Abstract

Background

Rates of hospital admission are increasing, particularly among older people. Poor health behaviours cluster but their combined impact on risk of hospital admission among older people in the UK is unknown.

Methods

2997 community-dwelling men and women (aged 59-73) participated in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS). We scored (from 0-4) number of poor health behaviours engaged in at baseline (1998-2004) out of: current smoking, high weekly alcohol, low customary physical activity and poor diet. We linked HCS with Hospital Episode Statistics and mortality data to 31/03/2010 and analysed associations between the score and risk of different types of hospital admission: any; elective; emergency; long stay (>7 days); 30-day readmission (any, or emergency).

Results

32%, 40%, 20% and 7% of men engaged in zero, one, two, and three/four poor health behaviours; corresponding percentages for women 51%, 38%, 9%, 2%. 75% of men (69% women) experienced at least one hospital admission. Among men and women, increased number of poor health behaviours was strongly associated (p<0.01) with greater risk of long stay and emergency admissions, and 30-day emergency readmissions. Hazard ratios for emergency admission for three/four poor health behaviours in comparison with none were: men, 1.37[95%CI:1.11,1.69]; women, 1.84[95%CI:1.22,2.77]. Associations were unaltered by adjustment for age, BMI and comorbidity.

Conclusions

Clustered poor health behaviours are associated with increased risk of hospital admission among older people in the UK. Lifecourse interventions to reduce number of poor health behaviours could have substantial beneficial impact on health and use of healthcare in later life.

Keywords: health behaviours, hospitalisation, hospital admissions, hospital episode statistics, older people

INTRODUCTION

The National Health Service (NHS) is under pressure in the face of an ageing population.[1] People aged 65 years and older constituted 17% of the UK population in 2013[2] but account for 66% of people admitted to hospital[3] and admissions have increased rapidly in this age group[1]. Moreover, older people experience longer hospital stays and higher rates of readmission than younger people[3]. It is projected that people aged 65 years and over will comprise 23% of the UK population by 2035[4]; this increase will place even greater demand on the NHS. Set against this backdrop, improved understanding of the patterns and risk factors of hospitalisation among older people is required; this would inform understanding of current demand on the NHS by identifying subgroups of older people who are at risk of ill health, and could contribute to the development of interventions designed to reduce the need for hospitalisation in future generations of older people.

Smoking, excessive alcohol use, low levels of physical activity and poor diet are risk factors for ill health and premature mortality. Almost half of the burden of disease in developed countries is attributable to these behavioural risk factors[5] and they have a major impact on ill-health in the UK population.[6] Even in old age, poor health behaviours are associated with reduced longevity, independent of chronic conditions.[7] Public Health England recognises that reducing smoking and harmful drinking, and increasing levels of physical activity and improving diet, are important public health priorities.[8] In recent years, health promotion strategies have started to incorporate a whole person approach to behaviour change; exemplar initiatives include Every Contact Counts[9] and Change4Life.[10] However, this shift of emphasis follows on from years in which UK health policy was compartmentalised and took insufficient account of clustering between health behaviours.[11]

In 2012, a King’s Fund report described clustering of unhealthy behaviours (smoking, heavy alcohol use, poor diet, and low levels of physical activity) in the English population and noted that these behaviours do not arise independently of each other or of social circumstances.[11] The report estimated that 25% of the English adult population engaged in three or four poor health behaviours and that this pattern of behaviour was less prevalent among women, people of higher socioeconomic position, and older people; nonetheless, the report estimated that 20% of men and 15% of women aged 65 years and older engaged in three or more poor health behaviours. Given that health behaviours are potentially modifiable, and that hospitalisation is common among older people, this raises the possibility that interventions aimed at reducing the number of poor health behaviours that people engage in throughout the lifecourse could have a substantial impact on not only individual health outcomes in later life but also the burden placed on the NHS by an ageing population.

The King’s Fund report identified a lack of research evidence on the impact of combined health behaviours on morbidity and mortality; the report detailed only one UK study based on 20,244 men and women aged 45-79 years who participated in the EPIC-Norfolk study and among whom the presence of four poor health behaviours was associated with a four-fold increase in total mortality over an 11 year follow-up.[12] The King’s Fund report noted that longitudinal surveys linked with NHS administrative data have a valuable opportunity to investigate whether the presence of multiple poor health behaviours is related to morbidity.

In response to the King’s Fund report we have taken the opportunity to explore the association between number of poor health behaviours (smoking, heavy alcohol use, poor diet, and low levels of physical activity) and risk of hospitalisation among the cohort of 2,997 community-dwelling men and women who participated in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS) between 1998-2004, when they were 59-73 years of age, and who have subsequently been followed-up for hospital admissions over a ten year period by linkage with routine Hospital Episode Statistics data.[13]

METHODS

Literature review

We used OVID to search the databases MEDLINE (including in-process citations) and EMBASE for English language publications (from 1980 up to April 2015) which described studies that had used linkage with routinely collected NHS data to explore the longitudinal association between poor health behaviours and risk of hospital admission among community-dwelling older people in the UK. We used a combination of MESH subject headings and free-text terms to specify our search criteria. MESH headings comprised: “health behaviour”, “life style”, “hospitalization”, “aged”, “cohort studies”, “follow-up studies”, “prospective studies”, “registries” and “Great Britain”. Free-text search terms included: “smoking”, “smoker”, “alcohol”, “heavy drinking”, “physical activity”, “sedentary”, “diet”, “NHS”, “hospital episode statistics”, “inpatient”, “older adults”, “record linkage”. We screened the titles of 2002 articles for relevance, excluding studies which focussed only on groups of older people with specific morbidities such as diabetes or renal failure, or which examined risk factors for readmission to hospital. We subsequently reviewed 63 abstracts and retrieved the full text of 19 relevant publications.

The Hertfordshire Cohort Study (HCS)

The HCS comprises 1579 men and 1418 women born in the English county of Hertfordshire between 1931 and 1939 and who still lived there in 1998 to 2004 when they completed a home interview and research clinic for detailed characterisation of their health behaviours and socio-demographic and clinical characteristics; the study has been described in detail previously.[14] Smoking status (never/ex/current), weekly consumption of alcohol (in units), and customary level of physical activity (Dallosso questionnaire[15]) were ascertained by a nurse-administered questionnaire. Participants completed a food-frequency questionnaire from which a ‘prudent diet’ score was derived using principal components analysis; high scores reflect healthier diets: high in consumption of fruit, vegetables, whole-grain cereals, and oily fish but low in consumption of white bread, chips, sugar, and full-fat dairy products.[16] Details of all prescription and over-the-counter medications taken were coded according to the British National Formulary; the number of systems medicated was used as a marker of co-morbidity. The study had ethical approval and participants gave signed consent to participate in the study and for their health records to be accessed in the future. Investigations on participants were conducted in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. The cohort is flagged on the NHS Central Register for continuous notification of deaths.

As described previously, an extract of routinely collected Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) data[17] detailing hospital admissions between 1st April 1998 to 31st March 2010 was obtained for linkage with HCS[13]; records relating to the same individual were brought together to create a personal admissions history alongside details of death where appropriate. Admissions occurring before the baseline HCS clinic were excluded; thus histories comprised information on all hospital admissions between the date of attendance at HCS baseline clinic and 31st March 2010.

Statistical methods

In keeping with previous HCS analyses,[18] we coded four binary variables representing poor health behaviours: current smoking; weekly consumption of alcohol in excess of recommended ‘lower-risk guidelines’ (>21 units for men, >14 for women)[10]; low customary physical activity (Dallosso physical activity score <50); and poor diet (prudent diet score in the bottom quarter of the HCS distribution). These variables were summed to yield a score ranging from zero to four which reflects an increasing number of poor health behaviours.

Binary variables were coded to classify each hospital admission as: elective (day case); elective (overnight or longer); emergency; long-stay (exceeding seven days). We also coded whether participants ever experienced a 30-day, or emergency 30-day, readmission during the follow-up period. As defined, these hospital-related outcomes approximate an increasing burden to the NHS by cost, complexity and unpredictability.[19]

Data were described using means and standard deviations (SD), medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQR) and frequency and percentage distributions. Inter-relationships between the four health behaviours were identified by a Poisson regression analysis of the underlying 4×4 contingency table. Associations between the health behaviour score and risk of each type of hospital outcome were analysed using the Prentice, Williams and Peterson Total Time (PWP-TT) multiple-failure survival analysis model with death considered as an alternative failure event in all instances. The PWP-TT model allows the association between the health behaviour score and the risk of hospital outcomes to be examined whilst taking into account admissions that occur after an individual’s first and incorporating the fact that times to events are likely to be correlated in the same individual. In addition, the PWP-TT model allows an individual’s risk of admission to increase with the number of admissions previously accrued; an appropriate assumption for a study of risk factors for hospitalisation among older people. Associations between number of poor health behaviours and 30-day readmission (any, or emergency) were analysed using Poisson regression with a robust variance estimator. Analyses were carried out as follows: unadjusted; adjusted for age; and adjusted for age, BMI and number of systems medicated at HCS baseline.

Men and women were analysed separately throughout using the Stata statistical software package, release 13.

RESULTS

Literature review

We identified 19 articles that described the longitudinal association between poor health behaviours and risk of hospital admission (identified by linkage with routinely collected NHS data) among community-dwelling older people in the UK. Eleven utilised the Scottish Paisley-Renfrew[20-24] or Scottish Health Survey studies[25-30] which ascertain hospital admissions by linkage with health records. Seven articles were based on English studies linked with Hospital Episode Statistics data (i.e. the Million Women[31-34], EPIC-Oxford,[35] QAdmissions,[36] and UK Women’s Cohort[37] studies). One small study extracted admissions information directly from medical records.[38] All these studies collected information on several health behaviours but focussed on only one as the principal risk factor for hospitalisation: smoking, alcohol use, poor diet and low physical activity were of principal interest in seven,[20-23 25 34 36] three,[24 26 28] two,[35 37] and three[29 31 38] of the articles respectively and were generally shown to be associated with greater risk of hospitalisation. Four articles were principally focussed on body mass index as a risk factor for hospital admission and only considered poor health behaviours as adjustment factors.[27 30 32 33] None of the articles described the longitudinal association between number of poor health behaviours and risk of hospital admission.

Analysis of the HCS database

HCS participants are described in Table 1; their average age was 66 years at baseline. In total, 75% of men and 69% of women were admitted to hospital at least once during the follow-up period; the median number of admissions among those ever admitted was 3 (IQR 1-6) for men and 2 (IQR 1-5) for women. 189 men and 86 women died during follow-up; all but 12 men and 9 women had also experienced a hospital admission.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

| n(%) | Men (n=1579) | Women (n=1418) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs)+ | 65.7 (2.9) | 66.6 (2.7) |

| Height (cm)+ | 174.2 (6.5) | 160.8 (5.9) |

| Weight (kg)+ | 82.4 (12.7) | 71.4 (13.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2)+ | 27.2 (3.8) | 27.6 (4.9) |

| High BMI (≥30kg/m2) | 316 (20.1) | 395 (27.9) |

| Number of systems medicated* | 1 (0,2) | 1 (1,2) |

| Ever any admission | 1185 (75.0) | 976 (68.8) |

| Ever any admission / died | 1197 (75.8) | 985 (69.5) |

| Ever day-elective admission | 912 (57.8) | 750 (52.9) |

| Ever day-elective admission / died | 983 (62.3) | 788 (55.6) |

| Ever overnight-elective admission | 573 (36.3) | 461 (32.5) |

| Ever overnight-elective admission / died | 676 (42.8) | 511 (36.0) |

| Ever emergency admission | 608 (38.5) | 433 (30.5) |

| Ever emergency admission / died | 638 (40.4) | 450 (31.7) |

| Ever long stay (>7 day) admission | 429 (27.2) | 316 (22.3) |

| Ever long stay (>7 day) admission / died | 486 (30.8) | 340 (24.0) |

| Ever readmission (<30 days) | 371 (23.5) | 244 (17.2) |

| Ever readmission (<30 days) / died | 458 (29.0) | 288 (20.3) |

| Ever emergency readmission (<30 days) | 201 (12.7) | 126 (8.9) |

| Ever emergency readmission (<30 days) / died | 313 (19.8) | 180 (12.7) |

| Deaths | 189 (12.0) | 86 (6.1) |

| Physical activity score+ | 60.9 (15.3) | 59.0 (15.7) |

| Low physical activity score | 467 (29.6) | 487 (34.3) |

| Prudent diet score+ | −0.6 (2.1) | 0.7 (1.7) |

| Low prudent diet score | 580 (36.8) | 169 (11.9) |

| High alcohol consumption | 340 (21.6) | 68 (4.8) |

| Current smoker | 238 (15.1) | 139 (9.8) |

| Number of poor health behaviours: 0 | 512 (32.5) | 724 (51.1) |

| 1 | 634 (40.2) | 545 (38.4) |

| 2 | 319 (20.2) | 125 (8.8) |

| 3 | 97 (6.2) | 20 (1.4) |

| 4 | 15 (0.9) | 2 (0.1) |

Mean(SD)

Median (Lower quartile, Upper quartile)

SD: standard deviation

Low physical activity was defined as a Dallosso score ≤50. Poor diet was defined as a low prudent diet score was defined as a score in the bottom quarter of the distribution.

High alcohol consumption defined as >21 units per week for men and >14 units per week for women.

Men were more likely than women to: be current smokers; report high weekly alcohol consumption; and have a less healthy diet (as indicated by lower prudent diet scores). Self-reported levels of customary physical activity were similar for men and women. 32% of men and 51% of women did not engage in any poor health behaviours; 7% of men and 2% of women engaged in three or four. The distribution of combinations of poor health behaviours according to the health behaviour score is shown in Table 2. A contingency table analysis identified the following dominant inter-relationships between the health behaviours: current smoking was associated with high alcohol consumption, independent of diet quality; current smoking was associated with having a poor diet, independent of level of alcohol consumption; and having a poor diet was associated with high alcohol consumption, independent of smoking status.

Table 2. Distribution of poor health behaviours according to health behaviour score.

| Health behaviour score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution of poor health behaviours | 1 | 2 | 3 or 4 | |||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Activity | 208 (32.8%) | 373 (68.4%) | ||||

| Diet | 248 (39.1%) | 73 (13.4%) | ||||

| Alcohol | 127 (20.0%) | 36 (6.6%) | ||||

| Smoking | 51 (8.0%) | 63 (11.6%) | ||||

| Total | 634 | 545 | ||||

| Activity-Diet | 97 (30.4%) | 51 (40.8%) | ||||

| Activity-Alcohol | 62 (19.4%) | 13 (10.4%) | ||||

| Activity-Smoking | 17 (5.3%) | 31 (24.8%) | ||||

| Diet-Alcohol | 59 (18.5%) | 3 (2.4%) | ||||

| Diet-Smoking | 68 (21.3%) | 23 (18.4%) | ||||

| Alcohol-Smoking | 16 (5.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | ||||

| Total | 319 | 125 | ||||

| Activity-Diet-Alcohol | 27 (24.1%) | 4 (18.2%) | ||||

| Activity-Diet-Smoking | 36 (32.1%) | 10 (45.5%) | ||||

| Diet-Alcohol-Smoking | 29 (25.9%) | 3 (13.6%) | ||||

| Activity-Alcohol-Smoking | 5 (4.5%) | 3 (13.6%) | ||||

| Activity-Alcohol-Diet-Smoking | 15 (13.4%) | 2 (9.1%) | ||||

| Total | 112 | 22 | ||||

Percentages are relative to the total number of men or women with the health behaviour score indicated

The associations between number of poor health behaviours and risk of each type of hospital admission among HCS men and women are shown in Table 3. Increased number of poor health behaviours was significantly (p<0.01) associated with greater risk of all types of admissions among women. Results were similar for men although number of poor health behaviours was not associated (p>0.05) with risk of overnight or longer elective admission, or with ‘any 30 day readmission’. These results were little altered by adjustment for age, body mass index, and number of systems medicated as a marker of co-morbidity (Table 3).

Table 3. Associations between number of poor health behaviours and risk of admission outcomes among Hertfordshire Cohort Study participants.

| Association between number of poor health behaviours and the risk of each outcome* |

Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Any admission/death | Unadj | 1.05 (1.01,1.09) | 0.013 | 1.11 (1.05,1.16) | <0.001 |

| Adj | 1.05 (1.01,1.09) | 0.010 | 1.10 (1.05,1.16) | <0.001 | |

| Day elective admission/death | Unadj | 1.05 (1.00,1.09) | 0.043 | 1.11 (1.04,1.18) | 0.002 |

| Adj | 1.05 (1.00,1.09) | 0.029 | 1.10 (1.04,1.18) | 0.002 | |

| Overnight elective admission/death | Unadj | 1.06 (0.99,1.13) | 0.074 | 1.17 (1.07,1.29) | 0.001 |

| Adj | 1.06 (1.00,1.13) | 0.056 | 1.17 (1.07,1.28) | 0.001 | |

| Any emergency admission/death | Unadj | 1.13 (1.06,1.20) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.14,1.37) | <0.001 |

| Adj | 1.13 (1.06,1.20) | <0.001 | 1.25 (1.14,1.37) | <0.001 | |

| Any admission lasting longer than 7 days/death | Unadj | 1.13 (1.05,1.22) | 0.001 | 1.31 (1.18,1.46) | <0.001 |

| Adj | 1.14 (1.05,1.22) | 0.001 | 1.32 (1.18,1.46) | <0.001 | |

| Any readmission within 30 days/death** | Unadj | 1.07 (0.99,1.16) | 0.094 | 1.30 (1.14,1.47) | <0.001 |

| Adj | 1.08 (0.99,1.17) | 0.074 | 1.30 (1.14,1.47) | <0.001 | |

| Emergency readmission within 30 days/death** | Unadj | 1.16 (1.05,1.28) | 0.004 | 1.40 (1.20,1.63) | <0.001 |

| Adj | 1.17 (1.05,1.29) | 0.003 | 1.40 (1.20,1.64) | <0.001 | |

Poor health behaviours: low physical activity (activity score ≤50), poor diet (prudent diet score in bottom quarter of distribution), high alcohol consumption (men: >21 units per week, women: >14 units per week), current smoker.

Estimates of association are hazard ratios (95% CI) from PWP-TT models, corresponding to the risk of each hospital related outcome per unit increase in the number of poor health behaviours.

Estimates of association are relative risks (95% CI) from Poisson regression models, corresponding to the risk of each hospital related outcome per unit increase in the number of poor health behaviours.

Unadj: unadjusted model; Adj: adjusted for age

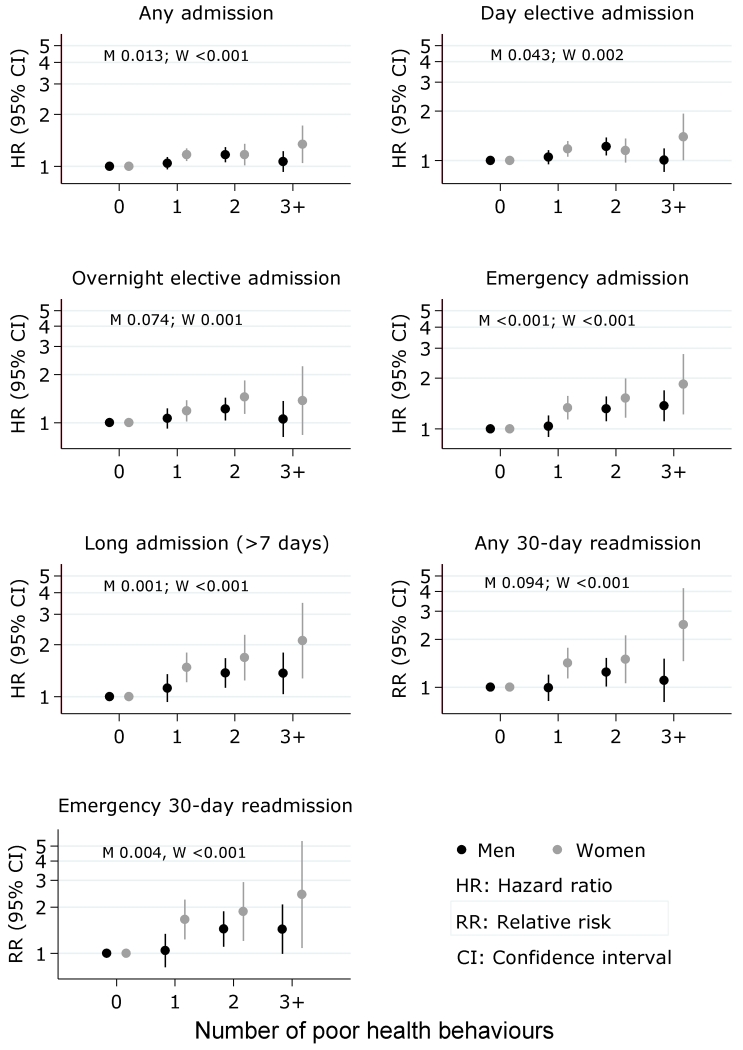

Figure 1 presents relative risks for hospital admission according to number of poor health behaviours in comparison with a reference category of ‘no poor health behaviours’. Progressively increased relative risks for various types of hospital admission are apparent in relation to a higher number of poor health behaviours, particularly for more complex types of admission such as long stays (>7 days), emergency admissions, and 30-day emergency readmissions. For example, unadjusted hazard ratios for emergency admission among women were: one poor health behaviour vs none 1.33[95%CI:1.14,1.57], two vs none 1.52[95%CI:1.16,1.99], three or four vs none 1.84[95%CI:1.22,2.77]. Corresponding estimates for men were: 1.04[95%CI:0.90,1.20], 1.31[95%CI:1.11,1.56], and 1.37[95%CI:1.11,1.69].

Figure 1. Unadjusted associations between number of poor health behaviours and risk of admission outcomes among men and women.

Poor health behaviours: low physical activity (activity score ≤50), poor diet (prudent diet score in bottom quarter of distribution), high alcohol consumption (men: >21 units per week, women: >14 units per week), current smoker.

Number of poor health behaviours was coded as 0, 1, 2 and 3 or more.

The horizontal axis of all sub-plots shows the number of poor health behaviours

P-values were calculated for men (M) and women (W) using an ordinal variable to represent number of poor health behaviours (1, 2, 3 and 4).

Death was included as an alternative failure event in all instances.

Using relative risks from this study, and population prevalence estimates for number of poor health behaviours from the King’s Fund[11], the data suggest that if people aged 65 and older who engage in two or more poor health behaviours were to engage in fewer than two, this would be associated with 18% and 21% reductions in number of emergency admissions among men and women respectively.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that clustered poor health behaviours are associated with increased risk of hospital admission among community-dwelling older people, independently of age, body mass index and co-morbidity. Among men and women, greater number of poor health behaviours was associated with increased risk of complex types of admission such as long stays (>7 days), emergency admissions, and 30-day emergency readmissions.

Our findings have several important implications. First, they identify the role of clustered poor health behaviours as a risk factor for hospital admission among older people; this knowledge could provide focus for strategies to promote health among older people and to reduce the risk of hospitalisation in later life. Second, our results support recent calls for the Department of Health to adopt a fully integrated and holistic approach to behaviour change with the aim of improving population health and reducing social inequalities in health.[11] Finally, our results suggest that the development of lifecourse interventions to reduce the number of poor health behaviours that people engage in could have a substantial beneficial impact on individual health outcomes and use of healthcare in later life.

Our literature review did not identify any previous studies with which we may directly compare our results. However, our work builds on a 2012 King’s Fund report which analysed data from the Health Survey for England and showed that poor health behaviours cluster and arise with greater frequency among disadvantaged subgroups of the population; the report did not relate number of poor health behaviours to health and healthcare outcomes.[11] Our results are broadly consistent with work by Khaw[12] and Kvaavik[39] who have demonstrated increased risk of mortality in relation to a greater number of poor health behaviours using data from the EPIC-Norfolk study and the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey respectively.

For consistency with the King’s Fund, Khaw, and Kvaavik we defined a “poor health behaviour score” on the basis of smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, low physical activity and poor diet. We did not include BMI in our score, preferring to regard BMI as an attribute that arises at least in part as a consequence of these poor health behaviours.[40] High BMI is of course a risk factor for ill health[5 6] and is likely to mediate some of the impact of poor health behaviours on increased risk of hospitalisation. However, our results were robust to adjustment for BMI which suggests that poor health behaviours exert an influence on risk of hospitalisation through pathways other than elevated BMI. For example, poor health behaviours co-occur most frequently among people of low socioeconomic position[11]; indeed, the prevalence of two or more poor health behaviours among HCS men of manual social class was 31% in contrast with 22% among men of non-manual social class (corresponding prevalences for women: 12% versus 8%). The increased risks of hospitalisation identified in this study in relation to a high number of poor health behaviours, even after adjustment for BMI, may be a reflection of accumulated lifecourse socioeconomic disadvantage e.g. low education, low income, poor housing and psychosocial stressors. Further work that explores the combined pathways through which socioeconomic position, health behaviours, and BMI exert their influence on risk of hospitalisation is required.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, a healthy responder bias has unsurprisingly been identified in HCS[14] and the study is located in the relatively affluent area of South East England. However, the characteristics of HCS participants have been shown to be broadly comparable with those of participants in the nationally representative Health Survey for England[14] and our analyses were internal; unless the association between poor health behaviours and risk of hospitalisation is systematically different among sub-groups of the population, no major bias should have been introduced. Second, doubts have been expressed over the validity of Hospital Episode Statistics; however, case ascertainment through HES has been compared with that of a number of disease-specific registries and in general, HES has been found to be the more complete.[13] Third, we were only able to characterise customary physical activity using the Dallosso questionnaire; a more comprehensive assessment of physical activity would have been desirable but such data are not available in HCS. Finally, we created binary variables representing poor health behaviours, a pragmatic approach which admittedly discards the full breadth of information contained in ordinal and continuous variables. However, our approach was consistent with previous work in this field[11 12 18 39] and our choice of categorisations may be justified as follows. We focussed on current rather than ever smoking because current smoking remains amenable to modification; moreover, ex-smokers in HCS are a heterogeneous group ranging from people who only smoked briefly when young, to those who smoked heavily for years. Our dichotomisation of weekly alcohol consumption was based on ‘lower-risk guidelines’ for England.[10] In the absence of reference data for the Dallosso physical activity and prudent diet scores, we categorised these variables in the same way as Robinson.[18]

Strengths

Our study also has many strengths. First, our analyses are based on prospective, routinely collected hospital admissions data; the HCS is one of only a few English cohort studies that have enriched their detailed research databases by data linkage with Hospital Episode Statistics. Linkage with HES has provided almost attrition-proof follow-up for the whole HCS cohort. Second, the HCS database provides a detailed characterisation of community-dwelling older men and women in England; measurements were carried out according to strict protocols by trained fieldworkers. The database is managed by an experienced multidisciplinary team with meticulous levels of data entry, record keeping and statistical analysis. The recently added HES data have been scrutinised and prepared to the same standards.[13] Finally, we conducted a thorough review of the most appropriate statistical analysis techniques for the linked HCS/HES dataset. After comparison of a number of survival analysis modelling techniques (time-to-first event Cox modelling; Andersen and Gill and Prentice, Williams and Peterson Total Time (PWP-TT) multiple failure models) which differed in their ability to include repeated hospitalisations and account for an individual’s previous number of admissions when assessing risk of admission, the PWP-TT model was chosen for this analysis.[41]

In conclusion, we have shown that clustered poor health behaviours are strongly associated with increased risk of emergency and long stay hospital admissions as well as 30-day readmissions among community-dwelling older people in England, independently of body mass index and co-morbidity. Lifecourse interventions designed to reduce the number of poor health behaviours that people engage in could have substantial beneficial impact on health and use of healthcare in later life.

What is already known on this subject?

Rates of hospital admission are increasing, particularly among older people. Improved understanding of the patterns and risk factors for hospitalisation is required.

Smoking, excessive alcohol use, low levels of physical activity and poor diet are risk factors for ill health and premature mortality; these poor health behaviours typically cluster.

No UK studies have examined number of poor health behaviours as a risk factor for hospital admission among older people; we addressed this using the Hertfordshire Cohort Study linked with Hospital Episode Statistics data.

What this study adds?

Among community-dwelling older men and women, increased number of poor health behaviours is strongly associated with greater risk of long stay and emergency hospital admission, and 30-day emergency readmission, independently of age, body mass index and co-morbidity.

Interventions to reduce the number of poor health behaviours that people engage in could have a substantial impact on individual health outcomes in later life and also on the burden placed on the NHS by an ageing population.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council [MC_UP_A620_1015, MC_UU_12011/2] and University of Southampton UK.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

None declared.

References

- 1.Smith P, McKeon A, Blunt I, et al. [accessed 30/06/2015];NHS Hospitals under pressure: trends in acute activity up to 2022. 2014 http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/files/nuffield/publication/ft_hospitals_analysis.pdf.

- 2.Office for National Statistics [accessed 8th April 2015];2013 Annual Mid-year Population Estimates. 2014 http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_367167.pdf.

- 3.Cornwell J, Levenson R, Sonola L, et al. [accessed 3rd June 2015];Continuity of care for older hospital patients: a call for action. 2012 http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/continuity-of-care-for-older-hospital-patients-mar-2012.pdf.

- 4.Office for National Statistics [accessed 8th April 2015];Population ageing in the United Kingdom its constituent countries and the European Union. 2012 http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_258607.pdf.

- 5.World Health Organisation [accessed 10th June 2015];The World Health Report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. 2002 http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/whr02_en.pdf?ua=1.

- 6.Murray CJ, Richards MA, Newton JN, et al. UK health performance: findings of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381(9871):997–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzuto D, Orsini N, Qiu C. Lifestyle, social factors, and survival after age 75: population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5568. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health England [accessed 8th April 2015];From evidence into action: opportunities to protect and improve the nation’s health. 2014 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/from-evidence-into-action-opportunities-to-protect-and-improve-the-nations-health.

- 9.NHS Future Forum [accessed 8th April 2015];The NHS’s role in the public’s health: a report from the NHS Future Forum. 2012 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216423/dh_132114.pdf.

- 10.National Health Service [accessed 8th April 2015];Change4Life: eat well, move more, live longer. 2015 http://www.nhs.uk/change4life/Pages/change-for-life.aspx.

- 11.Buck D, Frosini F. [accessed 8th April 2015];Clustering of unhealthy behaviours over time: implications for policy and practice. 2012 http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/clustering-of-unhealthy-behaviours-over-time-aug-2012.pdf.

- 12.Khaw KT, Wareham N, Bingham S, et al. Combined impact of health behaviours and mortality in men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmonds SJ, Syddall HE, Walsh B, et al. Understanding NHS hospital admissions in England: linkage of Hospital Episode Statistics to the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing. 2014;43(5):653–60. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Syddall HE, Aihie SA, Dennison EM, et al. Cohort profile: the Hertfordshire cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34(6):1234–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dallosso HM, Morgan K, Bassey EJ, et al. Levels of customary physical activity among the old and the very old living at home. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1988;42(2):121–27. doi: 10.1136/jech.42.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson S, Syddall H, Jameson K, et al. Current patterns of diet in community-dwelling older men and women: results from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Age Ageing. 2009;38(5):594–99. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health and Social Care Information Centre [accessed 8th April 2015];Hospital Episode Statistics. Secondary Hospital Episode Statistics. 2015 http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hes.

- 18.Robinson SM, Jameson KA, Syddall HE, et al. Clustering of lifestyle risk factors and poor physical function in older adults: the Hertfordshire cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1684–91. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Department of Health [accessed 8th April 2015];Reference Costs 2011-12. 2012 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-financial-year-2011-to-2012.

- 20.Hanlon P, Walsh D, Whyte BW, et al. Influence of biological, behavioural, health service and social risk factors on the trend towards more frequent. Health bulletin. 2000;58(4):342–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanlon P, Walsh D, Whyte BW, et al. Hospital use by an ageing cohort: An investigation into the association between biological, behavioural and social risk markers and subsequent hospital utilization. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 1998;20(4):467–76. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanlon P, Walsh D, Whyte BW, et al. The link between major risk factors and important categories of admission in an ageing cohort. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2000;22(1):81–89. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/22.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart CL, Hole DJ, Smith GD. Comparison of risk factors for stroke incidence and stroke mortality in 20 years of follow-up in men and women in the Renfrew/Paisley study in Scotland. Stroke. 2000;31(8):1893–96. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hart CL, Smith GD. Alcohol consumption and mortality and hospital admissions in men from the Midspan collaborative cohort study. Addiction. 2008;103(12):1979–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanlon P, Lawder R, Elders A, et al. An analysis of the link between behavioural, biological and social risk factors and subsequent hospital admission in Scotland. Journal of Public Health. 2007;29(4):405–12. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdm062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hart CL, Davey Smith G. Alcohol consumption and use of acute and mental health hospital services in the West of Scotland Collaborative prospective cohort study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2009;63(9):703–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.079764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hotchkiss JW, Davies CA, Leyland AH. Adiposity has differing associations with incident coronary heart disease and mortality in the Scottish population: cross-sectional surveys with follow-up. International journal of obesity. 2013;37(5):732–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald SA, Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, et al. Association of self-reported alcohol use and hospitalization for an alcohol-related cause in Scotland: a record-linkage study of 23,183 individuals. Addiction. 2009;104(4):593–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Lawlor DA. Physical activity, mortality, and cardiovascular disease: Is domestic physical activity beneficial? American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169(10):1191–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wulff J, Wild SH. The relationship between body mass index and number of days spent in hospital in Scotland. Scottish Medical Journal. 2011;56(3):135–40. doi: 10.1258/smj.2011.011110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong M, B JC, Green J, et al. Association between reported baseline physical activity and hospital admission for Venus thromboembolism in a prospective cohort study. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;1:S23–S24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroll M, Reeves G, Green J, et al. Body mass index in relation to incidence of stroke subtypes among UK women: Cohort study. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;1:S25. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reeves GK, Balkwill A, Cairns BJ, et al. Hospital admissions in relation to body mass index in UK women: A prospective cohort study. BMC medicine. 2014;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spencer EA, Pirie KL, Stevens RJ, et al. Diabetes and modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease: The prospective Million Women Study. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;23(12):793–99. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crowe FL, Appleby PN, Travis RC, et al. Risk of hospitalization or death from ischemic heart disease among British vegetarians and nonvegetarians: results from the EPIC-Oxford cohort study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013;97(3):597–603. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.044073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Predicting risk of emergency admission to hospital using primary care data: Derivation and validation of QAdmissions score. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Threapleton D, Burley V, Greenwood D, et al. Dietary fibre and risk of haemorrhagic or ischaemic stroke in the UK Women’s Cohort Study. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2013;1:S25. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simmonds B, Fox K, Davis M, et al. Objectively assessed physical activity and subsequent health service use of UK adults aged 70 and over: A four to five year follow up study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kvaavik E, Batty GD, Ursin G, et al. Influence of individual and combined health behaviors on total and cause-specific mortality in men and women: the United Kingdom health and lifestyle survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(8):711–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borodulin K, Zimmer C, Sippola R, et al. Health behaviours as mediating pathways between socioeconomic position and body mass index. International journal of behavioral medicine. 2012;19(1):14–22. doi: 10.1007/s12529-010-9138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Westbury L. Identification of risk factors for hospital admission using multiple-failure survival models: a toolkit for researchers; Oral presentation at the Royal Statistical Society Special Conference on Statistical Challenges in Lifecourse Research; University of Leeds. 19th March 2015; http://www.personal.leeds.ac.uk/~stapdb/lifecourse2015/abstracts/westbury.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]