Abstract

A detailed pharmacokinetic analysis was performed with 47 children from Papua New Guinea with uncomplicated falciparum or vivax malaria treated with artesunate (ARTS) suppositories (Rectocaps) given in two doses of approximately 13 mg/kg of body weight 12 h apart. Following an intensive sampling protocol, samples were assayed for ARTS and its primary active metabolite, dihydroartemisinin (DHA), by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. A population pharmacokinetic model was developed to describe the data. Following administration of the first dose, the mean maximal concentrations of ARTS and DHA were 1,085 nmol/liter at 0.9 h and 2,525 nmol/liter at 2.3 h, respectively. The absorption half-life for ARTS was 2.3 h, and the conversion half-life (ARTS to DHA) was 0.27 h, while the elimination half-life of DHA was 0.71 h. The mean common volumes of distribution for ARTS and DHA relative to bioavailability were 42.8 and 2.04 liters/kg, respectively, and the mean clearance values relative to bioavailability were 6 and 2.2 liters/h/kg for ARTS and DHA, respectively. Substantial interpatient variability was observed, and the bioavailability of the second dose relative to that of the first was estimated to be 0.72. The covariates age, sex, and α-thalassemia genotype were not influential in the pharmacokinetic model development; but the inclusion of weight as a covariate significantly improved the performance of the model. An ARTS suppositories dose of 10 of 20 mg/kg is appropriate for use in children with uncomplicated malaria.

The artemisinin derivatives are potent antimalarial drugs (17, 30, 31). Depending on the derivative, there are formulations that can be given by mouth, intravenous (i.v.) or intramuscular injection, or suppository (41). Artesunate (ARTS), the synthetic hemisuccinate ester of its active metabolite, dihydroartemisinin (DHA), has the most potential as an intrarectal preparation because its high water solubility should facilitate absorption across the rectal mucosa. ARTS suppositories have been identified as having great promise, especially for the treatment of pediatric malaria (40). They can be administered when a child cannot take oral therapy and/or when parenteral drug administration is not possible and have proved effective in adults (4, 28, 29) and children (13, 23, 25, 33) with uncomplicated malaria.

Although the therapeutic indices of the artemisinin derivatives appear to be high (16, 17, 30, 31), there are still concerns that the neurotoxicity found in animal studies (8, 27) may occur in humans, especially children (21). There is therefore a need for continued pharmacokinetic assessment of artemisinin formulations so that safe and effective regimens can be developed. Three published studies have reported pharmacokinetic data from studies with children with falciparum malaria treated rectally with ARTS, two from Africa (13, 25) and one from Thailand (34). In two of those studies (13, 33), only basic pharmacokinetic data were reported. A larger crossover study in which higher rectal and i.v. doses were used for the treatment of moderately severe falciparum malaria (25) generated absolute bioavailability data, but analysis of plasma DHA concentrations was possible only after the administration of a single dose. There is evidence that the pharmacokinetics of artemisinin derivatives change significantly with repeated dosing (3, 24, 32), but this has not been assessed in the case of rectal ARTS.

The burden of malaria is significant in many Melanesian populations, especially among children. Given the limited health care infrastructure, ARTS suppositories represent an attractive therapeutic option in countries such as Papua New Guinea (PNG). However, the applicability of dose regimens developed in studies with other racial groups is uncertain. In addition, hemoglobin variants that result in conditions such as α-thalassemia and that may alter the dispositions and efficacies of artemisinin drugs (10, 20, 22, 34, 38) have a high prevalence in some Melanesian populations (1). There have been no previous pharmacokinetic studies of rectal ARTS in patients with hemoglobinopathies.

In view of these considerations, we have investigated the pharmacokinetics of ARTS and DHA in PNG children who (i) had uncomplicated falciparum or vivax malaria, (ii) were from an area with a high prevalence of α-thalassemia, and (iii) received two doses of rectal ARTS 12 h apart.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Details of the patients recruited to the present study have been published previously, together with the results of clinical and parasitological measures of response to rectal ARTS (23). The study was conducted in Madang Province, an area on the north coast of PNG where Plasmodium falciparum is hyperendemic (9), between March and May 2001. Children aged 5 to 10 years with a history of fever and a blood film positive for either P. falciparum or P. vivax were eligible for recruitment, provided that they (i) had no features of severe malaria (39), (ii) had not taken antimalarial drugs in the previous 28 days, (iii) did not have clinical evidence of another infection as a cause of fever, and (iv) had no history of diarrhea. Informed consent was obtained from a parent prior to recruitment.

Clinical procedures.

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia and the Medical Research Advisory Committee of PNG. All children recruited into the study were admitted to the provincial hospital for at least 24 h. An initial clinical assessment was performed, and blood was taken for baseline tests, including full blood count and plasma glucose level determination. A skilled microscopist confirmed the diagnosis of malaria, and the parasite density was calculated from the number of asexual forms per 1,000 leukocytes and the whole-blood leukocyte count.

ARTS was given per rectum at a dose of 10 to 15 mg/kg of body weight with the closest whole suppository. A combination of between one and four 50- and 200-mg Plasmotrim Rectocaps suppositories (Mepha Ltd., Aesch-Basel, Switzerland) was used to make up the total dose for each child. Suppositories were kept at room temperature and were removed from their airtight foil packaging immediately before use. They were administered base first without lubricant, and the exact time of administration was recorded. A second ARTS dose of 10 to 15 mg/kg was administered per rectum 12 h after administration of the initial dose. If the child passed a suppository within 1 h of administration, a repeat dose was administered. If the suppository was passed after 1 h, the child was withdrawn from the study and given chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, in accordance with standard treatment recommendations in PNG.

Patients were assessed every 4 h by measurement of oral temperature, pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and plasma glucose level. Urine output and conscious state were also assessed, and a blood sample for preparation of a thick film was taken at these times. Children who developed signs of complicated malaria at any time were to be withdrawn from the study and given intramuscular quinine, as recommended for complicated malaria in PNG. Each child received a standard course of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and chloroquine at 24 h after administration of the first dose of ARTS and was subsequently discharged when he or she was aparasitemic and afebrile. Pharmacodynamic outcomes, including fever clearance time (FCT) and parasite clearance time (PCT), have been described in detail elsewhere (23).

A heparinized intravenous cannula was inserted into each child at the time of admission. A baseline sample of 3 ml of venous blood was taken; and further samples of 3 ml were drawn through the cannula at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 12 h after administration of the first dose and 2, 4, 8, and 12 h after administration of the second dose. Blood was collected and placed into fluoride-oxalate tubes that were then kept on ice for <30 min prior to centrifugation, and the separated plasma was stored and transported at <−20°C until it was analyzed.

Drug assays.

ARTS, DHA, and artemisinin (QHS) reference standards were a gift from Col Brian Schuster (Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Washington, D.C.). High-performance liquid chromatography-grade methanol and acetonitrile and analytical reagent-grade lithium hydroxide were obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Acetic acid, butylchloride, and ethyl acetate were obtained from BDH Laboratory Supplies (Poole, United Kingdom). Deionized water was used in all buffers. Blood for the generation of standard curves was obtained from healthy volunteers and placed into fluoride-oxalate tubes. The separated plasma was stored at −80°C until it was assayed. Standard curves were prepared by spiking 1-ml aliquots of plasma with ARTS (130 to 2,080 nmol/liter), DHA (176 to 2,820 nmol/liter), and artemisinin (1 mg, as an internal standard) in methanol (0.1 ml). The plasma was then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 1 min to precipitate the proteins, and the supernatant was subjected to solid-phase extraction, as described previously (6). The stability of ARTS and DHA in plasma during storage for up to 12 months has been demonstrated previously.

ARTS and DHA were analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) with an Agilent 1100 Series LC system (Aglient Technologies, Forest Hill, New South Wales, Australia). Analytes were resolved on a Zorbax SB-C8 column (3.5 μm; 2.1 mm [inner diameter] by 100 mm; Aglient Technologies) fitted with an Eclipse XDB-C8 guard column (5 mm; 2.1 mm [inner diameter] by 12.5 mm; Aglient Technologies). The mobile phase of 55% 0.01 M LiOH · H2O (adjusted to pH 4.8 with acetic acid), and 45% acetonitrile was pumped at 200 μl/min. Aliquots of the plasma extracts (8 μl) were injected onto the column, and eluting peaks were detected sequentially by detection of UV absorbance (210 nm) and by use of an MSD trap (1100 series; Agilent).

The mass spectrometer was operated by using electrospray ionization in the positive ion mode. ARTS and DHA both produced ion fragmentation patterns with one major ion at 245 m/z. On a molar basis, the intensity of the ion for DHA was approximately threefold that for ARTS. Artemisinin had major ions at 261 and 289 m/z, both with responses that were approximately 0.5 times those for DHA. Hence, analytes were quantified by single-ion monitoring in two separate windows, one (0 to 7 min) at 245 m/z to monitor ARTS and DHA and the other (7 to 13 min) at 261 m/z to monitor artemisinin. Nitrogen was used as the nebulizer gas at a pressure of 40 lb/in2 and a vaporizer temperature of 325°C. The compound stability was set at 50%, and the trap drive level was set at 80%. Under these conditions, the approximate retention times for ARTS, α-DHA, β-DHA, and QHS were 3, 4, 5.4, and 7.9 min, respectively. The total analysis time for each run was 13 min.

Stock solutions of ARTS, DHA and QHS were prepared at 1 mg/ml in methanol and stored at −20°C. A 100-fold dilution of each stock solution (10 μg/ml) was prepared as a working standard on each day. A four-point calibration curve (ARTS and DHA) was prepared for each sample batch (see above). ARTS and DHA were quantified by using the ratio of the peak area of the analyte to that of the internal standard. For ARTS, intraday relative standard deviations (RSDs) were 16.6, 11.2, and 3.3% at 130, 1,040, and 2,080 nmol/liter, respectively (n = 5), while interday RSDs were 12.5, 14.3, 14.1, and 7.2% at 260, 520, 1,040, and 2,080 nmol/liter, respectively (n = 5 to 7). For DHA, intraday RSDs were 11.8, 9.9, 7.5, 9.9, and 2.5% at 70, 176, 704, 1,408, and 2,816 nmol/liter, respectively (n = 5), while interday RSDs were 13.5, 8.7, 6.6, and 6.3% at 176, 704, 1,408, and 2,816 nmol/liter, respectively (n = 4 to 7). The limits of quantitation (RSD, ≤20%) and the limits of detection (three times the baseline) for the assay were 80 and 50 nmol/liter, respectively, for ARTS and 50 and 10 nmol/liter, respectively, for α-DHA.

α-Thalassemia genotyping.

Whole blood was collected in tubes with EDTA and assayed for the six common deletional variants of the two α-thalassemia genes by a single-tube multiplex PCR by the method described by Chong et al. (11). On the basis of the results of the assay, each patient was classified as normal (homozygous wild type), heterozygous (one abnormal gene), homozygous (two copies of a single gene deletion type), or dual heterozygous (one copy each of two different gene deletion types).

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analyses.

Plasma ARTS and DHA concentrations were analyzed by population pharmacokinetic analysis with the NONMEM program, version V (7). The results obtained with the NONMEM program were postprocessed and visualized by using PDx-Pop software (version 1.1; Globomax, Hanover, Md.). The data for DHA and four datum points for ARTS between the limits of detection and quantitation were allowed to remain in the analysis to assist with model stability. For covariate inclusion in the final population pharmacokinetic model, an increase of at least 6.63 points (P < 0.01) in the value of the approximate first-order objective function, as reported by the NONMEM program, was required.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics and clinical course.

A total of 48 children were recruited. One patient was excluded due to witnessed passage of the suppository 2 h after the commencement of treatment. Of the remaining 47 patients, 42 had falciparum malaria and 5 had vivax malaria. Their baseline characteristics, including α-thalassemia genotype, are summarized in Table 1. The treatment was well tolerated, and no side effects attributable to the suppositories were reported. As reported previously (23), only one child had persistent parasitemia and only one had not defervesced by 24 h. These two children received intramuscular quinine and recovered uneventfully.

TABLE 1.

Details of patients at the time of admission to the study and outcome variablesa

| Characteristic | P. falciparum | P. vivax |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 42 | 5 |

| Age (yr) | 7.4 ± 1.6 | 6 (5-6) |

| Sex (% males) | 60 | 60 |

| Body wt (kg) | 20.7 ± 4.3 | 17.5 (15-23) |

| Oral temp (°C) | 38.1 ± 0.9 | 38.2 (37.6-40.8) |

| Splenomegaly (% of patients) | 74 | 40 |

| Venous hematocrit (%) | 34.1 ± 5.1 | 33.3 ± 5.9 |

| Parasite density (no./μl) | 36,900 (130-326,000) | 7,480 (630-13,300) |

| Plasma glucose concn (mmol/liter) | 6.4 ± 1.3 | 5.2 ± 1.2 |

| ARTS dose (mg/kg) | 12.7 ± 0.9 | 12.8 ± 0.9 |

| α-Thalassemia genotype (no. [%] of patients) | ||

| Wild type (two normal genes) | 9 (22) | 1 (20) |

| Heterozygous (one gene deletion) | 14 (34) | 1 (20) |

| Homozygous (two gene deletions) | 16 (49) | 3 (60) |

| Dual heterozygous (two different gene deletions) | 2 (5) | 0 |

Unless specified otherwise, the data are means ± standard deviations or medians (ranges).

Pharmacokinetic analysis.

Despite the high sensitivities of the assays, particularly of the assay for DHA, the levels of ARTS and DHA following administration of one of the two doses were undetectable in seven patients: four after the first dose and three after the second dose (including the child with persistent parasitemia at 24 h). All seven patients showed good absorption of the other dose. In the four patients with undetectable drug levels after the first dose, the mean time to a 90% reduction in the level of parasitemia from the baseline level (PCT90) was 20.0 h, compared with 9.5 h for the 40 patients who had measurable drug levels after both doses (P = 0.001). Given the difficulties of close monitoring of the patients, it was suspected that these seven children extruded the suppository after administration without the knowledge of the investigators, and pharmacokinetic data for these seven patients were excluded from the analysis. ARTS concentrations were not available for 27 data sets due to difficulties with the LC-MS instrument setup and sensitivity and the fact that insufficient sample sizes were available to repeat these analyses. Overall, 43 first-dose and 44 second-dose DHA data sets and 19 first-dose and 19 second-dose ARTS data sets were available for pharmacokinetic analysis.

Selection of a three-compartment structural model was guided by previous studies of the metabolic disposition (19, 26) and pharmacokinetics (5, 6, 12, 18) of ARTS and DHA in adults. The model comprises compartment 1 (the rectal absorption site), compartment 2 (the ARTS data set), compartment 3 (the DHA data set), and three rate constants, k12, k23, and k30. In keeping with knowledge of the metabolism of ARTS and DHA, conversion of ARTS to DHA (rate constant = k23) was assumed to be quantitative (26), and irreversible elimination of DHA was assumed to occur from compartment 3 (rate constant = k30) (19). Since each patient received two equal doses of ARTS 12 h apart, we incorporated a relative bioavailability term into the model, which was set at 100% for the first administration and which was estimated as a separate parameter for the second dose (FRAC). The dose (in nanomoles) was entered into the model for each patient. In addition, since the dose was administered rectally, model-derived estimates of both clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (V) were estimated relative to bioavailability (F). A total of 78 datum points were available for ARTS and 291 were available for DHA. These included 10 datum points for DHA and 4 datum points for ARTS between the limits of detection and quantitation.

The initial values for the fit were obtained by performing a naïve pooled estimate of all data against the model by using the SAAM II program (SAAM II Program and User Guide, version 1.2, 2000; SAAM Institute Inc., University of Washington, Seattle) with average values for the dose and the time of the second dose. The steps in model development were as follows. Base model 1 (parameters V1/F (ARTS), V2/F (DHA), and FRAC were assumed to be fixed effects in the population) consistently underestimated the predicted drug concentrations and, despite alterations such as the inclusion of a lag time, failed to adequately represent the data on the basis of standard criteria (objective function = 5,972). Base model 2 (parameters V1/F, V2/F with random effects in the population, and FRAC, which was assumed to be a fixed effect in the population) marginally improved the overall objective function (5,790.6), but there was still a problem with model identifiability, particularly at higher concentrations, and estimates of V2/F and k30 were poorly defined. Because of the latter, V1/F and V2/F were set equal in model 3 (proportional measurement error and constant coefficient of variation for between-subject variability); and this resulted in improved model identifiability, more robust parameter estimates, and a marginal improvement in the objective function (5,789.6).

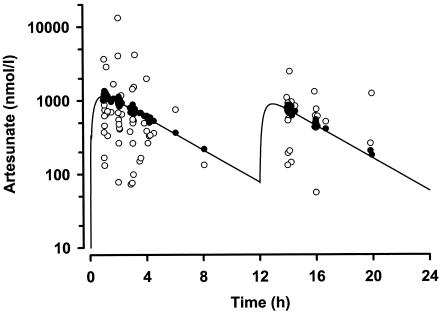

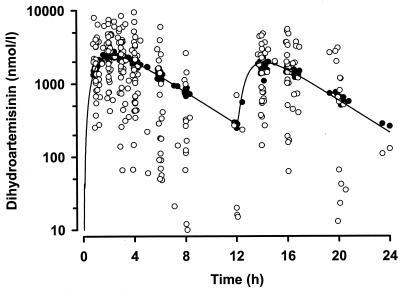

In the final model, we investigated age, sex, α-thalassemia genotype, and weight as covariates. Only weight was influential, and its inclusion in the volume term [as (V/F · weight)/median weight] resulted in a substantial improvement in the objective function (5,721.2) and overall model performance. The possibility that a “flip-flop” phenomenon occurred between k12 and k23 was considered during model development, but the order of magnitude of the value of k23 was consistent with previously reported values (5, 6, 12). The mean parameter estimates for the final model and the individual and residual variability factors for the model are summarized in Table 2. Plots of model-predicted and observed ARTS and DHA concentration-time data are shown in Fig. 1 and 2, respectively. For both drugs, the weighted residual values for the model plotted versus subject number were evenly and tightly distributed about zero (data not shown). Table 3 summarizes the individual pharmacokinetic parameters derived from post hoc Bayesian predictions and/or calculated from these by using standard pharmacokinetic equations (15). Mean maximum concentrations in serum (Cmax) and times to Cmax (Tmax) for ARTS and DHA were simulated by use of the kinetic data from Table 3. For ARTS a Cmax of 1,085 nmol/liter occurred at 0.9 h, and for DHA Cmax was 2,525 nmol/liter at 2.3 h. Consistent with the slow absorption of rectal ARTS, the mean ARTS-to-DHA conversion half-life (t1/2; 16 min) was some five times greater than that in previous studies of oral or i.v. ARTS (2 to 4 min) (5, 6, 12). Nevertheless, the elimination t1/2 for DHA (43 min) was in the range of those found in previous studies of oral or i.v. ARTS (39 to 64 min) (5, 6, 12). Data for four patients with P. vivax malaria were initially analyzed separately, but no statistically significant differences in any derived pharmacokinetic parameters from those for patients with P. falciparum malaria were seen, and the data were included together in the pooled analysis.

TABLE 2.

Parameters and performance descriptors for the final pharmacokinetic model

| Parameter | Final estimate | % RSEa | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | CVb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theta | |||||

| 1 (k12) | 0.253 | 18.1 | 0.163 | 0.343 | |

| 2 (k23) | 2.8 | 22.8 | 1.55 | 4.05 | |

| 3 (k30) | 1.03 | 19.4 | 0.638 | 1.42 | |

| 4 (V/F) | 41.8 | 20.4 | 25.2 | 58.4 | |

| 5 (FRAC) | 0.72 | 9.68 | 0.583 | 0.857 | |

| Omega (CV2)c | |||||

| k12 | 0.412 | 31.3 | 0.158 | 0.665 | 64.2 |

| k23 | 0.303 | 126.0 | −0.448 | 1.05d | 55.0 |

| k30 | 0.162 | 37.3 | 0.0434 | 0.281 | 40.2 |

| FRACe | 0.179 | 61.2 | −0.0338 | 0.374d | 41.2 |

| Sigma (CV2)e | |||||

| ARTS | 3.02 | 53.3 | −0.136 | 6.18d | 174 |

| DHA | 0.625 | 15.7 | 0.433 | 0.817 | 79.1 |

RSE, relative standard error [(100 * SE)/estimate].

CV, population coefficient of variation [(standard deviation·100)/mean value].

Omega, maximum-likelihood estimates of variances of between-subject variability. Note that V/F has no random effect since its variation is modeled only by the covariate weight.

The 95% confidence interval includes zero.

Sigma, maximum-likelihood estimates of variances of random unexplained variability.

FIG. 1.

Plot of population model prediction (•) and actual measurements (○) of the ARTS concentration against time (semilogarithmic scale). The solid line shows the plasma ARTS concentration simulated by using the mean parameters for the model, a 12.75-mg/kg dose at zero time and 72% of that dose at 12 h.

FIG. 2.

Plot of population model prediction (•) and actual measurements (○) of the DHA concentration against time (semilogarithmic scale). The solid line shows the plasma DHA concentration simulated by using the mean parameters for the model, a 12.75-mg/kg dose at zero time and 72% of that dose at 12 h.

TABLE 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for the model

| Drug and parameter | Value (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|

| ARTS | |

| F (dose 2) | 0.72 ± 0.21 |

| V1/F (liters) | 42.9 ± 8.1 |

| k12 (/h) | 0.27 ± 0.18 |

| t1/2, absorption (h) | 2.3 ± 1.0 |

| k23 (/h) | 2.81 ± 0.65 |

| t1/2, conversion (h) | 0.27 ± 0.13 |

| CL/F, conversion (liters/h) | 121.2 ± 35.4 |

| DHA | |

| V2/F (liters) | 42.9 ± 8.1 |

| k30 (/h) | 1.06 ± 0.28 |

| t1/2, elimination (h) | 0.71 ± 0.22 |

| CL/F, elimination (liters/h) | 44.9 ± 13.0 |

α-Thalassemia status.

The α-thalassemia genotypes of 46 patients were determined and were wild type (two normal genes) for 22% of the patients, heterozygous for one abnormal gene for 33%, and either homozygous or dual heterozygous for 46%. Comparison of pharmacodynamic outcomes (FCT, PCT, PCT50, and PCT90) for each of these three groups by analysis of variance revealed no significant between-group variability.

DISCUSSION

The present study has provided novel data relating to the population pharmacokinetics of both ARTS and DHA in Melanesian children with a high prevalence of α-thalassemia mutations and from whom blood samples were obtained after both doses of rectal ARTS had been given 12 h apart. In one of every seven children, there was evidence that one of the doses was expelled soon after administration, but this did not result in any cases of early treatment failure (23). For those for whom data for the 24-h sampling period were valid, the bioavailability of DHA was an average of 28% lower after the second dose than after the first dose. We found that α-thalassemia had no influence on the pharmacokinetic properties of ARTS and DHA or on PCT or FCT.

Our derived pharmacokinetic parameters are difficult to compare with those from previous studies with children with falciparum malaria performed by Halpaap et al. (13) and Sabchareon et al. (33). The former group of investigators used a dose of rectal ARTS of only 1.2 to 2.2 mg/kg, given at 0 and 4 h, and determined Cmax and Tmax after the first dose (13). The mean Cmaxs of ARTS and DHA in plasma were 317 and 634 nmol/liter, respectively, and they occurred close to 1 h after drug administration. Given the proportionately lower dose used, these data are consistent with those observed in the present study. Of 12 subjects, 1 had very low concentrations after the first dose, implying that, as in the present study, the suppository had not been retained. In the Thai study (33), pharmacokinetic analysis was performed with an undefined subset of 19 of 52 children who received 10 or 19 mg of rectal ARTS per kg once a day for 3 days; and Cmax, elimination t1/2, and the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) from 0 to 12 h for DHA were derived. The mean Cmax, presumably after the first dose, was 2,382 nmol/liter, and the mean apparent elimination t1/2 was 0.7 h. These values are similar to those observed in our children from PNG and, consistent with the findings of Halpap et al. (13), show that peak plasma DHA concentrations are achieved promptly after drug administration. Krishna et al. (25) used doses of approximately 10 or 20 mg/kg in Ghanaian children with moderately severe malaria. The mean Cmaxs of DHA were 2,400 and 3,100 μmol/liter, respectively, in these two groups, with Tmax values just under 2 h in each group. As with the first two studies (13, 33), these results are in accord with those for our PNG children. Krishna et al. (25) also reported an inverse relationship between dose and bioavailability.

Krishna et al. (25) incorporated a lag time (means, 0.6 and 0.4 h for the low- and high-dose groups, respectively) into their one-compartment model, and the mean DHA absorption t1/2 estimates for their patients were 0.7 and 1.1 h, respectively. These parameters describe the same processes as our absorption t1/2 for ARTS (mean, 2.3 h) and t1/2 for ARTS conversion to DHA (mean, 0.3 h), with the result being that the mean Tmaxs for DHA in our patients (2.3 h) and in theirs (1.8 h) were similar. Values from our population model for V/F and CL/F (2.15 liters/kg and 2.25 liters/h/kg, respectively) were within the range of values for these two variables from the 26 subjects studied by Krishna et al. (25) (1.1 to 14.4 liters/kg and 1.0 to 22.3 liters/h/kg), although the values were toward the lower limit in each case. This most likely reflects the fact that our patients were older (mean ages, 7 and 4.1 years, respectively).

The similarity between the disposition of DHA after rectal administration of ARTS in our children from PNG and those in the study with Ghanaian children extends to the high interpatient variability in Cmax and AUC and, therefore, in F. The relative F of DHA after rectal ARTS administration compared with that after i.v. ARTS administration ranged from 6 to 131% in the study by Krishna et al. (25), and it is likely that the same magnitude of variation would be found for the patients in the present study. This has implications for treatment. There is evidence that the therapeutic indices of the artemisinin derivatives are large (16, 17, 30, 31), and so high rectal doses of ARTS (e.g., 20 mg/kg) should ensure therapeutic concentrations in plasma without the induction of unacceptable side effects in children with malaria.

Relative to the values of F after administration of the first dose of ARTS in the patients in the present study (F = 1.0 or 100%), there was a significant decrease in F after administration of the second rectal dose in our children (mean, 0.73), and only 3 of the 41 patient data sets (7.3%) had a second-dose F >1.0 (F values, 1.08, 1.23, and 1.52, respectively). Although the data were not presented, Krishna et al. (25) stated that there were no differences in pharmacokinetic parameters for high-dose DHA suppositories given 12 h apart. However, the same investigators found a borderline (P = 0.06) difference between DHA AUC values for i.v. doses at 0 and 12 h (25). In addition, a variety of studies have suggested a time-dependent reduction in the F values of artemisinin derivatives during treatment (3, 14, 32, 35), including during the first few days of ARTS therapy (24).

The reasons for the change in F between the first and second doses are unclear but may relate to changes in physiological factors. In the present study, a relatively high core body temperature at the time of the first dose may have led to greater rectal blood flow and better absorption of the drug compared to that after the second dose. Given the less frequent sampling schedule that we used following the second dose of ARTS, it was not practicable to analyze the pharmacokinetics of both doses separately. However, the induction of the metabolic clearance of ARTS or DHA is less likely in our view because their metabolic pathways (hydrolysis [26] and glucuronidation [19], respectively) are unlikely to change acutely. Nevertheless, there is clear evidence for the induction of ARTS metabolism during repeated administration of an oral or rectal dose (18, 42), largely as a result of CYP2B6 induction (36).

The high prevalence of α-thalassemia in the region of PNG where the children in the present study live was confirmed, with 78% of our sample having at least one abnormal α-thalassemia gene and 46% being either homozygous or dual heterozygous for abnormal genes. In non-malaria parasite-infected volunteers with thalassemia, Ittarat et al. (20) found that the mean AUC of ARTS plus DHA measured by bioassay after i.v. administration of ARTS was 9-fold higher and that the value of V at steady state was 15-fold lower than the values measured in healthy subjects. These findings were attributed to the accumulation of ARTS derivatives in thalassemic erythrocytes (22) or perhaps to differences in ARTS metabolism in thalassemic subjects. During the model-building process, we attempted to improve the description by using the α-thalassemia genotype as a covariate of V/F. However, this did not alter V/F significantly or decrease its variability, and between-subject variability was also unchanged. There may be other factors relating to malaria infection itself that explain the differences between our results and those of Ittarat et al. (20), but the scope of their investigation was beyond that of the present study.

In vitro studies have demonstrated markedly increased 50% inhibitory concentrations of artemisinin drugs in parasite cultures with thalassemic red blood cells (10, 22, 34, 37, 38). The determinants of reduced parasite susceptibility to artemisinin drugs in thalassemic cells remain unclear but may relate to competitive uptake and inactivation of drug by thalassemic host cell components, the abnormal hemoglobin itself (38), erythrocyte membrane-bound heme (37), or alterations in oxidative stress within parasitized thalassemic erythrocytes (34). Whether these findings have relevance in vivo is unclear, as we found no influence of thalassemia mutations on PCT or FCT. The present findings, coupled with the lack of observed toxicity and excellent clinical efficacy in this population, are reassuring for the future use of artemisinin derivatives in Melanesian and other populations with a high prevalence of this common hemoglobin variant.

Analysis of patients treated with oral ARTS suggests that a dose-parasite clearance response relationship may exist for DHA at concentrations of up to 1,400 nmol/liter (2). Present manufacturer and World Health Organization guidelines recommend a rectal dose of 5 mg/kg (41). We believe that an initial regimen of two 10- to 20-mg/kg doses 12 h apart is justified on the basis of the pharmacokinetic and dynamic data from the present and other studies, present knowledge of the dose-response relationships of artemisinin drugs, the wide variability in the values of F for ARTS suppositories, and the fact that the toxic threshold is very unlikely to be exceeded. However, larger-scale safety and cost-effectiveness studies are warranted before high-dose rectal ARTS can be recommended widely.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the Rotary Club of Scarborough, WA, Australia, and by Mepha Ltd. This work has been partially supported by NIH/NIBIB grant P41 EB-001975.

We are grateful to Kevin Croft and Lincoln Morton for consultations regarding the LC-MS analysis; the staff of Modilon General Hospital, Madang, for assistance with running the clinical study; the staff of the PNG IMR field station in Madang for technical assistance; and Michael G. Dodds for assistance with the population pharmacokinetic analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen, S. J., A. O'Donnell, N. D. E. Alexander, M. P. Alpers, T. E. A. Peto, J. B. Clegg, and D. J. Weatherall. 1997. α+-Thalassemia protects children against disease caused by other infections as well as malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:14736-14741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus, B. J., I. Thaiaporn, K. Chanthapadith, Y. Suputtamongkol, and N. J. White. 2002. Oral artesunate dose-response relationship in acute falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:778-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashton, M., D. S. Nguyen, V. H. Nguyen, T. Gordi, N. H. Trinh, X. H. Dinh, T. N. Nguyen, and D. C. Le. 1998. Artemisinin kinetics and dynamics during oral and rectal treatment of uncomplicated malaria. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 63:482-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awad, M. I., A. M. Y. Alkadru, R. H. Behrens, O. Z. Baraka, and I. B. Eltayeb. 2003. Descriptive study on the efficacy and safety of artesunate suppository in combination with other antimalarials in the treatment of severe malaria in Sudan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 63:153-158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batty, K. T., A. T. Le, K. F. Ilett, P. T. Nguyen, S. M. Powell, C. H. Nguyen, X. M. Truong, V. C. Vuong, V. T. Huynh, Q. B. Tran, V. M. Nguyen, and T. M. Davis. 1998. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of artesunate for vivax malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 59:823-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batty, K. T., L. T. Thu, T. M. Davis, K. F. Ilett, T. X. Mai, N. C. Hung, N. P. Tien, S. M. Powell, H. V. Thien, T. Q. Binh, and N. V. Kim. 1998. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of intravenous vs oral artesunate in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 45:123-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beal, S. L., and L. B. Sheiner. 1992. NONMEM user guide. NONMEM Project Group, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco.

- 8.Brewer, T. G., J. O. Peggins, S. J. Grate, J. M. Petras, B. S. Levine, P. J. Weina, H. Searengen, M. H. Heffer, and B. G. Schuster. 1994. Neurotoxicity in animals due to arteether and artemether. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 88:33-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cattani, J. A., J. L. Tulloch, H. Vrbova, D. Jolley, F. D. Gibson, J. S. Moir, P. F. Heywood, M. P. Alpers, A. Stevenson, and R. Clancy. 1986. The epidemiology of malaria in a population surrounding Madang, Papua New Guinea. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 35:3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charoenteeraboon, J., S. Kamchonwongpaisan, P. Wilairat, P. Vattanaviboon, and Y. Yuthavong. 2000. Inactivation of artemisinin by thalassemic erythrocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 59:1337-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong, S. S., C. D. Boehm, D. R. Higgs, and G. R. Cutting. 2000. Single-tube multiplex-PCR screen for common deletional determinants of alpha-thalassemia. Blood 95:360-362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis, T. M., H. L. Phuong, K. F. Ilett, N. C. Hung, K. T. Batty, V. D. Phuong, S. M. Powell, H. V. Thien, and T. Q. Binh. 2001. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous artesunate in severe falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:181-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halpaap, B., M. Ndjave, M. Paris, A. Benakis, and P. G. Kremsner. 1998. Plasma levels of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin in children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Gabon after administration of 50-milligram artesunate suppositories. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 58:365-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassan Alin, M., M. Ashton, C. M. Kihamia, G. J. Mtey, and A. Bjorkman. 1996. Multiple dose pharmacokinetics of oral artemisinin and comparison of its efficacy with that of oral artesunate in falciparum malaria patients. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 90:61-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinzel, G., and P. Tanswell. 1993. Compartmental analysis methods manual, p. 5-140. In G. Heinzel, R. Woloszcak, and P. Thomann (ed.), Topfit 2.0 pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis system for the PC. Gustav Fischer, Stuttgart, Germany.

- 16.Hien, T. T., G. D. H. Turner, N. T. H. Mai, N. H. Phu, D. Bethell, W. F. Blakemore, J. B. Cavanagh, A. Dayan, I. Medana, R. O. Weller, N. P. J. Day, and N. J. White. 2003. Neuropathological assessment of artemether-treated severe malaria. Lancet 362:395-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hien, T. T., and N. J. White. 1993. Qinghaosu. Lancet 341:603-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilett, K. F., K. T. Batty, S. M. Powell, T. Q. Binh, T. A. Thu le, H. L. Phuong, N. C. Hung, and T. M. Davis. 2002. The pharmacokinetic properties of intramuscular artesunate and rectal dihydroartemisinin in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 53:23-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilett, K. F., B. T. Ethell, J. L. Maggs, T. M. Davis, K. T. Batty, B. Burchell, T. Q. Binh, T. A. Thu le, N. C. Hung, M. Pirmohamed, and B. K. Park. 2002. Glucuronidation of dihydroartemisinin in vivo and by human liver microsomes and expressed UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug Metab. Dispos. 30:1005-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ittarat, W., S. Looareesuwan, P. Pootrakul, P. Sumpunsirikul, P. Vattanavibool, and S. R. Meshnick. 1998. Effects of alpha-thalassemia on pharmacokinetics of the antimalarial agent artesunate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2332-2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johann-Liang, R., and R. Albrecht. 2003. Safety evaluations of drugs containing artemisinin derivatives for the treatment of malaria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:1626-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamchonwongpaisan, S., G. Chandrangam, M. A. Avery, and Y. Yuthavong. 1994. Resistance to artemisinin of malaria parasites (Plasmodium falciparum) infecting alpha-thalassemic erythrocytes in vitro. Competition in drug accumulation with uninfected erythrocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 93:467-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karunajeewa, H. A., A. Kemiki, M. P. Alpers, K. Lorry, K. T. Batty, K. F. Ilett, and T. M. Davis. 2003. Safety and therapeutic efficacy of artesunate suppositories for treatment of malaria in children in Papua New Guinea. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22:251-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khanh, N. X., P. J. De Vries, L. D. Ha, C. J. van Boxtel, R. Koopmans, and P. A. Kager. 1999. Declining concentrations of dihydroartemisinin in plasma during 5-day oral treatment with artesunate for falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:690-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishna, S., T. Planche, T. Agbenyega, C. Woodrow, D. Agranoff, G. Bedu-Addo, A. K. Owusu-Ofori, J. A. Appiah, S. Ramanathan, S. M. Mansor, and V. Navaratnam. 2001. Bioavailability and preliminary clinical efficacy of intrarectal artesunate in Ghanaian children with moderate malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:509-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee, I. S., and C. D. Hufford. 1990. Metabolism of antimalarial sesquiterpene lactones. Pharmacol. Ther. 48:345-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Q. G., S. R. Mog, Y. Z. Si, D. E. Kyle, M. Gettayacamin, and M. K. Milhous. 2002. Neurotoxicity and efficacy of arteether related to its exposure times and exposure levels in rodents. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66:516-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Looareesuwan, S., C. Viravan, S. Vanijanonta, P. Wilairatana, P. Pitisuttithum, and M. Andrial. 1996. Comparative clinical trial of artesunate followed by mefloquine in the treatment of acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria: two- and three-day regimens. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 54:210-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Looareesuwan, S., P. Wilairatana, S. Vanijanonta, C. Viravan, and M. Andrial. 1995. Efficacy and tolerability of a sequential, artesunate suppository plus mefloquine, treatment of severe falciparum malaria. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 89:469-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McIntosh, H. M., and P. Olliaro. 2000. Artemisinin derivatives for treating complicated malaria (Cochrane review). In The Cochrane library, issue 2. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 31.McIntosh, H. M, and P. Olliaro. 2000. Artemisinin derivatives for treating uncomplicated malaria (Cochrane review). In The Cochrane library, issue 2. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Newton, P., Y. Suputtamongkol, P. Teja-Isavadharm, S. Pukrittayakamee, V. Navaratnam, I. Bates, and N. White. 2000. Antimalarial bioavailability and disposition of artesunate in acute falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:972-977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabchareon, A., P. Attanath, P. Chanthavanich, P. Phanuaksook, V. Prarinyanupharb, Y. Poonpanich, D. Mookmanee, P. Teja-Isavadharm, D. G. Heppner, T. G. Brewer, and T. Chongsuphajaisiddhi. 1998. Comparative clinical trial of artesunate suppositories and oral artesunate in combination with mefloquine in the treatment of children with acute falciparum malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 58:11-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senok, A. C., E. A. Nelson, K. Li, and S. J. Oppenheimer. 1997. Thalassaemia trait, red blood cell age and oxidant stress: effects on Plasmodium falciparum growth and sensitivity to artemisinin. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91:585-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silamut, K., P. N. Newton, P. Teja-Isavadharm, Y. Suputtamongkol, D. Siriyanonda, M. Rasameesoraj, S. Pukrittayakamee, and N. J. White. 2003. Artemether bioavailability after oral or intramuscular administration in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:3795-3798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Svensson, U. S., M. Maki-Jouppila, K. J. Hoffman, and M. Ashton. 2003. Characterisation of the human liver in vitro metabolic pattern of artemisinin and auto-induction in the rat by use of nonlinear mixed effects modelling. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 24:71-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vattanaviboon, P., N. Sirianaratkul, J. Ketpriune, P. Wilairat, and Y. Yuthavong. 2002. Membrane heme as a host factor in reducing effectiveness of dihydroartemisinin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 64:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vattanaviboon, P., P. Wilairat, and Y. Yuthavong. 1998. Binding of dihydroartemisinin to hemoglobin H: role in drug accumulation and host-induced antimalarial ineffectiveness of alpha-thalassemic erythrocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 53:492-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. 2000. Severe falciparum malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 94(Suppl. 1):1-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. 15th Programme Report. Progress 1999-2000. Report TDR/GEN/01.5. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 41.World Health Organization. 1998. The use of artemisinin and its derivatives as anti-malarial drugs. Report WHO/MAL 1086. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 42.Zhang, S. Q., T. N. Hai, K. F. Ilett, D. X. Huong, T. M. Davis, and M. Ashton. 2001. Multiple dose study of interactions between artesunate and artemisinin in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 52:377-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]