Abstract

Introduction:

Curd (Dadhi) peptides reduce hypertension by inhibiting angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) and serum cholesterol. Peptides vary with bacterial species and milk type used during fermentation.

Aim:

To isolate and assay the antihypertensive peptides, before and after digestion, in two commercially available curd brands in Sri Lanka.

Materials and Methods:

Whey (Dadhi Mastu) separated by high-speed centrifugation was isolated using reverse-phase-high- performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Eluted fractions were analyzed for ACE inhibitory activity using modified Cushman and Cheung method. Curd samples were subjected to enzymatic digestion with pepsin, trypsin, and carboxypeptidase-A at their optimum pH and temperature. Peptides isolated using reverse-phase-HPLC was assayed for ACE inhibitory activity.

Results:

Whey peptides of both brands gave similar patterns (seven major and five minor peaks) in HPLC elution profile. Smaller peptides concentration was higher in brand 1 and penta-octapeptides in brand 2. Pentapeptide had the highest ACE inhibitory activity (brand 2–90% and brand 1–73%). After digestion, di and tri peptides with similar inhibitory patterns were obtained in both which were higher than before digestion. Thirteen fractions were obtained, where nine fractions showed more than 70% inhibition in both brands with 96% ACE inhibition for a di-peptide.

Conclusion:

Curd has ACE inhibitory peptides and activity increases after digestion.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme, curd, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography, peptides, whey

Introduction

Diet plays an important role in promoting and maintaining good health. The current trend in the food industry is towards the development of functional foods with health beneficial properties. In this regard, peptides can be used as nutraceutical ingredients for the prevention or control of blood pressure. One of the most important risk factors for cardiovascular diseases is high blood pressure or hypertension. Blood pressure is controlled by different biochemical pathways.[1]

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is a key objective for the fight against hypertension. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), acts in this system. This enzyme is a zinc metallopeptidase which converts a biologically inactive polypeptide called angiotensin I, to the potent vasoconstrictor known as angiotensin II. Furthermore, ACE catalyzes the degradation of bradykinin, a blood pressure lowering nonapeptide in the kallikrein-kinin system ACE activity inhibition results in an antihypertensive effect.[1] ACE inhibitors also have an effect on the renin-angiotensin system by inhibiting the production of the vasoconstrictor Ang II.[2]

Antihypertensive peptides derived from foods are safer, and these inhibitory peptides can be released by protein hydrolysis or fermentation.[1] ACE inhibitory peptides have been identified in different foods; one of the main sources of these peptides is milk proteins. The protein fraction of milk is composed of 80% casein and the remaining 20% being whey proteins (α-lactalbumin, β-lactoglobulin and immunoglobulins).[3]

Biologically active peptides are produced by enzymatic hydrolysis of proteins or the proteolytic activity of the bacteria during microbial fermentation of milk. Microorganisms can form ACE inhibitory peptides, such as casokinins and lactokinins and other peptides during fermentation. These peptides survive in the intestine and are absorbed into the blood stream. In-vitro studies indicate that milk peptides have an inhibitory effect on ACE activity.[4]

The catabolism of lactose in milk by Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacteria results mainly in the production of lactic acid, or lactic and acetic acids when Bifidobacteria are used in the starter culture.[5] It has been reported that acid producing organisms in fermented dairy products could prolong the lifespan of the consumer. But some people believe that eating dairy products could lead to atherogenic lipid profile. Studies have proven that fermented foods contain live bacteria that influence the chemical composition of the fermented product, especially milk proteins which result in short chain fatty acids.[3] Further short chain fatty acids such as acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid have a feedback inhibition on the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase enzyme which regulates the rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis and reduces the serum cholesterol levels.[3] Reduction in serum cholesterol reduces the formation of atherosclerotic plaque. Not only fermented milk, other proteins such as soy proteins also have cholesterol-lowering effect.[6]

Curd (Dadhi) is a fermented milk product, and it is a common diet since ancient days that provides various health benefits.[7] According to Ayurveda consumption of curd accelerates digestion (Agni), stimulates taste buds and acts as an appetizer. It is ideal for use in conditions like loss of taste, dysuria, and chronic rhinitis. As it absorbs water from intestines, it is widely used to treat diarrhoea and dysentery and mitigates Vata Dosha. Curd has high calcium content and gives lactose intolerant bodies all the nutritive contents of milk.[8]

A fermented milk product with the biologically active peptides valyl-prolyl-proline and isoleucyl-prolyl-proline has been shown to lower blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats.[9] It is suggested that small peptides are absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract without being decomposed by digestive enzymes. Two other peptides (Tyr-Pro and Lys-Val-Leu-Pro-Val-Pro-Gln) that are purified and characterized from fermented milk have been shown to have ACE-inhibitory activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. α-lactorphin (Tyr-Gly-Leu-Phe) also reduced blood pressure in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats.[2] Even though modern ACE inhibitory drugs are available to control hypertension various side effects are also associated with their use such as hypotension, increased potassium levels, reduced renal function, cough, angioedema, skin rashes, and fetal abnormalities. But peptides with ACE inhibitory activity obtained from fermented milk products do not produce such adverse effects when consumed in normal quantity. Therefore, fermented milk products rich in bioactive peptides represent a natural dietary approach which has the potential to control hypertension.[10] Most of the researches on ACE inhibitory peptides were carried out in peptides that were isolated from fermented milk and in spontaneously hypertensive rats. This study mainly focuses on the sustainability of ACE inhibitory peptides from curd after digestion with digestive enzymes.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of whey

Commercially available two curd brands purchased from the local supermarket (three samples from each brand) were centrifuged at 6000 rpm at 4°C[4] using laboratory centrifuge (Sigma 3K30) and the whey fraction was obtained.

Separation of peptides in whey by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

Whey was eluted in a linear gradient from 100% solvent A (0.1% Trifluoroacetic acid in de-ionized water) to 80% solvent B (0.1% Trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile) over 60 min at a flow rate of 1 mL/min in a reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Agilent 1200 series).[4,10] The eluted fractions were monitored at 215 nm[4,10] and 1 mL fractions were collected every minute for ACE inhibitory assay. They were matched with a peptide standard mixture (Sigma H2016) and of Ile-Pro-Ile peptide standard (Sigma 19759) which were eluted with the same solvent gradient.

Analysis of peptides

Qualitative analysis was carried out at room temperature (30°C) by matching the retention time of whey peaks against the retention time of peptide standards in HPLC profiles (Agilent 1200, DAD G1315B). Quantitative analysis was done by calculating the area under the curve in HPLC peaks.

Peptides from digested curd

Each curd sample was mixed well and subjected to sequential enzymatic digestion with pepsin, trypsin, and carboxypeptidase A at their optimum pH and temperature for 24 h.[3] Digested curd was centrifuged and filtrate obtained. Filtrate was subjected to reverse-phase HPLC (C18, silica column, Agilent 1200, DAD G1315B detector) separation at room temperature (30°C) using the same solvent gradient as whey.

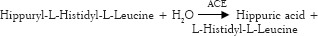

Measurement of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitory activity

The ACE inhibitory activity of each fraction was measured according to the method described by Cushman and Cheung.[11] Fractions were collected, and each fraction of peptide solution (100 μl) was incubated with 20 μl of Hippuryl-L-Histidyl-L-Leucine solution (0.3% w/v) which was pre-incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was initiated by addition of 50 μl of ACE dissolved in de-ionized water (0.1 U/mL), and the mixture was incubated for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 250 μl of 1N HCl. Finally, 2 mL of ethyl acetate was added, and the solution was mixed vigorously for 60 s and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 2 min to obtain a clear separation. One milliliter volume from the clear upper layer was pipetted. These tubes were placed in a water bath, and 1 mL of de-ionized water was added after ethyl acetate has evaporated. The absorbance was recorded at 228 nm against a blank that had the inactive enzyme using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer.[3]

Calculations

The extent of inhibition by the peptides of collected fractions from HPLC was calculated using following equation:

Standard: Absorbance with ACE only

Sample: Absorbance with ACE and ACE inhibitory peptides

Blank: Absorbance without ACE.

Results

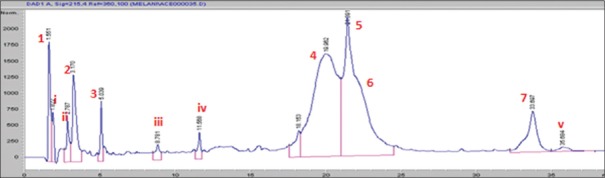

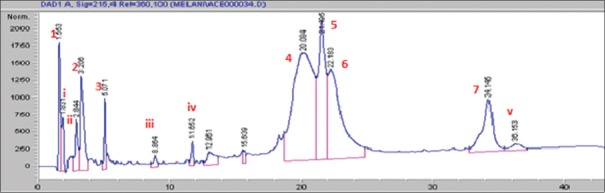

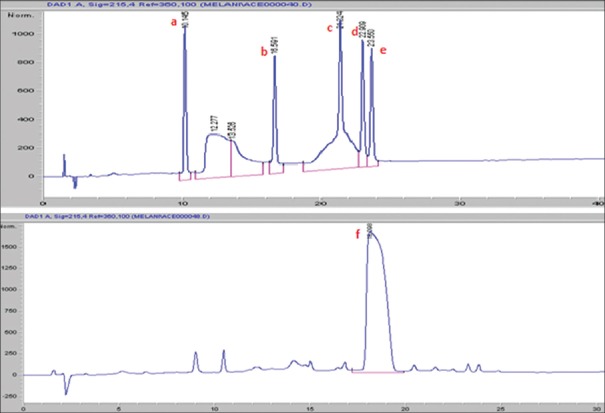

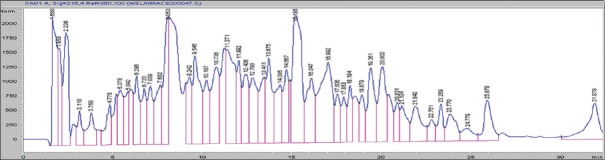

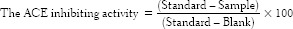

Seven major peaks (1–7) and five minor peaks (i-v) were observed in HPLC elution profile of whey for both brands [Figures 1 and 2]. These peaks were compared with the elution patterns of peptide standards. Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Met (Sigma H2016), Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Leu (Sigma H2016) and Ile-Pro-Ile (Sigma 19759) peptide standards matched with both brands [Figure 3]. The peptide with the highest ACE inhibitory activity was a pentapeptide in both brands with brand 2 having 90% inhibition and brand 1 having 73% inhibition. The sequence of the pentapeptide closely matched with Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Met standard. In brand 2, four fractions gave more than 50% ACE inhibition, whereas in brand 1, two fractions gave more than 50% inhibition. Amino acid and di peptide concentrations were higher in brand 1 and penta to octapeptide concentration was higher in brand 2 [Table 1].

Figure 1.

High-performance liquid chromatography elution profile of whey of brand 1

Figure 2.

High-performance liquid chromatography elution profile of whey of brand 2

Figure 3.

High-performance liquid chromatography elution profile of peptide standards. Peak a Gly-Tyr (10.145 min), Peak b: Val-Tyr-Val (16.591 min), Peak c: Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Met (21.324 min), Peak d: Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Leu (22.909 min), Peak e: Asp-Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe (23.550 min), Peak f: Ile-Pro-Ile (18.098 min)

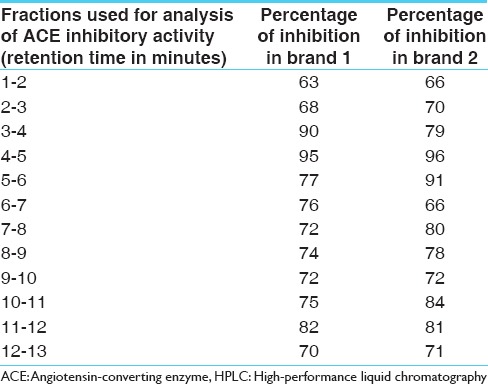

Table 1.

ACE inhibiting activity of different fractions of whey collected after reverse-phase HPLC from two different curd brands (brand 1 and 2)

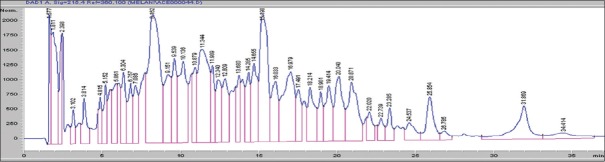

After subjecting to enzymatic digestion, di and tri peptides giving similar inhibition patterns were obtained from both brands [Figures 4 and 5]. Digested peptides gave a higher ACE inhibitory activity than undigested peptides. Nine fractions showed more than 70% inhibition in both brands. Highest ACE inhibition of 96% was obtained for a di peptide. Peptide concentration was higher in brand 2 than brand 1 [Table 2].

Figure 4.

High-performance liquid chromatography elution profile of digested curd of brand 1

Figure 5.

High-performance liquid chromatography elution profile of digested curd of brand 2

Table 2.

ACE inhibiting activity of different fractions of digested curd collected after reverse-phase HPLC from two different brands (brand 1 and 2)

Discussion

Fermented milk products have been a part of the human diet for more than thousands of years. It provides a wider range of nutrition including protein, fat, lactose, water, vitamins, and minerals, and is often regarded as a complete food as it is capable of sustaining life on its own.

Milk contains several amino acids such as, aspartic acid, threonine, serine, glutamic acid, proline, glycine, alanine, valine, methionine, isoleucine, leucine, tyrosine, phenylalanine, histidine, lysine, and arginine.[12] These amino acids can show different bioactive properties according to the peptide sequence they form.

Bioactive peptides from milk proteins can be released by enzymatic proteolysis, gastrointestinal digestion, or food processing. These peptides can exert a wide range of effects, such as antimicrobial, antihypertensive, antithrombotic, immunomodulatory, opioid properties, and enhance the mineral absorption of calcium.[13] Furthermore, fermented milk products have lower lactose content and can be tolerated by lactose intolerance individuals.[14]

The determination of milk peptides has been studied by several chromatographic and electrophoretic techniques. Chromatographic techniques such as gel filtration chromatography, paper chromatography, thin layer chromatography, ion-exchange chromatography, affinity chromatography, and HPLC are widely used in protein analysis. In particular, HPLC is most commonly used in isolation, purification, and characterization of peptides.

Peptides formed during fermentation depend on the bacterial culture and the type of milk that is used. Common starter cultures that are used in Sri Lankan curd production are Lactobacillus bulgaricus and S. thermophilus.

Studies indicate several peptides were isolated from milk and yoghurt by reverse phase HPLC, such as Val-Tyr-Pro-Phe-Pro-Gly, Gly-Lys-Pro, Ile-Pro-Ala, Phe-Pro, Val-Tyr-ProVal-Pro-Pro.[13] Ile-Pro-Pro [8] Tyr-Pro and Lys-Val- Leu-Pro-Val-Pro-Gln and Tyr-Gly-Leu-Phe [2] had higher ACE inhibitory property. In our study high ACE inhibitory property was shown by di and tripeptides in digested curd and penta to octapeptides in whey. Those peptides had sequence that closely matched with Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Met, Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Leu and Ile-Pro-Ile.

Whey of both brands had similar HPLC peak patterns indicating the presence of similar peptides and these peptides did not have a significant difference in ACE inhibition. But the area under the curve in the two HPLC profiles differed indicating that peptide concentrations are different in the two brands even after fermentation with the same bacterial species.

Our study indicated that curd gave a higher ACE inhibiting activity after digesting with pepsin, trypsin and carboxypeptidase-A indicating that curd has higher ACE inhibitory effect after digestion. This inhibition was even higher than the ACE inhibitory activity of whey. Similar enzymatic study with HPLC separation technique has been carried out,[15] in cheese whey as well.

Peak patterns of curd after digestion by enzymes were similar in both brands. The concentration of small peptides was much higher than whey suggesting after digestion with digestive enzymes formation of small peptides has increased. Both brands also had higher ACE inhibiting activity than whey and high ACE inhibition was expressed with di-peptides wherein whey high ACE inhibition was shown by a pentapeptide.

The majority of curd-derived ACE-inhibitory peptides had relatively short chains. This is consistent with findings of previous research work.[16] Where they demonstrated that large peptide molecules do not fit into the active site of ACE. It seems that a peptide binding to ACE is strongly influenced by the C-terminal tripeptide sequence of the peptide. Many ACE-inhibitory peptides have hydrophobic amino acid residues at each of the three C-terminal positions and mainly proline at the C-terminal end.

According to our study, HPLC profiles of whey and HPLC profiles of digested curd have different peak patterns suggesting presence of different peptides. Following digestion with enzymes, the ACE inhibiting activity of curd increased in each and every fraction. This may be due to inhibition of the ACE enzyme by the small peptides formed after digestion. The ACE inhibiting activity of whey prior to digestion could be due to the peptides formed during fermentation by the lactic acid bacteria. This study indicates that ACE inhibitory activity can vary according to the milk type, bacterial culture, and the amount of digestion that has taken place in the human intestine. Our study also indicates that whey and digested curd have the potential to be a good functional food in hypertensive subjects. Thus, utilization and popularization of curd in the general population as a functional food for hypertensive people would be a cost-effective method of decreasing the morbidity associated with hypertension.

Conclusion

This study indicates that whey and digested curd have ACE inhibitory peptides hence has the potential to be a good functional food in hypertensive subjects. The peptides and inhibition may vary with bacterial species and milk type used during fermentation.

Financial support and sponsorship

University of Jaywardenepura, Gangodawila, Nugegoda, Srilanka grant (ASP/6/R/2010/8).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jakala P, Vapaatalo H. Antihypertensive peptides from milk proteins: A review. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:251–72. doi: 10.3390/ph3010251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seppo L, Jauhiainen T, Poussa T, Korpela R. A fermented milk high in bioactive peptides has a blood pressure-lowering effect in hypertensive subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:326–30. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Athiththan LV, Jayaratne SD, Peiris H, Jayesekara S. The effect of milk proteins and curd on serum Angiotensin converting enzyme activity and lipid profile in Wistar rats. J Natl Sci Found. 2009;37:209–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura Y, Yamamoto N, Sakai K, Okubo A, Yamazaki S, Takano T. Purification and characterization of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitors from sour milk. J Dairy Sci. 1995;78:777–83. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(95)76689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamime AY, Robinson RK. Yoghurt Science and Technology. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Wood Head Publishing Limited; 2007. pp. 432–3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erdman JW., Jr AHA Science Advisory: Soy protein and cardiovascular disease: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the AHA. Circulation. 2000;102:2555–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.20.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priyanka BV, Mallika KJ. Dietic practice of curd: Demographic survey. Ayurpharm Int J Ayurveda Allied Sci. 2013;2:364–71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayurveda and Health Tourism. Sour but Saver. 2011. [Last cited on 2014 Aug 24]. Available from: http://www.ayurvedamagazine.org/sour-but-saver .

- 9.Gonzalez CR, Tuohy KM, Jauregi P. Production of angiotensin-I-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity in milk fermented with probiotic strains: Effects of calcium, pH and peptides on the ACE-inhibitory activity. Int Dairy J. 2011;21:615–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto N, Maeno M, Takano T. Purification and characterization of an antihypertensive peptide from a yogurt-like product fermented by Lactobacillus helveticus CPN4. J Dairy Sci. 1999;82:1388–93. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(99)75364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cushman DW, Cheung HS. Spectrophotometric assay and properties of the angiotensin-converting enzyme of rabbit lung. Biochem Pharmacol. 1971;20:1637–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(71)90292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne-Botha S, Bigwood EJ. Amino-acid content of raw and heat-sterilized cow's milk. Br J Nutr. 1959;13:385–9. doi: 10.1079/bjn19590052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeBlanc JG, Matar C, Valdéz JC, LeBlanc J, Perdigon G. Immunomodulating effects of peptidic fractions issued from milk fermented with Lactobacillus helveticus. J Dairy Sci. 2002;85:2733–42. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(02)74360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhat ZF, Bhat H. Milk and dairy products as functional foods. A Review. Int J Dairy Sci. 2010;6:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abubakar A, Saito T, Kitazawa H, Kawai Y, Itoh T. Structural analysis of new antihypertensive peptides derived from cheese whey protein by proteinase K digestion. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81:3131–8. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75878-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Natesh R, Schwager SL, Sturrock ED, Acharya KR. Crystal structure of the human angiotensin-converting enzyme-lisinopril complex. Nature. 2003;30(421):551–4. doi: 10.1038/nature01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]