Abstract

We determined allelic polymorphisms in the mec complexes of 524 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates by partial or complete sequencing of three mec genes, mecA, mecI, and mecR1. The isolates had been collected over a 10-year period from patients living in rural Wisconsin, where the use of antibiotics was expected to be lower than in the bigger cities. Of the 18 mutation types identified, 16 had not been described previously. The five most common mutations were a mutation 7 nucleotides (nt) upstream from the start site (G→T) in the mecA promoter (34.7%), an E246G change encoded by mecA (2.2%), a cytosine insertion at codon 257 in mecA (13.2%), an N121K change encoded by mecI (7.8%), and a major mecI-mecR1 deletion designated as a class B1 mec complex deletion type (25.4%). There was a high degree of conservation of the amino acid sequence of MecR1. Strains with the same mutations had variable resistance to oxacillin, and the median MIC for isolates that harbored the 7-nt-upstream mutation was lower than that for strains harboring other mutations. Our data suggest that the mecA promoter mutation plays a more important role in determining methicillin resistance than mutations in mecI and mecA do. Eighty-five percent of the tested isolates (n = 148) with the mecA promoter mutation and the class B1 mec complex deletion belonged to the same major clonal group, identified as MCG-2, and harbored the type IV staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec DNA. There was also a wide range of oxacillin MICs for strains with wild-type mecA, mecI, and mecR1 sequences, suggesting that the genetic backgrounds of clinical strains are significant in determining susceptibility to methicillin.

An understanding of the mechanism causing the variation in susceptibility to oxacillin (a surrogate compound for methicillin) in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus is still far from complete. One reason for this is that clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) are often clonal but not always isogenic. Methicillin resistance in S. aureus is gained as a consequence of acquiring the mecA gene, which is located on a 21- to 67-kb-long mobile element called the staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec). The mecA gene, together with two regulatory genes, mecI and mecR1, constitutes a ∼4.2-kb mec complex on the SCCmec. The mec complex is considered to be the key element for determining methicillin resistance in S. aureus. Although mecR1 (a signal transducer gene) and mecI (the repressor gene) largely control the expression of mecA, additional genes may regulate the expression of mecA (1, 2, 12). MRSA strains carrying the mecA gene that codes for an altered form of penicillin-binding protein (PBP), called PBP 2a, have a reduced affinity for beta-lactam antibiotics, including methicillin. Consequently, MRSA strains that produce PBP 2a continue to thrive in the presence of beta-lactam antibiotics (3).

More than 90% of clinical MRSA isolates carry mecA on their chromosomes (4). Any mutation in the mec complex that may affect the function of these genes is expected to affect methicillin resistance as well. A number of mutations in mecI and mecA from clinical isolates have been described previously. Partial deletions of mecR1 and mecI have also been described. However, there are few data available to make any correlation between the different mutations in the mec complex from large collections of clinical MRSA isolates and the corresponding oxacillin MICs. It has been shown by Rosato et al. that different clinical MRSA strains containing the same C→T mutation at nucleotide (nt) position 202 in mecI produce variable amounts of mecA transcripts, suggesting variable repressor activity in those strains (15). Recently, Katayama et al. (7) showed that multiple mutations in mecA produce high-level resistance against beta-lactams.

In the present report, we describe several new mutations present in the mec complexes of 524 clinical MRSA strains collected over a 10-year period (1989 to 1999) from patients living in rural Wisconsin. We compared the oxacillin MICs for strains with single or multiple mutations and determined if individual mutations arose as random, independent events or were present in strains that were clonally related.

(This work was presented in part at the 2002 International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases, Atlanta, Ga.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MRSA strains.

The MRSA clinical strains (n = 524) were collected from 77 health care facilities that included clinics (64%) and hospitals and nursing homes (36%) located in northern and central Wisconsin. The isolates were collected from 1989 to 1999. The frequency distribution of isolates by study year was as follows: 1989, 1; 1990, 5; 1991, 10; 1992, 44; 1993, 89; 1994, 44; 1995, 62; 1996, 53; 1997, 49; 1998, 95; and 1999, 72. The S. aureus strains were identified by colony morphology, Gram staining, and positive tests for catalase and coagulase. Isolates were considered methicillin resistant if the oxacillin MIC was ≥4 μg/ml by the Etest method according to NCCLS standards (13).

mec complex PCR and sequencing.

The list of PCR primers used to amplify mecA, mecI, and mecR1, the expected amplicon sizes, and the locations of the genes on the S. aureus chromosome N315 are shown in Table 1. The sequencing primers used were the same as the PCR primers. The nucleotide positions for PCR primers are based on the sequence submitted to GenBank under accession number AP003129. The mec complex segments were amplified by the colony PCR method described below. Each amplicon was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Valencia, Calif.) and then sequenced in either an ABI 377 DNA sequencer or an ABI 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

TABLE 1.

PCR and sequencing primers, locations on chromosomes, and expected amplicon sizes for mec genesa

| mec complex primers | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Nucleotide positions | Annealing temp (°C) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mecAF1 | AGATGATAACACCTTCTACAC | 46278-47148 | 48 | 870 |

| mecAR1 | CTAATAGATGTGAAGTCGC | |||

| mecAF2 | AAATTTCATCTTACAACTAATG | 45547-46350 | 48 | 803 |

| mecAR2 | TGGATAATCACTTGGTATATC | |||

| mecAF3 | TGAAGATATACCAAGTGATTATC | 44899-45571 | 48 | 672 |

| mecAR3 | CTCGTTACAGTGTCACTTTC | |||

| mecR1F1 | ACCAAACCCGACAACTAC | 46981-47765 | 53.5 | 784 |

| mecR1R1 | TTCACATGTGATAGTTCATGTAG | |||

| mecR1F2 | CGAAACCATGAATGACAA | 47706-48571 | 53.5 | 865 |

| mecR1R2 | CATTCCAATAATTTTCATTCC | |||

| mecR1F3 | TTATTTAGATCTAATTGAATATGG | 48510-49005 | 48 | 495 |

| mecR1R3 | TTTGCATTTGTATTTCTTC | |||

| mecIF1 | GGTTATGTTGAAACGAAAG | 48769-49406 | 51.6 | 637 |

| mecIR1 | GGTGTTATTACAAGCATTATTG |

GenBank accession number for designing primers and their locations, AP003129.

Colony PCR.

Briefly, a few bacterial cells were picked up with a sterile pipette tip by barely touching the tip to an isolated colony from a 24- to 48-h-old culture plate. The tip was inserted quickly into the PCR mixture tube until it touched the bottom of the tube and then removed quickly to prevent too many cells from sloughing off the tip. A 50-μl PCR mixture consisted of 25 μl of the HotStarTaq master mixture (QIAGEN, Inc.), 40 pmol each of forward and reverse primers, and 17 μl of water. The reaction mixture setup was subjected to an initial incubation at 95°C for 15 min to lyse cells and to activate the Taq polymerase, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s and at 48 to 53.5°C (Table 1) for 40 s and extension at 72°C for 60 s. A final extension reaction was carried out at 72°C for 7 min. The PCR products were resolved on 1.5% agarose gels to determine the quantity and quality of the amplification products. Occasionally, a second PCR was done to reamplify the target genes that failed to yield visible products after the first round of PCR. This was done by taking 1 to 5 μl from the first amplification reaction mixture as the template in a PCR setup that was otherwise identical to the one described above. The number of cycles was reduced to 20. The products were directly sequenced in either of the two DNA sequencers (ABI 3100 or ABI 377) with an ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit from Applied Biosystems.

Statistical analysis of mutations.

The frequency distribution (as a percentage) for single and multiple mutations in the three mec genes was determined. The statistical correlation, if any, between oxacillin resistance and either individual or combined mutations was also determined. The oxacillin resistance of strains with mutations was also compared with that of strains that did not contain any mutations in the mec complex. Since the distribution of the oxacillin MICs was skewed and not normally distributed, the median MIC (mMIC) for strains containing each mutation was used for comparison. Since synonymous mutations would not change the amino acid sequence, they were included in the no-mutation group for comparison. A P value of <0.005 was considered to be statistically significant. All the analyses were performed with SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.).

RESULTS

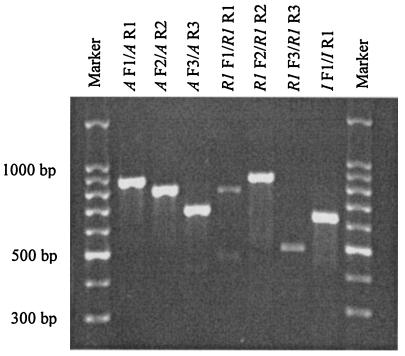

Seven primer pairs were used to amplify the three mec genes. Each of the primer pairs amplified a different but overlapping segment of the three mec genes. Each primer pair yielded a single major amplicon of the expected size. The amplicon sizes ranged from 495 to 870 bp, as shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

An ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel showing amplicons from the primers used in the present study. Primer pairs for the respective amplicons are listed at the top of each lane. DNA markers are loaded in the first and last lanes.

Identification of a new mec complex type.

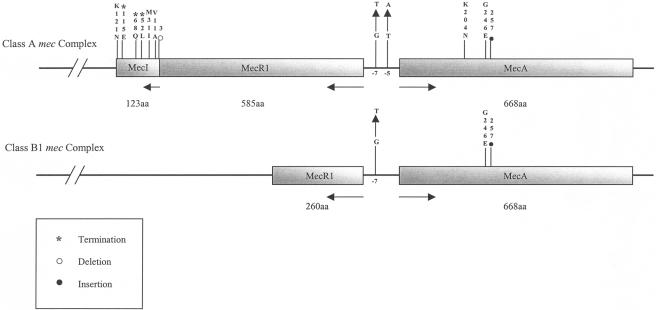

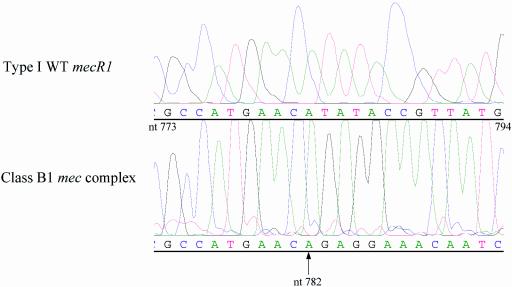

At the mec complex structure level, we identified two groups of MRSA isolates. The first group was represented by MRSA isolates that had all three mec genes with insertions, substitutions, or short deletions in the mec complex relative to the same sequence from the pre-MRSA strain N315 (5, 10). The second group of isolates (25.4% of 524 isolates examined) contained a major deletion in the mec complex whereby the entire mecI gene and roughly 45% of the mecR1 gene, including the penicillin-binding domain, were deleted (Fig. 2). The deletion was detected upon the repeated failure of primer sets mecIF1-mecIR1 (nt positions 48769 to 49406), mecR1F3-mecR1R3 (nt positions 48510 to 49005), and mecR1F2-mecR1R2 (nt positions 47706 to 48571) to give any PCR products for that group of isolates (Table 1). We identified the deletion junction by sequencing several amplicons from the primer set mecR1F1-mecR1R1 (nt positions 46981 to 47765) that covered the entire deletion region. The deletion site was located at nt position 782 in the mecR1 gene. Due to this deletion, the remaining 976 nt of mecR1, the entire mecI gene, and 30 nt beyond mecI were deleted (Fig. 3). A common set of four nucleotide bases (AACA) was found on either side of the deletion fragment. The positions were nt 779 to 782 in mecR1 and 30 to 33 nt downstream from the ends of the mecI genes. We classified this deletion type as a variant of the class B type (named B1) because we did not detect any IS1272 or IS431 sequences at the deletion junction of mecR1 (6, 9, 11).

FIG. 2.

(Top) Schematic diagram of the class A mec complex showing the mecA promoter-operator region and the MecA, MecR1, and MecI proteins with relevant nucleotide positions and amino acids where significant mutations were found. Transcriptional directions and the size of each protein are shown below the line diagram. (Bottom) Schematic diagram of the class B1 mec complex along with the mutation identified in this group of isolates.

FIG. 3.

Chromatogram showing the nucleotide position of the deletion junction in the mecR1 gene of the class B1 mec complex compared with the wild-type gene. The arrow at nt position 782 indicates the deletion junction.

Polymorphisms in the mec complex in Wisconsin MRSA strains.

Eighteen different mutations that included insertions, substitutions, deletions, and terminations were identified in the mec complex (Table 2). The number of independent mutations identified (excluding the class B1 type of deletion) in mecA, mecI, and mecR1 were eight, seven, and two, respectively. The percentages of each type of mutation shown in Table 2 were based on the number of isolates tested for that group of mutations in mec genes. The corresponding oxacillin MIC range is also listed for each group of mutations. In 34.7% of the isolates (total examined, 429), a G→T substitution at position 7 upstream of the mecA start site was detected. Only 0.23% of the isolates (total examined, 429) had a T→A substitution at position 5 upstream of the mecA start site. Four additional independent mutations in the mecA gene were identified. First, ∼2.2% of the isolates (total examined, 363) had a substitution mutation in codon 246 (GGA→GAA [G→E]). Four synonymous mutations were identified in mecA. They were at codons 415 (AAT→AAC [N→N], in 1.7%), 442 (AAC→AAT [N→N], in 3.9%), and 256 (GTT→GTG [V→V], in 13.2%). All isolates that had a T→G substitution at codon 256 on mecA also had a frameshift mutation due to the insertion of a cytosine at the first base of codon 257 (Fig. 2). This insertion created a premature termination codon at position 260 in mecA (Table 1). The mecR1 gene had two synonymous mutations at codons 117 (AGT→AGC [S→S], in 0.26%) and 583 (GAA→GAG [E→E], in 89.4%), respectively. Seven mutations were identified in the mecI gene. They were three substitutions, three terminations, and one deletion, as shown in Table 2. Two substitution mutations were at the N terminus, and the third mutation was at the C terminus of the deduced amino acid sequence. The substitutions were at codons 11 (GCA→GTA [A→V], in 0.78%), 31 (ATA→ATG [I→M], in 0.26%), and 121 (AAT→AAA [N→K], in 7.8%). Three stop-codon-generating mutations were at codons 52 (TTG→TAG, in 0.26%), 68 (CAA→TAA, in 0.26%), and 115 (GAA→TAA, in 0.78%). Except for the mutation at codon 68, none of these had been described previously.

TABLE 2.

List of mutations identified in the mec complex and corresponding ranges of oxacillin MICs

| mec complex or gene mutated | Mutation or nt position (codon and amino acid changes) | % of isolates with mutation (no. sequenced) | Oxacillin MIC range (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class B1 mec complex | mecI and partial mecR1 deletions | 25.4 (524) | 4->256 |

| mecA | 7 Upsa (G→T) | 34.7 (429) | 4->256 |

| 5 Upsb (T→A) | 0.23 (429) | >256 | |

| 204 (AAT→AAG, Asn→Lys) | 0.23 (429) | >256 | |

| 246 (GGA→GAA, Gly→Glu) | 2.2 (363) | 24->256 | |

| 256 (GTT→GTG, Val→Val)c | 13.2 (385) | 32->256 | |

| 300 (ACA→ACG, Thr→Thr) | 0.22 (462) | >256 | |

| 415 (AAT→AAC, Asn→Asn) | 1.7 (462) | >256 | |

| 442 (AAC→AAT, Asn→Asn) | 3.9 (462) | 128->256 | |

| mecR1 | 117 (AGT→AGC, Ser→Ser) | 0.26 (386) | >256 |

| 583 (GAA→GAG, Glu→Glu) | 89.4 (386) | 12->256 | |

| mecI | 3 (AAT, T deletion) | 0.52 (387) | 128->256 |

| 11 (GCA→GTA, Ala→Val) | 0.78 (387) | >256 | |

| 31 (ATA→ATG, Ile→Met) | 0.26 (387) | >256 | |

| 52 (TTG→TAG, Leu→STOP) | 0.26 (387) | >256 | |

| 68 (CAA→TAA, Gln→STOP) | 0.26 (387) | >256 | |

| 115 (GAA→TAA, Glu→STOP) | 0.78 (387) | 192->256 | |

| 121 (AAT→AAA, Asn→Lys) | 7.8 (387) | 16->256 |

Mutation 7 nt upstream from the start site.

Mutation 5 nt upstream from the start site.

C insertion at position 257 creates a TAA stop codon at position 260.

Statistical analysis of the relationship of strains containing major mec mutations with the corresponding oxacillin MICs.

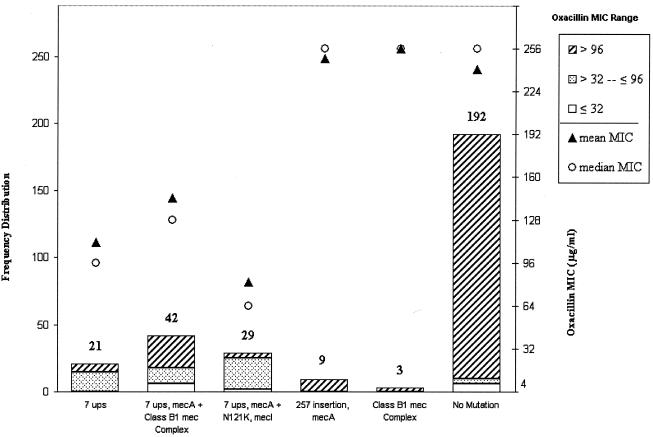

Out of the 18 mutation types, isolates containing the top five most frequent mutations or combinations of mutations (n = 104) in the three mec genes were chosen for correlation studies with isolates with no mutations (n = 192) (Fig. 4). Complete sequence data were available for the mec genes of these 296 isolates. The exclusive mutations tested were a 7-nt-upstream promoter mutation (7.1%), a cytosine insertion in codon 257 in mecA (3.04%), and a class B1 mec complex deletion type (1.0%), whereas the combination mutations tested were a 7-nt-upstream promoter mutation plus a class B1 mec complex deletion type (14.2%) and a 7-nt-upstream promoter mutation plus N121K in mecI (9.8%). For isolates carrying any given mutation, the oxacillin MICs had wide ranges. Since the MICs of oxacillin for different isolates with the same type of mutation were skewed, we chose the oxacillin mMICs to correlate with any one type or combination of mutations. The results of this correlation, which include frequency distribution of isolates for each type of mutation, mean MICs, and mMICs, are shown in Fig. 4. The mMICs for isolates with the 7-nt-upstream mutation, the 7-nt-upstream mutation plus N121K in mecI, and the 7-nt-upstream mutation plus the class B1 mec complex deletion were 111, 81, and 144 μg/ml (mean, 112 μg/ml), respectively, compared to 241 μg/ml for the isolates with no mutations. Clearly, the isolates that harbored a 7-nt-upstream mutation had significantly lower mMICs (mean, 112 μg/ml) than isolates that did not contain any mutation (P < 0.0001). This finding suggests that the promoter-operator region of mecA plays a more significant role in the overall resistance to oxacillin in MRSA. The mMICs for the isolates containing the mecA mutation involving an insertion at codon 257 and the class B1 mec complex were 248 and >256 μg/ml, respectively. These values were nearly identical to the mMICs for the no-mutation group of isolates and also were statistically not significant.

FIG. 4.

Histogram showing the frequency distribution (left y axis) of MRSA isolates with five nonsynonymous mutations in the mec complex. Each bar represents the frequency (number at the top of the bar) of isolates with either a single mutation or a combination of mutations. Also shown are the mean (filled triangles) and median (open circles) oxacillin MICs (right y axis) for isolates with each category of mutation. The differently shaded sections of each bar represent the frequencies of isolates for a given range of MICs, as shown in the key.

Clonal relationships of MRSA strains with different mutations in mec genes.

We analyzed the mutation data to see if the mutations were clonal in nature. The only relationship that could be identified was the link among the isolates with the 7-nt-upstream mutation, the class B1 mec complex deletion, and the type IV SCCmec. Out of 148 isolates that had the 7-nt-upstream promoter mutation, 85.1% belonged to a pulsed-field gel electrophoresis-based major clonal group, MCG-2. The remaining 13.9% isolates were distributed in three minor clonal groups. A major clonal group was defined as a clonal group that was represented by 5% or more of the total isolates, and a minor clonal group was one that was represented by less than 5% of the total isolates (data not shown). Sixty-four percent of the isolates harboring promoter mutations (n = 148) were of the class B1 mec complex type. The remaining isolates had nondisrupted mecR1 or mecI sequences. Interestingly, data were available for the SCCmec types and the promoter mutation of 61 isolates, and 97% of those isolates had the type IV SCCmec. There was no obvious clonality to the rest of the mutations.

DISCUSSION

Of the three mec complex genes, the mecI gene is reported to harbor the most mutations, probably because of the negative selection pressure this gene sustains to make MRSA strains resistant to methicillin. To some extent, it could also be due to the fact that this gene was probably more frequently studied than the other two mec genes. The previously described mutations in the mecI gene are substitutions at nt 22 (A→G), 32 (C→T), 43 (G→T), 116 (A→G), 125 (C→T), 142 (C→T), 152 (G→T), 163 (A→T), 202 (C→T), 260 (T→A), 343 (G→T), and 370 (T→A); insertions of an A at nt 64, 193, and 250; the insertion of a T at nt 91; and the deletion of a T at nt position 143 (9, 15-17). Several of these mutations would create either an amino acid substitution or a premature stop codon in MecI (9, 15, 17). The C→T change at nt 202 in mecI is one of the most commonly reported mutation types in isolates from the United States, Great Britain, and some other European countries (4, 9, 16, 18). However, this mutation was present in only 0.26% (total examined, 387) of the Wisconsin MRSA isolates. Since the six other mecI polymorphisms reported in this study were novel, this finding suggested that the Wisconsin MRSA strains might have evolved, both recently and locally. Besides mecI, we observed some rare nonsynonymous mutations in mecA and synonymous mutations in mecR1 genes that were present in less than 1% of the tested isolates (Table 2). The significance of these rare mutations in methicillin resistance may be better understood if additional strains containing these mutations are characterized.

The deletion junction identified in the class B1 mec complex is unique in that it lacks any insertion elements at the junction site. The presence of the four nucleotides (AACA) at the junction site suggests a plausible recombination event. This deletion type was primarily seen in MCG-2 and occasionally in minor clonal groups. The percentage of strains with the mecI-mecR1 deletion ranges from 16 to 73% globally (8, 9, 14, 16, 18). Our data show that 26% of the MRSA isolates collected in Wisconsin from 1989 to 1999 had a variant in the class B mec complex. There was no temporal trend in isolates with any particular mutation, and there was no evidence of any changes in the mutation rate during the study period. The isolates with the class B1 mec complex type of deletion were also interspersed with isolates containing polymorphisms in the mec genes over the study period.

Petinaki et al. (14) have described in their study of isolates from Patras, Greece, that 47% (n = 23) of the isolates for which the oxacillin MIC was low (≤128 μg/ml) were negative for the presence of mecI. However, we did not observe any such correlations with high or low oxacillin MICs. Kobayashi et al. have shown that the oxacillin MIC for an MRSA strain with a double mutation, a C→A change in the mecA promoter region and a C→T (Gln68→stop codon) change at position 202 in mecI, is not significantly different from that of an isolate containing a single mutation (9). In a study with a very limited number of strains, there was no correlation between the presence or deletion of mecI and a methicillin MIC of >128 μg/ml (16) We did observe that strains with the 7-nt-upstream promoter mutation in general had lower resistance than the strains with no mutation.

Another significant finding from this study was the observation that there was a high degree of conservation of the amino acid sequence of MecR1. The fact that the mecR1 gene function is conserved at the amino acid sequence level and that the substitutions, mutations, or deletions of mecI have no apparent effect on oxacillin resistance suggests that MecR1 may mediate methicillin resistance through intermediate factors other than MecI, as suggested by others (1). The simultaneous presence in isolates of the 7-nt-upstream mecA mutation and the class B1 mec type of deletion suggests that these two mutations coevolved. The fact that the majority of tested isolates with this combination mutation were present on the type IV SCCmec suggested a limited clonal source in Wisconsin MRSA isolates.

In conclusion, some important observations were made in this study of MRSA isolates from patients living in rural areas. First, several new polymorphisms in the three mec genes of MRSA have been identified. These newly identified polymorphisms can serve as evolutionary markers for MRSA from the midwestern United States and also aid in identifying their subclonal types. Second, the 7-nt-upstream mecA mutation seems to be an important mutation in determining methicillin resistance. Third, the significance of the AACA sequence at the deletion junction in mecR1 needs to be explored further.

Acknowledgments

S.K.S. acknowledges Sherri Strop for her contribution to mec complex sequencing for this project as a summer student in 2001. We also acknowledge Carla Schofield for data management, Mary Vandermause for help in reading oxacillin MICs, Po-Huang Chyou for statistical support, William Schwan for critically reading the manuscript, Graig Eldred for the Fig. 2 graphics, and Alice Stargardt for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

We acknowledge the Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation for its support through a grant-in-aid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archer, G. L., and J. M. Bosilevac. 2001. Signaling antibiotic resistance in staphylococci. Science 291:1915-1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger-Bachi, B., and S. Rohrer. 2002. Factors influencing methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Arch. Microbiol. 178:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers, H. F., and M. Sachdeva. 1990. Binding of beta-lactam antibiotics to penicillin-binding proteins in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 161:1170-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiramatsu, K. 1995. Molecular evolution of MRSA. Microbiol. Immunol. 39:531-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, and K. Hiramatsu. 1999. Cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the entire mec DNA of pre-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus N315. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1449-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katayama, Y., T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Genetic organization of the chromosome region surrounding mecA in clinical staphylococcal strains: role of IS431-mediated mecI deletion in expression of resistance in mecA-carrying, low-level methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1955-1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katayama, Y., H.-Z. Zhang, and H. F. Chambers. 2004. PBP 2a mutations producing very-high-level resistance to beta-lactams. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:453-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi, N., K. Taniguchi, K. Kojima, S. Urasawa, N. Uehara, Y. Omizu, Y. Kishi, A. Yagihashi, I. Kurokawa, and N. Watanabe. 1996. Genomic diversity of mec regulator genes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Epidemiol. Infect. 117:289-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi, N., K. Taniguchi, and S. Urasawa. 1998. Analysis of diversity of mutations in the mecI gene and mecA promoter/operator region of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrobiol. Agents Chemother. 42:717-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim, T. T., G. W. Coombs, and W. B. Grubb. 2002. Genetic organization of mecA and mecA-regulatory genes in epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Australia and England. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:819-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinney, T. K., V. K. Sharma, W. A. Craig, and G. L. Archer. 2001. Transcription of the gene mediating methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (mecA) is corepressed but not coinduced by cognate mecA and β-lactamase regulators. J. Bacteriol. 183:6862-6868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1999. Standard M100-S9. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 9th supplement, vol. 19. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 14.Petinaki, E., A. Arvaniti, G. Dimitracopoulos, and I. Spiliopoulou. 2001. Detection of mecA, mecR1, and mecI genes among clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant staphylococci by combined polymerase chain reactions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:297-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosato, A. E., W. A. Craig, and G. L. Archer. 2003. Quantitation of mecA transcription in oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J. Bacteriol. 185:3446-3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki, E., K. Kuwahara-Arai, J. F. Richardson, and K. Hiramatsu. 1993. Distribution of mec regulator genes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus clinical strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1219-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandenesch, F., T. Naimi, M. C. Enright, G. Lina, G. R. Nimmo, H. Heffernan, N. Liassine, M. Bes, T. Greenland, M. E. Reverdy, and J. Etienne. 2003. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:978-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weller, T. M. 1999. The distribution of mecA, mecR1 and mecI and sequence analysis of mecI and the mec promoter region in staphylococci expressing resistance to methicillin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]