Abstract

Background

Provider biases and negative attitudes are recognized barriers to optimal pain management in sickle cell disease, particularly in the emergency department (ED).

Measures

This prospective cohort measures pre- and post-intervention provider attitudes towards patients with sickle pain crises using a validated survey instrument.

Intervention

ED providers viewed an eight-minute online video that illustrated challenges in sickle cell pain management, perspectives of patients and providers as well as misconceptions and stereotypes of which to be wary.

Outcomes

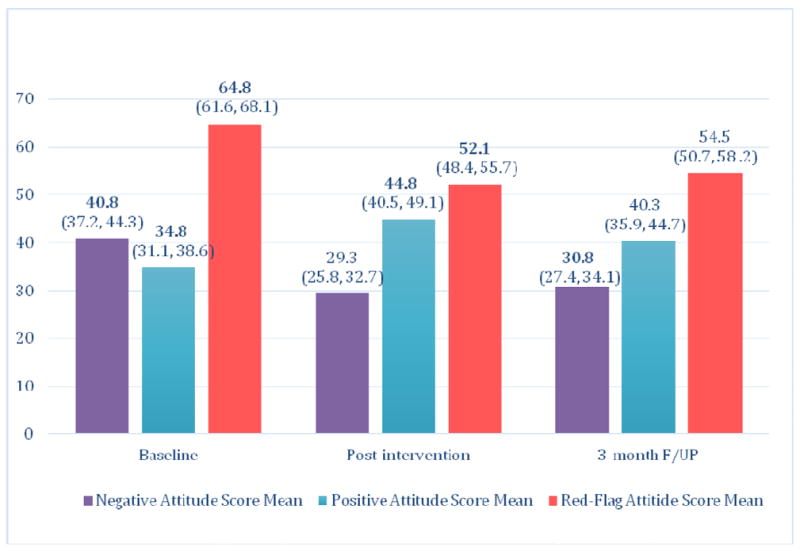

Ninety-six ED providers were enrolled. Negative attitude scoring decreased, with a mean difference -11.5 from baseline, and positive attitudes improved, with a mean difference +10. Endorsement of red-flag behaviors similarly decreased (mean difference -12.8). Results were statistically significant and sustained on repeat testing three months post-intervention.

Conclusions/Lessons Learned

Brief video-based educational interventions can improve emergency provider attitudes towards patients with sickle pain crises, potentially curtailing pain crises early, improving health outcomes and patient satisfaction scores.

Keywords: Sickle cell, pain crises, provider attitudes, video intervention

Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited blood disorder that effects millions worldwide, including an estimated 100,000 Americans. In the U.S., SCD results in over 200,000 emergency department (ED) visits annually, with pain as the most common complaint (1). In addition to being excruciating, incapacitating, and sometimes refractory to even the most advanced analgesic regimens, there are numerous challenges to providing optimal pain management to SCD patients, especially in the acute care setting. Under-medication has been identified as a common problem encountered by many patients seeking care for pain in emergency departments (2). The quality of care provided in the ED also can be negatively affected by a number of factors, including pressures that result from high patient turnover, long wait times, and lack of continuity of care.

The complexity of pain mechanisms and severity of SCD create additional provider bias. Behaviors exhibited by patients with SCD seeking care for severe pain in ED settings often do not match behavioral cues (e.g., moaning or crying). This apparent lack of concordance between observed and presumed patient behavioral cues can lead to provider skepticism about the veracity of the SCD patient’s report of pain. Furthermore, as SCD patients often require opioids for disabling chronic pain, many develop opioid tolerance. Requirement of higher doses and requests for particular treatment regimens that are most effective for them can lead health professionals to perceive this as “drug-seeking behavior.” These suspicions are potentially exacerbated by the fact that the disease primarily affects young African Americans, a group that is already perceived by clinicians to have higher rates of substance abuse (3). Clinician characteristics also may affect attitudes. Compared to hematologists, surveys found ED providers to have more negative attitudes towards SCD patients (4). Besides, the study shows that ED providers with the highest levels of negative attitudes towards SCD patients were less amenable to adhering to recommended pain management strategies (5). Not surprisingly, several studies have shown that the majority of SCD patients rated their ED experience as “very poor,” demonstrating a need for improvement in the care of SCD patients in the ED (6). These knowledge gaps, prejudices, negative attitudes, and the suboptimal pain management perpetuate a cycle of SCD patient-provider mistrust and dissatisfaction.

Prior approaches directed towards improving the management of acute SCD pain include provider education, establishment of algorithmic pain management protocols, and the creation of dedicated day hospitals for patients with SCD (7, 8). These may not be viable options for many community hospitals because of a lack of resources, structure, or personnel required.

Haywood et al. demonstrated improved attitudes among internists and nurses after a short video-based intervention about SCD patients (9). However, there have been no studies to date that focused on similar interventions in the ED, where patients with sickle cell pain crises most often present.

Measures

Our study was conducted at a large, urban, inner city academic emergency department and utilized a single-group pretest/multiple-posttest design. Eligible participants were health care providers including attending physicians, residents, midlevels (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) and nurses clinically practicing at the institution’s adult ED as of December 2013. The Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Using the previously validated General Perceptions About Sickle Cell Patients Scale (5, 9) (Appendix I, available at jpsmjournal.com), the primary outcomes measured were provider attitudes towards SCD patients. Subscale measures included 1) the six-item negative attitudes subscale (in which higher scores indicate more negative views about SCD patients), 2) the four-item positive attitudes subscale (in which higher scores indicate more positive feelings of affiliation towards SCD patients), and 3) the five-item red-flag behaviors subscale (in which higher scores indicate greater endorsement of the belief that certain SCD patient behaviors raise the clinician’s concern about patient drug-seeking, e.g., requesting specific narcotics, changing behavior when provider walk in) (5). We also collected information on potentially confounding provider characteristics, including age, sex, type of provider (nurse, attending, physician assistant or resident) and years of clinical experience.

Simple and multivariable generalized estimating equation (GEE) analyses were used to identify impact (immediate or long-term) of our intervention on attitudes compared to baseline. Both unadjusted and adjusted attitudes for potentially confounding ED provider characteristics were reviewed. One-way ANOVAs and t-tests were utilized for bivariate analyses, and GEE models in multivariable analyses accounting for any potentially confounding provider characteristic effects. Two-sided P-values at a level of <0.05 were used to assess statistical significance. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 13.0 ® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Intervention

We created an eight-minute video featuring adult SCD patients and ED providers in conjunction with the Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) Digital Media Group, which discusses, from both the ED provider’s and patient’s perspective, challenges in ED care for patients with SCD pain. Misinformation, stereotypes, and biases often held by ED providers towards the SCD population were critically examined and reviewed by the patients and providers. Accurate data about the actual experiences and characteristics of SCD patients were provided. All themes, challenges, and data discussed in the film were critically evaluated for their veracity by the SCD research panel (co-authors), comprising ED providers, a hematologist specializing in SCD, patient representatives from the adult SCD community, and bioethicists who study the SCD population.

Every provider in the institution’s adult ED was invited to complete the baseline survey during a departmental meeting. An internet link to the anonymous baseline survey on Survey Monkey was sent out via email to all ED providers – attending physicians, residents, midlevels, and nurses. Participants were enrolled in the study and assigned a study ID upon completion of the initial survey. Names were not collected to maintain anonymity and only email addresses were used to link the three surveys, which were accessible only by the study coordinator. All data analysis was done using the unique study ID. Attempts were made to blind study subjects to the research hypothesis by not including language related to provider attitudes or perceptions. Participants were asked to help us understand some of the challenges of managing sickle cell crisis in the ED by participating in our survey-based study. We referred to our video as a “video on SCD and its management in the ED.” The link to the video was sent via email. Those agreeing to participate completed a pretest, which consisted of an initial online survey of their attitudes towards SCD patients. One week after the pretest survey, study participants were asked to view the eight-minute SCD video intervention online. A link to the video was sent by email and although not proctored, it is presumed to have been viewed by the study participant accessing it through their email inbox. Participants were re-assessed on the attitudinal survey immediately after viewing the video (posttest 1). Three months later, participant attitudes were reassessed (posttest 2).

Outcomes

A total of 96 subjects were enrolled – 51% of all eligible ED health care providers (Table 1). All 96 participants completed the initial survey. Of these, 83 completed the second survey. Of the 83 that completed the post-video survey, 80 completed the final three-month post-intervention survey (83.3% completion rate from initial to final survey). Of the 96 participants, 57% were nurses, 10% were attending physicians and the remaining were residents and midlevel providers. Seventy-two percent were female and 44% were between the ages of 30 and 39 years. Forty-one percent of participants reported two to four years of clinical experience.

Table 1. Health Care Provider Characteristics at Baseline (n = 96).

| Clinician Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20-29 | 33 (34%) |

| 30-39 | 42 (44%) |

| 40-49 | 13 (14%) |

| 50-59 | 5 (5%) |

| 60-69 | 3 (3%) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 27 (28%) |

| Female | 69 (72%) |

| Clinical Role | |

| Physician | 10 (10%) |

| Resident | 24 (25%) |

| Midlevel | 7 (7%) |

| Nurse | 55 (57%) |

| Experience (in yrs) | |

| 0-1 | 19 (20%) |

| 2-4 | 39 (41%) |

| 5-9 | 15 (16%) |

| 10-14 | 5 (5%) |

| 15-19 | 10 (10%) |

| 20+ | 8 (8%) |

Bivariate analyses examining mean scores on the provider attitude subscales of interest at baseline, immediately post-intervention, and three months after the intervention, are shown in Fig. 1. Scores were normally distributed and scores on each of the attitudinal measures significantly improved in comparison to baseline scores immediately post-intervention, and again at three months post-intervention. Mean score on the negative attitudes subscale decreased compared to pre-intervention baseline from a score of 40.8 to 29.3, a difference of -11.5 (95% confidence interval [CI] -14.3, -8.7). The mean score on the positive attitudes subscale increased compared to baseline from 34.8 to 44.8, with a mean difference -10 points (95% CI 6.6, 13.4). Red-flag behaviors subscale decreased from 64.8 to 52.1, with a mean difference of -12.8 (95% CI -16.3, -9.3). The differences between scores after three months of follow-up compared to baseline were all statistically significant and similar in magnitude to the differences found immediately post-intervention. Attitudinal scores at three month follow-up were not statistically different than the immediate post-intervention scores for two of the three subscales. Scores on the positive attitudes subscale after three months, while still improved over scores at baseline, were significantly reduced compared to the immediate post-intervention score, suggesting some attenuation of the initial intervention effect (40.3 vs. 44.8, a 4.5 point reduction [95% CI -7.9, -1.0]).

Fig. 1. Health Care Provider Attitude Scores Over Time.

* All scores significantly different from baseline in comparison at P ≤ 0.05.

We conducted bivariate secondary analyses examining the association of clinician characteristics with their attitudes towards SCD patients at baseline, and we conducted multivariable analyses to identify associations between clinician characteristics and attitudes independent of the intervention effects and potentially confounding clinician characteristics. At baseline, female respondents exhibited more negative attitudes than males (43.6 vs. 33.5, P = 0.012), and nurses exhibited more negative attitudes than residents (45.8 vs. 33.9, P = 0.041). No clinician characteristics were significantly associated with positive or red-flag behavior attitudes at baseline.

In multivariable analyses, nurses exhibited less positive attitudes than physicians (ßnurse = -9.9, P = 0.043). Nurses and midlevel providers exhibited greater endorsement of red-flag behavior attitudes than did physicians (ßnurse = 13.8, P <0.001; ßmidlevel = 12.1, P = 0.011). Respondents in the 60-69 age group exhibited greater endorsement of red-flag behavior attitudes than those in the 20-29 age group (ß60-69 = 20.7, P = 0.016).

Conclusions/Lessons Learned

Our study provides evidence that a brief video-based intervention can be successful in improving ED provider attitudes towards SCD patients and appears to be sustainable for at least three months. Evidence shows that health care provider attitudes can impact both perceived and actual health care delivery (5,7). Negative provider attitudes towards SCD patients are a known barrier to the delivery of high quality pain management to this patient population (5,7). We recently reported the results of a study finding that patients who perceived that clinicians discriminated against them because of their SCD status, reported a greater burden of SCD pain than did those with no perception of disease-based discrimination (10). This further suggests that interventions to improve provider attitudes towards SCD patients may improve SCD patients’ experience of pain, in addition to optimal management of their pain.

The video used in the current study was unique in that it 1) focused specifically on the challenges in caring for patients with SCD experienced by emergency medicine providers and 2) was brief and easily accessible as a short online video.

Our study not only improved the perceptions of providers at our institution, but also demonstrated that attitudinal changes elicited by the brief video-based intervention are sustainable for a period of time beyond the immediate post-intervention period with only a minimal attenuation of effects. Nevertheless, the fact that we observed some attenuation in the effect of the video on positive attitudes towards the SCD population suggests that there is a need to provide continuing education. Additional research is needed to determine the best schedule and methods to provide continuing education to ensure persistence of attitudinal change elicited by the intervention.

We found that nurses exhibited a lower level of positive feelings of affiliation towards SCD patients than did physicians. Further, we found that when compared to physicians, nurses and midlevel providers exhibited a higher level of belief that certain behaviors often demonstrated by SCD patients are “red-flags” that the patient is inappropriately drug seeking. Nurses and midlevel providers are often at the forefront in delivering patient care, and typically spend more time with patients than physicians. Because of this, it is possible that nurses and midlevel providers have a greater intensity of exposure to the high-utilizing subset of patients, thus causing them to be more likely to view certain behaviors as red-flags. Our findings underscore the need for educational modules targeted to these clinical providers in particular in order to encompass aspects of their relationships with SCD patients that may be more unique to their clinical roles. It also serves as a reminder for attending physicians to model their entire inter-professional teams’ compassionate and unbiased care for this patient population.

We found that the oldest ED providers were more likely than the younger providers to endorse the concept of red-flag behaviors. This might reflect generational differences in the education that these groups of providers received about SCD patients. It also may reflect older providers having a great level of exposure to the “high-utilizing” subset of SCD patients over their careers, which may have affected their attitudes in the same way as nurses and midlevel providers.

We do acknowledge certain limitations of our study. First, this intervention was administered at one academic institution in a large urban academic setting, and the patients and providers featured in the video intervention were from the same institution. Therefore, the extent to which our video will demonstrate the same level of impact among different providers at other institutions is not known. Second, our results may be subject to a selection bias as the providers who agreed to participate in the study may have been more open to changing their attitudes and practices towards SCD patients compared to providers who chose not to participate. It is possible that our results are subject to a social desirability bias that is often inherent to the pre- and posttest design. However, the fact that the attitudinal improvements we observed immediately post-intervention were persistent three months following the intervention is suggestive of some level of real change induced by the intervention. Although we showed that the video intervention changed ED provider attitudes, it remains to be seen whether this translated to changes in clinical practice and improvements in patient satisfaction with the care they received over the study period. We did not have a separate control group for comparison and the participants acted as their own controls. This allowed us to meet our sample size to impart sufficient power to our study given a finite number of providers at the institution’s ED. Our study results are also limited by a social desirability bias; however, we do plan to undertake a subsequent study to assess the true impact on patient satisfaction and on change in practice if any.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our research supports the utility of brief video-based educational interventions as viable methods of improving the attitudes of ED providers towards SCD patients exhibiting pain. This may be an important first step along the path towards improved management of sickle cell pain crises by mitigation, if not total elimination of biases that interfere with optimal pain control in this vulnerable population. From the clinician perspective, increased awareness of the SCD pain experience and the challenges often faced by persons with SCD seeking care for their pain may lead to better communication with these patients regarding their pain management. Given the brief convenient online nature of this video, we believe that our intervention can be easily integrated into formal ED provider training efforts, especially in EDs with high SCD patient volumes. Further studies are needed to assess the long-term impact of such intervention on clinical practice (i.e., delivery of optimal and timely pain management) as well as any effects it may have on patient experiences and satisfaction. Nevertheless, we believe that this intervention can contribute to larger and much needed efforts designed to ensure that all persons with SCD receive the same level of high quality, unbiased pain management that all patients are due.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Dugas reports a grant from the Blaustein Pain Foundation, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Haywood’s effort on the project was supported by a career development award from the NHLBI (#1K01HL108832-01).

Appendix I

General Perceptions About Sickle Cell Patients Scale (Haywood et al., 31-Item Long Version)

Your completion of this survey or questionnaire will serve as your consent to be in this research study.

| SECTION A | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What percentage of patients with Sickle Cell Disease: | >5% | 6-20% | 21-50% | 51-75% | >75% | |

| 1 | Over-report (exaggerate) pain? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | Fail to comply with medical advice? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | Abuse drugs, including alcohol? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | Manipulate you or other providers? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | Are drug-seeking when they come to the hospital? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | Are frustrating to take care of? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | Makes me feel glad that I went into medicine? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | Are the kind of person I could see myself friends with? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | Are satisfying to take care of? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | Are easy to empathize with? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| SECTION B | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Please indicate your opinion about the degree to which each of the following is a sign that a patient with sickle cell disease is inappropriately/unnecessarily drug-seeking: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Not sure but probably Disagree | Not sure but probably Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | Patient requests specific narcotic drug and dose | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | Patient changes his/her behavior (e.g. appears in greater distress) when provider walks in room | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3 | Patient appears comfortable (e.g. talking on phone or watching TV) while complaining of severe pain | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4 | Patient has history of disputes with staff | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5 | Patient rings bell for nurse and constantly asks for more pain medication before next dose is due | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6 | Patient has history of signing out against medical advice | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7 | Patient tampers with a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) device | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8 | Patient complains of severe pain but has no change in hemoglobin, a normal reticulocyte count, and a normal physical exam. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| SECTION C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Not sure but probably Disagree | Not sure but Probably Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | The most reliable indicator of the existence and intensity of acute pain episodes in sickle cell disease is patient self-report. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | An important focus of the health care provider in treating acute pain episodes in sickle cell disease is adequate pain relief. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3 | An important focus of the health care provider in treating acute pain episodes in sickle cell disease is prevention of drug addiction. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4 | A patient with sickle cell disease can present with crisis in the absence of any objective measures (e.g baseline hemoglobin, normal reticulocyte count, normal physical exam). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| SECTION D | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Please state how often the following things occur: | Always | Most of the time | Some of the time | Rarely | Never | |

| 1 | I am bothered by the way some doctors treat patients with sickle cell disease. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | I am bothered by the way some nurses treat patients with sickle cell disease. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | I am bothered by the way some of my own friends and colleagues treat patients with sickle cell disease. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | I try to imagine myself in the shoes of a patient with sickle cell disease when providing care for them. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| SECTION E | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In your opinion, many patients with sickle cell disease who exaggerate pain do so as a result of: | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Not sure but probably Disagree | Not sure but probably Agree | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 1 | Inappropriate or unnecessary drug addiction/ drug seeking | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 | Inadequate pain management by doctors and nurses | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3 | Personality disorders | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4 | Previous poor pain management in the healthcare system | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5 | A perception among patients of the need to ‘act out’ in order to get appropriate pain medication | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Thank you for taking the time to participate.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood C., Jr The burden of emergency department use for sickle-cell disease: an analysis of the national emergency department sample database. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:797–799. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decosterd I, Hugli O, Tamches E, et al. Oligoanalgesia in the emergency department: short-term beneficial effects of an education program on acute pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geller AK, O’Connor MK. The sickle cell crisis: a dilemma in pain relief. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:320–323. doi: 10.4065/83.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro BS, Benjamin LJ, Payne R, Heidrich G. Sickle cell-related pain: perceptions of medical practitioners. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14(3):168–174. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(97)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glassberg JA, Tanabe P, Chow A, et al. Emergency provider analgesic practices and attitudes toward patients with sickle cell disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamison C, Brown HN. A special treatment program for patients with sickle cell crisis. Nurs Econ. 2002;20:126–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haywood C, Jr, Beach MC, Lanzkron S, et al. A systematic review of barriers and interventions to improve appropriate use of therapies for sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:1022–1033. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanabe P, Stevenson A, Decastro L, et al. Evaluation of a train-the-trainer workshop on sickle cell disease for ED providers. J Emerg Nurs. 2013;39:539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haywood C, Jr, Lanzkron S, Hughes MT, et al. A video-intervention to improve clinician attitudes toward patients with sickle cell disease: the results of a randomized experiment. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:518–523. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1605-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haywood C, Jr, Diener-West M, Strouse J, et al. IMPORT Investigators. Perceived discrimination in health care is associated with a greater burden of pain in sickle cell disease. J Pain Symptom Management. 2014;48:934–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]