Abstract

Background:

The term molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH) has been described as a clinical entity of systemic origin affecting the enamel of one or all first permanent molars and also the incisors; less frequently the second primary molars have also been reported to develop hypomineralization of the enamel, along with MIH.

Aim:

To scrutinize the association between hypomineralized second primary molars (HSPMs) and MIH and their prevalence in schoolgoing pupils in Nagpur, Maharashtra, India and the associated severity of dental caries.

Design:

A sample of 1,109 pupils belonging to 3–12-year-old age group was included. The entire sample was then divided into Group I (3–5 years) and Group II (6–12 years). The scoring criteria proposed by the European Academy of Pediatric Dentistry for hypomineralization was used to score HSPM and MIH. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System II (ICDAS II) was used for appraising caries status in the hypomineralized molars. The examination was conducted by a single calibrated dentist in schools in daylight. The results, thus obtained, were statistically analyzed using Chi-square test and odds ratio.

Result:

Of the children examined, 10 in Group I (4.88%) had HSPM and 63 in Group II (7.11%) had MIH in at least one molar. In Group II, out of 63 subjects diagnosed with MIH, 30 subjects (48%) also had HSPM. Carious lesions with high severity were appreciated in hypomineralized molars.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of HSPM was 4.88% and of MIH was 7.11%. Approximately half of the affected first permanent molars were associated with HSPM. The likelihood of development of caries increased with the severity of hypomineralization defect.

Keywords: Dental caries, hypomineralized second primary molar, molar incisor hypomineralization

INTRODUCTION

Developmental disturbances of the tooth enamel are common in both sets of dentition and broadly divided as hypomineralization and hypoplasia.[1,2]

The term molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH) has been described as a clinical entity of systemic origin affecting the enamel of one or all first permanent molars and also the incisors; less frequently, the second primary molars have also been reported to develop hypomineralization of the enamel, along with MIH.[3,4] Various studies in relation to the prevalence of MIH had been conducted round the globe, reporting its prevalence ranging 2.4–40.2%[5]

Investigations on second primary molars with hypomineralization are scarce. Elfrink et al.[6] were the first to report the prevalence of hypomineralized defects in second primary molars to be 4.9%. The literature had also reported the presence of an association between MIH and HSPM.[7,8]

Hypomineralization increases the chances of development of caries such as the advanced carious lesions masking the hypomineralized surfaces, resulting in underreporting of the prevalence of hypomineralization.[9]

Among the studies reported on the prevalence of hypomineralization, many had been conducted in the European continent and very few in the Asian subcontinent, especially India. Therefore, we aimed to scrutinize the association between hypomineralized second primary molars (HSPMs) and MIH and their prevalence in school going pupils in Nagpur, Maharashtra, India and associated severity of dental caries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was a cross-sectional survey conducted through a school-based dental health care program among the randomly selected pupils of public schools situated in the outskirts of Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. After obtaining ethical approval from the institutional committee and school jurisdiction, pupils with parental informed consent were included. Study samples were selected from 1,109 pupils with no medical and systemic illnesses belonging to the 3–12-year-old age group. Children who were absent on the day of the study and those who or whose parents declined consent were excluded. The sample thus obtained was segregated into Group I (3–5-year-old age group) and Group II (6–12-year-old age group). Group II exclusively included pupils with deciduous second molars and first permanent molars.

The first author was trained in diagnosing hypomineralized defects and caries using photographs from a previous study.[6] The intraexaminer consistency using kappa statistics for precisely detecting both hypomineralization as well as caries parameters was 88 and 100, respectively.

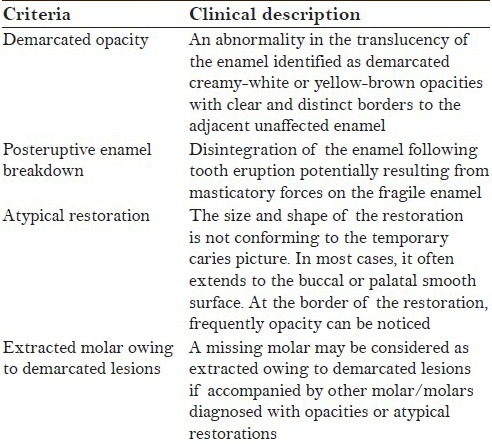

The study was conducted in public schools in natural daylight using mouth mirror (API, AshooSons, Delhi) and CPI probe (API, AshooSons, Delhi). European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (EAPD) criteria were used for the assessment of MIH and HSPM [Appendix 1].[4,6] All the surfaces (except the proximal surfaces) of the second primary molars, permanent incisors, and first permanent molars were examined for hypomineralization defects. In cases of uncertainty related to the lesion severity of hypomineralization defects, the less severe rating was considered. Also, a defect of less than 2 mm in diameter were recorded as sound.

Appendix 1.

Criteria for scoring hypomineralization defects (EAPD, 2003)

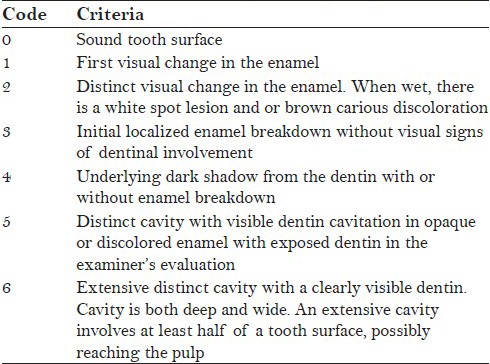

Caries in the molars was investigated using the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS II) scoring criteria [Appendix 2].[10] ICDAS II Code 1 was excluded due to unavailability of the usage of compressed air for drying the teeth. Cases exhibiting multiple carious lesions on the same surface were tackled by recording the most severe lesion. The obtained data were recorded in data sheets.

Appendix 2.

International Caries Detection and Assessment System II (2007)

Analysis

All the collected data were entered and computed by statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 17.0 for Windows. Chi-square test was used for assessing the relationship between the severity of hypomineralization defects and caries. Odds ratio was used for calculating the vulnerability for caries among hypomineralized and nonhypomineralized molars.

RESULTS

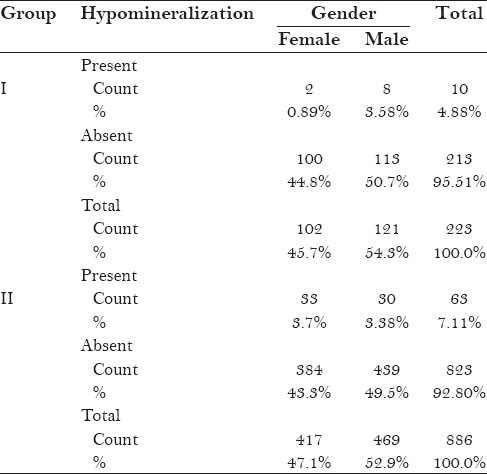

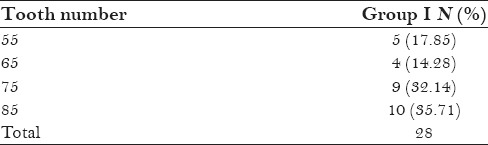

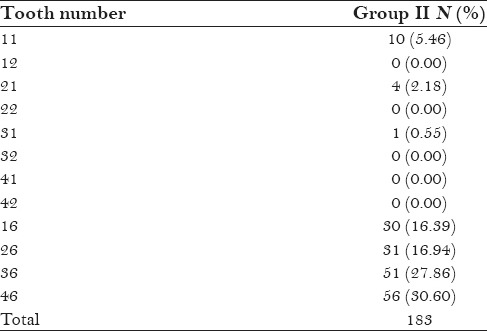

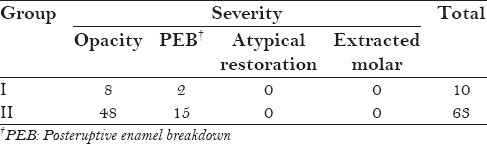

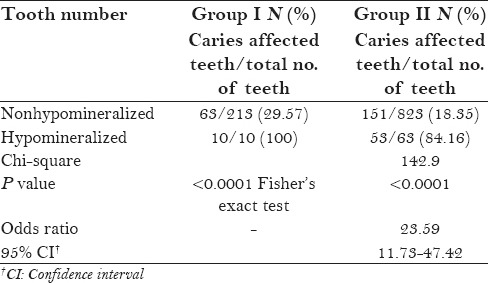

Distribution of subjects according to gender is illustrated in Table 1. In Group I, among the 223 subjects, 10 subjects had at least one HSPM, resulting in a prevalence rate of 4.88%. In Group II, 63 out of 886 subjects were diagnosed with at least one MIH resulting in a prevalence of 7.11%. Distribution of hypomineralized teeth according to tooth number is illustrated in Tables 2 and 3. A total of 28 teeth in Group I and 183 teeth in Group II were reported with hypomineralization defects. In Group I, the mandibular right second deciduous molar (35.71%) and in Group II, the mandibular right first permanent molar (30.60%) were the most frequently affected. In both the groups, the recurrent type of hypomineralized defect was demarcated opacities followed by posteruptive breakdown (PEB). None of the subjects were diagnosed with atypical restoration or extracted molars [Table 4]. In Group II, out of 63 subjects diagnosed with MIH, 30 subjects (48%) also had at least one HSPM. A significant positive association was appreciated between the severity of caries and hypomineralized lesions [Table 5].

Table 1.

Distribution of study groups according to gender

Table 2.

Distribution of hypomineralized teeth according to tooth number in Group I

Table 3.

Distribution of hypomineralized teeth according to tooth number in Group II

Table 4.

Distribution of hypomineralized teeth according to type of defect

Table 5.

Association between hypomineralization and caries

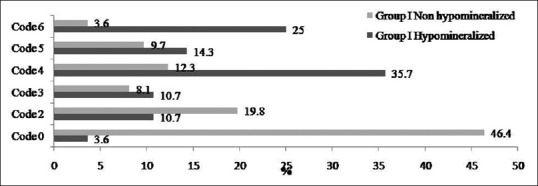

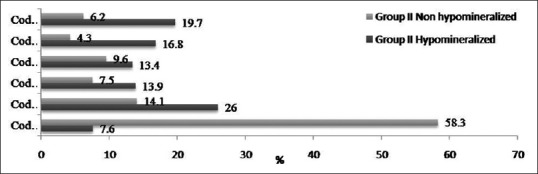

On comparing hypomineralized molars and nonhypomineralized molars by their dental caries status in both the groups, it was found that the possibility of occurrence of caries with higher severity was greater in hypomineralized molars compared to nonhypomineralized molars [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Distribution of hypomineralized and nonhypomineralized teeth by dental caries status diagnosed according to ICDAS II criteria in Group I

Figure 2.

Distribution of hypomineralized and nonhypomineralized teeth by dental caries status diagnosed according to ICDAS II criteria in Group II

DISCUSSION

Nonfluoride-related developmental anomalies of the enamel are recognized as alarming clinical dilemma. Enamel hypoplasia is a quantitative defect resulting due to disturbance to the enamel-forming cells during the stage of formation of matrix, whereas hypomineralization is a qualitative defect resulting due to disturbance occurring during the maturation stage of enamel formation.[4]

In the literature, various terminologies had been used to describe these demarcated enamel opacities and breakdowns such as internal enamel hypoplasia, cheese molars, nonendemic enamel mottling, idiopathic demarcated opacities, and nonfluoride hypomineralization. In 2001, Weerheijm termed it MIH because first permanent molars with hypomineralization are often related to affected permanent upper incisors and rarely lower incisors.[3] The presence of hypomineralization defects can considerably affect the child's overall well-being. Hypomineralized molars are more susceptible to plaque accumulation and dental caries.[11,12]

Various criteria had been used for the diagnosis of idiopathic enamel defects before the establishment of the EAPD criteria in 2003. These include the modified developmental defects of enamel (DDE) index proposed by federation dentaire internationale (FDI)[13] and used by Jalevik et al.[14] and Weerheijm et al.,[15] the one proposed by Alalausua et al.[16] and used by Leppaniemi et al.[11] According to the reports on MIH, the large variation in the prevalence and severity in the data appearing in the various studies worldwide were partly due to the different criteria used in the past for diagnosis of MIH. Therefore, in the current study, assessment of hypomineralization defects was performed using the criteria recommended by the EAPD in 2003.

In the present study, the prevalence of HSPM (Group I) was 4.88%. The studies that had used similar criteria reported a prevalence rate of 4.9% and 6.6% in the Netherlands[6] and Iraq,[7] respectively.

Prevalence of MIH in Group II was 7.11%, which was in line with other studies conducted in Gujarat (9.2%), Udaipur (9.46%), and Chandigarh (6.31%) in India as well as in Lithuania (9.7%) and Turkey (9.2%).[17,18,19,20,21] Prevalence rate of MIH varies throughout the globe with the rates ranging 2.4–40.2%.[5] Variations in the prevalence rate reflect the real differences between regions and countries, and differences in recording methods, indices used and populations investigated.[5,22,23]

In Group II, 30 subjects (n = 48%) out of 63 subjects reported with at least one HSPM, along with MIH indicating that HSPM could act as a predictor for MIH. A similar relationship was reported in studies conducted in Iraq and the Netherlands.[7,8]

Demarcated opacities were the most common form of hypomineralization defect, accounting for 80% in Group I and 76% in Group II. Second in the sequence was posteruptive breakdown, which was in accordance with the study conducted in Iraq using the same diagnostic criteria.[7]

In the present study, mandibular molars were comparatively more affected in both the age groups. This was in accordance with the work of Parikh et al.,[17] Baskar and Hegde,[18] and Jasulaityte et al.[20] However, it differed from studies conducted by Weerheijm et al.[24] and Chawla et al.[25] reporting a negligible difference between maxillary and mandibular teeth. Leppaniemi et al.,[10] and Ghanim et al.,[26] reported a greater incidence in maxillary molars. It had been suggested that differences in examination conditions may make it difficult to view maxillary molars as clearly as mandibular molars.[27] In addition, the early eruption of mandibular molars with resultant early posteruptive enamel breakdown or caries makes them more prone than maxillary molars.

In the present study, dental caries was a more frequent finding in hypomineralized molars compared to nonhypomineralized molars. It has been shown that hypomineralization plays a vital role for caries development in the primary dentition.[9] In the permanent dentition, rapid propagation of caries has been reported in hypomineralized molars.[15] This greater incidence of dental caries, combined with compromised, defective enamel results in substantial dental morbidity, which presents a challenge to the clinician.[11,12] The present study has certain pitfalls; first, the age group might not represent the exact prevalence as a younger age group was included and in Group II, pupils with the presence of second primary molar and first permanent molar were included. Another pitfall is the small sample size used for analyzing the susceptibility of hypomineralized teeth for caries study. However, the present study had provided substantial data for future research on MIH and HSPM.

CONCLUSION

Prevalence of hypomineralization defects was 4.88% in Group I and 7.11% in Group II. The most commonly encountered type of hypomineralization defect was demarcated opacities. In Group II, 48% of the subjects diagnosed with MIH had at least one HSPM. Dental caries was more common in hypomineralized molars implicating that hypomineralization plays a critical role in deterioration of the affected tooth and there is a need for increasing the awareness regarding hypomineralization defects and its early prevention.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jalevik B, Noren JG. Enamel hypomineralisation of permanent first molars: A morphological study and survey of possible aetiological factors. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2000;10:278–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2000.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.William V, Messer LB, Burrow MF. Molar incisor hypomineralisation: Review and recommendations for clinical management. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:224–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weerheijm KL. Molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2003;4:114–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weerheijm KL, Duggal M, Mejàre I, Papagiannoulis L, Koch G, Martens LC, et al. Judgement criteria for molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) in epidemiologic studies: A summary of the European meeting on MIH held in Athens, 2003. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2003;4:110–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jälevik B. Prevalence and diagnosis of Molar-Incisor-Hypomineralization (MIH): A systematic review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010;11:59–64. doi: 10.1007/BF03262714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elfrink ME, Schuller AA, Weerheijm KL, Veerkamp JS. Hypomineralised second primary molars: Prevalence data in Dutch 5-year-olds. Caries Res. 2008;42:282–5. doi: 10.1159/000135674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanim A, Manton D, Mariño R, Morgan M, Bailey D. Prevalence of demarcated hypomineralisation defects in second primary molars in Iraqi children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2013;23:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2012.01223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elfrink ME, ten Cate JM, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Moll HA, Veerkamp JS. Deciduous molar hypomineralization and molar incisor hypomineralization. J Dent Res. 2012;91:551–5. doi: 10.1177/0022034512440450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elfrink ME, Schuller AA, Veerkamp JS, Poorterman JH, Moll HA, Ten Cate BJ. Factors increasing the caries risk of second primary molars in 5-year-old Dutch children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010;20:151–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2009.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diniz MB, Rodrigues JA, Hug I, Cordeiro Rde C, Lussi A. Reproducibility and accuracy of the ICDAS-II for occlusal caries detection. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:399–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leppaniemi A, Lukinmaa PL, Alaluusua S. Non-fluoride hypomineralization in the permanent first molars and their impact on the treatment need. Caries Research. 2001;35:36–40. doi: 10.1159/000047428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mejare I, Bergman E, Grindefjord M. Hypomineralized molars and incisors of unknown origin: Treatment outcome at age 18 years. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15:20–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2005.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A review of the development defects of enamel index (DDE Index). Commission on oral health, research and epidemiology. Report of an FDI working group. Int Dent J. 1992;42:411–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jalevik B, Klingberg GA, Barregard L, Noren JG. The prevalence of demarcated demarcated opacities in permanent 1st molars in a group of Swedish children. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:255–60. doi: 10.1080/000163501750541093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weerheijm KL, Groen HJ, Beentjes VE, Poorterman JH. Prevalence of cheese molars in eleven-year-old Dutch children. ASDC J Dent Child. 2001;68:259–62. 229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alaluusua S, Lukinmaa PL, Vartiainen T, Partanen M, Torppa J, Tuomisto J. Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans via mother's milk may cause developmental defects in the child's teeth. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 1996;1:193–7. doi: 10.1016/1382-6689(96)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parikh DR, Ganesh M, Bhaskar V. Prevalence and characteristics of Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation (MIH) in the child population residing in Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2012;13:21–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03262836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhaskar SA, Hegde S. Molar-incisor hypomineralisation: Prevalence, severity and clinical characteristics in 8-to 13-year-old children of Udaipur, India. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2014;32:332–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.140960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittal NP, Goyal A, Gauba K, Kapur A. Molar incisor hypomineralisation: Prevalence and clinical presentation in school children of the northern region of India. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;15:11–8. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jasulaityte L, Veerkamp JS, Weerheijm KL. Molar incisor hypomineralization: Review and prevalence data from the study of primary school children in Kaunas/Lithuania. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2007;8:87–94. doi: 10.1007/BF03262575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuscu OO, Caglar E, Aslan S, Durmusoglu E, Karademir A, Sandalli N. The prevalence of molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH) in a group of children in a highly polluted urban region and a windfarm-green energy island. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19:176–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lygidakis NA, Wong F, Jälevik B, Vierrou AM, Alaluusua S, Espelid I. Best clinical practice guidance for clinicians dealing with children presenting with Molar-Incisor Hypomineralization (MIH): An EAPD Policy Document. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010;11:75–81. doi: 10.1007/BF03262716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weerheijm KL, Mejàre I. Molar-incisor hypomineralization: A questionnaire inventory of its occurrence in member countries of the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry (EAPD) Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:411–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weerheijm KL, Jälevik B, Alaluusua S. Molar-incisor hypomineralisation. Caries Res. 2001;35:390–1. doi: 10.1159/000047479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chawla N, Messer LB, Silva M. Clinical studies on molar-incisor-hypomineralisation Part 1: Distribution and putative associations. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2008;9:180–90. doi: 10.1007/BF03262634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghanim A, Morgan M, Marino R, Bailey D, Manton D. Molar-incisor hypomineralization: Prevalence and defect characteristics in Iraqi Children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2011;21:413–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2011.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zawaideh FI, Al-Jundi SH, Al-Jaljoli MH. Molar incisor hypomineralization: Prevalence in Jordanian children and clinical characteristics. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2011;12:31–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03262776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]