Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the leading heritable cause of intellectual disability (Boyle and Kaufmann, 2010) and most prevalent single-gene autism spectrum disorder (Wang et al., 2012). The disease state is caused by lack of Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP), a key regulator of activity-dependent neural circuit modulation during critical period development (Doll and Broadie, 2014). The full range of FMRP function is broad and inconclusive, but includes regulation of multiple classes of voltage-gated ion channels, via both RNA-binding translational control (Gross et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011; Strumbos et al., 2010) and direct channel-binding interactions (Brown et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2013; Ferron et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014). Downstream, FMRP also regulates numerous calcium-binding proteins (CaBPs) involved in activity-dependent calcium signaling (Chen et al., 2003; Tessier and Broadie, 2011; Wang et al., 2009). Consistently, FXS disease models exhibit increased excitatory neurotransmission (Deng et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2011; Gibson et al., 2008), defects in action potential termination (Brown et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012) and altered depolarization-triggered calcium influx (Deng et al., 2013; Deng et al., 2011; Ferron et al., 2014; Patel et al., 2013; Tessier and Broadie, 2011). Earlier work has elegantly mapped critical period functional refinement (Meredith, 2015), and defining FMRP roles in these activity-dependent mechanisms at single cell resolution during critical periods is now possible through the application of incisive Drosophila genetics.

The Drosophila FXS disease model has long been instrumental in dissecting developmental and activity-dependent FMRP roles (Doll and Broadie, 2015; Gatto and Broadie, 2008; Pan et al., 2004; Tessier and Broadie, 2008; Weisz et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2001). Our past studies have identified hyper-excitability, calcium influx and store release defects, and changes in CaBP expression in the absence of FMRP function (Gatto and Broadie, 2008; Repicky and Broadie, 2009; Tessier and Broadie, 2008; Tessier and Broadie, 2011). During development of the well-mapped Mushroom body (MB) learning/memory circuit, we recently identified activity-dependent and FMRP-dependent changes in synaptic connectivity coincident with the early-use sensory input critical period that occurs immediately following eclosion (Doll and Broadie, 2015). Individually identified single cells of opposing excitatory input and inhibitory output neuron classes exhibit opposite activity-dependent responses to optogenetic stimulation and hyperpolarization, effects that require FMRP specifically during this critical period.

The present study investigates the neuron class-specific FMRP functional requirements in excitatory vs. inhibitory neurons in calcium signaling dynamics during MB critical period circuit development (Kaeser and Regehr, 2014). Our working hypothesis at the onset of this study was that FMRP regulates Ca2+ signaling dynamics in a cell type-specific manner in excitatory vs. inhibitory neurons, with a heightened requirement during the early-use MB critical period immediately following eclosion. The sophisticated Drosophila genetic toolkit is especially well suited for this cell-specific and developmental stage-specific dissection through the application of new highly-targeted neuronal transgenic drivers and conditional genetic manipulations. Our goal in this study was to elucidate the functional differences underlying activity-dependent development of these two distinct excitatory vs. inhibitory neuron types, utilizing calcium imaging within the Drosophila learning/memory circuit (Tomchik and Davis, 2009).

We focused on two MB extrinsic neurons; excitatory cholinergic input AL-mPN2 (Ito et al., 2014) and inhibitory GABAergic output MBON-γ1pedc>α/β (Aso et al., 2014b). We find that FMRP regulates calcium signaling dynamics in these two neuron classes in an opposite manner during early-use critical period development. In cholinergic projection neurons carrying excitatory input from olfactory antennal lobe to MB calyx (Iniguez et al., 2013), FMRP absence leads to elevated calcium transients only during the critical period. In contrast, the MBON-11 GABAergic output neurons, which are postsynaptic to Kenyon Cells at the MB spur (Tanaka et al., 2008), display reduced calcium transients in dfmr1 null mutants, but also only during the critical period. Cell autonomous rescue and knockdown demonstrate a specific critical period FMRP requirement in both neuron classes. Cell autonomous optogenetic stimulation during the critical period causes heightened activity-dependent calcium transients, indicating that critical period activity modulates subsequent excitability. Importantly, heightened critical period activity in excitatory neurons induced calcium signaling dynamics strikingly reminiscent of FXS, supporting the hyperexcitation theory of FXS and providing a developmental mechanism for the excitation/inhibition imbalance characterizing the disease state (Gatto and Broadie, 2010). These results demonstrate neuron class-specific functional roles for FMRP restricted to critical period development.

Materials & Methods

Drosophila genetics

All stocks were reared on standard cornmeal/agar/molasses food at 25°C unless stated otherwise. Multiple recombinant lines of dfmr1 null allele dfmr150M (Zhang et al., 2001) were generated with standard genetic techniques using a combination of the following transgenic lines; 1) R12G04-Gal4, R65G01-Gal4, 20XUAS-IVS-GCamp5G and tubP-Gal80[ts];TM2/TM6 from the Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN, USA), 2) UAS-dfmr1-RNAi (TRiP, Harvard) and 3) UAS-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry generously provided by Leslie Griffith (Pulver et al., 2009). For conditional Gal80ts dfmr1-RNAi and wildtype dfmr1-rescue (UAS-9557-3, wildtype dfmr1 under UAS control; Gatto and Broadie, 2009) experiments, both controls and experimental animals were raised at permissive 18°C (Gal80ts active) until the last pupal day (P4), and then shifted to restrictive 29°C (Gal80ts inactive) until 1 day post-eclosion (dpe).

Immunocytochemistry and imaging

Immunocytochemistry was carried out as previously described (Doll and Broadie, 2015). Primary rabbit anti-GFP (ab290; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used at a 1:2000 dilution, and secondary antibody anti-mouse-IgG AlexaFluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used at a 1:500 dilution. Images were acquired for the central brain region on a Zeiss Meta 510 confocal microscope with 40-100X objectives, and collected as Z-stacks of 1μm section depth.

Calcium imaging

The 20XUAS-IVS-GCamp5G line (Bloomington stock center #42037) was used as a transgenic [Ca2+] reporter (Akerboom et al., 2012). This reporter was crossed to R12G04-Gal4 and R65G01-Gal4 driver lines in both w1118 genetic background control and dfmr1 null mutant backgrounds. Acutely dissected brains from all four genotypes were immobilized on 30 mm petri dishes in 3 mL of physiological saline containing 128 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 35.5 mM sucrose, 5 mM Hepes, and 1.8 mM Ca2+, pH 7.2 (Tessier and Broadie, 2011). Labeled cell soma were immediately imaged with a 40x water-immersion objective with maximal pinhole aperture on a Zeiss LSM510Meta laser-scanning confocal microscope. Each neuron was outlined using a region of interest (ROI) box, and a time series was captured at 128x128 resolution at maximum scanning speeds (44ms/frame). Baseline fluorescence was determined for each selected neuron (~350 frames/15 sec), followed by acute K+ depolarization (60 mM KCl) (Gatto et al., 2014) with recording for 2500 total frames (110 secs). ImageJ was used for image registration and determination of baseline fluorescence intensity values within the ROI (Schneider et al., 2012). Baseline fluorescence was defined from a 20-frame average that occurred in the 5 seconds prior to the onset of transient initiation and was used to normalize the data set. Data were plotted as the relative change in fluorescence from baseline divided by the baseline (ΔF/F; (Ft1 – Fbaseline)/Fbaseline), with each data point representing an average and standard error of 20 frames. Line graph data points represent an average of 20 frames (captured at 44 ms/frame), therefore every data point represents 880 ms. Only one calcium transient was captured from each individual neuron, and only one neuron was analyzed from each animal. Time to peak [Ca2+] was calculated by averaging raw individual trace data, locating the frame with the greatest fluorescence value in each trial, relative to the initiation of the transient (in seconds: frame # x 0.0044 s). Average peak fluorescence values compare the maximum 20 frame fluorescent values from each group of transient initiation-aligned traces. Only individual traces with half-life decay functions in which r2 > 0.9 were included in decay analyses. Decay half-life (t1/2) was estimated using the least-squares method to fit the 20% to 80% decay fluorescence to a single-exponential function Y=Y0e−kt where t1/2=ln2/k in MATLAB (version R2012b, Mathworks, Natick, MA).

Optogenetics

Transgenic animals were generated from pairwise crosses between the UAS-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry optogenetic channel line and 1 of 2 drivers (R12G04-Gal4 or R65G01-Gal4), both in w1118 genetic background control and dfmr1 null mutant backgrounds. Offspring from all four genotypes were fed from hatching on standard food supplemented with either 10μL EtOH (in 10 ml volume; vehicle control) or 100μM all-trans retinal (ATR), an essential co-factor for channelrhodopsin function (Ataman et al., 2008). Upon eclosion, developmentally staged animals were placed in 30mm petri dishes with Watman paper strips saturated in a 20% sucrose solution containing either the vehicle control or 100μM ATR. All control and experimental animals were placed in a LED exposure chamber with two 470nm blue light Luxeon Rebel Endor Star 3X 15-Watt LED arrays (LED Supply, Randolph, VT). At 15V, the LED arrays generate ~100 μW/cm2 of blue light at the working distance of 2cm. Animals were exposed to 24 hrs of 20ms light pulses at 5Hz frequency. Brains from light-exposed animals then underwent Ca2+ imaging as described above.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using Instat or Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data from two group comparisons were analyzed with a two-tailed unpaired t-test. Data from three group or more comparisons were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett post hoc tests were applied to compare individual experimental groups to control (F and p values reported). Transient initiation-aligned traces (mean ± standard error) for each genotype are presented in line graphs. Data are presented in box-and-whisker plots (minimum, median, maximum and quartiles). Sample size definitions for peak amplitude, time to peak amplitude and decay half-life, n = number of individual transient recordings (1 transient per neuron, per animal). Significance levels in figures are represented as p>0.05 (not significant, n.s.), p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**) and p<0.001 (***).

Results

FMRP-defined critical period development in excitatory vs. inhibitory MB circuit neurons

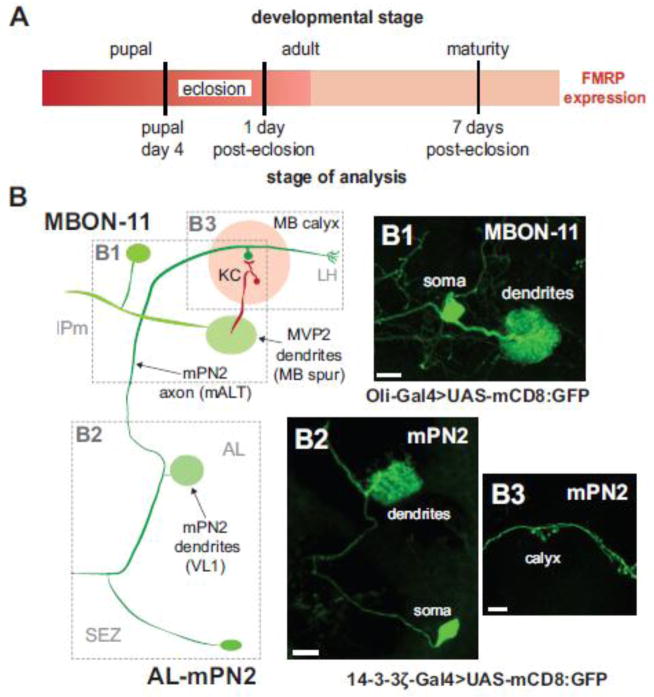

FMRP shows a tight peak of expression from the last day of pupal development (P4) though the first day post-eclosion (1 dpe) that defines an early-use critical period of activity-dependent neural circuit refinement (Fig. 1A; Tessier and Broadie, 2008; Tessier and Broadie, 2012). Following this window, FMRP levels rapidly fall to much lower steady-state expression in the mature brain (e.g. 7 dpe; Fig. 1A). Our recent work revealed a restricted temporal FMRP requirement in the development of MB synaptic connectivity during this critical period, with opposite activity-dependent directionality in two opposite classes of MB extrinsic neurons; an excitatory input neuron and an inhibitory output neuron (Fig. 1B; Doll and Broadie, 2015). To test for the functional mechanism, we assayed activity-dependent Ca2+ dynamics in these two distinctive excitatory vs. inhibitory neuron classes, focusing on the FMRP-defined, early-use critical period window (P4 – 1 dpe) compared to adult maturity (7 dpe; Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Critical period manipulation of excitatory input and inhibitory output neurons of the mushroom body learning/memory circuit. A) Schematic illustrating developmental stages of analysis relative to the FMRP expression profile (Tessier and Broadie, 2008). B) Schematic depicting architecture of MB input excitatory cholinergic neuron AL-mPN2 (R65G01-Gal4 driver) and MB output inhibitory GABAergic neuron MBON-γ1pedc>α/β (MBON-11; R12G04-Gal4 driver). The membrane marker UAS-mCD8 is shown for MBON-11 (B1) and mPN2 (B2, B3) labeling soma, dendritic arbor and axon processes. Dashed boxes correspond to images. Abbreviations: MB, Mushroom body; AL, antennal lobe; ON, output neuron; SEZ, subesophogeal zone; IPm medial inferior protocerebrum; KC, Kenyon cell; LH, lateral horn; VL, vertical lobe; ML, medial lobe; mALT, medial antennal lobe tract; PN, projection neuron; VL1, ventrolateral glomerulus 1; AL-mPN2, antennal lobe medial projection neuron 2. Scale B1: 10μM, B2: 20μM, B3: 10μM.

The highly restricted R65G01-Gal4 (Leonardo/14-3-3δ gene) FlyLight transgenic driver specifically targets the excitatory cholinergic MB input neuron (antennal lobe medial projection neuron 2: AL-mPN2), allowing single-cell resolution recording and manipulation (Fig. 1B; Doll and Broadie, 2015; Jenett et al., 2012). mPN2 cell bodies are located at the ventrolateral edge of the central brain in the subesophogeal zone (SEZ; Ito et al., 2014), with a primary process that travels medially before bifurcation into a collateral and a dorsal branch (Fig. 1B; Tanaka et al., 2012). mPN2 is characterized as a bilateral uniglomerular medial antennal lobe tract (mALT) projection neuron with a dendritic arbor specific to the VL1 glomerulus of the antennal lobe (AL; Fig. 1B2). The axon travels through the mALT, with primary presynaptic outputs to 3–5 microglomeruli in the MB calyx on Kenyon Cells (KCs) as well as further axon terminals in the lateral horn (LH; Fig. 1B3).

The R12G04-Gal4 (Oli gene) FlyLight driver specifically targets the inhibitory GABAergic output neuron MBON-γ1pedc>α/β (abbreviated MBON-11; Aso et al., 2014b), formerly identified as MB-MVP2 (Fig 1B; Aso et al., 2014b; Doll and Broadie, 2015; Jenett et al., 2012). Single MBON-11 neuronal cell bodies are located in the inferiormedial protocerebrum (IPm) in the anterior portion of the central brain, with a prominent dendritic arbor within the MB spur (Fig. 1B1), and an output axon that bifurcates into collateral and vertical branches (Tanaka et al., 2008). These GABAergic MB output neurons are required in multiple sensory modalities (both olfactory and visual) for aversive memory consolidation (Aso et al., 2014b). Our previous work established a tight temporal requirement for FMRP function during the early sensory input critical period in the activity-dependent development of both mPN2 and MBON-11 dendritic arborization (Doll and Broadie, 2015).

Excitatory mPN2 displays an FMRP-dependent developmental shift in Ca2+ dynamics

The FMRP-dependent refinement of MB circuitry is confined to a transient window of development during early sensory use, immediately following eclosion (Doll and Broadie, 2015; Tessier and Broadie, 2008), similar to a comparable requirement in mammals (Portera-Cailliau, 2012). Based on our previous studies, we focused analyses on the 1 dpe critical period compared to the 7 dpe time point representing adult maturity. The GCamp5G transgenic [Ca2+] reporter (Akerboom et al., 2012) was used to assay activity-dependent Ca2+ signaling dynamics in single, individually identified mPN2 and MBON-11 neuronal soma as a function of development time in w1118 genetic background control compared to dfmr1 null mutants. Neurons were imaged to establish baseline GCamp5G fluorescence (1.8mM extracellular bath [Ca2+]) and then acutely depolarized with high [K+] (60mM KCl) to generate optically measurable Ca2+ transients (Fiala and Spall, 2003). Three primary parameters were used to measure the Ca2+ transients: time to peak fluorescence (sec), peak fluorescence intensity and the half-life of transient termination (sec).

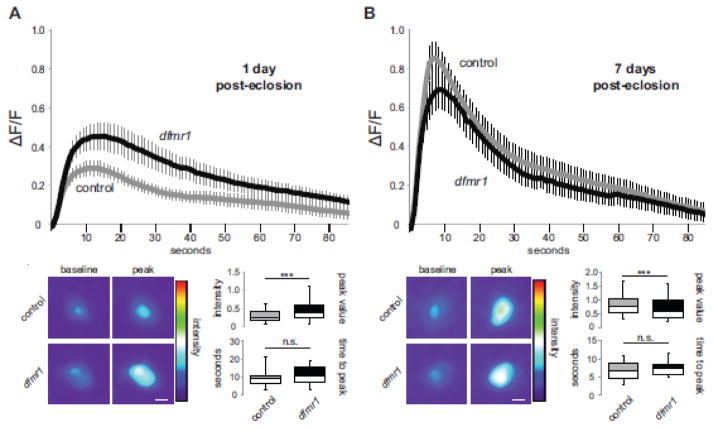

A summary of excitatory mPN2 neuron Ca2+ signaling dynamics at the 1 dpe critical period and at 7 dpe maturity is shown in Figure 2. At 1 dpe, UAS-GCamp5G driven by R65G01-Gal4 provides clear fluorescent Ca2+ reporter transients upon acute K+ depolarization, which display a rapid rise to peak and slower decay (Fig. 2A). Compared to genetic background controls, dfmr1 null mPN2 neurons exhibit a >35% increase in the Ca2+ transient peak (control, 0.29 ± 0.04, n=19 neurons; dfmr1, 0.46 ± 0.07, n=17 neurons, t-test, p=1.25E-20; Fig. 2A). Despite this greatly increased peak amplitude, the time to peak is comparable between genotypes (control, 9.16 ± 0.98 sec, n=19; dfmr1, 10.61 ± 1.20 sec, n=17, t-test, p=0.35). Similarly, both wildtype and dfmr1 null mPN2 neurons display comparable slow Ca2+ transient decay properties (control t1/2, 37.44 ± 5.52 sec, r2=0.96 ± 0.01, n=19; dfmr1 t1/2, 40.82 ± 6.82, r2=0.96 ± 0.01, n=17, p=0.70; Fig. 2A, bottom). These data show that FMRP limits the level of depolarization-induced Ca2+ signaling in mPN2 neurons, but does not impact the rate of Ca2+ clearance. Therefore, the extended calcium signaling profile in dfmr1 nulls (extended return to baseline; Fig. 2A) is likely rooted in elevated influx capacity and not decay properties.

Figure 2.

Restricted critical period defect in AL-mPN2 Ca2+ dynamics in dfmr1 mutants. The UAS-GCamp5G fluorescent reporter driven by R65G01-Gal4 in excitatory mPN2 input neurons to assay depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients in both wildtype control (w1118) and dfmr1 null mutants. Confocal fluorescent measurements done at the peak critical period of 1 day post-eclosion (A) compared to maturity at 7 days post-eclosion (B). Still frame heat map representations of baseline and peak fluorescence following acute K+ depolarization. The change of average fluorescence intensity over time (mean±SEM) is plotted on top, with histograms (minimum, median, maximum and quartiles) below depicting peak intensity and time to peak. nWT-1dpe=19, ndfmr1-1dpe=17, nWT-7dpe=22, ndfmr1-7dpe=18. Statistical significance indicated as ***p<0.001 or not significant (n.s.). Scale bars: 10μm.

At maturity (7 dpe), depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients in excitatory mPN2 neurons have increased dramatically in wildtype (compare Figs. 2A and 2B). In contrast, the developmental change in dfmr1 null mutants is blunted, with a much smaller increase in Ca2+ transient amplitude. As a result, depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients at 7 dpe are largely indistinguishable between wildtype and dfmr1 null mPN2 neurons (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, at maturity the peak fluorescent amplitude is actually moderately reduced (~19%) in dfmr1 nulls (0.69 ± 0.10, n=18 neurons) compared to controls (0.85 ± 0.08, n=22 neurons, t-test, p=1.02E-08; Fig. 2B), underscoring the dramatic developmental shift in wildtype Ca2+ signaling dynamics. The temporal Ca2+ transient characteristics in both control and mutant genotypes are comparable at maturity, including time to peak (control, 6.77 ± 0.55 sec, n=22; dfmr1, 7.57 ± 0.45 sec, n=18, t-test, p=0.29, n.s.; Fig. 2B), and decay half-life (control t1/2, 20.23 ± 2.85 sec, r2=0.97 ± 0.02, n=20; dfmr1 t1/2, 33.89 ± 8.85, r2=0.92 ± 0.02, n=17, t-test, p=0.13, n.s.; Fig. 2B). These results suggest a restricted critical period requirement for FMRP in depolarization-induced Ca2+ signaling, with wildtype undergoing a dramatic developmental shift compared to dfmr1 null mPN2 neurons, establishing comparable functional properties at maturity.

Inhibitory MBON-11 neurons show the opposite developmental shift in Ca2+ dynamics

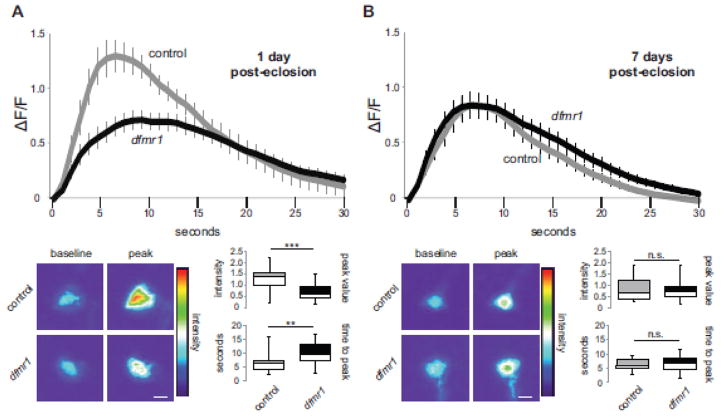

Despite similar dendritic arbor architectural phenotypes, excitatory mPN2 and inhibitory MBON-11 neurons exhibit opposite FMRP-dependent responses to activity during critical period development (Doll and Broadie, 2015). Consistently, the functional Ca2+ signaling dynamics of these two neuron classes also display an opposite critical period specific shift in dfmr1 mutants. At the 1 dpe critical period, acute depolarization of wildtype MBON-11 neurons causes a rapid rise to peak [Ca2+] and a quick decay back to baseline (Fig. 3A). In dfmr1 nulls, however, the 1 dpe Ca2+ transient peak is very significantly reduced in MBON-11 neurons (0.71 ± 0.08, n=20 neurons) compared to controls (1.29 ± 0.14, n=15 neurons, t-test, p=3.95E-53; Fig. 3A). Moreover, the time to peak is significantly longer in dfmr1 null neurons (9.81 ± 0.89 sec, n=15) compared to controls (6.28 ± 0.80 sec, n=20, t-test, p=0.007; Fig. 3A, bottom), although the Ca2+ transient decay half-life is comparable between genotypes (control t1/2, 7.22 ± 1.8, r2=0.95 ± 0.01, n=20; null t1/2, 9.07 ± 1.4 sec, r2=0.94 ± 0.01, n=15, t-test, p=0.41, n.s.). The critical period reduction in Ca2+ transients in dfmr1 null MBON-11 GABAergic neurons contrasts sharply with the elevation in dfmr1 null mPN2 cholinergic neurons, showing a clear distinction between inhibitory and excitatory neurons in the developing MB circuit.

Figure 3.

Opposite critical period defect in MBON-11 Ca2+ dynamics in dfmr1 mutants. UAS-GCamp5G fluorescent reporter targeted by the R12G04-Gal4 driver to inhibitory MBON-11 output neurons to assay depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients in wildtype control (w1118) and dfmr1 null mutants. Measurements at the 1 day post-eclosion critical period (A) compared to maturity at 7 days post-eclosion (B). Representative heat maps show baseline and peak fluorescence following acute K+ depolarization. The change of average fluorescence intensity over time (mean±SEM) is plotted on top, with histograms (minimum, median, maximum and quartiles) below depicting peak intensity and time to peak. nWT-1dpe=20, ndfmr1-1dpe=16, nWT-7dpe=22, ndfmr1-7dpe=23. Statistical significance indicated as **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 or not significant (n.s.). Scale bars: 10μm.

At maturity (7 dpe), wildtype MBON-11 neurons show a clear shift in Ca2+ transient peak fluorescence (0.81 ± 0.11, n=22 neurons), as they undergo a prominent decrease from the developmental critical period to adulthood (compare Figs. 3A and 3B). In contrast to the genetic background control, dfmr1 null MBON-11 neurons retain remarkably similar activity-dependent Ca2+ signaling dynamics at maturity compared to the 1 dpe critical period (compare Figs. 3A and 3B). As in mPN2 neurons, the dfmr1 null peak transient amplitude (0.83 ± 0.10, n=23 neurons, t-test: p=0.55) and time to peak (6.40 ± 0.57 sec, n=23, t-test: p=0.81) in inhibitory MBON-11 neurons were both indistinguishable from controls at maturity (Fig. 3B). The only dfmr1 phenotype remaining at maturity is a significant increase in decay half-life compared to controls (5.88 ± 0.48 sec, r2=0.97 ± 0.01, n=20, t-test: p=0.0266). Taken together, these data show reduced critical period Ca2+ signaling in FXS disease state inhibitory MB output neurons, another transient critical period FMRP requirement that is nearly completely resolved at maturity.

Critical period conditional control of FMRP in excitatory mPN2 neurons

Conditional control of gene function is a powerful method for developmental dissection of neural circuit formation (Bohm et al., 2010; Fore et al., 2011) and disease mechanisms (Frickenhaus et al., 2015; Herrera et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Ng and Jackson, 2015). We demonstrated above that FMRP function is crucial for regulation of Ca2+ dynamics in both mPN2 excitatory neurons and MBON-11 inhibitory neurons only during the early-use critical period and no longer at maturity. To test this apparently restricted FMRP requirement, we next used transgenic techniques to conditionally control FMRP expression only during the critical period and specifically within only the targeted neurons. We first used the Gal80ts repressive technique (McGuire et al., 2003; Tutor et al., 2014) to temporally restore wildtype FMRP to otherwise dfmr1 null mutants in cell-autonomous studies. In our hands, this technique provides a highly targeted method to temporally express FMRP in an otherwise completely FMRP-deficient brain (Doll and Broadie, 2015). For mPN2 neurons, this approach involved first generating and then crossing tubP-Gal80ts; dfmr150M, R65G01-Gal4 to UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr150M, UAS-9557-3 animals. UAS-9557-3 is a genomic wildtype dfmr1 under UAS control. All genotypes were raised at restrictive 18°C and then shifted to permissive 29°C at P4, relieving Gal80ts repression and inducing dfmr1 expression only in mPN2 neurons (Fig. 4A). At the end of the critical period (1 dpe), brains were dissected and acutely depolarized (60mM KCl) to measure Ca2+ transients.

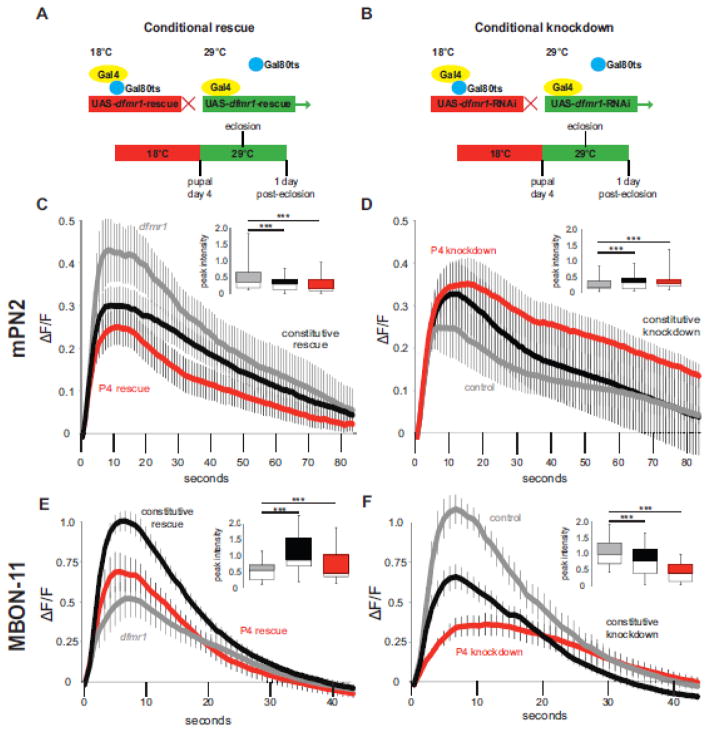

Figure 4.

Conditional dfmr1 rescue/removal shows restricted critical period requirement. Gal80ts repressive paradigm for conditionally dfmr1 rescue (A) and knockdown (B) during critical period development for both excitatory input mPN2 and inhibitory output MBON-11 neurons. Animals raised at 18°C permissive temperature (Gal80 active, Gal4 inactive, red) until pupal day 4 (P4), then shifted to 29°C restrictive temperature (Gal80 inactive, Gal4 active, green) until 1 day post-eclosion (1 dpe). (C–F) K+ depolarization-induced Ca2+ transient GCamp5G fluorescence changes for genetic controls (grey line), constitutively active rescue/RNAi (black line), and conditional Gal80ts rescue/RNAi (red line). AL-mPN2 dfmr1 critical period rescue (dfmr1 control n=15, constitutive rescue n=22, conditional rescue n=25) (C) and RNAi knockdown (WT control n=16, constitutive RNAi n=16, conditional RNAi n=14) (D) shows restricted temporal FMRP requirement. Parallel, MBON-11 critical period rescue (dfmr1 control n=21, constitutive rescue n=23, conditional rescue n=17) (E) and removal (WT control n=15, constitutive RNAi n=21, conditional RNAi n=10) (F) of dfmr1 shows similar results. Each plot represents the change of average fluorescence intensity over time (mean±SEM), and includes an inset peak intensity histogram (minimum, median, maximum and quartiles). Significance determined by one-way ANOVA and indicated as ***p<0.001 or not significant (n.s.).

Wildtype dfmr1 rescue of null phenotypes was tested by comparing three conditions (Fig. 4C): 1) dfmr1 mutants containing all transgenic elements (dfmr150M, R65G01-Gal4>dfmr150M, UAS-GCamp5G; grey line), 2) dfmr1 constitutive rescue (dfmr150M, R65G01-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr150M, UAS-9557-3; black line) and 3) critical period conditional rescue (tubP-Gal80ts; dfmr150M, R65G01-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr150M, UAS-9557-3; red line). Both constitutive (0.30 ± 0.04, n=22 neurons, Dunnett, p<0.001) and critical period-specific rescue (0.25 ± 0.04, n=25 neurons, Dunnett, p<0.001) caused a similar reduction in the peak Ca2+ transient compared to dfmr1 nulls (0.52 ± 0.11, n=15 neurons, F(2,57)=38910, p<0.001; Fig. 4C). Both depolarization-induced rescue transients are comparable to wildtype (compare Fig. 2 and 4C). Transgenic rescue led to no significant differences in time to peak (control, 9.74 ± 1.34 sec, n=15; constitutive rescue, 9.21 ± 0.90 sec, n=22; conditional rescue, 7.31 ± 0.67 sec, n=25; F(2,59)=2.32, p=0.11, n.s.) or decay half-life (control t1/2, 19.94 ± 2.21 sec, r2=0.96 ± 0.01, n=14; constitutive rescue t1/2, 27.85 ± 3.63 sec, r2=0.96 ± 0.01, n=20; conditional rescue t1/2, 22.53 ± 2.55 sec, r2=0.95 ± 0.01, n=22; F(2,53)=2.273, p=0.19, n.s.). Thus, FMRP supplied only during the critical period completely rescues functional requirements to restore Ca2+ signaling properties.

To complement the wildtype rescue in mPN2 neurons, cell autonomous knockdown of dfmr1 was achieved with conditional transgenic RNA interference (RNAi). Animals were raised at the Gal80ts restrictive temperature (18°C) and then shifted to the restrictive temperature (29°C) at P4 to inactivate Gal80ts and induce dfmr1 RNAi (Fig. 4B). Three conditions are compared (Fig. 4D); 1) control with no RNAi or Gal80ts (R65G01-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; grey line), 2) constitutive dfmr1 RNAi (R65G01-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr1-RNAi, black line) and 3) conditional dfmr1 RNAi at P4 – 1 dpe (tubP-Gal80ts; R65G01-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr1-RNAi, red line). Compared to transgenic controls, constitutive and conditional critical period dfmr1 knockdown both resulted in highly significant increases in Ca2+ transient amplitude following acute K+ depolarization (control, 0.25 ± 0.05, n=16 neurons; constitutive RNAi, 0.33 ± 0.06, n=16 neurons, Dunnett, p<0.001; conditional RNAi, 0.35 ± 0.08, n=14 neurons; Dunnett, p<0.001; F(2,57)=5809, p<0.0001; Fig. 4D). Both knockdown strategies lead to greatly increased peak transient amplitude, thereby phenocopying 1 dpe dfmr1 null mPN2 neurons (compare to Fig. 2). In addition, both dfmr1 RNAi conditions led to substantial delays in time to peak (control, 5.89 ± 0.67 sec, n=16; constitutive RNAi, 8.94 ± 0.81 sec, n=14, Dunnett, p<0.05; conditional RNAi, 9.53 ± 1.14 sec, n=16, Dunnett, p<0.05; F(2,43)=5.083, p=0.01; Fig. 4D), although transient decay properties are similar across all groups (control t1/2, 22.95 ± 6.36 sec, r2=0.95 ± 0.02, n=7; constitutive RNAi t1/2, 26.41 ± 3.24 sec, r2=0.93 ± 0.02, n=16; conditional RNAi t1/2, 30.34 ± 5.08 sec, r2=0.95 ± 0.01, n=13; F(2,33)=0.5304, p=0.593). Taken together, these results show that temporally conditional and cell autonomous dfmr1 rescue/knockdown in mPN2 neurons within the FMRP-defined P4 – 1 dpe critical period accounts for the FMRP requirement in shaping Ca2+ transients, demonstrating a restricted FMRP developmental role.

Critical period dissection of FMRP function in inhibitory MBON-11 neurons

Conditional rescue and knockdown of dfmr1 in excitatory mPN2 neurons demonstrates a precise requirement for FMRP in Ca2+ signaling during the critical period. We performed parallel dfmr1 manipulations in inhibitory MBON-11 neurons to investigate the temporal requirement in these MB output cells. We first assayed constitutive vs. conditional critical period dfmr1 rescue (Fig. 4A). Compared to dfmr1 null mutants (dfmr150M, R12G04-Gal4>dfmr150M, UAS-GCamp5G; Fig. 4E, grey line), with a reduced Ca2+ transient peak amplitude at 1 dpe (0.52 ± 0.06, n=21 neurons), constitutive dfmr1 rescue (dfmr150M, R12G04-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr150M, UAS-9557-3; Fig. 4E, black line) led to a strong restoration of wildtype peak signaling (1.05 ± 0.03, n=23 neurons, Dunnett, p<0.001). Similarly, critical period induction of FMRP (tubP-Gal80ts; dfmr150M, R12G04-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr150M, UAS-9557-3; Fig. 4E, red line) led to a partial, yet highly significant restoration of peak Ca2+ amplitude in dfmr1 null neurons (0.69 ± 0.03, n=17 neurons, Dunnett, p<0.001; F(2,57)=40582, p<0.001). Although time to peak is comparable in all groups (dfmr1, 6.33 ± 0.44 sec, n=21; constitutive rescue, 5.88 ± 0.55 sec, p=0.53, n=23; conditional rescue, 6.06 ± 0.65 sec, p=0.72, n=17; F(2,49)=0.32, p=0.72, n.s.), both rescue conditions led to significant decreases in decay half-life (dfmr1 t1/2, 9.62 ± 0.83 sec, r2=0.93 ± 0.01, n=21; constitutive rescue t1/2, 7.33 ± 0.54 sec, r2=0.97 ± 0.01, n=22, Dunnett, p<0.05; conditional rescue t1/2, 6.74 ± 0.59 sec, r2=0.97 ± 0.01, n=16, Dunnett, p<0.05; F(2,56)=4.998, p=0.0101; Fig. 4E). Thus, dfmr1 rescue in inhibitory MBON-11 neurons remediates Ca2+ transient dysfunction, albeit with conditional rescue less robust than constitutive rescue, suggesting a broader temporal requirement in this GABAergic neuron class.

To complement rescue experiments, we again employed targeted conditional RNAi (Fig. 4B). Animals were raised at the Gal80ts restrictive temperature (18°C) and then shifted to the restrictive temperature (29°C) at P4 to inactivate Gal80ts and induce dfmr1 RNAi in MBON-11 neurons, with Ca2+ transients assayed at 1 dpe. Three conditions are compared (Fig. 4F): 1) transgenic control (R12G04-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; grey line), 2) constitutive dfmr1 RNAi (R12G04-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr1-RNAi, black line), and 3) conditional dfmr1 RNAi at the P4 – 1 dpe critical period (tubP-Gal80ts; R12G04-Gal4>UAS-GCamp5G; dfmr1-RNAi, red line). Conditional induction of dfmr1 RNAi during the critical period is highly effective in phenocopying the dfmr1 null mutant condition, and indeed results in a stronger effect than constitutive knockdown (Fig. 4F). Temporally targeted dfmr1 knockdown only in the P4 – 1 dpe critical period and only in MBON-11 neurons causes a dramatic decrease in peak Ca2+ transient amplitude (0.41 ± 0.09, n=10 neurons, Dunnett, p<0.001) compared to controls (1.05 ± 0.10, n=15 neurons; F(2,57)=40268, p<0.001; Fig. 4F). Constitutive dfmr1 knockdown of dfmr1 also causes a clear and significant reduction in peak Ca2+ transient amplitude (0.73 ± 0.09, n=21 neurons, Dunnett, p<0.001; Fig. 4F). We noted a slight difference in the relative time to peak Ca2+ influx in the conditional knockdown condition (control, 5.90 ± 0.83 sec, n=15 neurons; constitutive RNAi, 6.15 ± 0.64 sec, n=21, Dunnett, p>0.05; conditional RNAi, 9.44 ± 1.57 sec, n=10, Dunnett, p<0.05; F(2,43)=6.935, p=0.0025; Fig. 4F). Finally, decay half-life was not significantly different across all groups, despite a trend toward an extended decay in the conditional knockdown (control t1/2, 7.20 ± 0.79 sec, r2=0.97 ± 0.01, n=19; constitutive RNAi t1/2, 6.98 ± 0.72 sec, r2=0.95 ± 0.01, n=25; conditional RNAi t1/2, 10.13 ± 1.83 sec, r2=0.94 ± 0.01, n=14; F(2,51)=2.205, p=0.1199; Fig. 4F). Thus, conditional removal of FMRP during the critical period actually provides a more robust effect than constitutive loss in MBON-11 neurons, an effect that also occurs in mPN2 neurons. Taken together, these results indicate an essential and restricted FMRP requirement in shaping activity-induced Ca2+ transients, specifically during the early-use critical period window of development.

Optogenetic critical period stimulation alters FMRP-dependent Ca2+ transients

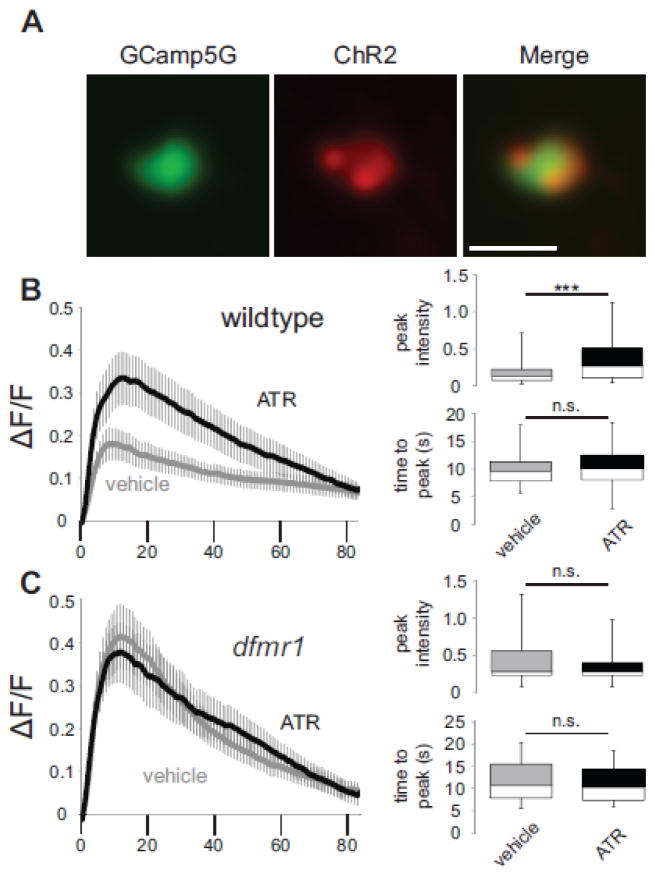

Previous work has revealed that FMRP is required for activity-dependent changes in MB circuit architecture and synaptic connectivity during the early-use critical period (Doll and Broadie, 2015; Tessier and Broadie, 2008). To test whether developmental activity induces changes in Ca2+ signaling dynamics, we co-expressed the depolarizing UAS-channelrhodopsin (ChR2) channel along with the UAS-GCamp5G [Ca2+] reporter in both excitatory input mPN2 and inhibitory output MBON-11 neurons, exposed newly-eclosed flies to a stimulating light paradigm (470 nm illumination of 20 ms pulses at 5 Hz for 24 hours) during the first day critical period following eclosion, and then performed fluorescent Ca2+ recordings as above. To assay mPN2 neurons, transgenic control (R65G01-Gal4>UAS-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry; UAS-GCamp5G) and dfmr1 null mutant (dfmr150M, R65G01-Gal4>UAS-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry; dfmr150M, UAS-GCamp5G) animals were raised on either EtOH vehicle or the essential ChR2 cofactor, all-trans retinal (ATR; Ataman et al., 2008; Schroll et al., 2006). ChR2 expression was verified (Fig. 5A, red) prior to GCamp5G reporter recording (Fig. 5A, green) in individually identified neurons. A summary of the results is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Critical period stimulation of mPN2 reveals FMRP-dependent Ca2+ dynamics. (A) Co-expression of UAS-GCamp5G Ca2+ reporter (green) and UAS-ChR2-H134R-mCherry optogenetic channel (red) driven by R65G01-Gal4 targeted to excitatory MB input mPN2 neurons. K+ depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients following 24 hours of blue light stimulation (5Hz, 20ms) in animals fed either vehicle alone or the all-trans retinal (ATR) essential cofactor for optogenetic stimulation in wildtype control (B) or dfmr1 null mutants (C). Left: Change of average fluorescence intensity over time ( F/F; mean±SEM). Right: Histograms (minimum, median, maximum and quartiles) depicting fluorescence peak intensity and time to peak fluorescence. WTvehicle n=17, WTATR n=18, dfmr1vehicle n=18, dfmr1ATR n=14. Statistical significance determined via unpaired, two-tailed t-tests indicated as ***p<0.001 or not significant (n.s.). Scale bar: 0.5μm.

Critical period stimulation of excitatory mPN2 neurons dramatically elevates Ca2+ peak amplitude above vehicle control neurons (WTvehicle, 0.18 ± 0.04, n=17 neurons; WTATR, 0.33 ± 0.06, n=18 neurons, t-test, p=9.20E-20; Fig. 5B). This amplitude change is not accompanied by a change in time to peak (WTvehicle, 9.88 ± 0.69 sec, n=17; WTATR, 10.43 ± 0.95 sec, n=18, t-test, p=0.65, n.s.) or decay half-life (WTvehicle t1/2, 43.99 ± 8.99 sec, r2=0.92 ± 0.02, n=11; WTATR t1/2, 40.49 ± 8.10 sec, r2=0.92 ± 0.04, n=18, t-test, p=0.78, n.s.). Importantly, this single cell-targeted stimulation during the critical period phenocopies Ca2+ transients in dfmr1 null mPN2 neurons at 1 dpe (compare to Fig. 2). Our previous work showed that dfmr1 null mPN2 neurons lack a morphological response to developmental optogenetic manipulations (Doll and Broadie, 2015). Consistently, critical period stimulation of dfmr1 null mPN2 neurons did not significantly affect depolarization-induced Ca2+ peak amplitude (dfmr1vehicle, 0.41 ± 0.08, n=18 neurons; dfmr1ATR, 0.38 ± 0.07, n=14 neurons, t-test, p=0.12, n.s.; Fig. 5C), time to peak (dfmr1vehicle, 11.55 ± 1.00 sec, n=18; dfmr1ATR, 10.92 ± 1.11 sec, n=14, t-test, p=0.68, n.s.) or half-life decay (dfmr1vehicle t1/2, 21.79 ± 2.7 sec, r2=0.95 ± 0.02, n=18; dfmr1ATR t1/2, 27.36 ± 5.72 sec, r2, 0.93 ± 0.03, n=13, t-test, p=0.35, n.s.). Thus, FMRP is absolutely required for activity-dependent developmental shifts in Ca2+ signaling dynamics, providing evidence that FMRP acts as an essential activity sensor during critical period development.

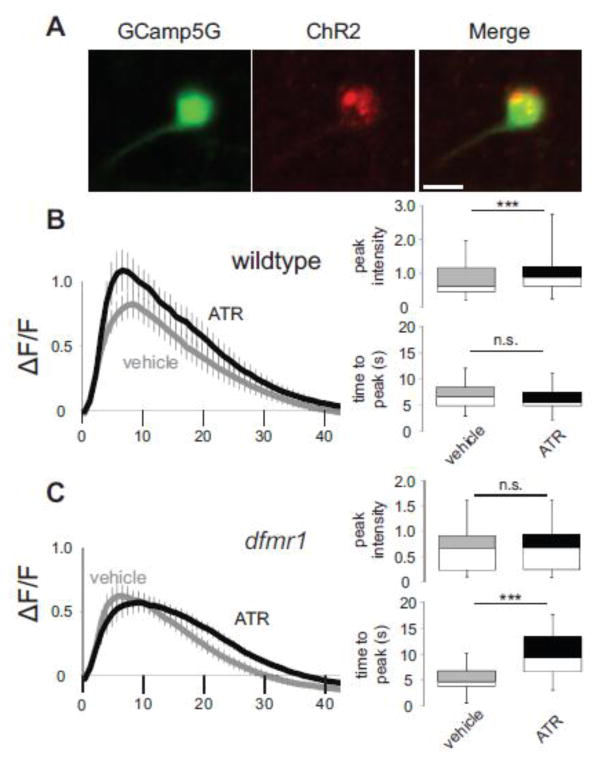

We next tested the activity-dependent requirements for FMRP in shaping critical period Ca2+ signaling in inhibitory MBON-11 neurons (Fig. 6). For MBON-11, the four experimental groups were wildtype control (R12G04-Gal4>UAS-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry; UAS-GCamp5G) and dfmr1 null (dfmr150M, R12G04-Gal4>UAS-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry; dfmr150M, UAS-GCamp5G) raised on EtOH vehicle or ATR-supplemented food. GCamp5G (Fig. 6A, green) and ChR2 (Fig. 6A, red) expression was verified in individual MBON-11 neurons. All four genotypes were exposed to 5 Hz blue light stimulation for 24 hours, with depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients assayed at the 1 dpe critical period (Fig. 6B,C). As in mPN2, stimulated MBON-11 neurons show a significant increase in peak Ca2+ transient amplitude (WTvehicle, 0.82 ± 0.11, n=20 neurons; WTATR, 1.09 ± 0.16, n=19 neurons, t-test, p=7.58E-10; Fig. 6B), with no impact on time to peak (WTvehicle, 6.70 ± 0.52 sec, n=20; WTATR, 6.22 ± 0.49 sec, n=19, t-test, p=0.51, n.s.; Fig. 6B) or decay half-life (WTvehicle t1/2, 7.36 ± 0.49 sec, r2=0.97 ± 0.01, n=20; WTATR t1/2, 8.44 ± 0.97 sec, r2=0.95 ± 0.01, n=19, t-test, p=0.32, n.s.). In sharp contrast, dfmr1 null neurons are not susceptible to developmental activity modulation (compare Figs. 6B and 6C), as dfmr1 mutants do not exhibit any activity-dependent increase in Ca2+ peak amplitude (dfmr1vehicle, 0.62 ± 0.09, n=21 neurons; dfmr1ATR, 0.57 ± 0.08, n=15 neurons, t-test, p=0.098; Fig. 6C) or decay half-life (dfmr1vehicle t1/2, 6.27 ± 0.37 sec, r2=0.94 ± 0.01, n=21; dfmr1ATR t1/2, 6.64±0.56 sec, r2=0.97±0.01, n=15, t-test, p=0.57; Fig. 6C). However, there is an increase in time to peak (dfmr1vehicle, 5.20 ± 0.51 sec, n=21; dfmr1ATR t1/2, 10.02 ± 1.26 sec, n=15, t-test, p=0.00036; Fig. 6C), an effect unique to this experimental paradigm. Thus, activity-dependent changes in Ca2+ signaling are again absent in dfmr1 null neurons, although we cannot rule out a stimulation-induced effect on broader timescale Ca2+ transients in dfmr1 null MBON-11 neurons. Taken together, critical period stimulation of both neuron classes increases Ca2+ signals following depolarization, and this developmental change is completely dependent on FMRP.

Figure 6.

Critical period MBON-11 stimulation shows FMRP-dependent Ca2+ dynamics. (A) Dual expression of the UAS-GCamp5G Ca2+ reporter (green) and the UAS-ChR2-H134R-mCherry optogenetic channel (red) under control of the R12G04-Gal4 driver selectively targeted to inhibitory output MBON-11 neurons. K+ depolarization-induced Ca2+ transients following 24 hours of blue light stimulation (5Hz, 20ms) in animals fed either vehicle or all-trans retinal (ATR) for optogenetic stimulation in wildtype control (B) and dfmr1 null mutants (C). The change of average fluorescence intensity (mean±SEM) following acute K+ depolarization is shown on the left, with histograms on the right depicting the GCamp5G Ca2+ reporter fluorescence peak intensity and time to peak (minimum, median, maximum and quartiles). WTvehicle n=20, WTATR n=19, dfmr1vehicle n=21, dfmr1ATR n=15. Statistical significance determined via unpaired, two-tailed t-tests indicated as ***p<0.001 or not significant (n.s.). Scale bar: 10μm.

Discussion

Neuron type-specific FMRP critical period requirements

The question of whether Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a neurodevelopmental disease, a disease of continuous neural plasticity dysfunction, or some combination, is a question of paramount importance in designing effective disease interventions. The determination requires precise methods to dissect temporal requirements within defined neural circuitry. This study employs precisely-targeted transgenic drivers (Jenett et al., 2012) to introduce a [Ca2+] reporter (GCamp5G) (Akerboom et al., 2012; Kirkhart and Scott, 2015) and optogenetic channelrhodopsin (ChR2) (Dani et al., 2014) into individually-identified excitatory input and inhibitory output neurons in the well-mapped MB learning/memory circuit (Tanaka et al., 2012; Tanaka et al., 2008). We previously discovered an early-use MB critical period defined by peak FMRP expression, in which FMRP loss prevents detection of sensory activity that shapes synaptic connectivity (Tessier and Broadie, 2008). More recently, we discovered excitatory input (mPN2) and inhibitory output (MBON-11) neurons display activity-dependent bidirectional responses to depolarizing and hyperpolarizing optogenetic manipulation, only within the FMRP-defined critical period and wholly dependent on FMRP, shaping synaptic connectivity (Doll and Broadie, 2015). We show here that FMRP bidirectionally regulates critical period calcium signaling in these two neuron classes: excitatory input neurons exhibit elevated depolarization-induced transients and inhibitory output neurons display reduced transients in dfmr1 mutants. These results reveal a novel critical period-specific mechanism supporting the E:I imbalance hypothesis of FXS (Gatto et al., 2014).

It is well established that neural circuit optimization occurs via activity-dependent changes during restricted early-use temporal windows (Hensch, 2004; Holtmaat and Svoboda, 2009). A rich history of altered neural architecture in FXS (Irwin et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001), and recent functional dissections demonstrate that structural defects are coupled with changes in neural excitability (Brager and Johnston, 2014). Importantly, mouse FXS models have also revealed essential roles for FMRP during critical period functional development. These include a pronounced developmental delay in excitatory somatosensory cortex (Harlow et al., 2010; Till et al., 2012), delayed depolarization-to-hyperpolarization switch in GABAergic transmission (He et al., 2014), and critical period-specific neural circuit hyperexcitation (Goncalves et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). These pioneering studies of critical period refinement have provided the baseline for understanding the impact of FMRP on critical period neural circuit functional refinement, particularly in establishing and maintaining the proper excitatory-inhibitory balance (Contractor et al., 2015; Meredith, 2015).

In the Drosophila MB circuit, FMRP suppresses calcium signaling in excitatory input mPN2 neurons, but enhances calcium signaling in inhibitory output MBON-11 neurons (compare Figures 2 and 3). These opposing roles for FMRP occur in starkly contrasting neuron classes: excitatory cholinergic projection neurons carry olfactory sensory input (Iniguez et al., 2013), and inhibitory GABAergic MBON-11 neurons (Aso et al., 2014a) maintain aversive memory for both olfactory and visual modalities (Aso et al., 2014b). Importantly, FXS has been characterized as a disease of E:I imbalance, with increased excitation and decreased inhibition (Gibson et al., 2008). This study provides additional evidence supporting this theory, with opposite calcium signaling defects in individually-identified excitatory vs. inhibitory neurons within the same learning/memory circuit. Although we cannot rule out a maintained role for FMRP at maturity, the defects in both neuron classes are far more pronounced during the critical period of initial sensory input. Most strikingly, both dfmr1 null neuron classes fail to undergo the dramatic developmental changes in calcium signaling that occur in wildtype animals. Conditional dfmr1 manipulations (cell autonomous rescue and RNAi) confirm the critical period specific FMRP requirement. However, we were surprised to find more robust dfmr1 knockdown effects within this transient period, compared to constitutive dfmr1 knockdown in both neuron classes. This may suggest that constitutive knockdown generates nonspecific effects, such as compensation due to RNAi expression in these neurons throughout development. Conditional critical period dfmr1 rescue provides a nearly complete restoration of calcium signaling in excitatory mPN2 neurons, but only a partial remediation of dfmr1 defects in inhibitory MBON-11 neurons. This may suggest that inhibitory neurons require a broader period of FMRP function during development, which may not be surprising given the persistent reduction in inhibitory signaling in this FXS disease model (Gatto et al., 2014).

FMRP control of calcium signaling during the critical period

How and why might FMRP mediate calcium signaling downstream of activity during critical period development? As an essential component of neuronal excitability, calcium influx and subsequent regulation represents a prime target for FMRP function (Tessier and Broadie, 2012). We postulate that impaired critical period calcium regulation may underlie formation of the inappropriate neural architecture and synaptic connectivity characterizing the FXS disease state (Lohmann, 2009; Tessier and Broadie, 2008; Tessier and Broadie, 2011). These functional defects may be rooted in defects in calcium buffering capacity caused by the loss of calcium-binding proteins (e.g. calmodulin and calbindin) in dfmr1 null mutants (Tessier and Broadie, 2011). Consistently, mutations in calmodulin and calbindin lead to altered calcium transients in multiple neuronal contexts (Arredondo et al., 1998; Barski et al., 2003). It is also possible that FMRP differentially regulates calcium release from intracellular stores in a neuron type-specific manner (Tessier and Broadie, 2011). Depolarization-dependent calcium influx can occur from the outside, from calcium store organelles within the neuron, or from a combination of both, and we have previously established that FMRP is involved in calcium mobilization from both pathways in Drosophila brain MB neurons (Tessier and Broadie, 2011). Importantly, calcium can regulate the structural (Lohmann et al., 2005; Lohmann and Wong, 2005) and functional (Lisman et al., 2002) adaptations necessary for synaptic specificity, and defective calcium signaling may underlie multiple autism phenotypes (Krey and Dolmetsch, 2007).

The direct binding and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ and K+ channels by FMRP represents an intriguing mechanism for the developmental maturation of circuits. A proper developmental analysis would need to include a temporal survey of channel expression in the FXS disease state, as well as roles for direct binding of FMRP to multiple classes of voltage-gated channels. For example, FMRP is capable of regulating both expression and degradation of CaV2.2 channels (Ferron et al., 2014), thereby providing both direct and indirect regulatory roles. Interestingly, Ca2+ channels and sensors undergo strong developmental shifts in expression and spatial organization, for example in the calyx of Held (Fedchyshyn and Wang, 2005), including developmental alterations in the type of channels expressed following initial sensory onset (Alamilla and Gillespie, 2013). Likewise, the density of presynaptic K+ channels increases during late brain development, which correlates with shorter action potential duration (Nakamura and Takahashi, 2007). FMRP has been shown to maintain activity-dependent tonotopic KV3.1b expression gradients, with FMRP loss causing flattened tonotopicity and reduced K+ currents (Strumbos et al., 2010). Importantly, FMRP directly binds Na+-gated KCNT1 and Ca2+-gated BK K+ channel classes, which serve to repolarize the membrane following activity (Bean, 2007; Brown et al., 2010; Deng et al., 2013; Kim and Kaczmarek, 2014). The use of targeted dfmr1 mutations to dissect RNA-binding translational regulation and channel-binding FMRP properties may allow us to begin to dissect these potential developmental mechanisms. For example, the newly described dfmr1 R138Q mutation disrupts BK channel binding without affecting translational repressive roles (Myrick et al., 2015). With such an array of regulatory capacities, FMRP modulation of channel expression and function will need to be explored both in the context of activity initiation through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and activity termination via voltage-gated K+ channels, both of which could contribute to calcium signaling defects in the FXS disease state.

Optogenetic manipulations support FXS hyperexcitation theory

Combining optogenetic manipulation with precisely targeted neuron-specific transgenic drivers provides exciting new opportunities in developmental neuroscience (Honjo et al., 2012; Klapoetke et al., 2014). Use of these tools in the well-mapped Drosophila MB circuit is a particularly potent method to study activity-dependent neural development, especially to dissect cell autonomous requirements. Wildtype neurons respond to optogenetic stimulation during critical period development by strongly altering calcium signaling dynamics, but activity-dependent modulation is completely absent in dfmr1 null neurons. Single cell-targeted stimulation during the critical period leads to increased depolarization-induced calcium signaling, providing evidence of an activity-dependent alteration in functional properties and an exciting proof-of-principle of the hyperexcitation theory of FXS (Bear et al., 2004; Goncalves et al., 2013). Of particular interest, critical period stimulation of wildtype excitatory mPN2 neurons generates depolarization-dependent calcium dynamics strikingly reminiscent of dfmr1 null neurons, providing a specific illustration of the hyperexcitation theory of FXS (Gibson et al., 2008; Goncalves et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014). As projection neurons receive excitatory input from odorant receptor neurons (ORNs) in the antennal lobe (Vosshall and Stocker, 2007), this optogenetic hyper-excitation mimics exaggerated olfactory sensory input during circuit development. Thus, neurons are mis-tuned to inappropriate sensory input during the plasticity permissive critical period, resulting in calcium signaling impairments that closely mimic the FXS disease state.

Inhibitory GABAergic MBON-11 neurons also respond to heightened critical period stimulation with increased calcium signaling, demonstrating a similar activity-dependent response across neuron classes. However, this phenotype is specific to activity-manipulated wildtype neurons and does not phenocopy the dfmr1 null condition. This suggests that inhibitory MBON-11 neurons may not be exposed to developmental hyperexcitation in the FXS condition, as predicted for mPN2. MBON-11 neurons receive input from MB Kenyon Cell neurons (Aso et al., 2014a), but the neurotransmission mechanism remains elusive (Henry et al., 2012), despite an established essential role in aversive memory formation (Aso et al., 2014b). Since FMRP regulates calcium dynamics in an opposite direction in this inhibitory neuron type, the hyperexcitation theory of FXS likely does not fully encompass the disease condition, which also includes hypo-inhibition as a prominent component. FMRP is known to regulate GABAergic components, in both Drosophila and mammals (Gatto et al., 2014; Lozano et al., 2014), and this likely provides a distinct FMRP regulatory mechanism on either end of the emerging E:I balance in the developing brain (Cea-Del Rio and Huntsman, 2014; Gibson et al., 2008). Unfortunately, the lack of activity response in dfmr1 null neurons may limit our ability to use exogenous activity modulation to dissect morphology and function. However, dfmr1 mutant neurons may display shifted critical periods (Harlow et al., 2010), and both the studied neuron classes possess calcium signaling dynamics that are much more similar to wildtype at maturity. With the application of more advanced optogenetics techniques, such as CsChrimson (Klapoetke et al., 2014), ChR2-XXL (Dawydow et al., 2014) and red-shifted chloride inhibitors like Jaws (Chuong et al., 2014), we may be able to more effectively dissect structural and functional components of developing and mature circuits.

Conclusions

This study contributes key new insights to our understanding of the FMRP requirements in activity-dependent critical period neural circuit refinement. The powerful Drosophila genetic toolkit has allowed us for the first time to define both neuron-specific and temporal-specific FMRP requirements in depolarization calcium signaling dynamics. The key results are 1) excitatory and inhibitory neurons are misregulated in opposite directions in the absence of FMRP, and 2) there is a restricted FMRP requirement during the early-use critical period. In the FXS disease state, excitatory (E) neurons exhibit elevated activity-dependent calcium transients and inhibitory (I) output neurons display suppressed transients, supporting the E:I imbalance hypothesis of FXS. Moreover, restricted critical period stimulation increases calcium transients in wildtype, and this developmental refinement depends absolutely on FMRP. Single cell-targeted optogenetic stimulation and FMRP conditional manipulations establish cell-autonomous critical period functional refinement mechanisms within individually identified single excitatory and inhibitory neurons within a common learning/memory circuit. Future use of targeted human patient FMRP point mutations will allow us to dissect the roles of RNA-binding translational regulation and channel-binding activity regulation in the control of these critical period developmental mechanisms.

Highlights.

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the leading heritable cause of autism spectrum disorders

Imbalance between excitation (E) and inhibition (I) common in autistic brain circuits

Opposite activity-dependent Ca2+ signaling defects in E vs. I neurons in a FXS model

FXS Ca2+ signaling defects specific to the early-use critical period of development

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful for the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Indiana University), which provided essential genetic stocks used in this study. We particularly thank Leslie Griffith (Brandeis University) for the UAS-ChR2(H134R)-mCherry optogenetic line used in this study. We also thank Jenny Aguilar and Cheryl Gatto for intellectual input on this study. This work was fully supported by NIH grant R01 MH084989 to K.B.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions: C.A.D. and K.B. conceived and designed the experiments. C.A.D. performed all experiments and analyzed all data. C.A.D. and K.B. co-wrote the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akerboom J, et al. Optimization of a GCaMP calcium indicator for neural activity imaging. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13819–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamilla J, Gillespie DC. Maturation of calcium-dependent GABA, glycine, and glutamate release in the glycinergic MNTB-LSO pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo L, et al. Increased transmitter release and aberrant synapse morphology in a Drosophila calmodulin mutant. Genetics. 1998;150:265–74. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso Y, et al. The neuronal architecture of the mushroom body provides a logic for associative learning. Elife. 2014a;3:e04577. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aso Y, et al. Mushroom body output neurons encode valence and guide memory-based action selection in Drosophila. Elife. 2014b;3:e04580. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ataman B, et al. Rapid activity-dependent modifications in synaptic structure and function require bidirectional Wnt signaling. Neuron. 2008;57:705–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski JJ, et al. Calbindin in cerebellar Purkinje cells is a critical determinant of the precision of motor coordination. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3469–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03469.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:451–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear MF, et al. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:370–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm RA, et al. A genetic mosaic approach for neural circuit mapping in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:16378–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004669107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle L, Kaufmann WE. The behavioral phenotype of FMR1 mutations. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2010;154C:469–76. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brager DH, Johnston D. Channelopathies and dendritic dysfunction in fragile X syndrome. Brain Res Bull. 2014;103:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls gating of the sodium-activated potassium channel Slack. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:819–21. doi: 10.1038/nn.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cea-Del Rio CA, Huntsman MM. The contribution of inhibitory interneurons to circuit dysfunction in Fragile X Syndrome. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:245. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, et al. The fragile X mental retardation protein binds and regulates a novel class of mRNAs containing U rich target sequences. Neuroscience. 2003;120:1005–17. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong AS, et al. Noninvasive optical inhibition with a red-shifted microbial rhodopsin. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1123–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor A, et al. Altered Neuronal and Circuit Excitability in Fragile X Syndrome. Neuron. 2015;87:699–715. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani N, et al. Two protein N-acetylgalactosaminyl transferases regulate synaptic plasticity by activity-dependent regulation of integrin signaling. J Neurosci. 2014;34:13047–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1484-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawydow A, et al. Channelrhodopsin-2-XXL, a powerful optogenetic tool for low-light applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13972–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408269111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng PY, et al. FMRP regulates neurotransmitter release and synaptic information transmission by modulating action potential duration via BK channels. Neuron. 2013;77:696–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng PY, et al. Abnormal presynaptic short-term plasticity and information processing in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10971–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2021-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll CA, Broadie K. Impaired activity-dependent neural circuit assembly and refinement in autism spectrum disorder genetic models. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2014;8 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll CA, Broadie K. Activity-dependent FMRP requirements in development of the neural circuitry of learning and memory. Development. 2015;142:1346–56. doi: 10.1242/dev.117127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn MJ, Wang LY. Developmental transformation of the release modality at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4131–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0350-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron L, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls synaptic vesicle exocytosis by modulating N-type calcium channel density. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3628. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala A, Spall T. In vivo calcium imaging of brain activity in Drosophila by transgenic cameleon expression. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:PL6. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.174.pl6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fore TR, et al. Mapping and application of enhancer-trap flippase expression in larval and adult Drosophila CNS. J Vis Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frickenhaus M, et al. Highly efficient cell-type-specific gene inactivation reveals a key function for the Drosophila FUS homolog cabeza in neurons. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9107. doi: 10.1038/srep09107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto CL, Broadie K. Temporal requirements of the fragile X mental retardation protein in the regulation of synaptic structure. Development. 2008;135:2637–48. doi: 10.1242/dev.022244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto CL, Broadie K. The fragile X mental retardation protein in circadian rhythmicity and memory consolidation. Mol Neurobiol. 2009;39:107–29. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto CL, Broadie K. Genetic controls balancing excitatory and inhibitory synaptogenesis in neurodevelopmental disorder models. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2010;2:4. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto CL, et al. GABAergic circuit dysfunction in the Drosophila Fragile X syndrome model. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;65:142–59. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson JR, et al. Imbalance of neocortical excitation and inhibition and altered UP states reflect network hyperexcitability in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2615–26. doi: 10.1152/jn.90752.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves JT, et al. Circuit level defects in the developing neocortex of Fragile X mice. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:903–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein regulates protein expression and mRNA translation of the potassium channel Kv4.2. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5693–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6661-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow EG, et al. Critical period plasticity is disrupted in the barrel cortex of FMR1 knockout mice. Neuron. 2010;65:385–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, et al. The developmental switch in GABA polarity is delayed in fragile X mice. J Neurosci. 2014;34:446–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4447-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry GL, et al. Cell type-specific genomics of Drosophila neurons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9691–704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. Critical period regulation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:549–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera SC, et al. Tissue homeostasis in the wing disc of Drosophila melanogaster: immediate response to massive damage during development. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat A, Svoboda K. Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:647–58. doi: 10.1038/nrn2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo K, et al. Optogenetic manipulation of neural circuits and behavior in Drosophila larvae. Nature protocols. 2012;7:1470–1478. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniguez J, et al. Cav3-type alpha1T calcium channels mediate transient calcium currents that regulate repetitive firing in Drosophila antennal lobe PNs. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110:1490–6. doi: 10.1152/jn.00368.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin SA, et al. Abnormal dendritic spine characteristics in the temporal and visual cortices of patients with fragile-X syndrome: a quantitative examination. Am J Med Genet. 2001;98:161–7. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010115)98:2<161::aid-ajmg1025>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, et al. A systematic nomenclature for the insect brain. Neuron. 2014;81:755–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenett A, et al. A GAL4-driver line resource for Drosophila neurobiology. Cell Rep. 2012;2:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeser PS, Regehr WG. Molecular mechanisms for synchronous, asynchronous, and spontaneous neurotransmitter release. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:333–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GE, Kaczmarek LK. Emerging role of the KCNT1 Slack channel in intellectual disability. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:209. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkhart C, Scott K. Gustatory learning and processing in the Drosophila mushroom bodies. J Neurosci. 2015;35:5950–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3930-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapoetke NC, et al. Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat Methods. 2014;11:338–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krey JF, Dolmetsch RE. Molecular mechanisms of autism: a possible role for Ca2+ signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, et al. Bidirectional regulation of dendritic voltage-gated potassium channels by the fragile X mental retardation protein. Neuron. 2011;72:630–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J, et al. The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioural memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:175–90. doi: 10.1038/nrn753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, et al. Serotonin and insulin-like peptides modulate leucokinin-producing neurons that affect feeding and water homeostasis in Drosophila. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:1840–63. doi: 10.1002/cne.23768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann C. Calcium signaling and the development of specific neuronal connections. Prog Brain Res. 2009;175:443–52. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17529-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann C, et al. Local calcium transients regulate the spontaneous motility of dendritic filopodia. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:305–12. doi: 10.1038/nn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann C, Wong RO. Regulation of dendritic growth and plasticity by local and global calcium dynamics. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R, et al. Modulation of the GABAergic pathway for the treatment of fragile X syndrome. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1769–79. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S42919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, et al. Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science. 2003;302:1765–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1089035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith RM. Sensitive and critical periods during neurotypical and aberrant neurodevelopment: a framework for neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;50:180–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick LK, et al. Independent role for presynaptic FMRP revealed by an FMR1 missense mutation associated with intellectual disability and seizures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:949–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423094112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Takahashi T. Developmental changes in potassium currents at the rat calyx of Held presynaptic terminal. J Physiol. 2007;581:1101–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng FS, Jackson FR. The ROP vesicle release factor is required in adult Drosophila glia for normal circadian behavior. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:256. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, et al. The Drosophila fragile X gene negatively regulates neuronal elaboration and synaptic differentiation. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1863–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AB, et al. A target cell-specific role for presynaptic Fmr1 in regulating glutamate release onto neocortical fast-spiking inhibitory neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:2593–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2447-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portera-Cailliau C. Which comes first in fragile X syndrome, dendritic spine dysgenesis or defects in circuit plasticity? Neuroscientist. 2012;18:28–44. doi: 10.1177/1073858410395322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulver SR, et al. Temporal dynamics of neuronal activation by Channelrhodopsin-2 and TRPA1 determine behavioral output in Drosophila larvae. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:3075–88. doi: 10.1152/jn.00071.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repicky S, Broadie K. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated use-dependent down-regulation of synaptic excitability involves the fragile X mental retardation protein. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:672–87. doi: 10.1152/jn.90953.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, et al. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroll C, et al. Light-induced activation of distinct modulatory neurons triggers appetitive or aversive learning in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1741–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strumbos JG, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein is required for rapid experience-dependent regulation of the potassium channel Kv3.1b. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10263–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1125-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka NK, et al. Organization of antennal lobe-associated neurons in adult Drosophila melanogaster brain. J Comp Neurol. 2012;520:4067–130. doi: 10.1002/cne.23142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka NK, et al. Neuronal assemblies of the Drosophila mushroom body. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:711–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.21692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier CR, Broadie K. Drosophila fragile X mental retardation protein developmentally regulates activity-dependent axon pruning. Development. 2008;135:1547–57. doi: 10.1242/dev.015867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier CR, Broadie K. The fragile X mental retardation protein developmentally regulates the strength and fidelity of calcium signaling in Drosophila mushroom body neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:147–59. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessier CR, Broadie K. Molecular and genetic analysis of the Drosophila model of fragile X syndrome. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2012;54:119–56. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-21649-7_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till SM, et al. Altered maturation of the primary somatosensory cortex in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2143–56. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomchik SM, Davis RL. Dynamics of learning-related cAMP signaling and stimulus integration in the Drosophila olfactory pathway. Neuron. 2009;64:510–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutor AS, et al. Src64B phosphorylates Dumbfounded and regulates slit diaphragm dynamics: Drosophila as a model to study nephropathies. Development. 2014;141:367–76. doi: 10.1242/dev.099408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosshall LB, Stocker RF. Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:505–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV links group I metabotropic glutamate receptors to fragile X mental retardation protein in cingulate cortex. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18953–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, et al. New perspectives on the biology of fragile X syndrome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:256–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz ED, et al. Deciphering discord: How Drosophila research has enhanced our understanding of the importance of FMRP in different spatial and temporal contexts. Exp Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, et al. Dendritic channelopathies contribute to neocortical and sensory hyperexcitability in Fmr1(-/y) mice. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1701–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, et al. Regulation of neuronal excitability by interaction of fragile X mental retardation protein with slack potassium channels. J Neurosci. 2012;32:15318–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2162-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, et al. Drosophila fragile X-related gene regulates the MAP1B homolog Futsch to control synaptic structure and function. Cell. 2001;107:591–603. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00589-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]