Abstract

Background and Aims:

We undertook this study to assess if a small-dose of dexmedetomidine (DEX) for conscious sedation during awake fiberoptic intubation (AFOI) in simulated cervical spine injury (CSI) patients provides optimum conditions and fulfills the need of postintubation neurological examination required in such patients. The aim was to assess the efficacy of DEX on arousability and patient's comfort during AFOI in simulated CSI patients.

Material and Methods:

In this prospective, randomized double-blind study, 100 American Society of Anesthesiologists Grade I-II patients aged between 18 and 65 years scheduled for elective surgery under general anesthesia underwent AFOI under conscious sedation with DEX. After locally anesthetizing the airway and applying a cervical collar, patients either received DEX 1 μg/kg over 10 min followed by 0.7 μg/kg/h maintenance infusion or normal saline in the same dose and rate during AFOI. Targeted sedation (Ramsay sedation score [RSS] ≥2) during AFOI was maintained with midazolam [MDZ] in both groups. Statistical Analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t-test, Chi-square test, Mann-Whitney test and Wilcoxon-w test.

Results:

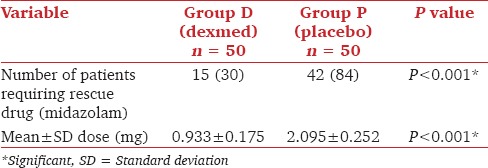

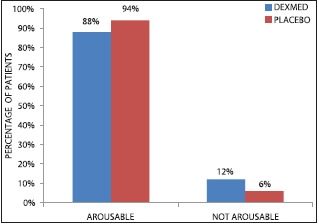

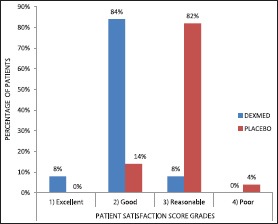

The total number of patients requiring MDZ and the mean dose of MDZ required to achieve targeted sedation (RSS ≥2) was significantly less in DEX group compared to the placebo group (P < 0.001). Similarly, patient satisfaction score, heart rate, systolic, diastolic and mean arterial pressure and respiratory parameters were significantly better in DEX group (P < 0.001). Postintubation arousability in the two groups was comparable (P = 0.29).

Conclusions:

Dexmedetomidine provides optimum sedation without compromising airway or hemodynamic instability with better patient tolerance and satisfaction for AFOI. It also preserves patient arousability for the postintubation neurological assessment.

Keywords: Awake fiberoptic intubation, cervical spine injury, dexmedetomidine

Introduction

Meticulous airway management with maintenance of the cervical spine alignment and provision of continuous immobilization are an integral part of care of the cervical spine injury (CSI) patients. Concern about the possibility of cervical spinal cord injury when extending the head and flexing the neck for direct laryngoscopy and intubation leads many anesthesiologists to prefer awake fiberoptic intubation (AFOI) in patients with CSI.

Awake fiberoptic intubation is either performed in a completely awake patient without sedation after anesthetizing the airway or under conscious sedation. There are advantages and disadvantages of both approaches. Awake intubation can provoke anxiety and can lead to discomfort to the patient. With the conscious sedation, the sedation needs to be carefully titrated as it can lead to hypoventilation, whereas inadequate sedation leads to discomfort, anxiety and excessive sympathetic discharge. Various pharmacological methods have been reported to achieve conscious sedation for AFOI including fentanyl, midazolam (MDZ), ketamine, propofol, remifentanil, and dexmedetomidine (DEX).[1]

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective and specific alpha 2 adrenoreceptor agonist and has properties making it suitable for AFOI. In addition to hemodynamic stability, anxiolytic and analgesic properties, it results in sedation while maintaining easy arousability. DEX demonstrates minimal respiratory depression[2] even at higher doses and also decreases salivary secretions, which is desirable during AFOI.[3,4,5]

The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of DEX 1 μg/kg over 10 min followed by 0.7 μg/kg/h infusion in providing optimum conditions for AFOI in simulated CSI patients.

Material and Methods

After obtaining Institutional Research and Ethics Committee Approval, written informed consent for this double-blind trial was obtained from 100 healthy patients between the age groups 18-65 years. Patients belonging to American Society of Anesthesiologists Grade I or II, with Mallampati Grade I or II, scheduled for elective surgery requiring general anesthesia were included in the study conducted during the period from March 2012 to June 2013.

Using alpha 0.05 and beta 0.2, we calculated that at least 38 patients per group would be required to detect a significant difference in number of patients requiring rescue drug to achieve proper sedation (Ramsay sedation score [RSS] ≥2) between the two groups. Hence, we recruited 50 patients in each group.

The criteria for exclusion were patients with a history of allergy to DEX, concomitant use of medications, which may exaggerate the heart rate (HR) response of DEX including digoxin or β-adrenergic antagonists, HR <50 beats/min, systolic blood pressure (SBP) <90 mm Hg, pregnancy, nursing women and morbid obesity. Patients on anticoagulants, nasal trauma, deformity or polyp, liver transaminase enzymes ≥2 times upper normal limit and surgery <1 h duration were also excluded.

Patients were premedicated with 0.5 mg oral alprazolam and 150 mg ranitidine the night before surgery and were allocated into two groups on the basis of even and odd number distribution. DEX group, (Group D, n = 50): Received intravenous (IV) DEX (1 μg/kg) over 10 min followed by DEX infusion at the rate of 0.7 μg/kg/h. Placebo group, (Group P, n = 50) received IV normal saline bolus (1 ml/kg) over 10 min, followed by normal saline infusion at the rate of 0.7 ml/kg/h.

In the preoperative area, patient's HR, blood pressure (BP) (SBP, diastolic blood pressure [DBP], mean arterial pressure [MAP]), SpO2 were recorded, and 20G IV cannula was placed on the dorsum of a hand for drug and continuous fluid administration. Glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg was given intramuscularly 45 min before the surgery. Nasal patency was confirmed, and 2-3 drops of 0.1% xylometazoline were instilled in both the nostrils. Lignocaine up to a maximum dose of 5 mg/kg was used to topicalize the airway of each patient. Based on the total lignocaine dose calculated as per weight of the patient, all patients were nebulized with 4-5 ml of 4% lignocaine through ultrasonic nebulizer. On arrival in the operating room, the patient's baseline HR, BP and oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded. Pledgets soaked in 2% lignocaine with adrenaline were placed in both the nostrils one by one for 10 min and 2-3 puffs of 10% lignocaine was sprayed on oropharynx and base of the tongue. Transtracheal block with 2-3 ml of 2% lignocaine, was given to the patient on the operating table, eliciting a cough without significant cervical motion. Then patient's neck was immobilized with semi rigid cervical collar (Philadelphia cervical collar, Tynore, India).

Infusion of DEX (1 μg/kg) over 10 min (loading dose) followed by a continuous infusion (maintenance dose) of DEX (0.7 μg/kg/h) in Group D and 0.9% Normal Saline (1 ml/kg) over 10 min (loading dose) followed by continuous infusion (maintenance dose) of normal saline (0.7 ml/kg/h) in Group P was administered IV as per group allocation of the patient. Infusion was prepared by an anesthesia resident not participating in the study. The anesthetist doing AFOI and the anesthesia resident noting the parameters were blinded to the drug given to the patient.

Ramsay sedation score, was assessed after the loading dose of DEX or normal saline and thereafter every 2 min from the beginning of the maintenance dose till the completion of the fiberoptic intubation procedure. Any patient having RSS <2 was given MDZ as the rescue drug, in the dose of 0.5 mg intravenously in repeated doses until RSS ≥2 was attained, or a total maximum dose of 0.1 mg/kg was achieved, whichever was earlier. After confirming suppressed gag reflex and RSS ≥2, fiberoptic bronchoscopy (using Karl Storz, 5 mm adult fiberoptic bronchoscope) was done by an anesthesiologist experienced in bronchoscopy. After visualization of carina, prewarmed loaded endotracheal tube (size 6.5 in females and 7.0 in males) was slid over the bronchoscope. Placement of endotracheal tube was confirmed by recording end tidal carbon dioxide and chest auscultation. If the patient remained inadequately sedated (RSS <2) after a total MDZ dose of 0.1 mg/kg, propofol was given in incremental doses of 5 mg intravenously until RSS ≥2 is attained, or a total maximum dose of 1 mg/kg was achieved and fiberoptic intubation was completed in the same manner. Patients requiring propofol were excluded from the study. After the confirmation of intubation, the study drug was stopped, arousability of the patient was checked by asking them to move their hand and the cervical collar was removed. Subsequently, general anesthesia was administered as per routine protocol, and scheduled surgery was completed. All the patients were given oxygen through nasal cannula at the rate of 4 L/min throughout the AFOI procedure.

Vital signs were recorded at baseline and every 3 min from the start of study drug infusion until completion of AFOI. Baseline values of SBP, DBP, SpO2, HR, respiratory rate (RR) were used to define adverse events requiring study discontinuation and/or therapeutic intervention. Hypotension was defined as SBP <80 mmHg, DBP <50 mmHg, or SBP <30% below baseline. Hypertension was defined as SBP >180 mmHg, DBP >100 mmHg, or a SBP increase to >30% mmHg above baseline. Bradycardia was defined as HR <50 beats/min or a decrease to <30% below baseline. Tachycardia was defined as HR >120 beats/min or increase to >30% above baseline. Respiratory depression was defined as RR <8 breaths/min or a decrease to <25% below baseline. Hypoxia was defined as SpO2 <90% or a decrease to <10% below baseline saturation.

Hypotension was treated with fluid infusion followed by mephenteramine if there was no response to fluid infusion. Bradycardia was treated with atropine. In case the patient did not tolerate the procedure the cervical collar was removed, study procedure was abandoned and anesthesia was induced as per routine protocol and scheduled surgery was completed. That particular patient was excluded from the study.

At the 24 h postoperative follow-up, the patient was assessed for satisfaction in terms of recall, anxiety and pain (pain assessed using 10 cm visual analog scale) during AFOI on a scale of 1-4 [1-excellent, 2-good, 3-reasonable, 4-poor].

The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage of patients requiring MDZ for rescue to achieve/maintain targeted sedation (RSS ≥2) throughout the AFOI procedure in each group. Secondary endpoints were total dose of MDZ required, patient's satisfaction for the procedure (in terms of recall, anxiety, and pain), assessed 24 h postoperatively and arousability after intubation in each group. Any adverse events or complications during intraoperative period were mentioned separately. Sedation was assessed using RSS.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 16.0) statistical software using unpaired Student's t-test, Chi-square test, Mann-Whitney test, and Wilcoxon-w test, as appropriate. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

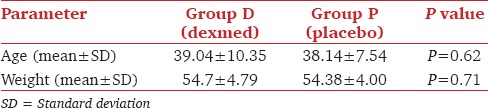

Two patients from the placebo group were excluded as they required propofol for targeted sedation (RSS ≥2). The demographic profile was similar in both the groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile

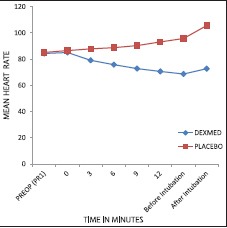

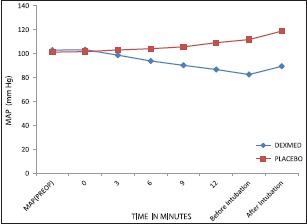

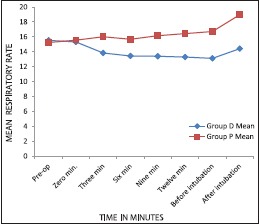

Mean HR and MAP decreased in the DEX group and increased in the placebo group (P < 0.001) [Graphs 1 and 2]. Respiratory rate decreased in DEX group and increased in the placebo group throughout the AFOI procedure [Graph 3]. (P < 0.001). Although RR decreased in DEX group none of the patients had respiratory depression.

Graph 1.

Comparison of mean heart rate between the groups

Graph 2.

Comparison of mean arterial pressure between the groups

Graph 3.

Comparison of respiratory rate between groups

There was a gradual increase in mean RSS from 2.7 to 2.92 (RSS 6) during bronchoscopy in Group D whereas it increased from 1.9 to 2.23 in Group P. RSS was higher in Group D at every point of observation until intubation (P < 0.05).

The number of patients requiring MDZ for achieving target sedation and the dose required are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison number of patients requiring and the dose of midazolam

Both groups were statistically comparable in arousability after the procedure (P = 0.29) [Graph 4].

Graph 4.

Number of patients showing postintubation arousability in two groups

Patients in Group D were significantly more satisfied than those in Group P [Graph 5].

Graph 5.

Comparison of patient satisfaction score between groups

Significantly more patients (n = 12) had bradycardia P < 0.05 and hypotension (n = 6) in Group D (P = 0.01) compared with Group P. However, only one patient required atropine for treating bradycardia in Group D. In Group P, significantly more number of patients had tachycardia P < 0.05 compared with Group D. Both groups were statistically comparable for hypertension during the procedure (P = 0.07).

Discussion

Our study indicates that DEX in the dose of 1 μg/kg over 10 min followed by 0.7 μg/kg/h provides hemodynamic stability, no respiratory depression, arousability and good patient satisfaction for AFOI in simulated CSI patients.

Dexmedetomidine, has several unique properties, including sedation, anxiolysis, analgesia, amnesia, hemodynamic stability, antisialagogue effects, a unique respiratory-sparing effect and arousability that make it ideally suited for the management of difficult and critical airways like CSI patients requiring postintubation neurological examination.[2,6,7,8]

Dose of 1 μg/kg bolus over 10 min followed by 0.7 μg/kg/h has been used for procedural sedation including AFOI in various studies.[5,9]

Dexmedetomidine causes a decrease in HR and BP by an inhibition of central sympathetic outflow that overrides the direct effects of DEX on the vasculature.[8] Our hemodynamic results were comparable to those of Bergese et al.[5] Bradycardia from DEX may have been mitigated in our study by the use of glycopyrrolate. On the other hand, the use of glycopyrrolate in Group P might have led to an additive increase in HR. We did not see a biphasic response of BP with DEX in our patients, which is similar to the findings of Jorden et al.[10] and Ramsay and Luterman.[11]

Dexmedetomidine causes minimal respiratory impairment and does not decrease arterial oxygen saturation <90[8] even when given in large doses. Ramsay and Luterman[11] also reported use of high doses of DEX (1-5 μg/kg/h) in three patients and showed that the airway was maintained along with adequate respiratory drive.

Our results with regard to MDZ requirements are in accordance with Bergese et al.[5] Venn and Grounds[12] reported 3 times less alfentanil requirement in DEX group than propofol group to maintain equivalent sedation (RSS = 5).

We found that the number of patients who were arousable and could follow commands after study drug infusion in two groups were comparable in both the groups (P = 0.29) indicating that a small-dose infusion of DEX provided sedation that could easily be reversed by verbal stimuli and hence can be used for performing neurological examination after AFOI particularly in CSI patients. Our results are in accordance with Avitsian et al.[7] and Grant et al.[9] who also reported arousability for neurological examination after using DEX.

Abdelmalak et al.,[3] have reported a series of successful awake fiberoptic intubations in 5 patients with critical (unstable, difficult) airways using DEX. All of the patients were comfortable during the procedure. Bergese et al.[13] concluded that the DEX-MDZ patients had less pain and discomfort and were more satisfied than MDZ only patients.

Because the protocol of this study did not allow for titration of the DEX infusion the percentage of patients requiring rescue MDZ may have been overestimated.

Finally, a thoroughly anesthetized airway is essential for successful AFOI. Although the protocol standardized the topicalization process with lignocaine, there was variability among patients in the quality of local anesthetic block, which might have led to variation in results.

We conclude that DEX in the dose of 1 μg/kg over 10 min followed by 0.7 μg/kg/h, provides optimum conditions with stable hemodynamics for conscious sedation during AFOI in simulated CSI patients with its property to maintain arousability and hence help enable postintubation neurological assessment of the CSI patient. As we used a fixed dose of DEX and did not titrate it during the procedure, more studies are required to determine accurate dose of DEX required for AFOI in CSI patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Johnston KD, Rai MR. Conscious sedation for awake fibreoptic intubation: A review of the literature. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:584–99. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-9915-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebert T, Maze M. Dexmedetomidine: Another arrow for the clinician's quiver. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:568–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200409000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdelmalak B, Makary L, Hoban J, Doyle DJ. Dexmedetomidine as sole sedative for awake intubation in management of the critical airway. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19:370–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maroof M, Khan RM, Jain D, Ashraf M. Dexmedetomidine is a useful adjunct for awake intubation. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:776–7. doi: 10.1007/BF03016576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergese SD, Candiotti KA, Bokesch PM, Zura A, Wisemandle W, Bekker AY, et al. A Phase IIIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study evaluating the safety and efficacy of dexmedetomidine for sedation during awake fiberoptic intubation. Am J Ther. 2010;17:586–95. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181d69072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jooste EH, Ohkawa S, Sun LS. Fiberoptic intubation with dexmedetomidine in two children with spinal cord impingements. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1248. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000173765.94392.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avitsian R, Lin J, Lotto M, Ebrahim Z. Dexmedetomidine and awake fiberoptic intubation for possible cervical spine myelopathy: A clinical series. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2005;17:97–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ana.0000161268.01279.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yazbek-Karam VG, Aouad MM. Perioperative uses of dexmedetomidine. Middle East J Anesthesiol. 2006;18:1043–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant SA, Breslin DS, MacLeod DB, Gleason D, Martin G. Dexmedetomidine infusion for sedation during fiberoptic intubation: A report of three cases. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16:124–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2003.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorden VS, Pousman RM, Sanford MM, Thorborg PA, Hutchens MP. Dexmedetomidine overdose in the perioperative setting. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:803–7. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsay MA, Luterman DL. Dexmedetomidine as a total intravenous anesthetic agent. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:787–90. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200409000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venn RM, Grounds RM. Comparison between dexmedetomidine and propofol for sedation in the intensive care unit: Patient and clinician perceptions. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:684–90. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergese SD, Patrick Bender S, McSweeney TD, Fernandez S, Dzwonczyk R, Sage K. A comparative study of dexmedetomidine with midazolam and midazolam alone for sedation during elective awake fiberoptic intubation. J Clin Anesth. 2010;22:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]