Abstract

The rotating frame longitudinal relaxation MRI contrast, T1ρ, obtained with on-resonance continuous wave (CW) spin-lock field is a sensitive indicator of tissue changes associated with hyperacute stroke. Here, the rotating frame relaxation concept was extended by acquiring both T1ρ and transverse rotating frame (T2ρ) MRI data using both CW and adiabatic hyperbolic secant (HSn, n = 1, 4, or 8) pulses in a rat stroke model of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo). The results demonstrate differences in the sensitivity of spin-lock T1ρ and T2ρ MRI to detect hyperacute ischemia. The most sensitive techniques were CW-T1ρ and T1ρ using HS4 or HS8 pulses. Fitting a two-pool exchange model to the T1ρ and T2ρ MRI data acquired from the infarcting brain indicated time-dependent increase in free water fraction, decrease in the correlation time of water fraction associated with macromolecules and increase in the exchange correlation time. These findings are consistent with known pathology in acute stroke, including vasogenic edema, destructive processes and tissue acidification. Our results demonstrate that the sensitivity of the spin-lock MRI contrast in vivo can be modified using different spin-lock preparation blocks, and that physico-chemical models of the rotating frame relaxation may provide insight into progression of ischemia in vivo.

Keywords: Brain, stroke, adiabatic pulses, T1ρ and T2ρ relaxation

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice to diagnose acute cerebral ischemia owing to the fact that several endogenous contrasts develop upon ischemia. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) of brain water rapidly decreases (Moseley et al. 1990) following compromised cerebral blood flow (CBF). It has been shown that ADC decrease has two CBF thresholds; a small decrease occurs close to CBF of 40 - 50 ml/100 g/min and an extensive one immediately below CBF of 20 ml/100 g/min (Gröhn et al. 2000b; Hossmann 1994). The latter CBF value is close to the threshold for ischemic energy failure (Crockard et al. 1987; Naritomi et al. 1988). Diffusion MRI is part of stroke MRI protocols in clinical settings and provides excellent sensitivity and specificity to acute ischemia (Lythgoe et al. 1997; Mullins et al. 2002). It is a common observation both in stroke patients (Baird et al. 1997) and experimental models for stroke (Meng et al. 2004; Shen et al. 2003) that the volume of hypoperfusion, as determined by perfusion MRI, is larger than the volume displaying lowered diffusion. The so-called diffusion-perfusion mismatch is suggested to predict enlargement of an ischemic lesion.

Detection of acute ischemia by MRI can be accomplished by several other endogenous contrasts than diffusion and perfusion, including T1, T2, T2* and longitudinal relaxation time in the rotating frame (T1ρ). Factors leading to hyperacute T1 prolongation in ischemia have been shown to include both CBF-dependent and CBF-independent components (Calamante et al. 1999; Kettunen et al. 2000). Build up of deoxyhemoglobin shortens T2 and T2* in the hyperacute phase of cerebral ischemia (Calamante et al. 1999; Gröhn et al. 1998). T1ρ obtained by on-resonance continuous wave (CW) spin-lock field has been shown to be a specifically interesting MRI contrast to assess hyperacute cerebral ischemia (Gröhn et al. 1999). This is due to the ability of T1ρ MRI to indicate ischemia as follows: firstly, it reveals tissue response to compromised blood flow almost immediately following a drop of CBF below 20 ml/100 g/min (Gröhn et al. 2000a) and secondly, the increase in absolute parenchymal T1ρ correlates with long-term histological outcome (Gröhn et al. 1999). These factors make T1ρ a very attractive MRI contrast to reveal acute stroke, as it predicts the tissue outcome in the acute phase when therapies based on clot removal and/or neuroprotection are most likely to be beneficial. Despite the limitations imposed by specific absorption rate (SAR) of radiofrequency (RF) energy, T1ρ techniques have been applied to human brain imaging (Gröhn et al. 2005; Michaeli et al. 2006; Wheaton et al. 2004).

Recently the concept of rotating frame relaxation contrasts was extended by exploiting relaxation during adiabatic RF pulses. It was shown that, in biological systems, rotating frame relaxation time constants obtained with adiabatic pulses enable assessment of slow molecular motion with an extended range of correlation times (Michaeli et al. 2005; Michaeli et al. 2006). Sensitivity to slow motion occurs because the rotating frame relaxation time constants are sensitive to magnetic field fluctuations caused by tumbling dipoles at or close to the effective frequency (ωeff) in the rotating frame (the Rabi frequency). The sensitivity of T1ρ to molecular dynamics in the kHz range makes it a practical tool for studying dipolar fluctuations in vivo, to gain information about water dynamics and interactions with endogenous macromolecules (Liepinsh and Otting 1996). Similarly to T1ρ, the transverse relaxation time constant in the rotating frame, T2ρ, is a function of dipolar interactions and is additionally affected by the exchange of protons between different magnetic sites. Adiabatic rotating frame time constants are dependent on the choice of amplitude- and frequency-modulation functions of the adiabatic full passage (AFP) pulse (Michaeli et al. 2005). Therefore, adiabatic rotating frame relaxation rates can be altered by using different modulation functions, which provides a basis to assess changes in different intrinsic tissue parameters probing water dynamics.

The aim of this work was two-fold as follows: firstly, to investigate abilities of various T1ρ and T2ρ MR approaches with inherently differing SARs to reveal hyperacute ischemia in a rat model of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo), and secondly, to evaluate alterations in water spin dynamics during evolving cerebral ischemia using the MR relaxation data in the context of an equilibrium two site exchange (2SX) model (Michaeli et al. 2006).

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (weight ranging from 280 to 320 g) were anesthetized with isoflurane (2.5% during surgery and 1.5 - 2% during MRI) with a constant flow of 70/30 N2O/O2 through a nose cone. Temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo, n = 8) for 90 minutes was induced by the intraluminal thread method (Longa et al. 1989). A satellite group of male Wistar rats (n = 3) were operated similarly as those for temporary MCAo, but leaving the occluder thread in place for permanent MCAo. A sham operated rat was used as a control. Arterial blood gases and pH were analyzed immediately before and during MR data acquisition (i-Stat Co., East Windsor, NJ, USA). The core temperature was monitored online and maintained close to 37°C by warm water circulation in a heating pad placed under the torso. Blood pressure was monitored online during the scanning (CardioCap II, Datex, Helsinki, Finland). All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Laboratory Animal Center of the University of Kuopio.

MRI

MR experiments were performed in a horizontal 4.7 T magnet (Magnex Scientific Ltd., Abingdon, U.K.) interfaced to a Varian Inova console (Varian, Palo Alto, CA, USA). A quadrature half-volume coil consisting of two loops with 20 mm diameters (HF imaging LLC, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was used to transmit RF pulses and to receive MRI signals.

The transversal imaging plane (field of view 2.56 × 2.56 cm2, 128 × 64 points) was positioned so that the center of the slice (thickness 1.5 mm) was 4 mm from the surface of the brain. In the transient MCAo group the MR data were measured once during ischemia (between 60 and 90 minutes after onset of MCAo), followed by retraction of the occluder thread at 90 minutes without moving the animal in the magnet, and three more MR data sets were acquired between 0 - 30, 30 - 60 and finally, 60 - 90 minutes after the onset of reperfusion. In the permanent MCAo group, MRI scans were acquired at two time points; the first set between 120 - 150 minutes and the second between 230 - 260 minutes from induction of ischemia.

Data for the trace of the diffusion tensor (Dav = 1/3 * Trace(D)) map were first collected and used to localize the ischemic tissue (Kettunen et al. 2000). The Dav was quantified using a spin echo MRI sequence incorporating four bipolar gradients along each axis (Mori and van Zijl 1995) with four b-values ranging from 0 to 1370 s/mm2 (time-to-repetition (TR) 1.5 s, time-to-echo (TE) 55 ms).

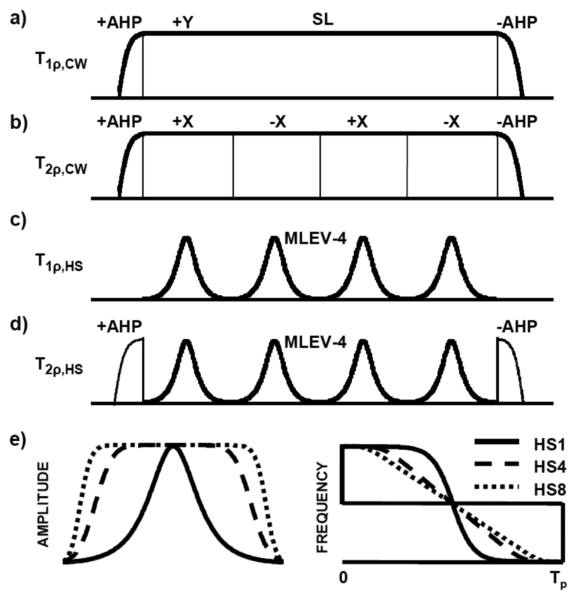

The MRI data for on-resonance T1ρ were collected with a conventional CW-type technique consisting of the following pulse sequence module: adiabatic half passage (AHP) - spin-lock (SL) - reverse AHP (Fig. 1a). This module was immediately followed by a fast spin echo (FSE) readout sequence (echo spacing 10 ms, 16 echoes, center-out k-space filling, TR = 2.5 s). The spin-lock period of the preparation module (Gröhn et al. 2005) ranged from 8 to 64 ms with a target spin-lock amplitude B1,SL = 0.8 G. CW-type T2ρ data were acquired with the following preparation module: AHP - rotary echo - reverse AHP (Solomon 1959) (Fig. 1b). In this CW-T2ρ preparation module, the first AHP pulse created transverse magnetization along the x′ axis of the rotating frame (phase = 0°), and the phases of the subsequent rotary echo pulses alternated between +90° and +270° every 2 ms. A final reverse AHP returned the magnetization to the longitudinal (z′) axis and its magnitude was measured using the FSE readout sequence. Spin-lock lengths and B1 were identical to those used in the CW-T1ρ experiments.

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the preparation pulse sequences: conventional spin-lock T1ρ (a), rotary echo T2ρ (b), T1ρ using HSn pulses (c) and T2ρ using HSn pulses (d). Spin-lock (SL) time in each is 8ms. (e) Amplitude and frequency modulation functions for AFP pulses HS1, HS4 and HS8. AHP = Adiabatic Half Passage

Rotating frame relaxation using adiabatic preparation pulses was measured in a similar manner, except the amplitude and frequency of the spin-lock and rotary echo pulses were modulated under the adiabatic condition. The modulations were based on the hyperbolic secant family of pulses (HSn), using conditions and parameters which achieved magnetization inversion (i.e., adiabatic full passage) (Garwood and DelaBarre 2001; Silver et al. 1984). Under this so-called “adiabatic condition”, the magnetization follows the trajectory of the effective magnetic field vector, Beff. For convenience, the effective field is often expressed in units of angular frequency (rad/s), and as such is given by ωeff = γBeff, where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio. The amplitude and orientation of ωeff are time dependent and these in turn are functions of the amplitude modulations and frequency modulations used for the pulse. One way to alter the modulations is to change the stretching factor, n. Accordingly, the amplitude modulation (AM) function of the HSn pulse becomes flatter as the factor n increases (Fig. 1e), as given by

| (1) |

where is the maximum pulse amplitude in rad/s and β is a constant. When n = 1, the pulse is the original hyperbolic secant pulse (Silver et al. 1984), whereas when n > 1, a stretched version of the pulse is produced (Tannús and Garwood 1996). In the experiments performed here, all HSn pulse parameters were held constant except for the stretching factor (n = 1, 4, or 8). With these adiabatic pulses, the rotating frame relaxation times (i.e., adiabatic T1ρ and adiabatic T2ρ) were measured using a preparation module consisting of consecutive identical HSn pulses, with no delays between pulses (i.e., negligible “RF free” intervals, Fig. 1c). To obtain data for fitting, the number of HSn pulses was increased in separate experiments. Specifically, the train length increased from 4 to 32 pulses, each having a duration of 2 ms. The phases of the HSn pulses were prescribed according to MLEV4 (Levitt et al. 1982). For adiabatic T2ρ measurements, AHP and reverse AHP pulses were added before and after the HSn pulse train, respectively (Fig. 1d). These preparation modules preceded a FSE readout sequence.

Data for T2 maps were collected with the same FSE sequence with a T2 preparation block consisting of AHP - TE/4 - AFP - TE/2 - AFP - TE/4 - reverse AHP. To map the B1 field, data were acquired using a variable length square preparation pulse and a crusher gradient in front of a FLASH pulse sequence (TR 4.5 ms, TE 2.2 ms), and a cosine function was fitted to the measured signal intensity oscillation.

For fitting the 2SX model, more complete T1ρ and T2ρ relaxation data sets using eight different HSn pulses (n = 1, 2, …, 8) were acquired from a satellite group of permanent MCAo rats at two time points between. A sham operated animal was used as control to the permanent ischemia group.

Data analysis

All data analyses were performed with Matlab (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Regions of interest (ROIs) were positioned to cover the ipsilateral striatum, which represents the core of the ischemic region, and the corresponding contralateral area. To evaluate whether the MRI contrasts used in this study could detect spatiotemporal progression during MCAo and reperfusion, a threshold based analysis was performed. The threshold was set to be 15% above (or below for diffusion) the mean value in contralateral ROI consisting of entire striatum and cortex and number of pixels above (or below for diffusion) this were calculated both in contralateral and corresponding ipsilateral ROIs. The difference (ipsi-contra) in the number of pixels passing threshold in ROIs were calculated and assumed to represent the amount of abnormal pixels. All results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Paired Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis of data obtained from ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres.

Under the intermediate and slow exchange conditions non-monoexponential MR signal intensity (SI) decay is detected. In our experiments mono exponential SI decay was observed, within the range of spin-lock times used, and therefore fast exchange condition was assumed. For the interpretation of NMR data the dynamic processes were modeled with an equilibrium 2SX system approximation, comprising of two water populations coupled by an equilibrium exchange as follows: ‘A’ is the water population associated with macromolecules, and ‘B’ is the free water population. These two sites have relaxation times T1ρ,A and T1ρ,B that maintain equilibrium during RF pulse. At the two exchanging sites, the relaxation rate constants are modulated since ωeff is time-dependent. Thus, the sensitivity to different correlation times changes during the RF pulse. The formalism is detailed in the Appendix.

The fundamental MR parameters, i.e., correlation times at specific sites A and B (τc,A and τc,B), the relative spin populations (PA and PB), and the exchange correlation time (τex), were estimated by fitting the 2SX model into the R1ρ,obs and R2ρ,obs measurements from each animal using the Levenberg-Marquardt nonlinear least squares regression algorithm. The fittings were performed using combined R1ρ,obs and R2ρ,obs data to find a set of parameters that optimally fit the measured data. To reduce the number of fitted parameters and to keep fitting unambiguous, the correlation time of free water τc,B and the chemical shift difference δω between exchanging sites were assumed to be 10-12 s and 125 Hz, respectively (Sierra et al. 2008). The resulting parameter estimates were averaged and tested for statistical significance using two-tailed two-sample Student's t-test.

Results

During the MCAo experiments physiological parameters were within the physiological range except pCO2, which was slightly elevated (Table 1). Mild hypercapnia is commonly observed in spontaneously breathing animals under prolonged isoflurane anesthesia.

Table 1.

Physiological parameters for sham operated and stoke rats during MCAo and 30 minutes post occlusion. Values are mean ± SD.

| pCO2 [mmHg] | pO2 [mmHg] | pH | BPmean [mmHg] | Temp [°C] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCAo | 49 ± 9 | 99 ± 21 | 7.35 ± 0.05 | 117 ± 13 | 36.2 ± 1.1 |

| Post occlusion | 52 ± 6 | 121 ± 27 | 7.33 ± 0.04 | 113 ± 13 | 36.7 ± 0.6 |

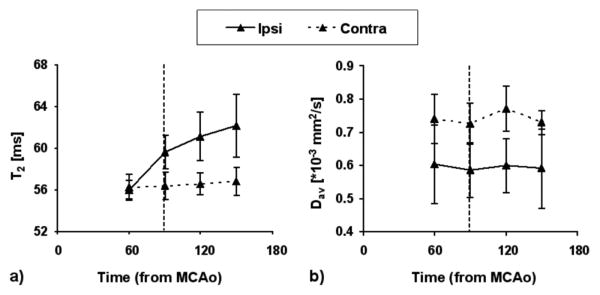

Dav decreased by approximately 20% by 60 minutes of MCAo ipsilaterally consistent with severe ischemia and it did not recover upon retraction of the MCA occluder (Fig. 2b). T2 was not significantly different between ipsilateral and contralateral brain by 60 minutes (Fig. 2a), but showed prolonged values at 90 minutes of MCAo and T2 continued to rise despite the retraction of the occluder.

FIG. 2.

T2 (a) and diffusion (Dav) (b) values for ischemic (‘ipsi’) and contralateral (‘contra’) sides of the brain. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Vertical dotted line denotes the time of occluder removal.

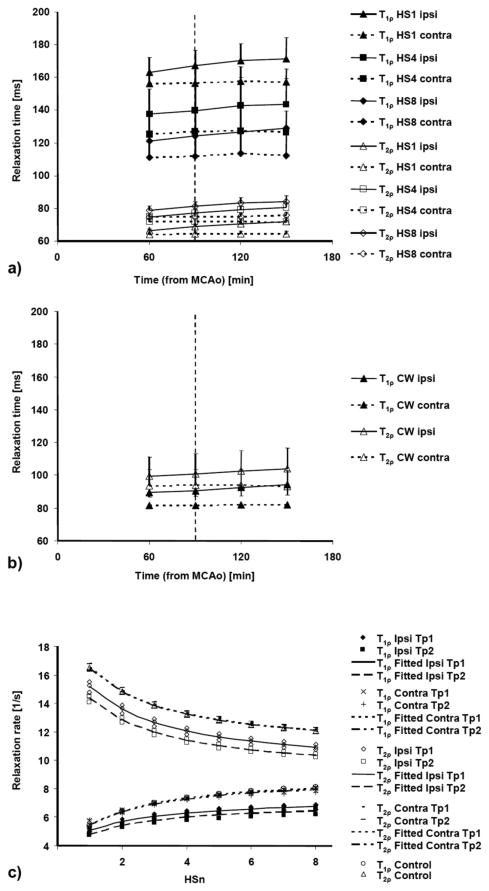

T1ρ measured with HSn pulses from normal brain decreased with increasing n, while T2ρ behaved in the opposite manner (Fig. 3a). All T1ρ relaxation time constants obtained with HSn pulses (values ranging from 100 - 180 ms) were longer than those with CW measurements (ranging from 80 - 100 ms). In contrast, the T2ρ values acquired with HSn pulses (T2ρ,HSn) were shorter (ranging from 60 to 85 ms; Fig. 3a) than those obtained with the CW-technique (ranging from 80 to 115 ms; Fig. 3b).

FIG. 3.

T1ρ and T2ρ values measured using HSn pulses (a) and CW pulses (b) for ischemic (‘ipsi’) and contralateral (‘contra’) brain. Data are shown as mean ± SD and obtained from animals with transient MCA occlusion. R1ρ and R2ρ values (c) measured with HSn (n = 1 to 8) for ischemic (‘ipsi’) and contralateral (‘contra’) brain from all three animals with permanent MCA occlusion and a control rat. The fitted lines for two time points (Tp1 = 120 - 150 min after MCAo, Tp2 = 230 - 260 min after MCAo) were calculated using the measured T1ρ and T2ρ values as described in Methods.

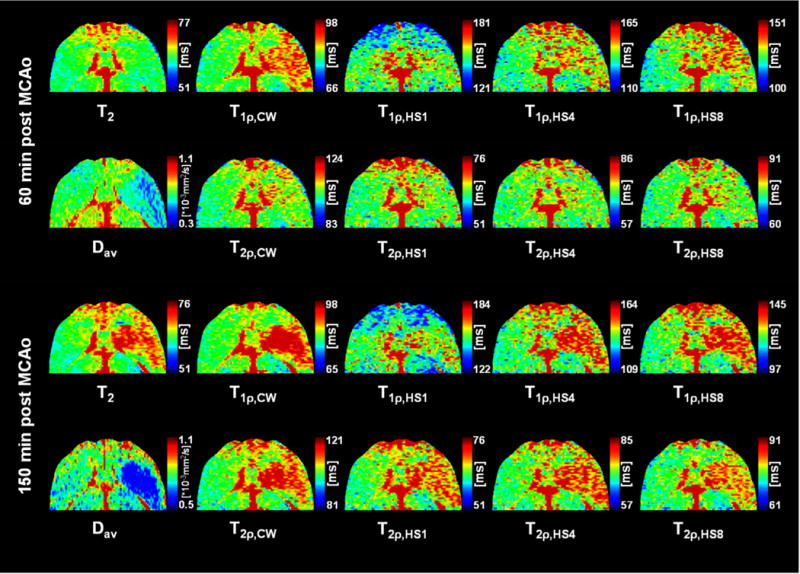

By 60 minutes of MCAo, all ipsilateral T1ρ and T2ρ values increased relative to the contralateral ones and T2ρ remained constant throughout the MRI observation time (Fig. 3a and b). All rotating frame relaxation times significantly differed between ipsi- and contralateral sides (p < 0.005) at all time points during stroke. The rotating frame relaxation times most sensitive to ischemic changes in the core of the lesion were T1ρ,CW, T1ρ,HS4 and T1ρ,HS8, all showing increased values by 9 - 10% by 60 minutes and by 13 - 15% by 150 minutes after induction of MCAo, respectively (Table 2). Figure 4 shows an example of the calculated parametric maps acquired at 60 - 90 minutes post MCAo and at 90 - 120 minutes after reperfusion began.

Table 2.

Average difference between the ischemic and contralateral side of ΔT1ρ and ΔT2ρ relaxation times, diffusion (ΔDav) and ΔT2. Values are in per cent (mean ± SD).

|

ΔT1ρ [%]

|

ΔT2ρ [%]

|

ΔT1ρ [%]

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CW | CW | HS1 | HS4 | HS8 | |

| 60-90min | 9 ± 4** | 6 ± 3** | 4 ± 3** | 10 ± 3** | 9 ± 4** |

| 90-120min | 11 ± 5** | 7 ± 5** | 7 ± 3** | 10 ± 5** | 11 ± 6** |

| 120-150min | 13 ± 7** | 9 ± 6** | 8 ± 2** | 12 ± 7** | 12 ± 7** |

| 150-180min | 15 ± 8** | 11 ± 5** | 9 ± 4** | 13 ± 7** | 15 ± 7** |

|

| |||||

| ΔT2ρ [%] | |||||

|

|

|||||

| HS1 | HS4 | HS8 | ΔDav [%] | ΔT2 [%] | |

|

| |||||

| 60-90min | 4 ± 3** | 4 ± 2** | 5 ± 2** | -19 ± 12** | 0 ± 3 |

| 90-120min | 7 ± 3** | 7 ± 4** | 8 ± 3** | -20 ± 8** | 6 ± 3** |

| 120-150min | 10 ± 4* | 10 ± 4** | 11 ± 3** | -22 ± 11** | 8 ± 3** |

| 150-180min | 11 ± 5** | 12 ± 5** | 11 ± 5** | -19 ± 16* | 9 ± 5** |

Significance was calculated by Student's t-test (

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01)

FIG. 4.

Representative relaxation and diffusion maps acquired at 60 - 90 minutes during MCA occlusion and 60 - 120 minutes after beginning of reperfusion (after 90 minutes of occlusion) showing the difference in contrast between the contralateral (left) and ischemic (right) rat striatum. Color scaling is adjusted to ± 20% of the contralateral striatum in all relaxation maps for easier comparison. Schematic brain outline adapted from Paxinos and Watson 1998.

When ROI analysis focused on the core of the lesion, threshold based analysis was also performed to assess spatial progression or recovery in the periphery of the lesion (Fig. 5). Diffusion and all measured relaxation times, except T2 in the first measurement point, showed increased number of abnormal pixels in the ipsilateral side compared to the contralateral side. Importantly, spatiotemporal progression was evident from the increasing number of pixels in T1ρ,CW, T2ρ,CW, T2ρ,HSn and in T2 contrasts while diffusion showed significantly decreased lesion area during reperfusion. These data demonstrate the complementary nature of these MR parameters to evaluate post-ischemic brain tissue.

FIG. 5.

Threshold analysis showing the progression of the lesion area at four time points after MCAo. Data are presented as difference (ipsi-contra) in the number of pixels in striatum and cortex with values over 115% (or under 85% for diffusion) of the mean value in contralateral side (for details see Methods). Data are shown as mean ± SD. Significance is shown as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, different from zero; + p < 0.05, ++ p < 0.01, different from the first time point.

For the quality control, possible spatial variation of the B1 field within the field of view was determined by means of B1 maps. The average γB1 measured with the same transmitter power settings as used for rotating frame relaxation measurements, was 3130 ± 40 Hz (i.e. B1 = 0.74 ± 0.01 G) in ROIs covering the ischemic lesion. The mean difference between ipsi- and contralateral sides was -1.1 ± 0.4%, demonstrating insignificant B1 variation between the hemispheres.

MRI data from the permanent MCAo rats were fitted to the equilibrium 2SX model (Michaeli et al. 2006) to assess changes in water dynamics during evolution of ischemia (Fig. 3c). Using the combined HSn (n = 1 to 8) T1ρ and T2ρ MR data as input, the 2SX model revealed increasing difference between ipsi- and contralateral sides in the fitted parameters during progression of ischemia (Table 3). The relative size of the free water pool (site B) increased significantly during MCAo. At the same time, the rotational correlation time τc,A showed drastic decrease indicating increased mobility of the bound water fraction. On the other hand, τex increased in the brain parenchyma following induction of ischemia.

Table 3.

Averaged fitted model parameters of the adiabatic T1ρ and T2ρ of water pools (averaged parameter values ± standard deviation) for contralateral and ipsilateral sides at two time points (Tp 1 = 120 - 150 and Tp 2 = 230 - 260 min after MCAo). Statistically significant changes were observed between contralateral and ipsilateral sides (*p < 0.05, two-sample two-tailed Student's t-test).

| PA | PB | τc,A [s] | τex [s] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contra | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.62 ± 0.02 | (6.4 ± 1.3) × 10-10 | (6.6 ± 0.2) × 10-5 |

| Ipsi Tp 1 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | (4.0 ± 0.9) × 10-10* | (7.3 ± 0.1) × 10-5* |

| Ipsi Tp 2 | 0.34 ± 0.02* | 0.66 ± 0.02* | (4.3 ± 1.1) × 10-10* | (7.01 ± 0.03) × 10-5* |

Discussion

We examined the abilities of the adiabatic modulation functions and conventional CW-type RF pulses to generate rotating frame relaxation MR contrast for detection of hyperacute brain ischemia. It was observed that the adiabatic HS pulses used provide T1ρ or T2ρ relaxation time constants with inherent differences to detect time dependent changes in acute stroke. Fitting the equilibrium 2SX model into the rotating frame relaxation data indicated substantial changes in the pool sizes, mobility and exchange times of cerebral water pools during the evolution of ischemia. These data are taken to provide an insight into the physico-chemical mechanisms underpinning the observed MR relaxation changes occurring in stroke.

In normal brain parenchyma, CW-T1ρ was found to be shorter than T1ρ acquired with HSn pulses. T1ρ relaxation times measured with HSn pulses became shorter with increasing n of HS pulses in contrast to T2ρ relaxation times, which behaved in the opposite fashion. These observations are consistent with the previous results from human brain and water/ethanol studies by Michaeli et al. (Michaeli et al. 2004; Michaeli et al. 2006). Our data demonstrate that rotating frame relaxation in vivo is indeed influenced by the choice of pulse modulation functions. Specifically, the effective spin-lock frequency with the HSn pulses (ωeff(t)) is off- resonance during a significant portion of the pulse duration, so the method therefore probes more of the shorter correlation time regime of molecular motion than the on-resonance CW-type technique (Gröhn et al. 2003).

Our results show that CW-T1ρ and T1ρ measured with HS4 and HS8 pulses provide a sensitive means to reveal brain ischemia. Our earlier work demonstrates greater sensitivity of the on-resonance spin-lock than the off-resonance T1ρ to the tissue changes caused by ischemia during MCAo (Gröhn et al. 2003). In this regard the current data are in agreement with the previous observations (Gröhn et al. 2003). Especially, during adiabatic pulse modulation using HSn pulses, as n decreases in the HSn-type technique, the spins experience an effective field that is off resonance during a greater portion of each pulse, which creates a less sensitive situation to detect acute stroke than what is obtained with CW-T1ρ.

The sensitivity difference between T1ρ and T2ρ MRI to acute stroke could be considered being analogous to the established one between T1ρ and T2. T1ρ relaxation time is elevated in the early minutes of ischemia, whereas increase in T2 lags much behind. T1ρ is predominantly sensitive to dipolar interactions at the specific sites and isochronous exchange, i.e., the exchange of spins between sites with the same chemical shift, but with relaxation time constants that differ between sites: T1ρ,A ≠ T1ρ,B. As compared with T2ρ, the value of T1ρ is less influenced by anisochronous mechanisms that are thought to arise from dynamic processes on a microscopic scale, such as water diffusing between sites having different magnetic susceptibilities and/or exchange of spins between chemical environments with different chemical shifts. With both T1ρ techniques (CW- and HSn-type), the influence of the latter types of frequency shifts on the measured T1ρ are at least partially “suppressed” by the effective locking field. This may be the main reason for the sensitivity of T1ρ to water-protein interactions and to isochronous exchange. Due to suppression of magnetic susceptibility effects from the T1ρ relaxation, the sensitivity of T1ρ to Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) (Gröhn et al. 1998) is small. On the other hand, the anisochronous mechanisms significantly contribute to the T2ρ relaxation. It has recently been shown that T2ρ can be used to probe iron accumulation in the substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease (Michaeli et al. 2007) and potentially is able to differentiate patients with Parkinson's disease from age-matched controls on an individual basis. The work involving iron content in the brain implies that T2ρ is sensitive to susceptibility effects in vivo.

Inherent properties of T1ρ and T2ρ together with the physico-chemistry of ischemic tissue may reconcile their differences in revealing acute stroke. An almost immediate drop of temperature by 2 - 3°C in the ischemic core (Gröhn et al. 1999) and acidification of tissue is expected to decrease contributions of the anisochronous mechanisms to the relaxation. Anisochronous effects may not be significant for the T1ρ relaxation (Abragam 1961; Michaeli et al. 2006), but they may contribute to the T2ρ relaxation.

One of the motivations behind this study was to search for alternative approaches to the CW-T1ρ technique in order to lower SAR, a factor that limits the clinical applicability of the rotating frame MR techniques (Wheaton et al. 2004). We used a relatively high spin-lock amplitude of 0.8 G, as contrast between ischemic and normal brain tissue with CW-T1ρ has been shown to be a function of the spin-lock amplitude (Gröhn et al. 2000a; Kettunen et al. 2005). Recently, spin-lock amplitudes of ∼0.2 G in 4 T (Gröhn et al. 2005) and 0.12 G in 1.5 T (Borthakur et al. 2004) have been used in human head MRI. With the higher spin-lock power it is difficult to reach full brain coverage required for clinical MRI. Evidently, the HSn-type method produces lower SAR values than the equivalent CW-type method. We calculate that, compared to the CW-T1ρ method, the SAR was lower by 81%, 37%, and 21% when scans were acquired with HS1, HS4 or HS8 pulses respectively, with the same ω1max. To our dissatisfaction, HSn pulses with high n are needed to produce MR contrast able to detect acute ischemia, partially counteracting the SAR advantage. In practice, the difference between SARs in the CW- and HSn-techniques is slightly smaller, when longer relaxation times with the HSn-technique compared to the CW-approach are accounted for, as the HSn-technique requires longer spin-lock times to obtain comparable contrast.

The MRI contrast detected between ischemic and normal tissue with the most sensitive rotating frame relaxation approach at 1 - 3 hours after onset of stroke was comparable in size to the decrease in diffusion coefficient. It should be noted that this is typically the earliest time point when stroke patients are examined with MRI and often shows significant diffusion perfusion mismatch (Baird et al. 1997; Meng et al. 2004; Shen et al. 2003) as a sign of tissue at risk of infarction. It has been shown both in animal models (Gröhn et al. 1999; Minematsu et al. 1992) and in human stroke patients (Doege et al. 2000) that the original diffusion abnormality can transiently recover, notwithstanding the evolving lesion. Also, T1ρ measured during the early hours of ischemia has been shown to better correlate with cell death (Gröhn et al. 1999). Furthermore, T1ρ progressively increases during the first hours of stroke, while diffusion remains at a constant low value, showing that these two MR contrasts probe different aspects of ischemia. These known features of diffusion and rotating frame relaxation data were supplemented by results from threshold analysis in the present study: decreased area of diffusion abnormality was seen during reperfusion while many of the rotating frame relaxation contrasts used as well as T2 were able to highlight progression of the lesion. Data from this and other experimental stroke studies (Gröhn et al. 1999; Gröhn et al. 2000a; Mäkelä et al. 2002) suggest that rotating frame relaxation contrasts could be exploited to estimate the age and severity of the ischemia in the brain parenchyma, and thus, may provide complementary information to the current clinically used MRI techniques. In this way, rotating frame relaxation contrasts can potentially facilitate attempts to predict outcome following brain ischemia (Shen et al. 2005; Wu et al. 2007).

The 2SX model was used to extract information from different water pools during evolution of acute ischemic stroke. It should be realized that such models created to describe water dynamics in tissue are often oversimplified and thus, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results in terms of true cerebral water pools. Two-pool model has often been utilized in the context of magnetization transfer (Henkelman et al. 1993; McConnell 1958). In this model, the immobile fraction is named “semi-solid pool” and it includes protons in macromolecules within tissue that have a T2 relaxation time in the order of 10 μs (Henkelman et al. 1993) and a typical τc in the range of 10-3 - 10-6 s. In the present study the more immobile fraction is named “water associated with macromolecules” and has an effective τc in the order of 10-9 s indicating much higher mobility. Accordingly, the pool size for semi-solid pool in MT based models is typically between 3 - 15% (Mäkelä et al. 2002; Portnoy and Stanisz 2007; Sled and Pike 2001) while we obtained 34 - 38% for this pool. We initially tried to constrain the pool sizes in the 2SX model fitting to be more in line with MT literature, but this resulted in a physically impossible (negative) parameter estimate for the exchange correlation time. Therefore, it is evident that these two models describe behavior of different water pools in vivo and results obtained by modeling of Z-spectra data from MT experiments cannot be directly compared to those of the present study.

The results obtained from the 2SX model agree with pathophysiology of ischemia, justifying discussion concerning the mechanisms contributing to these early relaxation changes. Recently, acute T1 relaxation changes were linked to increased water content (increase by 2.3% by 2 hours of ischemia) in tissue during acute cerebral ischemia (Barbier et al. 2005). Similarly, an increase in the amount of MT has been associated with elevated water content in ischemic tissue (Mäkelä et al. 2002). Interestingly, we observed an increase by some 2% in relative size of free water pool about two hours after MCAo. It should be stressed, however, that our results indicate that not only water content, but also other factors may contribute to the prolongation of rotating frame relaxation times in ischemic tissue. Our results show a very pronounced decrease (38%) of the correlation time of the water pool associated with macromolecules and an increase (11%) of the exchange correlation time. It is well known that the collapse of cerebral energy state leads to complex biochemical cascades involving the activation of proteases and other destructive processes. It seems reasonable to speculate that decreased correlation time is associated with the accumulation of protein fragments that arise during proteolysis (Ewing et al. 1999). The increase in exchange time may be caused by the concerted actions of temperature decline and pH decline. Proton exchange rate decreases in acute ischemia for the majority of exchangeable groups in proteins when pH drops from 7.1 to close to 6 (Jokivarsi et al. 2007; Liepinsh and Otting 1996). However, it should be noted that the exchange term in the present model includes not only chemical exchange but also a broad variety of different exchange phenomena. Furthermore, a fixed value for δω was used in the fitting. However, it cannot be ruled out that a possible change in δω during acute ischemia could have contributed to the fitting results.

To summarize, T1ρ measured using either a CW on-resonance pulse or HSn pulses with high n proved to be the most sensitive for acute ischemic stroke. The relaxation changes are likely to be associated with increased tissue water content, an increase in the water pool associated with macromolecules, and a change in exchange behaviour of water molecules. Sensitivity of T1ρ MRI techniques is comparable to diffusion MRI at clinically relevant time points after onset of ischemia and the combined use of these MRI techniques may facilitate evaluation of the time of the onset of stroke and reversibility of the tissue damage (Shen et al. 2005). Recently, T1ρ and T2ρ MRI techniques have shown to bear great potential for diagnostic assessment of chronic neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson's disease (Michaeli et al. 2007) and Alzheimer's disease (Borthakur et al. 2006).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation (TEKES), the Emil Aaltonen Foundation, the Finnish Cultural Foundation of Northern Savo and NIH grants P41 RR008079 and P30 NS057091.

The authors thank Ms Maarit Pulkkinen for expert technical assistance and Mr Nick Hayward for proofreading and editing the manuscript.

Appendix

During an adiabatic pulse the orientation of the effective frequency vector ωeff(t) changes, as described by the angle α(t) between ωeff(t) and the z′ axis,

| (2) |

where ω1(t) is the AM function of the RF pulse, ωRF(t) is the time-dependent frequency of the RF pulse, and ω0 is the Larmor precession frequency. The time-dependent magnitude of the effective frequency vector is given by,

| (3) |

In accordance with the 2SX model, with two water populations (PA and PB, where PA + PB = 1) coupled by equilibrium exchange, the rate constant describing longitudinal rotating frame relaxation (R1ρ,obs=(T1ρ,obs)-1) during an adiabatic pulse is given by (Michaeli et al. 2004; Sorce et al. 2006)

| (4) |

where TP is the length of individual pulses. Contributions from dipolar fluctuations (first and second terms of Eq. (4)) can be calculated from

| (5) |

where

| (6) |

and exchange-induced relaxation (third term in Eq. 4) is given by

| (7) |

For transverse rotating frame relaxation, the rate constant (R2ρ,obs = 1/T2ρ,obs) can be written as (Michaeli et al. 2004)

| (8) |

where

| (9) |

and the exchange relaxation rate constant is given by:

| (10) |

Here δω is the chemical shift difference between sites A and B, τc is the correlation time for sites A and B (τc,A and τc,B, respectively), and τex the exchange correlation time (the mean lifetime of the exchanging species at the two sites), r is the internuclear distance (1.58 Å for water), I and γ are the equivalent spin and gyromagnetic ratio of the nucleus, respectively, and (x00127) is Planck's constant (Blicharski 1972; Michaeli et al. 2005).

For the spin-lock steady-state relaxation (or instantaneous approximation for adiabatic rotation), the time dependence from the above equations can be ignored. Furthermore, for the on-resonance case (i.e. α = π/2), the R1ρ,obs and R2ρ,obs can be written as

| (11) |

| (12) |

where

| (13) |

| (14) |

and the exchange-induced relaxation rate constants are given by

| (15) |

| (16) |

References

- Abragam A. The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism. Oxford: The Clarendon Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Baird AE, Benfield A, Schlaug G, Siewert B, Lövblad K-O, Edelman RR, Warach S. Enlargement of human cerebral ischemic lesion volumes measured by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:581–589. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier EL, Liu L, Grillon E, Payen JF, Lebas JF, Segebarth C, Remy C. Focal brain ischemia in rat: acute changes in brain tissue T1 reflect acute increase in brain tissue water content. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:499–506. doi: 10.1002/nbm.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blicharski J. Nuclear magnetic relaxation in rotating frame. Acta Phys Pol A. 1972;41:223–236. [Google Scholar]

- Borthakur A, Gur T, Wheaton AJ, Corbo M, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Reddy R. In vivo measurement of plaque burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:1011–1017. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthakur A, Wheaton AJ, Gougoutas AJ, Akella SV, Regatte RR, Charagundla SR, Reddy R. In vivo measurement of T1rho dispersion in the human brain at 1.5 tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19:403–409. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamante F, Lythgoe MF, Pell GS, Thomas DL, King MD, Busza AL, Sotak CH, Williams SR, Ordidge RJ, Gadian DG. Early changes in water diffusion, perfusion, T1, and T2 during focal cerebral ischemia in the rat studied at 8.5 T. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:479–485. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199903)41:3<479::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockard HA, Gadian DG, Frackowiak RSJ, Proctor E, Allen K, Williams SR, Russell RWR. Acute cerebral ischaemia: concurrent changes in cerebral blood flow, energy metabolites, pH, and lactate measured with hydrogen clearance and 31P and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. II. Changes during ischaemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1987;7:394–402. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1987.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doege CA, Kerskens CM, Romero BI, Brunecker P, Junge-Hulsing J, Muller B, Villringer A. MRI of small human stroke shows reversible diffusion changes in subcortical gray matter. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2021–2024. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200006260-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JR, Jiang Q, Boska M, Zhang ZG, Brown SL, Li GH, Divine GW, Chopp M. T1 and magnetization transfer at 7 Tesla in acute ischemic infarct in the rat. Magn Reson Med. 1999;41:696–705. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199904)41:4<696::aid-mrm7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garwood M, DelaBarre L. The return of the frequency sweep: designing adiabatic pulses for contemporary NMR. J Magn Reson. 2001;153:155–177. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröhn H, Michaeli S, Garwood M, Kauppinen R, Gröhn O. Quantitative T(1rho) and adiabatic Carr-Purcell T2 magnetic resonance imaging of human occipital lobe at 4 T. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:14–19. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröhn O, Mäkelä H, Lukkarinen J, DelaBarre L, Lin J, Garwood M, Kauppinen R. On- and off-resonance T(1rho) MRI in acute cerebral ischemia of the rat. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:172–176. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröhn OH, Lukkarinen JA, Oja JM, van Zijl PC, Ulatowski JA, Traystman RJ, Kauppinen RA. Noninvasive detection of cerebral hypoperfusion and reversible ischemia from reductions in the magnetic resonance imaging relaxation time, T2. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:911–920. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199808000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröhn OH, Lukkarinen JA, Silvennoinen MJ, Pitkänen A, van Zijl PC, Kauppinen RA. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging assessment of cerebral ischemia in rat using on-resonance T1 in the rotating frame. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:268–276. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199908)42:2<268::aid-mrm8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröhn OHJ, Kettunen MI, Mäkelä HI, Penttonen M, Pitkänen A, Lukkarinen JA, Kauppinen RA. Early detection of irreversible cerebral ischemia in the rat using dispersion of the MRI relaxation time, T1ρ. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000a;20:1457–1466. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gröhn OHJ, Kettunen MI, Penttonen M, Oja JME, van Zijl PCM, Kauppinen RA. Graded reduction of cerebral blood flow in rat as detected by the nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation time T2: A theoretical and experimental approach. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000b;20:316–326. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200002000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkelman RM, Huang X, Xiang Q-S, Stanisz GJ, Swanson SD, Bronskill MJ. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29:759–766. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossmann KA. Viability thresholds and the penumbra of focal ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:557–565. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokivarsi KT, Gröhn HI, Gröhn OH, Kauppinen RA. Proton transfer ratio, lactate, and intracellular pH in acute cerebral ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:647–653. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen MI, Gröhn OHJ, Lukkarinen JA, Vainio P, Silvennoinen MJ, Kauppinen RA. Interrelations of T1 and diffusion of water in acute cerebral ischemia of the rat. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:833–839. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200012)44:6<833::aid-mrm3>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettunen MI, Kauppinen RA, Gröhn OHJ. Dispersion of cerebral on-resonance T1 in the rotating frame (T1 rho) in global ischaemia. Appl Magn Reson. 2005;29:89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M, Freeman B, Frenkiel T. Broadband heteronuclear decoupling. J Magn Reson. 1982;47:328–330. [Google Scholar]

- Liepinsh E, Otting G. Proton exchange rates from amino acid side chains-implications for image contrast. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:30–42. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lythgoe MF, Busza AL, Calamante F, Sotak CH, King MD, Bingham AC, Williams SR, Gadian DG. Effects of diffusion anisotropy on lesion delineation in a rat model of cerebral ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:662–668. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä H, Kettunen M, Gröhn O, Kauppinen R. Quantitative T(1rho) and magnetization transfer magnetic resonance imaging of acute cerebral ischemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:547–558. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell HM. Reaction Rates by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1958;28:430–431. [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Fisher M, Shen Q, Sotak CH, Duong TQ. Characterizing the diffusion/perfusion mismatch in experimental focal cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:207–212. doi: 10.1002/ana.10803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaeli S, Grohn H, Grohn O, Sorce DJ, Kauppinen R, Springer CS, Jr, Ugurbil K, Garwood M. Exchange-influenced T2rho contrast in human brain images measured with adiabatic radio frequency pulses. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;53:823–829. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaeli S, Oz G, Sorce DJ, Garwood M, Ugurbil K, Majestic S, Tuite P. Assessment of brain iron and neuronal integrity in patients with Parkinson's disease using novel MRI contrasts. Mov Disord. 2007;22:334–340. doi: 10.1002/mds.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaeli S, Sorce DJ, Idiyatullin D, Ugurbil K, Garwood M. Transverse relaxation in the rotating frame induced by chemical exchange. J Magn Reson. 2004;169:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaeli S, Sorce DJ, Springer CS, Jr, Ugurbil K, Garwood M. T1rho MRI contrast in the human brain: modulation of the longitudinal rotating frame relaxation shutter-speed during an adiabatic RF pulse. J Magn Reson. 2006;181:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minematsu K, Li L, Sotak CH, Davis MA, Fisher M. Reversible focal ischemic injury demostrated by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in rats. Stroke. 1992;23:1304–1311. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.9.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, van Zijl PCM. Diffusion weighting by the trace of the diffusion tensor within a single scan. Magn Reson Med. 1995;33:41–52. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley ME, Cohen Y, Mintorovitch J, Chileuitt L, Shimizu H, Kucharczyk J, Wendland MF, Weinstein PR. Early detection of regional cerebral ischemia in cats: comparison of diffusion- and T2-weighted MRI and spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:330–346. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins ME, Schaefer PW, Sorensen AG, Halpern EF, Ay H, He J, Koroshetz WJ, Gonzalez RG. CT and conventional and diffusion-weighted MR imaging in acute stroke: study in 691 patients at presentation to the emergency department. Radiology. 2002;224:353–360. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2242010873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naritomi H, Sasaki M, Kanashiro M, Kitani M, Sawada T. Flow thresholds for cerebral energy disturbance and Na+ pump failure as studied by 31P and 23Na NMR spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1988;8:16–23. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy S, Stanisz GJ. Modeling pulsed magnetization transfer. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:144–155. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Meng X, Fisher M, Sotak CH, Duong TQ. Pixel-by-pixel spatiotemporal progression of focal ischemia derived using quantitative perfusion and diffusion imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1479–1488. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000100064.36077.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Ren H, Fisher M, Duong TQ. Statistical prediction of tissue fate in acute ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:1336–1345. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A, Michaeli S, Niskanen J-P, Valonen PK, Gröhn HI, Ylä-Herttuala S, Garwood M, Gröhn OH. Water spin dynamics during apoptotic cell death in glioma gene therapy probed by T1rho and T2rho. Magn Reson Med. 2008 doi: 10.1002/mrm.21600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver MS, Joseph RI, Hoult DI. Highly selective π/2 and π pulse generation. J Magn Reson. 1984;59:347–351. [Google Scholar]

- Sled JG, Pike GB. Quantitative imaging of magnetization transfer exchange and relaxation properties in vivo using MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:923–931. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon I. Rotary Spin Echoes. Phys Rev Lett. 1959:2, 301–302. [Google Scholar]

- Sorce DJ, Michaeli S, Garwood M. The time-dependence of exchange-induced relaxation during modulated radio frequency pulses. J Magn Reson. 2006;179:136–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannús A, Garwood M. Improved performance of frequency-swept pulses using offset-independent adiabaticity. J Magn Reson A. 1996;120:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton AJ, Borthakur A, Corbo M, Charagundla SR, Reddy R. Method for reduced SAR T1rho-weighted MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:1096–1102. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu O, Sumii T, Asahi M, Sasamata M, Ostergaard L, Rosen BR, Lo EH, Dijkhuizen RM. Infarct prediction and treatment assessment with MRI-based algorithms in experimental stroke models. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:196–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]