Abstract

Sexual differentiation in teleost fishes is characteristically labile. The most dramatic form of sexual lability is postmaturational sex change, which is common among teleosts although rare or absent in other vertebrate taxa. In many cases this process is regulated by social cues, particularly dominance interactions. Here we show that in the Midas cichlid, Cichlasoma citrinellum, these same sorts of social interactions affect much earlier stages of sexual differentiation. In this species, males are larger than females. By manipulating relative size in juveniles, we show that this sex-based size difference does not arise from endogenous factors associated with sex. Rather, sex is determined by relative size as a juvenile. We argue that this mode of sex determination, which may be common among teleosts, is a heterochronic variant of postmaturational sex change, one in which some individuals are deflected from a default female trajectory before maturation, as a result of social signals. The size-advantage model, which specifies the optimal size for sex change in hermaphroditic species, can be extended to account for the decision whether to mature as a male or a female in the Midas cichlid.

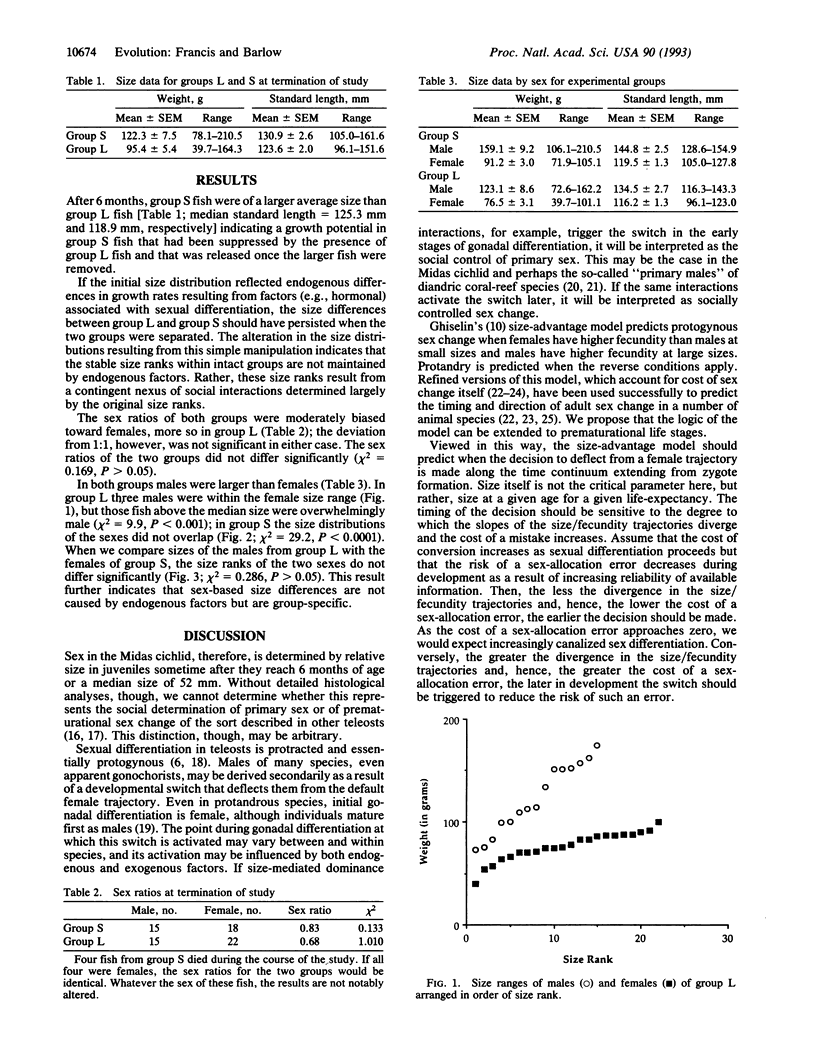

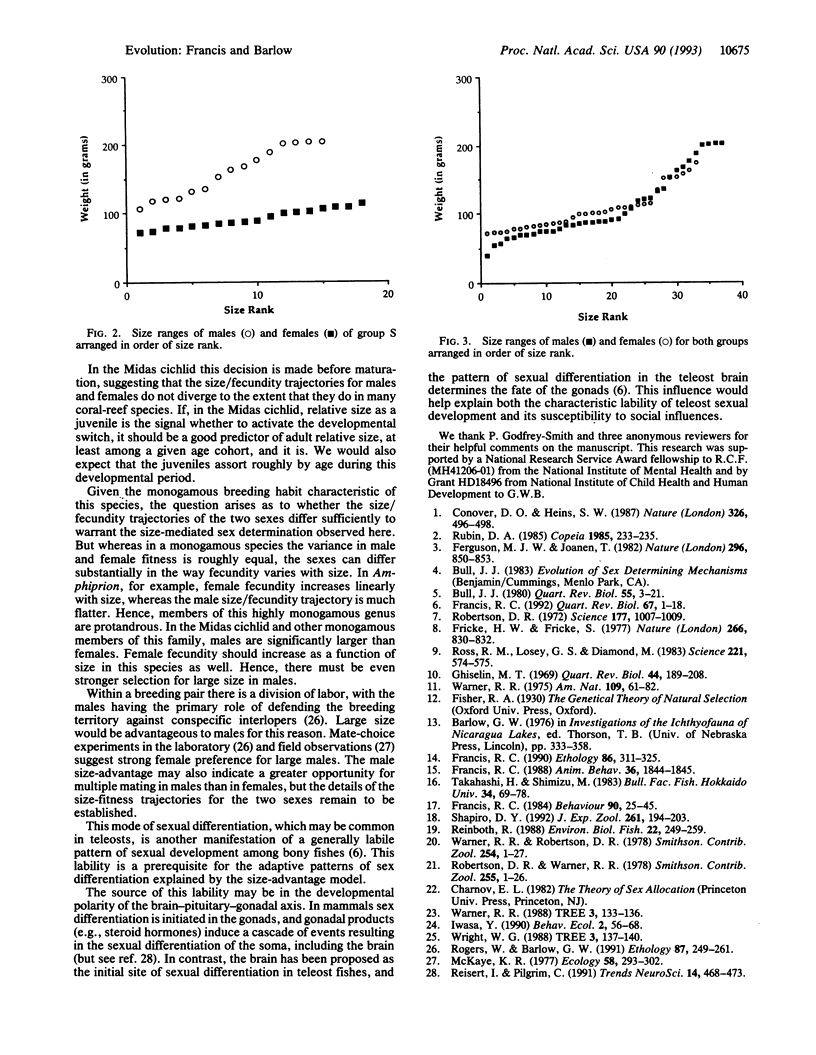

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Conover D. O., Heins S. W. Adaptive variation in environmental and genetic sex determination in a fish. Nature. 1987 Apr 2;326(6112):496–498. doi: 10.1038/326496a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M. W., Joanen T. Temperature of egg incubation determines sex in Alligator mississippiensis. Nature. 1982 Apr 29;296(5860):850–853. doi: 10.1038/296850a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke H., Fricke S. Monogamy and sex change by aggressive dominance in coral reef fish. Nature. 1977 Apr 28;266(5605):830–832. doi: 10.1038/266830a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiselin M. T. The evolution of hermaphroditism among animals. Q Rev Biol. 1969 Jun;44(2):189–208. doi: 10.1086/406066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisert I., Pilgrim C. Sexual differentiation of monoaminergic neurons--genetic or epigenetic? Trends Neurosci. 1991 Oct;14(10):468–473. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R. M., Losey G. S., Diamond M. Sex change in a coral-reef fish: dependence of stimulation and inhibition on relative size. Science. 1983 Aug 5;221(4610):574–575. doi: 10.1126/science.221.4610.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D. Y. Plasticity of gonadal development and protandry in fishes. J Exp Zool. 1992 Feb 1;261(2):194–203. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402610210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]