Abstract

In laboratory settings, the adult offspring of rodent dams that are maintained on high-fat diet (HFD) before conception and/or during pregnancy/lactation display an increased incidence of obese phenotypic markers, including increased body weight and adiposity, reduced leptin sensitivity, and impaired glucose tolerance. In rat pups raised by dams consuming HFD, these obese markers emerge during the first postnatal week. Since the week-old offspring of HFD dams consume excess amounts of milk during experimental tests of independent feeding (i.e., intake away from the dam), we hypothesized that maternal diet affects suckling and/or independent ingestion by pups in the home-cage environment. In the present study, this hypothesis was tested by conducting detailed analyses of ingestive behaviors expressed by pups in the home cage. Pups raised by dams consuming HFD displayed an earlier onset of independent feeding and more amounts of calorie intake from solid food during the third postnatal week compared to pups raised by dams consuming regular chow, with no diet-related differences in suckling behavior. Independent ingestion by pups in both diet groups was most frequently observed after nursing, with offspring of HFD dams engaged more frequently in post-nursing independent feeding episodes compared to offspring of chow-fed dams, particularly when the prior nursing episode was nutritive (i.e., including milk receipt by pups). We conclude that early-life exposure to HFD enhances the facilitative effect of nutritive suckling on independent feeding in pups, promoting increased caloric intake from solid food in the home-cage environment.

Keywords: High-fat diet, Obesity, Suckling, Independent feeding, Offspring, Nursing

1. INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a health condition in which chronic, excessive energy intake increases the risk of various health problems such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and depression, while reducing life quality and negatively impacting healthcare resources [1–3]. The prevalence of obesity is increasing markedly in both Western and developing countries, and is recognized worldwide as a major health problem [4, 5]. Based on recent data collected within the United States, approximately 70% of adults and 32% of children and adolescents are either overweight or obese [6]. Results from human and animal studies support the view that adult obesity is linked to interactions between genetic background and early life exposure to dietary and other environmental factors [3, 7–10].

Despite mounting evidence that early-life malnutrition predisposes offspring to adult obesity, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Metabolic programming is one potential explanation that derives from the “thrifty phenotype” or Barker hypothesis, positing that persistent shifts in physiology and metabolism can occur as the result of nutritional status during a sensitive period of early development [11–13]. In the suckling offspring of altricial mammalian species such as humans and rodents (e.g., rats and mice), maternal nutrition directly impacts the nutritional environment of the offspring in utero during prenatal development, through maternal milk consumed postnatally, and through foods made available to the developing offspring before and after weaning. Results from animal studies indicate that the offspring of female rodents maintained on high-fat diet (HFD) before conception and/or during pregnancy/lactation display an increased incidence of obese phenotypes, including elevated body weight (BW), hyperglycemia, hyperleptinemia, and leptin resistance [14–17]. The obese phenotype emerges prior to weaning and is maintained into adulthood even when offspring are weaned onto standard low-fat chow [9, 10, 18]. Thus, the effects of maternal HFD on offspring obese phenotypes include events that occur both pre- and postnatally [9, 10, 16], and presumably are linked to increased energy intake and/or reduced energy expenditure in the offspring [3].

Rat pups display two types of ingestive behavior: suckling and independent feeding. In the home-cage laboratory environment, rat pups suckle maternal milk through the end of the third postnatal week, and even longer if they are not separated from their dams [19, 20]. Independent feeding by pups (i.e., intake away from the dam) typically emerges during the third postnatal week [20–22], but can be elicited soon after birth under the proper experimental conditions [23]. Compared to the offspring of chow-maintained dams, the week-old (but not 3-day or 10-day old) offspring of HFD-fed dams reportedly consume more milk during experimental tests of independent feeding, even after correcting for their higher body weight [9]. This finding suggests that maternal HFD promotes some degree of hyperphagia in week-old offspring, as in adult rats [24, 25]. In another study that used specialized cages to separately feed dams and pups either chow or HFD, pups reared by dams on HFD and/or with their own access to HFD displayed an earlier onset of independent feeding [26]. However, no reports exist regarding the effects of maternal HFD on the incidence and interaction of suckling and independent feeding behaviors displayed by pre-weanling rat pups in the home-cage environment. Nutritive suckling in rats depends on the dam’s nursing posture and the pup’s nipple-attaching and active suckling behaviors for milk transfer, and independent feeding in the home-cage environment is strongly influenced by the presence of the dam and littermates [27–29]. To test the hypothesis that maternal diet during gestation and lactation has a significant impact on the offspring’s early ingestive behaviors, the present study conducted a detailed behavioral analysis of suckling and independent feeding behaviors exhibited by pre-weanling offspring of HFD- and chow-maintained dams in the home-cage environment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal care and experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.1. Animals

Three experimental cohorts of timed-pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (3–4 pregnant rats per cohort; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA) were used. Upon arrival at the animal facility on gestation day (G) 2 or 3, pregnant females were weighed and assigned to either standard chow [CHOW: LabDiet #5001 (13.5% kcal from fat), Purina, Bethlehem, PA, USA; n=5] or HFD [D12492 (60% kcal from fat), Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA; n=6]. Pregnant females were housed individually in clear polyethylene cages with soft woodchip bedding within a temperature-controlled room (20–22°C) under a 12/12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h). Cage lids also were clear polyethylene, to facilitate video recording of behavior (see 2.2, below). Rats had continuous ad libitum access to water obtained from a bottle and their assigned diet obtained from a wire feeder attached to a sidewall of the cage.

Cages were checked for pups each day at the end of light cycle, and the day of parturition was designated postnatal day (P)0. On the following morning (P1), litter sizes were reduced to either 10 (cohort 1) or 8 pups (cohorts 2 and 3), balanced for sex. In one HFD litter that was sex-unbalanced, pups were cross-fostered from another HFD litter born on the same day to achieve sex-balance in both litters. Pups were removed briefly from their dam on P1, P7, P14, and P21 (the day of weaning) in order to assess body weights (BW). Cumulative HFD or chow intake by the dam and pups (collectively within the home cage) was assessed daily from P1–P21.

2.2. Behavioral observations

Behavioral data were collected in litters from the second and third experimental cohorts (CHOW: n=3 dams, HFD: n=4 dams; 8 pups per litter). Using two cameras per cage (FI8910W, Foscam Digital Technologies, Houston, TX, USA), video records were obtained daily from P0–P20 for 3 h via continuous observation during the middle of each light cycle (1130–1430 h) and for 3 h during the middle of each dark cycle (2330–0230 h) under red light invisible to albino rats, and stored on computers for behavioral scoring later. For each cage, one camera recorded a “birds-eye view” of the dam and pups through the clear polyethylene cage lid, and the second camera simultaneously captured a front view. A mirror placed behind each cage provided a view of animals that were otherwise hidden from the front-view camera. Time stamps were simultaneously created by commercial video surveillance software (SecuritySpy, Bensoftware, London, UK) and used to temporally document the initiation and termination of assessed behaviors according to the operational definitions described below.

2.2.1. Suckling

In order to examine the effect of maternal diet on suckling behavior by the offspring, pups’ stretching response to milk letdown/receipt was monitored. When milk letdown occurs, pups attached to the nipples cease other activities for several seconds and simultaneously display dorsiflexion of the back with the limbs firmly extended [30, 31]. This well-documented synchronous “stretch response” has been used as an effective index of milk receipt in previous reports [32–34]. Stretching responses in the present study were quantified only during the second and third postnatal weeks (P7–P20), since the small body size of younger pups (which often were obscured by the dam) interfered with consistent and reliable video recording and scoring.

2.2.2. Independent feeding

Independent feeding by pups was monitored from P14–P20 and emerged in all litters during the third postnatal week, consistent with previous reports [20–22]. Independent feeding was scored when the feeder was directly accessed by one or more pups during the observation period. Since up to three pups could simultaneously access the feeder, it was not practical to attempt to track pups’ individual independent feeding behavior. Independent feeding was considered to have occurred when the snout of one or more pup(s) contacted the feeder, and the pup(s) displayed simultaneous chewing-like jaw movement for at least 3 sec. This operational definition was created to exclude brief instances of feeder contact during home-cage exploration. The same operational definition was used to quantify the dam’s feeding behavior.

2.2.3. Nursing

Dam’s nursing was monitored to examine a possible association between nursing/suckling and pup independent feeding during the third postnatal week (P15–P20), based on our preliminary observation that pups often initiated independent feeding soon after the dam left her litter at the termination of nursing (see Results). Dams need stimulation from the pups through nipple attachment, perioral contact, and odor in order to assume nursing postures and eject milk [35, 36]. The strength of this sensory stimulation depends on the number of pups, and a threshold number of nipple-attached pups is necessary to evoke milk letdown [35, 36]. Until setting down with one nipple during a suckling bout, pups often repeatedly switch nipples by attaching and disengaging. In the present study, we noted that pups’ stretching responses (indicative of milk letdown/receipt, as detailed in 2.2.1, above) primarily occurred when four or more pups were attached, and that transient periods of nipple attachment (i.e., less than a minute) including the one during nipple switching before setting down with one nipple did not precede stretching responses even when more than half the pups were engaged in nipple switching. For these reasons, the initiation of a maternal nursing bout in the present study was defined as the point at which at least four pups were engaged in nipple attachment that was maintained for at least 1.5 min, as this operational definition of nursing addressed both the number of pups engaging in nipple attachment and the duration of attachment. Nipple attachment could often be directly observed, but was inferred when a pup’s mouth was obscured by the dam’s body. The termination of nursing was defined as a subsequent point during the observation period when at least six pups detached from the nipple.

The frequency and duration of nursing bouts were recorded during each 3-hr observational session from P15–P20. Bout duration was scored only for nursing episodes in which both bout initiation and termination were recorded. Nursing episodes also were coded as to whether or not they were followed by pup independent feeding within 40 min after nursing bout termination (as detailed in 2.2.4, below). The inter-nursing bout interval (i.e., between two recorded nursing episodes) also was quantified and analyzed with respect to total bout incidence, duration, and frequency.

2.2.4. Categorization of independent feeding in relation to nursing

A mentioned above, preliminary observations indicated that pups often initiated independent feeding soon after the termination of nursing. Thus, we sought to identify a potential temporal association of pups’ independent feeding with interwoven nursing bouts. For this purpose, independent feeding was sorted into four categories (see Figure 1): (i) Feeding after nursing: feeding observed within 40 min after the termination of a nursing bout; (ii) Feeding during nursing: feeding observed by some pups while the dam continued to nurse other pups; (iii) Feeding out of nursing: feeding observed later than 40 min after termination of the last nursing bout, and in the absence of simultaneous nursing by other pups; and (iv) Feeding after unidentified nursing: feeding observed at the beginning of a 3-hr observation period, and therefore, not temporally linked to the previous (unrecorded) nursing bout. We defined 40 min as the selected time range for independent feeding “after nursing” based on the observed duration of inter-nursing bout intervals (see Results). Feeding after nursing was further categorized as to whether or not the most recent nursing bout terminated prior to independent feeding elicited a stretching response by pups to milk letdown/receipt, thereby distinguishing a nutritive as opposed to a non-nutritive suckling bout.

Figure 1.

Operational definitions for four categories of independent feeding in relation to nursing. (i) Feeding after nursing: feeding episode observed within 40 min after the termination of nursing. (ii) Feeding during nursing: feeding episode observed while the dam nursed other pups. (iii) Feeding out of nursing: feeding episode observed more than 40 min after termination of the prior nursing bout, with no simultaneous nursing of other pups. (iv) Feeding after unidentified nursing: feeding episode ongoing at the beginning of the observation period, with the prior nursing bout terminating at an unknown time.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the effect of maternal diet (HFD vs. CHOW) on pup BW during the postnatal period. To assess the effect of maternal diet on a given postnatal day, a post hoc ANOVA with Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used. The overall effect of diet on male and female pup’s BW was examined using the litter mean for each sex (n = 5 CHOW and 6 HFD litters), and data from individual animals were used to examine the diet effect on BW at a given postnatal day (n = 22/sex in CHOW and 25/sex in HFD groups). Mixed-model ANOVA with maternal diet as the between-subject measure was used to identify significant differences among the four categories of independent feeding in relation to nursing, which was followed by post hoc tests using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, as well as to examine the effect of milk receipt on pups’ independent feeding after nursing, and to compare independent feeding before and after nursing. In mixed-model ANOVAs, a Greenhouse-Geisser correction for sphericity was applied, if necessary. The effect of maternal diet on pup independent feeding over a specific period of postnatal life, or during the 40 min period after nursing, was examined using a t-test to compare areas under the curve (AUC), with diet effect on a given postnatal day or time-point assessed using a t-test. For all other comparisons, data were analyzed using t-tests to compare results in HFD vs. CHOW groups, unless otherwise specified (see Results). Analyses of behavioral measures (suckling, independent feeding, and nursing) were conducted using data collected from continuous observations on 7 litters (n = 3 CHOW and 4 HFD litters). Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM corporation, Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented in tables and graphs as group mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effect of maternal diet on maternal BW and nursing parameters

Upon arrival at our animal facility on G2-3, dams assigned to each diet group (i.e., CHOW or HFD) had similar BWs, and there was no subsequent effect of diet on maternal BWs assessed at G19, P1 or P21 (Table 1). During the third postnatal week when pups displayed feeding emerged (i.e., P15–P20, see Results), maternal nursing bout frequency and duration of nursing were similar between HFD and CHOW dams, as were the number and durations of breaks between nursing bouts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dams’ body weight during gestation and lactation and nursing parameters during the third postnatal week (P15–P20). Maternal diet did not affect either body weight or nursing parameters in dams. G: Gestation day. P: Postpartum day.

| CHOW dams | HFD dams | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | ||

| G2-3 | 249.8 ± 15.8 | 262.3 ± 16.2 |

| G19 | 371.0 ± 21.7 | 378.2 ± 21.0 |

| P1 | 291.6 ± 18.9 | 306.3 ± 18.8 |

| P21 | 319.8 ± 12.7 | 320.5 ± 17.4 |

| Nursing Parameters | ||

| Number of nursing bouts | 31.0 ± 2.6 | 27.5 ± 3.6 |

| Avg. bout duration (min) | 30.9 ± 1.5 | 26.9 ± 1.3 |

| Total bout duration (min) | 763.4 ± 98.0 | 641.9 ± 76.2 |

| Number of nursing breaks | 28.7 ± 1.9 | 26.3 ± 3.4 |

| Avg. break duration (min) | 30.5 ± 3.3 | 38.6 ± 3.6 |

| Total break duration (min) | 801.4 ± 80.1 | 884.0 ± 53.2 |

3.2. Effect of maternal diet on pup BW

There was a significant main effect of maternal diet on the BW of both male (F(1,9) = 69.8, p < 0.001) and female offspring (F(1,9) = 61.1, p < 0.001), such that HFD pups were heavier than CHOW pups over the postnatal period (Figure 2). Analysis of diet effect at a given postnatal day showed that on P1, CHOW males (7.8 ± 0.1g) were slightly but significantly heavier than HFD males (7.5 ± 0.1g, F(1,45) = 4.7, p = 0.036), whereas female CHOW and HFD pups had similar BWs (7.2 ± 0.1 g and 7.2 ± 0.1 g, respectively). By P7, however, both male and female HFD pups weighed more than CHOW pups (HFD vs. CHOW males, F(1, 45) = 21.7, p < 0.001; HFD vs. CHOW females, F(1, 45) = 17.1, p < 0.001). As evident in Figure 2, the significant effect of diet on pup BW was maintained at P14 (HFD vs. CHOW males F(1, 45) = 199.1, p < 0.001; HFD vs. CHOW females F(1, 45) = 175.8, p < 0.001) and P21 (HFD vs. CHOW males F(1, 45) = 317.1, p < 0.001; HFD vs. CHOW females F(1, 45) = 253.8, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Body weight in male (A) and female (B) offspring of HFD- vs. CHOW-fed dams. HFD pups of both sexes were heavier than CHOW pups at P7, P14, and P21 (*p < 0.05). On P1, male CHOW pups weighed slightly but significantly more than male HFD pups (#p < 0.05).

3.3. Home-cage caloric intake of solid food (dams plus pups)

Maternal total caloric intake was comparable in HFD and CHOW dams before parturition (1260.7 ± 56.4 kcal and 1257.3 ± 40.5 kcal, respectively). The cumulative home-cage caloric intake from P1 to P21 also was similar between HFD and CHOW groups (Figure 3A). When each postnatal week was considered separately, however, home-cage caloric intake in HFD cages exceeded that in CHOW cages during the third postnatal week (i.e., P15–P21) (Figure 3B: t(9) = −3.13, p = 0.012). It is important to note that this caloric intake measure reflects the amount consumed by both the dam and offspring, and the latter began to consume HFD or CHOW during the third postnatal week (see 3.4, below). Assessment of the total time that dams spent engaged in feeding using paired t-test revealed that the amount of time that HFD dams spent engaged in feeding did not differ between the second and third postnatal weeks (Figure 3C), suggesting that increased HFD intake by offspring accounted for increased total home-cage caloric intake during the third postnatal week (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Home-cage caloric intake from solid food, and dam’s feeding time postpartum. (A) Cumulative caloric intake (dams plus pups) was similar in CHOW and HFD groups. (B) During the third postnatal week, rats in HFD groups consumed more total calories from solid food compared to CHOW groups (*p < 0.05). (C) HFD dams spent similar total amounts of time engaged in feeding during the second and third postnatal weeks.

3.4. Assessment of ingestive behaviors by HFD vs. CHOW pups

The cumulative frequency of pups’ stretching responses to milk receipt (i.e., a measure of nutritive suckling) was comparable between HFD and CHOW litters (Figure 4A), consistent with the lack of difference between CHOW and HFD dams in assessed nursing parameters (Table 1). When each postnatal week was considered separately, there also were no differences between the two maternal diet groups in pups’ nutritive suckling frequency.

Figure 4.

Suckling and independent feeding by pups. (A) The total number of stretching responses (indicative of milk receipt) was similar in CHOW and HFD pups from P7–P20. (B) During the third postnatal week, the total amount of time spent engaged in independent feeding was higher in HFD vs. CHOW pups as indicated by AUC (inset), although this difference did not reach significance. HFD pups cumulatively spent more time engaged in independent feeding on P17 and P18 compared to CHOW pups (*p < 0.05).

The first observed incidence of independent feeding by pups in both HFD and CHOW group occurred on P15, and there was no group difference in latency to the first independent feeding (15.0 ± 0.0 and 15.8 ± 0.3 days in CHOW and HFD groups, respectively). Nevertheless, the subsequent progressive increase in independent feeding differed between the two diet groups (Figure 4B). This difference was apparent by P16 and became significant by P17, when pups in HFD litters spent significantly more cumulative time engaged in independent feeding during observational sessions (Figure 4B: P17-dark cycle: t(5) = −3.29, p = 0.022, P18-light: t(5) = −3.08, p = 0.027, and P18-dark: t(5) = −2.81, p = 0.037). Nevertheless, the total time of independent feeding was comparable in HFD pups and CHOW pups based on AUC (Figure 4B), though HFD pups showed a trend to a longer total time spent for independent feeding.

3.5. Temporal association of independent feeding bouts and nursing

3.5.1. Post-nursing independent feeding as pup ingestive behavior affected by maternal diet

As described in the Methods (2.2.4), independent feeding bouts were categorized as occurring after nursing, during nursing, out of nursing, or after unidentified nursing (Figure 1) from P15–P20. As shown in Figure 5, the total time that pups spent engaged in independent feeding was significantly different across these four categories (F(3, 15) = 29.63, p < 0.001), and there also was a significant interaction between independent feeding category and maternal diet (F(3, 15) = 6.05, p = 0.007). Pairwise comparisons revealed that HFD pups spent markedly more total time engaged in independent feeding after nursing (8708.6 ± 1234.7 sec) compared to out of nursing (406.8 ± 169.9 sec, p = 0.006), during nursing (362.0 ± 99.7 sec, p = 0.006), or after unidentified nursing (832.5 ± 356.4 sec, p = 0.012). There was no significant difference among independent feeding categories in CHOW pups, but with a trend towards significance (p = 0.060). Accordingly, HFD pups spent significantly more time engaged in independent feeding after nursing compared to CHOW pups (Figure 5; t(5) = −2.70, p = 0.043), with no diet-related differences in the other three categories of independent feeding (i.e., during nursing, out of nursing, or after unidentified nursing). Moreover, pups in HFD litters displayed a significantly higher proportion of total nursing episodes that were followed by independent feeding (i.e., feeding after nursing) compared to pups in CHOW litters (Figure 6; t(5) = −2.98, p = 0.041). Thus, HFD pups were significantly more likely to engage in independent feeding after nursing compared to CHOW pups.

Figure 5.

Independent feeding categorized in relation to nursing during the third postnatal week (see text and Figure 1 for operational definitions). HFD pups spent more time engaged in independent feeding after nursing compared to feeding in the other nursing-related categories (#p < 0.05), and also spent more time for feeding independently after nursing than CHOW pups (*p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

The proportion of observed nursing episodes followed by pup independent feeding during the third postnatal week. A higher proportion of nursing episodes was followed by pup independent feeding (within 40 min) in HFD vs. CHOW litters (*p < 0.05).

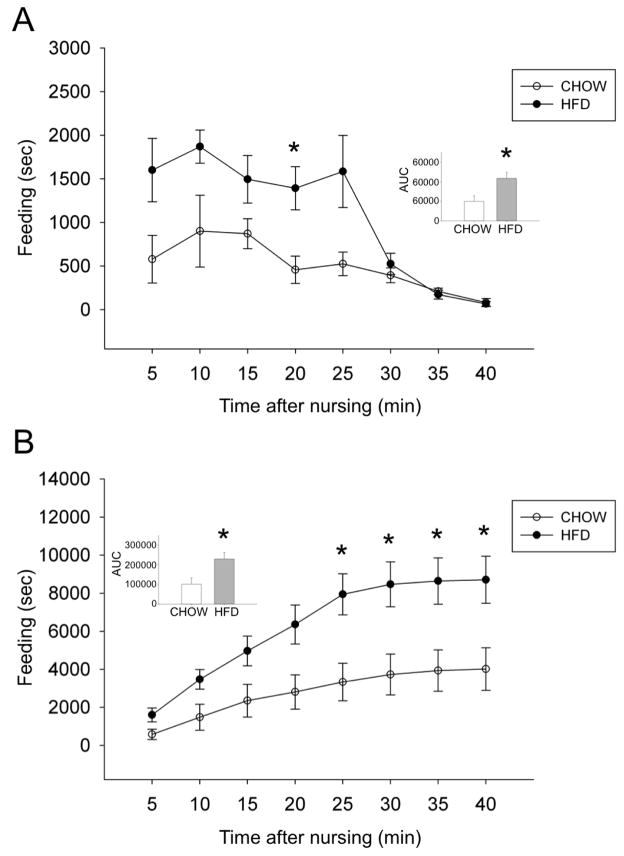

3.5.2. Assessment of independent feeding after nursing

Given that HFD pups spent more time engaged in independent feeding after nursing compared to CHOW pups from P15–P20 with no significant diet group-related differences in the other categories of independent feeding, the incidence of independent feeding after nursing was further analyzed within 5 min intervals over the 40 min period after the termination of each completely observed nursing bout (Figure 7A). In accordance with the effect of maternal diet on total time spent engaged in independent feeding after nursing (Figure 5), a significant main effect of maternal diet was identified based on AUC (t(5) = −2.73, p = 0.041; inset, Figure 7A). Compared to CHOW pups, HFD pups spent more time engaged in independent feeding for 25 min after nursing, although post-hoc t-tests revealed that the binned data were significantly different between diet groups at only the 20 min time point (Figure 7A: t(5) = −2.92, p = 0.033). Similarly, based on AUC, there was a significant main effect of maternal diet on the cumulative amount of time spent engaged in independent feeding after the termination of suckling (inset, Figure 7B; t(5) = −2.68, p = 0.044), which was significantly elevated in HFD pups from 25–40 min after suckling (25min: t(5) = −3.02, p = 0.029, 30min: t(5) = −2.86, p = 0.036, 35min: t(5) = −2.76, p = 0.040, 40min: t(5) = −2.70, p = 0.043).

Figure 7.

Pup independent feeding after nursing during the third postnatal week. (A) Total duration of pup independent feeding at each 5-min timepoint for 40 min after nursing. The AUC (inset) indicates that HFD pups spent more time engaged in independent feeding than CHOW pups (*p < 0.05), although the time-binned group difference was significant only at the 20 min time point. (B) Cumulative time spent engaged in independent feeding after nursing. HFD pups spent more time feeding independently than CHOW pups, with a significant group difference emerging 25 min after nursing (*p < 0.05 from 25–40 min).

3.5.3. Termination of nursing as a stimulus for independent feeding

Since the time range for categorizing “feeding after nursing” (40 min) was operationally defined based on the inter-nursing bout interval, independent feeding after nursing may have included independent feeding that was temporally associated with a subsequent nursing episode (i.e., “feeding before nursing”). To examine the association of independent feeding with timing of nursing (i.e., before vs. after nursing), independent feeding episodes that occurred within a 10-min period either before or after a fully-observed nursing episode were isolated. There was a significant main effect of timing on the total time pups spent engaged in independent feeding from P15–20 (F(1,5) = 12.74, p = 0.016), but no significant effect of maternal diet and no interaction between diet and timing. Accordingly, when data from HFD and CHOW pups were collapsed and re-analyzed to isolate the effect of timing using a paired t-test (Figure 8), significantly more independent feeding occurred after nursing than before nursing (t(6) = −3.97, p = 0.007), indicating that the termination of suckling facilitates independent feeding in pups, regardless of maternal diet.

Figure 8.

Cumulative time spent by pups in independent feeding during the third week postnatal, categorized as occurring either before or after a nursing bout. Pups (HFD and CHOW groups combined, because of no interaction with maternal diet) spent more time feeding independently within the 10-min period after nursing than before nursing (*p < 0.05).

3.6. Nutritive suckling as a factor for enhanced independent feeding in HFD pups

Given that the termination of suckling generally facilitated pup independent feeding, the association of independent feeding after nursing was further analyzed based on whether or not the prior nursing bout was “nutritive”, i.e., with pups’ stretching response documenting milk receipt. A significant main effect of milk receipt on subsequent independent feeding was evident (F(1,5) = 85.94, p < 0.001; Figure 9), suggesting that nutritive suckling facilitates independent feeding in pups, regardless of maternal diet. There also was a main effect of maternal diet on independent feeding after nursing (F(1,5) = 7.29, p = 0.043), and a significant interaction with milk receipt (F(1,5) = 11.12, p = 0.021), such that HFD pups displayed more independent feeding after nutritive nursing compared to CHOW pups (t(5) = −3.06, p = 0.028; Figure 9). In contrast, independent feeding after non-nutritive suckling was statistically similar in HFD and CHOW pups (653.0 ± 356.4 sec and 266.0 ± 240.7 sec, respectively; Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Independent feeding by pups after a nutritive vs. non-nutritive suckling episode (i.e., with or without stretching responses indicative of milk receipt). Regardless of maternal diet, the duration of independent feeding after nursing was greater when the nursing episode included milk receipt by pups (#p < 0.05 vs. duration without milk receipt). HFD pups displayed more independent feeding after milk receipt compared to CHOW pups (*p < 0.05), whereas there was no diet group difference in independent feeding after nursing that induced no milk receipt in pups.

4. DISCUSSION

Results from previous studies indicate that the offspring of female rats maintained on a HFD during pregnancy and lactation display an obese phenotype (i.e., increased BW, hyperleptinemia, reduced leptin sensitivity, and impaired glucose tolerance) that is apparent by the end of the first postnatal week and is maintained into adulthood [9, 10, 18]. As in the present report, developing offspring in those earlier studies were exposed to the effects of maternal diet in utero through the placenta, orally through suckling during the first two postnatal weeks, and orally through both suckling and independent feeding during the third postnatal week. Although one week-old rat pups born to dams maintained on HFD are reported to consume more milk in experimental tests of independent feeding [9], it has been unclear whether maternal HFD affects suckling and/or independent feeding by pre-weanling offspring in their home-cage environment. This is an important question, since pups’ ingestive behaviors are influenced by the behavior of the dam and littermates [27–29].

The present study provides the first evidence that maternal HFD increases independent feeding in pre-weanling offspring without affecting suckling behavior. In both CHOW and HFD pups, independent feeding bouts were facilitated by the termination of nursing, especially nutritive nursing with milk receipt, and HFD pups displayed comparatively more independent feeding than CHOW pups after nutritive suckling. Thus, early-life exposure to HFD appears to enhance the facilitative effect of nutritive nursing on independent feeding in pups. We propose that this facilitation contributes to increased caloric intake from solid food, and thereby to the greater BW gain of HFD pups during the pre-weaning period.

4.1. Maternal HFD increases pre-weanling offspring body weight

Mechanisms underlying the effect of maternal HFD on offspring development may differ depending on the timing of HFD exposure [37]. Previous reports indicate that maternal exposure to HFD during lactation promotes increased offspring BW/adiposity and obesity phenotypes to a greater extent compared to HFD exposure during gestation [10, 17], supporting the view that the metabolic phenotype of offspring are impacted more significantly by postnatal rather than prenatal factors [38]. There was no significant effect of diet on maternal BW during pregnancy or lactation in the present study, consistent with previous reports [9, 10, 15, 18, 39]. Nevertheless, HFD pups of both sexes were heavier than CHOW pups at P7 and later, as previously reported [9, 10, 18, 40]. Thus, maternal diet, rather than maternal obesity per se, appears to predispose pre-weanling offspring to obesity. Interestingly, newborn male HFD pups (P1) weighed slightly but significantly less than male CHOW pups, a difference that was absent in female offspring. Some studies have reported that maternal HFD reduces fetal and newborn BW [18, 41–43]. However, other studies report no such effect [9, 10, 40], perhaps due to different dietary fatty acid compositions with various levels of saturated fat across studies [41].

Independent feeding by HFD and CHOW pups in their home cage environment was first observed during the third postnatal week (i.e., on P15), consistent with previous reports [20–22]. Accordingly, the higher BW of HFD offspring during the first two weeks postnatal must arise from factors that increase pups’ energy intake during suckling and/or factors that reduce energy expenditure, whereas the higher BW of HFD offspring after P15 could also be due to increased energy intake through independent ingestion of solid food. Given that increased BW in HFD pups is maintained into adulthood even when pups are weaned to standard chow [9, 10, 18], early HFD intake by pre-weanling offspring might significantly impact their subsequent metabolic phenotype through a mechanism independent from the effects of maternal HFD.

4.2. Maternal HFD does not alter assessed suckling parameters

Although HFD offspring of both sexes weighed more than CHOW offspring on P7 and later as previously reported [9, 10, 18, 40], the incidence of milk receipt was comparable between the diet groups during the second and third postnatal weeks, as were nursing bout and nursing break parameters during the third week. An earlier report also found no effect of maternal diet on dams’ nursing postures during the second week postnatal [9]. Maternal diet might differentially affect milk receipt by pups during the first week postnatal, but this could not be reliably scored before P7 in the present study. Alternatively, or in addition, the higher BW of HFD pups on P7 (and later) could be due to reduced energy expenditure [44] and/or differences in maternal milk composition (e.g., fat or leptin levels) [9, 10, 17, 39, 44–46].

4.3. Maternal HFD facilitates early independent feeding

Pups in both diet groups first displayed independent feeding on P15, but HFD pups spent more cumulative time engaged in independent feeding from P15–P18. This new result is consistent with a previous study in which rat dams were maintained on a standard chow or fat-enriched diet before and after parturition, and then were moved together with their litters on P12 to customized three-chambered testing cages that permitted separate analysis of food intake by dams and pups [26]. In that study, weaning onset was operationally defined as the day on which a litter of pups collectively consumed at least 1 gram of a powdered form of the same fat-enriched or standard diet consumed by their dam; this occurred on the evening of P16 in fat-exposed pups, 24 hrs earlier than in chow-exposed pups [26]. The amount of solid food consumed by dams and pups was not analyzed separately in the present study. Nevertheless, HFD groups (dams + litters) consumed more calories from solid food than CHOW groups only after pups began to feed independently during the third postnatal week. Since there was no difference in the amount of time that HFD dams spent engaged in feeding during the second and third postnatal weeks, the higher incidence of independent feeding by HFD pups during the third week was likely responsible for the increased caloric intake by HFD rats. HFD feeding induces hyperphagia in adult rats [24, 25], and our results suggest that this also is true in pre-weanling as well as juvenile rats weaned onto standard chow [47] after early-life exposure to HFD.

4.4. Maternal HFD enhances pup independent feeding after nutritive nursing

The highest incidence of independent feeding by pups was observed after nutritive nursing, when HFD pups displayed more independent feeding than CHOW pups. Given that HFD pups displayed more nursing episodes that were followed by independent feeding compared to CHOW pups, HFD may enhance pup independent feeding through an effect related to nursing-induced behavioral stimulation, as reported previously [48]. Age-related changes in pups’ behavioral arousal and activities have been documented [20, 49], including arousal at the termination of a suckling bout [48, 50] that is induced by withdrawal of perioral stimulation, perhaps facilitating pups to leave the nest and encounter solid food [48]. Consequently, despite the locomotor ability to freely feed, three-week-old pups may rely on the post-suckling behavioral arousal to display independent feeding, and thereby independent feeding occurs mostly after nursing [48] as seen in the present study. Interestingly, although milk receipt is unnecessary for post-suckling behavioral arousal in rat pups [48], milk receipt additionally facilitated independent feeding in the present study, especially in HFD pups. This differential response in HFD pups might reflect impaired satiety signaling, as reported in adult HFD rats [51–53]. Thus, HFD exposure may augment the generally facilitative effect of nutritive suckling on independent feeding in pups, consequently increasing caloric intake prior to weaning.

4.5. Conclusion

The present study provides the first evidence that maternal HFD increases home-cage independent feeding in pre-weanling rat offspring, without affecting suckling behavior. Increased HFD intake by pups not only promotes increased total caloric intake during the third postnatal week, but also directly exposes the pup’s digestive system to higher levels of dietary fat. Continued work to distinguish the differential and combined effects of maternal HFD and offspring early-life independent HFD exposure may promote an improved understanding of the developmental origins of adult obese phenotypes.

Highlights.

Maternal HFD enhances pup independent feeding but not suckling behaviour.

Maternal HFD facilitates the onset of independent feeding in pups.

HFD increases caloric intake from solid food prior to weaning.

Nursing bouts often precede independent feeding by pups.

Maternal HFD enhances the facilitative effect of nursing on pup independent feeding.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant MH081817 (to L.R.) and the Summer Undergraduate Research Program in the Center for Neuroscience at the University of Pittsburgh (C.C.). The authors are grateful to Victoria Maldovan Dzmura for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BWJH, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:220–9. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor PD, Poston L. Developmental programming of obesity in mammals. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:287–98. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. 894. World Health Organization; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James PT, Leach R, Kalamara E, Shayeghi M. The worldwide obesity epidemic. Obes Res. 2001;9:228S–33S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:806–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biro FM, Wien M. Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1499S–505S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28701B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levin BE. Interaction of perinatal and pre-pubertal factors with genetic predisposition in the development of neural pathways involved in the regulation of energy homeostasis. Brain Res. 2010;1350:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purcell RH, Sun B, Pass LL, Power ML, Moran TH, Tamashiro KLK. Maternal stress and high-fat diet effect on maternal behavior, milk composition, and pup ingestive behavior. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:474–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun B, Purcell RH, Terrillion CE, Yan J, Moran TH, Tamashiro KLK. Maternal high-fat diet during gestation or suckling differentially affects offspring leptin sensitivity and obesity. Diabetes. 2012;61:2833–41. doi: 10.2337/db11-0957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer JS, Rosenfeld CR. Metabolic imprinting by prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal overnutrition: a review. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:266–76. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hales CN, Barker DJP. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Br Med Bull. 2001;60:5–20. doi: 10.1093/bmb/60.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hales CN, Barker DJP. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: the thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Diabetologia. 1992;35:595–601. doi: 10.1007/BF00400248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilbo SD, Tsang V. Enduring consequences of maternal obesity for brain inflammation and behavior of offspring. FASEB J. 2010;24:2104–15. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo F, Jen KLC. High-fat feeding during pregnancy and lactation affects offspring metabolism in rats. Physiol Behav. 1995;57:681–6. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srinivasan M, Katewa SD, Palaniyappan A, Pandya JD, Patel MS. Maternal high-fat diet consumption results in fetal malprogramming predisposing to the onset of metabolic syndrome-like phenotype in adulthood. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;291:E792–E9. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00078.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vogt MC, Paeger L, Hess S, Steculorum SM, Awazawa M, Hampel B, et al. Neonatal insulin action impairs hypothalamic neurocircuit formation in response to maternal high-fat feeding. Cell. 2014;156:495–509. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rother E, Kuschewski R, Alcazar MAA, Oberthuer A, Bae-Gartz I, Vohlen C, et al. Hypothalamic JNK1 and IKKβ activation and impaired early postnatal glucose metabolism after maternal perinatal high-fat feeding. Endocrinology. 2012;153:770–81. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cramer CP, Thiels E, Alberts JR. Weaning in rats: I. Maternal behavior Dev Psychobiol. 1990;23:479–93. doi: 10.1002/dev.420230604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiels E, Alberts JR, Cramer CP. Weaning in rats: II. Pup behavior patterns. Dev Psychobiol. 1990;23:495–510. doi: 10.1002/dev.420230605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babický A, Parízek J, Ostádalová I, Kolár J. Initial solid food intake and growth of young rats in nests of different sizes. Physiol Bohemoslov. 1973;22:557–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redman RS, Sweney LR. Changes in diet and patterns of feeding activity of developing rats. The Journal of nutrition. 1976;106:615–26. doi: 10.1093/jn/106.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall WG. What we know and don’t know about the development of independent ingestion in rats. Appetite. 1985;6:333–56. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(85)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savastano DM, Covasa M. Adaptation to a high-fat diet leads to hyperphagia and diminished sensitivity to cholecystokinin in rats. J Nutr. 2005;135:1953–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.8.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warwick ZS, McGuire CM, Bowen KJ, Synowski SJ. Behavioral components of high-fat diet hyperphagia: meal size and postprandial satiety. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R196–R200. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.1.R196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doerflinger A, Swithers SE. Effects of diet and handling on initiation of independent ingestion in rats. Dev Psychobiol. 2004;45:72–82. doi: 10.1002/dev.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galef BG. Social effects in the weaning of domestic rat pups. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1971;75:358–62. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galef BG, Clark MM. Mother’s milk and adult presence: Two factors determining initial dietary selection by weanling rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1972;78:220–5. doi: 10.1037/h0032293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerrish CJ, Alberts JR. Differential influence of adult and juvenile conspecifics on feeding by weanling rats (Rattus norvegicus): A size-related explanation. J. Comp. Psychol. 1995;109:61–7. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.109.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drewett RF, Statham C, Wakerley JB. A quantitative analysis of the feeding behaviour of suckling rats. Anim Behav. 1974;22(Part 4):907–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(74)90014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lincoln DW, Hill A, Wakerley JB. The milk-ejection reflex of the rat: An intermittent function not abolished by surgical levels of anaesthesia. J Endocrinol. 1973;57:459–76. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0570459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lonstein JS, Stern JM. Role of the midbrain periaqueductal gray in maternal nurturance and aggression: c-fos and electrolytic lesion studies in lactating rats. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3364–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03364.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedersen CA, Boccia ML. Oxytocin antagonism alters rat dams’ oral grooming and upright posturing over pups. Physiol Behav. 2003;80:233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smotherman WP, Robinson SR. Fetal heart rate response to milk predicts expression of the stretch response. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:833–7. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90123-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stern JM. Somatosensation and maternal care in Norway rats. Adv Study Behav. 1996;25:243–94. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stern JM, Johnson SK. Ventral somatosensory determinants of nursing behavior in Norway rats. I. Effects of variations in the quality and quantity of pup stimuli. Physiol Behav. 1990;47:993–1011. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90026-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howie GJ, Sloboda DM, Reynolds CM, Vickers MH. Timing of maternal exposure to a high fat diet and development of obesity and hyperinsulinemia in male rat offspring: same metabolic phenotype, different developmental pathways? J Nutr Metab. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/517384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorski JN, Dunn-Meynell AA, Hartman TG, Levin BE. Postnatal environment overrides genetic and prenatal factors influencing offspring obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R768–R78. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00138.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Del Prado M, Delgado G, Villalpando S. Maternal lipid intake during pregnancy and lactation alters milk composition and production and litter growth in rats. J Nutr. 1997;127:458–62. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, Simar D, Lambert K, Mercier J, Morris MJ. Maternal and postnatal overnutrition differentially impact appetite regulators and fuel metabolism. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5348–56. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howie GJ, Sloboda DM, Kamal T, Vickers MH. Maternal nutritional history predicts obesity in adult offspring independent of postnatal diet. J Physiol. 2009;587:905–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rasmussen KM. Effects of under- and overnutrition on lactation in laboratory rats. J Nutr. 1998;128:390S–3S. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.2.390S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor PD, Khan IY, Lakasing L, Dekou V, O’Brien-Coker I, Mallet AI, et al. Uterine artery function in pregnant rats fed a diet supplemented with animal lard. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:389–98. doi: 10.1113/eph8802495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Priego T, Sánchez J, García A, Palou A, Picó C. Maternal dietary fat affects milk fatty acid profile and impacts on weight gain and thermogenic capacity of suckling rats. Lipids. 2013;48:481–95. doi: 10.1007/s11745-013-3764-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rolls BA, Gurr MI, Van Duijvenvoorde PM, Rolls BJ, Rowe EA. Lactation in lean and obese rats: Effect of cafeteria feeding and of dietary obesity on milk composition. Physiol Behav. 1986;38:185–90. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun B, Song L, Tamashiro KLK, Moran TH, Yan J. Large litter rearing improves leptin sensitivity and hypothalamic appetite markers in offspring of rat dams fed high-fat diet during pregnancy and lactation. Endocrinology. 2014;155:3421–33. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samuelsson AM, Matthews PA, Argenton M, Christie MR, McConnell JM, Jansen EHJM, et al. Diet-induced obesity in female mice leads to offspring hyperphagia, adiposity, hypertension, and insulin resistance: A novel murine model of developmental programming. Hypertension. 2008;51:383–92. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerrish CJ, Alberts JR. Postsuckling behavioral arousal in weanling rats (Rattus norvegicus) J Comp Psychol. 1997;111:37–49. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.111.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Randall PK, Campbell BA. Ontogeny of behavioral arousal in rats: Effect of maternal and sibling presence. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1976;90:453–9. doi: 10.1037/h0077211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall WG, Rosenblatt JS. Suckling behavior and intake control in the developing rat pup. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91:1232–47. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Covasa M, Grahn J, Ritter RC. High fat maintenance diet attenuates hindbrain neuronal response to CCK. Regul Pept. 2000;86:83–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(99)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Covasa M, Ritter RC. Rats maintained on high-fat diets exhibit reduced satiety in response to CCK and bombesin. Peptides. 1998;19:1407–15. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(98)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Covasa M, Ritter RC. Adaptation to high-fat diet reduces inhibition of gastric emptying by CCK and intestinal oleate. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R166–R70. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.1.R166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]