Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine the feasibility of using quantitative changes in vaginal permeability to small molecules as a measure of candidate microbicide toxicity.

STUDY DESIGN

Controlled, open-labeled, prospective study. Seven healthy women received a single vaginal dose of hydroxyethylcellulose gel (HEC), nonoxynol-9 (N-9), or K-Y Jelly. Each gel was radiolabeled with a small molecule (99mTc-DTPA) followed by 12-hour blood and urine collection. Pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters of 99mTc -DTPA were calculated to compare the impact of each gel on vaginal permeability. Each woman served as her own control. The Friedman test with post hoc Wilcoxon test was used to detect differences amongst the gels.

RESULTS

Vaginal permeability of 99mTc-DTPA was highest for the N-9 radiolabel. N-9 plasma area under the concentration curve was 2.7-fold higher (P=0.04) and peak concentration was 3-fold higher (P=0.04) compared to HEC. There were no significant PK parameter differences between HEC and K-Y Jelly or between N-9 and K-Y Jelly. Cumulative dose-adjusted median (interquartile range) 12-hour timed urine gamma activity was 66.70 x10−4 μCi (27.90 – 152.00) following HEC dosing, 103.00 x10−4 μCi (98.20 – 684.00) following N-9 gel dosing, and 20.30 x10−4 μCi (11.10–55.90) following K-Y gel dosing. The differences between urine HEC and K-Y Jelly (P=0.047) and between N-9 and K-Y Jelly (P=0.016) were statistically significant.

CONCLUSIONS

It is feasible to measure differences in vaginal permeability among vaginal gels using a radiolabeled small molecule, though there are permeability differences that require a nuanced understanding of gel composition to interpret the results.

Keywords: HIV, N-9, permeability, HIV, microbicide, spermicide

INTRODUCTION

Microbicides are topically-applied drugs that prevent HIV sexual transmission through inhibition of HIV penetration into or replication within target cells and tissues. CAPRISA 004, a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical study of vaginal 1% tenofovir gel dosed vaginally both before and after sex, demonstrated a 39% reduction in HIV transmission in heterosexual women, which provided clinical proof-of-concept for topical microbicides in the prevention of HIV infection.[1] In two other randomized controlled trials, vaginal 1% tenofovir gel did not protect women in modified intent to treat analyses, but reduction in HIV risk was demonstrated in post hoc analyses among women who had detectable drug levels indicative of higher levels of adherence.[2, 3]

Microbicide development requires early identification of gel vehicles or active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) that might be toxic to the epithelium. Similarly, interpretation of microbicide trial results requires considering confounding sources of toxicity, including the gel vehicle and para-sexual activities (i.e. sexual lubricants, douching) to avoid incorrect attribution of toxicity to the microbicide’s API. An example is nonoxynol-9 (N-9), which was used for decades as an over-the-counter spermicidal agent. In a study among commercial sex workers, there was a 50% increased risk of HIV acquisition among N-9 recipients.[4]

In vitro experiments suggest that for some molecules, the vaginal mucosa is more permeable than colonic or intestinal tissue,[5] and is relatively comparable to the buccal mucosa.[6] These colon versus vaginal relationships are drug and vehicle specific. Our group has used permeability as a metric to compare changes in colonic mucosal integrity after dosing rectal microbicide candidates.[7] The purpose of this study was to compare vaginal permeability of a radiolabeled small molecule added to three gels–hydroxyethylcellulose (HEC), N-9, and K-Y JellyTM – as a simple, non-invasive assessment of the potential impact of each gel on cervicovaginal permeability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a comparative, open-label prospective study comparing vaginal permeability among three radiolabeled gels. Healthy women age 18 to 45 years with regular menstrual cycles were invited to participate. Women agreed to use effective contraception and abstain from vaginal intercourse, vaginal products, or vaginal sex toy insertion for seven days prior to and following dosing visits. Women with a sexually transmitted infection (STI), vaginal candidiasis, or bacterial vaginosis within eight weeks of enrollment were excluded. Known history of genital herpes, current urinary tract infection, cervicovaginal procedure within 3 months, hysterectomy, pregnancy, breastfeeding, undiagnosed irregular menses, urogenital malformations and allergy to gel components, were additional exclusion criteria. Written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Study gels

The three vaginal gels were HEC, N-9 (Gynol II Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Titusville, NJ, USA), and K-Y JellyTM. HEC gel, which is an iso-osmolar (290–300 mOsm/kg) non-detergent gel similar to universal placebo, was selected as the negative control. Because HEC is iso-osmolar and does not contain any ingredients at concentrations that are expected to have possible effects on the mucosa, we did not expect that HEC would be associated with any permeability changes. Two percent N-9, which is a hyper-osmolar (1200 mOsm/kg) detergent gel, was selected as the positive control because it demonstrated detectable permeability changes in our prior rectal permeability study.[7] K-Y Jelly, which is a hyper-osmolar (2007 mOsm/kg) gel, was selected for comparison with the positive and negative controls to understand if the hyperosmolar character of K-Y Jelly by itself, but without the detergent properties of N-9, would result in permeability changes.[8] 3.5 mL of each gel was radiolabeled with technetium-99m diethylene triamine pentaacetic acid (99mTc-DTPA) that has a molecular weight of 487.31 and was supplied by a commercial radiopharmacy (Cardinal Health, Beltsville, MD).[9] DTPA is highly water soluble and is cleared 100% by glomerular filtration.[10, 11] The dose planned for delivery to the research participant was 500 μCi 99mTc. The actual dose delivered and retained is described below.

Procedures

A single 3.5mL dose of a gel was administered at separate visits and administered in the same sequence – HEC gel, N-9, and K-Y Jelly. Dosing visits were scheduled at the same time in each participant’s menstrual cycle to avoid any potential impact of hormonal variation on vaginal permeability. The menstrual phase was not standardized for the entire sample as some participants underwent procedures only in the follicular phase while others underwent procedures only in the luteal phase. At least a 3 week washout period was scheduled between doses, which was more than sufficient for complete clearance of all product from the prior visit, complete radioactive decay of the administered isotope, and complete healing of vaginal mucosa. A negative serum pregnancy test was required before gel application and a Foley catheter was inserted to obtain an accurate measurement of urine 99mTc, while avoiding urine contamination by vaginal gel leakage. Radiolabeled gel was injected into the posterior vaginal fornix using a luer-lock applicator (product 35–1107; Professional Compounding Centers of America, Houston, TX) attached to the dosing syringe. The residual radioactivity in each syringe was measured using a dose calibrator (CRC 15-W; Capintec, Ramsey, NJ) and the time of measurement recorded. The retained dose was calculated from the dose administered minus the residual radioactivity in the syringe after dosing.

Participants remained supine for the first hour after dosing to facilitate specimen collection and allowed to ambulate ad lib afterwards. Sanitary napkins were used by all participants and were collected and measured for radioactivity to account for leakage of the isotope labeled gel from the vagina. Whole venous blood was collected pre-dose and at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours after gel insertion; plasma was separated for measurement of gamma activity. Urine was collected pre-dose and 2, 4, 8, and 12 hours after gel insertion. After 12 hours, residual gel was rinsed from the vagina using 10 mLs of an isotonic salt balanced solution (Normosol-RTM, Hospira, Inc.).

Gamma counting

Gamma emissions in plasma and urine specimens were measured on a gamma counter (Wizard2 automatic gamma counter model 2480, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) within a 110–150-keV energy window. Samples were corrected for background activity and instrument detector efficiency. Gamma emission limit of quantitation was defined as background + (3 x square root of background). Any gamma counts below this value (approximately 22 counts per minute [cpm]), were imputed with a value of “0” for data analysis purposes and considered not distinguishable from naturally-occurring background radiation. To determine the cumulative urine gamma activity for a specified interval, gamma counts for urine aliquots were corrected for urine volume collected in the interval and sampling interval duration. Sanitary pads and paper tissues were measured in the dose calibrator. All gamma count results were converted to microcuries (μCi) and decay corrected to the time of dosing.

Data analysis

Permeability was quantitatively assessed by measuring the amount of plasma and urine 99mTc-DTPA over a 12 hour period of observation. Plasma and urine results were also dose-adjusted by dividing the radioactivity (in a plasma sample or urine interval) by the total amount of radioactivity retained by each subject. Plasma permeability was quantitatively described using traditional pharmacokinetic (PK) parameter estimation, including peak concentration (Cmax), time to maximum concentration (Tmax), and area under the concentration curve from 0–12 hours (AUC0–12) using the linear trapezoidal method. PK parameters were calculated using Microsoft Excel.

Permeability measures in blood and urine were summarized using descriptive statistics. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated, unless otherwise stated. Urine isotope measurement was expressed as cumulative amount of isotope collected in the urine, expressed as a fraction of the dose retained. Each woman served as her own control whereby permeability of each study gel was compared to the other gels. Given the small sample sizes and the inability to conclusively evaluate data distribution assumptions, the non-parametric Friedman test was used to detect differences among the three conditions. If the Friedman test was statistically significant with a 2-sided p-value of 5%, then a Wilcoxon sign rank test was performed to test for differences between study gels in a paired fashion; p-values listed are for the Wilcoxon test. GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA) was used to perform the analyses.

RESULTS

Eighteen women were screened and 8 women were enrolled. Screen failures were due to a new STI (70%), greater than 2 sexual partners in the past year (10%), and schedule conflicts (20%). One enrolled participant dropped out after an STI diagnosis, leaving 7 evaluable participants. Median (IQR) age was 30 years (26.5 – 33). Fifty-seven percent of participants were black, 14% were white, and 29% were mixed race.

Plasma

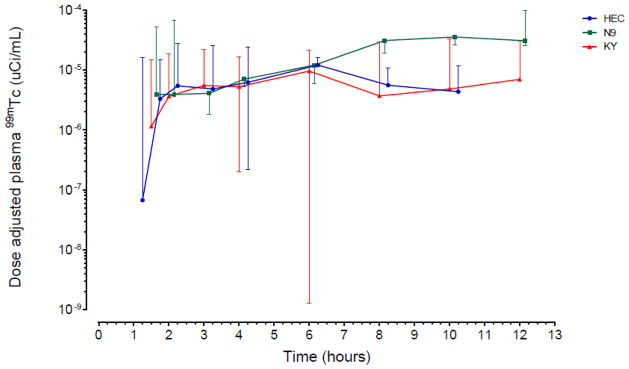

Vaginal permeability of 99mTc-DTPA was highest following the N-9 study gel. N-9 dose adjusted AUC0–12 was 1.90 (1.59 – 9.88) μCi-hrs/mL and dose adjusted Cmax 0.36 (0.29 – 1.19) μCi/mL (Table 1). N-9 AUC0–12 was 2.7-fold higher (P=0.04) and Cmax was 3-fold higher (P=0.04) than HEC. K-Y Jelly AUC0–12 was 0.83-fold lower and Cmax was 0.79-fold lower than HEC, however, these results were not statistically significant. Peak concentration occurred after 3 to 4 hours with HEC and K-Y Jelly, whereas peak concentrations occurred after nearly 10 hours with N-9 (not statistically significant, P=0.40). There was a similar concentration over time pattern noted with all three vehicles during the first 6 hours, after which N-9 permeability continued to increase while HEC and K-Y Jelly permeability decreased (Figure 1). There were no statistically significant plasma PK parameter differences between HEC and K-Y Jelly or between N-9 and K-Y Jelly (all P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Plasma and urine mucosal permeability

| PK Parameter | HEC | N-9 | KY Jelly |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC0–12, μCi-hrs/mL x 10−6, dose-adjusted | 0.70 (0.30 – 1.30) § | 1.9 (1.59 –9.88) § | 0.58 (0.08 – 2.02) |

| Cmax, μCi/mL x 10−6, dose-adjusted | 0.12 (0.06 – 0.21) § | 0.36 (0.29 – 1.19) § | 0.10 (0.03 – 0.28) |

| Tmax, hours after dosing | 4.00 (3.00 – 8.03) | 9.98 (4.09 – 11.01 ) | 3.00 (2.97 – 8.00) |

| Cumulative urine 99mTc (μCi) as fraction of retained dose x 10−4 (collection interval in hours after dosing) | |||

| 0–2 | 1.97 (0.42 –5.13) | 2.04 (0 –33.30) | 0.46 (0.20 –4.31) |

| 0–4 | 14.30# (3.82 –61.70) | 12.70 (6.28– 134.00) | 2.53# (1.52 –22.50) |

| 0–8 | 32.70# (15.20 –122.00) | 48.90* (30.90 –461.00) | 14.00#* (6.70 –46.80) |

| 0–12 | 66.70# (27.90 –152.00) | 103.00* (98.20 –684.00) | 20.30#* (11.10– 55.90) |

| Residual CVL (fraction of retained dose) | 0.06 (0.02– 0.12) | 0.09 (0.03– 0.19)* | 0.03 (0.01– 0.11)* |

μ Ci: microcurie

AUC, Cmax, and urine are divided by retained dose (μCi), and expressed as a fraction

Data are median (IQR)

Wilcoxon signed-rank tests: P<0.05 for comparisons between

HEC and N9;

HEC and KY Jelly;

N-9 and KY Jelly.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Plasma 99mTc isotope administered versus time, dose-adjusted (B) Urine cumulative 99mTc isotope, dose-adjusted

Urine

After 2 hours, there was significantly less cumulative gamma activity in urine following K-Y Jelly dosing than compared to the other gel dosing conditions (Table 1). The cumulative difference between HEC and K-Y Jelly was statistically significant beginning at 4 hours and throughout the 12 hours following dosing (all P<0.05), while the difference between N9 and K-Y Jelly was statistically significant after 8 hours and 12 hours following dosing (P=0.03 and P=0.016, respectively). There were no differences between N-9 and HEC. The 12 hour cumulative urine activity over time pattern was similarly shaped for all vehicles, however K-Y Jelly demonstrated the lowest concentration of 99mTc (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that it is feasible to measure quantitative changes in systemic penetration (plasma and urine) of a small molecules (DTPA) as one means of assessing differences in the effects of vaginal gels on cervicovaginal mucosal permeability. However, interpretation of this quantitative permeability is complex and not necessarily indicative of toxicity as described below.

Vaginal permeability of small molecules has been previously shown. Pommerenke vaginally administered a radiolabeled saline solution to women who were postpartum, had a recent hysterectomy, or normal controls.[12] Plasma radiosignal was detected within thirty minutes following dosing. Over 24 hours, the radiolabel fraction absorbed ranged from 0.11% in normal controls to 30% in post-partum women.[12] John, et al., vaginally administered 14C-flutrimazole to healthy post-menopausal volunteers and tracked plasma radioactivity concentration over 72 hours finding the mean Tmax 28 hours following dosing and 8% of the radiolabeled drug absorbed. [13]

In our study, cervicovaginal permeability for DTPA into plasma was greater following N-9 dosing compared to HEC. The time course of N-9 related permeability changes also persisted far longer (at least in some individuals) compared to the HEC gel suggesting an ongoing alteration of the mucosal integrity with N-9. These N-9 findings are consistent in direction with prior clinical studies which found that N-9 increased risk of HIV infection compared to a HEC placebo, though we provide no direct evidence for relatedness.[4] In vitro studies provide evidence that N-9 disrupts epithelial tight junctions, down-regulates junctional proteins, enhances movement of HIV across mucosal barriers,[14] and destroys columnar epithelium within minutes,[15] providing mechanistic explanations for increased HIV transmission after N-9 exposure.[7, 16]

The K-Y Jelly results indicate the complexity of using permeability as a measure of toxicity. K-Y Jelly permeability was quantitatively lower than either HEC or N-9, although these differences were statistically significant only in the case of urine. Variability in K-Y Jelly permeability was also greater than for the other study gels, which likely contributed to K-Y Jelly permeability not being statistically significantly lower than N-9 in plasma despite several fold differences in all PK parameter medians. Additionally, there are reports of similarly hyperosmolar gels without N-9 causing colonic mucosal damage.[8] In these studies, hyperosmolar products demonstrate lower colonic permeability than shown for near iso-osmolar controls. A hyperosmolar gel or fluid, in the absence of an established mucosal toxin like N-9, could result in either one or both scenarios: (1) decreased permeability, due to fluid shifts into the vaginal lumen, driven entirely by osmolality itself, and/or (2) increased permeability, if high osmolality is associated with mucosal tissue damage.

Absent a much lower permeability of K-Y Jelly compared to HEC (expected based on osmolality differences), the K-Y Jelly findings in our study may reflect a balance of both hyperosmolar fluid shifts into the vaginal space as well as hyperosmolar damage to cervicovaginal epithelium, which we did not attempt to measure directly. Because of the great variability of the K-Y Jelly PK results, however, this has to remain a speculative explanation, though the findings are consistent with rectal dosing. Even so, this points out the complexity of separating mucosal damage from simple fluid shifts, measured as small molecule permeability as employed here.

Compared to prior N-9 studies of 99mTc-DTPA permeability in the colon, these vaginal permeability results showed a smaller magnitude and later peak effect.[17] Variability is also greater in these vaginal results compared to prior colon permeability results. These findings are consistent with the very different histology of colon versus cervicovaginal mucosa.

We measured urine in addition to plasma 99mTc-DTPA radioactivity because DTPA is rapidly filtered by the renal system and urine may be simpler to collect than blood. Further, urine samples contain larger amounts of radioactivity per sample, thus, increasing sensitivity. Plasma and urine provided consistent results with regard to the relative DTPA concentration time course for the gels, though not statistically significant. Though intended to reduce confounding vaginal radioactivity in urine, our use of a urinary catheter resulted in increased complexity compared to plasma sampling. In a separate study of cervicovaginal permeability, we did not use urinary catheters and we still detected a similar magnitude of alteration in mucosal permeability with 4% N-9 which was statistically different from a placebo gel.[18] Therefore, use of the Foley catheter does not appear to be necessary to detect large magnitude changes.

Our study has several limitations. The small sample size diminished our ability to detect any, but large, differences between the study gels which was worsened by larger than expected variability. Also, to avoid the confounding impact of biopsy on permeability, we did not include histologic assessment which might have helped differentiate the impact of direct mucosal toxicity from fluid flux. It would also be useful to compare the findings of other non-invasive tissue structure informative methods like optical coherence tomography useful in several non-human species.[19–21] We didn’t assess permeability effects of sex or seminal fluid, though we demonstrated no increased permeability related to anal intercourse with semen deposition in prior clinical studies of rectal gels.[22] Though all of the gels in this study have some degree of mucoadhesive properties and mucoadhesion may influence rate of drug release, we did not assess these properties.[23] Most importantly for vaginal microbicide development, we don’t know the clinical significance of these mucosal permeability changes for HIV acquisition risk, other than the risk associated with repeated use of N-9.[4]

Although measuring altered permeability of small molecules across the cervicovaginal epithelium is feasible, interpretation of the results is not straightforward, especially given multiple physicochemical differences between compared products. A combination of complementary toxicity assessments need to be employed simultaneously. Better non-invasive methods to evaluate the mucosal toxicity of vaginal microbicide candidates are needed.

IMPLICATIONS.

Establishing the safety of both vehicle and active pharmaceutical ingredient is an essential task in microbicide development, to be determined as soon as possible. This study suggests that a combination of microbicide toxicity assessments, i.e. cervicovaginal permeability, inspection, and histopathology, may need to be studied simultaneously.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants who volunteered for this study and the staff of the Johns Hopkins University Drug Development Unit and Clinical Pharmacology Analytical Laboratory.

FUNDING

This study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, Division of AIDS, Integrated Pre-Clinical/Clinical Program for HIV Topical Microbicides (U19 AI0882639). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIAID. This project has also been funded in part with federal funds from the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract No. HHSN272200800014C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010;329:1168–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:509–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rees H, Delany-Moretlwe S, Baron D, et al. FACTS 001 Phase III Trial of Pricoital Tenofovir 1% Gel for HIV Prevention in Women. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle, Washington. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Damme L, Ramjee G, Alary M, et al. Effectiveness of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on HIV-1 transmission in female sex workers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:971–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Bijl P, van Eyk AD. Comparative in vitro permeability of human vaginal, small intestinal and colonic mucosa. Int J Pharm. 2003;261:147–52. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Eyk AD, van der Bijl P. Comparative permeability of various chemical markers through human vaginal and buccal mucosa as well as porcine buccal and mouth floor mucosa. Arch Oral Biol. 2004;49:387–92. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs EJ, Lee LA, Torbenson MS, et al. Hyperosmolar sexual lubricant causes epithelial damage in the distal colon: potential implication for HIV transmission. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:703–10. doi: 10.1086/511279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Begay O, Jean-Pierre N, Abraham CJ, et al. Identification of personal lubricants that can cause rectal epithelial cell damage and enhance HIV type 1 replication in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2011;27:1019–24. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United States National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health. Toxnet Toxicology Data Network.

- 10.Klopper JF, Hauser W, Atkins HL, Eckelman WC, Richards P. Evaluation of 99m Tc-DTPA for the measurement of glomerular filtration rate. J Nucl Med. 1972;13:107–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Webb S. The Physicis of Radioisotope Imaging. In: Flower MA, editor. Webb's Physics of Medical Imaging. 2. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2012. p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pommerenke WT, Hahn PF. Absorption of Radioactive Sodium Instilled into the Vagina. Am J Obstet & Gynecol. 1943;46:853–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.John B, Wood SG, Ramis J, Izquierdo I, Forn J. Absorption and excretion of radioactivity after intravaginal administration of an advanced delivery system of 14C-flutrimazole vaginal cream to postmenopausal women. Arzneimittelforschung. 1998;48:512–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haase AT. Perils at mucosal front lines for HIV and SIV and their hosts. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:783–92. doi: 10.1038/nri1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catalone BJ, Kish-Catalone TM, Budgeon LR, et al. Mouse model of cervicovaginal toxicity and inflammation for preclinical evaluation of topical vaginal microbicides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1837–47. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1837-1847.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips DM, Sudol KM, Taylor CL, Guichard L, Elsen R, Maguire RA. Lubricants containing N-9 may enhance rectal transmission of HIV and other STIs. Contraception. 2004;70:107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leyva FJ, Bakshi RP, Fuchs EJ, et al. Isoosmolar enemas demonstrate preferential gastrointestinal distribution, safety, and acceptability compared with hyperosmolar and hypoosmolar enemas as a potential delivery vehicle for rectal microbicides. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29:1487–95. doi: 10.1089/aid.2013.0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuchs EJ, Schwartz JL, Friend DR, Coleman JS, Hendrix CW. A Pilot Study Measuring the Distribution and Permeability of a Vaginal HIV Microbicide Gel Vehicle using MRI, SPECT/CT, and a Radiolabeled Small Molecule. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2015 doi: 10.1089/aid.2015.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell BA, Vincent KL, Bourne N, Vargas G, Motamedi M. Optical coherence tomography for assessment of microbicide safety in a small animal model. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:046010. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.4.046010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent KL, Bell BA, Rosenthal SL, et al. Application of optical coherence tomography for monitoring changes in cervicovaginal epithelial morphology in macaques: potential for assessment of microbicide safety. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:269–75. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815abad8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent KL, Vargas G, Bourne N, et al. Image-based noninvasive evaluation of colorectal mucosal injury in sheep after topical application of microbicides. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:854–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leyva F, Fuchs EJ, Bakshi R, et al. Simultaneous Evaluation of Safety, Acceptability, Pericoital Kinetics, and Ex Vivo Pharmacodynamics Comparing Four Rectal Microbicide Vehicle Candidates. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2015 doi: 10.1089/aid.2015.0086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burruano BT, Schnaare RL, Malamud D. In vitro test to evaluate the interaction between synthetic cervical mucus and vaginal formulations. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2004;5:E17. doi: 10.1208/pt050117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]