significantly (31% versus 24% onset rate).

In the current report, we sought to unpack these findings and identify demographic, clinical, and contextual predictors and moderators of acute response to CBP and to define cluster of responders and non-responders to the intervention. Given the breadth of this inquiry, we adopted a model-building approach, with a planned series of univariate tests leading to more complex multivariate models. We hypothesized that parental depression at baseline would emerge as a significant moderator of acute effects, even within this multivariate context.

Method

Participants

Participant characteristics and sampling procedures have been described in detail elsewhere13 and are summarized here. The current sample consisted of 310 adolescent (age 13 to 17) children of parents with depression. In addition to parental history of depression, adolescents were at risk for depression by presence of (a) current subsyndromal depressive symptoms (i.e., Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale [CES-D] > 20; n = 62 [20%]), (b) prior history of a DSM-IV depressive disorder (n = 170; 55%), or (c) both (n = 78; 25%). Exclusion criteria were lifetime bipolar I disorder or schizophrenia in parents or youth, a current DSM-IV mood disorder in the adolescent, or current taking of antidepressant medication for youth depression. Children of non-biological target parents were excluded from the current analyses (n = 6). In two-parent households where both parents endorsed a history of depression, a primary target parent was selected for assessment based on family preference. More than one sibling was allowed to participate; siblings were yoke randomized to the same intervention condition. There were 32 sets of siblings (one set of triplets).

The sample was recruited August 2003 through February 2006 evenly across four sites (Boston, MA; Nashville, TN; Pittsburgh, PA; Portland, OR). Sample retention did not differ across study arms or across sites (M = 90.5% retained).13 No significant differences were found on demographic, entry characteristics, or depression measures between retained participants and those who did not complete the follow-up.

Procedures

Design

Adolescents were randomized to CBP or UC using Begg and Iglewicz's17 modification of Efron's18 biased coin toss to balance cells on age, sex, race, and ethnicity, and inclusion criteria. Randomization was successful and intervention groups did not significantly differ on baseline parent, adolescent, or family characteristics, within or across sites. The study employed an intent-to-treat design, and all participants were considered part of the study from the point of randomization.

Intervention conditions

The Cognitive Behavioral Prevention (CBP) program was delivered to small groups of adolescents in eight weekly and six monthly (booster) sessions of 90 minutes each. Groups were led by a trained clinician with a master's or doctoral degree, and clinicians demonstrated high adherence (88% of content delivered). The principal focus of the program was on teaching cognitive restructuring skills for unrealistic and overly negative thoughts and problem-solving skills for stress management. Adolescents attended an average of 6.5 weekly and 3.8 monthly sessions. At weeks 1 and 8, there were informational meetings for parents, attended by 76.4% and 70.9% of adolescents' parents, respectively.

Usual Care (UC)

Families across both arms were permitted to initiate any mental health or other health care services after study entry over the course of the study. The UC condition was thus characterized by the absence of participation in CBP rather than by participation in specific alternate community services. As reported elsewhere, families in CBP and UC did not significantly differ in community service utilization during the follow-up window (e.g., 29.3% of UC versus 30.8% of CBP youth accessed outpatient mental health).

Assessments

In this report, data were drawn from assessment interviews conducted at baseline and nine months post-baseline (median = 42.1 weeks). 13 Assessments were performed by independent evaluators (IEs) masked to condition. IEs completed extensive training, participated in ongoing supervision, and demonstrated a minimum inter-rater reliability level of = 0.80 on diagnostic variables in two practice interviews before conducting study assessments.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Family information was collected by parent report; race/ethnicity was collected via self-report separately for parents and adolescents. Pubertal status was assessed with the adolescent Self-Rating Scale for Pubertal Development (PDS).19

Parental clinical characteristics at baseline

Index parents were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)20 to assess (a) current mood disorder diagnoses; (b) duration, number, and timing of prior mood disorder episodes; (c) current and past comorbid anxiety and substance use diagnoses; and (d) suicidal behaviors and attempts. Parents also completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale (CESD)21, a dimensional measure of depression severity (α = 0.93 in current sample).

Adolescent clinical characteristic at baselines

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-aged Children–Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL)22 is a semi-structured diagnostic interview combining parents' and adolescents' reports of youths' symptoms. The K-SADS-PL assessed baseline eligibility (no current mood diagnosis) and history of past depressive episodes. Adolescents also completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale for Adolescents (CES-DA)23 as a dimensional measure of depression severity, and the Hopelessness Scale (BHS)24 to assess pessimism about their future. To provide dimensional measures of other psychological symptoms, adolescents completed the Screen for Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED)25, the Aggression Questionnaire26, and the Disruptive Behavior Disorder Scale–Adolescent Report (DBDA)27, which provides separate ADHD and disruptive behavior scores. Reliability of dimensional measures was high (all α ≥ 0.85). Adolescent functional impairment was rated with the Children's Global Adjustment Scale (CGAS)28 with good reliability (ICC = 0.60).29

Contextual factors at baseline

Data also were gathered on adolescents' perceptions of family conflict (Conflict Behavior Questionnaire [CBQ])30 and parental acceptance, psychological control, and monitoring (Children's Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory [CRPBI])31. Internal consistency of total scores and subscales were high in this sample (all α ≥ 0.80). The Life Events Checklist (LEC)32 was completed by adolescents to produce a total life stress score, while past trauma exposure was obtained from the posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) section of the K-SADS and coded as present–absent for abuse (physical or sexual).

Depression outcome

At follow-up, parents and adolescents were interviewed with the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE)33, which provides a continuous assessment of adolescents' depressive symptoms and the onset/offset of depressive episodes. A score from 1 through 6 on the Depression Symptom Rating scale (DSR) was given for each week of the follow-up period. The outcome measure of the current study was an onset of a probable or definite major depression episode (MDE) defined by a DSR score of > 4 for at least two weeks. Inter-rater reliability was high (97.5% agreement) across the nine-month follow-up period.

Analytic Plan

Consistent with Kraemer et al.,34 predictors were defined analytically as baseline (pre-randomization) variables that had a main effect on outcome, regardless of intervention condition. Analyses of predictors proceeded in two steps. First, univariate Cox regression models were conducted to assess which of the candidate predictor variables were associated with MDE onset (equations included candidate predictor and the main effects of treatment). Second, to identify the most parsimonious set of predictors, a multivariate Cox regression with a backwards stepping procedure was used. All predictors significant at the first, univariate stage of analysis were entered into the model, and p values greater than 0.1 were the criteria for model removal.

A moderator was defined as a baseline variable that differentially predicted outcome across study conditions. Potential moderators were entered individually into Cox regression models that included the candidate variable, intervention (CBP vs. UC), and the interaction term. A significant intervention by candidate variable interaction indicated moderation. 34

As a secondary analysis, we sought to use these moderators to create clinical response clusters within CBP and UC. To accomplish this goal, we conducted recursive partitioning of the survival function to identify homogenous nodes of youth; that is, clusters of adolescents with similar risk of MDE over the follow-up period. Moderators identified in the first stage of analysis were used to partition the sample and create subgroup response “trees” within each condition (i.e., CBP, UC). Each significant moderator was examined one at a time at all possible cutoff points to produce nodes (i.e., clusters of youths) with the highest level of statistical purity. A perfectly pure node would consist of a group of adolescents where (a) all observations were censored, (b) all depressive episodes occurred at the same time, or (c) all episodes occurred at the same time followed by censored times.35 This process was repeated in a nested fashion, until reaching a terminal node of adolescents that (a) was perfectly pure, (b) had small sample sizes (N ≤ 20), or (c) for all observations there was the identical distribution of the candidate moderator variables, rendering further splitting impossible (e.g., if within a node, adolescents who experienced a depressive episode and those who did not had the same proportion of females, we would be unable to split the node further using sex as a candidate variable). In addition, for interpretability, we stopped further splitting of the sample if the procedure began identifying the same candidate moderator at multiple levels (e.g., repeatedly splitting on the same variable at different cut-points). STATA 9.0 was used to conduct the Cox regression analysis, and the rpart package in R was used for recursive partitioning. Cox models accounted for the correlation of siblings using the cluster option in Stata, which produces clustered robust standard errors. No such options were available for recursive partitioning methods and siblings were treated as independent observations for this analysis. Because of the exploratory, hypothesis-generating nature of these analyses, p ≤ .05 was considered to be statistically significant across analyses.

Results

Predictors (Across Both Intervention Conditions)

Neither parent nor adolescent demographic characteristics significantly predicted onset of a depressive episode during the follow-up period (see Tables 1 and 2). Parents' clinical characteristics also were not significantly associated with adolescent episode onset. Clinical features of adolescents, however, did emerge as significant predictors. Increased risk of MDE onset was associated with elevated symptoms of depression (CES-DA), high hopelessness (BHS), heightened aggression (AGQ), and lower functioning (CGAS) at baseline. In addition, contextual variables predicted episodes (see Table 2); higher conflict with parents at baseline (CBQ), higher levels of coercive parental psychological control (CRPBI control), lower levels of parental acceptance (CRPBI acceptance), and higher number of stressful life events in the year prior to study entry were associated with worse outcomes, across both CBP and UC.

Table 1. Parent Characteristics as Predictors of Outcome Across Cognitive-Behavioral Prevention (CBP) and Usual Community Care (UC).

| Candidate Predictor | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Parent demographic characteristics | ||

| Sex (n=301) | 0.92 (0.46-1.82) | .80 |

| Minority status (n=298) | 1.30 (0.70-2.50) | .44 |

| Hispanic background (n=298) | 1.00 (0.40-2.80) | .94 |

| Age (n=300) | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | .15 |

| Marital status (n=301) | 0.74 (0.48-1.15) | .18 |

| Socioeconomic status (n=300) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | .67 |

| Education beyond high school (n=301) | 0.88 (0.53-1.48) | .64 |

| Employed (n=300) | 0.88 (0.53-1.48) | .64 |

| Features of parental depression | ||

| CESD at baseline (n=298) | 1.02 (0.99-1.03) | .08 |

| Current parental depression at baseline (n=301) | 1.14 (0.74-1.77) | .55 |

| Age of onset of first MDD (n=292) | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | .79 |

| Lifetime duration of MDD episodes (n=286) | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | .42 |

| Lifetime duration of MDD and dysthymia (n=295) | 1.00 (0.99-1.00) | .21 |

| Lifetime number of MDD episodes (n=289) | 1.01 (0.97-1.04) | .68 |

| Comorbidity at baseline | ||

| Anxiety (n=295) | 0.98 (0.58-1.66) | .94 |

| Substance abuse (n=295) | 3.29 (0.91-11.80) | .07 |

| Substance dependence (n=295) | 2.18 (0.55-8.66) | .27 |

| Suicidal behavior (n=295) | 0.50 (0.07-3.50) | .49 |

| Comorbidity by history | ||

| Hypomania (n=295) | 2.71 (0.68-10.80) | .16 |

| Anxiety (n=295) | 1.08 (0.68-1.71) | .74 |

| Substance abuse (n=295) | 0.96 (0.49-1.90) | .92 |

| Substance dependence (n=295) | 0.72 (0.28-1.80) | .49 |

| Suicidal behavior (n=294) | 0.86 (0.49-1.53) | .61 |

| Suicide attempt (n=294) | 0.85 (0.42-1.71) | .65 |

NOTE: CESD = Center for Epidemiological Scale Depression; HR = hazard ratio; MDD = major depressive disorder.

Table 2. Adolescent Characteristics and Contextual Variables as Predictors of Outcome Across Cognitive-Behavioral Prevention (CBP) and Usual Community Care (UC).

| Candidate Predictor | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Adolescent demographic characteristics | ||

| Sex (n=301) | 1.06 (0.68-1.67) | .77 |

| Minority status (n=296) | 1.17 (0.64-2.12) | .61 |

| Hispanic background (n=300) | 0.86 (0.35-2.12) | .75 |

| Age (n=301) | 0.91 (0.78-1.05) | .20 |

| Pubertal status (n=297) | 0.93 (0.67-1.30) | .69 |

| Lives with target parent (n=296) | 0.48 (0.16-1.44) | .19 |

| Clinical characteristics at baseline | ||

| Prior history of depressive episode (n=301) | 1.08 (0.62-1.88) | .78 |

| Depression symptoms (CESDA; n=301) | 1.03 (1.01-1.05) | .004 |

| Hopelessness (BHS; n=297) | 1.08 (1.03-1.13) | .001 |

| Functioning (CGAS; n=301) | 0.94 (0.92-0.97) | .000 |

| Aggression (AQ; n=300) | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | .01 |

| Anxiety (SCARED; n=300) | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) | .12 |

| Disruptive behavior ADHD (DBDA; n=301) | 1.39 (0.88-2.20) | .16 |

| Disruptive behavior ODD/CD (DBDA; n=301) | 1.95 (0.95-4.00) | .07 |

| Contextual factors | ||

| Life events (n=294) | 1.04 (1.00-1.09) | .04 |

| Family conflict (CBQ, adolescent regarding parent; n=297) | 1.10 (1.01-1.20) | .03 |

| CRPBI acceptance subscale (n=297) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | .05 |

| CRPBI psychological control subscale (n=297) | 1.08 (1.03-1.15) | .004 |

| CRPBI parental monitoring subscale (n=297) | 0.92 (0.85-1.01) | .07 |

| Exposure to physical abuse (n=299) | 0.95 (0.35-2.59) | .93 |

| Exposure to sexual abuse (n=299) | 1.09 (0.49-2.43) | .83 |

NOTE: ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; AQ = Aggression Questionnaire; BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale; CBQ = Conflict Behavior Questionnaire; CESDA = Center for Epidemiological Scale Depression–Adolescents; CGAS = Children's Global Assessment Scale; CRPBI = Child Report of Parent Behavior Inventory; DBDA = Disruptive Behavior Disorder Scale–Adolescent; HR = hazard ratio; ODD/CD = oppositional defiant and conduct disorders; SCARED = Screen for Anxiety and Related Emotional Disorders.

In the multivariate model, the most parsimonious predictors were higher hopelessness (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.01-1.11, p = .02) and lower functioning on the CGAS (HR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.92-0.98, p < .001) in the adolescent. With all significant predictors included in the multivariate Cox model, the effect of intervention was marginally significant (HR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.41-1.03, p = .07), and the magnitude and direction of the hazard ratio was comparable to the main effect of the intervention in unadjusted analyses.

Moderators (Differential Prediction of Outcome Across Conditions)

Both parent and adolescent clinical characteristics negatively moderated the effects of CBP (see Table 3). In terms of parent characteristics, current depression (MDD or dysthymia) and history of hypomania were significant moderators (note that the base rate of hypomania in the sample was very low [n = 6]). For adolescents, higher depressive symptoms (CES-DA), higher anxiety symptoms (SCARED), lower functioning (CGAS), and higher hopelessness (BHS) moderated the effects of the CBP intervention on MDEs. Effects of these clinical variables within CBP and UC conditions were further explored through the creation of group-specific clinical response clusters.

Table 3. Significant Univariate Moderators of Response.

| Candidate Moderator | Main Effect | Intervention | Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Clinical characteristics of parents | ||||||

| Current parental depression at baseline | 0.55 (0.31-0.99) | .05 | 0.22 (0.10-0.48) | .000 | 6.38 (2.38-17.1) | .000 |

| History of hypomania | 1.45 (0.30-7.09) | .64 | 0.60 (0.38-0.95) | .03 | 67.5 (10.9-417.1) | .000 |

| Clinical characteristics of adolescents | ||||||

| Depression symptoms (CESDA) | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) | .34 | 0.30 (0.13-0.73) | .01 | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | .05 |

| Hopelessness (BHS) | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) | .31 | 0.37 (0.18-0.75) | .01 | 1.10 (1.01-1.20) | .02 |

| Anxiety symptoms (SCARED) | 0.99 (0.97-1.02) | .53 | 0.20 (0.08-0.51) | .001 | 1.05 (1.01-1.08) | .005 |

| Functioning (CGAS) | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | .02 | 41.9 (0.62-2832) | .08 | 0.94 (0.89-1.00) | .05 |

NOTE: BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale; CEDSA = Center for Epidemiological Scale Depression for Adolescents; CGAS = Children's Global Assessment Scale; HR = hazard ratio; SCARED = Screen for Anxiety and Related Emotional Disorders.

Clinical Response Clusters

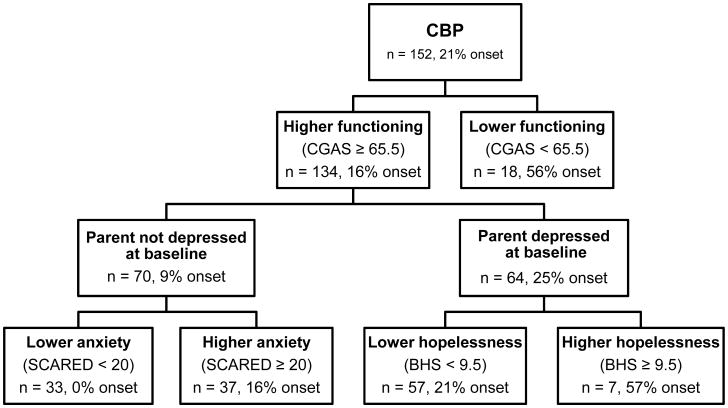

We next conducted recursive partitioning of the survival function within the CBP condition, using the six univariate moderators as classification factors. In this analysis, adolescents' functioning emerged at the top level of the response tree and was the most substantial predictor of onset of MDE over follow-up. As seen in Figure 1, 56% of lower- functioning adolescents (CGAS < 65.5) had a depressive episode during the follow-up compared to just 16% of higher-functioning youths. The low-functioning node of adolescents was unable to be subdivided further and was a terminal node in the CBP tree. Higher-functioning adolescents could be further split by current parental depression status and, within parental status, by youths' level of anxiety symptoms and hopelessness. The classification process ceased after these divisions and yielded a total of five terminal nodes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Classification tree for participants in the cognitive-behavioral prevention (CBP) program. Note: BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale; CGAS = Children's Global Assessment Scale; SCARED = Screen for Anxiety and Related Emotional Disorders.

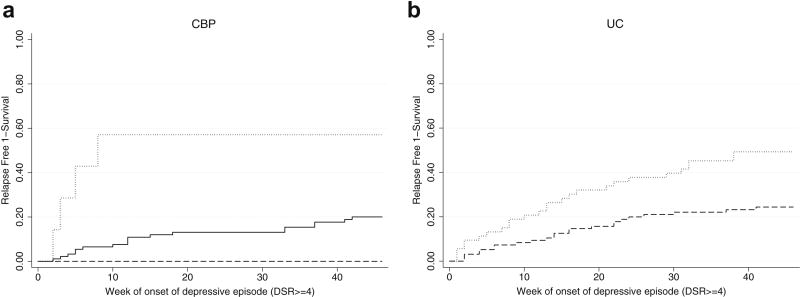

We tested for significant differences in survival between these five nodes, and three significant clusters of response were identified (see Figure 2). The lowest risk node (Group 1) was defined by higher functioning, the absence of current parental depression at baseline, and lower anxiety. Compared to Group 1, all other nodes were at significantly higher risk (all p < .001); precise hazard ratios could not be calculated for these pair-wise comparisons, however, due to the absence of any depressive episode onsets in Group 1 (leading to an HR denominator of zero).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for terminal node groupings within (a) cognitive-behavioral prevention (CBP) and (b) usual community care (UC). Note: Within CBP, the blue line represents lowest risk, the green line moderate risk, and the red line the highest risk group. Within UC, the red line is the higher risk group and the blue line is the lower risk group. All survival curves significantly differed within condition. DSR = Depression Symptom Rating scale.

The next highest-risk node (Group 2) was characterized by higher functioning, no parental depression, and higher anxiety. This cluster of adolescents did not differ significantly from Group 3 – the node of youths with higher functioning, current parental depression at baseline, and lower hopelessness (HR = 1.40; 95% CI, 0.50-3.70; p = .50). The final two nodes both had very high rates of onset (56% and 57%, respectively). These highest-risk nodes were characterized by either the combination of higher functioning paired with current parental depression at baseline and higher adolescent hopelessness (Group 4) or overall lower functioning (Group 5). These nodes did not differ from each other (HR = 1.1; 95% CI, 0.3-4.6; p = .87), but they each did significantly diverge from Groups 1, 2, and 3. Based on these analyses, we clustered adolescents into three categories of lowest risk (Group 1), moderate risk (Groups 2 and 3), or highest risk (Groups 4 and 5).

We next repeated this procedure within the UC condition to probe for clusters of response, using the same set of six variables. This process yielded two factors; adolescent functioning at the highest level of the tree and youth baseline depression symptom level nested within functioning. Survival analysis of these four terminal nodes suggested that a single split on the CGAS produced a sufficient model of the data, without use of depression symptom level. There was no significant difference between the two lower-functioning nodes (HR = 2.0; 95% CI, 0.7-5.6; p =.19) or between the two higher-functioning groups (HR= 1.8; 95%, CI 0.8-4.0; p = .13). Overall, there was a significant difference between the lower and higher CGAS groups (HR= 2.4; 95% CI, 1.4-4.2; p = .002). Accordingly, we trimmed the UC classification tree to only one level, with a higher functioning/lower risk cluster (24% MDE onsets) and a lower functioning/higher risk cluster (49% MDE onsets). Survival curves for these two response clusters within UC are displayed in Figure 2 (panel b).

Note that although functioning appeared within both the UC and CBP groups as an important classification variable, the cut-points on the CGAS derived from the recursive partitioning process were different in the two conditions. In the UC group, “high functioning” was defined by a CGAS score ≥ 72.5, which corresponds to slight impairment and transient difficulties in functioning. In contrast, the cut-point for higher functioning in CBP was ≥ 65.5, which corresponds to some difficulties functioning in a single area. Thus, consistent with the univariate moderator analyses (Table 3), the relation between functioning and outcome varied by condition.

Discussion

In the POD trial, adolescents were selected to be at risk for the development of depression on the basis of individual risk and family history. Although all youths shared a common family risk factor (i.e., parent history of depression), parents' depression status at the time of study entry was a potent moderator of effects. As reported previously,13 if parents were not in episode at the time of the baseline assessment, youths in CBP had significantly fewer depressive episodes than those in the UC control condition. No significant group difference was found, however, if the parent was actively depressed when their child entered the trial. The current report further explored the variability in intervention response by identifying key predictors and moderators of effects and defined clinical response clusters within this high-risk sample.

Two adolescent clinical characteristics emerged as significant predictors in multivariate analyses: higher hopelessness and lower functioning were associated with poor outcomes in both CBP and UC. In addition, six clinical features of adolescents and parents were identified as significant univariate moderators. The superior effect of CBP relative to UC was diminished when parents were currently depressed at baseline or had a history of hypomania, or when adolescents reported higher depressive symptoms, higher anxiety, higher hopelessness, or lower functioning. Rather than attempting to test and interpret a seven-variable interaction model (i.e., six moderators x condition), we used these six characteristics as classification factors to partition the sample into clinically meaningful response subgroups. Recursive partitioning of the survival function was used to define statistically homogenous clusters of adolescents with a similar risk of depression onset. This method allowed us to organize the relations among these clinical features of families into a hierarchical classification tree structure.

Within CBP, the three clinical response clusters were defined by the combination of the adolescent's level of functioning, anxiety symptoms, hopelessness, and whether the parent was currently depressed at baseline. Of these characteristics, adolescent functioning was the most powerful, entering the classification tree at the first level and solely defining the worst response/highest risk cluster. Parental depression at baseline remained an important factor in understanding variability in response but operated in concert with youth anxiety and hopelessness within the classification structure. Within UC, only adolescent functioning emerged as a classification factor versus the richer array of clinical variables implicated in CBP response. This finding of greater richness within the CBP group parallels results from the large Multimodal Treatment Study for ADHD, where all of the “action” in defining response subgroups was within the best performing intervention conditions.36 Conceptually, this is likely to be the case, as control groups may represent the natural course of a disorder (onset of depression in a high-risk sample) and intervention conditions contain both this underlying process and additional variability in outcomes from the effect of the successful intervention. Interestingly, the cut point on the CGAS varied across conditions. In the UC group, relatively higher functioning was needed to see positive response as compared to a lower cut point in CBP, perhaps suggesting CBP worked to buffer the generally poor prognostic effects of functioning for youths between these thresholds.

In general, effects of depression prevention programs have been found to be stronger in higher-risk selected and indicated versus universal samples, and in demographic groups with higher base rates of depression onsets (e.g., females and older youths).37 In contrast, studies of the treatment of adolescent depression have shown that, across intervention conditions, poorer outcomes are predicted for older youths with more severe indicators of depression, higher levels of comorbid problems, and greater levels of environmental adversity.38 Studies of moderators of treatment response have been sparse but have found that maternal depression, interpersonal trauma, family conflict, and substance use appear to negatively moderate CB treatment effects.39 Effects for anxiety and negative cognitions, such as hopelessness, have been mixed, with enhanced effects of CB relative to control in some studies and diminished outcomes for CB found in other investigations.39

Results of the current report parallel findings from the treatment literature. Teens who were hopeful and functioning well had the best overall prognosis. Further, CBP was especially effective in preventing depression onset (relative to UC) when youths and families were at a time of relative wellness—parents not currently depressed and teens functioning well with lower anxiety and greater hope for the future. In these families, CBP may have operated as a capitalization model, building on participants' strengths to enhance coping skills and inoculate them against the development of depression over follow-up.

Clinically, this pattern of effects has both positive and negative implications. First, there is a clear indication for the use of CBP in at-risk families when they are clinically stable. Second, it is promising that all of the negative prognostic indicators and significant moderators were potentially modifiable; no demographic factors or historical characteristics (e.g., trauma history, history of past onsets) were associated with response. The negative implication of these findings, however, is that the version of the CBP intervention used in this trial may be less indicated when families are in the most distress.

Further research aimed at understanding the mediators underlying differences in outcome between these subgroups would provide useful guidance for additional program development. Across a broad range of studies, parental depression has emerged as a negative treatment indicator,36 and treatment of parental depression has begun to be associated with positive changes in youth outcomes.40 However, the mechanism underlying these effects is unknown. It may be that teens have a particularly hard time learning and applying cognitive skills when they are “under load”—actively coping with the stress of significant psychopathology (in themselves and parents) and struggling to maintain their daily responsibilities. Some evidence in the youth depression treatment literature indicates that the positive effect of CBT on problem-solving skills may be uncoupled in the presence of maternal depression.41 This would suggest a need to ameliorate these interfering conditions prior to participation (e.g., treating parents' depression). Parental depression and greater clinical impairment in adolescents also may interfere with treatment attendance or homework compliance, indicating a need to increase exposure to the active elements of the existing CB program. Alternatively, the central focus on cognitive change in the POD CB protocol may be too narrow for some multi-problem youth; other prevention models, such as those based on Interpersonal Psychotherapy, also have shown promise in recent trials.15, 16 A wider set of skills may be necessary for adolescents (e.g., reducing anxiety) and parents (e.g., warm and consistent parenting)42 to affect significant change and bring the benefits of depression prevention to the broader population of youth at risk for depressive disorders.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants (R01MH064735; R01MH64541; R01MH64503; R01MH64717) and by the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 RR024975-01), now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIMH or the National Institutes of Health.

Ms. Porta and Dr. Iyengar served as the statistical experts for this research.

The authors thank the adolescents and parents for their participation in this research.

Dr. Weersing has received research support from NIMH. Dr. Garber has received research support from NIMH and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Dr. Clarke has received research support from NIMH and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Beardslee has received grant funding from the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation and has served as a consultant to research projects, government agencies, and non-profit groups. Dr. Gladstone has received research support from NIMH, the Hull and East Yorkshire (HEY) Hospitals National Health Service Trust, the MetroWest Health Foundation, and Baer Prevention Initiatives. Dr. Lynch has received research support from NIMH. Dr. Brent has received research support from NIMH; has received royalties from Guilford Press; and has served as UpToDate Psychiatry Editor.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Drs. Shamseddeen, Hollon, Iyengar, and Ms. Porta report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. V. Robin Weersing, Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, San Diego State University and University of California, San Diego

Dr. Wael Shamseddeen, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Drs. Garber and Hollon are with Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN

Dr. Judy Garber, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN

Dr. Steven D. Hollon, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN

Dr. Gregory N. Clarke, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, OR

Dr. William R. Beardslee, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston

Dr. Tracy R. Gladstone, Wellesley Centers for Women, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA

Dr. Frances L. Lynch, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, OR

Ms. Giovanna Porta, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh

Dr. Satish Iyengar, University of Pittsburgh

Dr. David A. Brent, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh; University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Wai TC, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avenevoli S, Knight E, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Epidemiology of depression in children and adolescents. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Depression. World Health Organization; [Accessed May 10, 2014]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/. Published October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnsen TJ, Friborg O. The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy as an anti-depressive treatment is falling: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2015;141:747–768. doi: 10.1037/bul0000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein DN, Schatzberg AF, McCullough JP, et al. Age of onset in chronic major depression: relation to demographic and clinical variables, family history, and treatment response. J Affect Disord. 1999;55:149–57. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Research Council and Institute of Medicine Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices, and the Healthy Development of Children. Depression in Parents, Parenting, and Children: Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment, and Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merry SN, Hetrick SE, Cox GR, Brudevold-Iversen T, Bir JJ, McDowell H. Psychological and educational interventions for preventing depression in children and adolescents (Review) Evid Based Child Health. 2012;7:1409–1685. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003380.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke GN, Hawkins W, Murphy M, Sheeber LB, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in an at-risk sample of high school adolescents: A randomized trial of group cognitive intervention. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(3):312–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke GN, Hornbrook C, Lynch F, et al. A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention for preventing depression in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1127–34. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garber J, Clarke GN, Weersing VR, et al. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:2215–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunwasser SM, Gillham JE, Kim ES. A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program's effect on depressive symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:1042–54. doi: 10.1037/a0017671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young JF, Mufson L, Gallop R. Preventing depression: A randomized trial of Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Adolescent Skills Training. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:426–433. doi: 10.1002/da.20664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horowitz JL, Garber J, Ciesla JA, Young JF, Mufson L. Prevention of depressive symptoms in adolescents: A randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal prevention programs. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:693–706. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Begg CB, Iglewicz B. A treatment allocation procedure for sequential clinical trials. Biometrics. 1980;36:81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efron B. Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika. 1971;58:403–17. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carskadon MA, Acebo C. A self-administered rating scale for pubertal development. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14:190–195. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders -Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) Version 2.0. New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent DA, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, Trexler L. The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42:861–865. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545–53. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:452–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva RR, Alpert M, Pouget E, et al. A rating scale for disruptive behavior disorders, based on the DSM-IV item pool. Psychiatr Q. 2005;76:327–339. doi: 10.1007/s11126-005-4966-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, et al. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psych. 1983;40:1228. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robin AL, Weiss JG. Criterion-related validity of behavioral and self-report measure of problem-solving communication skills in distressed and nondistressed parent-adolescent dyads. J Behav Assess. 1980;2:339–352. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schludermann EH, Schludermann SM. Children's Report on Parent Behavior (CRPBI-108, CRPBI-30) for older children and adolescents. Winnipeg, MB, Canada: University of Manitoba; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson JH, McCutcheon SM. Assessing life stress in older children and adolescents: Preliminary findings with the Life Events Checklist. In: Sarason IG, Spielberger CD, editors. Stress and anxiety. Washington, DC: Hemisphere; 1980. pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, et al. The longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psych. 1987;44:540–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraemer HC, Wilson T, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psych. 2002;59:877–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, Singer B. Recursive partitioning in the health sciences. New Haven, CT: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Owens EB, Hinshaw SP, Kraemer HC, et al. Which treatment for whom for ADHD? Moderators of treatment response in the MTA. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:540–52. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:486–503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do M, Schwartz KG, Bolano C. Evidence-base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1220310. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weersing VR, Schwartz KTG, Bolano C. Moderators and mediators of treatments for youth with depression. In: Maric M, Prins PJM, Ollendick TH, editors. Moderators and Mediators of Youth Treatment Outcomes. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 65–96. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, et al. Remission of maternal depression is associated with reductions in psychopathology in their children: A STAR*D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dietz L, Marshal MP, Burton CM, et al. Social problem solving among depressed adolescents is enhanced by structured psychotherapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:202–11. doi: 10.1037/a0035718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Compas BE, Forehand R, Keller G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family cognitive-behavioral preventive intervention for children of depressed parents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:1007–20. doi: 10.1037/a0016930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]