Abstract

This chapter summarizes current ideas about the intracellular signaling that drives platelet responses to vascular injury. After a brief overview of platelet activation intended to place the signaling pathways into context, the first section considers the early events of platelet activation leading up to integrin activation and platelet aggregation. The focus is on the G protein-mediated events utilized by agonists such as thrombin and ADP, and the tyrosine kinase-based signaling triggered by collagen. The second section considers the events that occur after integrin engagement, some of which are dependent on close physical contact between platelets. A third section addresses the regulatory events that help to avoid unprovoked or excessive platelet activation, after which the final section briefly considers individual variations in platelet reactivity and the role of platelet signaling in the innate immune response and embryonic development.

Keywords: G proteins, G protein coupled receptors, Signal transduction, Thrombin, Collagen, ADP

1 Overview

The steps in stable platelet plug formation can be summarized in a three stage model as initiation, extension and stabilization, each of which is supported by signaling events within the platelet. Initiation occurs when moving platelets become tethered to and activated by collagen/von Willebrand factor (VWF) complexes within the injured vessel wall. This produces a platelet monolayer that supports the subsequent adhesion of activated platelets to each other. Extension occurs when additional platelets adhere to the initial monolayer and become activated. Thrombin, ADP and thromboxane A2 (TxA2) play an important role in this step, activating platelets via cell surface receptors coupled to heterotrimeric G proteins. Subsequent intracellular signaling activates integrin αIIbβ3 (glycoprotein (GP) IIb–IIIa in older literature) on the platelet surface, thereby enabling cohesion between platelets. Stabilization refers to the late events that help to consolidate the platelet plug and prevent premature disaggregation, in part by amplifying signaling within the platelet. Examples include outside-in signaling through integrins and contact-dependent signaling through receptors whose ligands are located on the surface of adjacent platelets. The net result is a hemostatic plug composed of activated platelets embedded within a cross-linked fibrin mesh, a structure stable enough to withstand the forces generated by flowing blood in the arterial circulation.

This three stage model arises from studies on platelets from individuals with monogenic disorders of platelet function and from mouse models in which genes of interest have been knocked out. However, recent observations suggest that the model is overly simplistic in presenting platelet accumulation after injury as a linear, unstoppable and nonreversible series of events. In fact, there is now ample evidence for spatial as well as temporal heterogeneity within a growing hemostatic plug (Yang et al. 2002; Reininger et al. 2006; Ruggeri et al. 2006; Nesbitt et al. 2009; Bellido-Martin et al. 2011; Brass et al. 2011). This means that at any given time following injury there are fully activated platelets as well as minimally activated platelets, not all of which will inevitably become fully activated. Furthermore, with the passage of time, incorporated platelets draw closer together and many remain in stable contact with each other. This allows contact-dependent signaling to occur and produces a sheltered environment in which soluble molecules can accumulate. Thus, a more updated view of platelet activation needs to be less ordered than the three stage model, reflect differences in the extent of activation of individual platelets and incorporate the consequences of platelet:platelet interactions in a three dimensional space.

1.1 Molecular Events

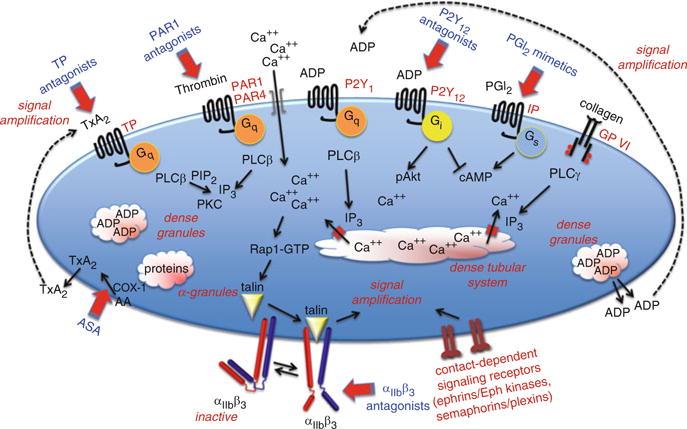

Under steady state conditions, platelets circulate in an environment bordered largely by a continuous monolayer of endothelial cells. They move freely, but are quiescent. Once vascular injury has occurred, platelets are principally activated by locally exposed collagen, locally generated thrombin, platelet-derived thromboxane A2 (TxA2) and ADP that is either secreted from platelet dense granules or released from damaged cells. VWF serves as an essential accessory molecule. In the pre-injury state, VWF is found in plasma, within the vessel wall and in platelet α-granules. Additional VWF/collagen complexes form as collagen fibrils come into contact with plasma. Circulating erythrocytes facilitate adhesion to collagen by pushing platelets closer to the vessel wall, allowing GP Ibα on the platelet surface to be snared by the VWF A1 domain. Once captured, the drivers for platelet activation include the receptors for collagen (GP VI) and VWF (GP Ibα), thrombin (PAR1 and PAR4), ADP (P2Y1 and P2Y12) and thromboxane A2 (TP) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

An overview of some of the pathways that support platelet activation. Targets for antiplatelet agents that are currently in clinical use or in clinical trials are indicated in blue. PLC, phospholipase C; PKC, protein kinase C; IP3, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate; TxA2, thromboxane A2; GP, glycoprotein; IP and TP, PGI2 and TxA2 receptors

In general terms, agonist-initiated platelet activation begins with the activation of one of the phospholipase C (PLC) isoforms expressed in platelets. By hydrolyzing membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), PLC produces the second messenger inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) needed to raise the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. This leads to integrin activation via a pathway that currently includes a Ca2+-dependent exchange factor (CalDAG-GEF), a switch (Rap1), an adaptor (RIAM), and proteins that interact directly with the integrin cytosolic domains (kindlin and talin) (Shattil et al. 2010). Which PLC isoform is activated depends on the agonist. Collagen activates PLCγ2 using a mechanism that depends on scaffold molecules and protein tyrosine kinases. Thrombin, ADP and TxA2 activate PLCβ using Gq as an intermediary.

The rise in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration that is triggered by most platelet agonists is essential for platelet activation. In resting platelets, the cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration is maintained at approximately 0.1 μM by limiting Ca2+ influx and pumping Ca2+ out of the cytosol either out across the plasma membrane or into the dense tubular system. In activated platelets, the Ca2+ concentration rises tenfold to >1 μM as Ca2+ pours back into the cytosol from two sources. The first is IP3-mediated release of Ca2+ from the platelet dense tubular system (DTS). The second is Ca2+ influx across the platelet plasma membrane, an event triggered when depletion of the DTS Ca2+ pool produces a conformational change in STIM1, a protein located in the DTS membrane. This conformational change promotes the binding of STIM1 to Orai1 in the plasma membrane allowing Ca2+ entry (Varga-Szabo et al. 2011).

Ultimately, it is the binding of fibrinogen or another bivalent ligand to αIIbβ3 that enables platelets to stick to each other. Proteins that can substitute for fibrinogen include fibrin, VWF and fibronectin. Average expression levels of αIIbβ3 range from approximately 50,000 per cell on resting platelets to 80,000 on activated platelets. Mutations in αIIbβ3 that suppress its expression or function produce a bleeding disorder (Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia) because platelets are unable to form stable aggregates. Antiplatelet agents such as Integrilin (eptifibatide) and ReoPro (abciximab) take advantage of this by blocking αIIbβ3.

2 The Early Events of Platelet Activation

Signaling within platelets begins with activation of receptors on the platelet surface by agonists such as collagen, thrombin, ADP, TxA2 and epinephrine. With the exception of collagen, each of these works through one or more members of the G protein coupled receptor superfamily. Some of the properties that are common to G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) make them particularly well-suited for their tasks in platelets. Most bind their ligands with high affinity and each occupied receptor can activate multiple G proteins, amplifying the initial signal. In general, the GPCRs expressed on the platelet surface are present in low copy number, ranging from a few hundred (epinephrine receptors and P2Y1 ADP receptors) to a few thousand (PAR1) copies per cell. Their duration of signaling is subject to receptor internalization, receptor desensitization and the accelerated inactivation of G proteins by members of the RGS (Regulators of G protein Signaling) family. This multiplicity of mechanisms means that platelet activation can be tightly regulated even at its earliest stages.

Although there is now growing evidence in cells other than platelets that GPCRs can signal by more than one mechanism, the events that have been described downstream of the GPCRs in platelets are mediated by heterotrimeric (αβγ) G proteins. Human platelets express ten members of the Gs, Gi, Gq and G12 families. This includes at least one Gs, four Gi (Gi1, Gi2, Gi3 and Gz), three Gq family members (Gq, G11 and G16) and two G12 family members (G12 and G13). As will be discussed below, much has been learned about the role of G proteins in platelets through studies on mice in which the genes encoding one or more forms of Gα have been disrupted.

2.1 Categorizing Critical Events

Faced with the profusion of signaling events underlying platelet activation, it can be helpful to divide them into categories. The first category begins with the activation of PLC, which cleaves membrane PIP2 to produce IP3 and diacylglycerol (DAG), the second messengers needed to raise the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and activate some of the protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms found in platelets. As already noted, collagen activates PLCγ2 using adaptor molecules and tyrosine kinases; thrombin, ADP and TxA2 activate PLCβ using Gq and, perhaps, Gi family members. The subsequent increase in cytosolic Ca2+ triggers downstream events including integrin activation and TxA2 formation.

The second category of critical events involve monomeric G proteins in the Rho and Rac families, whose activation trigger the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton that underlies filopodia and lamellopodia formation. Along with changes in the platelet’s circumferential microtubular ring, filopodia and lamellopodia formation are the essence of platelet shape change. When platelets in suspension are activated by soluble agonists, shape change precedes platelet aggregation. Most platelet agonists can trigger shape change, the notable exception being epinephrine. The soluble agonists (thrombin, ADP and TxA2) that trigger shape change typically act through receptors that are coupled to members of the Gq and G12 family.

The third category of critical events includes the suppression of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) synthesis by adenylyl cyclase, provided the intracellular cAMP concentration has been raised above baseline by the action of endothelium-derived PGI2 and nitric oxide (NO). Inhibition of cAMP formation relieves a block on platelet signaling that otherwise serves to suppress inappropriate platelet activation. The agonists that inhibit cAMP formation in platelets do so by binding to receptors coupled to the Gi family members, especially Gi2 (ADP and thrombin) and Gz (epinephrine). Suppression of adenylyl cyclase is clearly critical when cAMP levels are elevated. It is less clear that it is necessary under basal cAMP conditions.

The fourth category involves activation of the PI 3-kinase isoforms expressed in platelets, either by Gi family members (PI3Kγ) or by phosphotyrosine-dependent signaling pathways downstream of collagen receptors (PI3Kαβδ). PI 3-kinases phosphorylate PI-4-P and PI-4,5-P2 to produce PI-3,4-P2 and PI-3,4,5-P3. Among the best-described consequence of PI3K activation in platelets is the activation of the protein kinase, Akt. Knockout and inhibitor studies demonstrate that all three Akt isoforms are necessary for normal platelet activation (Chen et al. 2004; Woulfe et al. 2004; O’Brien et al. 2011). Knockout and inhibitor studies also show a Gi/PI3K-dependent mechanism for activating Rap1 (Woulfe et al. 2002; Yang et al. 2002) which, given the clinical utility of P2Y12 antagonists as antiplatelet agents, seems to be a mechanism that is important for stabilizing platelet aggregates.

3 G proteins and Their Effectors in Platelets

Platelet agonists are not equally potent. Thrombin provides a robust stimulus for phosphoinositide hydrolysis and causes the largest and fastest increase in cytosolic Ca2+. Collagen and ADP are more dependent on the synthesis and release of TxA2 to achieve a maximal response. In the case of those whose receptors are GPCRs, potency is determined in part by which G proteins their receptors are coupled to, the number of receptor copies, the efficiency with which they activate the G proteins and the susceptibility of any given receptor/G protein pair to signal suppression.

3.1 Gq, Phosphoinositide Hydrolysis, Cytosolic Ca2+ and Integrin Activation

The critical role of Gq in platelets is reflected by the major defect in platelet activation observed in Gqα−/− platelets (Offermanns et al. 1997). As already noted, agonists like thrombin, TxA2 and (to a lesser extent) ADP whose receptors are coupled to Gq provide a strong stimulus for phosphoinositide hydrolysis in platelets by activating PLCβ (Fig. 2). Different isoforms of PLCβ can be activated by either Gα or Gβγ (or both). PLCβ-activating α subunits are typically derived from Gq in platelets, but in theory PLC can also be activated by Gβγ derived from Gi family members. Whether this actually occurs in platelets remains to be demonstrated. In a recent study in which Gi2α was replaced with a gain of function mutant, there was an increase in Gi2-dependent activation of Akt, but no increase in the cytosolic Ca2+ response, which suggests that this mechanism is not a major contributor to PLC activation (Signarvic et al. 2010).

Fig. 2.

Gq signaling in platelets. Agonists whose receptors are coupled to Gq are able to activate PLCβ via Gqα. The potency with which the activation occurs varies with the agonist, with thrombin and TxA2 providing a stronger stimulus for PLCβ-mediated phosphoinositide hydrolysis than ADP. Thrombin activates two Gq-coupled receptors on human platelets, PAR1 and PAR4, which differ somewhat in the kinetics of PLC activation. Abbreviations: AA, arachidonic acid; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; COX-1, cyclooxygenase 1; DAG, diacylglycerol; GDP, guanosine 5′-diphosphate; GTP, guanosine 5′-triphosphate; IP3 R, IP3 receptor; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PAK, p21-activated kinase; PAR, protease-activated receptor; PG, prostaglandin; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate; PKC, protein kinase C; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PLCβ, phospholipase Cβ; TxA2, thromboxane A2

Once initiated, the rising Ca2+ concentration in activated platelets can trigger integrin activation via the CalDAG-GEF/Rap1/RIAM pathway (Lee et al. 2009; Shattil et al. 2010). This pathway accounts for the ability of Ca2+ ionophores to trigger platelet aggregation. Its biological relevance is reflected by the reduction of aggregation in platelets from Rap1 and CalDAG-GEF knockout mice (Crittenden et al. 2004; Chrzanowska-Wodnicka et al. 2005). That the CalDAG-GEF/Rap1/RIAM pathway is not the only way to accomplish integrin activation is reflected by the incomplete reduction of aggregation in Rap1−/− platelets and the ability of PKC activators such as phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) to cause aggregation without causing an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (Shattil and Brass 1987). PKC isoforms phosphorylate multiple cellular proteins on serine and threonine residues. Activation of PKC by PMA is sufficient to cause integrin activation, granule secretion and platelet aggregation in the absence of an increase in cytosolic Ca2+. However, just as the ability of Ca2+ ionophores to activate platelets on their own does not fully account for platelet activation in vivo, neither does the response to PMA.

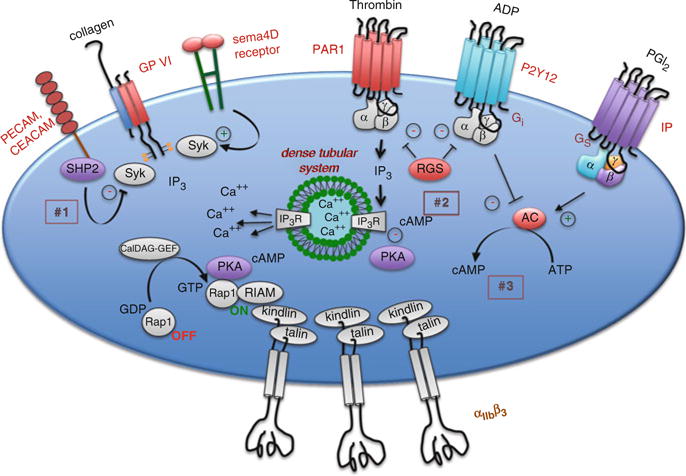

3.2 Gi Family Members, cAMP and PI 3-Kinase

Rising cAMP levels turn off signaling in platelets and an increase in cAMP synthesis is one of the mechanisms by which endothelial cells prevent inappropriate platelet activation. PGI2 and NO released from endothelial cells cause Gsα-mediated increases in adenylyl cyclase activity (PGI2) and inhibit the hydrolysis of cAMP by phosphodiesterases (NO). When added to platelets in vitro, PGI2 can cause a >10-fold increase in the platelet cAMP concentration, but even relatively small increases in cAMP levels (twofold or less) can impair thrombin responses (Keularts et al. 2000). Platelet agonists such as ADP and epinephrine inhibit PGI2-stimulated cAMP synthesis by binding to receptors that are coupled to one or more Gi family members (Fig. 3). Disruption of the genes encoding Gi2α or Gzα causes an increase in the basal cAMP concentration in mouse platelets (Yang et al. 2002). Conversely, loss of PGI2 receptor (IP) expression causes a decrease in basal cAMP levels, enhances responses to agonists and predisposes mice to thrombosis in arterial injury models (Murata et al. 1997; Yang et al. 2002).

Fig. 3.

Gi signaling in platelets. Gi2 is the predominant Gi family member expressed in human platelets. In addition to inhibiting adenylyl cyclase (alleviating the repressive effects of cAMP), Gi2 couples P2Y12 ADP receptors to PI 3-kinase, Akt phosphorylation and Rap1B activation. Other effectors may exist as well. Abbreviations: AC, adenylyl cyclase; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PLA2, phospholipase A2; PLCβ, phospholipase Cβ; GDP, guanosine 5′-diphosphate; GTP, guanosine 5′-triphosphate; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate; PKC, protein kinase C

Although the Gi family members in platelets are most commonly associated with their role in the suppression of cAMP formation, this is not their only role. Neither the defect seen in platelets that are missing Giα family members nor the response to ADP measured in the presence of P2Y12 antagonists (Daniel et al. 1999) can be reversed solely by adding inhibitors of adenylyl cyclase. Other downstream effectors for Gi family members in platelets include PI 3-kinase, Src family members and Rap1B (Dorsam et al. 2002; Lova et al. 2002; Woulfe et al. 2002, 2004). The role of Rap1B in integrin activation was discussed in the context of Gq, Ca2+ and CalDAG-GEF. PI 3-kinases phosphorylate PI-4-P and PI-4,5-P2 to produce PI-3,4-P2 and PI-3,4,5-P3. Human platelets express the α, β, γ and δ isoforms of PI 3-kinase, each of which is composed of a catalytic subunit and a regulatory subunit. The α, β and δ isoforms are activated by binding to phosphorylated tyrosine residues. The PI3Kγ isoform is activated by Gβγ derived from Gi family members.

Much of what is known about the role of PI 3-kinase in platelets comes from studies with inhibitors such as wortmannin and LY294002, or from studies of gene-deleted mouse platelets (Jackson et al. 2004). Those studies have established that PI3K activation can occur downstream of both Gq and Gi family members and that effectors for PI3K in platelets include the serine/threonine kinase, Akt (Woulfe et al. 2004), and Rap1B (Jackson et al. 2005). Loss of the PI3Kγ isoform causes impaired platelet aggregation (Hirsch et al. 2001). Loss of PI3Kβ impairs Rap1B activation and thrombus formation in vivo, as do PI3Kβ-selective inhibitors (Jackson et al. 2005). Most of the Akt expressed in platelets appears to be the Akt2 isoform, but Akt1 and Akt3 (O’Brien et al. 2011) are present as well. All three appear to contribute to platelet activation, at least in mice. Deletion of the gene encoding Akt2 results in impaired thrombus formation and stability, and inhibits secretion (Woulfe et al. 2004). Loss of Akt1 inhibits platelet aggregation (Chen et al. 2004) and affects vascular integrity (Chen et al. 2005). Loss of Akt3 impairs aggregation and secretion (O’Brien et al. 2011).

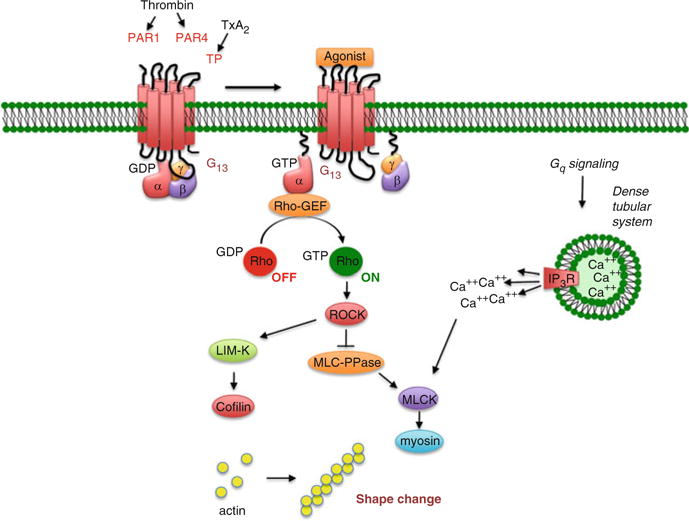

3.3 Gq, G13 and the Reorganization of the Actin Cytoskeleton

At least two effector pathways are involved in the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton that accompanies platelet activation: Ca2+-dependent activation of myosin light chain kinase downstream of Gq family members and activation of Rho family members downstream of G13 (Fig. 4) (Klages et al. 1999; Offermanns 2001). Several proteins having both Gα-interacting domains and guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) domains can link G12 family members to Rho family members, including p115RhoGEF (Fukuhara et al. 2001). With the exception of ADP, shape change persists in platelets from mice that lack Gqα but is lost when G13α expression is suppressed, alone or in combination with G12α (Moers et al. 2003, 2004). These results indicate that for most platelet agonists, G13 signaling is essential for shape change and that the events underlying shape change are invoked by a combination of G13- and Gq-dependent signals. A combination of inhibitor and genetic approaches suggest that G13-dependent Rho activation leads to shape change via pathways that include the Rho-activated kinase (p160ROCK) and LIM-kinase (Klages et al. 1999; Wilde et al. 2000; Pandey et al. 2005). Activation of these kinases results in phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase and cofilin, helping to regulate both actin filament formation and myosin. ADP, on the other hand, depends more heavily on Gq-dependent activation of PLC to produce shape change and is able to activate G13 only as a consequence of TxA2 generation; hence ADP-induced shape change is lost when Gq signaling is suppressed.

Fig. 4.

G12/13 signaling in platelets. Agonists whose receptors are coupled to the G12 family members expressed in platelets are able to trigger shape change, in part by Rho-dependent activation of kinases that include the Rho-activated kinase, p160 ROCK, and the downstream kinases, MLCK and LIM-K. Although G12 and G13 are both expressed, based on knockout studies, G13 is the dominant G12 family member in mouse platelets. Y27632 inhibits p160 ROCK. Abbreviations: GDP, guanosine 5′-diphosphate; GTP, guanosine 5′-triphosphate; IP3 R, receptor for 1,4,5-IP3; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; PAR, protease-activated receptor; TxA2, thromboxane A2

3.4 Phospholipase A2, Arachidonate, COX-1 and TxA2 Production in Platelets

In addition to activating PLC, platelet agonists can activate phospholipase A2 which cleaves membrane phospholipids, liberating arachidonate from the C2 position of the glycerol backbone (Fig. 2). Arachidonate can be transformed into a very large number of bioactive compounds, but TxA2 is the key product in platelets. TxA2 synthesis begins with the cyclooxygenase, COX-1, which forms PGG2 and PGH2 from arachidonate in a two step process that is inhibited by aspirin. PGH2 is then metabolized to TxA2 by thromboxane synthetase. Evidence suggests that phospholipase A2 activation in platelets can occur in more than one way. It can clearly happen in response to an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ as the addition of a Ca2+ ionophore is sufficient to cause phospholipase A2 activation. There is also evidence that MAPK pathway signaling activates phospholipase A2, although not necessarily by direct phosphorylation of phospholipase A2 (Böorsch-Haubold et al. 1995, 1999). Once formed, TxA2 can diffuse out of the platelet, activating nearby receptors in an autocrine or paracrine fashion before it is hydrolyzed to inactive TxB2. Even though TxA2 is a potent platelet activator, its half-life in aqueous solution is limited, which has implications for both its duration of action and its impact downstream from a growing thrombus. Studies on TxA2-induced platelet activation are commonly performed with stable analogs such as U46619.

4 Signaling Responses by Selected Platelet Agonists

4.1 Platelet Activation by Collagen

Four distinct collagen receptors have been identified on human and mouse platelets. Two bind directly to collagen (α2β1 and GP VI); the other two bind to collagen via VWF (αIIbβ3 and GP Ibα) (Fig. 5). Of these, GP VI is the most potent signaling receptor (Clemetson et al. 1999). The structure of the GP VI extracellular domain places it in the immunoglobulin superfamily. Its ability to generate signals rests on its constitutive association with the ITAM-containing Fc receptor γ-chain (FcRγ). Loss of FcRγ affects collagen signaling in part because of loss of a necessary signaling element and in part because FcRγ is required for GP VI to reach the platelet surface. The α2β1 integrin also appears to be necessary for an optimal interaction with collagen, supporting adhesion to collagen and acting as a source of integrin-dependent signaling after engagement (Keely and Parise 1996; Consonni et al. 2012). However, this appears to require an initial wave of signaling that activates α2β1, much as the fibrinogen receptor, αIIbβ3 is activated by signaling within platelets. Human platelets with reduced expression of α2β1 have impaired collagen responses, as do mouse platelets that lack β1 integrins when the ability of these platelets to bind to collagen is tested at high shear (Nieswandt et al. 2001; Kuijpers et al. 2003).

Fig. 5.

Platelet activation by collagen. Platelets use several different molecular complexes to support platelet activation by collagen. These include (1) VWF-mediated binding of collagen to the GPIb-IX-V complex and integrin αIIbβ3, (2) a direct interaction between collagen and both the integrin α2β1 and the GP VI/FcRγ-chain complex. Clustering of GP VI results in the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the FcRγ cytoplasmic domain, followed by the binding and activation of the tyrosine kinase, Syk. One consequence of Syk activation is the phosphorylation and activation of phospholipase Cγ, leading to phosphoinositide hydrolysis, secretion of ADP and the production and release of TxA2

Signaling through GP VI can be studied in isolation with the snake venom protein, convulxin, or with synthetic “collagen-related” peptides (CRP), both of which bind to GP VI, but not to other collagen receptors. According to current models, collagen causes clustering of GP VI. Polymerization of soluble collagen and clustering of GP VI/FcRγ complexes contribute to the lag that is commonly observed when collagen is added to platelets in an aggregometer. This leads to the phosphorylation of FcRγ by Src family tyrosine kinases associated with a proline-rich domain in GP VI (Schmaier et al. 2009). Phosphorylation creates an ITAM motif that is recognized by the tandem SH2 domains of Syk. Association of Syk with the GP VI/FcRγ-chain complex activates Syk and leads to the phosphorylation and activation of PLCγ2. Loss of Syk impairs collagen responses (Poole et al. 1997). PLCγ2 hydrolyzes PIP2, raising the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration and indirectly triggering Ca2+ influx across the platelet plasma membrane. The changes in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration that occur when platelets adhere to collagen under flow can be visualized in real time (Nesbitt et al. 2003; Kulkarni et al. 2004).

4.2 Platelet Activation by ADP

ADP is stored in platelet dense granules and released upon platelet activation. It is also released from damaged cells at sites of vascular injury, serving as an autocrine and paracrine stimulus for recruiting additional platelets and stabilizing the hemostatic plug. Aggregation studies performed ex vivo show that all of the other platelet agonists are dependent to some extent on released ADP to elicit maximal platelet aggregation, although this dependence varies with the agonist and is dose-related. When added to platelets in vitro, ADP causes TxA2 formation, protein phosphorylation, an increase in cytosolic Ca2+, shape change, aggregation and secretion. It also inhibits cAMP formation. These responses are half-maximal at approximately 1 μM ADP. However, even at high concentrations, ADP is a comparatively weak activator of PLC, its utility as a platelet agonist resting more upon its ability to activate other pathways. Human and mouse platelets express two distinct GPCRs for ADP, denoted P2Y1 and P2Y12. P2Y1 receptors couple to Gq. P2Y12 receptors couple to Gi family members other than Gz. Optimal activation of platelets by ADP requires activation of both receptors. When P2Y1 is blocked or deleted, ADP is still able to inhibit cAMP formation, but its ability to cause an increase in cytosolic Ca2+, shape change and aggregation is greatly impaired, as it is in platelets from mice that lack Gqα (Offermanns et al. 1997). P2Y1−/− mice have a minimal increase in bleeding time and show some resistance to thromboembolic mortality following injection of ADP, but no predisposition to spontaneous hemorrhage. Primary responses to platelet agonists other than ADP are unaffected and when combined with serotonin, which is a weak stimulus for PLC in platelets, ADP can still cause aggregation of P2Y1−/− platelets. Taken together, these results show that platelet P2Y1 receptors are coupled to Gqα and responsible for activation of PLC. P2Y1 receptors can also activate Rac and the Rac effector, p21-activated kinase (PAK), but do not appear to be coupled to Gi family members.

As had been predicted by inhibitor studies and by the phenotype of a patient lacking functional P2Y12, platelets from P2Y12−/− mice do not aggregate normally in response to ADP (Foster 2001). P2Y12−/− platelets retain P2Y1-associated responses, including shape change and PLC activation, but lack the ability to inhibit cAMP formation in response to ADP. The Gi family member associated with P2Y12 appears to be primarily Gi2, since platelets from Gi2α−/− mice have an impaired response to ADP (Jantzen et al. 2001; Yang et al. 2002), while those lacking Gi3α or Gzα do not (Yang et al. 2000, 2002). Conversely, expression of a Gi2α variant that is resistant to the inhibitory effects of RGS proteins produces a gain of function in mouse platelets stimulated with ADP (Signarvic et al. 2010).

4.3 Platelet Activation by Thrombin

Platelet responses to thrombin are mediated by members of the protease-activated receptor (PAR) family of GPCRs. There are four members of this family, three of which (PAR1, PAR3 and PAR4) can be activated by thrombin. PAR1 and PAR4 are expressed on human platelets; mouse platelets express PAR3 and PAR4. Receptor activation occurs when thrombin cleaves the extended N-terminus of each of these receptors, exposing a new N-terminus that serves as a tethered ligand (Vu et al. 1991). Synthetic peptides based on the sequence of the tethered ligand domain of PAR1 and PAR4 are able to activate the receptors, mimicking at least some of the actions of thrombin. While human PAR3 has been shown to signal in response to thrombin in transfected cells, PAR3 on mouse platelets appears to primarily serve to facilitate cleavage of PAR4 rather than to generate signals on its own (Nakanishi-Matsui et al. 2000).

Thrombin is able to activate platelets at concentrations as low as 0.1 nM. Although other platelet agonists can also cause phosphoinositide hydrolysis, none appear to be as efficiently coupled to phospholipase C as thrombin. Within seconds of the addition of thrombin, the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration increases tenfold, triggering downstream Ca2+-dependent events, including the activation of phospholipase A2. Thrombin also activates Rho, leading to rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton and shape change, responses that are greatly reduced or absent in mouse platelets that lack G13α. Finally, thrombin is able to inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity in human platelets, either directly (via a Gi family member) or indirectly (via released ADP) (Barr et al. 1997; Kim et al. 2000).

4.4 Platelet Activation by Epinephrine

Compared to thrombin, epinephrine is a weak activator of human platelets. Nonetheless, there are reports of human families in which a mild bleeding disorder is associated with impaired epinephrine-induced aggregation and reduced numbers of catecholamine receptors. Epinephrine responses in platelets are mediated by α2A-adrenergic receptors (Kaywin et al. 1978; Newman et al. 1978; Motulsky and Insel 1982). In both mice and humans, epinephrine is able to potentiate the effects of other agonists. Potentiation is usually attributed to the ability of epinephrine to inhibit cAMP formation, but there are clearly other effects as well. Epinephrine has no detectable direct effect on phospholipase C and does not cause shape change, although it can trigger phosphoinositide hydrolysis indirectly by stimulating TxA2 formation. These results suggest that platelet α2A-adrenergic receptors are coupled to Gi family members, but not Gq or G12 family members. Knockout studies show that epinephrine responses in mouse platelets are abolished when Gzα expression is abolished, while loss of Gi2α or Gi3α has no effect. Gz also appears to be responsible for the ability of epinephrine to activate Rap1B (Woulfe et al. 2002; Yang et al. 2002).

4.5 Platelet Activation by TxA2

When added to platelets in vitro, stable thromboxane analogs such as U46619 cause shape change, aggregation, secretion, phosphoinositide hydrolysis, protein phosphorylation and an increase in cytosolic Ca2+, while having little if any direct effect on cAMP formation. Similar responses are seen when platelets are incubated with exogenous arachidonate (Gerrard and Carroll 1981). Once formed, TxA2 can diffuse across the plasma membrane and activate other platelets (Fig. 1) (FitzGerald 1991). Like secreted ADP, release of TxA2 amplifies the initial stimulus for platelet activation and helps to recruit additional platelets. This process is limited by the brief half-life of TxA2 in solution, helping to confine the spread of platelet activation to the original area of injury. Loss of Gqα abolishes U46619-induced IP3 formation and changes in cytosolic Ca2+, but does not prevent shape change (Offermanns et al. 1997). Loss of G13α abolishes TxA2-induced shape change (Moers et al. 2003). In cells other than platelets, TPα and TPβ have been shown to couple to Gi family members (Gao et al. 2001), however, in platelets the inhibitory effects of U46619 on cAMP formation appear to be mediated by secreted ADP. These observations have previously been interpreted to mean that platelet TxA2 receptors are coupled to Gq and G12/13, but not to Gi family members. However, the gain of function recently observed in mouse platelets carrying an RGS protein resistant Gi2α variant suggests that this is still an open issue (Signarvic et al. 2010). TP−/− mice have a prolonged bleeding time. Their platelets are unable to aggregate in response to TxA2 agonists and show delayed aggregation with collagen, presumably reflecting the role of TxA2 in platelet responses to collagen (Thomas et al. 1998). The most compelling case for the contribution of TxA2 signaling in human platelets comes from the successful use of aspirin as an antiplatelet agent. When added to platelets in vitro, aspirin abolishes TxA2 generation (Fig. 1). It also blocks platelet activation by arachidonate and impairs responses to thrombin and ADP. The defect in thrombin responses appears as a shift in the dose/response curve, indicating that TxA2 generation is supportive of platelet activation by thrombin, but not essential.

5 Some of the Later Events in Platelet Activation

As platelet activation in response to injury proceeds in vivo, previously mobile platelets come into increasingly stable contact with each other, eventually with sufficient stability and proximity that molecules on the surface of one platelet can interact directly with molecules on the surface of adjacent platelets. Although in theory this can occur anywhere within a growing hemostatic plug or thrombus, it is likely to occur most readily in the thrombus core where platelets appear to be closest together. Stable cohesive contacts between platelets require engagement of αIIbβ3 with one of its ligands, after which inward-directed (i.e., outside-in) signaling occurs through the integrin and through other molecules that can then engage with their counterparts in trans. Some of these are primarily signal-generating events that affect platelet activation and thrombus stability. Others serve primarily to help form contacts between platelets and create a protected space in which soluble molecules, including agonists, can accumulate.

5.1 Outside-In Signaling by Integrins

Activated αIIbβ3 bound to fibrinogen, fibrin or VWF provides the dominant cohesive strength that holds platelet aggregates together. It also contributes a further impetus for sustained platelet activation by serving as a scaffold for the assembly of signaling molecules (Prevost et al. 2007; Shattil 2009; Stegner and Nieswandt 2011). The term “outside-in signaling” refers to the effects of these molecules (Shattil and Newman 2004). Some of the protein–protein interactions that involve the cytoplasmic domains of αIIbβ3 help regulate integrin activation; others participate in outside-in signaling and clot retraction. Proteins that are capable of binding directly to the cytoplasmic domains of αIIbβ3 include β3-endonexin, CIB1, talin, kindlin, myosin, Shc and the tyrosine kinases, Src, Fyn and Syk. Some interactions require the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues Y773 and Y785 in the β3 cytoplasmic domain by Src family members. Mutation of the corresponding tyrosine residues in mice produces platelets with impaired clot retraction and a tendency to re-bleed from tail bleeding time sites (Law et al. 1999a). Fibrinogen binding to the extracellular domain of activated αIIbβ3 stimulates an increase in the activity of Src family kinases and Syk (Law et al. 1999a, b). Studies of platelets from mice lacking these kinases suggest that these events are required for the initiation of outside-in signaling and for full platelet spreading, irreversible aggregation and clot retraction. There is also evidence that the ITAM-containing receptor, FcγRIIa, is the link between Src family kinase and Syk activation in human platelets activated by αIIbβ3 (Boylan et al. 2008).

5.2 Cell Surface Ligands and Receptors

The close proximity of one platelet to another can permit the direct binding of cell surface ligands to cell surface receptors on adjacent platelets. Several examples have been identified in platelets, including members of the ephrins and semaphorin families plus their respective receptors (Eph kinases and plexins). Ephrins are cell surface molecules attached by either a GPI anchor (ephrin A family members) or a single transmembrane domain (ephrin B family members). Eph kinases have a single transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic domain that includes the catalytic domain and protein:protein interaction motifs. Human platelets express EphA4 and EphB1 plus their ligand, ephrinB1 (Prevost et al. 2002). Forced clustering of either EphA4 or ephrinB1 results in cytoskeletal changes leading to platelet spreading, as well as to increased adhesion to fibrinogen, Rap1B activation and granule secretion (Prevost et al. 2002, 2004). EphA4 associates with αIIbβ3 and Eph/ephrin interactions promote phosphorylation of the β3 cytoplasmic domain. Conversely, blockade of Eph/ephrin interactions impairs clot retraction and causes platelet disaggregation at low agonist concentrations, resulting in impaired thrombus growth. It also inhibits platelet accumulation on collagen under flow (Prevost et al. 2002, 2005).

Semaphorin 4D (Sema4D, CD100) provides another example of a cell surface ligand involved in contact-dependent signaling in platelets. Like the ephrins, semaphorins are best known for their role in the developing nervous system, but they have also been implicated in organogenesis, vascularization and immune cell regulation. Semaphorins can either be secreted, bound to the plasma membrane via a transmembrane domain or held in place with a GPI anchor. Sema4D, which has a transmembrane domain, is expressed on the surface of both mouse and human platelets and is slowly shed from the surface of activated platelets by the metalloprotease, ADAM17 (Zhu et al. 2007). Human platelets express at least two receptors for sema4D: CD72 and a member of the plexin B family (Zhu et al. 2007). Mouse platelets express the plexin, but not CD72. Sema4D−/− mouse platelets have a defect in their responses to collagen and convulxin in vitro, and a reduced response to vascular injury in vivo (Zhu et al. 2007). Responses to thrombin, ADP and TxA2 mimetics are normal. The collagen defect has been mapped to a failure to maximally activate Syk downstream of the collagen receptor, GP VI. Events in the pathway upstream of Syk occur normally in sema4D−/− platelets (Zhu et al. 2007; Wannemacher et al. 2010). Notably, these defects are observed only when platelets come in contact with each other and can be reversed by adding soluble recombinant sema4D. Thus, the evidence suggests that sema4D provides a contact-dependent boost in collagen-signaling. The platelets which are most likely to be activated via GP VI are those in the initial monolayer that accumulates on exposed collagen.

6 Regulators of Platelet Activation

The molecular mechanisms that drive platelet activation reflect an evolutionary compromise necessitated in part by the switch from nucleated thrombocytes to the more complex system of stationary megakaryocytes and circulating platelets found in mammals. This compromise can be thought of as establishing a threshold for platelet activation. If the threshold is too high, then platelets become useless for hemostasis. If too low, then the risk for unwarranted platelet activation rises. The set point normally found in humans and other mammals is established by balancing the intracellular signaling mechanisms that drive platelet activation forward in response to injury with regulatory mechanisms that either dampen those responses or prevent their initiation in the first place.

Regulatory events that impact platelet reactivity can be viewed as being extrinsic and intrinsic. A healthy endothelial monolayer provides a physical barrier that limits platelet activation. It also produces inhibitors of platelet activation including NO, prostacyclin (PGI2) and the surface ecto-ADPase, CD39, which hydrolyzes plasma ADP that would otherwise sensitize platelets to activation by other agonists. In addition to these extrinsic regulators of platelet function, a number of intrinsic regulators of platelet activation have been identified. A few of them will be considered briefly here, including those that limit G protein-dependent signaling and those that impact platelet activation by collagen (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Regulatory events that impact platelet activation. Although platelets are primed to respond rapidly to injury, a number of regulatory events have been described that can limit the rate and/or extent of the response. Examples shown in the figure include (1) PECAM and CEACAM, which reduce Syk activation downstream of the collagen receptor, GP VI, by recruiting the tyrosine phosphatase, SHP2, (2) RGS10 and RGS18 which shorten the duration of G protein-dependent signaling in platelets and (3) PGI2, which stimulates cAMP formation in platelets and dampens platelet responsiveness via protein kinase A (PKA)

6.1 Regulation of G Protein-Dependent Signaling

As already noted, most of the agonists which extend the platelet plug do so via G protein coupled receptors. The properties of these receptors make them particularly well-suited for this task. Because mechanisms exist that can limit the activation of G protein coupled receptors, platelet activation can be tightly regulated even at its earliest stages. Based largely on work in cells other than platelets, those regulatory mechanisms likely include receptor internalization, receptor phosphorylation, the binding of cytoplasmic molecules such as arrestin family members and the limits on signal duration imposed by RGS (Regulator of G protein Signaling) proteins. The role of RGS proteins in platelets is just beginning to be defined. In cells other than platelets, RGS proteins limit signaling intensity and duration by accelerating the hydrolysis of GTP by activated G protein α subunits. At least 10 RGS proteins have been identified in platelets at the RNA level, but only RGS10 and RGS18 have been confirmed at the protein level. The evidence that RGS proteins are biologically relevant in platelets comes from studies on mice in which glycine 184 in the α subunit of Gi2 has been replaced with serine, rendering it unable to interact with RGS proteins without impairing the ability of Gi2 to interact with either receptors or downstream effectors. This substitution produces the predicted gain of platelet function in vitro and in vivo, even in the heterozygous state (Signarvic et al. 2010).

6.2 cAMP and Protein Kinase A

The best-known inhibitor of platelet activation is cAMP. As already noted, rising cAMP levels turn off signaling in platelets. Regulatory molecules released from endothelial cells cause Gsα-mediated increases in adenylyl cyclase activity (PGI2) and inhibit the hydrolysis of cAMP by phosphodiesterases (NO). Deletion of the genes encoding either Gi2α or Gzα causes an increase in the basal cAMP concentration in mouse platelets (Yang et al. 2002). cAMP phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as dipyridamole act as anti-platelet agents by raising cAMP levels. Conversely, loss of PGI2 receptor (IP) expression in mice causes a decrease in basal cAMP levels, enhances responses to agonists, and predisposes mice to thrombosis in arterial injury models (Murata et al. 1997; Yang et al. 2002). Despite ample evidence that cAMP inhibits platelet activation, the mechanisms by which it does this are not fully defined. cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) is thought to be essential, but other mechanisms may be involved as well. Numerous substrates for the kinase have been described, including some G protein coupled receptors, IP3 receptors, GP Ibβ, vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) and Rap1, but it is still not clear whether a single substrate accounts for most of the effect or whether it is the accumulated effect of phosphorylation of many substrates.

6.3 Adhesion/Junction Receptors Contribute to Contact-Dependent Signaling

In addition to amplifying platelet activation, contact-dependent signaling can also help to limit thrombus growth and stability. Examples of this phenomenon include, PECAM-1, CEACAM1 and members of the CTX family of adhesion molecules. Knockouts of any of these in mice produce a gain of function, rather than a loss of function phenotype. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) is a type-1 transmembrane protein with six extracellular domains, the most distal of which can form homophilic interactions in trans (Newman and Newman 2003). The cytoplasmic domain contains two immunoreceptor tyrosine inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) that can bind the tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-2 (Jackson et al. 1997). PECAM1-deficient platelets exhibit enhanced responses to collagen in vitro and in vivo, consistent with a model in which PECAM-1 localizes SHP-2 to its substrates, including the GP VI signaling complex, thus providing a brake and preventing excessive platelet activation and thrombus growth (Patil et al. 2001; Falati et al. 2006; Moraes et al. 2010).

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) is a second ITIM family member expressed on the platelet surface that can form homophilic and heterophilic interactions with other CEACAM superfamily members. In contrast to PECAM-1, the CEACAM1 ITIMs prefer SHP-1 over SHP-2, although either can become bound. The CEACAM1 knockout, like the PECAM-1 knockout produces a gain of function, showing increased platelet activation in vitro in response to collagen and increased thrombus formation in a FeCl3 injury model (Wong et al. 2009). Thus, at least on the basis of the knockout results, CEACAM1 also appears to be a negative regulator of GP VI signaling.

7 Concluding Thoughts

This chapter represents our collective effort to summarize the efforts of a small, but passionate community of investigators who have worked to understand the molecular basis for platelet activation in vivo. In writing the chapter, we have focused on pathways, but have attempted to place those pathways in the context of observable events. The subject of platelet activation remains a work in progress and we have tried to incorporate perspectives that have been gained recently. We would like to close by pointing out some of the blank places on the platelet signaling map and by briefly reflecting on what might be coming next.

One of the biggest advances in the platelet field over the past 10 years has come from studies on how platelets are made. The process of proplatelet formation is described elsewhere in this volume. From the perspective of signal transduction and platelet response mechanisms, there are large unanswered questions about how a developing platelet at the tip of a proplatelet extension becomes equipped with the necessary molecular toolkit to not only drive a response to injury, but also to regulate that response to make it safe. Might some platelets be endowed with greater adhesive capabilities and be best at forming the initial monolayer on exposed collagen fibrils? Might others be particularly well suited for cohesive (platelet:platelet) interactions, either because of their complement of integrins or their density of receptors for soluble agonists such as ADP, thrombin and TxA2? Heterogeneity among platelet populations within a single individual could easily extend to heterogeneity among individuals, perhaps contributing to risks for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular compromise (Bray 2007; Bray et al. 2007a, b; Watkins et al. 2009; Johnson et al. 2010; Kunicki and Nugent 2010; Musunuru et al. 2010). Finally, platelets contain a broad representation of megakaryocyte RNA (Rowley et al. 2011), although not all of the proteins present in platelets are accompanied by the corresponding message (Cecchetti et al. 2011). Platelets also express the synthetic machinery needed to produce proteins (Weyrich et al. 1998; Denis et al. 2005; Schwertz et al. 2012). How do the changes that occur when platelets age in the circulation affect platelet function and how might the protein synthetic capability within the platelets help to withstand those changes or reconfigure the platelet during the hemostatic response?

A second source of recent energy in the platelet community has been the identification of new roles for platelets beyond those associated with the hemostatic response to injury. These include roles in embryonic development, innate immunity and oncogenesis. How do each of these roles draw on the molecular toolkit for platelet activation? Although the full answer to that question is not yet known, there appears to be only a partial overlap. Thus, for example, the separation of lymphatics from the vasculature depends in part on signaling pathways that are identical to those that drive platelet responses to collagen downstream of GP VI. However, instead of GP VI, the initiation of those signaling events involves a separate receptor, CLEC-2 (Hughes et al. 2010; Suzuki-Inoue et al. 2010). Similarly, platelet involvement in innate immunity appears to be driven in part by TLRs (Toll like receptors), molecules that have not appeared elsewhere in this chapter, but which are receiving increased attention for their role in platelets (Semple et al. 2011).

Knowledge Gaps.

Although many of the critical signaling pathways in platelets have been mapped, uncertainties remain about the complete mechanisms for activating αIIbβ3 and causing granule exocytosis.

Gaps also remain in understanding how platelet activation is regulated so that an optimal response to local injury can be achieved without excessive accumulation of platelets.

Platelets are generally treated as if they are all the same in each individual. However, it is not yet clear whether there are meaningful differences among platelets that optimize their ability to perform specific functions.

Conversely, except in cases of well-defined monogenic disorders, it is not yet clear whether the differences observed in platelet aggregation among different individual donors necessarily have a definable molecular basis and a meaningful clinical impact.

Finally, this chapter focuses on the hemostatic response to vascular injury. Uncertainty remains about the activation mechanisms that underlie pathological platelet activation. Some of them are undoubtedly the same as those employed in the hemostatic response. Others are proving not to be.

Key Messages.

Platelet activation during the response to vascular injury is a tightly coordinated process in which platelets are exposed to multiple activators and inhibitors, producing a response that is the net effect of all of these inputs.

The most commonly encountered (and best understood) platelet agonists in vivo are thrombin, collagen, ADP, TxA2 and epinephrine. With the exception of collagen, each of these agonists activates one or more G protein coupled receptor and signals through one or more classes of heterotrimeric G proteins. Many of these receptors have proved to prime targets for antiplatelet drugs, including the P2Y12 and PAR1 antagonists as well as aspirin, which inhibits TxA2 formation in platelets.

Signal transduction during platelet activation is typically described one agonist and one pathway at a time, but it is in reality a signaling network in which different pathways can reinforce or oppose each other. Each pathway is also subject to the restraining effects of one or more inhibitors, including cAMP, RGS proteins and protein phosphatases, not all of which are fully understood.

Once platelets are turned on, intracellular signaling that depends on a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ triggers a conformational change in the extracellular domain of αIIbβ3 (GP IIb–IIIa), exposing the fibrinogen (and fibrin) binding site on the integrin and allowing it mediate platelet aggregation.

The development of integrin-mediated contacts between platelets makes possible a secondary wave of contact-dependent signaling that amplifies platelet accumulation and promotes formation of a stable thrombus.

Platelet aggregation also promotes granule secretion and the release of molecules into the local surroundings that support the recruitment of additional platelets, but can also affect angiogenesis, the recruitment of leukocytes and wound healing.

Contributor Information

Timothy J. Stalker, Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Debra K. Newman, The BloodCenter of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA

Peisong Ma, Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Kenneth M. Wannemacher, Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Lawrence F. Brass, Email: brass@mail.med.upenn.edu, Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

References

- Barr AJ, Brass LF, Manning DR. Reconstitution of receptors and GTP-binding regulatory proteins (G proteins) in Sf9 cells: a direct evaluation of selectivity in receptor-G protein coupling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2223–2229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellido-Martin L, Chen V, Jasuja R, Furie B, Furie BC. Imaging fibrin formation and platelet and endothelial cell activation in vivo. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:776–782. doi: 10.1160/TH10-12-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Haubold AG, Kramer RM, Watson SP. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is phosphorylated in collagen- and thrombin-stimulated human platelets independent of protein kinase C and mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25885–25892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Haubold AG, Ghomashchi F, Pasquet S, Goedert M, Cohen P, Gelb MH, Watson SP. Phosphorylation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in platelets is mediated by multiple stress-activated protein kinase pathways. Eur J Biochem. 1999;265:195–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan B, Gao C, Rathore V, Gill JC, Newman DK, Newman PJ. Identification of FcgammaRIIa as the ITAM-bearing receptor mediating alphaIIbbeta3 outside-in integrin signaling in human platelets. Blood. 2008;112:2780–2786. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-142125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brass LF, Wannemacher KM, Ma P, Stalker TJ. Regulating thrombus growth and stability to achieve an optimal response to injury. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(Suppl 1):66–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray PF. Platelet hyperreactivity: predictive and intrinsic properties. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007;21:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2007.06.002. doi:S0889-8588(07)00071-8 [pii] 10.1016/j.hoc.2007.06.002, v–vi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray PF, Howard TD, Vittinghoff E, Sane DC, Herrington DM. Effect of genetic variations in platelet glycoproteins Ibalpha and VI on the risk for coronary heart disease events in postmenopausal women taking hormone therapy. Blood. 2007a;109:1862–1869. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013151. doi:blood-2006-03-013151 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray PF, Mathias RA, Faraday N, et al. Heritability of platelet function in families with premature coronary artery disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2007b;5:1617–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02618.x. doi:JTH02618 [pii] 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti L, Tolley ND, Michetti N, Bury L, Weyrich AS, Gresele P. Megakaryocytes differentially sort mRNAs for matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors into platelets: a mechanism for regulating synthetic events. Blood. 2011;118:1903–1911. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, De S, Damron DS, Chen WS, Hay N, Byzova TV. Impaired platelet responses to thrombin and collagen in AKT-1-deficient mice. Blood. 2004;104:1703–1710. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Somanath PR, Razorenova O, Chen WS, Hay N, Bornstein P, Byzova TV. Akt1 regulates pathological angiogenesis, vascular maturation and permeability in vivo. Nat Med. 2005;11:1188–1196. doi: 10.1038/nm1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Smyth SS, Schoenwaelder SM, Fischer TH, White GC., 2nd Rap1b is required for normal platelet function and hemostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:680–687. doi: 10.1172/JCI22973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemetson JM, Polgar J, Magnenat E, Wells TNC, Clemetson KJ. The platelet collagen receptor glycoprotein VI is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily closely related to FcalphaR and the natural killer receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29019–29024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consonni A, Cipolla L, Guidetti G, et al. Role and regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase beta in platelet integrin alpha2beta1 signaling. Blood. 2012;119:847–856. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-364992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden JR, Bergmeier W, Zhang Y, et al. CalDAG-GEFI integrates signaling for platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. Nat Med. 2004;10:982–986. doi: 10.1038/nm1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel JL, Dangelmaier C, Jin JG, Kim YB, Kunapuli SP. Role of intracellular signaling events in ADP-induced platelet aggregation. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1322–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis MM, Tolley ND, Bunting M, et al. Escaping the nuclear confines: signal-dependent pre-mRNA splicing in anucleate platelets. Cell. 2005;122:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsam RT, Kim S, Jin JG, Kunapuli SP. Coordinated signaling through both G12/13 and Gi pathways is sufficient to activate GPIIb/IIIa in human platelets. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17948–17941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falati S, Patil S, Gross PL, et al. Platelet PECAM-1 inhibits thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2006;107:535–541. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1512. doi:2005-04-1512 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald GA. Mechanisms of platelet activation: thromboxane A2 as an amplifying signal for other agonists. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:11B–15B. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90379-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster CJ. Molecular identification and characterization of the platelet ADP receptor targeted by thienopyridine drugs using P2Yac-null mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1591–1598. doi: 10.1172/JCI12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara S, Chikumi H, Gutkind JS. RGS-containing RhoGEFs: the missing link between transforming G proteins and Rho? Oncogene. 2001;20:1661–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Tang S, Zhou S, Ware JA. The thromboxane A2 receptor activates mitogen-activated protein kinase via protein kinase C-dependent Gi coupling and Src-dependent phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:426–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard JM, Carroll RC. Stimulation of protein phosphorylation by arachidonic acid and endoperoxide analog. Prostaglandins. 1981;22:81–94. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(81)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Bosco O, Tropel P, et al. Resistance to thromboembolism in PI3Kgamma-deficient mice. FASEB J. 2001;15:NIL307–NIL326. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0810fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CE, Navarro-Nunez L, Finney BA, Mourao-Sa D, Pollitt AY, Watson SP. CLEC-2 is not required for platelet aggregation at arteriolar shear. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2328–2332. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DE, Kupcho KR, Newman PJ. Characterization of phosphotyrosine binding motifs in the cytoplasmic domain of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) that are required for the cellular association and activation of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24868–24875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Yap CL, Anderson KE. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases and the regulation of platelet function. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:387–392. doi: 10.1042/bst0320387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Schoenwaelder SM, Goncalves I, et al. PI 3-kinase p110beta: a new target for antithrombotic therapy. Nat Med. 2005;11:507–514. doi: 10.1038/nm1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantzen H-M, Milstone DS, Gousset L, Conley PB, Mortensen RM. Impaired activation of murine platelets lacking Galphai2. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:477–483. doi: 10.1172/JCI12818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AD, Yanek LR, Chen MH, et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses identifies seven loci associated with platelet aggregation in response to agonists. Nat Genet. 2010;42:608–613. doi: 10.1038/ng.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaywin P, McDonough M, Insel PA, Shattil SJ. Platelet function in essential thrombocythemia: decreased epinephrine responsivenesss associated with a deficiency of platelet alpha-adrenergic receptors. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:505–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197809072991002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keely PJ, Parise LV. The alpha2beta1 integrin is a necessary co-receptor for collagen-induced activation of Syk and the subsequent phosphorylation of phospholipase Cgamma2 in platelets. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26668–26676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keularts IMLW, Van Gorp RMA, Feijge MAH, Vuist WMJ, Heemskerk JWM. alpha2A-adrenergic receptor stimulation potentiates calcium release in platelets by modulating cAMP levels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1763–1772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Quinton TM, Cattaneo M, Kunapuli SP. Evidence for diverse signal transduction pathways in thrombin receptor activating peptide (SFLLRN) and other agonist-induced fibrinogen receptor activation in human platelets. Blood. 2000;96:242a–240. [Google Scholar]

- Klages B, Brandt U, Simon MI, Schultz G, Offermanns S. Activation of G12/G13 results in shape change and Rho/Rho-kinase-mediated myosin light chain phosphorylation in mouse platelets. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:745–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers MJ, Schulte V, Bergmeier W, et al. Complementary roles of glycoprotein VI and alpha2beta1 integrin in collagen-induced thrombus formation in flowing whole blood ex vivo. FASEB J. 2003;17:685–687. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0381fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni S, Nesbitt WS, Dopheide SM, Hughan SC, Harper IS, Jackson SP. Techniques to examine platelet adhesive interactions under flow. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;272:165–186. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-782-3:165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunicki TJ, Nugent DJ. The genetics of normal platelet reactivity. Blood. 2010;116:2627–2634. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-262048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law DA, DeGuzman FR, Heiser P, Ministri-Madrid K, Killeen N, Phillips DR. Integrin cytoplasmic tyrosine motif is required for outside-in alphaIIbbeta3 signalling and platelet function. Nature. 1999a;401:808–811. doi: 10.1038/44599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law DA, Nannizzi-Alaimo L, Ministri K, et al. Genetic and pharmacological analyses of Syk function in alphaIIbbeta3 signaling in platelets. Blood. 1999b;93:2645–2652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Lim CJ, Puzon-McLaughlin W, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. RIAM activates integrins by linking talin to ras GTPase membrane-targeting sequences. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:5119–5127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807117200. doi:M807117200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M807117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lova P, Paganini S, Sinigaglia F, Balduini C, Torti M. A Gi-dependent pathway is required for activation of the small GTPase Rap1B in human platelets. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12009–12015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moers A, Nieswandt B, Massberg S, et al. G13 is an essential mediator of platelet activation in hemostasis and thrombosis. Nat Med. 2003;9:1418–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moers A, Wettschureck N, Gruner S, Nieswandt B, Offermanns S. Unresponsiveness of platelets lacking both Galpha(q) and Galpha(13). Implications for collagen-induced platelet activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45354–45359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes LA, Barrett NE, Jones CI, et al. PECAM-1 regulates collagen-stimulated platelet function by modulating the association of PI3 Kinase with Gab1 and LAT. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2530–2541. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04025.x. doi:JTH4025 [pii] 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky HJ, Insel PA. [3 H]Dihydroergocryptine binding to alpha-adrenergic receptors of human platelets. A reassessment using the selective radioligands [3 H]prazosin, [3 H]yohimbine, and [3 H]rauwolscine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1982;31:2591–2597. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(82)90705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T, Ushikubi F, Matsuoka T, et al. Altered pain perception and inflammatory response in mice lacking prostacyclin receptor. Nature. 1997;388:678–682. doi: 10.1038/41780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musunuru K, Post WS, Herzog W, et al. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms on chromosome 9p21.3 with platelet reactivity: a potential mechanism for increased vascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:445–453. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.923508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi-Matsui M, Zheng YW, Sulciner DJ, Weiss EJ, Ludeman MJ, Coughlin SR. PAR3 is a cofactor for PAR4 activation by thrombin. Nature. 2000;404:609–610. doi: 10.1038/35007085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt WS, Giuliano S, Kulkarni S, Dopheide SM, Harper IS, Jackson SP. Intercellular calcium communication regulates platelet aggregation and thrombus growth. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:1151–1161. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt WS, Westein E, Tovar-Lopez FJ, et al. A shear gradient-dependent platelet aggregation mechanism drives thrombus formation. Nat Med. 2009;15:665–673. doi: 10.1038/nm.1955. doi:nm.1955 [pii] 10.1038/nm.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman PJ, Newman DK. Signal transduction pathways mediated by PECAM-1: new roles for an old molecule in platelet and vascular cell biology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:953–964. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000071347.69358.D9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman KD, Williams LT, Bishopric NH, Lefkowitz RJ. Identification of alpha-adrenergic receptors in human platelets by 3 H-dihydroergocryptine binding. J Clin Invest. 1978;61:395–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI108950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieswandt B, Brakebusch C, Bergmeier W, et al. Glycoprotein VI but not alpha2beta1 integrin is essential for platelet interaction with collagen. EMBO J. 2001;20:2120–2130. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.9.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KA, Stojanovic-Terpo A, Hay N, Du X. An important role for Akt3 in platelet activation and thrombosis. Blood. 2011;118:4215–4223. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-323204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offermanns S. In vivo functions of heterotrimeric G-proteins: studies in Galpha-deficient mice. Oncogene. 2001;20:1635–1642. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offermanns S, Toombs CF, Hu YH, Simon MI. Defective platelet activation in Galphaq-deficient mice. Nature. 1997;389:183–186. doi: 10.1038/38284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey D, Goyal P, Bamburg JR, Siess W. Regulation of LIM-kinase 1 and cofilin in thrombin-stimulated platelets. Blood. 2005;107:575–583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S, Newman DK, Newman PJ. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 serves as an inhibitory receptor that modulates platelet responses to collagen. Blood. 2001;97:1727–1732. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole A, Gibbins JM, Turner M, et al. The Fc receptor gamma-chain and the tyrosine kinase Syk are essential for activation of mouse platelets by collagen. EMBO J. 1997;16:2333–2341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost N, Woulfe D, Tanaka T, Brass LF. Interactions between Eph kinases and ephrins provide a mechanism to support platelet aggregation once cell-to-cell contact has occurred. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9219–9224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142053899. doi:10.1073/pnas.142053899 142053899 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost N, Woulfe DS, Tognolini M, et al. Signaling by ephrinB1 and Eph kinases in platelets promotes Rap1 activation, platelet adhesion, and aggregation via effector pathways that do not require phosphorylation of ephrinB1. Blood. 2004;103:1348–1355. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost N, Woulfe DS, Jiang H, Stalker TJ, Marchese P, Ruggeri ZM, Brass LF. Eph kinases and ephrins support thrombus growth and stability by regulating integrin outside-in signaling in platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9820–9825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404065102. doi:0404065102 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0404065102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost N, Kato H, Bodin L, Shattil SJ. Platelet integrin adhesive functions and signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2007;426:103–115. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)26006-9. doi:S0076-6879(07)26006-9 [pii] 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)26006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reininger AJ, Heijnen HF, Schumann H, Specht HM, Schramm W, Ruggeri ZM. Mechanism of platelet adhesion to von Willebrand factor and microparticle formation under high shear stress. Blood. 2006;107:3537–3545. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0618. doi:2005-02-0618 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley JW, Oler A, Tolley ND, et al. Genome wide RNA-seq analysis of human and mouse platelet transcriptomes. Blood. 2011 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-339705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri ZM, Orje JN, Habermann R, Federici AB, Reininger AJ. Activation-independent platelet adhesion and aggregation under elevated shear stress. Blood. 2006;108:1903–1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-011551. doi:blood-2006-04-011551 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2006-04-011551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaier AA, Zou Z, Kazlauskas A, et al. Molecular priming of Lyn by GPVI enables an immune receptor to adopt a hemostatic role. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21167–21172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906436106. doi:0906436106 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0906436106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwertz H, Rowley JW, Tolley ND, Campbell RA, Weyrich AS. Assessing protein synthesis by platelets. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;788:141–153. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-307-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple JW, Italiano JE, Jr, Freedman J. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:264–274. doi: 10.1038/nri2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil SJ. The beta3 integrin cytoplasmic tail: protein scaffold and control freak. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):210–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03397.x. doi:JTH3397 [pii] 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil SJ, Brass LF. Induction of the fibrinogen receptor on human platelets by intracellular mediators. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:992–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil SJ, Newman PJ. Integrins: dynamic scaffolds for adhesion and signaling in platelets. Blood. 2004;104:1606–1615. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil SJ, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:288–300. doi: 10.1038/nrm2871. doi:nrm2871 [pii] 10.1038/nrm2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signarvic RS, Cierniewska A, Stalker TJ, et al. RGS/Gi2alpha interactions modulate platelet accumulation and thrombus formation at sites of vascular injury. Blood. 2010;116:6092–6100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-283846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegner D, Nieswandt B. Platelet receptor signaling in thrombus formation. J Mol Med. 2011;89:109–121. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki-Inoue K, Inoue O, Ding G, et al. Essential in vivo roles of the C-type lectin receptor CLEC-2: embryonic/neonatal lethality of CLEC-2-deficient mice by blood/lymphatic misconnections and impaired thrombus formation of CLEC-2-deficient platelets. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24494–24507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.130575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DW, Mannon RB, Mannon PJ, et al. Coagulation defects and altered hemodynamic responses in mice lacking receptors for thromboxane A2. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1994–2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI5116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga-Szabo D, Braun A, Nieswandt B. STIM and Orai in platelet function. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu T-KH, Hung DT, Wheaton VI, Coughlin SR. Molecular cloning of a functional thrombin receptor reveals a novel proteolytic mechanism of receptor activation. Cell. 1991;64:1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90261-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannemacher KM, Zhu L, Jiang H, et al. Diminished contact-dependent reinforcement of Syk activation underlies impaired thrombus growth in mice lacking Semaphorin 4D. Blood. 2010;116:5707–5715. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279943. doi:blood-2010-04-279943 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins NA, Gusnanto A, de Bono B, et al. A HaemAtlas: characterizing gene expression in differentiated human blood cells. Blood. 2009;113:e1–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162958. doi:blood-2008-06-162958 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrich AS, Dixon DA, Pabla R, Elstad MR, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Signal-dependent translation of a regulatory protein, Bcl-3, in activated human platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5556–5561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde JI, Retzer M, Siess W, Watson SP. ADP-induced platelet shape change: an investigation of the signalling pathways involved and their dependence on the method of platelet preparation. Platelets. 2000;11:286–295. doi: 10.1080/09537100050129305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, Liu Y, Yip J, et al. CEACAM1 negatively regulates platelet-collagen interactions and thrombus growth in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2009;113:1818–1828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165043. doi:blood-2008-06-165043 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woulfe D, Jiang H, Mortensen R, Yang J, Brass LF. Activation of Rap1B by Gi family members in platelets. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23382–23390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woulfe D, Jiang H, Morgans A, Monks R, Birnbaum M, Brass LF. Defects in secretion, aggregation, and thrombus formation in platelets from mice lacking Akt2. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:441–450. doi: 10.1172/JCI20267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Wu J, Kowalska MA, et al. Loss of signaling through the G protein, Gz, results in abnormal platelet activation and altered responses to psychoactive drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9984–9989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180194597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]