Abstract

Rose mallows belong to the Muenchhusia section of the Hibiscus genus. They represent a small group of cold tolerant North American plants and are popular ornamentals mainly because of their abundant, large and colorful flowers. Due to their geographical origin they are well suited for garden use in temperate regions worldwide. The aim of the study was to investigate hybridization barriers in crosses among cultivars of Hibiscus species from the Muenchhusia section: H. coccineus, H. laevis and H. moscheutos. Crossing barriers were identified as both pre- and post-zygotic. The analysis of pollen tube growth revealed inhibition of pollen tubes and their abnormal growth. In specific crosses the fertilization success was low. The pre-fertilization barriers did not cause a complete reproductive isolation between the hybridization partners. In relation to post-fertilization barriers, the occurrence of hybrid incompatibilities such as unviability, chlorosis, necrosis, stunted growth and albinism were the main drawback in production of hybrids. The appearance of symptoms of hybrid incompatibilities was dependent upon specific parental plants. The obtained progeny had intermediate leaf morphology and flower morphology compared to parental plants. Hybridity state was verified by morphological analysis and RAPD markers. Based on the overall plant morphology, 472 hybrid progenies were obtained.

Keywords: albinism, hybrid incompatibility, hybrid inviability, pollen tube, pre-fertilization barrier, post-fertilization barrier

Introduction

Hybridization among different species and genera is one of the most important breeding approaches used for improvement of ornamental plants. The main aim of this strategy is to merge distant gene pools, hence broadening the genetic variability. However, hybridization barriers often occur in interspecific crosses hampering production of hybrids. Traditionally two types of hybridization barriers have been defined (Morgan et al. 2011, Van Tuyl and De Jeu 1997). The first group, pre-fertilization berries, includes lack of stigma receptivity or pollen viability at the time of pollination, low adhesion and germination of pollen grains, and abnormal growth of pollen tubes in the style and ovary (Rieseberg and Carney 1998). Moreover, different abnormalities in the growth of pollen tubes can influence their ability to successfully deliver sperm cells to ovules (Winkelmann et al. 2010). The second group comprises post-fertilization barriers that affect development of hybrid embryos and further development of hybrid plants. In some cases, failure in hybridization process is due to the breakdown of endosperm development. Moreover, post-fertilization barriers often involve deleterious hybrid characteristics, collectively called hybrid incompatibilities (HIs), such as unviability, lethality, sterility, albinism and abnormality in phenotypic traits of hybrids (Johnson 2010, Kinoshita 2007). These symptoms have been associated with hyperactivation of pathogen response genes due to discrepancies among components of immune systems in Arabidopsis, tomato and lettuce (Bomblies 2010, Johnson 2010).

Hibiscus L. is a genus within the Malvaceae family. It comprises around 300 species mainly distributed in tropical and subtropical regions with a few species extending into temperate zones of the world (Akpan 2006). The species are characterized by pentamerous and regular flowers that exhibit a variety of colors. The leaf morphology is very diverse in the genus. They vary from alternate and petiolated to simple or entire, lobbed and parted (Lawton 2004). Hibiscus species produce a wide range of growth habits ranging from small trees and shrubs to annual and perennial herbs (Akpan 2006).

Hibiscus species are generally classified as either tropical or hardy types. The most appreciated tropical cultivars belong to the H. rosa-sinensis group, however, they have limited use as outdoor plants in temperate regions due to their chilling sensitivity (Lawton 2004, Vazquez-Thello et al. 1996). The hardy Hibiscus plants include cultivars derived from a few species that are mainly native to North America such as H. mutabilis and H. moscheutos and a few Asiatic species, which comprise H. syriacus (Lawton 2004, Van Laere et al. 2007).

The Hibiscus Muenchhusia section is a North American taxon that includes the five species H. coccineus, H. dasycalyx, H. grandiflorus, H. laevis and H. moscheutos, commonly known as Rose mallows. These species share common growth habit being hardy herbaceous perennials and are primarily wetland species. Rose mallows are popular ornamental plants mainly due to their abundant, large and colorful flowers. The species of the Muenchhusia section are cold resistant, and thus suitable for garden use in temperate regions. All species of the Muenchhusia section have a basic chromosome number of n = 19 and they are known to form hybrids relatively easy (Small 2004, Winters 1970). However, there is a continuous need for improvement of hardy Hibiscus cultivars in relation to their growth habit and flower characteristics.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the occurrence of hybridization barriers in crosses between hardy cultivars of Hibiscus species. We investigated the occurrence of pre- and post-fertilization barriers as well as hybrid characters of the obtained seedlings.

Materials and Methods

Plant material and sexual hybridization

Five garden cultivars belonging to three hardy Hibiscus species were used to perform reciprocal crosses. They included H. moscheutos: ‘Disco Belle’, ‘Pale Pink’ and H. moscheutos ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ as well as cultivars of H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. laevis—an unnamed breeding line. Plants were propagated from seeds at Graff Breeding A/S, Sabro, Denmark and then transported to University of Copenhagen, Taastrup, Denmark, where they were maintained in the green-house under 16/8 h photoperiod and 22/18ºC ± 4ºC, day/night with additional light of 180 μmol s−1 m−2 (Philips Master SON-T PIA Green Power 400 W, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). The plants were irrigated weekly with fertilizer (Pioneer NPK Makro 14-3-23, Tilst, Denmark) with an electrical conductivity of 1.3 mS cm−1.

Interspecific crosses were performed from June to August in 2012 and 2013 using six to ten plants per genotype. Flowers were emasculated in the bud stage and hand pollinated. Pollination was performed by applying fresh pollen on the stigma of a fully open flower. An overview of the performed crosses is given in Table 1. The flowers left for natural self-pollination served as controls to determine self-incompatibility of the plants.

Table 1.

Characterization of interspecific crosses in relation to pollen tube growth and fruit, seed and plant production

| Cross combination | Pollen tubes1 | No. of pollinated flowers | Fruit set2 (%) | Av. no. of seeds/ fruit (S.E.) | Germination percentage (%) (S.E) | Seedling survival (%) (S.E) | Seedlings/ plants with HIs3 (%) | Total adult plants | Total hybrids4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Stigma | Ovary | |||||||||

| H. coccineus × H. laevis reciprocal crosses | ||||||||||

| H. c. ‘Red Star’5 × H. laevis | 5/5*** | 5/5* | 109 | 8.2 | 16.9 (3.6) | 96.0 (2.3) | 93.0 (1.5) | 0 | 67 | 67 |

| H. laevis × H. cocc. ‘Red Star’ | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 69 | 13 | 39.6 (4.8) | 97.3 (1.3) | 93.1 (3.7) | 0 | 68 | 68 |

|

| ||||||||||

| H. coccineus × H. moscheutos reciprocal crosses | ||||||||||

| H. c. ‘Red Star’ × H. m.6 ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 90 | 36.7 | 23.1 (1.6) | 96.0 (2.3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 100 | 0 | – |

| H. c. ‘Red Star’ × H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ | 5/5** | 5/5* | 68 | 19.1 | 15.8 (2.8) | 88.0 (10.1) | 93.3 (6.7) | 100 | 61 | 60 |

| H. c. ‘Red Star’ × H. m. ‘Pale Pink’ | 2/5* | 1/5* | 110 | 11.8 | 13.8 (2.0) | 54.7 (5.8) | 92.5 (0.8) | 0 | 38 | 38 |

| H. m. ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ × H. c. ‘Red Star’ | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 62 | 64.5 | 73.6 (2.6) | 80.0 (12.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 100 | 0 | – |

| H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ × H. c. ‘Red Star’ | 5/5** | 3/5** | 98 | 2 | 58.0 (9.0) | 56.0 (6.1) | 88.2 (11.8) | 100 | 36 | 27 |

| H. m. ‘Pale Pink’ × H. c. ‘Red Star’ | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 73 | 41.1 | 29.3 (1.5) | 54.7 (3.5) | 93.3 (6.7) | 0 | 38 | 38 |

|

| ||||||||||

| H. laevis × H. moscheutos reciprocal crosses | ||||||||||

| H. laevis × H. m. ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 60 | 28.3 | 23.5 (2.2) | 92.0 (6.1) | 4.7 (2.9) | 96 | 3 | 0 |

| H. laevis × H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 67 | 35.8 | 33.0 (1.8) | 94.7 (3.5) | 98.5 (1.5) | 0 | 70 | 69 |

| H. laevis × H. m. ‘Pale Pink’ | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 60 | 31.7 | 36.1 (1.9) | 44.0 (15.1) | 96.1 (3.9) | 0 | 31 | 30 |

| H. m. ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ × H. laevis | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 66 | 62.1 | 93.5 (2.9) | 26.7 (10.9) | 0.0 (0.0) | 100 | 0 | – |

| H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ × H. laevis | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 118 | 26.3 | 52.9 (3.1) | 54.7 (17.3) | 83.3 (8.5) | 31 | 32 | 29 |

| H. m. ‘Pale Pink’ × H. laevis | 5/5*** | 5/5*** | 64 | 75 | 34.5 (1.4) | 64.0 (4.0) | 95.6 (4.4) | 0 | 46 | 46 |

Pollen tubes were examined two places in the pistil: stigma and in the entrance to the ovary, the numbers indicate no. of pistils in which pollen tubes were observed, asterisks indicate number of observed pollen tubes: * up to 20 pollen tubes ** 20 to dozens pollen tubes *** hundreds pollen tubes;

No. of fruits/ no. of pollinated flowers;

HIs: hybrid incompatibilities;

Based on morphological observations;

H. c.: H. coccineus;

H. m.: H. moscheutos.

Pollen viability

Pollen was collected at the point of anther dehiscence i.e. in the day of flower opening before noon. Pollen from five flowers was immersed in a drop of 1% (w/v) acetocarmine solution and examined under a light microscope (Leitz DMRD, Leica, Germany). Pollen grains were classified as viable when stained red and unviable when unstained (Singh 2002). At least 100 pollen grains were analyzed per genotype. Each experiment was performed once in three technical replicates. The significance of differences was determined using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (HSD) in the SPSS 22.0 for Windows statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Pollen tube growth

Pollen germination and growth of pollen tubes were examined according to Kuligowska et al. (2015b). Pistils were softened for 20 minutes. Pollen tubes were examined with fluorescence microscope (Leica DM2000 LED, Leica, Germany; excitation filter BP 340–360 nm) equipped with a digital camera (Leica DFC420, Leica, Germany). The relative numbers of pollen tubes was assessed in two parts of the pistil—stigma and at the entrance to the ovary. Numbers of tubes were quantified according to the criteria: *—up to 20 pollen tubes, **—20 to dozens pollen tubes, ***—dozens to hundreds pollen tubes.

Fruit and seed set, seed germination and plant production

Fruit and seed set were evaluated around 60 days after pollination. Number of fruits and average number of seeds were registered. To determine germination percentage, 20 seeds in three replicates were sown in peat in the greenhouse with conditions as described for parental species. Number of seedlings and seedling survival was determined one month after seed sowing. Number of obtained plants and hybrids as well as plants with HIs was recorded.

Evaluation of hybrid incompatibilities

After germination plants were transplanted and were grown in the greenhouse as described for parental species. The numbers of plants exhibiting symptoms of HIs i.e. chlorosis, necrosis, stunted growth and albinism were determined following visual assessments of seedlings and adults plants.

Morphology of hybrids

The progenies obtained from crosses were morphologically analyzed. Leaf morphology, flower morphology and flower color of F1 plants that had intermediate phenotype compared to the parental plants were determined.

Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA analysis

For each cross-combination, the DNA from four individuals of the progeny exhibiting intermediate phenotype and parental plants were used to compare the amplification products using the RAPD technique (Williams et al. 1990).

DNA was extracted from 150 mg fresh leaf tissue. The leaf tissue was frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a powder. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Due to the large quantity of polysaccharides present in the extract the volume of AP1 buffer and P3 buffer were increased to 500 μl and 150 μl, respectively, and 0.02% (w/v) Polyvinylpyrrolidone (40,000) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and 3.75% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) were added to AP1 buffer to prevent polyphenol oxidation. The DNA concentration was determined using NanoDrop1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Amplification reactions were carried out in a volume of 20 μl containing 25 μM TAPS (pH 9.3), 50 μM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM DTT, 100 μM [H3]-dTTP, 0.25 mg/ml activated salmon sperm DNA, 2% (v/v) DMSO, 200 μM of each dNTP, 1 μM primer, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Ex Taq, TAKARA BIO INC., Shiga, Japan) and 50 ng plant genomic DNA in thermal cycler (MyCycler, Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). The selection of reaction conditions was made following a preliminary study in which different concentrations of polymerase, primer and template DNA were tested (data not shown).

Ten random decamer primers were tested and four primers (A01, A07, A08, A09; primer kit A, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) were selected depending on specific cross-combinations (Table 2). Thermal cycling was conducted with 5 min initial denaturation at 94ºC, followed by 45 cycles of 1 min at 94ºC, 1 min at 35ºC and 2 min at 72ºC, and a final extension step for 10 min at 72ºC. Amplification products were separated by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels in 1× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 20 mM glacial acetic acid; pH 8.4), detected by staining with Gelred (Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA) and visualized under UV light. The banding patterns were evaluated by visual inspection. All amplification reactions were repeated twice. Only bands present in both amplification reactions were considered in the analysis. Plants were classified as hybrids when at least one male-specific band was present in the banding profile of the progeny.

Table 2.

RAPD markers used for hybrid confirmation with the respective number of bands obtained for female and male parents, both parents, and the total number of bands

| Cross combination | Primer | ♀ | ♂ | Both | Total number of bands | No. of female-specific bands in the progeny1 | No. of male-specific bands in the progeny1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. c.2 ‘Red Star’ × H. laevis | A07 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 3 |

| H. laevis × H. c. ‘Red Star’ | A07 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 2 or 3 | 1 |

| H. c. ‘Red Star’ × H. m.3 ‘Disco Belle’ | A09 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 1 or 2 | 1 |

| H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ × H. c. ‘Red Star’ | A07 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 1 or 2 |

| H. c. ‘Red Star’ × H. m. ‘Pale Pink’ | A07 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 1 or 2 |

| H. m. ‘Pale Pink’ × H. c. ‘Red Star’ | A07 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 2 |

| H. laevis × H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ | A08 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ × H. laevis | A07 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 2 |

| H. laevis × H. m. ‘Pale Pink’ | A07 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 11 | 2 or 3 | 1 |

| H. m. ‘Pale Pink’ × H. laevis | A01 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

based on 5 F1 plants;

H. c.: H. coccineus;

H. m.: H. moscheutos.

Results

Pollen viability

The pollen viability was high for all tested cultivars. Levels of pollen viability were found to be 87.5% ± 2.5% for H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’, 88.0% ± 1.7% for H. moscheutos ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’, 88.2% ± 2.2% for H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’, 92.5% ± 2.9% for H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and 95.5% ± 1.2% for H. laevis. Pollen viability was not significantly different between tested cultivars.

Pollen tube growth

The analysis of pollen tube growth revealed lower numbers of pollen tubes in the stigmas from three cross-combinations compared to other crosses. They included reciprocal crosses between H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ as well as crosses between H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’ (Table 1). The numbers of pollen tubes reaching the ovaries were lower in four crosses: H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’, H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ × H. coccineus ‘Red Star’, H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’ and H. coccineus × H. laevis. Additionally, in crosses between H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’ as well as H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ and H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ no growth of pollen tubes was observed in some of the pistils (Table 1).

Qualitative analysis of pollen tube germination and growth revealed occurrence of different abnormalities in all tested interspecific crosses. They included germination of multiple pollen tubes from single pollen grains (Fig. 1A), branching of pollen tubes (Fig. 1B) and occurrence of spiky pollen tubes (Fig. 1C). Normal pollen tubes were also observed in high numbers. Thus, the normal pollen tubes were growing through the style and entering ovaries without any disruption.

Fig. 1.

Abnormal pollen germination and pollen tube growth. (A) Pollen grains of H. laevis on stigma of H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’, abnormal germination with visible multiple pollen tubes emerging from single pollen grains. (B) Branching of pollen tube, H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’. (C) Spiky pollen tube, H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. moscheutos ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’; Scale bars: 100 μm.

Self-pollinations and intraspecific pollinations of parental cultivars revealed germination of multiple pollen tubes from single pollen grains but in less extend compared to interspecific crosses. No other abnormalities were observed in control pollinations (data not shown).

Fruit and seed set, seed germination and plant production

The lowest fruit set was observed in the cross between H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ and H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ (2.0%). The values lower than 20% were obtained following reciprocal crosses between H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. laevis, crosses between H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ as well as H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and ‘Pale Pink’ (Table 1).

The lowest observed average number of seeds (less than 20) was found in three cross-combinations also characterized by low fruit set. They were: H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. laevis, H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ and H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × ‘Pale Pink’ (Table 1).

Germination rate of seeds was generally high (around 50% or higher) for all examined cross-combinations. The only exception was observed for crosses between H. moscheutos ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ × H. laevis, where the germination rate was 26.7 ± 10.9 (Table 1).

No abnormal seeds were obtained following interspecific crosses.

Survival of seedlings was generally high for all cross-combinations (from 83.3 ± 8.5 for H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ × H. laevis to 98.5 ± 1.5 for H. laevis × H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’) except the crosses where H. moscheutos ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ was used as one of the parental plants. In these crosses no seedling of intermediate phenotype developed into an adult plant (Table 1).

In our study selected cultivars could be easily self-pollinated and yielded high fruit and seed set in intraspecific crosses (data not shown).

Evaluation of hybrid incompatibilities

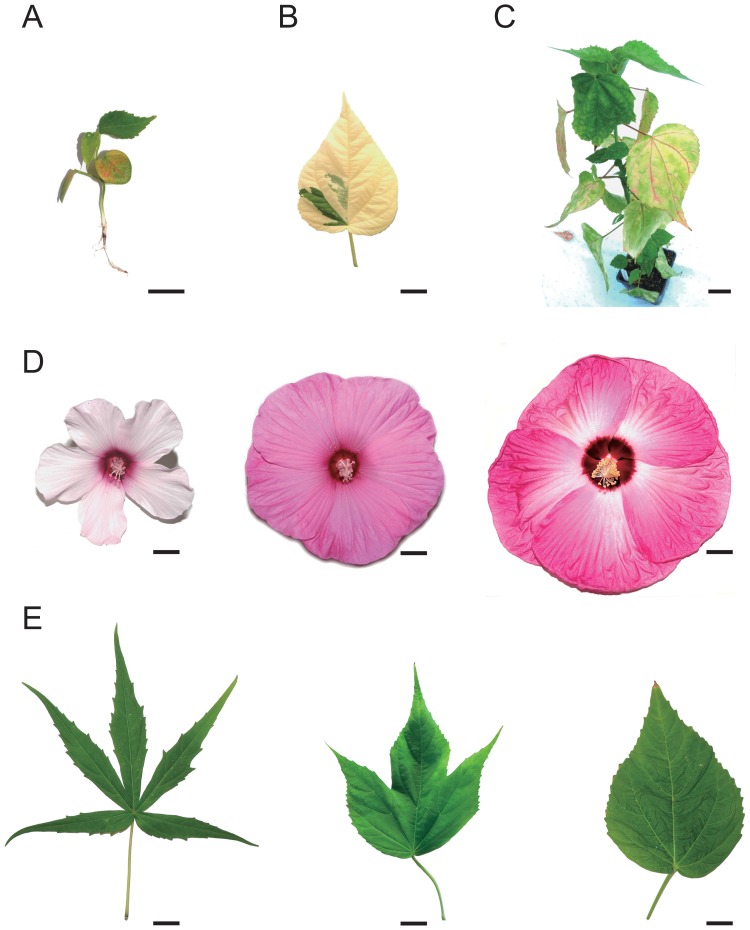

Following several cross-combinations, the obtained hybrids demonstrated signs of HIs. In the crosses where H. moscheutos ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ was used either as a paternal or maternal plant, all obtained seedlings showed signs of chlorosis and necrosis (Fig. 2A). They eventually died after developing one pair of true leaves (Table 1— seedling survival). Crosses between H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ × H. laevis resulted in 9 out of 29 (31%) plants exhibiting partial albinism (Fig. 2B). The progeny obtained after reciprocal crosses between H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ exhibited stunted growth, chlorosis and necrosis (Fig. 2C). These symptoms became more severe during the growth of the plants. The remaining crosses yielded vigorously growing plants.

Fig. 2.

Hybrid incompatibilities and morphology of Hibiscus hybrids. (A) Two months old seedlings from cross H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. moscheutos ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ showing signs of chlorosis and necrosis. (B) Partial albinism of interspecific hybrid from cross between H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ and H. laevis. (C) Adult interspecific hybrid with signs of chlorosis and stunted growth. (D) Flower morphology of parental cultivars: H. laevis (♀) (left) and H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ (♂) (right) and their representative interspecific hybrid (middle). (E) Leaf morphology of parental cultivars: H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ (♀) (left) and H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ (♂) (right) and their representative interspecific hybrid (middle). Scale bars A, B, D, E: 2 cm, C: 10 cm.

Morphological assessment

The adult plants obtained after interspecific crosses mainly exhibited intermediate characteristics. The percentage of plants with intermediate phenotype is presented in Table 1. The flower characteristics were intermediate between both hybridization partners in respect to petal shapes. Progeny resulting from crosses where H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ contributed as one of the parents resulted in red flowers. The plants obtained from reciprocal crosses between H. laevis and H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ had intermediate pink color. An example of hybrid flower compared to parental plants is shown in Fig. 2D.

The leaf morphologies had clearly intermediate shapes between parental genotypes (Table 3). Reciprocal crosses between H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’ as well as H. laevis resulted in palmate leaves with indentations of lesser deepness than H. coccineus ‘Red Star’. When H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ was crossed with H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ that has deltoid to cordate leaves, the progeny exhibited lobed leaves with depth of indentations depending on the maternal genotype. All the reciprocal crosses between H. laevis and H. moscheutos resulted in lobed leaves, while the depth of indentation depended on the specific cross-combination. An example of hybrid leaf compared to parental plants is shown in Fig. 2E.

Table 3.

General characterization of leaf shapes of parental cultivars and hybrids

| Parental cultivars and hybrids | Leaf shape |

|---|---|

| H. c.‘Red Star’ | Digitate |

| H. laevis | Hastate |

| H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ | Deltoid to cordate |

| H. m. ‘Pale pink’ | Deltoid with 3 lobes, shallow indentation |

| H. c.‘Red Star’ × H. laevis | Palmetly-lobed, 5 lobes |

| H. laevis × H. c.‘Red Star’ | Palmetly-lobed, 3–5 lobes |

| H. c.‘Red Star’ × H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ | Deltoid to cordate, one pair of lobes, deep indentation |

| H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ × H. c. ‘Red Star’ | Deltoid to cordate, one pair of shallow lobes, shallow indentation |

| H. c. ‘Red Star’ × H. m. ‘Pale pink’ | Palmetly-lobed, 3–5 lobes, deep indentation |

| H. m. ‘Pale pink’ × H. c. ‘Red Star’ | Palmetly-lobed, 3–5 lobes, deep indentation |

| H. laevis × H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ | Deltoid to cordate, sometimes with a pair of small lobes |

| H. m. ‘Disco Belle’ × H. laevis | Deltoid to cordate, sometimes with a pair of small lobes |

| H. laevis × H. m. ‘Pale pink’ | Deltoid, usually with one pair of small lobes |

| H. m. ‘Pale pink’ × H. laevis | Deltoid, usually with one pair of small lobes |

H. c.: H. coccineus

H. m.: H. moscheutos.

Based on the overall plant morphology, 472 hybrid progenies were obtained in the study.

RAPD analysis

Four selected RAPD primers generated informative bands using RAPD analysis to confirm hybridity of the progeny at the molecular level. The numbers of bands obtained for parental species and polymorphic bands in specific cross combinations are included in Table 2. Total number of bands is the sum of the bands present in female and male parents subtracted from the number of bands shared by both parents.

The band pattern was evaluated and all analyzed plants were verified as hybrids. A representative example of confirmation of hybrid status is presented in Fig. 3. Male-informative bands are present in the sample of the progeny, confirming hybrid origin of the plants.

Fig. 3.

RAPD binding pattern of hybrid plant (H) obtained from the cross between H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’ (♀) and H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ (♂) with the primer A07, M—100 bp ladder, N—negative control; arrows indicate female and male parent-specific markers.

Discussion

The objective of the study was to investigate the occurrence of hybridization barriers in interspecific crosses among cultivars belonging to Hibiscus species section Muenchhusia. In our study control pollinations yielded high fruit and seed set (data not shown). The pollen viability was high for all examined parental genotypes, thus pollen viability is not a limiting factor during hybridization. The only problematic cultivar was H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ that was characterized by low fertility despite high pollen viability. Nevertheless, we can conclude that self-incompatibility did not occur in the cultivars used in the current investigation.

In four crosses of H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ we observed lower numbers of pollen tubes or even total lack of pollen tubes in the pistils (Table 1). The pollen adhesion is a first step of reproduction that relies on successful interaction between pollen and stigma. This stage is especially important in species with dry stigma type as the one occurring in Hibiscus. Furthermore, pollen germination on stigma is dependent upon pollen rehydration and controlled by both physiological and genetic factors. Thus, pollen-stigma interactions determine the first selective barrier for successful pollen tube growth in the pistil tissue (Gao et al. 2010). Low numbers of pollen tubes in stigmas can indicate disturbed adhesion and germination of pollen in our crosses. Further impaired growth of pollen tubes to the ovaries suggests specific differences in pollen-pistil interactions. Different factors such as components of extracellular matrix, water gradient potential, concentration gradients of Ca2+, concentration of γ-aminobutyric acid, lipid molecules and proteins in the style are likely to influence the growth of pollen tubes (Gao et al. 2010, Swanson et al. 2004). Additional evidence for the disruption of pollen tube growth in our crosses comes from microscopic analysis that revealed the occurrence of a number of abnormalities (Fig. 1). A similar situation was observed in interspecific crosses among H. rosa-sinensis, H. syriacus and H. moscheutos (Kuligowska et al. 2012), Tulipa species (Van Creij et al. 1997) and within the Vigna genus (Barone et al. 1992).

Low numbers of pollen tubes and lack of pollen tubes in the pistil corresponded to lower fruit set and number of seeds in crosses between H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. laevis, H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. moscheutos ‘Pale Pink’ and H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ × H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’. In the crosses between H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ and H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ the low fruit set is likely a result of impaired pollen tube growth (Table 1).

When H. moscheutos ssp. palustris ‘Pink Mallow’ was used as hybridization partners in reciprocal crosses with both H. laevis and H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ the obtained seedlings exhibited symptoms similar to HIs and as a result died shortly after germination. Stunted growth and chlorosis were also observed in plants resulting from reciprocal crosses of H. coccineus ‘Red Star’ and H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle” (Table 1). HIs occurring after interspecific hybridization are due to genomic conflicts i.e. the situation when different parts of the genome of the same organism have conflicting genetics. This is considered to be a byproduct of genetic divergence between hybridization partners (Johnson 2010). Similar HIs were reported in hybrids of Capsicum (Inai et al. 1993), Oryza (Chu and Oka 1972) and Solanum (Sawant 1956).

In crosses between H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ and H. laevis, 31% of the progeny exhibited partial albinism (Fig. 3B). Albinism is a frequently occurring HI in hybrids and has been reported among others for Hibiscus (Van Laere et al. 2007), Lonicera (Miyashita and Hoshino 2010) and Campanula (Röper et al. 2015). In case of the crosses between H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ and H. laevis, the albinism is likely a result of improper interactions between nuclear genes from the male parent and cytoplasmic elements from the maternal plants (Bomblies and Weigel 2007). Thus, the appearance of HIs was only present in this cross when H. moscheutos ‘Disco Belle’ was used as maternal plant.

Based on hybridization and phylogenetic studies, the species within section Muenchhusia can be divided into two groups. It was stated that plants within the groups hybridize easily, while intergroup hybridization is usually hampered by hybridization barriers. According to the division H. moscheutos belongs to group I, while H. coccinues and H. laevis belong to group II (Small 2004, Wise and Menzel 1971). Our results can only partly confirm previous reports about reproductive isolation. A possible explanation of the differences in hybrid productivity in crosses among H. moscheutos cultivars and H. coccineus as well as H. laevis cultivars might be their specific genetic background for hybrid production.

The morphological observations of the obtained progeny revealed that the majority of plants had intermediate phenotypes between both hybridization partners. Only a small fraction of these plants had maternal-like phenotypes (Table 1) that can be due to unintentional self-pollination. The occurrence of intermediate phenotypes of the progeny is a typical feature of interspecific hybridization and was described for several plant genera such as Dianthus (Nimura et al. 2003), Chrysanthemum (Cheng et al. 2011), Streptocarpus (Afkhami-Sarvestani et al. 2012) and Kalanchoë (Kuligowska et al. 2015a). It can be explained by inheritance pattern based on polygenic control with additive effects (Schwarzbach et al. 2001). All plants obtained from crosses where H. coccineus was used as one of the parents had red flowers suggesting dominance of this trait. Several of the obtained interspecific hybrids exhibited favorable characteristics such as vigorous growth and branching that can be useful for development of new cultivars.

Future analysis of the obtained interspecific hybrids will require evaluation of their cold tolerance and environmental requirements for flowering such as thermal and photoperiodic conditions. The Hibiscus plants used in our experiments are North American species and their range of latitude is between 27 and 42ºN that corresponds to hardiness zones from 10 to 5 (down to −26.1ºC or −15ºF ) (Magarey et al. 2008, Warner and Erwin 2001). At the same time these species have high requirements in relation to light intensities (Warner and Erwin 2003). Therefore, the usefulness of species and hybrids in different locations such as Northern Europe can be limited. Screening of our hybrids for their environmental requirements is of great importance.

The interspecific hybrids produced during the study have provided insights into breeding of hardy Hibiscus species and presence of hybridization barriers. The main drawback in production of hybrid progeny was the presence of post-fertilization barriers associated with the occurrence of HIs that limit the usefulness of the obtained plants for further breeding purposes. A clear influence of the genetic background of the hybridization partners was recognized for the production of hybrids. Moreover, the cross direction was another factor that influenced the creation of progeny. Thus, for future breeding activities it is necessary to screen available cultivars of hardy Hibiscus species and perform reciprocal crosses.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Graff Breeding A/S, Sabro, Denmark, for providing plant material, Dr David Mackenzie and Dr Gregorio Barba Espin for proofreading the manuscript. This project was a part of the innovation consortium “Innovative Plants” funded by the Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation.

Literature Cited

- Afkhami-Sarvestani, R., Serek, M. and Winkelmann, T. (2012) Interspecific crosses within the Streptocarpus subgenus Streptocarpella and intergeneric crosses between Streptocarpella and Saintpaulia ionantha genotypes. Sci. Hortic. 148: 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Akpan, G.A. (2006) Hibiscus. In: Anderson, N.O. (ed.) Flower Breeding and Genetics: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for the 21st Century, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 479–489. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, A., Del Giudice, A. and Ng, N. (1992) Barriers to interspecific hybridization between Vigna unguiculata and Vigna vexillata. Sex. Plant Reprod. 5: 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bomblies, K. and Weigel, D. (2007) Hybrid necrosis: autoimmunity as a potential gene-flow barrier in plant species. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 382–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomblies, K. (2010) Doomed lovers: mechanisms of isolation and incompatibility in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 61: 109–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X., Chen, S., Chen, F., Deng, Y., Fang, W., Tang, F., Liu, Z. and Shao, W. (2011) Creating novel chrysanthemum germplasm via interspecific hybridization and backcrossing. Euphytica 177: 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Y.-E. and Oka, H.-I. (1972) The distribution and effects of genes causing F1 weakness in Oryza breviligulata and O. glaberrima. Genetics 70: 163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.-Q., Zhu, D. and Zhang, X. (2010) Stigma factors regulating self-compatible pollination. Front. Biol. 5: 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Inai, S., Ishikawa, K., Nunomura, O. and Ikehashi, H. (1993) Genetic analysis of stunted growth by nuclear-cytoplasmic interaction in interspecific hybrids of Capsicum by using RAPD markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 87: 416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N.A. (2010) Hybrid incompatibility genes: remnants of a genomic battlefield? Trends Genet. 26: 317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, T. (2007) Reproductive barrier and genomic imprinting in the endosperm of flowering plants. Genes Genet. Syst. 82: 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuligowska, K., Simonsen, M., Lütken, H., Müller, R. and Christensen, B. (2012) Breeding of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis for garden use in Denmark. Acta Hortic. 990: 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kuligowska, K., Lütken, H., Christensen, B. and Müller, R. (2015a) Quantitative and qualitative characterization of novel features of Kalanchoë interspecific hybrids. Euphytica 205: 927–940. [Google Scholar]

- Kuligowska, K., Lütken, H., Christensen, B., Skovgaard, I., Linde, M., Winkelmann, T. and Müller, R. (2015b) Evaluation of reproductive barriers contributes to the development of novel interspecific hybrids in the Kalanchoë genus. BMC Plant Biol. 15: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, B.P. (2004) Hibiscus: hardy and tropical plants for the garden. Timber Press; Portland, OR: p.160. [Google Scholar]

- Magarey, R.D., Borchert, D.M. and Schlegel, J.W. (2008) Global plant hardiness zones for phytosanitary risk analysis. Sci. Agr. 65: 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita, T. and Hoshino, Y. (2010) Interspecific hybridization in Lonicera caerulea and Lonicera gracilipes: The occurrence of green/albino plants by reciprocal crossing. Sci. Hortic. 125: 692–699. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, E.R., Timmerman-Vaughan, G.M., Conner, A.J., Griffin, W.B. and Pickering, R. (2011) Plant interspecific hybridization: outcomes and issues at the intersection of species. Plant Breed. Rev. 34: 161–220. [Google Scholar]

- Nimura, M., Kato, J., Mii, M. and Morioka, K. (2003) Unilateral compatibility and genotypic difference in crossability in interspecific hybridization between Dianthus caryophyllus L. and Dianthus japonicus Thunb. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106: 1164–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg, L.H. and Carney, S.E. (1998) Plant hybridization. New Phytol. 140: 599–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röper, A.-C., Lütken, H., Christensen, B., Boutilier, K., Petersen, K. and Müller, R. (2015) Production of interspecific Campanula hybrids by ovule culture: exploring the effect of ovule isolation time. Euphytica 203: 643–657. [Google Scholar]

- Sawant, A.C. (1956) Semilethal complementary factors in a tomato species hybrid. Evolution 10: 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzbach, A.E., Donovan, L.A. and Rieseberg, L.H. (2001) Transgressive character expression in a hybrid sunflower species. Am. J. Bot. 88: 270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.J. (2002) Pollen Staining. In: Singh, R.J. (ed.) Plant cytogenetics, CRC press, Boca Raton, pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Small, R.L. (2004) Phylogeny of Hibiscus sect. Muenchhusia (Malvaceae) based on chloroplast rpL16 and ndhF, and nuclear ITS and GBSSI sequences. Syst. Bot. 29: 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, R., Edlund, A.F. and Preuss, D. (2004) Species specificity in pollen-pistil interactions. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38: 793–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Creij, M.G.M., Kerckhoffs, D.M.F.J. and Van Tuyl, J.M. (1997) Interspecific crosses in the genus Tulipa L.: identification of pre-fertilization barriers. Sex. Plant Reprod. 10: 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laere, K., Van Huylenbroeck, J.M. and Van Bockstaele, E. (2007) Interspecific hybridisation between Hibiscus syriacus, Hibiscus sinosyriacus and Hibiscus paramutabilis. Euphytica 155: 271–283. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tuyl, J.M. and De Jeu, M.J. (1997) Methods for overcoming interspecific crossing barriers. In: Shivanna, K.R. and Sawhney V.K. (eds.) Pollen biotechnology for crop production and improvment, Cambridge Univ. Press, London, UK, pp. 273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Thello, A., Yang, L.J., Hidaka, M. and Uozumi, T. (1996) Inherited chilling tolerance in somatic hybrids of transgenic Hibiscus rosa-sinensis × transgenic Lavatera thuringiaca selected by double-antibiotic resistance. Plant Cell Rep. 15: 506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner, R. and Erwin, J. (2001) Variation in floral induction requirements of Hibiscus sp. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 126: 262–268. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, R. and Erwin, J. (2003) Effect of photoperiod and daily light integral on flowering of five Hibiscus sp. Sci. Hortic. 97: 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.G., Kubelik, A.R., Livak, K.J., Rafalski, J.A. and Tingey, S.V. (1990) DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 6531–6535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelmann, T., Doil, A., Reinhardt, S. and Ewald, A. (2010) Embryo Rescue. In: Davey, M.R. and Anthony P. (eds.) Plant Cell Culture: Essential Methods, John Wiley & Sons, London, UK, pp. 79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Winters, H.F. (1970) Our hardy Hibiscus species as ornamentals. Econ. Bot. 24: 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wise, D.A. and Menzel, M.Y. (1971) Genetic affinities of the North American species of Hibiscus sect. Trionum. Brittonia 23: 425–437. [Google Scholar]