Abstract

People with mental illness die decades earlier in our country when compared to the general public Most of this disparity is related to preventable and treatable chronic conditions, with many studies finding cancer as the second leading cause of death. Individual lifestyle factors, such as smoking or limited adherence to treatment, are often cited as highly significant issues in shaping risk among persons with mental illness. However, many contextual or systems-level factors exacerbate these individual factors and may fundamentally drive health disparities among people with mental illness. We conducted an integrative review in order to summarize the empirical literature on cancer prevention, screening, and treatment for people with mental illness. While multiple interventions are being developed and tested to address tobacco dependence and obesity in these populations, the evidence for effectiveness is quite limited, and essentially all prevention interventions focus at the individual level. This review was able to find only one published article describing evidence-based interventions to promote cancer screening and improve cancer treatment in people with mental illness. Based on our review of the literature and the experience and expertise of the authors, we conclude each section with suggestions at the individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy level that may improve cancer prevention, screening, and treatment in people with mental illness.

Keywords: epidemiology, health disparities, prevention, screening, early detection

1. Introduction

Mental illness and health disparities

Despite the high prevalence of mental illness among adults, only in the last decade has this population been recognized as experiencing significant health disparities, including both increased morbidity and mortality.1,2 Mental illness is exceedingly common, with Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration statistics indicating almost 44 million adults (18.6%) had any mental illness in the last year, and of those, almost 10 million (4.1%) had a serious mental illness (SMI).3 Individuals with SMI - defined as a mental illness such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder that results in substantial functional impairment4–are particularly likely to experience significantly reduced life expectancy. A report by Parks et al (2006) raised national awareness by stating that people with SMI die decades earlier in our country, when compared to the general public2,5,6 Most of this disparity is related to preventable and treatable chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer,7 with studies finding that, similar to the general population, cancer is the second leading cause of death.1,8 Multiple factors contribute to this excess morbidity and mortality including behavioral and lifestyle factors, socio-environmental circumstances, and access to and quality of medical care.9 However, more attention has been focused on promoting change on an individual level with less emphasis on the contextual inequities (e.g., food environments, poverty, discrimination) that drive much of the disparities.10,11

Mental Illness & Cancer

The evidence to date from epidemiologic studies regarding mental illness and cancer is now abundant, complex, and conflicting. Reports regarding cancer incidence are particularly inconsistent, with studies finding the risk of cancer among individuals with mental illness to be higher, lower, or equivalent to that of the general population.12–30 A recent study comparing a state Medicaid cohort with SMI to the general US population revealed that total cancer incidence was 2.6 times higher in the SMI cohort.22 In contrast, studies such as Ji et al. (2013) reviewed a large Swedish cohort of people with schizophrenia and their first-degree relatives and found an overall decreased incidence rate of cancer in both people with schizophrenia and their first degree relatives.18 Adding to this complexity, findings tend to differ (but not necessarily in consistent directions) depending on whether studies control for behavioral risk factors, such as smoking, or whether they stratify by sex. For example, even within single psychiatric diagnostic categories, cancer risk patterns vary, with researchers noting, the potential for schizophrenia to serve as a protective factor for cancer15,25,24,17 as well as a risk.21 Indeed, comparing studies with differing approaches to controlling for confounding serves to highlight the critical impact of multiple behavioral and environmental risk factors in this population. In reality, the very issue of health disparities in this population is most likely due to the prevalence of modifiable risk factors.7,9 A deeper understanding of the upstream contribution to these risk factors provides the opportunity to develop more effective interventions and reduce health disparities.

Overall, studies of incidence vary widely along many dimensions. This provides a multitude of rich data, but exacerbates the lack of consensus regarding the link between mental illness and cancer incidence, leading some researchers to conclude, “the epidemiological puzzle remains unsolved.”29,p339 Others, however, suggest that higher quality studies (reflected by larger study samples, greater numbers of overall cases, and longitudinal data with higher person years of follow-up) provide a more consistent picture of higher risk, for example among persons with schizophrenia for breast cancer.31 Nevertheless, studies consistently find that cancer accounts for much of the disease burden of individuals with mental illness. For example, a large prospective study of patients with schizophrenia revealed an all cause death rate nearly 4 times higher than the general population, with cancer as the second most common cause of death after suicide, and before cardiovascular disease.8

In contrast to the cancer incidence findings, many recent studies report increased cancer mortality rates in people with mental illness.32,8,33,34 While the evidence is not unequivocal, findings more consistently point to a higher standardized mortality ratio within SMI populations.8,35,36 A variety of factors may contribute to higher mortality, including more advanced stage at presentation due to delayed diagnosis, co-morbidities that complicate treatment (including psychotropic and oncology drug interactions), poorer quality care, and reduced access to specialized treatment.37

While individual lifestyle factors, such as smoking or poor adherence to treatment, play a significant role in shaping risk among persons with mental illness, many contextual or systems-level factors exacerbate these individual factors. These contextual factors including lack of integration between mental health and medical care systems (as well as the complexity of navigating them), mental illness stigma and physician bias, as well as social circumstances (e.g., lower education, income, and social integration; greater unemployment, homelessness, and overall poorer quality housing and neighborhoods)1,2,5 may fundamentally drive health disparities among people with SMI. Were it indeed the situation that cancer incidence is no greater in people with SMI, but case fatality is higher, the higher prevalence of commonly known cancer risk factors, such as tobacco use and obesity, is less likely to explain the higher mortality rates.38 This multitude of factors contributing to cancer risk among people with SMI presents a research and clinical challenge, but also multiple opportunities for intervention as well as a call to action. This underserved and vulnerable population confronts a particularly challenging set of obstacles to receiving high quality care for all diseases, including cancer. Both understanding and modifying risk of cancer in people with serious mental illness and overcoming barriers to care define important public health and social justice goals. The purpose of this review is to evaluate and synthesize the available data in prevention, screening, and treatment of cancer in people with serious mental illness in order to provide further reconceptualization of this complex topic and provide a pragmatic approach to clinical care. We propose a modification of the ecological model as the underlying theoretical framework for this review in order to highlight the multiple contributing factors and points of intervention.

Theoretical framework

There are many “ecological models” or multi-level frameworks designed to explicate the multiple levels that can affect health and health behavior.39,40,41 To a certain extent, these models arose in response to interventions focused at the individual level, which conceptualized health as largely determined by individual characteristics or attributes, with individuals bearing primary responsibility for health outcomes. These individual-level interventions have been criticized by some as “blaming the victim”41,42 and can be particularly problematic for marginalized and stigmatized populations, such as those with experiences of mental illness, since they often fail to acknowledge the overwhelming environmental and societal barriers to good health.

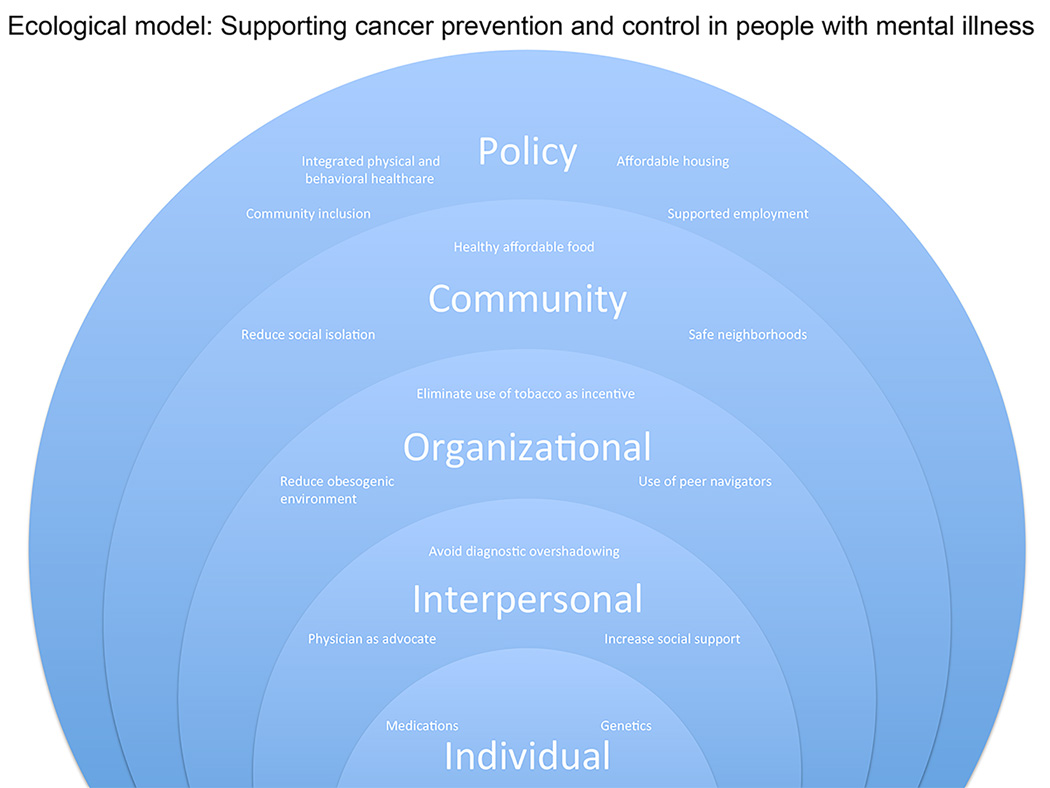

McLeroy is generally credited with the development of the well-known “Social Ecological Model,” (SEM) in his seminal piece, “An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs” (even though he himself did not use the term “social ecological model”).41 As originally articulated, McLeroy’s SEM views health behavior as being determined on five levels: (1) Intrapersonal factors-characteristics of the individual such as knowledge, attitudes, behavior, self-concept, skills, etc. This includes the developmental history of the individual; (2) Interpersonal processes and primary groups-formal and informal social network and social support systems, including the family, work group, and friendship networks; (3) Institutional factors-social institutions with organizational characteristics, and formal (and informal) rules and regulations for operation; (4) Community factors-relationships among organizations, institutions, and informal networks within defined boundaries, and (5) Public policy-local, state, and national laws and policies.41

As demonstrated by epidemiological studies, cancer incidence and outcomes can be affected on many levels by competing factors. Some factors, such as genetics, have been theorized to either increase or decrease,17 the risk of cancer in people with schizophrenia. Similarly, antipsychotic medications may have anti-tumor properties, but they may also contribute to risk of cancers such as breast and endometrial, which are hormonally regulated.42 Some behaviors, such as smoking and low physical activity, contribute to increased risk of many cancers,2 while low exposure to sunlight in institutional settings may decrease risk of skin cancer.26 Health system issues can also be protective or harmful; for example, mental health agencies that facilitate healthcare for their population can result in increased rates of detection and treatment,44,45 while the stigma encountered in the general medical system almost certainly contributes to increased morbidity and mortality.17 Using this multi-level framework(Figure 1), this paper reviews cancer prevention, screening, and treatment among populations with mental illness, with special emphasis on disparities and potential underlying mechanisms. Each section concludes with recommendations for clinical practice in each area. Additionally, Table 3 provides a summary of key recommendations for medical clinicians to improve cancer prevention screening and treatment in people with mental illness. As the following synthesis will demonstrate, evidence supporting effective interventions is quite limited. Therefore, the clinical practice recommendations are based on a combination of evidence and the experience and expertise of the authors.

Figure 1.

Ecological model: Supporting cancer prevention and control in people with mental illness

Table 3.

Selected Studies From Narrative Reviewa

| CANCER SCREENING AND TREATMENT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CANCER TYPE/ PRIMARY AUTHOR |

MH DX | STUDY DESIGN |

DATA COLLECTION/METHODS | SAMPLE AND SETTING |

RESULTS/DATA | CONCLUSIONS |

| Breast/Mitchell 201454 | M | SRMA | Review of literature examining whether women with a mental illness are less likely to receive mammography screening |

Multiple | Significantly reduced rates of mammography screening in women with mental illness (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.66–0.77), mood disorders (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76–0.90), and particularly SMI (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.45–0.65) |

Mammography rates are lower in women with mental illness, especially SMI |

| Breast, cervical/ Aggarwal 201355 |

M | SR | Systematic review of health disparities in breast and cervical cancer screening among women with mental illness |

Multiple studies | In total, 19 studies were included; the most commonly discussed facilitator was a relationship with a primary care physician |

Breast and cervical cancer disparities persist among women with chronic mental illness, although this population is complex and diverse |

| Breast, cervical, colon/ Happell 201256 |

M | Review | Narrative review to examine disparities in preventive health care for cancer and infectious diseases among individuals with SMI |

Multiple studies | Individuals with SMI generally had lower screening rates, with 20% to 30% lower receipt of screenings for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers |

The majority of evidence demonstrates poorer quality of preventive services for individuals with SMI compared with the general population |

| Breast, colon/Druss 201057 | M | RCT | Trial comparing medical care management for individuals with SMI vs usual care |

N 5 407 patients in CMHC in Atlanta, Georgia |

At 12-mo follow-up, the intervention group received an average of 58.7% of recommended preventive services compared with 21.8% in the usual care group (P < .001) |

Care management was associated with significant improvement in primary care process and outcome measures |

| Cervical/Weitlauf 201358 | D, PTSD | O | Study comparing receipt of recommended cervical cancer screening in 3 diagnostic groups: 1) PTSD, 2) depression, and 3) no psychiatric diagnosis |

N 5 34,213 women from the national VA database |

Overall, 77% of women with PTSD, vs 75% of those with depression and 75% of those without psychiatric illness, received cervical cancer screening during the study observation period (P < .001) |

VA health care environment may “level the playing field” for those with psychiatric illness |

| Cervical/Abrams 201259 | M | CC | Case-control study comparing rates of cervical cancer screening and acute care visits among women with and without a diagnosis of mental illness |

N 5 105,681 female Maryland Medicaid enrollees |

There was increased cervical cancer screening in women with psychosis (OR, 1.46), bipolar disorder/mania (OR, 1.59), and depression (OR, 1.78) and decreased OR for women with substance use (OR, 0.8) |

People within the Maryland Medicaid system with mental illness appear to be able to access preventive care; more outreach is needed for women with substance use |

| Multiple/Barley 201360 | M | SR | Systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to encourage cancer screening in adults with SMI |

Multiple | There is no evidence for any method of increasing cancer screening specifically for people with mental illness |

Evidence-based approaches to increasing cancer screening in individuals with SMI are greatly needed |

| Multiple/Irwin 201461 | S | Review | Review of health disparities in cancer care among patients with schizophrenia |

Multiple | Patients with schizophrenia are less likely to have up-to-date cancer screenings |

Patient-level, provider-level, and systems-level factors contribute to low rates of cancer screening; psychiatrists can facilitate screening |

| Breast/Rahman 201462 | M | Review | Review article on pathophysiology, clinical implications, and pertinent preclinical data regarding the use of anti- psychotics in patients with breast cancer |

Multiple studies | Prolactin promotes breast cancer cell growth regardless of receptor status, and breast cancer patients with elevated prolactin levels have quicker disease progression and lower survival rates; most first-generation antipsychotics significantly elevate serum prolactin levels |

A decision to discontinue or change medications requires consideration of the risks and benefits given the patient’s mental illness type and severity, cancer staging, and patient and family preferences |

| Breast/Sharma 201063 | S | O | Cohort study of breast cancer treatment in women with schizophrenia from 1993 to 2009 |

N 5 90,676 patients from UK NHS records |

Thirty women (81%) presented with early breast cancer, and 7 (19%) presented with metastatic disease; treatment outcomes, trial involvement, compliance, and ability to provide informed consent were similar to previously published cohort data |

Schizophrenia does not affect treatment delivery or outcomes in women with breast cancer; the presence of schizophrenia should not be a limiting factor for entry into clinical trials |

| Colon/Baillargeon 201164 | M | O | Retrospective review of SEER- Medicare–linked data on all individuals diagnosed with colon cancer between January 1, 1993, and December 31, 2005 |

N 5 8670 participants aged 67 y and older with a diagnosis of colon cancer in the SEER- Medicare database |

Participants with mental illnesses were more likely to have been diagnosed with colon cancer at autopsy (4.4% vs 1.1%; P < .001) and with an unknown stage of cancer (14.6% vs 6.2%; P < .001); to have received no surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy (ARR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.86– 2.35); and to have received no chemotherapy for stage III cancer (ARR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.49–1.79) |

Public health initiatives are needed to improve colon cancer detection and treatment in older adults with mental disorders |

| Lung/Bergamo 201465 | S | O | Retrospective review of SEER- Medicare–linked data from patients aged 66 y or older with confirmed, primary NSCLC diagnosed between 1992 and 2007 |

N 5 96,702 patients with NSCLC in SEER- Medicare database |

Patients with schizophrenia were less likely to present with late-stage disease, undergo appropriate evaluation, or receive stage-appropriate treatment (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73–0.93; P < .050 for all comparisons; OR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.43–0.58); survival was decreased among patients with schizophrenia, although not after controlling for treatment received |

Elderly patients with schizophrenia present with earlier stages of lung cancer but are less likely to undergo diagnostic evaluation or to receive stage-appropriate treatment, resulting in poorer outcomes |

| Multiple/Foti 200566 | M | O | Study of treatment preferences in response to hypothetical medical illness scenarios |

N 5 150 community- residing adults with SMI in Massachusetts |

For the scenario involving pain medication for incurable cancer, most participants chose aggressive pain management, even if cognition might be affected; few participants thought a doctor should provide patients with enough medication to end their life; for the scenario of irreversible coma, respondents were divided in their choice regarding life support |

Persons with SMI were able to designate treatment preferences in response to EOL health state scenarios; although most participants had not previously participated in advance care planning, they were interested in the topic and participated |

| Multiple/Howard 201044 |

M | Review | Review of multiple articles looking at SMI and cancer incidence and risk factors, screening, and equity of access to treatment and care |

Multiple studies | Patients with SMI are less likely to receive cancer screenings; there is insufficient evidence to determine whether unique barriers exist for individuals with SMI; for treatment, patients with SMI have poorer access to diagnostic and treatment services for health complaints and have delays in help seeking; are less likely to receive surgery for esophageal cancer; have more treatment complications; and have higher case-fatality rates for multiple cancers |

Severe mental illness is associated with behaviors that predispose an individual to an increased risk of some cancers, disparities in screening for cancer, and higher case-fatality rates; inequalities in care need to be addressed by all health care professionals involved, including those from mental health services and the surgical and oncology teams |

| Multiple/Damjanovic 200643 |

S | Review | Review of behaviors that increase the risk of cancer in patients with schizophrenia |

Multiple studies | Some antipsychotics increase prolactin, which may increase breast and endometrial cancer risk; studies of overall malignancy risk have conflicting results; some psychotropic drugs can inhibit chemotherapy metabolism |

Treatment of cancer in individuals with schizophrenia should include evaluation of risk factors, drug interactions, risk-benefit analysis of treatment options, and efforts to promote treatment adherence |

| Multiple/Damjanovic 200643 |

S | Review | Review summarizes known disparities in cancer prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and EOL care among individuals with schizophrenia |

Multiple studies | Patients with schizophrenia have delays in diagnosis and treatment, perhaps due to stigma; are less likely to have esophageal or colorectal cancer surgery; have higher postsurgery mortality and postoperative complication rates; and are less likely to participate in clinical trials |

Providers should assume decisional capacity and address suicidality, violence, and homelessness |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; ARR, adjusted relative risk; ART, adjuvant radiation therapy; BMI, body mass index; CC, case-control; CI, confidence interval; CMHCs, Community Mental Health Centers; D, depression; DX, diagnosis; EOL, end of life; M, multiple mental illnesses; MA, meta-analysis; MH, mental health; NAEs, neuropsychiatric adverse events; NSCLC, nonsmall cell lung cancer; O, observational; OR, odds ratio; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; RR, relative risk; S, schizophrenia; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; SMI, serious mental illness; SR, systematic review; SRMA, systematic review and meta-analysis; UK NHS, United Kingdom National Health Service; VA, Veterans Affairs.

A more complete version of Table 3 is provided in Supporting Tables 1 through 3 (see online supporting information)

Materials and Methods

We conducted an integrative review in order to summarize the empirical literature on cancer prevention, screening, and treatment for people with mental illness. An integrative review differs from meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which generally combine evidence from a group of studies using a statistical or quasi-statistical approach to answer a particular question. Integrative reviews summarize evidence from studies with diverse methodologies (e.g., experimental and non-experimental studies) to synthesize the state of the science in a specific topic to guide evidence-based care.46,47 The topic of this manuscript is broad and there is a significant lack of randomized controlled trials, especially in screening and treatment. Because of the complex issues facing the population and the clinicians who care for them, an integrative review provides a unique opportunity to synthesize multiple levels of evidence and opinion in order to provide practical guidelines for approaching these issues.

Description of search strategy

An experienced research librarian assisted LCW and KEH to develop a list of terms and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) that were searched in the following databases: 1) PubMed, 2) Scopus, 3) the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and 4) psychINFO. Table 1 lists the search terms and limits for each database. We searched for articles that were published between 2005 and 2015, to coincide with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration’s (SAMSHA) national call to action to improve health and wellness in people with mental health and substance abuse disorders.48 We considered all study designs (including experimental, quasi-experimental, non-experimental, and qualitative studies), editorials, and reports. However, to be included in the review, articles needed to have a specific focus on populations whose mental illness preceded the diagnosis of cancer. We excluded case reports, articles focusing only on cancer survivors, and articles that did not clearly specify pre-morbid psychiatric disease. To simplify the search strategy, we conducted separate searches for “prevention” “screening” and “treatment.” Search terms and results are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Key Recommendations for Medical Clinicians to Improve Cancer Prevention, Screening, and Treatment in People with Mental Illness

| Prevention: Addressing obesity and tobacco use |

| Strongly consider metformin for weight loss in people with schizophrenia and obesity or rapid weight gain |

| Actively address tobacco dependence in all people with mental illness and consider bupropion and varenicline in psychiatrically stable patients |

| Screening |

| Provide a community health worker or peer counselor to help the patient navigate the screening process |

| Increase awareness of cancer screening in mental health service providers |

| Treatment |

| Consciously avoid the tendency towards “diagnostic over shadowing,” or attributing physical symptoms that may indicate cancer to the patient’s mental illness. |

| Involve staff from community-based social supports, who often have long-term relationships with patients, early in the diagnostic and treatment process |

| Engage people with mental illness in end-of-life treatment decisions |

We also undertook hand searches of reference lists of relevant literature reviews. In total, 82 articles were identified using this approach. Authors LW, AS and AC reviewed articles and systematically abstracted article information into databases that summarized data collection and methods, sample and setting, results/data, and conclusions. The majority of articles reviewed were cross-sectional studies (34%), randomized controlled trials (18%), or non-systematic reviews (11%). (See Table 2)

TABLE 2.

Example of Search Terms Using PubMed Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) Terms

| Prevention/risk factors |

| Schizophrenia, disorders with psychotic features, mood disorders, neoplasm, prevent*, chemoprevent*, chemoprophyla*, “prevention and control,” risk factors |

| Prevention/tobacco cessation |

| Schizophrenia, disorders with psychotic features, mood disorders, neoplasm, tobacco use cessation |

| Prevention/weight management |

| Schizophrenia, disorders with psychotic features, mood disorders, neoplasm, prevent*, “prevention and control,” exercise, overweight, body weight changes |

| Screening |

| Schizophrenia, disorders with psychotic features, mood disorders, neoplasm, “early detection of cancer,“ “cancer early detection,” “cancer screening,” “cancer early diagnosis,” Papanicolaou test, mammography, colonoscopy |

| Treatment |

| Schizophrenia, disorders with psychotic features, mood disorders, neoplasm, treat*, “clinical trial,” “random allocation,” “randomized controlled trial,” “antineoplastic protocol,” “cancer treatment protocol,” “antineoplastic combined chemotherapy protocols” |

Synthesis of findings

Prevention and risk factors

This section reviews interventions intended to decrease cancer risk in people with mental illness, with a specific focus on overweight/obesity and tobacco use, which are leading causes of cancer cases in this population. Up to one-third of cancer cases in economically developed countries are related to overweight or obesity, physical inactivity, and/or poor nutrition.49 People with a current mental illness are almost twice as likely to be obese compared to those without a mental illness.50 An exacerbating factor is that up to 80% of people taking anti-psychotic medication experience antipsychotic induced weight gain.51 Further, mainstream weight loss interventions often do not address the numerous challenges faced by this population, including limited financial and social resources, and stigma.

Similarly, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality in the US and tobacco use accounts for at least 70% of all lung cancer deaths, and at least 30% of ALL cancer deaths.52 People with a current mental illness are more than twice as likely to smoke cigarettes compared to those without a mental illness.53, Prevalence estimates for smoking range from 70–85% for people with schizophrenia and 50–70% for people with bipolar disorder.54,55 Additionally, people with schizophrenia smoke more heavily, have more severe nicotine dependence, and have lower quit rates compared to the general population.56 Smoking disparities are also evident in rates of quitting tobacco use and an analysis of smoking trends from 2004–2011 indicated that smoking rates among people with mental illness declined very minimally.57

The underlying causes for higher rates of obesity and tobacco use in people with mental illness are complex and interact on multiple levels. Among them are exposure to chronic stressors (e.g., stressful living environments triggering tobacco use and unhealthy eating habits), few financial resources (e.g., difficulties paying for tobacco treatment interventions or healthy food options), medication side-effects (e.g., directly leading to weight gain or triggering tobacco use to mask side effects), and “therapeutic nihilism” (e.g., providers’ doubting individuals’ abilities to engage in behavior change). Recognizing these alarming statistics, a significant number of obesity treatment/prevention and tobacco cessation intervention are being tested in populations with SMI.

Obesity related interventions

In 2006, the National Institute of Mental Health released a meeting report which concluded that empirically-based interventions to address obesity in people with mental illness was not receiving adequate research attention.58 Since that time, many studies have been conducted on this topic. Interventions addressing obesity among persons with mental illness concentrate on two approaches: general interventions to promote weight loss as well as interventions to reduce anti-psychotic use weight gain. These interventions can be behavioral, pharmacological, or both.

There have been at least eight systematic reviews in the last decade looking at behavioral interventions to promote weight loss in people with SMI.,59–64,88,91,including a recent Cochrane review.64 For the most part, these interventions consisted of group or individually based programs promoting changes in diet and/or physical activity without elements of cognitive and/or behavioral modification. All reviews noted issues with study design, methodological rigor, and reporting of statistically significant, but clinically insignificant weight loss (i.e., less than 5%–7% of initial weight). A notable exception is Daumit and colleagues’ (2013) 18-month tailored behavioral weight-loss intervention in adults with SMI which reported that 37.8% of people in the intervention group achieved statistically and clinically significant weight loss as compared with 22.7% of those in the control group (P=0.009).87 This study was unique in that the weight loss program lasted 18 months, whereas the programs in other trials were generally less than 6 months. Based on their results, the authors hypothesized that perhaps “persons with serious mental illness take longer than those without serious mental illness to engage in an intervention and make requisite behavioral changes.”87 Similarly, Bartels59 notes in his review that more successful programs tended to be of longer duration and included both education and activity-based approaches, similar to findings in the general population.

The data regarding the use of pharmacological agents for weight loss or prevention of weight loss, particularly metformin, are similarly limited. A recent randomized controlled trial in the Veterans Administration health system found that metformin was modestly effective in reducing weight in clinically stable, overweight outpatients with chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder over 16 weeks.97 Like many other studies, however, it showed statistically significant weight loss, but not clinically significant weight loss, though findings suggested that benefits of metformin may continue with longer treatment.97 On a more encouraging note, an RCT by Wu et al104 specifically targeted weight gain in the context of first episode psychosis. Significantly fewer patients in the olanzapine plus metformin group increased their baseline weight by more than 7%, (which was the cutoff for clinically meaningful weight gain), as compared to patients in the olanzapine plus placebo group. This study and other studies in the general population,105 suggest that metformin maybe more effective in younger populations.

Given these findings, Hasnain concluded in his 2011 review that metformin therapy should be considered in 3 high risk groups: 1) obese patients with schizophrenia and evidence of glucose dysregulation, irrespective of antipsychotic drug treatment; 2) obese patients with schizophrenia and without current evidence of glucose dysregulation, but with a strong family history of diabetes; and 3) young adults with schizophrenia newly exposed to antipsychotic drugs who show a pattern of rapid weight gain and/or glucose dysregulation.95 Other pharmacological agents have been considered for use in weight management in patients taking antipsychotic drugs, including amantadine, reboxetine, sibutramine, and topiramate. However, there is less data for these agents and all can have significant side effects (such as gastrointestinal side effects) especially for people with mental illness taking other medications.93

Medication associated-weight gain is also a common clinical concern in patients with depression. Contributing factors include increased use of anti-psychotic medication in treatment-resistant depression and ongoing questions regarding the effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on weight. In the most comprehensive study to date, Blumenthal et al. (2014) reported that when compared with citalopram (and other SSRIs), individuals treated with bupropion, amitriptyline, and nortriptyline had a significantly decreased rate of weight gain. However, the 12 month weight gain associated with citalopram was quite modest at 1.2 kg (SD +/− 5.3 kgs) with 16% of patients showing a weight gain greater than 7%.106

A recent qualitative study explored the contexts and barriers to health in people with SMI and remarked on “unhealthy local environments” including lack of available healthy food and safe places to exercise, as well as the preponderance of fast food.11 Notably, very few interventions were identified that addressed the “obesogenic environment” in which many people with mental illness live, as well as the challenges they face given their limited financial resources. A novel pilot RCT by Jean-Baptiste et al (2007) is a notable exception. In addition to a 16-week behavioral modification and physical activity curriculum, participants in the intervention group were provided with a specific listing of healthy foods they could purchase, for which they would be reimbursed up to twenty-five dollars a week. The weekly reimbursement reinforced health food purchasing and at the same time served as a financial incentive for attendance. Participants in this pilot showed non-clinically significant weight loss, but remarkably, weight loss continued 6-months after the intervention.107 However, even this study was an individually focused intervention and did not address higher level issues in the “obesogenic environment.” In summary, the current data regarding weight management for people with mental illness is limited, with promising interventions by Daumit et al(2013)87 and Wu et al (2008).104 Additional intervention studies are underway, such as that by Cabassa et al, examining the use of a peer-led group lifestyle modification program supportive housing agencies that provide both housing and individualized support services to people with SMI.108

Tobacco related interventions

While multiple studies indicate that people with SMI want to quit smoking,55,109,78, 110 effective treatment is underutilized and there is a lack of population-specific smoking cessation programs.110 People with SMI may require specialized smoking cessation programs because of the complex interplay of social, psychiatric, and genetic factors that contribute to their high smoking rates. As in the general population, smoking cessation efforts for people with mental illness include some combination of behavior modification, nicotine replacement, and pharmacological therapy (buproprion or varenicline).

The data on use of NRT only is limited by heterogeneity of trials and short follow-up periods.56 A potentially promising approach in this population is treatment with off-label high dose NRT (greater than one 21mg patch). One small study compared high dose NRT (42mg) vs regular dose (21mg) in people with schizophrenia and found that high dose NRT was well tolerated, although the study failed to find a significant difference in abstinence rates between the 2 groups.83 A single arm study by Selbey et al. (2013) of people with psychiatric comorbidities using escalating doses of NRT found significant reductions in both cigarettes per day (mean decrease, 18.4 ± 11.5) confirmed by expired carbon monoxide (mean decrease, 13.5 ± 13.0) with no significant changes in plasma nicotine concentrations during the course of NRT dose titration. In this study, the mean NRT dose was 32.7 (SD, 16.4) mg/d (range, 7–56 mg/d).77

The use of bupropion and varenicline in this population has been limited by theoretical and reported concerns of adverse neuropsychiatric events, including suicide, and initial safety studies did not include people with mental illness. The Federal Drug Administration has required a black box warning regarding the risk of serious adverse psychiatric events for both buprorion andvarenicline.111 Two Cochrane reviews recently examined studies involving pharmacological smoking cessation interventions among people with schizophrenia56 and depression.112 Tsoi’s review confirms the importance of pharmacological therapy with bupropion to achieve tobacco cessation for people with schizophrenia.56 Van der Meer’s report, however, produced mixed findings, concluding that use of bupropion may increase long-term cessation in smokers with past depression, but paradoxically, there was no evidence to support the use of bupropion in smokers with current depression.67 All trials with bupropion monitored participants’ mental health during treatment and none reported adverse effects.

With respect to varenicline, Gibbons and Mann (2013) reviewed data from randomized controlled trials and from a large Department of Defense (DOD) observational study to assess its efficacy. Their review of the evidence offered significant support for the superior efficacy of varenicline relative to both placebo and bupropion, in individuals with and without a recent history of a psychiatric disorder. With respect to safety, their review revealed no indication that varenicline is associated with adverse neuropsychiatric events,75 and, in a corresponding editorial, Evins (2013) stated “Varenicline doubles to triples the likelihood of quitting smoking over placebo, and its most common side effects are nausea and vivid dreams…it is time to unring the alarm bell on varenicline and use this effective medication on a larger scale”.72,p1385

In contrast, another study assessed neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with varenicline, and using a method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions, concluded that varenicline was responsible for probable causality in 76% of cases and definite causality in 12% of cases.68 Though that study was limited to 25 reports of adverse events, the possibility of adverse psychiatric events with varenicline cannot be ruled out. Pfizer is currently completing a phase 4, randomized, double-blind, active and placebo-controlled, multicenter study evaluating the neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of 12 weeks varenicline tartrate 1 mg bid and bupropion hydrochloride 150 mg bid for smoking cessation in subjects with and without a history of psychiatric disorders. Results are expected to be released in the 3rd quarter of 2015. This will provide very helpful further guidance for clinicians.73

In terms of treatment complications among people with mental illness, clinicians need to be aware of potential changes in metabolism of certain psychotropic medications with reduced smoking. Smoking substantially lowers blood levels of numerous antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol, fluphenazine, chlorpromazine, thioridazine) as well as multiple other medications, by increasing cytochrome P450 metabolism. People who successfully cut down or quit potentially need significantly lower doses of these medications.113 Importantly, tobacco cessation in people with SMI needs to address the organizational environment of mental health agencies that use cigarettes as incentives and have high levels of staff tobacco use. One promising model is the “Addressing Tobacco Use Through Organizational Change” or ATTOC model currently being tested by Dr. Ziedonis and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts.114

Obesity and Tobacco Recommendations

The following section outlines multi-level recommendations for addressing obesity and tobacco use in people with mental illness

Individual level

- Strongly consider metformin therapy for weight loss in three high-risk groups:95

-

◦Obese people with schizophrenia with evidence of glucose dysregulation, irrespective of antipsychotic drug treatment;

-

◦Obese people with schizophrenia without current evidence of glucose dysregulation but with a strong family history of diabetes;

-

◦Young adults with schizophrenia newly exposed to antipsychotic drugs who show a pattern of rapid weight gain and/or glucose dysregulation

-

◦

Actively address tobacco dependence in all people with mental illness and consider bupropion and varenicline in psychiatrically stable patients

Monitor need for decreased doses of medications in people who decrease smoking

Consider the promotion of healthy lifestyle and physical activity interventions in all people with mental illness.86,87

Organizational level

Increase efforts to reduce obesogenic environments in agencies that serve people with mental illness, such as increasing structured opportunities for physical activity and providing healthier meals and snacks.

Eliminate the use of tobacco and unhealthy food as incentives in mental health treatment agencies

Support smoke-free environments in mental health treatment agencies

Deliver health interventions in community settings that regularly serve people with SMI, to address access barriers

Include healthy lifestyle goals in treatment planning for people with mental illness

Community level

Increase efforts to reduce obesogenic environments in low-income neighborhoods, where people with SMI are more likely to reside, by partnering with community agencies to advocate for farmer’s markets, super markets, and access to safe spaces for physical activity

Policy level

Increase funding for high quality, multi-level intervention trials addressing obesity and tobacco use in people with mental illness

Provide insurance reimbursement for the screening, management, and treatment of obesity and tobacco cessation programs as part of mental health treatments

Screening

Studies generally show lower rates of cancer screening in people with schizophrenia or psychosis,131,121,133,134,124 even in systems providing free access to screening services. However, these studies are all either retrospective cross-sectional or case-control studies. The majority focus on breast and cervical cancer screening, with a few considering colorectal cancer screening. The available data for women with depression is mixed, with essentially equal numbers of studies showing decreased rates,122,129 or no differences in breast and cervical cancer screening,123,130 and conflicting results for rates of colon cancer screening.128,133 Several studies note that women with depression access the healthcare system more frequently, and therefore in some settings, they may be offered more opportunities for preventive services. Weitlauf et al’s (2013) finding of equal rates of cervical cancer screening in women veterans with depression and women veterans without a psychiatric diagnosis, suggests that the VA healthcare environment may "level the playing field" for those with psychiatric illness.130,p. e157 Despite this conflicting evidence, a systematic literature review of cancer screening in women concluded that “lower cancer screening utilization persists across the spectrum of mental illness diagnosis and severity,” and noted that studies finding no differences were often limited by small, or less representative, samples.138

Notwithstanding the documented disparities, few interventions exist to increase screening rates for persons with SMI and, disappointingly, a recent Cochrane review found “no RCT evidence for any method of encouraging cancer screening uptake in people with SMI.”139,p1 However, one RCT not mentioned in the Barley review was the Primary Care Access Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) Study by Druss et al. (2010). In this study, nurse care managers followed a manualized or standardized semi-structured protocol to improve use of preventive and primary care services in people with SMI. At 12-month follow-up, the intervention group received an average of 58.7% of recommended preventive services, compared to 21.8% in the usual care group (p<0.001). While cancer prevention and screening services were not reported individually, mammography and sigmoid screening were included as measures of preventive care.140 Additionally, two of the authors (LW and KH) have recently developed a shared-decision making and navigation intervention to increase breast cancer screening uptake in women with SMI. A six-month pilot study of this intervention with 22 formerly homeless women with SMI who were not up to date on mammography screening was recently completed. Sixty-six percent of women completing the study reported receiving a mammogram, and there was a significant decrease in decisional conflict immediately post intervention, which was maintained at the 6 months follow-up.141

Screening recommendations

The following section outlines multi-level recommendations to promote cancer screening in people with mental illness

Individual level

Provide sensitive cancer screening environments for people with mental health issues that allow for limited wait times and orientation to equipment and procedures

Interpersonal level

Consider using and adapting shared decision-making tools for people with mental illness to increase engagement in prevention activities

Provide a community health worker or peer counselor to provide health education and help the patient navigate the screening process

System level

Increase awareness of cancer screening disparities among mental health service providers

Increase integration of primary and behavioral health services with an emphasis on screening and prevention

Decrease complexity of obtaining screening services

Promote programs to educate peer counselors (specially trained lay people with personal experience of mental illness) in prevention and wellness to deliver services.

Policy level

Advocate for enhanced reimbursement for interdisciplinary care coordination and preventive care services in people with complex medical and psychiatric morbidities

Treatment

The majority of studies of cancer treatment in individuals with SMI have focused on individuals with cancer and schizophrenia or major depression;142–147,149–151,153–155 several have examined cancer treatment across multiple psychiatric conditions.148,157 To date, this research has been observational and cross-sectional. These studies reveal numerous disparities for patients with SMI and cancer in diagnosis and time to treatment, receipt of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery; and clinical trial participation. Evidence of disparities is particularly strong for individuals with schizophrenia and other conditions that include psychosis.

One important barrier to achieving optimal cancer outcomes is delayed diagnosis. A study of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)–Medicare linked data showed that individuals with mental illness (defined as mood disorders, psychotic disorders, dementia, substance abuse and dependence disorders, and other) and colon cancer are more likely to have un-staged colon cancer or diagnosis of colon cancer at autopsy.148 Another SEER-Medicare analysis revealed that patients with schizophrenia and non-small cell lung cancer are less likely to have appropriate evaluation.151 A study of Swedish adults with schizophrenia who died of cancer showed that those individuals were less likely to have a cancer diagnosis prior to death.37 One examination of women with major depression or anxiety in six Boston-area health centers found no association between these diagnoses and time to resolution of abnormal mammogram or Pap test results.147

In general, patients with SMI, particularly schizophrenia, are less likely to receive appropriate chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or surgery. A study in Western Australia, with a dataset consisting of over 100,000 new cancer cases, found that individuals with mental illness received fewer sessions of chemotherapy in general and were less likely to receive surgery overall, as well as radiation therapy for certain cancer sites.38 Other studies similarly found that patients with a major mental illness are less likely to receive chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery for colon cancer,148 and are less likely to have surgery for oral cancer.157 Individuals with schizophrenia are less likely to receive stage-appropriate treatment for lung cancer,150 surgery for esophageal cancer,137 and referrals to clinical trials.137 There are a few exceptions to this pattern of treatment disparities, most notably for chemotherapy rates among breast cancer patients with schizophrenia.145,146,137

Those with SMI are more likely to have treatment complications and poorer outcomes. Women with psychiatric diagnoses undergoing mastectomy are more likely to have complications and longer hospitalizations.143 A study of women with Stage 0-II breast cancer found that those with a history of major depressive disorder had greater declines in physical functioning than those with no history of depression.142 Patients with schizophrenia have a higher rate of post-operative complications and post-surgery mortality.137 Finally, as previously noted, many studies have found that individuals with SMI have disproportionately higher cancer mortality rates.148,151,157, 37,44,137

Patient-, provider-, and systems-level factors all contribute to these disparities in diagnosis, treatment and outcomes. Patient-level factors include delays in help-seeking due to mental health symptoms, such as the disorganized thoughts, paranoia, and decreased pain sensitivity associated with schizophrenia.137 Increased prevalence of health risk behaviors and comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease can complicate treatment and contribute to poorer outcomes.150,38,44 Fragmented primary, oncology and mental health services,154 providers’ stigmatizing beliefs or behaviors153 and “diagnostic overshadowing” - when clinicians misattribute physical symptoms to a mental illness rather than, correctly, to a physical illness – may also delay appropriate diagnosis and treatment, especially for individuals with schizophrenia and other SMI.44,137

Once diagnosed, patients often face perceptions that they are “difficult patients” who lack the capacity to make treatment decisions or adhere to treatment regimens or may become violent.44,,137,145 Barriers to clinical trial enrollment include patients’ mistrust of research, lack of communication to patients about relevant trials, and concerns about patients’ ability to provide informed consent, which has resulted in outright exclusion of people with SMI in many of these studies.137 Finally, individuals with SMI are more likely to experience social isolation,158 poverty,148 and homelessness,155 all of which present numerous challenges to providing treatment and end-of-life care.137

Treatment Recommendations

The following section outlines multi-level recommendations for improving cancer treatment in people with mental illness

Individual level

Patients with SMI may benefit from a brief hospitalization after their first chemotherapy treatment, or a longer post-operative stay.137

Radiation therapy, in which the patient is alone in the treatment room receiving instructions from an outside voice, can be distressing for patients with severe anxiety, paranoia, or auditory hallucinations. A pre-treatment visit to the radiation therapy suite with explanations of the equipment and procedure may reduce patients’ anxiety, or help the patient and care team decide that radiotherapy is not appropriate.44

Interpersonal/Provider level

Consciously avoid the tendency towards “diagnostic over shadowing,” or attributing physical symptoms that may indicate cancer to the patient’s mental illness. Potential organizational level solutions to avoid diagnostic overshadowing include having peer navigators help in the coordination of care, better integration of care between mental health and health providers, and health care manager programs.141,153

Improve information sharing strategies between medical and mental health providers via shared electronic health records, health information exchanges, or personal health records

Assess decisional capacity on an individual basis, and tailor communication based on cognitive deficits or other psychiatric symptoms.145,44

Be aware of the many drug-drug interactions between psychiatric medications and chemotherapeutic drugs. For example, clomipramine, diphenhydramine, duloxetine, haloperidol, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine inhibit chemotherapy metabolism of some chemotherapeutic agents, while carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and St. John’s Wort increase chemotherapy metabolism.44,42

Clozapine use with cytotoxic chemotherapy is associated with increased risk of agranulocytosis, necessitating leukocyte count monitoring every one to two weeks.44,137

Antiemetic drugs that are dopamine agonists may result in acute movement disorders in patients taking antipsychotics; alternative antemetics to consider include cyclizine and 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptor (5-HT3) antagonists.44

Community/organizational level

Involve staff from community-based social supports, who often have long-term relationships with patients, early in the diagnostic and treatment process.

Address barriers to care such as housing and transportation, by providing free transportation to healthcare facilities such as clinics and increasing referrals to social services for housing placements.137

Health system level

Although people with SMI are often excluded from intervention studies, an SMI diagnosis should not prevent clinicians from offering patients with decisional capacity entry into clinical trials when appropriate.137

People with SMI are interested and able to engage in discussions of end-of-life treatment preferences based on hypothetical scenarios.152,156 Therefore, there should be more focus on eliciting and applying those preferences in actual clinical practice, including through the use of advance directives.

Conclusion

Given that cancer disparities in people with mental illness may in large part result from differential access to the opportunities and social conditions that maximize health outcomes, addressing these disparities can be viewed as an issue of social justice. This article serves to document these disparities and make recommendations for improvement based on available evidence and extensive clinical and public health experience. While multiple interventions are being developed and tested to address tobacco dependence and obesity in these populations, the evidence for effectiveness is quite limited, and essentially all prevention interventions focus at the individual level. This review was able to find only one published article describing a randomized controlled trial to promote cancer screening and improve cancer treatment in people with mental illness.140 We hope this article draws attention to the limitations of the medical model and the current the healthcare system to improve cancer control in this marginalized population.

As the ecological model reflects, there are multiple causal pathways that have led to cancer disparities in people with mental illness. While clearly there are health behavior issues, “if we accept that it is unjust to hold people accountable for things over which they have little control, then they should be held responsible for engaging in healthy behaviors only when they have full access to the conditions that enable those behaviors.”43,p61 Individual healthcare providers have significant opportunities to advocate for equal treatment of their patients with psychiatric disabilities. Similarly, individual healthcare settings, such as primary care clinics, emergency departments, and mammography centers, can provide ongoing staff education to reduce stigma and improve the patient experience for this group. It is critical to think of physical health as an integral and reimbursable element of psychiatric care necessitating health screening, preventive and treatment efforts as part of treatment planning for psychiatric conditions, particularly early in the treatment of mental disorders (first episode psychosis and when initiating someone with a psychiatric medication).

There are several large health policy measures that could improve cancer prevention and control in these individuals. This includes fully integrated medical and behavioral healthcare, particularly for people with serious mental illness,159 integrating preventive and treatment interventions in settings that commonly provide services to people with SMI (such as supportive housing) to bring health interventions to people doorsteps to reduce access and engagement barriers, and enhanced payment structures for organizations willing to take on care coordination for people with multiple, complex medical and psychiatric co-morbidities. Finally, advocating for anti-poverty measures, such as affordable housing, healthy food assistance programs, and programs that facilitate opportunities for mainstream community employment for people with disabilities, is what is ultimately needed to create the conditions that enable all people, especially those at highest risk, to be healthy. In the broadest sense, health is integral for mental health and vice-versa. There is “no health without mental health” and no mental health without health.160,161

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services-National Institutes of Health-National Institute of Mental Health

R01MH104574

American Cancer Society

123369-CCCDA-12-213-01-CCCDA

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states [serial online] Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parks J, Svendsen D, Singer P, Foti ME, Mauer B. Morbidity and Mortality in People With Serious Mental Illness. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2006. [Accessed July 31, 2015]. Technical Report 13. nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Mortality%20and%20Morbidity%20Final%20Report%208.18.08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) [Accessed July 18, 2015];Results From the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. NSDUH Series H-47, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4805. 2013 archive.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k12MH_FindingsandDetTables/2K12MHF/NSDUHmhfr2012.htm#sec2-1.

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Final notice establishing definitions for: 1) children with a serious emotional disturbance and 2) adults with a serious mental illness. Fed Regist. 1993;58:29422–29425. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen EM, McGinty EE, Azrin ST, Juliano-Bult D, Daumit GL. Review of the evidence: prevalence of medical conditions in the united states population with serious mental illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37:199–222. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Druss BG, Bornemann TH. Improving health and health care for persons with serious mental illness: the window for US federal policy change. JAMA. 2010;303:1972–1973. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran E, Rouillon F, Loze JY, et al. Cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia: an 11-year prospective cohort study. Cancer. 2009;115:3555–3562. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muirhead L. Cancer risk factors among adults with serious mental illness. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:S98–S103. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenleaf AT, Williams JM. Supporting social justice advocacy: a paradigm shift towards an ecological perspective. J Soc Action Couns Psychol. 2009;2:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabassa LJ, Siantz E, Nicasio A, Guarnaccia P, Lewis-Fernández R. Contextual factors in the health of people with serious mental illness. Qual Health Res. 2010;24:1126–1137. doi: 10.1177/1049732314541681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barak Y, Achiron A, Mandel M, Mirecki I, Aizenberg D. Reduced cancer incidence among patients with schizophrenia. Cancer. 2005;104:2817–2821. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barak Y, Levy T, Achiron A, Aizenberg D. Breast cancer in women suffering from serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(1–3):249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bushe CJ, Bradley AJ, Wildgust HJ, Hodgson RE. Schizophrenia and breast cancer incidence: a systematic review of clinical studies. Schizophr Res. 2009;114(1–3):6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catts VS, Catts SV, O’Toole BI, Frost AD. Cancer incidence in patients with schizophrenia and their first-degree relatives—a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117:323–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Lin H. Increased risk of cancer subsequent to severe depression—a nationwide population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2011;131(1–3):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgson R, Wildgust HJ, Bushe CJ. Cancer and schizophrenia: is there a paradox? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4 suppl):51–60. doi: 10.1177/1359786810385489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji J, Sundquist K, Ning Y, Kendler KS, Sundquist J, Chen X. Incidence of cancer in patients with schizophrenia and their first-degree relatives: a population-based study in Sweden. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:527–536. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, et al. General-medical conditions in older patients with serious mental illness. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:250–254. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levav I, Kohn R, Barchana M, et al. The risk for cancer among patients with schizoaffective disorders. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1–3):316–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin GM, Chen YJ, Kuo DJ, et al. Cancer incidence in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan, 1997–2009. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:407–416. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGinty EE, Zhang Y, Guallar E, et al. Cancer incidence in a sample of Maryland residents with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:714–717. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pandiani JA, Boyd MM, Banks SM, Johnson AT. Elevated cancer incidence among adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1032–1034. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabares-Seisdedos R, Dumont N, Baudot A, et al. No paradox, no progress: inverse cancer comorbidity in people with other complex diseases. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:604–608. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torrey EF. Prostate cancer and schizophrenia. Urology. 2006;68:1280–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.08.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldacre MJ, Kurina LM, Wotton CJ, Yeates D, Seagroat V. Schizophrenia and cancer: an epidemiological study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:334–338. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hippisley-Cox J, Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Parker C. Risk of malignancy in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: nested case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1368–1376. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barchana M, Levav I, Lipshitz I, et al. Enhanced cancer risk among patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grinshpoon A, Barchana M, Ponizovsky A, et al. Cancer in schizophrenia: is the risk higher or lower? Schizophr Res. 2005;73(2–3):333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitley E, Batty GD, Mulheran PA, et al. Psychiatric disorder as a risk factor for cancer: different analytic strategies produce different findings. Epidemiology. 2012;23:543–550. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182547094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bushe CJ, Hodgson R. Schizophrenia and cancer: in 2010 do we understand the connection? Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:761–767. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daumit GL, Anthony CB, Ford DE, et al. Pattern of mortality in a sample of Maryland residents with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176(2–3):242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piatt EE, Munetz MR, Ritter C. An examination of premature mortality among decedents with serious mental illness and those in the general population. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:663–668. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrence D, D’Arcy C, Holman J, Jablensky A, Threfall T, Fuller S. Excess cancer mortality in western Australian psychiatric patients due to higher case fatality rates. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:382–388. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101005382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kisely S, Sadek J, MacKenzie A, Lawrence D, Campbell LA. Excess cancer mortality in psychiatric patients. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:753–761. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:324–333. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kisely S, Forsyth S, Lawrence D. Why do psychiatric patients have higher cancer mortality rates when cancer incidence is the same or lower [published online ahead of print March 31, 2015]? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1177/0004867415577979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Design and Nature. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen DA, Scribner RA, Farley TA. A structural model of health behavior: a pragmatic approach to explain and influence health behaviors at the population level. Prev Med. 2000;30:146–154. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adler NE, Stewart J. Reducing obesity: motivating action while not blaming the victim. Milbank Q. 2009;87:49–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Damjanovic A, Ivkovic M, Jasovic-Gasic M, Paunovic V. Comorbidity of schizophrenia and cancer: clinical recommendations for treatment. Psychiatr Danub. 2006;18(1–2):55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howard LM, Barley EA, Davies E, et al. Cancer diagnosis in people with severe mental illness: practical and ethical issues. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:797–804. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinstein LC, Lanoue MD, Plumb JD, King H, Stein B, Tsemberis S. A primary care-public health partnership addressing homelessness, serious mental illness, and health disparities. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:279–287. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2013.03.120239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayer DK, Birken SA, Check DK, Chen RC. Summing it up: an integrative review of studies of cancer survivorship care plans (2006–2013) Cancer. 2015;121:978–996. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) [Accessed September 29, 2015];Wellness Initiative. samsha.gov/wellness-initiative.

- 49.van der Meer RM, Willemsen MC, Smit F, Cuijpers P. Smoking cessation interventions for smokers with current or past depression [serial online] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD006102. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006102.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibbons RD, Mann JJ. Varenicline, smoking cessation, and neuropsychiatric adverse events. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1460–1467. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartels SJ, Pratt SI, Aschbrenner KA, et al. Pragmatic replication trial of health promotion coaching for obesity in serious mental illness and maintenance of outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:344–352. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Daumit GL, Dickerson FB, Wang N, et al. A behavioral weight-loss intervention in persons with serious mental illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasnain M, Fredrickson SK, Vieweg WV. Metformin for obesity and glucose dysregulation in patients with schizophrenia receiving antipsychotic drugs. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:715–721. doi: 10.1177/0269881110389214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mitchell AJ, Pereira IE, Yadegarfar M, Pepereke S, Mugadza V, Stubbs B. Breast cancer screening in women with mental illness: comparative meta-analysis of mammography uptake. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:428–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aggarwal A, Pandurangi A, Smith W. Disparities in breast and cervical cancer screening in women with mental illness: a systematic literature review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Happell B, Davies C, Scott D. Health behaviour interventions to improve physical health in individuals diagnosed with a mental illness: a systematic review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2012;21:236–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, Rask KJ, Zhao L, Parker RM. The Primary Care Access Referral, and Evaluation (PCARE) study: a randomized trial of medical care management for community mental health settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:151–159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weitlauf JC, Jones S, Xu X, et al. Receipt of cervical cancer screening in female veterans: impact of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression [serial online] Womens Health Issues. 2013;23:e153–e159. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abrams MT, Myers CS, Feldman SM, et al. Cervical cancer screening and acute care visits among Medicaid enrollees with mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:815–822. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barley E, Borschmann RD, Walters P, Tylee A. Interventions to encourage uptake of cancer screening for people with severe mental illness [serial online] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD009641. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009641.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Irwin KE, Henderson DC, Knight HP, Pirl WF. Cancer care for individuals with schizophrenia. Cancer. 2014;120:323–334. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:616–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13050650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharma A, Ngan S, Nandoskar A, et al. Schizophrenia does not adversely affect the treatment of women with breast cancer: a cohort study. Breast. 2010;19:410–412. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Lin YL, Raji MA, Singh A, Goodwin JS. Effect of mental disorders on diagnosis, treatment, and survival of older adults with colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1268–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bergamo C, Sigel K, Mhango G, Kale M, Wisnivesky JP. Inequalities in lung cancer care of elderly patients with schizophrenia: an observational cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2014;76:215–220. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Foti ME, Bartels SJ, Van Citters AD, Merriman MP, Fletcher KE. End-of-life treatment preferences of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:585–591. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chengappa KN, Perkins KA, Brar JS, et al. Varenicline for smoking cessation in bipolar disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:765–772. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, et al. Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:145–154. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ahmed AI, Ali AN, Kramers C, Harmark LV, Burger DM, Verhoeven WM. Neuropsychiatric adverse events of varenicline: a systematic review of published reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:55–62. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31827c0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baker A, Richmond R, Haile M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a smoking cessation intervention among people with a psychotic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1934–1942. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brunette MF, Ferron JC, Devitt T, et al. Do smoking cessation websites meet the needs of smokers with severe mental illnesses? Health Educ Res. 2012;27:183–190. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cantrell M, Argo T, Haak L, Janney L. Adverse neuropsychiatric events associated with varenicline use in veterans: a case series. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33:665–669. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2012.692463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Evins AE. Reassessing the safety of varenicline. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1385–1387. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13091257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [Accessed July 31, 2015];FDA Drug Safety Communication: Safety review update of Chantix (varenicline) and risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events. fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm276737.htm.

- 75.US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [Accessed July 31, 2015];FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA updates label for stop smoking drug Chantix (varenicline) to include potential alcohol interaction, rare risk of seizures, and studies of side effects on mood, behavior, or thinking. fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm436494.htm.

- 76.Lavigne JE. Smoking cessation agents and suicide [serial online] BMJ. 2009;339:b4360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]