Abstract

In vitro motility assays enabled the analysis of coupling between ATP hydrolysis and movement of myosin along actin filaments or kinesin along microtubules. Single-molecule assays using laser trapping have been used to obtain more detailed information about kinesins, myosins, and processive DNA enzymes. The combination of in vitro motility assays with laser-trap measurements has revealed detailed dynamic structural changes associated with the ATPase cycle. This article describes the use of optical traps to study processive and nonprocessive molecular motor proteins, focusing on the design of the instrument and the assays to characterize motility.

BACKGROUND

Development of quantitative in vitro motility assays for myosin movement along actin filaments (Sheetz and Spudich 1983; Spudich et al. 1985; Kron and Spudich 1986) and kinesin movement along microtubules (Vale et al. 1985; Gelles et al. 1988) allowed direct analyses of the coupling between ATP hydrolysis and mechanical movement of these molecular motors. In vitro motility assays provide a direct measure of velocity with purified proteins, as well as information on the directionality of movement of motors along their tracks, which have a polarity inherent to their structure. These assays provided early insights into the step size of myosin II and allowed the definition of subfragment-1 of myosin II as the motor domain (Toyoshima et al. 1987). Importantly, in vitro motility assays also generated the first single-molecule observations for movement of kinesin on a microtubule (Howard et al. 1989) and of myosin on an actin filament (Uyeda et al. 1991).

The relatively straightforward conceptual modifications of the in vitro motility assays to a single-molecule assay using laser trapping (Svoboda et al. 1993; Finer et al. 1994; Visscher et al. 1999) (e.g., Fig. 1, left) has allowed much more sophisticated information to be obtained, such as the step sizes of actively walking motors, the kinetics of the ATPase cycle, stall forces, and the effects of load on the motor molecule's biochemical and mechanical behavior. Kinesins (Svoboda et al. 1993; Visscher et al. 1999), myosins (Finer et al. 1994; Mehta et al. 1999c; Rief et al. 2000; Rock et al. 2001), and processive DNA enzymes (Wang et al. 1998; for review, see Mehta and Spudich 1998) have all been studied using this powerful tool. Information from optical trap experiments places constraints on models for the mechanisms of these molecular motors and has led to a greatly increased understanding of how they work.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic illustrations of in vitro assays and myosin VI. (Left) Illustrations of an in vitro motility assay (Kron and Spudich 1986) (above) and a single-molecule laser-trap assay (Finer et al. 1994) derived from it (below). In both cases, myosin is coated on a glass coverslip and fluorescent actin filaments move on the myosin molecules. For the laser-trap assay, platforms (~1-μm glass beads) are adhered to the coverslip to elevate single myosin molecules for interaction with actin that is held in suspension with dual-laser traps, each holding a 1-μm polystyrene bead attached to the end of the actin filament. (Right) Illustration of the prestroke state of myosin VI derived from in vitro motility and laser-trap single-molecule analyses (Bryant et al. 2007) and the known poststroke structure of myosin VI (Ménétrey et al. 2005). The (−) end directionality of the motor is clearly derived from the unique insert and its bound calmodulin (orange and purple regions), an element of the lever arm not present in myosins II and V. Going from the prestroke state to the poststroke state, the carboxy-terminal end of the lever arm (blue) moves in the (−) end direction of the actin filament (to the right), whereas the converter domain (green) moves in the (+) end direction, like myosins II and V.

Particularly powerful is the combination of in vitro motility assays with laser-trap measurements to reveal detailed dynamic structural changes associated with the ATPase cycle. A vivid example is a recent study on myosin VI, an unusual myosin that takes very long (~36-nm) steps despite having a very short light-chain-binding domain that in other myosins almost certainly acts as a lever arm to amplify mechanical movement. The apparent discrepancy between its step size and length of its light-chain-binding domain has made myosin VI the most serious challenge to the lever-arm hypothesis (Yanagida and Iwane 2000). By mapping the step sizes using the laser trap and the velocities and direction of movement of four different constructs of myosin VI onto the known poststroke structure of the motor (Ménétrey et al. 2005), the general features of the prestroke structure have been functionally revealed (Fig. 1, right) (Bryant et al. 2007). The results obtained indeed point to a lever-arm mechanism for myosin VI, but in this case, the short lever arm strokes through an angle of ~180° to give rise to a large mechanical stroke of ~20 nm, the remaining ~16 nm deriving from diffusion of the free head in search of the appropriate actin-binding site. This study drives home the power of in vitro motility assays and single-molecule analysis to reveal detailed structural information about functionally important mechanical transitions in proteins and solidifies the swinging-lever-arm hypothesis as a general mechanism used by the myosin family.

For most laboratories, the drawbacks of optical trapping have been the high cost and difficulty of building, maintaining, and using the devices. However, all of the components for an extremely sensitive optical trap are now commercially available, and the prices of the major components continue to decrease. Improvements in optical trapping technology and assays have made the technique readily accessible, and the optical trap is becoming a standard microscope for studies of movement and force in biological systems. Here, we describe the use of optical traps to study processive and nonprocessive molecular motor proteins, focusing on the design of the instrument and the assays to characterize motility. The reader is also referred to a variety of other descriptions of optical trap design and use (Ashkin 1998; Mehta and Spudich 1998; Berns et al. 1992; Franklin et al. 1994; Svoboda and Block 1994; Simmons et al. 1996; Smith et al. 1996; Visscher et al. 1996; Mehta et al. 1997, 1998a,b, 1999a,b; Gittes and Schmidt 1998; Molloy 1998; Sheetz 1998; Sterba and Sheetz 1998; Visscher and Block 1998; Neuman et al. 1999, 2005; Rock et al. 2000; Schnitzer et al. 2000; Steffen et al. 2001; Rice et al. 2003; Neuman and Block 2004; Berg-Sorensen et al. 2006). Protocols are also available for Attachment of Anti-GFP Antibodies to Microspheres for Optical Trapping Experiments (Spudich et al. 2011a) and The Optical Trapping Dumbbell Assay for Nonprocessive Motors or Motors That Turn around Filaments (Spudich et al. 2011b).

OPTICAL TRAPPING INSTRUMENTATION

Basic Design of the Optical Trap

An optical trap consists of a laser that is strongly focused through a lens with a very short focal length (most often a high numerical aperture [NA] microscope objective). In an oversimplified view, laser light entering an object is refracted through it and, because of light's momentum, exerts forces on the object. For spherical objects, such as the beads used in this article, the laser draws the center of the object into its focus. Its force characteristics can be approximated as a linear spring in all directions. The spring constant is termed the trap stiffness, which is usually 0.02–0.06 pN/nm for the optical traps used to study molecular motors. Much stronger traps (up to 1 pN/nm) have also been designed (Smith et al. 1996). Moving cytoskeletal motors produce relatively weak forces, stalling at ~5 pN and taking step sizes of 5–40 nm. Thus, an optical trap for measuring single displacements of molecular motors should be designed to reliably detect single displacements on the order of nanometers with millisecond time resolution.

The design of the trap discussed here is shown in Figure 2. In our first design of a dual beam optical trap (Fig. 1, left), acousto-optic deflectors (AODs) performed feedback on the position of the trap, but mirror translations and separated beam paths were used for steering the traps (Finer et al. 1994). At the time of this writing, we use a single set of two commercially available orthogonal AODs to create multiple traps and to rapidly adjust their position in the sample plane (Finer et al. 1994; Visscher et al. 1996; Molloy 1998). By changing the input signal to the AODs, many functions of the trap (such as positioning, modulation of trap stiffness, making multiple traps, force clamping, and position clamping) can be quickly and easily controlled.

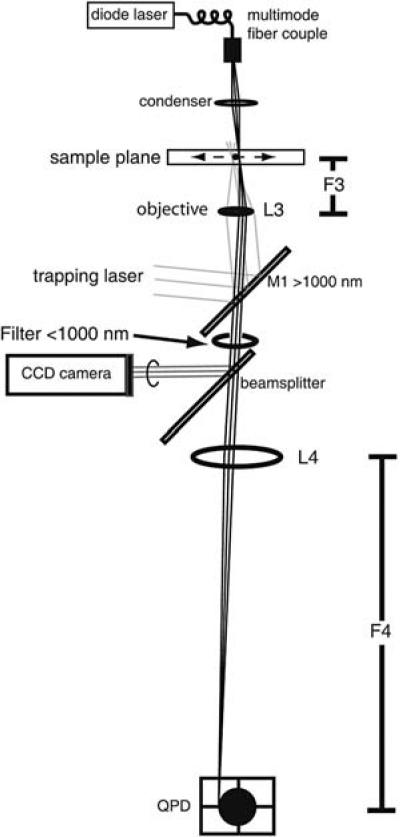

FIGURE 2.

Optical trap design. For the purposes of drawing ray optics of the laser light in this diagram, it is assumed that the lenses are thin. The Nd:YAG trapping laser (Coherent Compass 1064-2000) is shown on the left, and the laser beam emitting from it is shown as a black line. Most of the power is split off by the λ/2 waveplate (λ/2) and polarizing beam splitter (pol b/s) to a beam dump. After a threefold expansion, the beam is deflected by the orthogonal AODs. Only the original beam and one deflected beam are shown, although in reality four different major beams come out of the pair of AODs. The deflected beams are selected by an aperture at the focal length of lens L1 (described in text). Lenses L1 and L2 serve as a second threefold telescope, which expands the beam sufficiently to fill the back aperture of the objective lens (L3). The laser light is reflected up to the objective by a dichroic mirror (M1), which is also used to adjust the position and tilt of the optical trap in the sample plane for a coarse alignment. For the dual-beam trap shown in Figure 1 (left), there are two independent ray traces, only one of which is shown here. In that case, each trapping beam is independently governed by its own set of orthogonal AODs.

Details of Optical Trap Design

Nd:YAG, Nd:YVO4 (both 1064 nm) or Nd:YLF (1047 nm) trapping lasers are the most commonly used, because their ~1-μm wavelength minimizes photodamage to most biological samples (Berns et al. 1992; Svoboda and Block 1994; Neuman et al. 1999). These diode-pumped solid-state lasers have good pointing stability (for nanometer precision positioning) and high-power output levels (1–10 W). The Coherent Compass 1064–2000 CW laser used here is air-cooled and has an output of 2 W with a beam diameter of 1 mm.

To ensure good beam stability, the trapping laser must always be operated well above its lasing threshold. Its high-output power can damage some optics. The design shown in Figure 2 uses a polarizing beam splitter to divert some of the laser power into a beam dump. The polarization of the input light is controlled by rotating a λ/2 wave plate. A threefold beam expander (Newport T81-3X), placed after the polarizing beam splitter but before the AODs, expands the 1-mm diameter beam to 3 mm, which is close to the aperture size of the AODs (4-mm diameter). This gives the largest possible range of movement for the traps in the sample plane. After deflection by the AODs, the beam must be magnified to fill the back aperture of the objective lens (L3, Fig. 2). Deflections of the beam in the plane of L1 by the AODs are demagnified in the sample plane by a factor of F3/F2. The range of beam deflection by the AODs in the sample plane is maximized if the expansion of the beam after deflection by the AODs (F2/F1) is minimized. Unfortunately, this can cause fluctuations in the position of the trap because of noise being magnified to an unacceptable level in the sample plane. In practice, it is possible to achieve the maximal range of travel for the trap in the sample plane with an acceptable level of noise in the trap position.

In an AOD, a crystalline material is bonded to a piezoelectric transducer that converts a high-frequency oscillating voltage (MHz) into an acoustic wave that is propagated through the crystal and that has the same frequency as the applied voltage. As it travels through the crystal, it creates a standing wave pattern of compressions and expansions parallel to the transducer, resulting in periodic changes in the index of refraction of the crystal. These shift the phase of the incoming light. Deflection of the output beam is caused by diffraction off this phase grating. The acoustic wave, the periodicity of the grating, and the angle of deflection of the light are all changed by a change in the frequency of the applied voltage. The intensity profile of the diffraction pattern created by this grating depends on the incident angle of the laser light on the crystal. The AODs are positioned such that the first-order deflection through the grating has the maximum light intensity, whereas higher order deflections occur at large enough angles to be excluded from the light path with an aperture (to be discussed below). In practice, each of the AODs used in this design (IntraAction Corp.) deflects a maximum of ~75% of the incoming light in the first-order deflection. Some light remains undeflected and a small amount is deflected at higher orders. Thus, four zero- and first-order beams are emitted from the set of two orthogonally aligned (x and y) AODs: One that is undeflected, one that is deflected only in x, one that is deflected only in y, and one (maximally ~55% of the total incoming light) that is deflected in both x and y. The last is the selected trapping beam. Computer control of the AODs is discussed below.

After the AODs, two lenses expand the beam threefold to a total diameter of 9 mm, slightly overfilling the 7-mm-diameter back aperture of the objective lens. If the objective lens is underfilled, the incoming light does not focus as tightly. This causes lower trap stiffness in all directions, especially in the direction of laser beam propagation. The first lens (L1, Fig. 2) has a focal length of 50 mm. An aperture at the focal point selects the beam that is deflected to first order in both x and y. The maximum deflection angle in one direction in this design is ~50 mrad, with a range of 25 mrad. This translates into a 2.5-mm transverse distance in the focal plane of L1 between the centers of each of the four zero and first-order deflected beams. These will be four focused spots separated in position by at least 1.25 mm in either x or y. An aperture in the focal plane of L1 at the average travel position in both x and y accommodates the maximum range for first-order AOD deflections in both directions. At the same time, it eliminates the undeflected beam, the two beams deflected only in x and in y, and higher order deflections. The second lens, L2, is placed after the aperture by 150 mm (its focal length), such that the light is collimated after L2 and is then reflected up to the sample plane through a distance of 150 mm. If the separation between L2 and the focal plane of the objective lens is maintained, the objective lens is always back-filled, even as the beam is deflected by the AODs in the plane of L2. A dichroic mirror (M1) that reflects wavelengths >1000 nm reflects the laser light up to the sample plane.

The microscope objectives used in optical trapping usually have a high NA (≥1.2, and most often 1.4) to focus the trapping laser very sharply. The gradient of the trapping laser intensity as it goes through the bead determines the stiffness of the trap (Ashkin 1998).

Recording the Bead Position with Nanometer and Millisecond Resolution

The imaging system that records the bead position in the optical trap must be able to make nanometer precision measurements on millisecond or submillisecond timescales. Quadrant photodiode detectors (QPDs) have been used for this purpose because they are extremely sensitive to motion in two dimensions. In the method described in Figure 3, the trapped bead or beads are imaged onto QPDs (Hamamatsu, Inc.). There are other nonimaging methods for detecting bead position on QPDs in the back focal plane of the condenser (Svoboda et al. 1993; Visscher et al. 1996). The system described here uses a multimode fiber-coupled diode laser (800 nm, CW, 0.5 W from LaserDiode, Inc.) operated below its lasing threshold for bright-field illumination of the sample. Modern high-brightness light-emitting diodes (LEDs) would be a less expensive substitute. Light that refracts through the bead is deflected away from the QPD, leaving the image of a single dark silhouette corresponding to the bead position. For maximum resolution of the bead position, the diameter of this silhouette should be about the size of the QPD (1 mm, in the setup discussed here). A lens with a very long focal length (750 mm), L4 (Fig. 3), is used at a distance from the objective lens which gives about ×600 magnification on the QPD placed at its focal plane. In this setup, the QPD is sensitive to position changes of a centered 1-mm diameter image of ~1 μm. This translates to nanometer scale sensitivity to motions of the bead. Motion in two dimensions is detected by comparing the voltage response of four different photodiodes to incident light. The QPD outputs compare the voltage of the left two versus the right two quadrants ([1 + 3] – [2 + 4])/(1 + 2 + 3 + 4) and the top two versus the bottom two quadrants ([1 + 2] – [3 + 4])/(1 + 2 + 3 + 4). As a bead is moved from the center of the QPD to the right, the QPD output decreases linearly along with the left–right signal ([1 + 3] – [2 + 4])/(1 + 2 + 3 + 4). The QPD output does not change until the bead begins to leave the detector and the left–right signal begins to increase, bringing the QPD voltage response back up until it reaches zero. In practice, the useful range of the QPD can be extended somewhat by fitting the QPD response to a cubic or higher order odd polynomial.

FIGURE 3.

Tracking of bead movements on a QPD detector. A setup for imaging a 1-μm bead onto the QPD detector is shown. For simplicity, the figure is drawn assuming that lenses are thin. A diode laser at 800 nm (Laser Diode, Inc. LCW-200F, 500 mW output) coupled into a multiple mode fiber and pumped just below its lasing threshold is used for a high brightness light source introduced through the condenser. The image of the bead passes through the objective lens and the dichroic mirror (M1). A <1000-nm filter blocks out any trapping laser light that is back-reflected off the water-glass interface in the sample. A beam splitter diverts a small amount of the incoming light to the CCD camera for bright-field imaging. L4 magnifies the image of the bead onto the QPD, which is set up one focal length away from L4, for nanometer precision positioning of the trapped bead. In the dual-beam trap shown in Figure 1 (left), both actin-attached beads are independently imaged on two different QPDs. The trace shown here is simplified to illustrate one such imaging.

The voltage outputs from the QPDs are recorded by computer for later analysis. High-speed data acquisition (DAQ) cards are commonly available and can record bead position at sufficient time resolutions (tens of kHz). The recorded data can be viewed and analyzed by software packages such as LabView (National Instruments), Matlab (MathWorks), or Igor (WaveMetrics).

Unintended signal filtering can occur in the system described above (Berg-Sorensen et al. 2003). Flyvbjerg and colleagues (Berg-Sorensen et al. 2003, 2006; Berg-Sorensen and Flyvbjerg 2004) describe ways to circumvent this issue, which is less of a problem in more recent position-sensitive detectors (Neuman and Block 2004).

It is advantageous to use bright-field and fluorescence imaging simultaneously while the trap is being used. Many filaments used in optical trapping (i.e., actin, DNA) are not easily detected by light microscopy, necessitating fluorescence imaging. The proper choice of dichroic mirrors and placement of components allow the simultaneous use of a fluorescence light source, a bright-field source, cameras for both types of illumination, and the QPD, as described previously (Mehta et al. 1998a).

Coarse control of the x, y, and z positions of the microscope stage (usually with joystick-controlled motorized micrometers for x and y) is used to find and position samples in the optical trap. If extremely accurate positioning (~1 nm) is needed, a three-axis piezoelectric stage can be used. Feedback control mechanisms greatly decrease stage drift and measure the positions of system components with better than nanometer accuracy (Steffen et al. 2001).

Optical Trap Alignment

Laser alignment is achieved by placing a pinhole aperture in the beam path between the laser and the optic. The back reflection off the optic strikes the aperture and the lens is translated in x and y in the beam path until the back reflection forms a halo around the aperture opening. To center the optic precisely perpendicular to the laser, a second reflection of the laser off the front of the lens is brought to the center of the aperture by tilting the optic in the plane perpendicular to the table.

To ensure that the trap is located in the center of the field of view, the trap light entering the objective back pupil should be parallel to the objective optical axis. To achieve this, the objective is removed, and a mirror is placed flat on the shoulder of the objective mount. The trap light is then back-reflected with an upstream mirror mount.

A coarse optical trap alignment in the sample plane can be performed without an infrared viewer, using a bright-field charge-coupled device (CCD) camera to image the back reflection of the laser off the glass–water interface in a sample. Figure 4 illustrates the setup with a high-resolution Sony Iris CCD camera for bright-field visualization. As shown in Figure 3, a <1000-nm cutoff filter in the light path normally prevents the imaging of the small amount of light from the trapping laser on the CCD camera and QPD (Mehta et al. 1998a). For this alignment, however, the <1000-nm cutoff filter is removed and the bright-field light source is blocked. The camera is then sensitive to the small amount of trapping laser light back-reflected into it. The back-reflected image of the trap at the glass-water interface of the sample is in focus when the objective lens is focused near the coverslip surface. As the objective is moved up and down, this image goes into and out of focus. When the trap is properly aligned perpendicular to the back focal plane of the objective, the out-of-focus image centers around the trap's focal point. If the trap is significantly out of alignment, this image drifts at an angle to the trap's focal point as the objective is adjusted. The beam can be aligned by systematically adjusting any pair of optics (e.g., the ×3 telescope lenses L1 and L2) and by testing the alignment as above in a “walk-in” procedure (Sheetz 1998). Alternatively, a slide with an extremely high density of beads can be created (Sheetz 1998). The traps pull beads near the center in and push those just outside the trap away. A pattern that looks like a symmetric “ripple” is created if the trap is centered perpendicular to the sample plane. If the trap is skewed relative to the sample plane, beads appear to be pulled from one side of the field and pushed toward the other. Realignment is then performed as above. The trap stiffness and AODs must be recalibrated after alignment, because the optical path is affected by this procedure.

FIGURE 4.

Alignment of the optical trap. Shown is a schematic illustration of a setup that enables alignment of the trap in the sample plane using the CCD camera to image the back reflection of the trapping light off the glass–water interface. Because the cutoff of the dichroic mirror is 1000 nm, a small amount of the trapping laser light (1064 nm) is transmitted through it, and this is imaged onto the CCD camera at high sensitivity.

Calibration of AODs, QPD, and Trap Stiffness

Bead deflection by a given input frequency on the AODs, bead magnification on the QPD, and trap stiffness must all be computed before forces and step sizes of molecular motors can be measured in an optical trap. The calibration procedure described here has four steps.

Find the magnification of the video screen showing the image of the bead on the CCD camera by using a calibration slide (5- or 10-μm scale) to create a scale for the microscope on the video screen of the CCD camera.

Quantify the magnitude of beam deflection by the AODs in the sample plane by measuring distance deflected on the video screen versus AOD input signal.

Find the magnification of the bead on the QPD by deflecting the beam a known distance using the AOD and measuring the QPD response through its entire range.

Calibrate the trap stiffness. A number of methods are available (Visscher et al. 1996; Gittes and Schmidt 1998; Visscher and Block 1998), two of which are discussed here. They are complementary because the assumptions made by each method and the system parameters that they depend on are different. The first method measures the position variance of a trapped bead over a long period of time, whereas the second method fits the power spectrum of the Brownian motion of the bead over a wide range of frequencies.

Using the equipartition theorem, the variance of the bead position in one dimension in an optical trap over sufficiently long timescales is given by kbT/κ, where κ is the trap stiffness. Assuming that the trap behaves like a linear spring in any one dimension, this variance should depend only on the temperature of the sample. This generally holds for the x and y dimensions of the bead's movement in the trap, regardless of the distance from the bead to the coverslip surface. However, the variance of the bead position is the square of the standard deviation of its movements. Thus, a small amount of drift, or noise, or pointing instability in the system can artificially increase the calculated variance of the bead position in the trap, causing the trap stiffness to be underestimated. On the other hand, if unintended low-pass filtering in the QPD occurs, it makes the recorded trajectory smoother than the actual trajectory (Berg-Sorensen et al. 2003), which will reduce the variance of the bead position. Thus, the variance method is prone to systematic errors of unknown sign and size.

The power spectrum method avoids these problems by diagnosing them and circumventing them (Berg-Sorensen and Flyvbjerg 2004). In mathematical terms, the variance is the integral of the power spectrum. The variance, however, is just a single number, and thus it comes with no built-in health checks. The power spectrum, on the other hand, is a whole spectrum that can be checked against theoretical expectations for what it should look like, being the spectrum of Brownian motion. This calibration method relies on the fact that the motion of a trapped bead over long periods of time is controlled by the restoring force of the trap, which acts as a linear spring, and this motion is described by a single characteristic frequency. Motion over short times is random diffusion, which depends on the drag coefficient of the bead but not the trap stiffness. It is described by an infinite number of frequencies. A fit of the bead's power spectrum is used to calculate its fc, at which the transition between trap-dominated motion of the bead (at low frequencies) and diffusion-dominated motion (at high frequencies) occurs. Calculation of the power spectrum is described in detail by Gittes and Schmidt (1998), Svoboda and Block (1994), and Flyvbjerg and colleagues (Berg-Sorensen and Flyvbjerg 2004; Berg-Sorensen et al. 2006; Tolic-Norrelykke et al. 2006). MatLab software computes experimental power spectra for trapped beads and fits theoretical power spectra to them (documented and available in Hansen et al. [2006]). It also performs a number of “health tests” on the data and displays the results graphically.

The corner frequency of the bead (fc) depends on both the trap stiffness and the drag coefficient of the bead. The power spectrum shows noise sources at specific frequencies that are unrelated to bead motion (e.g., 60 Hz), low-frequency noise caused by drift, and high-frequency power loss caused by low-pass filtering, intended or not (Berg-Sorensen et al. 2003; Berg-Sorensen and Flyvbjerg 2004). These distortions of the pure spectrum of Brownian motion are assumed to be negligible when trap stiffness is calculated from the variance in the bead position. However, the power spectrum depends on the bead's drag coefficient, and hence the distance from the bead to the coverslip surface, unless the bead is in bulk solution (Schaffer et al. 2007). Both are easily measured, however, using a piezoelectric xy-stage or calibrated AODs (Tolic-Norrelykke et al. 2006).

Digital Frequency Synthesizers and Creating Multiple Simultaneous Traps

The computer-controlled positioning of the trap by the AODs must be very fast (≥10 KHz) and very accurate (≤1 nm) for effective feedback control of trap position or for modulating the frequency input to the AODs to make multiple traps (Molloy 1998). For nanometer precision positioning of the trap over large ranges of AOD deflections, digital frequency synthesizers are needed to drive the AODs. They produce radio frequency (RF) signals at 30–80 MHz that are amplified to drive the piezoelectric transducer on the AOD. The result is stable and extremely accurate positioning of the trap because the same digital signal is always synthesized for a set digital input. This always results in the same AOD deflection to a level limited by the digital resolution. For a 13-bit digital frequency synthesizer, bit noise results in an error of 0.012% (1/213) in the trap position, corresponding to 1.2 nm over the 10-μm range of movement for the AODs in this design; 24- and 32-bit digital frequency synthesizers reduce this error to levels well below 1 nm. In contrast, analog frequency synthesizers have an error of approximately ±0.25% in converting the 0 to 1-V analog input into an RF signal (comparable to the sensitivity of most analog voltage measuring devices). A 0.25% error in laser deflection by an AOD with a 10-μm range in the sample plane corresponds to a position instability of 25 nm. This is unacceptable for most motor assays. However, if the range of trap movement in the sample plane by deflection of the AODs is decreased, this position instability is decreased as well.

Today's digital frequency synthesizers can update signals with speeds of up to 100 KHz or higher. This is useful for creating multiple traps by quickly rastering the position of the beam or for feedback control of the optical trap. In practice, the scanning rate of the QPD between trap positions must be about an order of magnitude faster than the fc of the bead (~100–1000 Hz) to create multiple traps by rastering the beam back and forth rapidly between two positions (Visscher et al. 1996; Molloy 1998; Visscher and Block 1998). A scanning frequency of 10 kHz, adjusting the position of the trap every 100 μsec, is usually sufficient. Caution must be used in updating signals at high speeds. For example, modulating the 17- to 33-MHz RF signal to drive a tellurium dioxide AOD (IntraAction Corp.) at 10 kHz induces a carrier frequency of 10 kHz on that signal. An AOD driven in this manner deflects the laser as though it were a convolution of diffraction gratings from the megahertz input signal and the 10-kHz modulation (Molloy 1998). The result is three different traps: the original first-order deflected beam, and two beams at a distance from the original beam corresponding to the 10-kHz carrier frequency (~6 nm in this setup). This effect is not critical at 10 kHz because the distance between the three beams is small compared to the size of the bead. At much higher frequencies, however, multiple weak “ghost” traps can be created in the sample plane (Molloy 1998). To determine the range of conditions under which the trap acts as a single linear spring with a linear restoring force, power spectra can be taken at various driving frequencies with trapped beads of several sizes.

Two alternatives exist for creating multiple traps in this system that eliminate concerns about rastering the trap quickly between two positions. First, two separate RF inputs from two digital frequency synthesizers can be mixed before amplification and used to drive a single piezoelectric transducer on the AOD. Two different independently controllable first-order deflections of the incident beam are produced and can be used for dual-beam trapping experiments. Second, the zero-order undeflected beam from the AOD can be used as a fixed trap. Feedback can be performed using the beam deflected in both x and y. The dual-beam trapping experiments described below are compatible with this type of system. However, they still use force feedback on the movable trap to gain high-resolution step-size information.

Force Clamp for Measuring the Velocity and Step Size of a Molecular Motor at Constant Load

Force clamps are commonly used in optical traps to maintain a relatively constant force on the trapped bead by keeping a constant distance between the centers of the bead and the trap. Accurate step-size measurements are produced which are independent of linkage stiffness. This has been a very powerful tool for molecular motor studies, enabling unprecedented accuracy in measuring the velocity and step size of a molecular motor at constant load under various conditions. Force clamping has allowed for studies that determine the effect of load on the ATPase kinetics and stepping velocity of molecular motors much more precisely than did previous experiments (Visscher and Block 1998; Visscher et al. 1999; Rief et al. 2000; Schnitzer et al. 2000; Veigel et al. 2002; for review, see Mehta 2001).

Position clamping has also been used, in which the bead position is maintained as constant as possible to create isometric conditions (Finer et al. 1994; Simmons et al. 1996). This allows for isometric force measurements over short distances (i.e., with nonprocessive motors, which take one power stroke and then diffuse away from the filament). In practice, position clamps create a stiffer trap, not an isometric one. Force measurements on nonprocessive motors are still very difficult to perform, because the trap is not completely isometric (particularly on fast timescales) and because of compliances in the linkages of the system (Mehta and Spudich 1998).

For either force or position clamping, the response time of the computer program must be very fast, updating the trap position on submillisecond timescales. Events on shorter timescales can be resolved, and the constant force or position conditions imposed by the feedback are subject to smaller fluctuations. A compiled low-level software routine on a dedicated digital signal processor is often used to perform feedback calculations for adjusting the trap position in response to the bead position. A force clamp routine must always begin with a calibration of both trap stiffness and the voltage response of the QPD to known distance deflections of the bead. A proportional integral derivative (PID) method is then used to calculate the adjustment of the bead position so that force remains constant as the motor steps along the filament. A tutorial on PID controllers is available from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Michigan (http://www.engin.umich.edu/group/ctm/PID/PID.html), and a good reference is Franklin et al. (1994).

To maximize the working range of the QPD, the feedback system holds the bead in place, imaged on one edge of the QPD. The motor steps against the trap until the distance from the center of the bead to the trap multiplied by the trap stiffness is equal to the desired load. Feedback then maintains the separation between the bead and the trap to keep the force constant. The motor takes steps under constant load until it reaches the other end of the working range of the QPD, ~300 nm away in the setup described here. When the bead begins to leave the linear range of the QPD, the trap stops moving, the force increases as the motor steps, and eventually the motor stalls and returns to the center. Use of the above techniques depends heavily on the properties of the motor to be studied. The next section describes optical trapping experiments on different types of motors, focusing on myosin as a particular example.

OPTICAL TRAPPING EXPERIMENTS

Measurable Parameters by Optical Trapping of Processive and Nonprocessive Motors

Optical trapping experiments have been performed on both processive and nonprocessive motors. Processive motors undergo multiple productive catalytic cycles and associated mechanical steps per diffusional encounter with their filament. Nonprocessive motors bind, undergo at most one productive catalytic cycle associated with a single mechanical step, and then diffuse away from the filament. Different experimental geometries can be used for processive and nonprocessive motors, and different information is gained from them. The dwell time (the average time that the motor spends attached to the filament per step) can accurately be determined with both motors. For processive motors, the transitions between successive steps are used. For nonprocessive motors, the sudden drop in variance of the bead position is observed when the motor binds to the filament, causing a sudden increase in the stiffness of the spring (the bead-motor-filament linkages confining the bead to the trap [Molloy et al. 1995]). In certain cases, dwell times of nonprocessive motors can be measured by using correlated thermal diffusion (Mehta et al. 1997).

To measure processive motor step sizes, the compliances in the system (the linkages between the beads, motors, and filaments, as well as compliances within the motor) must be measured and corrected for in a fixed trap (Svoboda et al. 1993; Svoboda and Block 1994). Techniques for oscillating the bead have been used to measure step sizes independent of system compliances (Mehta et al. 1999c; Veigel et al. 2002). Step sizes are most accurately measured with an optical force clamp (Visscher et al. 1999; Rief et al. 2000; Rock et al. 2001), which gives an error of <1 nm. The broad step-size distributions of some processive motors in an optical force clamp (e.g., myosin VI [Rock et al. 2001]) reflect the range of step sizes taken by these motors. With nonprocessive motors, only a single binding event and corresponding fraction of a single catalytic cycle are observed. Because of Brownian motion, the position of the bead is not well known before the binding event. This produces a large spread of values in the measured step size (Molloy et al. 1995).

Processive motors can walk several steps out of the center of a fixed trap. This causes the separation between the trap and the bead and therefore the load to increase until they stall. Thus, the stall force of these motors can be measured. Unless the trap is extremely stiff, the force by single nonprocessive motors is difficult to measure because of the short distances these motors travel out of the trap. In this case, the optical trap must therefore be nearly isometric. Furthermore, the bead-motor linkage must be very stiff to prevent the motor from simply pulling out its linkage to the bead rather than pulling against the nearly isometric trap. Forces of single nonprocessive myosins span a wide range (1–7 pN) (Finer et al. 1994; Molloy et al. 1995). This suggests large systematic error in the experiment, possibly because of variability in the bead-motor linkage stiffness (Mehta and Spudich 1998).

Assays with processive motors can use a single-bead geometry, in which the motor is attached to a polystyrene bead held in an optical trap, and the filaments are attached to the glass coverslip surface. Although this geometry is very simple, it is also somewhat restrictive. Motors that must turn around their filament to walk are not suited to the single-bead geometry, although a few mechanical advances may take place before the turning becomes a problem. For nonprocessive motors and motors that must twirl around their filament to walk, the dumbbell geometry (Fig. 1, left) is preferable. In this setup, the filament track is trapped between two polystyrene beads that are held in two traps (Finer et al. 1994). Alternatively, one of the two beads can be permanently attached to the surface. This tethered particle assay is useful for processive motors that turn around their filaments, in particular with RNA polymerase (Wang et al. 1998). In a dumbbell experiment, a sparse coating of glass beads on a coverslip acts as a surface platform for the motors. Steps are measured as displacements of the filament dumbbell in the two optical traps. A dual-trap setup is required, but accurate step sizes can be measured using force feedback on only one of the two traps for actin-based motors (Rock et al. 2001). Kerssemakers et al. (2006) have developed a powerful automated procedure to identify the step transitions in the resulting data traces. A procedure for performing these assays on myosins V and VI is described below.

Single-bead Optical Trapping Assays on Processive Motors

In single-bead geometry assays on myosin V, the coverslip is coated with neutravidin, and biotinylated actin filaments are then flowed in and attached to the surface (for details, see Rock et al. 2000). For assays on microtubule-based motors, microtubules adsorb nonspecifically to poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips (Visscher et al. 1999). Alternatively, axonemes (large bundles of 20 microtubules) can be adsorbed nonspecifically to glass for some assays (Thorn et al. 2000).

Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-motor fusions are commonly used to attach motors to polystyrene beads in an oriented fashion. Many recombinantly expressed cytoskeletal motors have been fused with GFP. The GFP is most often placed at the end of the coiled-coil region, where it should not interfere with the motile properties of the motor. GFP has been used to couple a variety of both recombinant kinesins and myosins to beads or to the coverslip surface in an oriented fashion (Thorn et al. 2000; Rock et al. 2001). If single-molecule motility is seen when the GFP is imaged (by an evanescent field or conventional microscopy), the same assay conditions and construct can be used for optical trapping on that motor (Thorn et al. 2000; Rock et al. 2001). A specific linkage to couple a nonenzymatic portion of a motor protein to the bead has not been needed. For example, squid axoplasm kinesin may bind preferentially to carboxylated beads because of a positively charged region in its coiled-coil and has been successfully used in many experiments (see, e.g., Svoboda et al. 1993; Visscher et al. 1999). However, nonspecific adsorption of some motors can cause them to denature or, more dangerously, can inhibit their activity without completely inactivating them. Therefore, a specific linkage of a nonenzymatic portion of the motor to the bead or to the surface is preferred.

The protocol Attachment of Anti-GFP Antibodies to Microspheres for Optical Trapping Experiments (Spudich et al. 2011a) describes the nonspecific attachment of a purified monoclonal anti-GFP antibody to carboxylated 0.3- to 1-μm beads. It is also possible to use a sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester and N-ethyl-N′-(dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) to couple carboxylated beads to primary amine groups on purified polyclonal anti-GFP antibodies (Thorn et al. 2000). GFP-motor fusion proteins can then be adsorbed to the beads through the antibody in the proper orientation for motility. After anti-GFP antibody is attached to the beads, they last ~3 d at 4°C. The beads should not be stored in reducing buffers, because this degrades the antibody. Kinesins and myosins can be adsorbed onto these beads directly, by incubation for 10 min at 4°C (Thorn et al. 2000; Rock et al. 2001).

Bead size is often important in optical trapping assays. Large beads (~1 μm) are easier to trap than smaller beads, and higher trap stiffnesses can be achieved with large beads. Smaller beads (~0.2–0.3 μm) can resolve faster events than large beads because their fc is higher by a factor proportional to their radius. In a 1064-nm optical trap, small beads have decreased stiffness relative to beads that are the same size as the wavelength of the trapping laser (Simmons et al. 1996). However, resolution of steps has not usually been decreased relative to large beads (Visscher et al. 1999; Rief et al. 2000). When submillisecond timescales are measured, small beads (Nishiyama et al. 2001) or a very stiff trap is needed, because the fc of the bead is also proportional to the trap stiffness. The minimum size beads that can be centrifuged in a tabletop centrifuge are 0.5 μm. Because coupling beads to motors often involves centrifugation, smaller beads should be column purified. Protocols are the same for 0.5-μm beads as for 1-μm beads, because a large excess of antibody is used to coat beads. However, a higher concentration of motor relative to the volume of the beads may be needed when motors are attached to small beads, because the solvent-accessible surface area will be larger relative to the volume of the small beads.

Dumbbell Assay for Nonprocessive Motors or Motors that Must Turn around Filaments

Unlike the single-bead trapping geometry, the dumbbell geometry (Fig. 1, left) can be used for both processive and nonprocessive motors, as well as for motors that turn around their filament. It is also useful for motors with a short linkage between their motor domains and the bead attachment, because the trapped beads are held ~1 μm farther from the surface. Thus, it is easier to connect active motors to their filaments without holding the beads too close to the surface. In the dumbbell geometry, the filament is held between two 1-μm polystyrene beads. The coverslip surface is coated with 1.5-μm glass beads, which serve as platforms for motors. Therefore, the trapped beads are ~1 μm away from the coverslip surface. The filament slides and the motor pulls against the trapped bead at one end of the filament while pushing the filament toward the other trapped bead. In myosin-based assays, the dumbbell is created from biotinylated actin filaments coupled to neutravidin-coated polystyrene beads (Rock et al. 2000). Similarly, a biotinylated microtubule was coupled to streptavidin beads for optical trapping assays on the nonprocessive kinesin family member, nonclaret disjunctional (NCD) (deCastro et al. 2000). The assay described in The Optical Trapping Dumbbell Assay for Nonprocessive Motors or Motors That Turn around Filaments (Spudich et al. 2011b) was performed on recombinant fusions of GFP with both myosin V and myosin VI (Rock et al. 2001).

Use of Force Clamps

Force clamping is extremely useful for studying the movement characteristics of molecular motors. Figure 5 shows stepping traces using feedback on the trap in the single-bead geometry with myosin V (Rief et al. 2000). Similar results are obtained using the dumbbell geometry (Fig. 1, left). If the filament track for the motor is relatively flexible (like actin), feedback can be performed on just one of the two beads to make accurate step-size measurements. For microtubule-based assays, in which the filament is very stiff, it is necessary to program feedback on both of the beads. To perform force-clamp measurements using two traps, the stiffness of both traps must be known. As the motor pulls one bead and pushes the other, constant force on both beads and a constant distance between them can then be maintained. In actin-based assays, in which the filament is quite flexible, the tension borne by the motor caused by the bead being pushed is negligible over short distances. While stepping, the myosin will pull itself along the actin toward one of the two beads (e.g., the left-hand bead in Fig. 1, left) and push the actin out toward the other (e.g., the right-hand bead in Fig. 1, left). The bead that the myosin is pulling against is used for force feedback. If the actin filament is held with a slight amount of slack, the right-hand bead does not move throughout the entire feedback range of the left-hand bead (~300 nm, in the setup described here) and thus has no effect on the other components of the system. Force-feedback stepping measurements can then be conducted using only the left-hand bead.

FIGURE 5.

Myosin V stepping using a force clamp. (Red trace) Unfiltered data of the position of a trapped polystyrene bead (Rief et al. 2000); (black trace) position of the trap following the bead to maintain constant load. Data were taken at 3 μm ATP.

Assuring that Observations Are of Single Molecules

Being able to recognize single-molecule motility is very important when the force, step size, and processivity of motors are being assessed in an optical trap. Multiple motors creating the movement can lead to misinterpretation of the data and erroneous conclusions regarding all of these parameters. In the assays described in this article, it can be difficult to determine the motor concentration that gives single-molecule movement, because the number of motors per bead depends on several factors, including antibody quality and the quantity of antibody that adsorbs to the beads.

To determine whether a new motor is processive, one should begin at a high motor concentration and successively decrease to the single-molecule level. Whenever possible, motor motility should be characterized in both conventional and evanescent field microscope assays. The former can give evidence of whether a motor is processive or nonprocessive, whereas the latter provide the most direct and stringent measure of processivity. These assays are summarized by Rock et al. (2000). Briefly, conventional microscope assays characterize motor motion at high concentration and gradually decrease in concentration to the single-molecule level. The number of molecules needed to sustain movement of filaments can be found with Poisson statistics (Block et al. 1990). The GFP linkage to anti-GFP antibodies is useful in studies of motor processivity. It can be used in conventional microscope-based assays to determine motor densities that should give single-molecule motility. These conditions can then be duplicated in an optical trap. GFP can also be used under similar conditions without antibodies to image processive motor movements directly in an evanescent field microscope (Rock et al. 2001). However, there are better fluorescent probes for this purpose (e.g., Cy3 and Cy5).

CONCLUSIONS

Optical trapping experiments directly measure the velocity, force, step size, and processive run length of molecular motors. Force-feedback techniques have allowed extremely high-resolution determination of the step sizes of molecular motors, as well as studies of the effect of load on their ATPase kinetics and stepping velocity. The optical layout of the trap has been greatly simplified and new capabilities have been added by the ability to control the stiffness of the trap, positioning, making multiple traps, force feedback, and position feedback using AODs. Optical traps have been used to measure properties of molecular motors directly for more than a decade, and it is difficult to imagine what the state of knowledge would be without these assays. The ever-increasing range of capabilities of optical traps continues to make this technique one of the most powerful for elucidating the mechanisms of molecular motors and other biological systems in which force and movement are critical properties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Henrik Flyvbjerg for invaluable discussions and help with the section on calibration considerations. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM33289) to J.A.S.

REFERENCES

- Ashkin A. Forces of a single-beam gradient laser trap on a dielectric sphere in the ray optics regime. Methods Cell Biol. 1998;55:1–27. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Sorensen K, Flyvbjerg H. Power spectrum analysis for optical tweezers. Rev Sci Instrum. 2004;75:594–612. [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Sorensen K, Oddershede L, Florin E-L, Flyvbjerg H. Unintended filtering in a typical photodiode detection system for optical tweezers. J Appl Phys. 2003;93:3167–3176. [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Sorensen K, Peterman EJG, Weber T, Schmidt CF, Flyvbjerg H. Power spectrum analysis for optical tweezers. II. Laser-wavelength dependence of parasitic filtering and how to achieve high bandwidth. Rev Sci Instrum. 2006;77:063106–1–063106-11. [Google Scholar]

- Berns MW, Aist JR, Wright WH, Liang H. Optical trapping in animal and fungal cells using a tunable, near-infrared titanium-sapphire laser. Exp Cell Res. 1992;198:375–378. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90395-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block SM, Goldstein LS, Schnapp BJ. Bead movement by single kinesin molecules studied with optical tweezers. Nature. 1990;348:348–352. doi: 10.1038/348348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant Z, Altman D, Spudich JA. The power stroke of myosin VI and the basis of reverse directionality. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:772–777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610144104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCastro MJ, Fondecave RM, Clarke LA, Schmidt CF, Stewart RJ. Working strokes by single molecules of the kinesin-related microtubule motor ncd. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:724–729. doi: 10.1038/35036357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer JT, Simmons RM, Spudich JA. Single myosin molecule mechanics: Piconewton forces and nanometre steps. Nature. 1994;368:113–119. doi: 10.1038/368113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin GF, Powell JD, Emami-Naeini A. Feedback control of dynamic systems. 3rd ed. Addison-Wesley; Reading, Massachusetts: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles J, Schnapp BJ, Sheetz MP. Tracking kinesin-driven movements with nanometre-scale precision. Nature. 1988;331:450–453. doi: 10.1038/331450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittes F, Schmidt CF. Signals and noise in micromechanical measurements. Methods Cell Biol. 1998;55:129–156. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60406-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen PM, Tolic-Norrelykke IM, Flyvbjerg H, Berg-Sorensen K. Faster version of Matlab package for precise calibration of optical tweezers. Comput Phys Commun. 2006;175:572–573. [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Hudspeth AJ, Vale RD. Movement of microtubules by single kinesin molecules. Nature. 1989;342:154–158. doi: 10.1038/342154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerssemakers JW, Munteanu EL, Laan L, Noetzel TL, Janson ME, Dogterom M. Assembly dynamics of microtubules at molecular resolution. Nature. 2006;442:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature04928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kron SJ, Spudich JA. Fluorescent actin filaments move on myosin fixed to a glass surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83:6272–6276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A. Myosin learns to walk. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1981–1998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.11.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AD, Spudich JA. Single myosin molecule mechanics. Adv Struct Biol. 1998;5:229–270. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AD, Finer JT, Spudich JA. Detection of single-molecule interactions using correlated thermal diffusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:7927–7931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AD, Finer JT, Spudich JA. Reflections of a lucid dreamer: Optical trap design considerations. Methods Cell Biol. 1998a;55:47–69. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AD, Finer JT, Spudich JA. Use of optical traps in single-molecule study of nonprocessive biological motors. Methods Enzymol. 1998b;298:436–459. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)98039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AD, Rief M, Spudich JA. Biomechanics, one molecule at a time. J Biol Chem. 1999a;274:14517–14520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AD, Rief M, Spudich JA, Smith DA, Simmons RM. Single-molecule biomechanics with optical methods. Science. 1999b;283:1689–1695. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta AD, Rock RS, Rief M, Spudich JA, Mooseker MS, Cheney RE. Myosin-V is a processive actin-based motor. Nature. 1999c;400:590–593. doi: 10.1038/23072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ménétrey J, Bahloul A, Wells AL, Yengo CM, Morris CA, Sweeney HL, Houdusse A. The structure of the myosin VI motor reveals the mechanism of directionality reversal. Nature. 2005;435:779–785. doi: 10.1038/nature03592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy JE. Optical chopsticks: Digital synthesis of multiple optical traps. Methods Cell Biol. 1998;55:205–216. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy JE, Burns JE, Kendrick-Jones J, Tregear RT, White DCS. Movement and force produced by a single myosin head. Nature. 1995;378:209–212. doi: 10.1038/378209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman KC, Block SM. Optical trapping. Rev Sci Instrum. 2004;75:2787–2809. doi: 10.1063/1.1785844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman KC, Chadd EH, Liou GF, Bergman K, Block SM. Characterization of photodamage to Escherichia coli in optical traps. Biophys J. 1999;77:2856–2863. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman KC, Abbondanzieri EA, Block SM. Measurement of the effective focal shift in an optical trap. Opt Lett. 2005;30:1318–1320. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.001318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M, Muto E, Inoue Y, Yanagida T, Higuchi H. Substeps within the 8-nm step of the ATPase cycle of single kinesin molecules. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:425–428. doi: 10.1038/35070116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice SE, Purcell TJ, Spudich JA. Building and using optical traps to study properties of molecular motors. Methods Enzymol. 2003;361:112–133. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)61008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rief M, Rock RS, Mehta AD, Mooseker MS, Cheney RE, Spudich JA. Myosin-V stepping kinetics: A molecular model for processivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:9482–9486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock RS, Rief M, Mehta AD, Spudich JA. In vitro assays of processive myosin motors. Methods. 2000;22:373–381. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock RS, Rice SE, Wells AL, Purcell TJ, Spudich JA, Sweeney HL. Myosin VI is a processive motor with a large step size. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:13655–13659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191512398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer E, Norrelykke SF, Howard J. Surface forces and drag coefficients of microspheres near a plane surface measured with optical tweezers. Langmuir. 2007;23:3654–3665. doi: 10.1021/la0622368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer MJ, Visscher K, Block SM. Force production by single kinesin motors. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:718–723. doi: 10.1038/35036345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheetz M. Laser tweezers in cell biology. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheetz MP, Spudich JA. Movement of myosin-coated fluorescent beads on actin cables in vitro. Nature. 1983;303:31–35. doi: 10.1038/303031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RM, Finer JT, Chu S, Spudich JA. Quantitative measurements of force and displacement using an optical trap. Biophys J. 1996;70:1813–1822. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79746-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Cui Y, Bustamante C. Overstretching B-DNA: The elastic response of individual double-stranded and single-stranded DNA molecules. Science. 1996;271:795–799. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich JA, Kron SJ, Sheetz MP. Movement of myosin-coated beads on oriented filaments reconstituted from purified actin. Nature. 1985;315:584–586. doi: 10.1038/315584a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich JA, Rice SE, Rock RS, Purcell TJ, Warrick HM. Attachment of anti-GFP antibodies to microspheres for optical trapping experiments. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011a doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot066670. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot066670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spudich JA, Rice SE, Rock RS, Purcell TJ, Warrick HM. The optical trapping dumbbell assay for nonprocessive motors or motors that turn around filaments. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011b doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot066688. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot066688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen W, Smith D, Simmons R, Sleep J. Mapping the actin filament with myosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:14949–14954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261560698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba RE, Sheetz MP. Basic laser tweezers. Methods Cell Biol. 1998;55:29–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda K, Block SM. Biological applications of optical forces. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1994;23:247–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda K, Schmidt CF, Schnapp BJ, Block SM. Direct observation of kinesin stepping by optical trapping interferometry. Nature. 1993;365:721–727. doi: 10.1038/365721a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn KS, Ubersax JA, Vale RD. Engineering the processive run length of the kinesin motor. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1093–1100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolic-Norrelykke SF, Schaffer E, Howard J, Pavone FS, Julicher F, Flyvbjerg H. Calibration of optical tweezers with positional detection in the back-focal-plane. Rev Sci Instrum. 2006;77:103101–103111. [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima YY, Kron SJ, Mcnally EM, Niebling KR, Toyoshima C, Spudich JA. Myosin subfragment-1 is sufficient to move actin filaments in vitro. Nature. 1987;328:536–539. doi: 10.1038/328536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda TQ, Warrick HM, Kron SJ, Spudich JA. Quantized velocities at low myosin densities in an in vitro motility assay. Nature. 1991;352:307–311. doi: 10.1038/352307a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale RD, Reese TS, Sheetz MP. Identification of a novel force-generating protein, kinesin, involved in microtubule-based motility. Cell. 1985;42:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veigel C, Wang F, Bartoo ML, Sellers JR, Molloy JE. The gated gait of the processive molecular motor, myosin V. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:59–65. doi: 10.1038/ncb732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher K, Block SM. Versatile optical traps with feedback control. Methods Enzymol. 1998;298:460–489. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)98040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visscher K, Gross SP, Block SM. Construction of multiple-beam optical traps with nanometer-level resolution position sensing. IEEE J Select Top Quantum Elect. 1996;2:1066–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Visscher K, Schnitzer MJ, Block SM. Single kinesin molecules studied with a molecular force clamp. Nature. 1999;400:184–189. doi: 10.1038/22146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MD, Schnitzer MJ, Yin H, Landick R, Gelles J, Block SM. Force and velocity measured for single molecules of RNA polymerase. Science. 1998;282:902–907. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida T, Iwane AH. A large step for myosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:9357–9359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]