Abstract

Objective

To assess the safety profile of ferumoxytol as an intravenous magnetic resonance (MR) imaging contrast agent in children.

Materials and Methods

We prospectively evaluated the safety of ferumoxytol administrations as an “off-label” contrast agent for MR imaging in non-randomized phase IV clinical trials at two centers. From September 2009 to February 2015 49 pediatric patients (21 female and 28 male, 5-18 years old) and 19 young adults (8 female and 11 male, 18-25 years old) were reported under an investigator-initiated investigational new drug (IND) investigation with institutional review board (IRB) approval, in health insurance portability and accountability act (HIPAA) compliance, and after written informed consent of the child's legal representative or the competent adult patient was obtained. Patients received either a single dose (5 mg Fe/kg) or up to 4 doses of ferumoxytol (0.7-4 mg Fe/kg) intravenously, which were approximately equivalent to 1/3 of the dose for anemia treatment. We monitored vital signs and adverse events directly for up to one hour post injection. In addition, we examined weekly vitals, hematologic, renal and liver serum panels for one month after injection in over 20 pediatric patients. At fixed time points before and after ferumoxytol injection data were evaluated for significant differences by a repeated measures linear mixed model.

Results

Four mild adverse events, thought to be related to ferumoxytol, were observed within one hour of 85 ferumoxytol injections: Two episodes of mild hypotension and one case of nausea in 65 injections in pediatric patients without related clinical symptoms. One young adult patient developed warmness and erythema at the injection site. All adverse events were self-resolving. No spontaneous serious adverse events were reported. At a dose of 5 mg Fe/kg or lower, intravenous ferumoxytol injection had no clinical relevance or statistically significant effect (p>0.05) on vital signs, hematological parameters, kidney function or liver enzymes within one month of the injection.

Conclusion

Ferumoxytol was overall well tolerated among 49 pediatric and 19 young adult patients suffering from various tumors or kidney transplants without major adverse events or signs of hematologic and kidney impairment or liver toxicity. Larger studies are needed to determine the incidence of anaphylactic reactions.

Keywords: Ferumoxytol, contrast media, ferric compounds, pediatric, safety, adverse events/ adverse effects, toxicity

Introduction

Ferumoxytol is an iron supplement approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (1), the European Medicines Agency in Europe (2), and in other countries around the world. It is composed of ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles which can be used as an “off-label” contrast agent for magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (3-6). In fact, the first intention of development for ferumoxytol was as a MR contrast agent (7). However, ferumoxytol is not approved for MR Imaging, clear dose-related efficacy studies are lacking and therefore potential indications and use of this agent must be evaluated carefully. Yet, ferumoxytol may overcome a number of limitations associated with standard gadolinium-based MR contrast agents, namely a short time window for vascular imaging, non-specific tissue enhancement, risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) and central nervous system (CNS) deposition (8, 9). The large size of ferumoxytol nanoparticles leads to long lasting blood pool enhancement, which can be used for MR angiography (10, 11), assessment of tumor blood volume and perfusion (12), and radiation-free whole body tumor staging (3). This opens a potential new field of imaging possibilities currently not available with classic gadolinium-based contrast agents. Ferumoxytol is phagocytosed primarily by macrophages, allowing improved in vivo characterization of tumors and inflammation through macrophage detection (5, 7). Ferumoxytol is taken up by the reticuloendothelial system, i.e. liver, spleen and bone marrow and can last several months in the liver where it is metabolized as iron for the normal blood iron pool (13, 14). Several studies showed that ferumoxytol was generally well tolerated in adult patients with chronic kidney diseases (CKD) (1, 15-17). Ferumoxytol has a carboxymethyl dextran coat, designed to decrease immunogenicity but sustain iron delivery (13, 18). However, recent reports of severe adverse events have caused concerns regarding the safety of ferumoxytol (19). Since the approval of ferumoxytol in 2009 and after more than 1.1 million distributed vials, 79 cases of anaphylactic reactions have been documented, with 18 of these being fatal (19). As a result, the FDA issued a boxed warning in March 2015 about the risk of serious, potentially fatal hypersensitivity reactions (19).

Safety data of ferumoxytol in children is very limited. Hassen and colleagues reported that ferumoxytol was overall well tolerated in six pediatric patients with gastrointestinal disorders except for one case of mild pruritus (20). Klenk and colleagues found no objective or subjective adverse events in 22 patients (3) and neither did Thompson and colleagues in seven patients (4). Ferumoxytol may be a good alternative to classic gadolinium-based contrast agents in children with impaired renal function. More importantly, its unique imaging features provide valuable diagnostic information, which are not attainable with gadolinium-based agents (4, 6, 11).

The purpose of our study was to report the safety profile of ferumoxytol as an “off-label” intravenous MR imaging contrast agent in children by evaluating vital signs as well as hematological, renal and liver laboratory tests before and after ferumoxytol administration in 49 pediatric and 19 young adult patients through an investigator-initiated investigational new drug investigation.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We evaluated the safety data of 49 children and 20 young adults who were enrolled in prospective, non-randomized phase IV clinical trials at two centers. The trials were approved by the Administrative Panel for the Protection of Human Subjects of the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of both institutions, HIPAA compliant, and were performed under an investigator initiated IND after written informed consent was obtained from the child's legal representative or the competent adult patient. For 29 out of the 49 pediatric patients some of the imaging findings have been previously published whereas none of the young adult patient data were published yet (3, 4). The prior articles investigated the imaging properties whereas in this manuscript we report the safety profile of ferumoxytol. Inclusion criteria were patients of any sex and race, age 5 to 18 years for children and, in accordance with the United States Department of Health and Human Services, 18 to 25 years for young adults (21) with planned ferumoxytol injection (Feraheme™ Injection, AMAG Pharmaceuticals, Waltham, MA) for MR imaging of tumors or inflammations. Exclusion criteria were comprised of patients with hemosiderosis/hemochromatosis, history of allergies to contrast agents, allergies to iron compounds or severe allergies to other substances, claustrophobia, and MR-incompatible metal implants. Patient history and clinical laboratory values were assessed for evaluating hemosiderosis/hemochromatosis.

Between September 2009 and February 2015 we enrolled 49 pediatric patients, including 21 girls (mean age: 12.5±2.8 years; median: 12.6 years) and 28 boys (mean age: 13.2±3.4 years; median: 14.6 years). We also enrolled 20 young adult patients, including 9 females (mean age: 21.7±5.6 years; median: 19.7 years) and 11 males (mean age: 20.3±2.3 years; median: 19.2 years). One young female adult patient withdrew from the study due to scheduling conflict, and was excluded from the study. Demographics and total ferumoxytol dose of the participants are shown in Table 1. A total of 85 doses of ferumoxytol were administered intravenously (65 in pediatric patients, 20 in young adults), with different concentrations, depending on the disease and study protocol. Thirty-eight pediatric and 18 young adult patients at Stanford received a single dose (5 mg Fe/kg) of undiluted ferumoxytol (30 mg Fe/mL), injected over 10–15 minutes. One young adult patient received two undiluted ferumoxytol injections with a dose of 5 mg Fe/kg 9 months apart. Eleven patients at OHSU received a single dose (n = 5) or 2–4 doses (n = 6; interval at least 3 months) of 1:1 saline diluted ferumoxytol (0.7–4 mg Fe/kg) at an infusion rate of 1.5 to 3 mL/s. Of note, the FDA meanwhile recommended an infusion of diluted ferumoxytol over 15 minutes. Patient ferumoxytol dosages ranged from 30 mg to 754.5 mg with a mean of 222.7 mg and a median of 207.0 mg for the pediatric patients and a mean of 347.9 mg and a median of 354.3 mg for young adults across the study. In seven patients (age < 10 years), ferumoxytol was administered while the patients were sedated with propofol (Diprivan™, AstraZeneca, Wilmington, DE) by a pediatric anesthesiologist. Sixty-one pediatric and four young adult patients underwent MRI directly after the ferumoxytol injection, eight pediatric and three young adult patients underwent MRI 24 hours after ferumoxytol injection (p.i.), five pediatric and four young adult patients underwent MRI immediately and within 48 hours p.i. and nine young adult patients underwent MRI up to seven days after the injection. At follow up imaging appointments, patients were again asked about any side effects encountered since the administration of the agent. The ferumoxytol administration was performed outside of the MR scanner in 38 children and 19 young adult patients and inside the MR scanner in 11 pediatric patients. The MRI was started within 5 minutes after completion of the ferumoxytol injection under continuous monitoring of vital signs except for 8 pediatric and 3 young adult patients, who started MRI 24 hours after injection.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients

| Center A | Center B | |

|---|---|---|

| Pediatrics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| Young children (≤10) | 4 | 6 |

| Adolescents (>10, ≤18) | 34 | 5 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 22 | 6 |

| Female | 16 | 5 |

| Race | ||

| White | 31 | 10 |

| African American | 1 | 0 |

| Asian | 2 | 0 |

| Others | 3 | 0 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 |

| Weight (Mean, Median) (kg) | ||

| Male | 58.8; 49.6 | 50.2; 44.5 |

| Female | 46.3; 37.4 | 30.2; 30.0 |

| Total Ferumoxytol Dose (Mean, Median) (mg) | ||

| Male | 293.6; 246.5 | 63.9; 60.3 |

| Female | 231.3; 186.8 | 72.4; 66.0 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Lymphoma/Leukemia/LPD* | 21 | 0 |

| Soft tissue sarcoma/tumor | 5 | 0 |

| Osteomyelitis | 4 | 0 |

| Renal transplant | 7 | 0 |

| CNS tumor | 0 | 11 |

| Others | 1 | 0 |

| Young Adults | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 11 | 0 |

| Female | 8 | 0 |

| Race | ||

| White | 17 | 0 |

| African American | 0 | 0 |

| Asian | 2 | 0 |

| Others | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 |

| Weight (Mean, Median) (kg) | ||

| Male | 76.0; 77.2 | - |

| Female | 66.6; 65.2 | - |

| Ferumoxytol Dose per Bodyweigt (Mean, Median) (mg) | ||

| Male | 352.2; 366.0 | - |

| Female | 341.4; 335.8 | - |

| Daignosis | ||

| Lymphoma/Leukemia/LPD | 6 | 0 |

| Soft tissue sarcoma/tumor | 4 | 0 |

| Osteomyelitis | 0 | 0 |

| Renal transplant | 9 | 0 |

| CNS tumor | 0 | 0 |

LPD: Lymphoproliferative disorders, CNS= Central Nervous System

Adverse Events

All patients underwent a medical exam as part of their routine clinical workup within one week before ferumoxytol administration. Preexisting conditions and any changes after ferumoxytol administration were recorded. We monitored the injection site for paravasation, rashes or hives. In addition, we interviewed the patients and their parents regarding any subjective adverse events before, during and after ferumoxytol administration. All adverse events were noted on case report forms. Adverse events were rated in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.03 from grade 1 “mild” through grade 5 “death” (22).

Vital Signs

Patients were observed and vital signs, including heart rate (HR) and blood pressure, were obtained immediately before, 15, 30, 45 and 60 minutes after ferumoxytol injection, and during subsequent MR scanning. The vital signs from the patients under sedation were continuously monitored until the sedation was terminated. The patients that underwent an MRI under sedation received continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring before and up to 60 minutes after the ferumoxytol administration. No significant changes in the ECG were noted in these patients. If abnormal vital signs were recorded after ferumoxytol injection, these were monitored until they returned to normal baseline values. Heart rate was measured either manually through radial pulse or using an automatic monitor. Blood pressure was measured either manually using a sphygmomanometer or using an automatic monitor. Hypotension was defined as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) for young children (age 5-10 years) < (70 + 2 × age in years) mmHg and < 90 mmHg for older children (age 10-18 years) and young adults (age 18-25) (23). Changes in blood pressure were considered clinically significant if there was >10 mmHg decrease compared to the SBP before injection. Normal ranges of HR were defined as 60-140 beats per minute (bpm) for young children (age 5-10 years) and 60-100 bpm for older children and young adults (24).

Hematology

Thirty-one pediatric patients received weekly complete blood counts (CBC) as part of their management of cancer or other diseases. CBCs reported were collected between 7 days before and up to 35 days after ferumoxytol injection. Eight pediatric patients received one or more red blood cell (RBC) transfusions during the study period and were consequently excluded from the evaluation. Therefore, changes of hemoglobin (Hgb), hematocrit (Hct) and RBC counts were evaluated for 26 injections administered in 23 pediatric patients. None of the patients were treated with other iron supplements. Of 23 pediatric who underwent follow up evaluation of Hgb, Hct and RBC, 12 pediatric patients were anemic and 11 pediatric patients were not anemic prior to ferumoxytol injection. Anemia in pediatric patients was defined as a Hgb concentration of more than 2 standard deviations below the mean of the reference population: Hgb < 11.5 g/dL for young children (age 5-12 years), Hgb <12.0 g/dL for older female (age <12 years) or Hgb <13.0 g/dL for older male (age <12 years) (25). The blood samples were analyzed at the clinical laboratories of each institution.

Renal and Liver Parameters

Renal and liver parameters were assessed using serum markers, including creatinine in 33 pediatric patients, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) in 19 pediatric patients, alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) in 27 pediatric patients. The laboratory values were collected and analyzed as described for hematological panels above. The normal reference ranges were defined as <1.2 mg/dL for creatinine, between 5 and 25 mg/dL for BUN, <40 U/L for AST, and <60 U/L for ALT.

Data Analysis and Statistics

The data were analyzed using repeated measures linear mixed models, with the patient as the random factor. Vital signs were modeled with fixed effects of age (≤10 versus >10 years), institution, sedation, time, and the interaction effect of sedation over time (sedation × time); laboratory measures were modeled with fixed linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time only. The same was done in the group of young adult patients. Equivalence for measurements over time was demonstrated by showing that the model mean and its 90% Confidence interval could fit within the predefined normal reference range at each time point (from 15 minutes before injection to 60 minutes after the injection in the case of SBP, DBP, and HR; from 7 days before the injection to 35 days after in the case of hemoglobin, renal and liver toxicity measures). All tests were two-sided with an alpha level of 0.05. All analyses were performed in SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

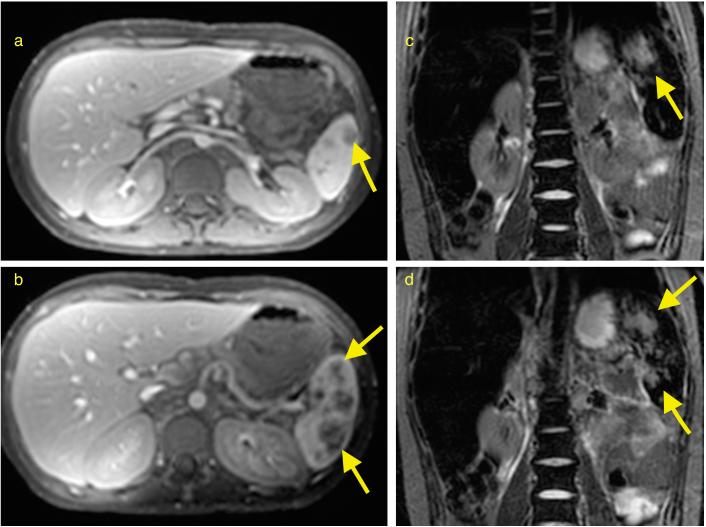

An example of the MR signal enhancement obtained in our patients is shown in figure 1. Ferumoxytol provided strong positive T1-enhancement and strong negative T2-effects due to iron uptake in macrophages on MR images. For 85 injections in 49 pediatric and 19 young adult patients, four mild adverse events were noted within one hour of injection: Two pediatric patients developed a transient hypotension, and one pediatric patient developed nausea, all of which resolved without intervention. One young adult patient developed warmness and erythema at the injection site. We stopped the infusion and the warmness and erythema were also self-resolving within 90 minutes.

Figure 1.

Ferumoxytol-enhanced magnetic resonance images of a 12-year old patient with lymphoma: (a, b) Axial T1-weighted FSPGR 15°/0.98ms/8.65ms (flip angle/TR/TE) images 48 h after injection of ferumoxytol at a dose of 5 mg Fe/kg shows marked increased signal (hyperintense) enhancement of abdominal vessels and visceral organs, delineating several lesions in the spleen (arrows). (c, d) Coronal STIR 5000ms/57.23ms/150ms (TR/TE/TI) images 48 h after ferumoxytol administration demonstrate decreased signal (hypointense) enhancement of the liver, spleen and bone marrow, outlining T2-hyperintense spleen lesions.

Vital signs

Both patients with transient hypotension were sedated for the MRI scan and ferumoxytol infusion. The first (Patient 1, Table 2) was a nine year old patient who showed fluctuation of blood pressure after injection with a maximal decrease in SBP of 12 mmHg (from 85 mmHg before injection to 73 mmHg at 60 minutes after injection) and a maximal decrease in DBP of 22 mmHg (from 56 mmHg before injection to 34 mmHg at 60 minutes after injection) while the HR remained within the normal range (60-83 bpm). The patient was monitored for another 30 minutes, and the blood pressure increased to 82/40 mmHg at 90 minutes post injection. The second (Patient 2, Table 2) was a seven year old patient who showed a gradual decline in blood pressure with a maximal decrease in SBP by 15 mmHg (from 91 mmHg before injection to 76 mmHg at 60 minutes after injection) and a maximal decrease in DBP of 17 mmHg (from 47 mmHg before injection to 30 mmHg at 60 minutes after injection) while the HR remained in the normal range (75-87 bpm). The blood pressure increased to 111/56 mmHg at 90 minutes after injection. Of note, most of the previously reported serious hypersensitivity reactions at other centers occurred during administration or within 30 minutes after administration (26).

Table 2.

Vital signs following ferumoxytol injection

| Pre | 15 min | 30 min | 45 min | 60 min | 90 min | p-value for time | p-value for sedation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg, Mean ± Standard Error) | ||||||||

| Pediatric | ||||||||

| Non-sedated | 110±2 | 109±2 | 111±2 | 109±3 | 110±2 | - | 0.26 | <0.0001 |

| Sedated | 80±4 | 83±4 | 81±4 | 86±4 | 87±4 | - | ||

| Patient 1 | 85 | 96 | 78 | 83 | 73 | 82 | ||

| Patient 2 | 91 | 85 | 79 | 76 | 76 | 111 | ||

| Young Adult | 112±3 | 112±3 | 112±3 | 118±4 | 116±4 | 0.27 | - | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg, Mean ± Standard Error) | ||||||||

| Pediatric | ||||||||

| Non-sedated | 63±2 | 63±2 | 64±2 | 63±2 | 63±2 | - | 0.50 | <0.001 |

| Sedated | 44±3 | 41±3 | 45±4 | 46±3 | 45±3 | - | ||

| Patient 1 | 56 | 47 | 58 | 50 | 34 | 40 | ||

| Patient 2 | 47 | 47 | 35 | 32 | 30 | 56 | ||

| Young Adult | 70±2 | 71±2 | 69±2 | 74±3 | 77±3 | 0.13 | - | |

| Heart rate (bpm, Mean ± Standard Error) | ||||||||

| Pediatric | ||||||||

| Non-sedated | 89±5 | 89±5 | 85±5 | 86±5 | 82±5 | - | 0.01 | 0.49 |

| Sedated | 82±3 | 81±3 | 83±3 | 82±3 | 81±3 | - | ||

| Patient 1 | 73 | 83 | 71 | 66 | 60 | 56 | ||

| Patient 2 | 75 | 83 | 85 | 88 | 87 | 79 | ||

| Young Adult | 85±4 | 84±4 | 85±4 | 83±4 | 88±4 | 0.47 | - | |

Model mean +/− standard error for vital signs following ferumoxytol injection (N=65 for pediatric patients, and N=20 for young adults).

Statistical analysis of our data revealed no significant changes over time in mean vital signs, including SBP and DBP, following ferumoxytol injection. There was a significant difference between sedated and non-sedated patients (Table 2; p<0.01), with higher blood pressure values in the latter. But both groups showed no significant change in either SBP or DBP over time (p=0.26 and 0.50, respectively). Similarly, no significant changes in HR (p=0.47), SBP (p=0.27) or DBP (p=0.13) were shown in young adults. One 16-year old patient presented with nausea within five minutes after a one-time only ferumoxytol injection. The nausea did not lead to vomiting and resolved within one hour after ferumoxytol administration without intervention. This symptom was likely related to the drug administration and not secondary to hypotension as the SBP of the patient remained stable above 90 mmHg.

The one case of warmness during injection with subsequent erythema of the skin at the injection site occurred in one of our young adult patients. We immediately stopped the infusion and monitored the patient. No further symptoms of an allergic reaction were observed or reported by the patient. The warmness and erythema were self-resolving within the extended monitoring period of 90 minutes.

We did not observe hypersensitivity reactions in our 49 pediatric and 19 young adult patients, including seven patients who received repetitive ferumoxytol administrations (a total of 24 injections). We observed the injection site for above mentioned local reactions and except for one patient did not see any other adverse reactions within the observation period of up to 60 minutes. None of our patients reported objective side effects at their clinical follow up visits, up to 35 days after ferumoxytol injection.

Hematology

Statistical analysis of CBCs following all 26 injections in 23 pediatric patients revealed no statistically or clinically significant changes in Hgb (p=0.74), Hct (p=0.57) and RBC counts (p=0.24) (Table 3). With 12 anemic and 11 non-anemic patients at the time of ferumoxytol injection, we investigated the effect of ferumoxytol in each population respectively. There was no significant increase in Hgb (p=0.37), Hct (p=0.32) or RBC (p=0.16) in anemic patients. Similarly no significant increase was seen in the non-anemic patients with Hgb (p=0.42), Hct (p=0.65) or RBC (p=0.97). Thus, the applied “diagnostic” ferumoxytol dose for MR imaging had no therapeutic effect.

Table 3.

Clinical laboratory values following ferumoxytol injection in pediatric patients

| Pre/Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | Day 28 | p-value for time effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) (N=26a) | 11.3±0.2 | 11.3±0.2 | 11.3±0.2 | 11.4±0.3 | 11.3±0.3 | 0.74 |

| Hematocrit (%) (N=26a) | 33.8±0.6 | 33.7±0.5 | 33.9±0.6 | 34.0±0.7 | 33.8±0.9 | 0.57 |

| Red Blood Cell counts (106 per μL) (N=26a) | 4.12±0.06 | 4.11±0.05 | 4.11±0.06 | 4.09±0.07 | 4.04±0.09 | 0.24 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) (N=34b) | 0.70±0.04 | 0.70±0.04 | 0.67±0.04 | 0.63±0.06 | 0.63±0.07 | 0.76 |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen (mg/dL) (N=19) | 15±1 | 15±1 | 13±1 | 12±1 | 13±1 | 0.52 |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/L) (N=27) | 31±5 | 29±4 | 27±3 | 25±4 | 23±4 | 0.15 |

| Alanine transaminase (U/L) (N=27) | 49±8 | 51±7 | 49±6 | 45±7 | 37±6 | 0.26 |

Model mean +/− standard error for clinical laboratory values following ferumoxytol injection.

26 injections in 23 pediatric patients

34 injections in 33 pediatric patients

Renal Parameters

Thirty-three pediatric patients received serial serum creatinine evaluations after ferumoxytol injection, including one patient who received multiple injections. There was no statistically significant change of serum creatinine (p=0.76) after ferumoxytol injection (Table 3). 46 pediatric patients had creatinine levels within normal range (<1.2 mg/dL) before and after ferumoxytol injection and three pediatric patients had high baseline creatinine levels (1.3, 1.6, 1.8 mg/dL, respectively) before injection. All three pediatric patients had a history of renal allograft transplantation with chronically elevated creatinine levels, and none showed a further increase in creatinine levels after ferumoxytol administration. A similar trend was observed for BUN levels in 19 pediatric patients (p=0.52) (Table 3). The findings are consistent with previous reports that ferumoxytol is phagocytosed by macrophages in the reticuloendothelial system, not eliminated through the kidneys and therefore well tolerated by patients with renal insufficiency (1, 15).

Liver Parameters

To assess potential liver toxicity of ferumoxytol we examined ALT and AST levels in 27 pediatric patients. The ALT levels showed minimal, statistically non-significant changes over time (p=0.26) (Table 3). In addition 19 out of 27 pediatric patients demonstrated no significant change in AST levels (p=0.15), suggesting no liver toxicity of ferumoxytol in these patients (Table 3). Eight pediatric patients showed AST levels above the normal range, which could be explained by concomitant chemotherapy or other chronic conditions. Two patients with 1.5 fold elevation of AST received chemotherapy at the time of ferumoxytol injection, including E. coli asparaginase and high dose methotrexate which are both known for their hepatotoxicity (27).

Discussion

Our data showed that ferumoxytol has an excellent safety profile as an “off-label” intravenous MR contrast agent and no statistically significant or clinically relevant abnormalities were noticed in the laboratory tests of 21 female and 28 male pediatric patients. To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective report on the safety profile of ferumoxytol in pediatric and young adult patients. In total, we observed 4 mild adverse events in 68 patients. We noted three mild adverse events in our pediatric patients who received a total of 65 ferumoxytol injections: Two cases of mild hypotension and one case of nausea. Furthermore, we noted one mild adverse event that was warmness and erythema at the injection site in one young adult patient.

There are potential safety concerns with regard to intravenous iron oxide administration for MR imaging. The most important safety concern for ferumoxytol is an anaphylactic reaction (19). Although all iron compounds carry a risk of hypersensitivity, the likelihood of death is rare (1 for every 5 million doses IV iron) (28). Ferumoxytol has a carboxymethyldextran coat to further decrease the hypersensitivity capability. We did not observe any hypersensitivity reaction in the 49 pediatric patients. This is in accordance with previous case reports, stating lack of allergic reactions in a study of six pediatric patients (20). Hypersensitivity reactions were reported in 0.2% of adult CKD patients who received ferumoxytol for anemia treatment (1). This frequency seems to be in a similar range compared to gadolinium-based MR contrast agents: Fakhran et al. reported that acute adverse events to gadobenate dimeglumine occurred at a frequency of 0.18% in more than 130,000 administrations, including 5% serious adverse events (29). On the contrary, Murphy et al. reported severe hypersensitivity reactions in 0.001% of 687,255 gadobenate dimeglumine injections (30). One study reported hypersensitivity-like reaction rate of 0.07% in 65,009 adult patients and only 0.04% in 13,344 pediatric patients younger than 19 years over various gadolinium based contrast agents. This might indicate, that pediatric patients are less prone to hypersensitivity-like reactions compared to adult patients (31). Indeed, we did not observe any hypersensitive reactions in our 49 pediatric patients but one case of erythema at the local injection site in one of the 19 young adult patients. Yet comparing percentages over different studies is difficult due to the low incidence of these events and differences in study design and assessment of adverse events.

A second important safety concern of ferumoxytol is hypotension. Safety reports from several Phase III randomized controlled trials described hypotension in 1.9% or less of adult patients with CKDs (1, 15-17). Two of the pediatric patients also exhibited a transient hypotension, although they had simultaneous sedation, which could be the cause for the transient hypotension as the statistical significant difference between the unsedated and sedated patients show. Serious hypotension was reported in other studies to be accompanied by dizziness, blurred vision, nausea, clammy skin, tachycardia and syncope (32). None of these signs or symptoms were observed in unsedated pediatric or young adult patients in our study. Hypotension might be explained by the free-iron-like reaction and not necessarily anaphylaxis (33). The free iron is released from the iron-compound during intravenous application when the transferrin binding capacity for iron is exceeded. Iron in a free state might be leading to anaphylactic-like symptoms or might be the reason for the skin erythema in one of the patients (34). However, a recently published study shows that if applied according to recommendations, only a minimum of free iron emerges from ferumoxytol during intravenous injection (35) and that this amount of free iron should not have any clinical relevance (36). A previous study showed that high-rate, high-volume administration of iron-carbohydrate compounds can lead to hypotension, nausea, back and chest pain through complement activation by labile iron (37). The frequency of hypotensive reactions may be decreased by slow infusion and dilution of the iron compound. This is the rationale for the FDA recommendation to administer diluted ferumoxytol slowly under continuous blood pressure monitoring and consistent with recommended administration modes for other iron oxide products. These methods have been used for clinical MR imaging in Europe for many years (26). Assuming the free-iron-like complement-activation nature of the hypotensive reaction, treatment with antihistamines may not be helpful, and may even escalate initial minor symptoms into hemodynamically significant serious events. Importantly, the recent boxed warning for ferumoxytol by the FDA states that “of the 79 cases with serious adverse events, 18 were fatal, despite immediate medical intervention”. Details of these cases are urgently needed to generate improved rescue protocols. It is possible that the presumed anaphylactic reactions were in fact hypotensive reactions, and would have benefitted from treatment with volume administration instead of anaphylactic reaction treatment with vasopressor infusion (38). Guidelines for the treatment of iron infusion related reactions specifically recommend fluids ahead of anaphylaxis therapy (34).

Other reported adverse events related to the administration of iron oxide nanoparticles include nausea, dizziness and back pain (1). Nausea occurred in one of the patients in our study. It was a relatively common adverse event in other trials, occurring at a frequency of 0.4% in a single dose trial and 3.1% in a two-dose trial (1, 17). Furthermore, it is a well described side effect in children after injection of especially high-osmolality iodinated contrast agents, although ferumoxytol has different physical properties (39). The osmolality of ferumoxytol is 270-330 mOsmol/kg, whereas gadolinium-based contrast agents have an osmolality ranging between 630 mOsmol/kg for gadoteriol up to 1960 mOsmol/kg for gadopentetate dimeglumine (40, 41). Comparing 680 patients receiving ferumoxytol intravenous to 280 patients treated with oral iron supplements, nausea is far less frequent in the ferumoxytol treated (40).

An advantage of ferumoxytol compared to gadolinium-chelates is its absence of renal elimination and safety in patients with impaired renal function (42). Our patients showed minimal changes in laboratory values related to renal function, including creatinine and BUN. Ferumoxytol is an FDA-approved drug for intravenous treatment of anemia; with a therapeutic dose of two 510 mg injections within 3-8 days apart and resulting in an average increase of 1.0 g/dl in Hgb (1, 40). Landry et al. showed that single ferumoxytol doses up to 420 mg had no effect on the baseline Hgb or Hct levels in healthy adults as well as CKD patients (13). The doses we injected for MR imaging in pediatrics and young adults were approximately less than 1/3 of the therapeutic dose. Accordingly, we did not observe a significant increase in Hgb. Ferumoxytol is phagocytosed and slowly metabolized by the reticuloendothelial system. With the exception of iron related parameters, other investigators confirmed in adult patients that laboratory values related to liver function such as AST and ALT were not altered either (15, 17). Nevertheless, there are no long-term studies available on the metabolism of ferumoxytol, therefore deleterious side effects cannot be ruled out completely.

We acknowledge several limitations to our study. Severe adverse events are rare, and require a large sample size to determine their frequency. Demonstrating that the mean remains within the normal range neither demonstrates that all of the individual values will do so nor that ferumoxytol could not be associated with an extreme but rare value. Also, we only monitored the vital signs for up to one hour after ferumoxytol injection. Despite the fact that allergic reactions typically occur within the first few minutes after administration, the FDA recommends monitoring for at least 30 minutes. We monitored the patients for one hour, twice the recommended time. Furthermore, most patient's vital signs were obtained once a week after the injection at their clinical routine follow-up appointments. Since we only evaluated laboratory values of children who underwent a blood draw as part of their clinical routine, laboratory data were only available for 50% of our pediatric patients. The majority of the young adult patients were kidney transplant patients who did not receive routine laboratory blood draws. This further reduced our sample size and ultimately the power of our study. Nevertheless, we acquired safety data in a cohort equivalent in population to typical phase II studies. Our study design limited our ability to directly compare ferumoxytol with conventional gadolinium-based contrast agents. Our study was also complicated by concomitant chemotherapy and other medications. However, this represents the typical clinical scenario.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that ferumoxytol doses of up to 5 mg Fe/kg administered “off-label” for MR imaging were well tolerated among 49 pediatric and 19 young adult patients suffering from various tumors or kidney transplants without major adverse events, or signs of hematologic and kidney impairment or liver toxicity. These results may encourage further investigations in larger prospective studies.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by R01 HD081123-01A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a grant from the Translational Research and Applied Medicine (TRAM) Program at Stanford University, by National Institute of Health grant CA137488 and by the Walter S. and Lucienne Driskill Foundation to Oregon Health & Science University and Edward A. Neuwelt, MD.

References

- 1.Lu M, Cohen MH, Rieves D, Pazdur R. FDA report: Ferumoxytol for intravenous iron therapy in adult patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(5):315–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [9/3/2015];European Medicines Agency. Accessed at http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/medicines/002215/human_med_001569.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124.

- 3.Klenk C, Gawande R, Uslu L, et al. Ionising radiation-free whole-body MRI versus (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scans for children and young adults with cancer: a prospective, nonrandomised, single-centre study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):275–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70021-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson EM, Guillaume DJ, Dosa E, et al. Dual contrast perfusion MRI in a single imaging session for assessment of pediatric brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 2012;109(1):105–14. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0872-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrell BT, Hamilton BE, Dosa E, et al. Using iron oxide nanoparticles to diagnose CNS inflammatory diseases and PCNSL. Neurology. 2013;81(3):256–63. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfd8f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daldrup-Link HE, Golovko D, Ruffell B, et al. MRI of tumor-associated macrophages with clinically applicable iron oxide nanoparticles. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(17):5695–704. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon GH, von Vopelius-Feldt J, Fu Y, et al. Ultrasmall supraparamagnetic iron oxide-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of antigen-induced arthritis: a comparative study between SHU 555 C, ferumoxtran-10, and ferumoxytol. Invest Radiol. 2006;41(1):45–51. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000191367.61306.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Intracranial Gadolinium Deposition after Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging. Radiology. 2015:150025. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15150025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perazella MA. Current status of gadolinium toxicity in patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):461–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06011108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W, Tutton S, Vu AT, et al. First-pass contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography in humans using ferumoxytol, a novel ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO)-based blood pool agent. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21(1):46–52. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prince MR, Zhang HL, Chabra SG, et al. A pilot investigation of new superparamagnetic iron oxide (ferumoxytol) as a contrast agent for cardiovascular MRI. J Xray Sci Technol. 2003;11(4):231–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varallyay CG, Nesbit E, Fu R, et al. High-resolution steady-state cerebral blood volume maps in patients with central nervous system neoplasms using ferumoxytol, a superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33(5):780–6. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landry R, Jacobs PM, Davis R, et al. Pharmacokinetic study of ferumoxytol: a new iron replacement therapy in normal subjects and hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25(4):400–10. doi: 10.1159/000087212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storey P, Lim RP, Chandarana H, et al. MRI assessment of hepatic iron clearance rates after USPIO administration in healthy adults. Invest Radiol. 2012;47(12):717–24. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31826dc151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spinowitz BS, Kausz AT, Baptista J, et al. Ferumoxytol for treating iron deficiency anemia in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(8):1599–605. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Provenzano R, Schiller B, Rao M, et al. Ferumoxytol as an intravenous iron replacement therapy in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):386–93. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02840608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh A, Patel T, Hertel J, et al. Safety of ferumoxytol in patients with anemia and CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(5):907–15. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hetzel D, Strauss W, Bernard K, et al. A Phase III, randomized, open-label trial of ferumoxytol compared with iron sucrose for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with a history of unsatisfactory oral iron therapy. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(6):646–50. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [9/3/2015];Communication FDS. Accessed at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm440138.htm.

- 20.Hassan N, Cahill J, Rajasekaran S, Kovey K. Ferumoxytol infusion in pediatric patients with gastrointestinal disorders: first case series. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(12):e63. doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Department of Health and Human Services [09/20/2015];2014 doi: 10.3109/15360288.2015.1037530. Accessed at http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.National Cancer Institue [9/3/2015];2015 Accessed at http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm.

- 23.Kleinman ME, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, et al. Part 14: pediatric advanced life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(18 Suppl 3):S876–908. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pediatric Advanced Life Support: Provider Manual. American Heart Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janus J, Moerschel SK. Evaluation of anemia in children. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(12):1462–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernd H, De Kerviler E, Gaillard S, Bonnemain B. Safety and tolerability of ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide contrast agent: comprehensive analysis of a clinical development program. Invest Radiol. 2009;44(6):336–42. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181a0068b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King PD, Perry MC. Hepatotoxicity of chemotherapy. Oncologist. 2001;6(2):162–76. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-2-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wysowski DK, Swartz L, Borders-Hemphill BV, et al. Use of parenteral iron products and serious anaphylactic-type reactions. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(9):650–4. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fakhran S, Alhilali L, Kale H, Kanal E. Assessment of rates of acute adverse reactions to gadobenate dimeglumine: review of more than 130,000 administrations in 7.5 years. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204(4):703–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy KP, Szopinski KT, Cohan RH, et al. Occurrence of adverse reactions to gadolinium-based contrast material and management of patients at increased risk: a survey of the American Society of Neuroradiology Fellowship Directors. Acad Radiol. 1999;6(11):656–64. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(99)80114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dillman JR, Ellis JH, Cohan RH, et al. Frequency and severity of acute allergic-like reactions to gadolinium-containing i.v. contrast media in children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(6):1533–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Heart Association 2014 Accessed at http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HighBloodPressure/AboutHighBloodPressure/Low-Blood-Pressure_UCM_301785_Article.jsp.

- 33.Zanen AL, Adriaansen HJ, van Bommel EF, et al. ‘Oversaturation’ of transferrin after intravenous ferric gluconate (Ferrlecit(R)) in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11(5):820–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rampton D, Folkersen J, Fishbane S, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to intravenous iron: guidance for risk minimization and management. Haematologica. 2014;99(11):1671–6. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.111492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koskenkorva-Frank TS, Weiss G, Koppenol WH, Burckhardt S. The complex interplay of iron metabolism, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species: insights into the potential of various iron therapies to induce oxidative and nitrosative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:1174–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neiser S, Rentsch D, Dippon U, et al. Physico-chemical properties of the new generation IV iron preparations ferumoxytol, iron isomaltoside 1000 and ferric carboxymaltose. Biometals. 2015;28(4):615–35. doi: 10.1007/s10534-015-9845-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Wyck DB. Labile iron: manifestations and clinical implications. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(Suppl 2):S107–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000143816.04446.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dager WE, Sanoski CA, Wiggins BS, Tisdale JE. Pharmacotherapy considerations in advanced cardiac life support. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(12):1703–29. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.12.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen MD, Herman E, Herron D, et al. Comparison of intravenous contrast agents for CT studies in children. Acta Radiol. 1992;33(6):592–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Food and Drug Administration. Pages. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022180lbl.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2015.

- 41.Runge VM. Safety of approved MR contrast media for intravenous injection. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12(2):205–13. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200008)12:2<205::aid-jmri1>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlaudecker JD, Bernheisel CR. Gadolinium-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(7):711–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]