Abstract

This paper describes an efficient colchicine-mediated technique for in vitro induction of octoploids in Pogostemon cablin and its confirmation by flow cytometry and chromosome numbers. The highest octoploid induction ratio was obtained by 0.05% colchicine treatment for 72 h. The chromosome number of octoploid seedlings was 2n = 8x = 128. Colchicine-induced tetraploids and octoploids planted in soil remained stable after 6 months. There were 31 lines of octoploid plants obtained. The leaf characteristics of P. cablin tetraploids and octoploids were compared. The larger leaves and stomata of transplants can be used to identify putative octoploids in P. cablin. Most octoploid lines exhibited higher patchoulic alcohol contents than the controls after 6 months of cultivation. Our results demonstrated that polyploidy induction can be beneficial in improving the medicinal value of P. cablin.

Keywords: Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth., colchicine, leaf characteristic, patchoulic alcohol, octoploidy

Introduction

Pogostemon cablin, of the genus Pogostemon, is a perennial herbal plant native to the Philippines. It is a traditional Chinese medicinal material commonly used in removing dampness, relieving summer-heat, exterior syndrome, stopping vomiting and stimulating the appetite. Recent studies showed that P. cablin has an in vitro antivirus effect (Kiyohara et al. 2012, Peng et al. 2011, Wang et al. 2011). During the Song dynasty, it was introduced from countries in Southeast Asia such as the Philippines and Indonesia to southern China. In China, P. cablin is generally propagated by cutting propagation because it does not bloom in southern China. This mode of reproduction leads to weaker resistance of progeny, and a decline in yield and quality. As the plant does not flower in southern China, and only reproduces asexually through stem cutting, it is very difficult to breed new cultivars using traditional methods. Consequently, it is not only necessary to develop new technologies to create germplasm resources, but also breed new cultivars with rapid growth and stable (and higher) content of patchouli oils.

In vitro multiplication of P. cablin has been performed using explants of stems (He et al. 2009), roots (Xiao et al. 2001), leaves (Du et al. 2002), callus (Zhang et al. 1994) and protoplasts (Mo et al. 2012). However, reports about in vitro polyploid induction in P. cablin are limited. Wu (Wu and Li 2013) induced tetraploids (2n = 4x = 56) by immersing shoot tips in 0.02% colchicine solution for 2 h before culture. This chromosome number differed from that found by Lavania (1984), Tyagi and Bahl (1990) and Chen et al. (2009) of 2n = 32 or 2n = 64. The basic chromosome number is x = 16 or 17 in Pogostemon (Cherian and Kuriachan 1993). From preliminary experiment results, we agree with the latter opinion that 2n = 2x = 32 or 2n = 4x = 64, and 2n = 4x = 64 is predominant in China (Xiong et al. 2013).

Polyploid cells contain more than two complete sets of chromosomes and are heritable. Polyploidy is estimated to have an occurrence rate in the range of 30–70% in plants (Wolfe 2001). Induction of polyploid plants has been of considerable interest for researchers (Cheng and Korban 2011). Characteristics such as larger leaves, stems, roots and flowers in polyploid compared to diploid plants can often be obtained (Watrous and Wimber 1988, Wimber et al. 1987). Thus, polyploid plants may have increased biomass and yield.

In vitro chromosome doubling can be induced by several antimitotic agents (Dhooghe et al. 2011), such as colchicine in Lagerstroemia indica (Zhang et al. 2010) and Paulownia tomentosa (Tang et al. 2010); oryzalin in Dendrobium, Epidendrum, Odontioda and Phalaenopsis orchids (Miguel and Leonhardt 2011); and trifluralin in Ranunculus (Dhooghe et al. 2009). There have been a number of reports of artificial tetraploid medicinal plants—such as Artemisia annua (Wallaart et al. 1999), Dioscorea zingiberensis (Huang et al. 2008), Papaver somniferum (Mishra et al. 2010) and Scutellaria baicalensis (Gao et al. 2002)—with increased biomass or higher content of phytochemicals.

To develop superior varieties of P. cablin, we report here a method for generating polyploid plants using colchicine. Octaploid lines of P. cablin were obtained and identified by flow cytometry, root-tip chromosome determination and stomatal observations.

Material and Methods

Plant material and in vitro multiplication

A tetraploid P. cablin mother plant was obtained from Guangzhou and planted in the medicinal plant garden in Guangdong Pharmaceutical University. For in vitro cultures, leaves were treated with 75% ethanol for 5 s, then with 0.1% mercuric chloride for 10–15 min, washed three times (2–3 min each) with sterile water and cultured in shoot multiplication medium: MS medium (Murashige and Skoog 1962) supplemented with 0.2 mg L−1 6-benzylaminopurine and 0.1 mg L−1 α-naphthaleneacetic acid for cluster bud multiplication. Cultures were maintained at 25 ± 2ºC with 16 h per day photoperiod at a light intensity of 60 μE m−2 s−1.

Octoploid induction

Liquid MS medium supplemented with 2% dimethyl sulfoxide and filter-sterilized colchicine (0.05, 0.1 and 0.2% final concentrations) was used for octoploid induction. Cluster buds (3–6 mm) excised from in vitro cultures were placed in MS liquid medium containing the respective concentrations of colchicine described above as well as in colchicine-free MS medium and incubated by shaking (100 rpm) at 25ºC for 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72 and 84 h. A total of 40 explants were used per treatment. Shoot apices were washed three times (2–3 min each) with sterile water and cultured in shoot multiplication medium for plant regeneration.

Flow cytometry analysis of ploidy level

The ploidy level of regenerated plants of in vitro mother cultures and colchicine-treated cultures were analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, California, USA). Cells were prepared using a method modified from Loureiro et al. (2007). Nuclei were isolated from mature leaves (0.5 cm × 1 cm) by chopping with a sharp razor blade in 2 mL of Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.2 mol L−1 Tris, 4 mmol L−1 MgCl2, 2 mmol L−1 EDTA-Na2, 86 mmol L−1 NaCl, 10 mmol L−1 Na2S2O5, 1% PVP-10 and 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 at pH 4.5. The suspension was filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer and then washed with 100 μL of Tris-HCl buffer. The nuclei were treated with RNase, stained with propidium iodide and incubated in darkness at 4ºC for 1–2 h. The stained nuclei were diluted to a concentration of 5000 nuclei per sample and analyzed for ploidy level by a flow cytometer.

Chromosome count

The ploidy level of the mother plant and in vitro polyploid plants, assessed by flow cytometry, was confirmed by chromosome count. Root tips were pretreated with ice-water mixture for 24 h, and then digested in an enzyme mixture of 4% cellulase and 4% pectinase at 35ºC for 30–100 min, washed three times in distilled water and subsequently incubated in distilled water at room temperature for 15 min. The samples were then processed using the Feulgen squash method. The tips were placed on pre-cooled microscope slides and squashed in the presence of the fixative. The slides were heated over an alcohol flame to dry the fixative, stained with fresh 5% Giemsa in Sorensen’s buffer at room temperature for 20 min, washed with a fresh stream of water and dried at room temperature. The chromosome numbers were observed under a light microscope (ZEISS Axioplan 2). A minimum of 50 metaphase cells showing well-scattered and contracted chromosomes were counted for each plantlet.

Observation of leaf characteristics

Leaf characteristics were observed in 6-month-old plants. For stomatal measurements, about 0.1 cm2 of the leaf lower epidermis was used. Four leaves were chosen from each of five tetraploid controls and each of five octoploid plants, and 20 stomata were measured per leaf.

Sample extraction and patchoulic alcohol analysis

Pulverized samples (3 g) of P. cablin were weighed accurately and extracted three times with chloroform (50 mL) in an ultrasonic bath for 20 min. The filtrate was combined and evaporated in vacuo and the residue was dissolved in 5 mL of n-hexane. Of the above solution, 1 mL and 0.05 mL of internal standard were added to a 5-mL volumetric flask and diluted to volume with n-hexane. The obtained solution was filtered through a syringe filter (0.45 μm). AT-SE54 capillary column (0.25 mm × 15 mm, 0.25 μm); carrier gas flow rate 1.0 mL min−1; keep 5 min; and injection volume of 1 μL. The content of patchouli alcohol was determined by gas chromatography (GC) method according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (China Pharmacopoeia Committee 2015).

Experimental data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS ver. 10.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Significant differences among the means were separated using the two-sample t-test at p < 0.05.

Results

Survival and growth of colchicine-treated buds

The effect of colchicine on growth of the explants was assessed 3 months after treatment (Table 1). Both apical and lateral buds were counted. Non-growing brown buds were considered to be dead.

Table 1.

Effect of different concentrations and treatment duration of colchicine on polyploidy induction (mean ± standard error) in P. cablin (all data are in percentages)

| Colchicine concentration (%) | Duration (exposure) time (h) | Treatment number | Survival number | Variation number | Variation rates (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Of initial buds | Of survival buds | |||||

| 0.05 | 12 | 40 | 84 | 14 | 34.89 ± 1.35 | 16.36 ± 1.29 |

| 24 | 40 | 71 | 21 | 52.45 ± 2.43 | 29.43 ± 0.92 | |

| 36 | 40 | 68 | 24 | 60.32 ± 2.89 | 33.94 ± 3.01 | |

| 48 | 40 | 65 | 24 | 59.56 ± 2.51 | 36.92 ± 1.02 | |

| 60 | 40 | 70 | 30 | 75.64 ± 2.78 | 41.27 ± 1.37 | |

| 72 | 40 | 61 | 34 | 85.65 ± 1.1 | 54.73 ± 2.13 | |

| 84 | 40 | 54 | 21 | 52.53 ± 2.01 | 38.89 ± 1.32 | |

| 0.1 | 12 | 40 | 57 | 19 | 47.59 ± 3.92 | 33.33 ± 3.19 |

| 24 | 40 | 42 | 16 | 40.32 ± 4.02 | 38.09 ± 3.89 | |

| 36 | 40 | 37 | 19 | 47.57 ± 4.62 | 51.35 ± 4.58 | |

| 48 | 40 | 45 | 22 | 55.68 ± 3.85 | 48.88 ± 3.58 | |

| 60 | 40 | 49 | 24 | 60.56 ± 5.01 | 48.97 ± 4.97 | |

| 72 | 40 | 35 | 20 | 50.56 ± 4.53 | 57.14 ± 4.62 | |

| 84 | 40 | 29 | 15 | 37.52 ± 3.59 | 51.72 ± 3.57 | |

| 0.2 | 12 | 40 | 45 | 20 | 50.35 ± 4.69 | 43.44 ± 5.09 |

| 24 | 40 | 35 | 17 | 42.54 ± 4.82 | 46.57 ± 5.01 | |

| 36 | 40 | 35 | 21 | 52.55 ± 3.78 | 60.75 ± 3.27 | |

| 48 | 40 | 31 | 20 | 50.29 ± 5.96 | 65.51 ± 4.91 | |

| 60 | 40 | 29 | 13 | 32.54 ± 4.82 | 42.82 ± 5.14 | |

| 72 | 40 | 23 | 12 | 30.19 ± 4.27 | 52.31 ± 4.78 | |

| 84 | 40 | 21 | 11 | 27.45 ± 4.87 | 52.38 ± 3.69 | |

Induction on MS solid medium, and the seedlings transplanted in soil for 6 months.

The seedlings both from the lateral buds and the cluster buds were in the statistical range.

The first visible effect of colchicine was the delayed growth rate of explants. The initiation of bud growth occurred within 3–4 d in untreated explants and 10–15 d in colchicine-treated explants. After a month of growth, all colchicine-treated explants had significantly shorter shoots than untreated explants(data not shown). Colchicine-treated explants also had significantly fewer lateral buds per explant than untreated explants, and the lateral buds number decreased with increasing colchicine concentrations (Table 1).

Flow cytometry analysis and chromosome counts of colchicine-treated explants

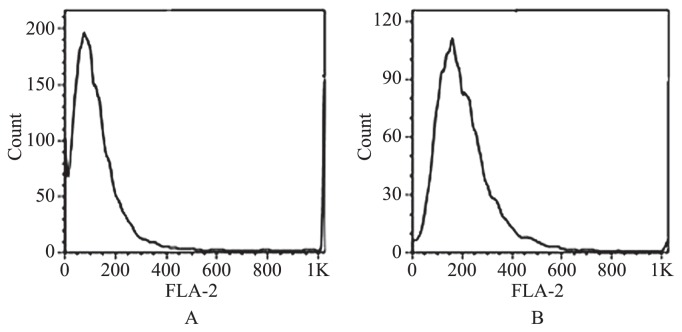

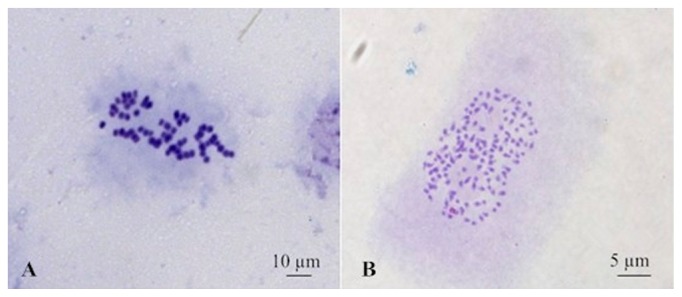

All surviving colchicine-treated explants were subjected to flow cytometry to determine their ploidy. The peak of a tetraploid control plant (4x) was set at channel 80 (Fig. 1A). The peak of the octoploid plants (8x) was expected at channel 160 (Fig. 1B). The ploidy level of the polyploid plants was confirmed by chromosome count. The tetraploid control plants had a chromosome number of 2n = 4x = 64 (Fig. 2A), whereas the octoploid plants had 2n = 8x = 128 (Fig. 2B). The highest percentage of octoploid induction was 68% and occurred in the 0.05% colchicine treatment for 72 h.

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometry histogram of P. cablin grown under greenhouse conditions for 6 months. Histogram of a tetraploid control (A) and an octoploid (B) plant.

Fig. 2.

Chromosome numbers of tetraploid (A) and octoploid (B) P. cablin.

The chromosome counts and flow cytometry indicated that 31 octoploid plantlets were obtained.

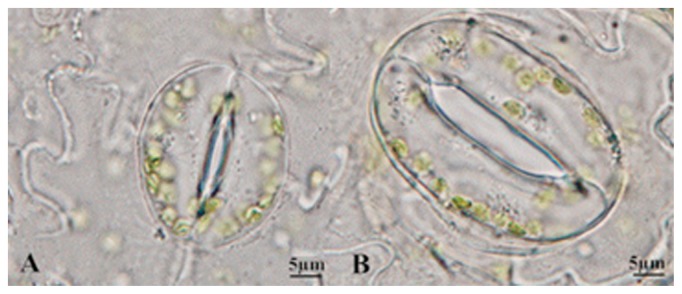

Stomatal observation

Table 2 shows the comparison of stomata characteristics between tetraploids and octoploids. The mean stomatal length and width were 41.41 and 29.07 μm, respectively, in 3-month-old octoploids, but only correspondingly 29.15 and 23.00 μm in 3-month-old tetraploids (Fig. 3, Table 2). The average stomatal frequency in tetraploids was 7.01 mm−2 and that in 3-month-old octoploids was 3.48 mm−2 (Table 2). There was an average of 6.36 chloroplasts per stomata in 3-month-old tetraploids; this number doubled to 14.04 in 3-month-old octoploids (Table 2). All stomatal characteristics of 6-month-old tetraploids and octoploids were also significantly different.

Table 2.

Stomatal characteristics of tetraploid and octoploid P. cablin

| Ploidy | Stomatal Length (μm) | Stomatal Width (μm) | Stomatal density (no./mm2) | chloroplasts number (no./stoma) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraploid (3 month) | 29.15 ± 0.48a | 23.00 ± 0.29a | 7.01 ± 0.2a | 6.36 ± 0.44a |

| Octoploid (3 month) | 41.41 ± 0.68b | 29.07 ± 0.49b | 3.48 ± 0.16b | 14.04 ± 0.45b |

| Tetraploid (6 month) | 28.33 ± 3.1a | 21.38 ± 2.43a | 23.5 ± 4.08c | 6.05 ± 1.19a |

| Octoploid (6 month) | 40.95 ± 3.38b | 27.82 ± 2.05b | 10.9 ± 2.18b | 12.3 ± 2.3b |

Values within the same column followed by different lower-case letters are significantly different according to two-sample t-test (p < 0.05).

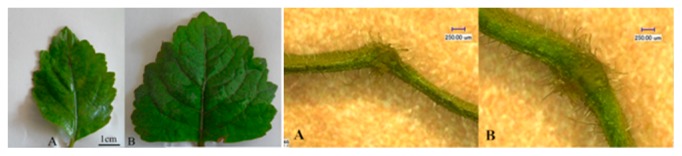

Fig. 3.

Stomata characteristics of tetraploid (A) and octoploid (B) P. cablin.

These observations are consistent with the results of some studies showing that stomatal index decreased and stomata length and width increased with increasing ploidy (Mishra 1997). The differences in stomatal characteristics between tetraploid and octoploid plantlets were significantly different according to two-sample t-test (p < 0.05).

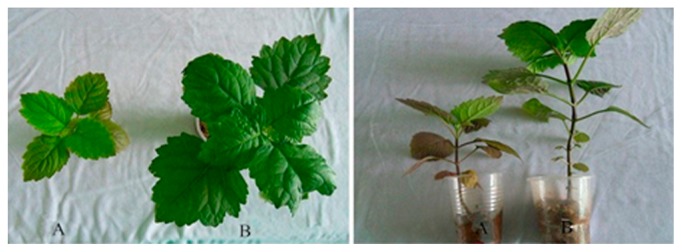

Morphological differences between tetraploid and octoploid P. cablin

The morphological features of polyploid plants were evaluated to determine whether they could be used to identify putative octoploids. In most cases, the leaves of octoploid plants appeared normal in shape compared with those of tetraploid plants, but octoploid plants with thicker stems were taller and stronger than tetraloid plants. The length and width of 30-d-old tetraploid and octoploid in vitro leaves were not significantly different (data not shown), but those of 3- and 6-month-old plants differed significantly (Table 3, Figs. 4, 5). The average leaf length was 6.55 and 7.23 cm in tetraploid and octoploid plants, respectively; and the corresponding leaf widths of 5.08 and 6.84 cm also differed. Thus the surface area was about 1.46 times greater for octoploid than for tetraploid leaves. These characteristics were also significantly different between 6-month-old tetraploid and octoploids, expect for leaf length.

Table 3.

Leaf characteristics (mean ± standard error) of tetraploid and octoploid P. cablin

| Ploidy | Leaf length (cm) | Leaf width (cm) | Leaf index | Leaf area (cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraploid (3 month) | 6.55 ± 0.21a | 5.08 ± 0.14a | 1.3 ± 0.03a | 24.17 ± 1.10a |

| Octoploid (3 month) | 7.23 ± 0.13b | 6.84 ± 0.18b | 1.06 ± 0.02b | 35.37 ± 1.15b |

| Tetraploid (6 month) | 7.14 ± 0.81b | 6.26 ± 0.84b | 1.14 ± 0.1a | 31.51 ± 4.52c |

| Octoploid (6 month) | 7.3 ± 0.9b | 7.12 ± 0.8c | 1.03 ± 0.05b | 40.23 ± 4.56d |

Values within the same column followed by different lower-case letters are significantly different according to two-sample t-test (p < 0.05).

Leaf index = leaf length/leaf width.

Fig. 4.

Plant morphology of tetraploid (A) and octoploid (B) P. cablin.

Fig. 5.

Leaves of tetraploid (A) and octoploid (B) P. cablin.

Content of patchoulic alcohol

The content of effective compounds is very important for medicinal plants. In order to evaluate the content of the effective constituent of octoploid P. cablin, herb samples of each octoploid plant were extracted and analyzed by GC.

The content of patchoulic alcohol in each octoploid line is shown in Table 4. Only two lines, 26 and 27, had a lower content of patchoulic alcohol than the control (p < 0.05). The contents of patchoulic alcohol in lines 26, 27 and in the control were 0.85, 1.38 and 3.08 mg/g, respectively. Most octoploid plants (21 lines) had a higher patchoulic alcohol content than controls; especially for line 22 with 8.02 mg/g (p < 0.01), which was 2.6 times higher than the control.

Table 4.

Content of patchoulic alcohol in octoploid P. cablin

| Strain | Content of patchoulic alcohol (mg/g) | Stain | Content of patchoulic alcohol (mg/g) | Stain | Content of patchoulic alcohol (mg/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| 1 | 3.7 ± 0.28* | 11 | 4.29 ± 0.46* | 21 | 4.47 ± 0.43* |

| 2 | 3.76 ± 0.42* | 12 | 4.62 ± 0.29* | 22 | 8.02 ± 0.38** |

| 3 | 3.2 ± 0.09 | 13 | 4.27 ± 0.29* | 23 | 5.8 ± 0.43* |

| 4 | 3.42 ± 0.03 | 14 | 5.66 ± 0.53* | 24 | 4.19 ± 0.43* |

| 5 | 4.51 ± 0.33* | 15 | 4.55 ± 0.36* | 25 | 5.44 ± 0.62* |

| 6 | 5.37 ± 0.34* | 16 | 3.18 ± 0.31 | 26 | 0.85 ± 0.034* |

| 7 | 3.53 ± 0.46* | 17 | 5.13 ± 0.29* | 27 | 1.38 ± 0.33* |

| 8 | 3.79 ± 0.27* | 18 | 3.78 ± 0.32* | 28 | 6.12 ± 0.5** |

| 9 | 2.6 ± 0.11 | 19 | 3.29 ± 0.1 | 29 | 5.79 ± 0.86* |

| 10 | 3.03 ± 0.27 | 20 | 4.8 ± 0.21* | 30 | 3.12 ± 0.21 |

| 31 | 3.13 ± 0.33 | ||||

| Original plant | 3.08 ± 0.27 | ||||

The numbers in boldface are significantly different (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Discussion

Using the chemical mutagens, colchicine, to induce polyploidy breeding is a frequently used technique, and now there are multiple polyploids of medicinal plants, such as Dioscorea zingiberensis, Centella asiatica, Angelica dahurica, Pinellia ternate, and Astragalus membranaceus.

Morphological identification, chromosome analysis, and determination of stomata are integral methods in polyploid identification; polyploidy plants have been identified by using the above three methods. As a supplementary means, flow cytometry has also been use in polyploidy identification.

The slow growth may be due to the inhibitory effect of colchicine on cell division. Both untreated and colchicine-treated explants grew equally well when sub-cultured, suggesting that colchicine only caused an initial retardation of growth, as observed in ex vitro studies (Chen and Gao 2007).

The survival rate decreased with increasing colchicine concentration and treatment time (Table 1). This inverse relationship between colchicine concentration and explant survival was expected and in agreement with ex vitro (Dwivedi et al. 1986, Sikdar and Jolly 1994) and in vitro (Chen and Gao 2007, Tang et al. 2010) studies in other plants. The concentration and immersion time of colchicine also influenced the variation rate of buds. Although the variation rate of surviving buds was the highest when immersed in 0.2% colchicine for 48 h, the survival rate and the number of lateral buds per explant was lower. So the variation effect was highest when buds were immersed in 0.05% colchicine for 72 h (Table 1).

The utility of stomatal size in distinguishing plants with different ploidy levels has been used in other plant types (Chen and Gao 2007, Hamill et al. 1992, Sikdar and Jolly 1994, Van Duren et al. 1996). We therefore concluded that stomatal observation and chloroplast enumeration represented a rapid and efficient method for screening putative octoploid plants for transplantation into the field.

In our experiments, octoploid plants of P. cablin were generated by colchicine. Of these, 21 lines showed higher productivity of patchoulic alcohol, expressed as yield of effective compounds, than the tetraploid mother plant line. These octoploid lines present a promising new tool for breeding programs aimed at increasing production of medicinal compounds from this species.

The leaf size of transplants was a useful parameter for identifying putative octoploids in P. cablin. The larger leaves of the octoploids indicated possible higher biomass and greater amounts of desirable compounds.

The major chemical constituents of P. cablin (of all ploidy levels) were determined to be patchoulic alcohol. Most octoploid plants showed higher overall productivity of patchoulic alcohol than the controls. Especially line 22 showed a significant increase of 164% in patchoulic alcohol over that of the tetraploid plant; such increases have been reported previously in artificial tetraploid plants, such as Papaver somniferum, which had an increase of 25–50% in the morphine content (Mishra et al. 2010), and Artemisia annua, which showed an increased artemisinin content of 38% (Wallaart et al. 1999). However, Gao et al. (2002) have reported that the amount of active constituents also depended on the plant genotype; in Scutellaria baicalensis, one tetraploid line exhibited an increase in baicalin of 4.6%, whereas an additional 19 lines showed reduced baicalin production (Gao et al. 2002).

Why is the content of patchoulic alcohol higher for octoploids than tetraploids? One reason is due to their higher weight for the increase of octoploids cells, on the other hand, it is speculated that genetic transcription and expression differences in octoploids lead to the increase of secondary metabolites.

In summary, an efficient colchicine-mediated technique for in vitro induction of octoploids in P. cablin had been established. The larger leaves and stomata of transplants can be used to identify putative octoploids in P. cablin. Most octoploid lines exhibited higher patchoulic alcohol contents than the controls after 6 months of cultivation and polyploidy induction could improve the medicinal value of P. cablin.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Science and Technology Plan Program of Zhongshan, P. R. China (No. 20101H019) and the Science and Technology Plan Program of Guangdong Province, P. R. China (No. [2012]145).

Literature Cited

- Chen, L.L. and Gao, S.L. (2007) In vitro tetraploid induction and generation of tetraploids from mixoploids in Astragalus membranaceus. Sci. Hortic. 112: 339–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.Y., Chen, C.B., Liang, G.L., Li, X.L., Chen, L., Wang, Z.G., Ma, X.J. and Wang, W.X. (2009) Chromosome Atlas of Major Economic Plants Genome in China: Tomus V. Chromosome Atlas of Medicinal Plants in China. 1st edn Science Press, Beijing, p. 341. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.M. and Korban, S.S. (2011) In vitro ploidy manipulation in the genomics era. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 104: 281–282. [Google Scholar]

- Cherian, M. and Kuriachan, P.I. (1993) Cytotaxonomic studies of the subtribe Pogostemoninae sensu Bentham (Labiatae) from south India. Cytologia 58: 439–444. [Google Scholar]

- China Pharmacopoeia Committee (2015) Chinese Pharmacopoeia. China Medical Science Press, Beijing, p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Dhooghe, E., Denis, S., Eeckhaut, T., Reheul, D. and Van Labeke, M.C. (2009) In vitro induction of tetraploids in ornamental Ranunculus. Euphytica 168: 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dhooghe, E., Van Laere, K., Eeckhaut, T., Leus, L. and Van Huylenbroeck, J. (2011) Mitotic chromosome doubling of plant tissues in vitro. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 104: 359–373. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Q., Wang, Z.H. and Xu, H.H. (2002) Tissue culture and rapid reproduction of Pogostemon cablin. Plant Physiol. Comm. 38: 454. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, N.K., Sikdar, A.K., Dandin, S.B., Sastriy, C.R. and Jolly, M.S. (1986) Induced tetraploidy in mulberry I. Morphological, anatomical and cytological investigations in cultivar RFS-135. Cytologia 51: 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.L., Chen, B.J. and Zhu, D.N. (2002) In vitro production and identification of autotetraploids of Scutellaria baicalensis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 70: 289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hamill, S.D., Smith, M.K. and Dodd, W.A. (1992) In vitro induction of banana autotetraploids by colchicine treatment of micropropagated diploids. Aust. J. Bot. 40: 887–896. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.J., Yang, X.Q. and Chen, K. (2009) Study on bud different and callus induction of Hainan Pachouli in vitro. J. China Pha. 18: 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.P., Gao, S.L., Chen, L.L. and Jiao, X.K. (2008) In vitro induction and identification of autotetraploids of Dioscorea zingiberensis. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Plant 44: 448–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyohara, H., Ichino, C., Kawamura, Y., Nagai, T., Sato, N. and Yamada, H. (2012) Patchouli alcohol: in vitro direct anti-influenza virus sesquiterpene in Pogostemon cablin Benth. J. Nat. Med. 66: 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavania, U.C. (1984) Chromosome Number Reports LXXXV. Taxon. 33: 756–760. [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro, J., Rodriguez, E., Doležel, J. and Santos, C. (2007) Two new nuclear isolation buffers for plant DNA flow cytometry: a test with 37 species. Ann. Bot. 100: 875–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel, T.P. and Leonhardt, K.W. (2011) In vitro polyploid induction of orchids using oryzalin. Sci. Hortic. 130: 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, M.K. (1997) Stomatal characteristics at different ploidy levels in Coffea L. Ann. Bot. 80: 689–692. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, B.K., Pathak, S., Sharma, A., Trivedi, P.K. and Shukla, S. (2010) Modulated gene expression in newly synthesized auto-tetraploid of Papaver somniferum L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 76: 447–452. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T. and Skoog, F. (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15: 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, X.L., Zeng, Q.Q., Huang, S.S., Chen, Y.Z. and Yan, Z. (2012) The protoplasts isolation and culture of Pogostemon cablin cv. Shipanensis. Guihaia 32: 669–673. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.Z., Li, G., Su, Z., Su, Z.R., Zhang, F.X. and Lai, X.P. (2011) Effect of different extract parts of Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth on in vivo anti-influenza virus. Lishizhen Med. Mater. Med. Res. 22: 2578–2579. [Google Scholar]

- Sikdar, A.K. and Jolly, M.S. (1994) Induced polyploidy in mulberry (Morus spp.): induction of tetraploids. Sericologia 34: 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.Q., Chen, D.L., Song, Z.J., He, Y.C. and Cai, D.T. (2010) In vitro induction and identification of tetraploid plants of Paulownia tomentosa. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 102: 213–220. [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi, B.R. and Bahl, J.R. (1990) A note on new chromosome number in Pogostemon cablin Benth. Cell Chromosome Res. 13: 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Van Duren, M., Morpurgo, R., Dolezel, J. and Afza, R. (1996) Induction and verification of autotetraploids in diploid banana (Musa acuminata) by in vitro techniques. Euphytica 88: 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wallaart, T.E., Pras, N. and Quax, W.J. (1999) Seasonal variations of artemisinin and its biosynthetic precursors in tetraploid Artemisia annua plants compared with the diploid wild-type. Planta Med. 65: 723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.T., Yang, Z.F., Zhao, S.S., Qin, S., Guan, W.D., Huang, Q.D., Zhao, Y.S., Lin, Q. and Mo, Z.Y. (2011) Screening of anti-H1N1 active constituents from Radix Isatidis. J. Guangzhou Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 28: 419–422. [Google Scholar]

- Watrous, S.B. and Wimber, D.E. (1988) Artificial induction of polyploidy in Paphiopedilum. Lindleyana. 3: 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wimber, D.E., Watrous, S. and Mollahan, A.J. (1987) Colchicine induced polyploidy in orchids. In: Long Beach, CA, Proceedings of the 5th World Orchid Conference, p. 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, K.H. (2001) Yesterday’s polyploids and the mystery of diploidization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. and Li, M. (2013) Induction of tetraploid plants of Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth and its quality evaluation. Phcog. J. 5: 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, S.E., He, H. and Xu, H.H. (2001) Study on the tissue culture and plant regeneration of Pogostemon cablin. Chin. Med. Mat. 24: 391–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y., He, M.L., He, F., Huang, S.M. and Yan, H.J. (2013) Chromosome sectioning optimization and chromosome counting of three cultivars of Pogostemon cablin. Guangdong Agri. Sci. 40: 121–123, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.M., Zheng, X.Q. and Sun, X.P. (1994) Plant regeneration from somatic cells of Cablin Patchouli (Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth). Chin. J. Trop. Crop 15: 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.Y., Luo, F.X., Liu, L. and Guo, F.C. (2010) In vitro induction of tetraploids in crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica L.). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 101: 41–47. [Google Scholar]