Abstract

Penicillin resistance threatens the treatment of pneumococcal infections. We used sentinel hospital surveillance (1978 to 2001) and population-based surveillance (1995 to 2001) in seven states in the Active Bacterial Core surveillance of the Emerging Infections Program Network to document the emergence in the United States of invasive pneumococcal isolates with very-high-level penicillin resistance (MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml). Very-high-level penicillin resistance was first detected in 1995 in multiple pneumococcal serotypes in three regions of the United States. The prevalence increased from 0.56% (14 of 2,507) of isolates in 1995 to 0.87% in 2001 (P = 0.03), with peaks in 1996 and 2000 associated with epidemics in Georgia and Maryland. For a majority of the strains the MICs of amoxicillin (91%), cefuroxime (100%), and cefotaxime (68%), were ≥8 μg/ml and all were resistant to at least one other drug class. Pneumonia (50%) and bacteremia (36%) were the most common clinical presentations. Factors associated with very highly resistant infections included residence in Tennessee, age of <5 or ≥65 years, and resistance to at least three drug classes. Hospitalization and case fatality rates were not higher than those of other pneumococcal infection patients; length of hospital stay was longer, controlling for age. Among the strains from 2000 and 2001, 39% were related to Tennessee23F-4 and 35% were related to England14-9. After the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, the incidence of highly penicillin resistant infections decreased by 50% among children <5 years of age. The emergence, clonality, and association of very-high-level penicillin resistance with multiple drug resistance requires further monitoring and highlights the need for novel agents active against the pneumococcus.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a leading bacterial cause of meningitis, community-acquired pneumonia, sepsis, and otitis media in the United States. The incidence of pneumococcal disease is particularly high among young children and the elderly, where S. pneumoniae contributes importantly to morbidity and mortality. Before therapy was available for pneumococcal infections, approximately 80% of patients hospitalized with bacteremic pneumococcal infections died of their illness. With effective antimicrobial agents, mortality has improved but remains at nearly 20% for bacteremic disease in older adults (31).

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance threatens the successful treatment of pneumococcal infections. In 1998, 24% of all invasive pneumococcal isolates captured by a multistate, population-based surveillance network were resistant to penicillin, and 14% of all isolates were resistant to three or more drug classes (31). The clinical impact of antibiotic resistance has been clearly demonstrated for pneumococcal meningitis (18) and for otitis media (5, 6, 8, 15). Evidence for a relationship between resistance and pneumonia treatment failures is less clear, although studies suggest that case fatality rates may be higher for pneumococcal pneumonia caused by strains with elevated resistance to penicillin (10).

In addition to the emergence of resistance to newer drug classes such as the fluoroquinolones (3), the evolution of strains with resistance to higher concentrations of antimicrobial agents raises cause for concern. Among invasive pneumococcal isolates, strains of intermediate susceptibility predominated in the United States in the 1980s. Penicillin resistance (MICs ≥ 2 μg/ml) emerged during this time period (27) and steadily increased to represent approximately 60% of all invasive pneumococcal isolates in 1998 (31). Moreover, in pneumococci penicillin resistance strongly correlates with resistance to other drug classes (31).

In this report, we use data from national sentinel and population-based surveillance for invasive pneumococcal disease to document the emergence of pneumococci with very-high-level resistance to penicillin (penicillin MIC of ≥8 μg/ml) in the United States in the 1990s. We evaluate risk factors for infection with these very highly resistant strains among patients with invasive pneumococcal disease, clinical characteristics of disease, and evidence for a clinical impact of resistance. Additionally, we evaluate the clonal relatedness of very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains from 2000 and 2001.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sentinel surveillance.

Laboratory-based surveillance for invasive pneumococcal infections was established at 44 hospitals in 26 states in 1978 (2). These included community hospitals, federal hospitals, municipal or county hospitals, and hospitals with university affiliations. This surveillance continued through 1994 although participating hospitals varied over time. Participating hospitals were asked to submit all pneumococci isolated from blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or other normally sterile specimens to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where they were confirmed as pneumococci based on optochin or ethylhydrocuprein susceptibility and bile solubility. From 1978 to 1987, antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the agar microdilution method (29). All strains that grew at penicillin concentrations of 0.12 μg/ml were further evaluated to determine the exact MIC for the strains. Starting in 1991, broth microdilution was used and penicillin wells with concentrations of up to 8 μg/ml were included on susceptibility test panels (1).

Population-based surveillance.

The Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) of the Emerging Infections Program Network, a core component of the CDC's Emerging Infections Program, is an active, population-based, laboratory-based surveillance system. All surveillance areas that monitored for invasive pneumococcal infections from 1995 through 2001 were included in the overall analysis: Portland, Oregon (3 counties starting in July 1995); California (3 San Francisco Bay area counties for the first three quarters of 1995, and San Francisco County only thereafter, with the addition of Contra Costa and Alameda counties in October 2000 for children <5 years of age); Denver, Colorado (5 counties beginning in July 2000); Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota (7 counties staring in April 1995); the Baltimore metropolitan area, Maryland (starting in January 1995); Atlanta, Georgia (8 metro counties starting in January 1995; expanded to 20 metro area counties in January 1997); selected urban areas of Tennessee (5 counties staring in January 1995; expanded to 11 counties in August 1999); upstate New York (7 Rochester area counties starting in July 1997; expanded to include 8 Albany area counties starting in January 1999); and the state of Connecticut (starting in March 1995). The total population under surveillance in 2000 was over 21 million persons, based on U.S. Census Bureau data.

Analyses of trends over time were limited to those surveillance counties that had continuous surveillance from 1996 through 2001. For the year 2000 this represented 16,203,806 people, including 1,094,954 children less than 5 years of age and 1,767,071 people ≥65 years of age.

A case of invasive pneumococcal disease was defined as isolation of S. pneumoniae from a normally sterile body fluid (e.g., blood, cerebrospinal, peritoneal, joint, or pleural fluid) from a surveillance area resident. To identify cases, surveillance personnel periodically contacted all clinical microbiology laboratories in their areas. Periodic audits of laboratory records were conducted at least every 6 months to ensure complete reporting. Case-patient information was collected by using a standardized questionnaire that included demographic data, clinical syndrome, and disease outcome.

Pneumococcal isolates were sent to reference laboratories for serotyping based on the Quellung reaction. Isolates from Minnesota were tested at the Minnesota Department of Health laboratory, and all others were tested at the CDC. Isolates underwent susceptibility testing by broth microdilution according to NCCLS methods (23); testing was performed at the CDC, the Minnesota Department of Public Health, or the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Although the drugs included in susceptibility panels varied somewhat by year, panels in all years included penicillin wells with concentrations of up to 16 μg/ml.

Disease incidence rates were calculated by using population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau; for cases in 2001, data from the 2000 census were used.

Molecular epidemiology.

Isolates from 2000 and 2001 (n = 79) were fingerprinted by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Briefly, genomic DNA was prepared in situ in agarose blocks as described previously (19, 21) and was digested with SmaI (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). The fragments were resolved by PFGE in 1% agarose (SeaKem GTG agarose; BioWhittaker Molecular Applications, Rockland, Maine) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 14°C at 6 V/cm in a CHEF-DR III system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The parameters in block 1 were an initial pulse time of 1 s, increased to 30 s for 17 h, and in block 2, the initial pulse time was 5 s, increased to 9 s for 6 h. Fingerprint patterns were compared by using BioNumerics (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) analysis software and related to 26 international clones described by the Pneumococcal Molecular Epidemiology Network (reference 22 and www.pneumo.com). A dendrogram based on the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages was constructed by using the Dice similarity coefficient and a band tolerance position of 1.5%. Based on PFGE clustering, 17 isolates were selected for MLST analysis as described previously (9, 11). Internal fragments of the aroE, gdh, gki, recP, spi, xpt, and ddl genes were amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA, and the fragments were directly sequenced in each direction by using the primers that were used for the initial amplification. The sequences (alleles) at each locus were compared to those at the MLST website (www.mlst.net) and were assigned allele numbers if they corresponded to sequences already submitted to the MLST database; novel sequences were submitted for new allele numbers and deposited in the database. The allele numbers at the seven loci were compared to those at the MLST website, and sequence types (STs) were assigned. Allelic profiles that were not represented in the MLST database were submitted for assignment of new ST numbers and deposited in the database.

Definitions.

Isolates were defined as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant according to 2003 NCCLS definitions (23). Strains for which the penicillin MICs range from 2 to 4 μg/ml are considered resistant, and strains for which the penicillin MIC is ≥8 μg/ml are considered very highly resistant or as having very-high-level resistance. For cefotaxime, nonmeningitis breakpoints were applied to strains that did not cause meningitis unless otherwise specified. Strains that were intermediate or resistant to three or more drug classes were considered multiply resistant. Pneumococcal isolates were considered vaccine-type strains if they were of the serotypes included in the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F).

Underlying conditions predisposing patients to pneumococcal infection were defined according to present Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommendations for pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine and included cancer, renal insufficiency, human immunodeficiency virus infection, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, sickle cell disease, cirrhosis, alcoholism, congestive heart failure, and patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapies. Infections where pneumococci were isolated after greater than 2 days of hospital admission were considered nosocomial; all others were community acquired.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS version 8.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.). The chi-square test for trend was used to assess linear trends over time. We used the chi-square and Fisher exact tests to compare proportions. Univariate analysis used for variables with more than two levels and multivariable analyses were performed by using logistic regression. Multivariable models were evaluated by starting with all factors that were significant at a P of <0.15 in univariate analysis and dropping nonsignificant factors in a backwards, stepwise fashion. All two-way interactions in final multivariable models were evaluated. Throughout, two-sided P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are reported.

RESULTS

Sentinel surveillance.

As part of the pneumococcal sentinel surveillance system, 7,862 isolates were tested by the CDC for antimicrobial susceptibility between 1978 and 2001. Participation in this network decreased in the early 1990s; the numbers of hospitals reporting cases and of isolates tested for susceptibility over time are shown in Table 1. None of the isolates tested for susceptibility had very-high-level resistance to penicillin.

TABLE 1.

Pneumococcal isolates collected as part of national sentinel surveillance for invasive pneumococcal disease, 1978 to 2001

| Years | No. of hospitals that reported cases | No. of cases reported | No. of isolates tested for susceptibility to penicillin | % of isolates nonsusceptible to penicillin (% of isolates resistant to penicillin)a | % of isolates with very-high-level resistance to penicillinb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978-1979 | 40 | 1,059 | 592 | 1 (0) | 0 |

| 1980-1984 | 49 | 3,765 | 3,041 | 4 (0) | 0 |

| 1985-1989 | 52 | 4,566 | 2,162 | 3 (0) | 0 |

| 1990-1994 | 38 | 4,003 | 1,372 | 11 (2) | 0 |

| 1995-1999 | 34 | 2,822 | 608 | 18 (7) | 0 |

| 2000-2001 | 9 | 418 | 87 | 8 (1) | 0 |

| Total | 103 | 16,633 | 7,862 | 6 (1) | 0 |

Nonsusceptibility to penicillin was defined as intermediate susceptibility or resistance according to NCCLS 2003 breakpoints (23); for strains resistant to penicillin the MIC was ≥2 μg/ml.

Very-high-level penicillin resistance was defined as a minimum inhibitory concentration of ≥8 μg/ml.

Population-based surveillance.

From 1995 to 2001 active surveillance identified 28,434 cases of invasive pneumococcal disease. Isolates were available for susceptibility testing from 84% (23,996) of cases; the availability of isolates was similar across surveillance areas (California, 75; Colorado, 82; Connecticut, 93; Georgia, 83; Maryland, 86; Minnesota, 92; New York, 88; Oregon, 81; and Tennessee, 74%).

Among isolates with susceptibility results, the penicillin MIC for 1% (225 of 23,996) was 8 μg/ml. No strains were identified for which the penicillin MIC was greater than 8 μg/ml.

Trends over time.

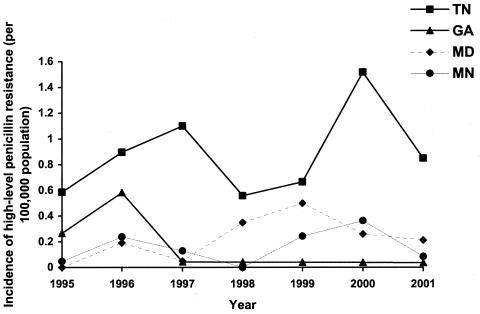

In 1995, very-high-level penicillin-resistant pneumococci were identified in California, Minnesota, Tennessee, and Georgia. By 1997 all additional participating areas had identified at least one invasive pneumococcal case due to a highly resistant isolate. However, highly resistant strains were predominantly (48%, or 107 of 225) from Tennessee. In areas with continuous surveillance from 1995 through 2001, the proportion of isolates with very-high-level resistance to penicillin increased significantly from 0.56% of isolates in 1995 to 0.87% of isolates in 2001 (χ2 for linear trend, 4.68; P = 0.03), although the prevalence varied widely from year to year with peaks in 1996 (1.2%) and 2000 (1.7%). Within surveillance areas, discrete outbreaks predominantly of a single serotype appeared to occur (Fig. 1). For example, in Georgia, very-high-level penicillin resistance peaked in 1996; 12 of 13 very highly resistant strains were of serotype 23F. Among penicillin nonsusceptible isolates (isolates for which the penicillin MICs were ≥0.1 μg/ml), the proportion of isolates with very-high-level penicillin resistance did not increase significantly from 1995 to 2001 (χ2 for linear trend, 1.4; P = 0.24).

FIG. 1.

Incidence of very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains (penicillin MIC of ≥8 μg/ml) among selected areas from ABCs, 1995 to 2001.

By using the prevalences in 1998 and 1999 as a baseline before a seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-7) was available in the United States, the proportion of isolates with very-high-level penicillin resistance more than doubled from 1998 and 1999 to 2000 and then fell by close to 50% from 2000 to 2001. The incidence of very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains fell by 19% from 0.21 per 100,000 population in 1998 and 1999 to 0.16 per 100,000 in 2001. Among children less than 5 years of age, the incidence dropped by 50%, from 1.49 per 100,000 to 0.74 per 100,000.

In Tennessee, the surveillance area with a predominance of very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains (3.8%), serotype data were available starting in 1995. In 1995, strains with very-high-level penicillin resistance were identified in two counties and belonged to three serotypes (23F, 14, and 6B). An additional serotype, 6A, was only detected once, in 2001. Otherwise, these three very-high-level resistant serotypes circulated in Tennessee and were ultimately found in 10 of 11 surveillance area counties.

Clinical characteristics of very-high-level penicillin-resistant pneumococcal infections.

The majority of infections due to very-high-level penicillin-resistant pneumococci presented as bacteremic pneumonia (50%, or 113 of 226), primary bacteremia (36%, or 81 of 226), and meningitis (6%, or 14 of 226); greater than 98% of infections were community acquired. Underlying conditions predisposing to pneumococcal infection were common among this population (44%). As with other pneumococcal infections, a disproportionate number of cases occurred among children <5 years of age and among the elderly (24 and 29%, respectively); 9.7% (22 of 226) of infected patients died. Over half of pneumococcal infections caused by very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains (52%, or 109 of 210 strains with known serotype) belonged to serotype 23F; 32% (68 of 210) were type 14. The remainder was distributed among types 6A, 6B, 9V, 19A, and 19F. All strains were resistant to at least one other drug class; 55% were resistant to at least three drug classes.

Factors associated with very-high-level penicillin-resistant pneumococcal infections.

Resistance to at least three drug classes and residence in Tennessee were the two strongest risk factors in both univariate and multivariable analyses with adjusted odds ratios (OR) of 5.5 (4.1 to 7.2) and 5.4 (4.1 to 7.1), respectively. Compared to adults aged 18 to 64 years, children less than 5 years of age were at the greatest risk of infection with these strains (adjusted OR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.5) as were adults of ≥65 years (adjusted OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.0 to 2.0). In multivariable analysis, infection with very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains was not associated with clinical syndrome or route of acquisition (nosocomial versus community). Additionally, patients with highly penicillin-resistant pneumococcal infections did not differ from other patients with invasive pneumococcal infections in terms of race, sex, or prevalence of underlying conditions recognized as predisposing patients to pneumococcal infection.

When analyses were limited to the subset of strains that were penicillin nonsusceptible (n = 5,894), the only factors significantly associated with very-high-level penicillin resistance were residence in Tennessee and age of less than 5 years; these remained significant in multivariable analysis.

The serotype could not be analyzed in the primary models because data were only routinely available from 1998 to 2001. For the subset of isolates where the serotype was available, strains for which the penicillin MICs were very high were significantly more likely than other penicillin-nonsusceptible strains to belong to serotype 23F (52 versus 7%; χ2 = 582; P < 0.001) or serotype 14 (32 versus 17%; χ2 = 32.6; P < 0.001).

Antimicrobial susceptibility characteristics.

In contrast to other penicillin nonsusceptible pneumococci, all strains with very-high-level resistance to penicillin were resistant to at least one other drug class (100 versus 83%; χ2 = 36.1; P < 0.001). Multidrug resistance, defined as resistance to three or more drug classes, was not more common among very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains than among other penicillin-nonsusceptible strains (55 versus 57%); moreover, among multidrug-resistant strains, very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains were not more likely to be resistant to more drug classes. The MICs for all strains with very-high-level penicillin resistance were elevated compared to the MICs of the other β-lactam agents tested (Table 2). In particular, amoxicillin MICs for 91% of strains (198 of 218) were ≥8 μg/ml, cefotaxime MICs for 68% of strains (152 of 225) were ≥8 μg/ml, and cefuroxime MICs for 100% of strains (225 of 225) were ≥8 μg/ml. In contrast, 90% (203 of 225) of strains with very-high-level penicillin resistance were susceptible to clindamycin, and 86% (194 of 225) were susceptible to tetracycline.

TABLE 2.

Proportion of pneumococcal isolates resistant to various antimicrobial agents according to their susceptibility to penicillin, 1995 to 2001

| Agent | MIC threshold (μg/ml) | % of isolates by degree of penicillin susceptibilitya (no. of isolates tested)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Intermediate susceptibility | Resistant | Very-high-level resistance | ||

| Amoxicillin | ≥8b | 0 (16,855) | 0.1 (2,148) | 21.9 (2,946) | 90.8 (218) |

| Cefotaxime | ≥2b | 0.01 (18,102) | 2.8 (2,486) | 34.6 (3,182) | 97.8 (225) |

| ≥8 | 0 (18,102) | 1.1 (2,486) | 2.9 (3,182) | 67.6 (225) | |

| Cefuroxime | ≥2b | 0.1 (11,638) | 42.2 (1,660) | 99.5 (2,324) | 100 (144) |

| ≥8 | 0.01 (11,638) | 3.0 (1,660) | 65.2 (2,324) | 100 (145) | |

| Meropenem | ≥1b | 0.01 (18,102) | 0.6 (2,486) | 48.5 (3,182) | 97.8 (225) |

| Erythromycin | ≥1b | 3.9 (18,102) | 38.4 (2,486) | 66.4 (3,182) | 54.7 (225) |

| ≥8 | 2.6 (18,102) | 25.5 (2,486) | 55.3 (3,182) | 48.0 (225) | |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≥4/≥76b | 6.2 (18,102) | 50.6 (2,486) | 92.4 (3,182) | 96.4 (225) |

| Tetracycline | ≥8b | 1.6 (18,102) | 3.9 (2,486) | 27 (3,182) | 13.8 (225) |

| Levofloxacin | ≥8b | 0.2 (10,916) | 0.3 (1,465) | 0.9 (2,187) | 1.4 (143) |

| Clindamycin | ≥1b | 0.6 (18,102) | 9.5 (2,486) | 14.9 (3,182) | 9.8 (225) |

| ≥8 | 0.03 (18,102) | 6.4 (2,486) | 10.2 (3,182) | 7.1 (225) | |

Penicillin susceptibility was defined according to NCCLS breakpoints for 2003 (23) as follows: susceptible, MIC < 0.06 μg/ml; intermediate susceptibility, MIC of 0.12 to 1.0 μg/ml; resistance, MIC of 2 to 4 μg/ml; very-high-level resistance, MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml. Susceptibility test panels varied from year to year, and so not all isolates were tested against the same panel of antimicrobial agents.

Threshold for resistance according to NCCLS breakpoints for 2003 (23); the meningitis breakpoint for cefotaxime is shown.

Two strains (of 143 strains tested) very highly resistant to penicillin were resistant to levofloxacin. One of these isolates was additionally resistant to amoxicillin, cefotaxime, cefuroxime, clindamycin, cotrimoxazole, erythromycin, and meropenem. This strain infected a 40-year-old male with no underlying conditions who had a focal joint infection that did not require hospitalization. The other isolate was additionally resistant to amoxicillin, cefuroxime, cotrimoxazole, erythromycin, and meropenem and was susceptible to cefotaxime. This strain caused bacteremic pneumonia in an 84-year-old female nursing home resident with underlying immunocompromising conditions. She was hospitalized for 11 days and survived the infection.

Clinical impact of resistance.

Patients with very-high-level penicillin-resistant infections were not more likely than other pneumococcal case patients to be hospitalized. They were also not more likely to die of their infections (9.7 versus 10.5%); controlling for age and race, case fatality was not higher for very-high-level penicillin-resistant infections (OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.7 to 1.7). However, among hospitalized patients (18,766, or 78% of patients), the mean length of hospital stay (available for 89% of hospitalized patients) was significantly longer for patients with highly resistant pneumococcal infections, when controlling for age (for children <18 years of age: 8.7 versus 6.6 days, Kruskal-Wallis χ2 [df 1] = 9.7, P = 0.002; for adults ≥18 years of age: 12.0 days versus 9.1 days, Kruskal-Wallis χ2 [df 1] = 5.92, P = 0.02).

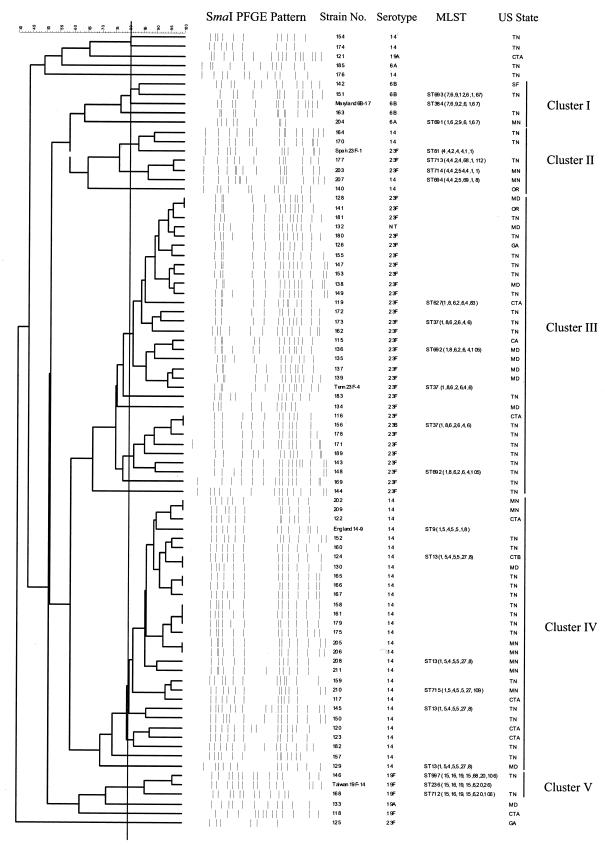

Molecular epidemiology of very-high-level penicillin-resistant isolates.

The PFGE fingerprint patterns and clustering of the 79 isolates from 2000 to 2001 and relatedness to 26 international clones are shown in Fig. 2. The majority of isolates (n = 70; 88%) were assigned to one of five clusters based on PFGE patterns and MLST data (clusters I to V). Isolates assigned to cluster I by PFGE (n = 4; 5%) were related to Maryland6B-17, and analysis of the seven housekeeping genes of two of these isolates (strains 151 and 204) revealed novel sequence types (ST691 and ST693) which are single-locus variants (SLV) of the type clone. All isolates (n = 5; 6%) belonging to the major Spain23F-1 clone showed unique STs that differed at 1, 2, or 3 loci from the type strain (ST81). Thirty-one isolates (39%) were related to Tennessee23F-4 (ST37 cluster III), and five isolates chosen for MLST were identical to or SLVs of ST37. Two isolates (136 and 148) had identical novel ddl sequences (allele 105), resulting in new ST692. Cluster IV included 28 isolates (35%) related to the England14-9 clone by PFGE and MLST. Representative cluster IV isolates were SLVs or double-locus variants of this type strain. All isolates (n = 4; 12.5%) related to the major Spain23F-1 clone yielded unique STs and differed at 1, 2, or 3 loci from the type strain (ST81). Two serotype 19F isolates (168 and 146) were SLVs and double locus variants of the Taiwan19F-14 clone. They both shared a unique ddl sequence that is identical to a Streptococcus oralis ddl allele.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram (genetic relatedness) and PFGE fingerprint patterns for 79 isolates analyzed from 2000 to 2001 and relatedness to 26 international clones. Strain code, serotype, antibiotic susceptibility profile, MLST sequence type, and state of isolation are given (on the right). Clusters I through V are isolates showing ≥80% similarity by PFGE to one of the international clones.

DISCUSSION

Invasive disease caused by very-high-level penicillin-resistant pneumococci emerged in the United States in 1995 and increased in prevalence through 2001 although it remained at <1% of invasive pneumococcal strains except in Tennessee. Very-high-level penicillin resistance is associated with high (≥8 μg/ml) amoxicillin, cefuroxime, and cefotaxime MICs, and all highly penicillin-resistant strains were resistant to at least one additional drug class. Two multidrug-resistant strains that were also resistant to levofloxacin raise concern about the ever-narrowing therapy options for resistant pneumococcal infections.

When first detected in 1995, very highly resistant strains already belonged to multiple serotypes and were present in three regions of the United States (west, southeast, and midwest), although strains predominated in Tennessee. The high degree of clonality of these strains suggests local dissemination in focal areas of the United States. Our data suggest multiple, independent origins of very-high-level penicillin resistance and are consistent with molecular analyses suggesting that recently circulating strains belong to at least five clonal groups, although clusters related to Tennessee23F-4 and to England14-9 clearly predominated. The reference strain for Tennessee23F-4, first described in the early 1990s, is a penicillin-intermediate (MIC of 0.12 μg/ml) and very-high-level cefotaxime-resistant (MIC of 32 μg/ml) isolate. This specific resistance phenotype is characterized by a Thr-550-Ala substitution in the pbp2x gene which provides increased resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins but a loss of resistance to penicillin (4). The strains in this study have evolved to very high penicillin MICs (8 μg/ml) and various levels of cefotaxime resistance (MICs of 1 to 16 μg/ml), and analysis of the pbp genes should provide insight into the mechanism of this increased resistance. The reference strain for the England14-9 clone is an erythromycin-resistant isolate first described in the United Kingdom in the 1990s (12), and strains belonging to this clone continue to be isolated in many parts of Europe. The strains in this study belonging to the England14-9 clone are all multidrug resistant, suggesting that in the past decade this clone has evolved resistance to various classes of antibiotics in the United States. The emergence of very-high-level penicillin resistance in the globally disseminated Spain23F-1 and Taiwan19F-14 clones and in the Maryland6B-17 clone emphasize the need for continued surveillance since these international clones have contributed to the rapid increase in resistance to many classes of antibiotics worldwide (11).

The ddl locus from S. oralis in two of these strains suggests that the origin of very-high-level resistance in some strains may result from the transformation and incorporation of resistance determinants from viridans group streptococci. Little is known about the molecular basis of very-high-level penicillin resistance in pneumococci. A pneumococcus for which the penicillin MIC is 16 μg/ml was identified in Hungary from 1997 to 1998 (28). The cefotaxime MIC for that strain was 4 μg/ml. The very high (MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml) amoxicillin and cefotaxime MICs for the strains isolated in the United States are reminiscent of the high amoxicillin MICs for novel strains recently described in France (7). In that study the penicillin, amoxicillin, and cefotaxime MICs were as high as 8 μg/ml for only two strains isolated from the middle ear and nasopharynx of children. There has been no description to date of the risk factors for the emergence of very-high-level penicillin-resistant pneumococci.

Among patients with highly penicillin-resistant invasive infections, there was no strong evidence of a clinical impact of resistance, although among hospitalized patients the mean length of stay was longer, suggesting the possibility of a more difficult treatment course. The clinical impact of pneumococcal resistance, particularly for the case of nonmeningeal syndromes where high antibiotic concentrations can typically be achieved, has been difficult to characterize (10, 15, 30). We were further limited by a lack of information on the antimicrobial therapies patients received and of detail on illness severity and underlying conditions. It is also possible that we did not detect a clinical impact of resistance because penicillin is no longer used as a first-line treatment. However, there is no evidence that ceftriaxone or cefotaxime, common first-line therapies for pediatric pneumococcal infections, can effectively treat nonmeningitis infections caused by strains for which the MICs are ≥8 μg/ml (16, 25), as was common among very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains. Recent reports that some penicillin-resistant pneumococci are less susceptible to cefotaxime than to ceftriaxone (17) raise the possibility that ceftriaxone MICs, which were not measured in this study, remained in a therapeutic range.

Lack of a clinical impact of resistance may also result from the impaired virulence of very highly resistant strains. Characterization of the genetic mechanism of very-high-level penicillin resistance may shed light on this issue. Fitness costs associated with resistance are not uncommon, but adaptations compensating for these costs often evolve (20, 24, 26).

Although the prevalence of highly penicillin-resistant invasive isolates increased from 1995 to 2001, fluctuations from year to year and the overall low annual prevalence (<2% at its maximum) (Fig. 1) do not suggest rapid spread of this resistance profile but, rather, local dissemination of resistant clones. Moreover, the newly licensed pneumococcal conjugate vaccine may be effective at limiting the spread of very-high-level penicillin-resistant strains. The majority of very highly resistant strains occurred in vaccine-included serotypes, particularly 23F and 14. Moreover, the prevalence of very-high-level penicillin resistance, particularly among young children, declined in 2001 following vaccine introduction.

Selective pressures favoring the emergence and spread of very-high-level penicillin resistance remain unclear. It is likely that the association of very-high-level penicillin resistance with resistance to other drugs played a role. While the United States and some other developed countries have experienced shifts towards higher penicillin MICs (31), in many developing countries, including South Africa where fully resistant pneumococci were first described in 1978 (14), intermediate penicillin resistance continues to predominate (13). The emergence of pneumococci with very-high-level penicillin resistance poses a further challenge to the medical community to develop novel agents active against the increasingly resistant pneumococcus.

Acknowledgments

Members of the ABCs team include the following: P. Cieslak, N. Bennett, M. Farley, J. Hadler, L. Harrison, R. Lynfield, and W. Schaffner. The following ABCs members assisted with data collection and management: B. Barnes, N. Barrett, W. Baughman, J. Besser, S. Crawford, P. Daily, L. Fulcher, A. Glennen, S. Johnson, B. Juni, C. Lexau, Z. Li, L. McElmeel, T. Pilishvili, V. Sakota, L. Sanza, A. Schuchat, L. Sheeley, T. Skoff, G. Smith, K. Stefonek, C. Van Beneden, C. Wright, and E. Zell.

This study was supported by funds from the CDC/National Center for Infectious Diseases Emerging Infections Program Network and Antimicrobial Resistance Working Group, the National Vaccine Program Office, and the CDC Opportunistic Infections Working Group. The molecular epidemiology work conducted at Emory University was supported by a grant from Roche Laboratories to K.K. and L.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Breiman, R. F., J. C. Butler, F. C. Tenover, J. A. Elliott, and R. R. Facklam. 1994. Emergence of drug-resistant pneumococcal infections in the United States. JAMA 271:1831-1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler, J. C., J. Hofmann, M. S. Cetron, J. A. Elliott, R. R. Facklam, R. F. Breiman, et al. 1996. The continued emergence of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's pneumococcal sentinel surveillance system. J. Infect. Dis. 174:986-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, D. K., A. McGeer, J. C. de Azavedo, D. E. Low, and the Canadian Bacterial Surveillance Network. 1999. Decreased susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae to fluoroquinolones in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 341:233-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey, T. J., M. Daniels, L. K. McDougal, C. G. Dowson, F. C. Tenover, and B. G. Spratt. 1995. Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1306-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagan, R., O. Abramson, E. Leibovitz, R. Lang, S. Goshen, D. Greenberg, P. Yagupsky, A. Leiberman, and D. M. Fliss. 1996. Impaired bacteriologic response to oral cephalosporins in acute otitis media caused by pneumococci with intermediate resistance to penicillin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 15:980-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dagan, R., E. Leibovitz, A. Leiberman, and P. Yagupsky. 2000. Clinical significance of antibiotic resistance in acute otitis media and implication of antibiotic treatment on carriage and spread of resistant organisms. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:S57-S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doit, C., C. Loukil, F. Fitoussi, P. Geslin, and E. Bingen. 1999. Emergence in France of multiple clones of clinical Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates with high-level resistance to amoxicillin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 4:1480-1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowell, S. F., J. C. Butler, G. S. Giebink, M. R. Jacobs, D. Jernigan, D. M. Musher, A. Rakowsky, and B. Schwartz. 1999. Acute otitis media: management and surveillance in an era of pneumococcal resistance-a report from the Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Therapeutic Working Group. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:1-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enright, M. C., and B. G. Spratt. 1998. A multilocus sequence typing scheme for Streptococcus pneumoniae: identification of clones associated with serious invasive disease. Microbiology 144:3049-3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feikin, D. R., A. Schuchat, M. Kolczak, J. Hadler, L. H. Harrison, L. Lefkowitz, et al. 2000. Mortality from invasive pneumococcal pneumonia in the era of antibiotic resistance, 1995-1997. Am. J. Public Health 90:223-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gertz, R. J., M. McEllistrem, D. Boxrud, Z. Li, V. Sakota, T. Thompson, R. Facklam, J. Besser, L. Harrison, C. Whitney, and B. Beall. 2003. Clonal distribution of invasive pneumococcal isolates from children and selected adults in the United States prior to 7-valent conjugate vaccine introduction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4194-4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall, L. M., R. A. Whiley, B. Duke, R. C. George, and A. Efstratiou. 1996. Genetic relatedness within and between serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae from the United Kingdom: analysis of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, and antimicrobial resistance patterns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:853-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huebner, R. E., A. D. Wasas, and K. P. Klugman. 2000. Trends in antimicrobial resistance and serotype distribution of blood and cerebrospinal fluid isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in South Africa, 1991-1998. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 4:214-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs, M., H. Koornhof, R. Robins-Browne, C. Stevenson, Z. Vermaak, I. Freiman, G. Miller, M. Witcomb, M. Isaacson, J. Ward, and R. Austrian. 1978. Emergence of multiply resistant pneumococci. N. Engl. J. Med. 299:735-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan, S. L., and E. O. Mason. 1998. Management of infections due to antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:628-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan, S. L., E. O. Mason, W. J. Barson, T. Q. Tan, G. E. Schutze, H. S. Bradley, L. B. Givner, K. S. Kim, R. Yogev, and E. R. Wald. 2001. Outcome of invasive infections outside the central nervous system caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates nonsusceptible to ceftriaxone in children treated with beta-lactam antibiotics. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:392-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlowsky, J. A., M. E. Jones, D. C. Draghi, and D. F. Sahm. 2003. Clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with different susceptibilities to ceftriaxone and cefotaxime. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3155-3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klugman, K., H. Koornhof, and I. Friedland. 1992. Antibiotic resistance in pneumococcal meningitis. Lancet 340:437-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefevre, J. C., G. Faucon, A. M. Sicard, and A. M. Gasc. 1993. DNA fingerprinting of Streptococcus pneumoniae strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2724-2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maisnier-Patin, S., O. G. Berg, L. Liljas, and D. I. Andersson. 2002. Compensatory adaptation to the deleterious effect of antibiotic resistance in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 46:355-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDougal, L. K., J. K. Rasheed, J. W. Biddle, and F. C. Tenover. 1995. Identification of multiple clones of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2282-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGee, L., L. McDougal, J. Zhou, B. G. Spratt, F. C. Tenover, R. George, R. Hakenbeck, W. Hryniewicz, J. C. Lefevre, A. Tomasz, and K. P. Klugman. 2001. Nomenclature of major antimicrobial-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae defined by the pneumococcal molecular epidemiology network. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2565-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2003. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Thirteenth informational supplement, M100-S13. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 24.Nilsson, A. I., O. G. Berg, O. Aspevall, G. Kahlmeter, and D. I. Andersson. 2003. Biological costs and mechanisms of fosfomycin resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2850-2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pallares, R., O. Capdevila, J. Linares, I. Grau, H. Onaga, F. Tubau, M. H. Schulze, P. Hohl, and F. Gudiol. 2002. The effect of cephalosporin resistance on mortality in adult patients with nonmeningeal systemic pneumococcal infections. Am. J. Med. 113:120-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schrag, S. J., V. Perrot, and B. R. Levin. 1997. Adaptation to the fitness costs of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 264:1287-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simberkoff, M. S., M. Lukaszewski, A. Cross, M. Al-Ibrahim, A. L. Baltch, R. P. Smith, P. J. Geiseler, J. Nadler, and A. S. Richmond. 1986. Antibiotic-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae from clinical specimens: a cluster of serotype 19A organisms in Brooklyn, New York. J. Infect. Dis. 153:78-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith, A. M., and K. P. Klugman. 2000. Non-penicillin-binding protein mediated high-evel penicillin and cephalosporin resistance in a Hungarian clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spika, J. S., R. R. Facklam, B. D. Plikaytis, M. J. Oxtoby, and the Pneumococcal Surveillance Working Group. 1991. Antimicrobial resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States, 1979-1987. J Infect. Dis. 163:1273-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turrett, G. S., S. Blum, B. A. Fazal, J. E. Justman, and E. E. Telzak. 1999. Penicillin resistance and other predictors of mortality in pneumococcal bacteremia in a population with high HIV seroprevalence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:321-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitney, C., M. Farley, J. Hadler, L. Harrison, C. Lexau, A. Reingold, L. Lefkowitz, P. Cieslak, M. Cetron, E. Zell, J. Jorgensen, and A. Schuchat. 2000. Increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 343:1917-1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]