Abstract

Agar dilution MIC methodology was used to compare the activity of WCK 771 with those of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, piperacillin, piperacillin-tazobactam, imipenem, clindamycin, and metronidazole against 350 anaerobes. Overall, the MICs (in micrograms per milliliter) at which 50 and 90%, respectively, of the isolates tested were inhibited were as follows: WCK 771, 0.5 and 2.0; ciprofloxacin, 2.0 and 32.0; levofloxacin, 1.0 and 8.0; gatifloxacin, 0.5 and 4.0; moxifloxacin, 0.5 and 4.0; piperacillin, 2.0 and 64.0; piperacillin-tazobactam, ≤0.125 and 8.0; imipenem, 0.125 and 1.0; clindamycin, 0.125 and 16.0; and metronidazole, 1.0 and >16.0.

Anaerobes are becoming increasingly resistant to β-lactams due to β-lactamase production and other mechanisms. Although β-lactamase production, and concomitant resistance to β-lactams, is the norm among the Bacteroides fragilis group, other anaerobic gram-negative bacilli in the genera Prevotella, Porphyromonas, and Fusobacterium have increasingly become β-lactamase positive. β-Lactamase production also has been described for clostridia. Metronidazole resistance in organisms other than non-spore-forming gram-positive bacilli has been described, as has clindamycin resistance in anaerobic gram-negative bacilli (1-3).

Quinolones such as ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, fleroxacin, pefloxacin, enoxacin, and lomefloxacin are inactive or marginally active against anaerobes. Newer quinolones with increased antianaerobic activity include (i) those with slightly increased activity against aerobic gram-positive and some nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria (sparfloxacin, grepafloxacin, and levofloxacin) and (ii) those with significantly improved antianaerobic activity (garenoxacin, clinafloxacin, and sitafloxacin are the most active, followed by trovafloxacin, moxifloxacin, and gatifloxacin) (5-9, 11, 12, 18, 20). Development and/or marketing of many of the latter quinolones has been discontinued.

During the past few years, several reports on quinolone-resistant anaerobic strains with defined quinolone resistance mechanisms (efflux or type II topoisomerase mutations) have been published (4, 14, 15, 17). Plasmid-mediated complementation of gyrA and gyrB in quinolone-resistant B. fragilis has also been described (16). Additionally Golan and coworkers (10) have recently described the emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance among Bacteroides species. Increased use of quinolones against mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections will probably lead to an increased incidence of these strains, but this hypothesis will need validation by future in vitro surveys.

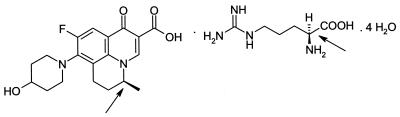

WCK 771 (Fig. 1), an experimental fluoroquinolone, is the hydrate of the arginine salt of S-(−)-nadifloxacin and has expanded gram-positive and -negative activity. The present study tested the antianaerobic activity of WCK 771 compared to those of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin, piperacillin, piperacillin-tazobactam, imipenem, clindamycin, and metronidazole against 350 anaerobes. All anaerobes were clinical strains isolated during the past 4 years, identified by standard procedures (19), and kept frozen in double-strength skim milk (dehydrated skim milk; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at −70°C until use. Prior to testing, strains were subcultured twice onto enriched brucella agar plates supplemented with hemin and vitamin K1 (13). WCK 771 susceptibility powder was provided by Wockhardt Research Center, Aurangabad, India. MICs were based upon the weight of the fluoroquinolone moiety. Other drugs were obtained from their manufacturers. β-Lactamase testing was by the nitrocefin disk method (Cefinase; BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.). Agar dilution susceptibility testing was according to the latest method recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (13), using brucella agar supplemented with hemin, vitamin K1, and 5% sterile defibrinated sheep blood. Tazobactam was added to piperacillin at a fixed concentration of 4.0 μg/ml. All anaerobe quality control gram-negative and -positive strains recommended by NCCLS were included with each run; in every case, the results (where available) were in range. No studies on efflux or type II topoisomerase mutations were performed with quinolone-resistant strains.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of WCK 771. Arrows show chiral structure.

Among the anaerobic gram-negative bacilli tested, 49 of 54 (90.7%) of B. fragilis group strains, 56 of 104 (53.8%) of Prevotella and Porphyromonas strains, and 2 of 47 (4.3%) fusobacteria produced β-lactamase. The results of MIC testing are presented in Table 1. Overall, the MICs (in micrograms per milliliter) at which 50 and 90%, respectively, of the isolates tested were inhibited were as follows: WCK 771, 0.5 and 2.0; ciprofloxacin, 2.0 and 32.0; levofloxacin, 1.0 and 8.0; moxifloxacin, 0.5 and 4.0; gatifloxacin, 0.5 and 4.0, piperacillin, 2.0 and 64.0; piperacillin-tazobactam, ≤0.125 and 8.0; imipenem, 0.125 and 1.0; clindamycin, 0.125 and 16.0; and metronidazole, 1.0 and >16.0.WCK 771 had MICs which were generally one or two dilutions lower than those of gatifloxacin but similar to those of moxifloxacin against all anaerobe groups.

TABLE 1.

MICs of agents

| Organism (no. of β-lactamase-positive strains/no. tested) and drug | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | 50% | 90% | |

| Bacteroides fragilis (11/11) | |||

| WCK 771 | 1->32 | 1 | 16 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2->32 | 4 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 1->32 | 2 | 32 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5->32 | 0.5 | 16 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.5->32 | 0.5 | 8 |

| Piperacillin | 2->128 | 16 | >128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 0.5-4 | 2 | 2 |

| Imipenem | 0.06-2 | 0.25 | 2 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Clindamycin | 0.125-2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron (11/11) | |||

| WCK 771 | 1-8 | 1 | 2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 16->32 | 16 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 4->32 | 4 | 8 |

| Gatifloxacin | 1-32 | 2 | 4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 1-16 | 2 | 2 |

| Piperacillin | 16-64 | 64 | 64 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 4-16 | 16 | 16 |

| Imipenem | 0.125-0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Metronidazole | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Clindamycin | 0.125->32 | 4 | >32 |

| Bacteroides distasonis (6/11) | |||

| WCK 771 | 1-2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4-16 | 4 | 8 |

| Levofloxacin | 1-4 | 2 | 2 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Piperacillin | 4->128 | 64 | >128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 4-16 | 4 | 4 |

| Imipenem | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Metronidazole | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Clindamycin | 0.03->32 | 8 | 16 |

| Bacteroides vulgatus (10/10) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.25-16 | 0.5 | 16 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 16->32 | 16 | 32 |

| Levofloxacin | 1->32 | 2 | >32 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5-16 | 0.5 | 16 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-16 | 0.5 | 16 |

| Piperacillin | 8->128 | 16 | >128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 0.25->32 | 4 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 0.25-2 | 1 | 1 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | 0.03 | 0.5 |

| Miscellaneous Bacteroides (11/11)b | |||

| WCK 771 | 1-8 | 2 | 4 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8->32 | 8 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 4->32 | 4 | >32 |

| Gatifloxacin | 1-16 | 2 | 16 |

| Moxifloxacin | 1-16 | 1 | 8 |

| Piperacillin | 16->128 | 128 | >128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 1-8 | 2 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 0.125-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Clindamycin | 0.5->32 | 4 | >32 |

| Bacteroides fragilis group (49/54) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.25->32 | 1 | 8 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2->32 | 16 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 1->32 | 4 | 32 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.5->32 | 1 | 16 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25->32 | 1 | 8 |

| Piperacillin | 2->128 | 32 | >128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 0.25->32 | 4 | 16 |

| Imipenem | 0.06-2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-2 | 1 | 1 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | 2 | >32 |

| Prevotella bivia (26/42) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.25->32 | 1 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8->32 | 16 | 8 |

| Levofloxacin | 2->32 | 4 | 8 |

| Gatifloxacin | 1->32 | 4 | 4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 2->32 | 4 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | 1-128 | 4 | 32 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | 0.03-0.25 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Metronidazole | 0.5-8 | 2 | 4 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Prevotella corporis (4/12) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.06-1 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5-2 | 1 | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.5-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-32 | 1 | 16 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | 0.016-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016-32 | ≤0.016 | ≤0.016 |

| Prevotella intermedia (6/10) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.06-1 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5-8 | 1 | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5-8 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-2 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-8 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-16 | 2 | 8 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.008-0.125 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | ≤0.016 | ≤0.016 |

| Prevotella melaninogenica (9/10) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.125-8 | 0.125 | 8 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1-16 | 2 | 8 |

| Levofloxacin | 1-32 | 1 | 16 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-16 | 1 | 16 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.5-16 | 1 | 16 |

| Piperacillin | 0.5-64 | 4 | 64 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.008-0.125 | 0.016 | 0.125 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016-0.03 | ≤0.016 | ≤0.016 |

| Prevotella buccae (2/11) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.125-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1-4 | 2 | 4 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Piperacillin | 1-8 | 2 | 4 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.016 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | 0.03-0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Metronidazole | 0.5-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016-0.03 | ≤0.016 | ≤0.016 |

| Miscellaneous Prevotella and Porphyromonas (9/19)c | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.03-1 | 0.125 | 0.5 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5-4 | 1 | 2 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.125-8 | 1 | 1 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.06-2 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-128 | 8 | 128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-8 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.008-0.25 | 0.03 | 0.125 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-4 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | ≤0.016 | 0.06 |

| Prevotella and Porphyromonas (56/104) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.03->32 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5->32 | 2 | 32 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.125->32 | 1 | 8 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.06->32 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125->32 | 1 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-128 | 4 | 64 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-8 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.008-0.25 | 0.03 | 0.125 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-8 | 1 | 4 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | ≤0.016 | 0.06 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum (0/12) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.125-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2-4 | 2 | 4 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125-0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.008-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-0.5 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016-0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Fusobacterium necrophorum (0/12) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.25-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1-4 | 2 | 2 |

| Levofloxacin | 1-4 | 2 | 2 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-2 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-1 | ≤0.125 | ≤0.125 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.008-1 | 0.016 | 0.06 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-0.25 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016-0.125 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Fusobacterium mortiferum (2/11) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.125-0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5-4 | 2 | 2 |

| Levofloxacin | 1-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.5-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Piperacillin | 0.25->128 | 0.5 | >128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Imipenem | 0.25-1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | 0.06-0.5 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Fusobacterium varium (0/12) | |||

| WCK 771 | 4->32 | 8 | 16 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 4->32 | 8 | 16 |

| Levofloxacin | 4->32 | 4 | 8 |

| Gatifloxacin | 2->32 | 4 | 4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 2->32 | 4 | 8 |

| Piperacillin | 4-32 | 8 | 32 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 2-16 | 8 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 0.5-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-1 | ≤0.125 | 0.5 |

| Clindamycin | 2->32 | 32 | >32 |

| Fusobacteria (2/47) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.125->32 | 0.5 | 8 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5->32 | 2 | 8 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5->32 | 2 | 4 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25->32 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125->32 | 1 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125->128 | 0.25 | 16 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-16 | ≤0.125 | 8 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.008-2 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-1 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | 0.06 | 32 |

| Peptostreptococci (0/27)d | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.03-4 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25-16 | 1 | 4 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25-16 | 2 | 4 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.125-8 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125-4 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-2 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-2 | ≤0.125 | 0.25 |

| Imipenem | 0.016-0.5 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-4 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016-8 | 0.125 | 1 |

| Propionibacteria (0/20) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.125-1 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5-1 | 1 | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25-0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Piperacillin | 0.5-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-2 | 0.25 | 1 |

| Imipenem | 0.016-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Metronidazole | >16 | >16 | >16 |

| Clindamycin | 0.03-0.25 | 0.06 | 0.125 |

| Lactobacillus (0/12) | |||

| WCK 771 | 1-32 | 2 | 16 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 1->32 | 2 | >32 |

| Levofloxacin | 1->32 | 2 | >32 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-16 | 0.5 | 8 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-8 | 0.5 | 8 |

| Piperacillin | 1-2 | 2 | 2 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 1-2 | 2 | 2 |

| Imipenem | 0.25-4 | 1 | 2 |

| Metronidazole | 16->16 | >16 | >16 |

| Clindamycin | 0.125-4 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Eubacterium lentum (0/11) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.25-0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125-0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Piperacillin | 16-32 | 16 | 16 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Imipenem | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Metronidazole | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Clindamycin | 0.125->32 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Other gram-positive non-spore- forming bacilli (0/15)e | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.25-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.5-32 | 4 | 16 |

| Levofloxacin | 1-8 | 4 | 4 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-2 | 1 | 2 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-2 | 2 | 2 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-4 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Imipenem | 0.016-0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Metronidazole | 0.5->16 | >16 | >16 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | 0.03 | >32 |

| Clostridium perfringens (0/25) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.03-0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25-2 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 0.06-0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| Metronidazole | 0.5-2 | 1 | 1 |

| Clindamycin | 0.03-2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Clostridium difficile (0/12) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.5-4 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 8->32 | 16 | 16 |

| Levofloxacin | 4->32 | 4 | 8 |

| Gatifloxacin | 1-16 | 2 | 2 |

| Moxifloxacin | 1-8 | 1 | 2 |

| Piperacillin | 8-16 | 8 | 16 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 8-32 | 8 | 16 |

| Imipenem | 4-8 | 8 | 8 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Clindamycin | 4->32 | 8 | >32 |

| Miscellaneous clostridia (0/23)f | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.03-1 | 0.125 | 1 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25-8 | 2 | 8 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.25-8 | 1 | 8 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.25-4 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.25-4 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125-64 | 1 | 16 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125-32 | 0.25 | 8 |

| Imipenem | 0.03-1 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125-4 | 1 | 4 |

| Clindamycin | 0.03->32 | 2 | 16 |

| All strains (107/350) | |||

| WCK 771 | 0.03->32 | 0.5 | 2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25->32 | 2 | 32 |

| Levofloxacin | 0.125->32 | 1 | 8 |

| Gatifloxacin | 0.06->32 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Moxifloxacin | 0.125->32 | 0.5 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.125->128 | 2 | 64 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | ≤0.125->32 | ≤0.125 | 8 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.008-8 | 0.125 | 1 |

| Metronidazole | ≤0.125->16 | 1 | >16 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.016->32 | 0.125 | 16 |

50% and 90%, MICs at which 50 and 90% of isolates are inhibited, respectively.

Bacteroides ovatus, 7; Bacteroides uniformis, 4.

Prevotella disiens, 9; Prevotella oris, 3; Prevotella loeschii, 2; Prevotella oralis group, 1; Prevotella denticola, 1; Porphyromonas asaccharolytica, 2; Porphyromonas gingivalis, 1.

Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus, 2; Peptostreptococcus magnus, 6; Peptostreptococcus micros, 6; Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, 5; Peptostreptococcus tetradius, 6; Peptostreptococcus prevotii, 2.

Actinomyces sp., 6; Bifidobacterium sp., 9.

Clostridium tertium, 6; Clostridium bifermentans, 3; Clostridium cadaveris, 3; Clostridium sordellii, 4; Clostridium ramosum, 3; Clostridium paraputrificum, 1; Clostridium hystoliticum, 1; Clostridium sp., 2.

Although the overall WCK 771 MIC at which 90% of the isolates tested were inhibited was one dilution lower than that of moxifloxacin, for the five groupings of B. fragilis group species, moxifloxacin was more active than WCK 771 against two species, inferior against one, and the same against two more. For Prevotella species, WCK 771 was more active than moxifloxacin for most species, and there was an even split for fusobacteria. All quinolones tested had high MICs against Fusobacterium varium and lactobacilli. Additionally, higher quinolone MICs were observed against B. fragilis and Bacteroides vulgatus strains than against other members of the B. fragilis group. Among Prevotella spp., quinolone MICs were higher for P. melaninogenica than for other members of this genus. Moxifloxacin was more active than WCK 771 for peptostreptococci, lactobacilli, and Eubacterium lentum but was inferior by comparison against clostridia. Because strains for which quinolone MICs were raised were not studied for resistance mechanisms, accurate comparisons with recent publications on this aspect cannot be made. The addition of tazobactam enhanced the activity of piperacillin against β-lactamase-producing anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. Although most strains tested were susceptible to clindamycin (MICs of ≤2 μg/ml), resistance was seen in some gram-negative anaerobic rods, peptostreptococci, anaerobic gram-positive non-spore-forming rods, and clostridia. The only anaerobes resistant to metronidazole were the anaerobic gram-positive bacilli.

WCK 771 is a new experimental fluoroquinolone with expanded activity against pneumococci and staphylococci (M. V. Patel, S. V. Gupte, S. K. Agarwal, D. J. Upadhyay, K. Sreenivas, Y. Chugh, N. Shetty, R. K. Beri, N. J. De Souza, and N. Khorakiwala, Abstr. 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-539, 2001; G. A. Pankuch, M. Jacobs, H. Khorakiwala, N. De Souza, M. Patel, and P. C. Appelbaum, Abstr. 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-541, 2001; M. R. Jacobs, S. Bajaksouzian, A. Windau, M. V. Patel, N. de Souza, H. Khorakiwala, and P. C. Appelbaum, Abstr. 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. F-542, 2001). Of all quinolones tested in our study, WCK 771 had the lowest overall MICs for all strains tested; no previous data on this have been previously available, to our knowledge. The MICs of ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, gatifloxacin, and moxifloxacin are similar to those reported previously by us and other workers, while the MICs of nonquinolone agents also reflect previous findings, with low MICs of piperacillin-tazobactam and imipenem against β-lactamase-positive and -negative strains and good activity of clindamycin (except against a few gram-negative and -positive rods and clostridia) and metronidazole (except against gram-positive non-spore-forming rods). The few strains for which quinolone MICs were consistently high were predominantly F. varium, a rare human pathogen which is more resistant to fluoroquinolones and other antimicrobials than are other fusobacteria (5-7, 9, 11, 12, 18). The strains studied were isolated during the past 4 years, and we did not observe the increase in quinolone resistance described by Golan and coworkers (10).

The results of this first published in vitro anaerobe study suggest a potential place for WCK 771, with MICs similar to those of moxifloxacin, in treatment of anaerobic and mixed infections where strains of the B. fragilis group do not play a major role (e.g., infections of the respiratory tract, skin, and soft tissue), provided that a breakpoint of <4.0 μg/ml can be achieved. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic and experimental animal studies are necessary to further delineate the clinical role of these new quinolones in therapy of anaerobic infections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appelbaum, P. C., A. Philippon, M. R. Jacobs, S. K. Spangler, and L. Gutmann. 1990. Characterization of β-lactamases from non-Bacteroides fragilis group Bacteroides spp. belonging to seven species and their role in β-lactam resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:2169-2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelbaum, P. C., S. K. Spangler, and M. R. Jacobs. 1990. β-Lactamase production and susceptibilities to amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, ticarcillin, ticarcillin-clavulanate, cefoxitin, imipenem, and metronidazole of 320 non-Bacteroides fragilis Bacteroides and 129 fusobacteria from 28 U.S. centers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1546-1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelbaum, P. C., S. K. Spangler, G. A. Pankuch, A. Philippon, M. R. Jacobs, R. Shiman, E. J. C. Goldstein, and D. Citron. 1994. Characterization of a β-lactamase from Clostridium clostridioforme. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachoual, R., L. Dubreuil, C.-J. Soussy, and J. Tankovic. 2000. Roles of gyrA mutations in resistance of clinical isolates and in vitro mutants of Bacteroides fragilis to the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1842-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry, A. L., and P. C. Fuchs. 1991. In vitro activities of sparfloxacin, tosufloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and fleroxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:955-960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barry, A. L., P. C. Fuchs, D. M. Citron, S. D. Allen, and H. M. Wexler. 1993. Methods for testing the susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria to two fluoroquinolone compounds, PD 131628 and clinafloxacin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31:893-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauernfeind, A. 1993. Comparative in vitro activities of the new quinolone, Bay y3118, and ciprofloxacin, sparfloxacin, tosufloxacin, CI-960 and CI-990. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31:505-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauernfeind, A. 1997. Comparison of the antibacterial activities of the quinolones Bay 12-8039, gatifloxacin (AM 1155), trovafloxacin, clinafloxacin, levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:639-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ednie, L. M., M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1998. Activities of gatifloxacin compared to those of seven other agents against anaerobic organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2459-2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golan, Y., L. A. McDermott, N. V. Jacobus, E. J. C. Goldstein, S. Finegold, L. J. Harrell, D. W. Hecht, S. G. Jenkins, C. Pierson, R. Venezia, J. Rihs, P. Iannini, S. L. Gorbach, and D. R. Snydman. 2003. Emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance among Bacteroides species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:208-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein, E. J. C., and D. M. Citron. 1992. Comparative activity of ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, sparfloxacin, temafloxacin, CI-960, CI-990, and Win 57273 against anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1158-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoellman, D. B., L. M. Kelly, M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2001. Comparative antianaerobic activity of BMS 284756. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:589-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2004. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria, 5th ed. Approved standard. NCCLS publication M11-A6. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 14.Oh, H., and C. Edlund. 2003. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance in anaerobic bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 9:512-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh, H., N. El Amin, T. Davies, P. C. Appelbaum, and C. Edlund. 2001. GyrA mutations associated with quinolone-resistance in Bacteroides fragilis group strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1977-1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson, M. L., J. C. Rotshafer, and L. J. V. Piddock. 2003. Plasmid-mediated complementation of gyrA and gyrB in fluoroquinolone-resistant Bacteroides fragilis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:481-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricci, V., M. L. Peterson, J. C. Rotschafer, H. Wexler, and L. J. V. Piddock. 2004. Role of topoisomerase mutations and efflux in fluroquinolone resistance of Bacteroides fragilis clinical isolates and laboratory mutants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1344-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spangler, S. K., M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1994. Activity of CP 99,219 compared with those of ciprofloxacin, grepafloxacin, metronidazole, cefoxitin, piperacillin, and piperacillin-tazobactam against 489 anaerobes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2471-2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Summanen, P., E. J. Baron, D. M. Citron, C. A. Strong, H. M. Wexler, and S. M. Finegold. 1993. Wadsworth anaerobic bacteriology manual, 5th ed. Star Publishing Co., Belmont, Calif.

- 20.Wexler, H. M., E. Molitoris, D. Molitoris, and S. M. Finegold. 1996. In vitro activities of trovafloxacin against 557 strains of anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2232-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]