Abstract

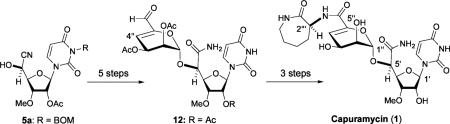

A concise total synthesis of capuramycin (1), a promising preclinical TB drug lead, is achieved by high-yield formations of the cyanohydrin 5a and 4″,5″-glycal derivative 12. Capuramycin can be synthesized in eight steps from the uridine building block 5a with >30% overall yield. The synthetic intermediates reported here are useful for generation of analogs to improve pharmacokinetic properties of capuramycin.

Graphical Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) causes tuberculosis (TB) and is responsible for nearly two million deaths annually.1 In particular, people who are HIV-AIDS patients are susceptible to TB infection. There are significant problems associated with treatment of AIDS and Mtb coinfected patients. Rifampicin and isoniazid (a key component of the DOTS therapy2) induce the cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme, one of the enzymes responsible for drug metabolism, in liver which shows significant interactions with protease inhibitors for HIV infections.3 In addition, rifampicin strongly interacts with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors for HIV. Thus, clinicians avoid starting highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which consists of three or more highly potent reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors, until the TB infection has been cleared.4 Moreover, the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains of Mtb seriously threatens TB control and prevention efforts. Thus, there is an urgent need and significant interest in developing new TB drugs.5

Since peptidoglycan (PG) is an essential bacterial cell-wall polymer, the machinery for PG biosynthesis provides a unique and selective target for antibiotic action.6 However, only a few enzymes in PG biosynthesis such as the penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), which are inhibited by the β-lactams and glycopeptides, are extensively studied. Thus, the enzymes associated with the PG biosynthesis (i.e., MurA, B, C, D, E, and F, MraY, and MurG) are still considered to be a source of unexploited drug targets.7 Our interest in targets related to PG biosynthesis is MraY, which catalyzes the transformation of UDP-N-acylmuramyl-l-alanyl-γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelyl-d-alanyl-d-alanine (Park's nucleotide) to prenylpyrophosphoryl-N-acylmuramyl-l-Ala-γ-d-glu-meso-DAP-d-Ala-d-Ala (lipid I). MraY is inhibited by nucleoside-based complex natural products such as muraymycin, liposidomycin, caprazamycin, and capuramycin.8 Capuramycin (1) and its analogs exhibited significant mycobacterial growth inhibitory activities in vitro and in vivo (Scheme 1) and very low toxicity in mice.9 Moreover, a capuramycin analog killed M. tuberculosis much faster than other first-line TB drugs (>90% of the bacilli were killed within 48 h) and thus could dramatically reduce the time frame for effective anti-TB chemotherapy.10 Therefore, capuramycin and its congeners have been considered important lead molecules for the development of a new drug for MDR-TB infections. However, extensive SAR studies of capuramycins to improve pharmacokinetic properties have been limited due to difficult modifications of the desired position(s) of the complex natural product with biologically interesting functional groups. Consequently, it is essential to establish a concise and convergent synthesis of capuramycin that is amenable to synthesis of analogs for SAR studies. To date, Knapp and Nadan have reported the only total synthesis of capuramycin.11 Their synthesis requires 22 linear steps from diisopropylidene-d-glucofuranose, and relatively lengthy synthesis of the manno-pyranuroate glycosyl donor. We now report a concise total synthesis of capuramycin that is amenable to performing comprehensive medicinal chemistry studies based on the core structure of capuramycin.

Scheme 1.

Preliminary Studies on Glycosylation of 5a and the Revised Synthetic Strategy for Capuramycin (1)

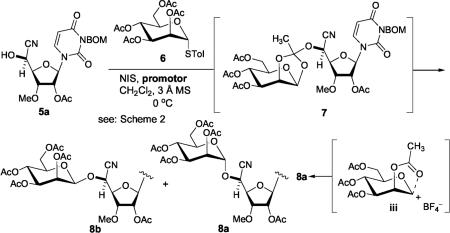

In our preliminary synthetic studies of the advanced intermediate ii (Scheme 1), glycosylation of the cyanohydrin 5a with β-d-manno-pyranuronate imidate i provided the desired α-linked mannuronic acid derivative with very low yield (5–15%) even after extensive optimization efforts. Moreover, E2 elimination to form the 4″-enopyranosiduronic acid derivative ii did not give satisfactory results (35–45% with DBU).12 Based on the preliminary studies summarized in Scheme 1, we revised the synthetic route for capuramycin (1) in which we envisioned performing glycosylation of the cyanohydrin 5a with the tetraacetyl thio-α-D-mannopyranoside 6, followed by one-pot oxidation of the C-6″ alcohol and elimination of the acetate at the C-4″ position to form the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 12. The revised synthetic route for capuramycin illustrated in Scheme 1 would allow for the synthesis of the intact molecule from readily accessible building blocks with a minimum number of protecting group manipulations.

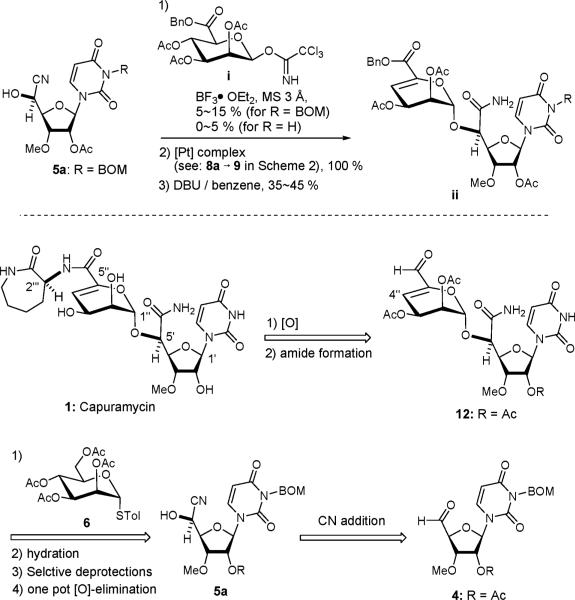

Scheme 2 illustrates our synthetic route for capuramycin (1). The partially protected uridine 213 was converted to the 2-O-acetyl-3-O-methyl-uridine derivative 3 through monomethylation using nBu2SnO, acetylation, and detritylation reactions. The primary alcohol of 3 was oxidized under Pfitzner-Moffatt conditions (DCC, Cl2CHCO2H, DMSO)14 to provide the corresponding aldehyde 4, which was utilized after passing through a SiO2 plug. The aldehyde 4 was unstable against Brønsted and Lewis bases (i.e., Et3N, DABCO, cinchona alkaloids, triphenylphosphine, and triphenylphosphine oxide). Because of the instability of 4 when exposed to bases, we explored cyano addition reactions of carbonyl molecules promoted by Lewis acids15 or under neutral conditions. Several Lewis acid promoted trimethylsilylcyanations of 4 were examined. In all cases, cyanohydrin synthesis furnished a mixture of 5a and 5b in favor of undesired 5b with moderate yields.16 For example, the cyanosilyation of 4 with ZnI2 (100 mol %) gave rise to a mixture of the cyanohydrins in 60% yield with a 5a/5b ratio of ~1:2 after desilylation. The same reaction with the (S)-or (R)-BINOL-Ti(OiPr)4 complex resulted in a 5a/5b selectivity of ~1:1.5 regardless of the configuration of BINOL. On the contrary, the addition of TMSCN to 4 with 10 mol% of Ti(OiPr)4 in CH2Cl2–H2O (1%) provided a mixture of 5a and 5b with the 5a/5b ratio of 2:1 in 90% yield from 3. Because addition of H2O accelerated the cyanosilylation reaction of 4, we speculated that a Ti-oxo species is responsible for this transformation.17 Although the cyanosilylation reaction catalyzed by Ti(OiPr)4 in CH2Cl2–H2O exhibited moderate 5a/5b selectivity, a ten-gram quantity of 5a could easily be synthesized in 60% yield via the convenient achiral Ti reagent.18 In addition, the undesired cyanohydrin 5b could be converted to the desired 5a via a modified Mitsunobu reaction (DIAD, TPP, ClCH2CO2H, pyridine (1:1:1:1))19 and subsequent deacylation with thiourea20 in 90% overall yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthsis of Capuramycin (1)

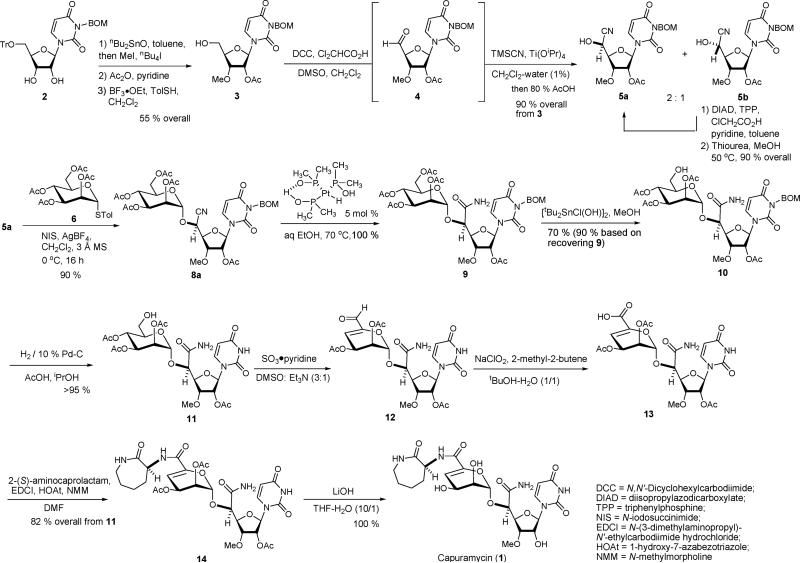

α-Selective mannosylation of 5a with the disarmed glycosyl donor 6 required to investigate an appropriate promoter. The standard NIS/TfOH21-promoted mannosylation of 5a with 6 furnished the orthoester 722 (20%) together with a 2:1 mixture of 8a and 8b (30%) (Table 1). Under the NIS/TfOH conditions the orthoester 7 was not completely rearranged to the O-glycosides even after 16 h at 0 °C. The α/β-selectivity and isolated yield of the desired 8a were not dramatically improved by replacing with other counterion sources (entries 1–3 in Table 1).23 On the contrary, the NIS/AgBF4 promoted mannosylation of 5a provided the orthoester 7 in quantitative yield within 15 min, which underwent the rearrangement within 16 h to afford 8a exclusively (90% isolated yield, entry 4 in Table 1). A shorter reaction time resulted in a mixture of 7 and 8a (entry 5).24 The strong acid salts (i.e., nBu4NClO4, nBu4NOTf, LiClO4, and nBu4NBF4), known to promote glycosylations with thioglycoside and NXS (X = I or Br),25 and the other silver salts26 (i.e., AgClO4 and AgSbF6) were not effective in mannosylation of 5a with 6 (entries 6 and 7 in Table 1). Mechanistically, tetrafluoroborate (BF4−) appears to be an innocent anion, and the intermediate iii may be stabilized by the formation of an intimate ion pair with BF4−.27 Fluoroboric acid (HBF4) generated in situ in the glycosylations using NIS/AgBF4 facilitates the rearrangement of 7 to 8a through iii.28

Table 1.

α-Selective Mannosylation of the Cyanohydrin 5a with 6

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | promotor | time (h) | yield (%)a | 8a/8b |

| 1 | TfOH | 16 | 30 | 2/1 |

| 2 | TMSOTf | 16 | 35 | 2/1 |

| 3 | AgOTf | 16 | 40 | 2.5/1 |

| 4 | AgBF4 | 16 | 90 | 1/0 |

| 5 | AgBF4 | 8 | 55 | 1/0 |

| 6 | Bu4NBF4 | 16 | <5 | – |

| 7 | AgClO4 | 16 | <5 | – |

Combined yield of 8a and 8b.

We have demonstrated the synthesis of a gram quantity of the α-mannosylated cyanohydrin 8a (Scheme 2). The cyano group of 8a was efficiently hydrated using 5 mol % of the Parkins’ [Pt] complex,29 furnishing the corresponding primary amide 9 in quantitative yield. Although the BOM group of the uridine moiety could be deprotected in the late stage of capuramycin synthesis using FeCl3 in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C,30 the best overall yield from 8a to 1 was achieved when the BOM group was removed prior to the oxidation of the primary alcohol (11→12). Selective deacetylation of the primary acetate of 9 was accomplished by using [tBu2SnCl(OH)]2.31 Treatment of the pentaacetate 9 with 1 mol % of the [Sn] reagent in MeOH furnished the C6”-free alcohol 10 in 70% yield (90% yield based on recovering 9). Hydrogenolytic removal of the BOM group of 10 gave 11 in an almost quantitative yield. A mild oxidation-elimination reaction of 11 using modified Parikh-Doering conditions (SO3•pyridine in a biphasic solvent system (DMSO/Et3N = 3/1)32 provided the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde 12 in quantitative yield (determined by 1H NMR analysis). After all volatiles were removed, the aldehyde 12 was oxidized to the corresponding carboxylic acid 13 by using NaClO2. The resulting crude mixture was coupled with (2S)-aminocaprolactam using a standard peptide-forming reaction condition (HOAt, EDCI, and NMM) to yield 14 in 82% overall yield from 11. Saponification of 14 by using LiOH in aq THF provided capuramycin (1) in quantitative yield. The synthetic material was characterized by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and MS.9a,33 In addition, the biological activities of capuramycin synthesized here were evaluated in vitro (IC50) against Mtb MraY and in mycobacterial growth inhibitory assays (MIC).33 These in vitro assay data showed good agreement with those reported in the literature.9

In conclusion, we have developed a concise synthesis of capuramycin (1) in which the versatile aldehyde 12 for the preparation of capuramycin analogs was synthesized in seven steps from 3. Each step summarized in Scheme 2 is operationally very simple and a high-yielding conversion. Moreover, the building blocks 3 and 6 can readily be synthesized in four steps from the commercially available uridine derivative and 2 steps from D-mannose. We will synthesize capuramycin analogs by (1) modifying the structure of 3, (2) reductive amination of 12 with a variety of primary amines, and (3) coupling of 13 with pharmacologically interesting primary and secondary amines. A detailed structure antibacterial activity relationship studies of new capuramycin analogs will be reported elsewhere.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Colorado State University for generous financial support.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and copies of NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Rouhi AM. Chem. Eng. News. 1999;77:52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DOTS (directly observed therapy shortcourse therapy) uses a battery of drugs in a prescribed order to eradicate tuberculosis and avoid the creation of drug-resistant strains of the disease.

- 3.a Cole ST, Alzari PM. Science. 2005;14:214. doi: 10.1126/science.1108379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Stover CK, Warrener P, van Devater DR, Sherman DR, Arain TM, Langhorne MH, Anderson SW, Towell JA, Yuan Y, McMurray DN, Kreiswirth BN, Barry CE, Baker WR. Nature (London) 2000;405:962. doi: 10.1038/35016103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godfrey-Faussett P. AIDS. 2003;17:1079. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000060354.78202.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen J. Science. 2004;306:1872. doi: 10.1126/science.306.5703.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Higashi Y, Strominger JL, Sweeley CC. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b van Heijenoort J. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1998;54:300. doi: 10.1007/s000180050155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c van Heijenoort J. Glycobiology. 2001;11:25R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.3.25r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kimura K, Bugg TDH. Nat. Prod. Pep. 2003;20:252. doi: 10.1039/b202149h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Taha MO, Atallah N, Al-Bakri AG, Pradis-Bleau C, Zalloum H, Yonis KS, Levesque PC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:1218. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lovering AL, de Castro LH, Lim D, Strynadka NJ. Science. 2007;315:1402. doi: 10.1126/science.1136611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wright GD. Science. 2007;315:1373. doi: 10.1126/science.1140374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Singh SB, Barrett JF. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;71:1006. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Antane S, Caufield CE, Hu W, Keeney D, Labthavikul P, Morris K, Naughton SM, Petersen PJ, Rasmussenm BA, Singh G, Yang Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;16:176. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Helm JS, Hu Y, Chen L, Gross B, Walker S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11168. doi: 10.1021/ja036494s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Cudic P, Behenna DC, Yu MK, Kruger RG, Szwczuk LM, McCafferty DG. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:3107. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00653-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Ha S, Chang E, Lo M-C, Park P, Ge M, Walker S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:8415. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Timothy DH, Lloyd AJ, Roper DI. Infect. Disor.: Drug Targets. 2006;6:85. doi: 10.2174/187152606784112128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dini C. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005;5:1221. doi: 10.2174/156802605774463042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Uridat E, Zhang J, Aszodi J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:1209. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Dini C, Drochon N, Feteanu S, Guillot JC, Peixoto C, Aszodi J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:529. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Koga T, Fukuoka T, Harasaki T, Inoue H, Hotoda H, Kakuta M, Muramatsu Y, Yamamura N, Hoshi M, Hirota T. J. Antimicro. Chemother. 2004;54:755. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yamaguchi H, Sato S, Yoshida S, Takeda K, Itoh M, Seto H, Otake N. J. Antibiot. 1986;39:1047. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.39.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy VM, Einck L, Nacy CA. Antimicro. Agents Chemther. 2008;52:719. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01469-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knapp S, Nandan SR. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:281. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uncharacterizable byproducts were isolated in addition to the over-deacetylation products.

- 13.Ito T, Ueda S, Takaku HJ. Org. Chem. 1986;51:931. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a Ranganathan RS, Jones GH, Moffatt JG. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:290. doi: 10.1021/jo00917a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pfitzner KE, Moffatt JG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:3027. [Google Scholar]

- 15.North M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:147., and references therein. Krueger CA, Kuntz KW, Dzierba CD, Wirschun WG, Gleason JD, Snapper ML, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:4284. Mori M, Imma H, Nakai T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:6229..

- 16.The stereochemistry of 5a was established by the advanced Mosher method, see Supporting Information.

- 17.Ti(OiPr)4 is known to form Ti-oxo species such as [Ti7O4](OR)20, [Ti8O6](OR)20, and [Ti12O16](OR)16 with trace amount of water through Ti(OiPr)3(OH), see: Hubert-Pfalzgraf LG. J. Mater. Chem. 2004;14:3113.. Jones AC, Leedham TJ, Wright PJ, Crosbie MJ, Fleeting KA, Otway DJ, O'Brien P, Pemble ME. J. Mater. Chem. 1998;8:1773.. Kurosu M, Lorca M. Synlett. 2005;7:1109..

- 18.We are currently investigating a chiral reagent which promotes the reaction of 4 to 5a with high yield and high selectivity.

- 19.Addition of pyridine was indispensable for successful inversion of the C5′-stereocenter of 5b with ClCH2CO2H.

- 20.Lázár L, Bajza I, Jakab Z, Lipták A. Synlett. 2005;14:2242. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeeneman GH, van Leeuwen SH, van Boom JH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:1331. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The orthoester 7 shows a characteristic chemical shift of 1.78 ppm (CH3) in the 1H NMR spectrum.

- 23.Due to the fact that all triflate ion associated glycosylations with 6 (entries 1-3) yielded a mixture of α- and β-mannosides, the mannosyl carbenium ion generated directly from 6 or through the orthoester 7 would be transformed to the α-glycosyl triflate which furnishes the undesired β-mannoside 8b.

- 24.The formation of orthoesters had previously been reported with a number of different glycosyl donors which react through an oxonium ion intermediate and contain a C2-acetyl group, see: Harreus AH, Kunz H. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1986:717..

- 25.Fukase K, Hasuoka A, Kinoshita I, Aoki Y, Kusumoto S. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:4923. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaeothip S, Pornsuriyasak P, Demchenko AV. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:1542. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.12.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winstein S, Clippinger E, Fainberg AH, Heck R, G. C., Robinson GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956;78:328. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The isolated orthoester 7 could be rearranged to 8a by the treatment with HBF4·OEt2 compex in CH2Cl2.

- 29.Ghaffar T, Parkins AW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:8657. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deprotection of the BOM-protected 13 under these conditions was ~ 40% yield.

- 31.Orita A, Hamada Y, Nakano T, Toyoshima S, Otera J. Chem.-Eur. J. 2001;7:3321. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010803)7:15<3321::aid-chem3321>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parikh JR, Doering WE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:5505. [Google Scholar]

- 33.See Supporting Informataion.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.