Abstract

Background

Ocimum americanum var. pilosum is a chilling-sensitive, widely distributed plant that is consumed as a vegetable in central and southern China. To increase our understanding of cold stress responses in this species, we performed de novo transcriptome assembly for O. americanum var. pilosum and compared the transcriptomes of plants grown under normal and low temperatures.

Results

A total of 115,022,842 high quality, clean reads were obtained from four libraries (two replicates of control samples and two replicates of chilling-treated samples) and were used to perform de novo transcriptome assembly. After isoforms were considered, 42,816 unigenes were generated, 30,748 of which were similar to known proteins as determined by a BLASTx search (E-value < =1.0E-05) against NCBI non-redundant, Swiss-Prot, Gene Ontology, KEGG, and Cluster of COG databases. Comparative analysis of transcriptomes revealed that 5179 unigenes were differentially expressed (with at least 2-fold changes, FDR < 0.01) in chilling-treated samples, and that 2344 and 2835 unigenes were up- and down-regulated by chilling stress, respectively. Expression of the 10 most up-regulated and the five most down-regulated unigenes was validated by qRT-PCR. To increase our understanding of these differentially expressed unigenes, we performed Gene ontology and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. The CBF-mediated transcriptional cascade, a well-known cold tolerance pathway, was reconstructed using our de novo assembled transcriptome.

Conclusion

Our study has generated a genome-wide transcript profile of O. americanum var. pilosum and a de novo assembled transcriptome, which can be used to characterize genes related to diverse biological processes. This is the first study to assess the cold-responsive transcriptome in an Ocimum species. Our results suggest that cold temperature significantly affects genes related to protein translation and cellular metabolism in this chilling sensitive species. Although most of the CBF pathway genes have orthologs in O. americanum var. pilosum, none of the identified cold responsive (COR) gene orthologs was induced by cold, which is consistent with the lack of cold tolerance in this plant.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-016-2507-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Chilling tolerance, RNA-seq, Gene regulation, O. americanum

Background

Species in the genus Ocimum are native to Africa, South America, and Asia, and are valued as aromatic and medicinal plants. Essential oils extracted from Ocimum spp., such as O. basilicum, O. sanctum, and O. americanum, have anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and larvicidal activities [1–4]. Recently, the transcriptomes of O. basilicum and O. sanctum were assembled and used to identify genes involved in the biosynthesis of essential oils and medicinal metabolites [5, 6]. In addition to being used for medicinal purposes in some parts of the world [2–4], O. americanum var. pilosum of the Lamiaceae family is one of the most popular vegetables in Anhui and Henan provinces in China, where it is frequently grown. O. americanum var. pilosum is very sensitive to chilling injury, however, which limits its growing area and can also dramatically reduce its yield, leading to economic losses for farmers.

Low temperature is a major environmental factor determining the growth and productivity of plants. Temperate plants are tolerant to chilling temperatures (0-15 °C) but are usually intolerant of freezing temperatures (<0 °C) [7]. For many temperate plant species, a period of exposure to chilling temperatures increases plant tolerance to subsequent freezing conditions in a phenomenon known as “cold acclimation” [7]. In contrast, plants of tropical and subtropical origins are intolerant of chilling and freezing temperatures. In response to low temperature, many biochemical and physiological processes change in plants through regulation of cold responsive (COR) gene expression as well as through posttranslational protein modifications. The ICE1-CBF-COR transcriptional cascade (inducer of CBF expression 1 and C-repeat binding factor transcriptional cascade) is the best characterized pathway for gene regulation under cold conditions in many species [8]. In Arabidopsis, three transcription factors in the CBF family (CBF1, CBF2, and CBF3) are rapidly induced by low temperatures [9]. These CBFs can bind to and activate downstream COR genes, such as COR15, COR47, COR78, and KIN1, to protect plant cells from freezing damage. The pathway may also be important for chilling tolerance [10]. Under cold conditions, the expression of CBFs can be regulated by several upstream transcription factors such as ICE1, CAMTAs, MYB15 and EIN3 [11]. The protein kinase OST1 (open stomata 1) was recently found to phosphorylate ICE1 under cold stress and to thereby stabilize and activate ICE1 activity [12]. SIZ1 (SAP and Miz 1), a SUMO (small ubiquitin related modifier) E3 ligase, can stabilize ICE1 through sumoylation [13]. ICE1 protein stability and activity can also be regulated by E3 ligase HOS1 (high expression of osmotically responsive gene1)-mediated protein ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation under cold stress [14].

RNA-seq technology is increasingly being used to characterize transcriptomic events in plants. RNA-seq can provide transcriptomic information in the absence of a reference genome, and thus it is particularly useful in non-model species, whose genomic sequences are often unavailable. For many crops and other economically important plants, a period of unexpected low temperature may cause damage to plants and result in great losses to farmers. Recently, a number of studies have characterized cold responsive transcriptomes of these plants, including important crops such as Prunus dulcis Mill. (Almond) [15], Beta vulgaris L. (Sugar beet) [16] and Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. (Trifoliate orange) [17] and other plants with high economic value, such as Eucalyptus dunnii [18], Chrysanthemum nankingense [19], and Lilium longiflorum (Easter lily) [20, 21]. These studies suggested that the gene expression responses of plants to cold are complex and involve numerous cellular processes, such as carbohydrate metabolism, protein metabolism, calcium signaling and hormonal changes [17–20].

In this study, we performed de novo transcriptome assembly of O. americanum var. pilosum and compared its transcriptomes under normal and chilling conditions to investigate how O. americanum var. pilosum responds to low temperature stress. In the de novo assembled transcriptome of O. americanum var. pilosum, we identified 42,816 active transcribed unigenes and found that the expression of 5179 unigenes was up- or down-regulated in response to low temperature. To understand the potential involvement of the CBF pathway in the cold response of O. americanum var. pilosum, we reconstructed the CBF pathway by using our de novo assembled transcriptome and compared the expression of CBF pathway factors before and after chilling treatment. We found that none of the identified COR gene orthologs was induced by cold in O. americanum var. pilosum, which is consistent with the cold sensitive phenotype of this plant. In contrast, many of the cold regulated genes have functions related to protein translation and cellular metabolism, suggesting that cold temperature affects this chilling sensitive plant by altering protein synthesis and metabolism.

Results and discussion

Response of O. americanum var. pilosum to chilling stress

Seeds of O. americanum var. pilosum were collected from Funan County of Anhui Province, China. Seeds were germinated on MS agar medium. Then 5-day-old seedlings were transferred to soil and grown in a growth room with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod at 22 °C. Chilling treatment was performed in a climate chamber with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod at 4 °C. During chilling treatment, control plants were kept at 22 °C. Mint (Mentha spicata, family Lamiaceae) belonging to the same family with O. americanum var. pilosum was used as a control (a chilling-tolerant plant) in the chilling sensitivity test. As shown in Fig. 1a, 10-day-old O. americanum var. pilosum and control plants appeared healthy before they were subjected to chilling stress. After a chilling stress of 4 °C for 7 d, the control seedlings but not the O. americanum var. pilosum seedlings survived, indicating that O. americanum var. pilosum is highly susceptible to chilling jury. When 30-day-old plants were subjected to chilling stress, the results once again indicated that chilling sensitivity is greater for O. americanum var. pilosum than for the control (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Chilling sensitivity of (a) 10- and (b) 30-day-old O. americanum var. pilosum plants. Mentha spicata was used as the control

RNA sequencing and de novo transcriptome assembly

Total RNA was isolated from both untreated (control) and chilled (4 °C, 12 h) 30-day-old O. americanum var. pilosum leaves. RNA sequencing with Illumina HiSeq2500 was performed for two biological replicates of control and chilled samples, which were designated control_rep1, control_rep2, chilling_rep1, and chilling_rep2. About 40 million paired-end reads were produced for each RNA-seq sample (Table 1). Clean reads were acquired from initial paired-end reads after low quality regions (Q < 20), PCR duplicates, and adaptor sequences were trimmed. For each control sample, approximately 30 million clean reads containing a total of 3 billion nucleotides were obtained (Table 1). For each chilling-treated sample, approximately 27 million clean reads containing a total of 2.7 billion nucleotides were obtained (Table 1). Biological replicates produced comparable data (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sequencing output statistics in four O. americanum var. pilosum leaf samples from plants that were not chilled (Control_rep1 and 2) or chilled (Chilling _rep 1 and 2)

| Sample | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Control_rep1 | Control_rep2 | Chilling_rep1 | Chilling_rep2 |

| Number of raw reads | 40,417,224 | 41,271,492 | 39,558,950 | 40,285,850 |

| Number of clean reads | 30,413,692 | 30,946,028 | 26,653,114 | 27,010,008 |

| Percentage of reads kept | 75 | 75 | 67 | 67 |

| Size of clean reads (bp) | 3,071,782,892 | 3,125,548,828 | 2,691,964,514 | 2,728,010,808 |

| Number of total clean reads | 115,022,842 | |||

We pooled all high quality reads (115,022,842) from the four samples to perform the de novo transcriptome assembly (Table 1). With the Trinity program [22], 93,850 transcripts were assembled with an N50 length of 1283 bp, an average transcript length of 958 bp, and a maximal transcript length of 9,543 bp (Table 2). We chose the longest isoform of each gene to construct the unigene set. After isoforms were considered, these assembled transcripts were predicted to be produced from a total of 42,816 unigenes (Additional file 1: Table S1). The mean size of the unigenes was approximate 947 bp, and their lengths ranged from 300 bp to 9,543 bp (Table 2). We compared transcriptome of O. americanum var. pilosum with that of another species of Ocimum, O. sanctum. Previous published transcriptome of O. sanctum was used in this analysis [5, 6]. We found that 71 % of unigenes (30577) in O. americanum var. pilosum got hits (E-value < =1.0E-05) in the transcriptome of O. sanctum, suggesting high similarity between these two species. The 29 % of unigenes that don’t get hits may reflect the genomic diversity between the two different species.

Table 2.

Statistics of transcriptome assembly and predicted unigenes

| Variable | Total number of assembled transcripts | Number of predicted unigenes |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 93,850 | 42,816 |

| Size of data (bp) | 89,919,719 | 40,526,158 |

| Minimum length (bp) | 201 | 300 |

| Maximum length (bp) | 9543 | 9543 |

| Mean length (bp) | 958 | 947 |

| N50 length (bp) | 1283 | 1346 |

As indicated by the length distribution of O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes (Fig. 2), most unigenes (38783, 90.6 %) had < 2000 nucleotides, and the number of unigenes decreased as gene length increased. Genes with only one transcript were considered to be distinct singletons, while genes with multiple transcripts were considered to be distinct clusters. Among 42,816 unigenes, 24,196 unigenes were distinct singletons, and about 18,620 unigenes were distinct clusters.

Fig. 2.

The distribution of unigene lengths for O. americanum var. pilosum

Annotation and classification of O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes

To identify the putative functions of O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes, we carried out functional annotation by using a BLASTx search (E-value < =1.0E-05) against several protein databases: NCBI non-redundant (nr) database, Swiss-Prot database, Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes, Genomes (KEGG) database, and Cluster of Orthologous Group (COG) database. Of the 42,816 unigenes, 71.5 % (30,628 unigenes) were successfully aligned to known proteins in the nr database (Table 3). In the other four databases (SwissProt, GO, KEGG, and COG), 24,531, 10,172, 8,533, and 28,853 unigenes were successfully aligned to known proteins (Table 3), respectively. Overall, 30,748 (71.8 %) unigenes were significantly similar to known proteins in the five databases, while 12,068 (28.19 %) unigenes were not similar to any known protein in the five databases. Among the five databases, the nr database produced the largest number of annotations; of the 30,748 annotated unigenes, 30628 (99.6 %) were annotated in the nr database. In comparison with other species, O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes showed the highest similarity with sequences from Solanum lycopersicum (7211) and Vitis vinifera (4514), but also were similar to sequences from other species (Fig. 3 and Additional file 2: Table S2).

Table 3.

Annotation statistics of O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes

| Database | Unigene number | Number of DEGs |

|---|---|---|

| Nr | 30,628 | 4457 |

| Swisprot | 24,531 | 3700 |

| KEGG | 8533 | 1399 |

| Gene Ontology | 10,172 | 1450 |

| COG | 28,853 | 4261 |

| Total | 30,748 | 4465 |

Fig. 3.

Similarity of O. americanum var. pilosum sequences with those of other species

We performed a GO analysis to classify the functions of the O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes. A total of 10172 unigenes were successfully annotated with GO terms and were classified into three major GO categories: Biological Processes (BP), Cell Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF). They were further assigned to 51 subcategories based on GO level 2. The dominant subcategories for the classified genes were ‘cell’ (93.1 %) and ‘cell part’ (93.1 %) for the CC category; ‘cellular process’ (82.6 %), ‘metabolic process’ (78.8 %), and ‘response to stimulus’ (44.7 %) for the BP category; and ‘binding’ (60.4 %), ‘catalytic activity’ (54.9 %), and ‘transporter activity’ (9.5 %) for the MF category (Fig. 4). To identify active biochemical pathways in O. americanum var. pilosum, KEGG analysis was carried out; KEGG-annotated unigenes (8533) were classified to 273 pathways (>10 associated unigenes) (Additional file 3: Table S3). Among these pathways, the five most represented were “Carbon metabolism”, “Biosynthesis of amino acids”, “Ribosome”, “Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum”, and “Plant-pathogen interaction” (Additional file 4: Figure S1).

Fig. 4.

Histogram of GO (gene ontology) classifications of assembled unigenes and up- and down-regulated unigenes of O. americanum var. pilosum in response to low temperature

In summary, all these annotation and classification analyses can provide valuable information to further investigate gene functions, metabolic processes, and active pathways of O. americanum var. pilosum.

Differentially expressed genes in chilling-treated O. americanum var. pilosum plants

Using our de novo assembled transcriptome as a reference, we identified putative genes expressed in control and chilling-treated plants. In control_rep1 and control_rep2 samples, 40,372 and 40,407 expressed putative genes (FPKM > =1) were detected, and 39334 were expressed in both samples. In chilling_rep1 and chilling_rep2 samples, 40,004 and 40,043 expressed putative genes (FPKM > =1) were detected, and 39,028 were expressed in both samples. The high similarity between the two biological replicates for either control or chilling-treated samples indicated that the RNA-seq results were consistent. The consistency was also supported by FPKM (fragments per kilobase of gene per million mapped reads) correlation analysis between the two biological replicates (r > 0.99) (Additional file 5: Figure S2).

To begin to explore the molecular mechanisms of cold stress response of O. americanum var. pilosum, we identified genes that were differentially expressed in seedlings grown under normal vs. chilling temperatures. Compared with the control, 5,179 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with at least 2-fold changes (false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.01) were identified in chilling-treated samples with the edgeR package. Of these DEGs, 2,344 were up-regulated and 2,835 were down-regulated in chilling-treated plants. Functional annotation with five databases was also executed on these DEGs, and about 86 % of them (4,465 DEGs) were successfully annotated (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S1).

About 608 up-regulated DEGs and 842 down-regulated DEGs were successfully annotated with GO (Table 3 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Their GO level 2 distributions are shown in Fig. 4. Up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs had a similar distribution pattern, which was also similar to that of all GO annotated unigenes (Fig. 4).

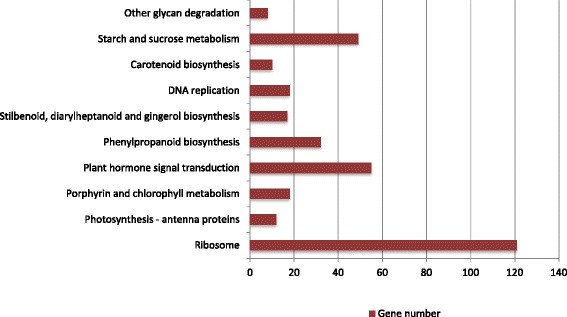

To better understand the biological function and correlation of these DEGs, we conducted an enrichment analysis with the KEGG pathway, which assigned the DEGs to 10 pathways (Fig. 5). Among these pathways, “Ribosome”, “Plant hormone signal transduction”, “Starch and sucrose metabolism”, and “Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis” were the most highly represented (Table 4). The “Ribosome” pathway (ko03010) had the largest number of DEGs, suggesting that translation in O. americanum var. pilosum is substantially influenced by low temperature. The pathway with the second largest number of DEGs was “Plant hormone signal transduction” (ko04075), indicating that plant hormones in O. americanum var. pilosum play important roles in the response to chilling stress. Sucrose and starch metabolism (ko00500) was the pathway with the third largest number of DEGs; this was not surprising because chilling affects carbon assimilation and sucrose contributes to chilling tolerance by stabilizing plasma membranes [23]. Ocimum spp. are commonly used as spices and as sources of essential oils because these plants synthesize large quantities of phenylpropanoid compounds [24]. Interestingly, the pathway with the fourth largest number of DEGs was “Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis” (ko00940), suggesting that the composition of aromatic compounds may change under cold stress.

Fig. 5.

KEGG pathway classification of differentially expressed unigenes of O. americanum var. pilosum

Table 4.

KEGG pathway enrichment of DEGs

| Pathway ID | Description | P-value | Gene number |

|---|---|---|---|

| ko03010 | Ribosome | 2.30E-25 | 121 |

| ko04075 | Plant hormone signal transduction | 6.31E-04 | 55 |

| ko00500 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 4.88E-03 | 49 |

| ko00940 | Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis | 7.59E-04 | 32 |

| ko00860 | Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism | 4.01E-04 | 18 |

| ko03030 | DNA replication | 3.25E-03 | 18 |

| ko00945 | Stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis | 2.08E-03 | 17 |

| ko00196 | Photosynthesis - antenna proteins | 3.66E-08 | 12 |

| ko00906 | Carotenoid biosynthesis | 3.86E-03 | 10 |

| ko00511 | Other glycan degradation | 8.91E-03 | 8 |

In general, analyses towards DEGs in response to cold will help to understand how gene expression in O. americanum var. pilosum is influenced by chilling treatment.

Validation of DEGs in chilling-treated O. americanum var. pilosum plants

We checked the functional annotations of those DEGs that exhibited the greatest difference in expression in response to chilling treatment. The 10 most up- and down-regulated genes and their annotations are listed in Table 5. Ob_12222, a putative ortholog of PID-binding protein 1 (PBP1) in Arabidopsis, was the gene that was most induced by chilling treatment. This indicates an interplay between auxin signaling and cold response in O. americanum var. pilosum because PBP1 is related to auxin signaling. More specifically, PBPI can stimulate the autophosphorylation activity of PID (PINOID) protein serine/threonine kinase, which is a key component in auxin signaling [25], and auxin plays an important role in cold stress inhibition of plant growth and development [26]. To validate our RNA sequencing results, we performed individual qRT-PCR to examine the expression of the 10 most up-regulated genes and the five most down-regulated genes after chilling for 0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h. All 10 up-regulated genes were well induced by chilling, although their expression changed with the length of the chilling treatment (Fig. 6a). Consistent with the RNA-seq results, all five of the most down-regulated genes were repressed by chilling (Fig. 6b). The consistency between qRT-PCR results and RNA-seq analyses helps confirm the validity of our de novo assembled transcriptome and our analysis of cold stress regulation of the transcriptome.

Table 5.

The 10 most up- and down-regulated O. americanum var. pilosum genes after cold treatment

| Unigene ID | Type | Log2 (fold-change) | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ob_12222 | up | 8.01 | PBP1 | Calcium-binding protein PBP1 |

| Ob_33171 | up | 6.82 | At2g40140 | Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 29 |

| Ob_05225 | up | 6.54 | NA | NA |

| Ob_13772 | up | 6.41 | LIR1 | Light-regulated protein |

| Ob_31535 | up | 6.32 | NA | Brassinosteroid-regulated protein BRU1 |

| Ob_26551 | up | 6.23 | WRKY53 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 53 |

| Ob_30260 | up | 5.53 | MYC4 | Transcription factor MYC4 |

| Ob_28998 | up | 5.36 | BBD2 | Bifunctional nuclease 2 |

| Ob_21755 | up | 5.36 | NA | NA |

| Ob_32844 | up | 5.36 | RVE1 | Protein REVEILLE 1 |

| Ob_13881 | down | −6.97 | NA | NA |

| Ob_33671 | down | −6.50 | CYP71A8 | Cytochrome P450 71A8 |

| Ob_20246 | down | −5.72 | CAB36 | Chlorophyll a-b binding protein 36, chloroplastic |

| Ob_24578 | down | −5.59 | CDF3 | Cyclic dof factor 3 |

| Ob_26837 | down | −5.47 | COL5 | Zinc finger protein CONSTANS-LIKE 5 |

| Ob_36212 | down | −5.43 | WAXY | Granule-bound starch synthase 1, chloroplastic/amyloplastic |

| Ob_38127 | down | −5.27 | NA | Retrovirus-related Pol polyprotein from transposon TNT 1-94 |

| Ob_34404 | down | −5.15 | DSPP | Dentin sialophosphoprotein |

| Ob_20836 | down | −4.97 | SAT1 | Serine acetyltransferase 1, chloroplastic |

| Ob_27478 | down | −4.96 | UGT83A1 | UDP-glycosyltransferase 83A1 |

Fig. 6.

The expression of O. americanum var. pilosum genes in response to chilling at 4 °C for 0 to 48 h as determined by qRT-PCR. a Expression of the 10 most up-regulated genes. b Expression of the five most down-regulated genes

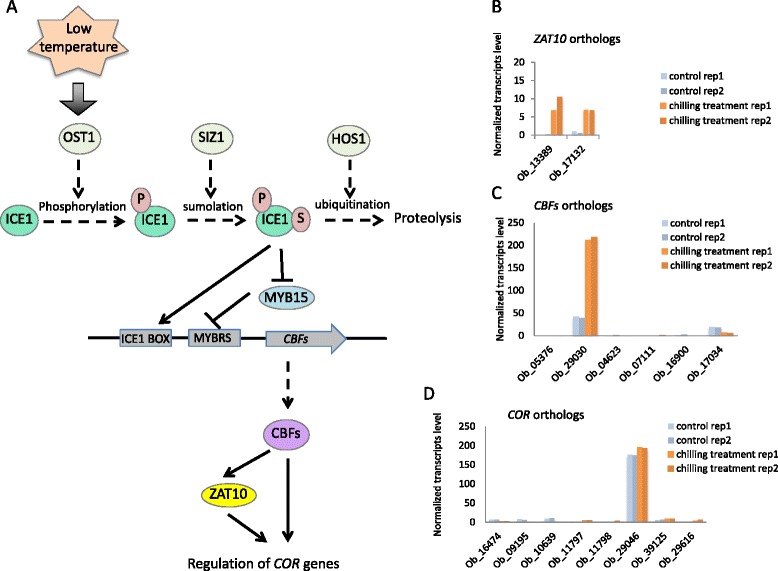

O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes involved in the CBF cold response pathway

The CBF transcriptional cascade is an important pathway for the regulation of gene expression under low temperature in diverse plant species. Using our RNA-seq data for O. americanum var. pilosum and Blastx, we identified CBF-pathway genes with the following parameters: an expectation value of 1e-5, an identity value > 30 %, a coverage value > 80 %, and a protein length difference < 2x. A total of 39 unigenes were identified as putative orthologs of genes in the CBF pathway, and their corresponding CBF-pathway orthologs are listed in Table 6. In O. americanum var. pilosum, Ob_28165 and Ob_11817 were found to be similar to ICE1, which can be modified by phosphorylation and sumolation when plants are exposed to low temperature. The enzyme responsible for ICE1 sumoylation, SIZ1, has four similar unigenes: Ob_17220, Ob_17219, Ob_35232, and Ob_03308. The modified ICE1 can activate CBF transcription and repress the CBF transcription inhibitor, MYB15. In our assembled transcriptome, 10 unigenes (Ob_36284, Ob_07479, Ob_16876, Ob_32681, Ob_06567, Ob_08721, Ob_09654, Ob_08732, Ob_15732, and Ob_38631) with high similarity to the MYB15 sequence were identified, and six unigenes (Ob_05376, Ob_29030, Ob_04623, Ob_07111, Ob_16900, and Ob_17034) were matched to known CBF gene sequences (Table 6). The degradation of ICE1 can be facilitated by ubiquitination by HOS1, and thus HOS1 negatively regulates CBF expression. One unigene, Ob_33354, had high similarity with HOS1. CBFs can regulate the cold induction of ZAT10, a transcription factor involved in regulating the expression of a subset of cold-responsive genes (8). Two putative ZAT10 orthologs were found in O. americanum var. pilosum: Ob_13389 and Ob_17132. Sequences of the following eight expressed unigenes were similar to those of known COR genes, including COR15A, COR47, and KIN1: Ob_16474, Ob_09195, Ob_10639, Ob_11797, Ob_11798, Ob_29046, Ob_39125, and Ob_29616.

Table 6.

Unigenes matched to known CBF-pathway factors

| Unigene | Ortholog | Identity (%) | E-value | Control_rep1 | Control_rep2 | Chilling_rep1 | Chilling_rep2 | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ob_28165 | ICE1 | 32.39 | 7E-23 | 3.99 | 2.77 | 1.69 | 1.5 | Camellia sinensis |

| Ob_11817 | ICE1 | 43.3 | 9E-42 | 3.44 | 3.82 | 0.47 | 0.23 | Ageratina adenophora |

| Ob_17220 | SIZ1 | 71.95 | 8E-87 | 3.35 | 3.29 | 4.19 | 5.16 | Medicago truncatula |

| Ob_17219 | SIZ1 | 69.74 | 6E-95 | 10.61 | 11.98 | 12.85 | 12.44 | Medicago truncatula |

| Ob_35232 | SIZ1 | 46.97 | 0 | 20.28 | 19.72 | 26.04 | 25.37 | Triticum urartu |

| Ob_03308 | SIZ1 | 41.07 | 1E-31 | 1.03 | 1.77 | 1.05 | 1.03 | Medicago truncatula |

| Ob_36284 | MYB15 | 37.16 | 7E-27 | 19.67 | 19.83 | 24.17 | 22.48 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_07479 | MYB15 | 45.26 | 4E-23 | 0 | 0 | 6.01 | 5.56 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_16876 | MYB15 | 83.81 | 5E-67 | 1.67 | 1.31 | 2.03 | 1.33 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_32681 | MYB15 | 52.71 | 7E-41 | 14.13 | 14.66 | 19.59 | 19.57 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_06567 | MYB15 | 54.26 | 1E-45 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.34 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_08721 | MYB15 | 42.11 | 3E-32 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 3.97 | 4.7 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_09654 | MYB15 | 51.72 | 1E-37 | 0 | 0 | 0.92 | 0.9 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_08732 | MYB15 | 56.76 | 2E-42 | 2.21 | 1.45 | 3.37 | 3.32 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_15732 | MYB15 | 59.43 | 1E-44 | 1.33 | 1.31 | 1.01 | 1 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_38631 | MYB15 | 66.3 | 5E-42 | 1.24 | 0 | 0.42 | 1.65 | Oryza sativa |

| Ob_33354 | HOS1 | 58.51 | 4E-87 | 54.04 | 52.4 | 61.79 | 59.4 | Medicago truncatula |

| Ob_05376 | CBF1 | 33.33 | 5E-11 | 0 | 0 | 0.38 | 0.37 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_29030 | CBF1 | 34.02 | 2E-11 | 42.71 | 39.55 | 211.72 | 218.64 | Solanum lycopersicum |

| Ob_04623 | CBF2 | 52.38 | 3E-29 | 1.12 | 1.84 | 0.38 | 0.75 | Solanum lycopersicum |

| Ob_07111 | CBF2 | 75 | 9E-54 | 0 | 0 | 0.72 | 1.42 | Solanum lycopersicum |

| Ob_16900 | CBF3 | 36.78 | 4E-08 | 1.66 | 2.86 | 0 | 0 |

Hordeum vulgare

subsp. vulgare |

| Ob_17034 | CBF3 | 38.85 | 1E-14 | 19.73 | 18.92 | 7.1 | 5.45 |

Hordeum vulgare

subsp. vulgare |

| Ob_13389 | ZAT10 | 54.24 | 2E-33 | 0 | 0.31 | 6.79 | 10.51 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_17132 | ZAT10 | 35.11 | 3E-12 | 1.09 | 0.59 | 7.01 | 6.79 | Cicer arietinum |

| Ob_16474 | COR15A | 39.51 | 5E-6 | 7.71 | 7.45 | 2.73 | 2.69 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_09195 | COR47 | 41.67 | 1E-09 | 8.34 | 6.96 | 0.38 | 0.62 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_10639 | COR47 | 40.41 | 5E-27 | 9.95 | 11.87 | 1.63 | 1.78 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_11797 | COR47 | 41.27 | 8E-18 | 2.07 | 1.69 | 4.55 | 4.48 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_11798 | COR47 | 46.07 | 3E-14 | 1.12 | 0.74 | 1.9 | 3.75 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_29046 | COR47 | 40.09 | 8E-32 | 177.38 | 175.3 | 195.61 | 192.62 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_39125 | COR47 | 42.64 | 3E-18 | 6.42 | 7.32 | 8.61 | 9 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

| Ob_29616 | KIN1 | 37.88 | 6E-11 | 1.85 | 2.43 | 4.39 | 5.87 | Arabidopsis thaliana |

For unigenes with similarity to CBF-pathway factors, normalized transcript levels in control and chilling-treated samples are shown in Fig. 7. When >2-fold change was used as a cutoff, two putative ICE1 orthologs (Ob_28165 and Ob_11817) and one putative CBF3 ortholog (Ob_17034) were slightly down-regulated, while one putative CBF1 ortholog (Ob_29030) and two putative ZAT10 orthologs (Ob_13389 and Ob_17132) were up-regulated after chilling treatment. Ob_29030 (similar to CBF1) was dramatically induced by chilling treatment (Additional file 7: Figure S3. and Fig. 7), while transcript levels of all the other putative CBF orthologs were very low. CBF can activate ZAT10 (8). Consistent with the induced expression of the putative CBF ortholog (Ob_29030), the expression of two putative ZAT10 orthologs (Ob_13389 and Ob_17132) was increased in response to chilling treatment. The transcript levels of the two putative ICE1 orthologs were reduced to different degrees after chilling treatment, although they both were expressed at low levels in control samples. Among the 10 putative MYB15 orthologs, transcript levels for two (Ob_07479 and Ob_08721) were slightly increased by chilling treatment (Additional file 7: Figure S3), and this increase might be explained by the decreased expression of its negative regulators, putative ICE1 orthologs. One putative CBF3 ortholog (Ob_17034), as a possible target of putative ICE1 and MYB15 orthologs, was slightly repressed by chilling treatment. Transcript levels of putative SIZ1 and HOS1 orthologs did not change in response to chilling treatment (Additional file 7: Figure S3). Interestingly, none of the identified COR orthologs in O. americanum var. pilosum was substantially induced by chilling treatment (Fig.7d).

Fig. 7.

Reconstruction of the CBF pathway in O. americanum var. pilosum and the relative expression of 16 unigenes putatively involved in the CBF signaling pathway in response to control and chilling treatment. a Diagram showing CBF pathway. b–d Relative expression of ZAT10, CBF, and COR orthologues in control and chilling treatment. For b–d, the results of two biological replicates are shown

Conclusions

O. americanum var. pilosum is an aromatic plant and a popular vegetable in central and southern parts of China. It is very sensitive to low temperatures. Here, we performed de novo transcriptome assembly of O. americanum var. pilosum using the Trinity program and obtained 42,816 assembled unigenes. By analyzing the genome-wide transcriptome under low temperature, we identified several thousand potential cold-responsive unigenes and 10 pathways containing DEGs under chilling treatment. Our analysis of the DEGs suggested that cold temperature significantly affects protein translation and cellular metabolism in this chilling sensitive species. Although most genes involved in the ICE1-CBF-COR pathway have orthologs in O. americanum var. pilosum, none of the identified orthologs of COR genes was induced by low temperature, which is consistent with the lack of cold tolerance in this plant. In summary, we have profiled the high-resolution expression pattern of O. americanum var. pilosum under normal and chilling conditions. Our results should be useful for future research concerning the molecular mechanisms of low temperature responses in O. americanum var. pilosum.

Methods

Plant materials

Seeds of O. americanum var. pilosum in this study were collected from Funan County of Anhui Province, China. Seeds germinated on MS agar medium. Then 5-day old seedlings were transferred to soil and grown in a growth room with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod at 22 °C. Chilling treatment were performed in climate chamber with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod at 4 °C. During chilling treatment, control plants were kept in the same conditions but at normal temperature (22 °C). RNA from 30-day-old plants was used in RNA-seq. For RT-PCR, young leaves of 6 individual one-month-old plants were collected at every indicated time points and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen before RNA extraction. Plants used for RT-PCR and RNA-seq were harvested in two independent experiments. Biological replicates in RNA-seq were harvested at the same time.

RNA sequencing and de novo transcriptome assembly

Total RNA was extracted from leaves of control and chilling (4 °C for 12 h) treated 30-day-old plants with the RNApure High-purity Total RNA Rapid Extraction Kit (Bioteke). Each treatment (± chilling) was represented by two biological replicates. Residual genomic DNA was removed from the total RNA with the Turbo DNA-Free kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer's instructions. The sequencing library construction and sequencing were performed in the Genomics Core Facilities of the Shanghai Center for Plant Stress Biology, SIBS, CAS (Shanghai, China) with Illumina HiSeq2500. Clean reads were acquired from initial paired-end reads after low quality regions (Q <20), PCR duplicates, and adaptor sequences were trimmed.

Inchworm, Chrysalis, and Butterfly modules of Trinity software [15, 20] were used for de novo transcriptome assembly. We first combined the sequencing reads from the four samples and applied Inchworm to assemble the RNA-seq data into contigs (unique sequences of transcripts) with the default K-mer parameter and minimum K-mers coverage of three. The resulting Inchworm contigs were bunched by Chrysalis into clusters; Chrysalis was then used to constructed complete de Bruijn graphs for each cluster. Finally, the final assembled transcripts for alternatively spliced isoforms were reconstructed by Butterfly by reconciling individual deBruijn graphs, and only transcripts ≥ 300 bp long were retained for further analysis.

Annotation of O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes

Unigenes were first annotated by using BLASTX with an expectation value of 10−5 to search the following protein databases: NCBI nr protein database (NCBI non-redundant sequence database), SwissProt, and KEGG. Next, protein information and their functional annotations were retrieved for genes with the highest sequence similarity with O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes.

Identification and annotation of DEGs

DEGs were identified based on the negative binomial distribution with the edgeR package [27]. We calculated the false discovery rate (FDR) values of genes firstly through edgeR, and mapped reads numbers of genes were used in this analysis. Genes with FDR ≤0.01 were considered as candidates. In addition, fragments per kilobase of gene per million mapped reads (FPKM) of these candidates was generated by using RSEM [28]. Finally, the fold change of FPKM was computed, and genes with the over or equal to 2-fold change were characterized as DEGs. Functional enrichment analyses were then performed on identified DEGs by using GOstats [29]. For Gene Ontology and KEGG pathway analysis, we used Hypergeometric test function (p value < 0.001) [30].

qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression

With the RNApure High-purity Total RNA Rapid Extraction Kit (Bioteke), total RNA was extracted from leaves of 1-month-old plants treated at 4 °C for 0, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h. Residual genomic DNA was removed from the total RNA with the Turbo DNA-Free kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer's instructions. The first-strand cDNAs were synthesized from total RNA with the SupermoIII M-MuLV RT Kit (Bioteke) and were used as templates. A CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) was used for real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) with TransStart Tip Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech) to confirm the identity of up- or down-regulated genes. Each experiment had three biological replicates, and the PCR conditions were as follows: 40 cycle of 95 °C for 3 min, 95 °C for 10 s, and 58 °C for 30 s. The DNA primers for probe amplification are listed in Additional file 6: Table S4. The comparative cycle threshold (ct) method was used to calculate gene expression levels, and the TUBULIN ortholog Ob_23367 was used as reference.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are available in the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE68980).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The funders of this study played no role in the design, the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional files

List of annotated unigenes and lists of up-regulated genes and down-regulated genes in chilling-treated samples. (XLS 14564 kb).

Similarities between O. americanum var. pilosum and other species. (XLS 70 kb).

Pathways annotated by KEGG analysis. (XLS 221 kb).

The assignment of O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes to KEGG biochemical pathways. (PDF 114 kb)

Similarity analysis between two biological replicates of control and chilling-treated samples. (A) Correlation of the RNA-sequencing data between two biological replicates of control samples, between two biological replicates of chilling-treated samples, and between control samples and chilling-treated samples of O. americanum var. pilosum. (B) PCA analysis was performed to show similarity among different RNA-sequencing data. (PDF 104 kb)

Primer information. (XLSX 38 kb).

The relative expression of 17 O. americanum var. pilosum unigenes involved in the CBF pathway in untreated plants (grey bars) and in chilling-treated plants (orange bars). Values for two biological replicates are shown. (PDF 176 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

XZ, J-KZ, and ZL designed the study, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. XZ performed experimental work. LY and ZL did the bioinformatics analysis. XZ, LY, DW, J-KZ and ZL, contributed to the experiments and discussion of results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jian Kang Zhu, Email: jkzhu@purdue.edu.

Zhaobo Lang, Email: zblang@sibs.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Yamada AN, Grespan R, Yamada ÁT, Silva EL, Silva-Filho SE, Damião MJ, de Oliveira Dalalio MM, Bersani-Amado CA, Cuman RKN. Anti-inflammatory activity of Ocimum americanum L. essential oil in experimental model of zymosan-induced arthritis. Am J Chin Med. 2013;41(4):913–926. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X13500614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayala B, Bassole IHN, Gnoula C, Nebie R, Yonli A, Morel L, Figueredo G, Nikiema J-B, Lobaccaro JMA, Simpore J. Chemical composition, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative activities of essential oils of plants from burkina faso. PLoS One. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thaweboon S, Thaweboon B. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Ocimum americanum L. essential oil against oral microorganisms. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(5):1025–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalcanti ESB, de Morais SM, Lima MAA, Santana EWP. Larvicidal activity of essential oils from Brazilian plants against Aedes aegypti L. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99(5):541–544. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762004000500015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upadhyay AK, Chacko AR, Gandhimathi A, Ghosh P, Harini K, Joseph AP, Joshi AG, Karpe SD, Kaushik S, Kuravadi N, Lingu CS, Mahita J, Malarini R, Malhotra S, Malini M, Mathew OK, Mutt E, Naika M, Nitish S, Pasha SN, Raghavender US, Rajamani A, Shilpa S, Shingate PN, Singh HR, Sukhwal A, Sunitha MS, Sumathi M, Ramaswamy S, Gowda M, et al. Genome sequencing of herb Tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) unravels key genes behind its strong medicinal properties. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:212. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0562-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rastogi S, Meena S, Bhattacharya A, Ghosh S, Shukla RK, Sangwan NS, Lal RK, Gupta MM, Lavania UC, Gupta V, Nagegowda DA, Shasany AK. De novo sequencing and comparative analysis of holy and sweet basil transcriptomes. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:588. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu J, Dong CH, Zhu JK. Interplay between cold-responsive gene regulation, metabolism and RNA processing during plant cold acclimation. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10(3):290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chinnusamy V, Zhu J, Zhu JK. Cold stress regulation of gene expression in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12(10):444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilmour SJ, Zarka DG, Stockinger EJ, Salazar MP, Houghton JM, Thomashow MF. Low temperature regulation of the Arabidopsis CBF family of AP2 transcriptional activators as an early step in cold-induced COR gene expression. Plant J. 1998;16(4):433–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinnusamy V, Ohta M, Kanrar S, Lee BH, Hong X, Agarwal M, Zhu JK. ICE1: a regulator of cold-induced transcriptome and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2003;17(8):1043–1054. doi: 10.1101/gad.1077503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao C, Lang Z, Zhu JK. Cold responsive gene transcription becomes more complex. Trends Plant Sci. 2015;20(8):466–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding Y, Li H, Zhang X, Xie Q, Gong Z, Yang S. OST1 Kinase Modulates Freezing Tolerance by Enhancing ICE1 Stability in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell. 2015;32(3):278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miura K, Jin JB, Lee J, Yoo CY, Stirm V, Miura T, Ashworth EN, Bressan RA, Yun DJ, Hasegawa PM. SIZ1-mediated sumoylation of ICE1 controls CBF3/DREB1A expression and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19(4):1403–1414. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong CH, Agarwal M, Zhang Y, Xie Q, Zhu JK. The negative regulator of plant cold responses, HOS1, is a RING E3 ligase that mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of ICE1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(21):8281–8286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602874103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mousavi S, Alisoltani A, Shiran B, Fallahi H, Ebrahimie E, Imani A, Houshmand S. De novo transcriptome assembly and comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes in Prunus dulcis Mill. in response to freezing stress. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moliterni VMC, Paris R, Onofri C, Orrù L, Cattivelli L, Pacifico D, Avanzato C, Ferrarini A, Delledonne M, Mandolino G. Early transcriptional changes in Beta vulgaris in response to low temperature. Planta. 2015;242(1):187–201. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2299-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang M, Zhang X, Liu JH. Deep sequencing-based characterization of transcriptome of trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.) in response to cold stress. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:555. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1629-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Jiang Y, Lan J, Zou Y, Gao J. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of the response to cold acclimation in Eucalyptus dunnii. PLoS One. 2014;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren L, Sun J, Chen S, Gao J, Dong B, Liu Y, Xia X, Wang Y, Liao Y, Teng N, Fang W, Guan Z, Chen F, Jiang J. A transcriptomic analysis of Chrysanthemum nankingense provides insights into the basis of low temperature tolerance. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:844. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Yang Y, Liu X, Huang J, Wang Q, Gu J, Lu Y. Transcriptome profiling of the cold response and signaling pathways in Lilium lancifolium. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:203. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villacorta-Martin C, Núñez de Cáceres González FF, de Haan J, Huijben K, Passarinho P, Lugassi-Ben Hamo M, Zaccai M. Whole transcriptome profiling of the vernalization process in Lilium longiflorum (cultivar White Heaven) bulbs. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:550. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1675-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, Amit I, Adiconis X, Fan L, Raychowdhury R, Zeng Q, Chen Z, Mauceli E, Hacohen N, Gnirke A, Rhind N, di Palma F, Birren BW, Nusbaum C, Lindblad-Toh K, Friedman N, Regev A. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valluru R, Van den Ende W. Plant fructans in stress environments: emerging concepts and future prospects. J Exp Bot. 2008;59(11):2905–2916. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gang DR, Wang J, Dudareva N, Nam KH, Simon JE, Lewinsohn E, Pichersky E. An investigation of the storage and biosynthesis of phenylpropenes in sweet basil. Plant Physiol. 2001;125(2):539–555. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamins R, Ampudia CSG, Hooykaas PJJ, Offringa R. PINOID-mediated signaling involves calcium-binding proteins. Plant Physiol. 2003;132(3):1623–1630. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahman A. Auxin: a regulator of cold stress response. Physiol Plant. 2013;147(1):28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beissbarth T, Speed TP. GOstat: find statistically overrepresented Gene Ontologies within a group of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(9):1464–1465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]