Abstract

Recycling of neurotransmitters is essential for sustained neuronal signaling, yet recycling pathways for various transmitters, including histamine, remain poorly understood. In the first visual ganglion (lamina) of Drosophila, photoreceptor-released histamine is taken up into perisynaptic glia, converted to carcinine, and delivered back to the photoreceptor for histamine regeneration. Here, identify an organic cation transporter, CarT (carcinine transporter), that transports carcinine into photoreceptors during histamine recycling. CarT mediated in vitro uptake of carcinine. Deletion of the CarT gene caused an accumulation of carcinine in laminar glia accompanied by a reduction in histamine, resulting in abolished photoreceptor signal transmission and blindness in behavioral assays. These defects were rescued by expression of CarT cDNA in photoreceptors, and were reproduced by photoreceptor-specific CarT knockdown. Our findings suggest a common role for the conserved family of CarT-like transporters in maintaining histamine homeostasis in both mammalian and fly brains.

Keywords: Vision, Neurotransmitter recycling, Histamine, Membrane transporter

INTRODUCTION

Neurons communicate at synapses by releasing neurotransmitters. To maintain stable levels of transmitters for sustained signal transmission, neurons need to recycle various neurotransmitters (Bröer and Brookes, 2001; Edwards and Meinertzhagen, 2010) either directly or indirectly. In direct mechanisms, upon release, neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, dopamine and glycine are immediately taken back into the presynaptic neuron by specific transporters in the axon membrane (Freeman and Doherty, 2006). In indirect pathways, transmitters including glutamate and histamine are cleared from the perisynaptic space by astrocytes and other types of glial cells (Borycz et al., 2012; Bringmann et al., 2013; Freeman and Doherty, 2006) and then inactivated before being delivered back to the neuron for regeneration (Bringmann et al., 2013). Currently, metabolic enzymes in the recycling process of glutamate, GABA, and histamine have been identified (Borycz et al., 2002; Bringmann et al., 2013; Roth and Draguhn, 2012). In addition, a variety of membrane transporters for glutamate, GABA and their recycling metabolites have also been found in glial and neuronal membranes (Blakely and Edwards, 2012; Elsworth and Roth, 1997; Gadea and López-Colomé, 2001; Roth and Draguhn, 2012). Although there have been studies (Huszti et al., 1998; Yoshikawa et al., 2013) on how histamine, a neurotransmitter crucial for the maintenance of wakefulness, the sleep-wake cycle and the regulation of cognitive functions (Panula and Nuutinen, 2013), is cleared from the neuronal environment, the mechanism underlying the recycling of histamine remains unknown.

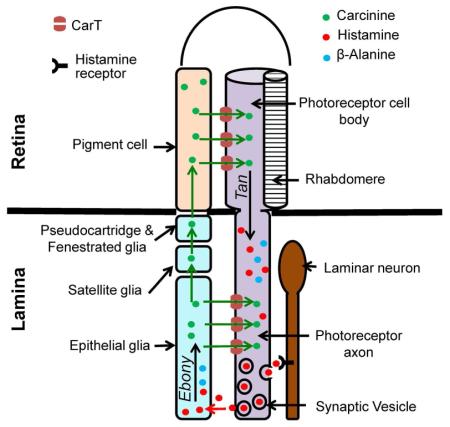

The Drosophila visual system has been used as a model for the investigation of histamine recycling. All peripheral photoreceptors in each ommatidium, the unit of the Drosophila compound eye (Montell, 2012), project axons to the first layer of the visual neuropil, the lamina (Edwards and Meinertzhagen, 2010). Upon light stimulation, photoreceptor axons release histamine to hyperpolarize laminar projecting neurons, i.e., large monopolar cells (LMCs) (Sarthy, 1991). All neuronal processes in the lamina, including photoreceptor axon terminals, are wrapped laterally by epithelial glial cells (Meinertzhagen and O’Neil, 1991). Although the proximal edge of the lamina is sealed with marginal glia, the distal edge of the laminar neuropil is separated from the retina by four glia layers: two surface glia underneath the retina, and distal and proximal satellite glia that wrap around cell bodies and initial axon segments of LMCs, respectively (Edwards and Meinertzhagen, 2010). Photoreceptor-released histamine is removed from the extracellular space, mostly by epithelial glia (Edwards and Meinertzhagen, 2010). In these glia, an N-β-alanyl-biogenic amine synthetase termed Ebony conjugates histamine to β-alanine to form the inactive metabolite carcinine for storage and transport (Richardt et al., 2002; Ziegler et al., 2013). Carcinine can be released into the laminar neuropil region and directly transported back into photoreceptor axons. Alternatively, it can also be transported to the retina via the gap-junctional glial network (Saint Marie and Carlson, 1985) and delivered into the cell bodies of photoreceptors (Chaturvedi et al., 2014). In the photoreceptor, carcinine is cleaved by the peptidase Tan to regenerate histamine and β-alanine (Borycz et al., 2002; Gavin et al., 2007). Because the recycling of histamine is more energy efficient compared to de novo synthesis through photoreceptor histidine decarboxylase (HDC), it is considered a dominant pathway in the maintenance of an adequate histamine level (Borycz et al., 2000; Burg et al., 1993).

Although both metabolic enzymes in the recycling of histamine have been identified in the fly visual system, the transporters that carry histamine, carcinine and β-alanine across the membranes of glia and photoreceptor neurons remain unknown. Here, we identified an organic cation transporter (OCT), named carcinine transporter CarT, that functions in the photoreceptor.

RESULTS

CarT is essential for synaptic transmission between the photoreceptor and laminar neurons

In the fly electroretinogram (ERG), transient spikes at the onset and offset of a light flash correspond to the postsynaptic potentials of laminar neurons, whereas a sustained potential during light stimulation results mainly from the depolarization of photoreceptor cells in the retina (Alawi and Pak, 1971; Belusic, 2011; Hardie and Raghu, 2001; Heisenberg, 1971). In an RNAi-based screen for vision-related genes, we found that when the gene CG9317, i.e., CarT, was knocked down ubiquitously using a tubulin-Gal4 driver, both ON and OFF transients of the ERG were missing (Figures 1A, 1B and 1C), suggesting that synaptic transmission from photoreceptors to laminar neurons was impaired. This visual function of CarT is coherent with the expression data in Fly-atlas, which shows 17-fold enrichment of CG9317 in the eye.

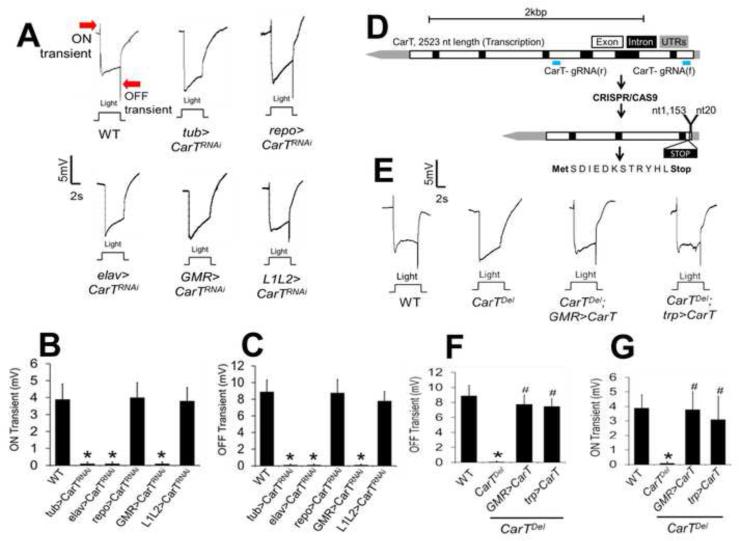

Figure 1. Identification of CarT as a photoreceptor transporter indispensible for the signal transmission to laminar neurons.

(A) Electroretinogram (ERG) recordings of Canton-S (WT, for wild type) and CarT knockdown (KD) flies indicating loss of photoreceptor synaptic transmission in pan-neuron KD and retinal cell-specific KD flies. As the only neuron in the retina, photoreceptor is highly likely the cell type where CarT functions. The Gal4 lines tub (tubulin-Gal4 + dicer), elav, repo, GMR and L1L2 drove RNAi respectively in all cell types, neurons, glia, retinal cell and L1 and L2 cells (two major laminar neurons postsynaptic to photoreceptors). Red arrows indicate ON and OFF transients, which are electric activities derived from the primary visual transmission. See also Figure S1

(B and C) Quantitation of the ON and OFF transient amplitude, respectively, shows that the transients are absent when CarT is KD in all cell types, all neurons, or retinal cells, but are similar to WT when CarT is KD in glia cells or L1 and L2 laminar neurons. The data is presented as mean ± SD. The symbol * indicates p < 0.05 when compared with WT in two-tailed test. Ten flies were measured for each genotype, i.e., n=10.

(D) CRISPR-Cas9 based gene knockout with two guide RNAs deleted 1,132 nucleotides from the CarT gene, starting from the nt21 (with the first nucleotide of the start codon as nt1) in exon 1 to nt1152 in exon 4, and shifted the coding frame. As a consequence, the translation is stopped after the synthesis of a 13 amino acid small peptide. Thus, the CarTDel mutant does not express any functional CarT protein.

(E) The CarTDel mutant lacks both ON and OFF transients, which were rescued by expression of a WT CarT cDNA through either the GMR- or trp-Gal4 driver, indicating that the CarT function in photoreceptor is essential for photoreceptor-laminar neuron signal transmission.

(F and G) Quantitation of the ON and OFF transient amplitude, respectively, confirms the rescue of the CarTDel mutant phenotype by specific expression of CarT in retinal cells (GMR) or in the photoreceptor (trp). The symbols * and # indicate p < 0.05 when compared with WT and the CarTDel mutant, respectively, in two-tailed test (n=10).

To determine the functional site for CarT, we generated tissue-specific knockdowns in glia and neurons using pan-glia (repo, for reversed polarity) and pan-neuronal (elav, for embryonic lethal abnormal vision) Gal4 drivers, respectively (Figures 1A, 1B and 1C). Interestingly, neuronal knockdown of CarT removed both ON and OFF transients from the ERG, whereas glial knockdown had no significant effect (Figures 1A, 1B and 1C), suggesting that CarT is present in neurons. To identify the specific neuronal type that expresses CarT, we knocked down CarT in photoreceptors and lamina neurons using GMR-Gal4 and L1L2-Gal4 drivers, respectively (Figure 1A). Notably, CarT knockdown in photoreceptors reproduced the ERG phenotype with loss of ON and OFF transients, whereas knockdown of CarT in laminar neurons did not result in any abnormal ERG (Figures 1A, 1B and 1C). However, morphology of the retina and lamina remained intact in CarT knockdown flies (Figure S1A and S1B). These results suggest that CarT functions in photoreceptors and is essential for synaptic transmission to downstream laminar neurons.

To confirm that loss of CarT in photoreceptors impairs visual transmission, we generated a CarT mutant with the gene deleted in the whole animal using the CRISPR/CAS9 approach (Bassett and Liu, 2014; Gratz et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2014) (Figure 1D). Cutting at both sites of two guide RNAs (gRNAs) in a conserved domain sequence of CarT resulted in a deletion allele, which we further confirmed by sequencing. The deletion of 1,132 nucleotides resulted in a frame shift with the introduction of a stop codon and translated a small peptide with a 13 amino acid sequence (MetSDIEDKSTRYHLStop) instead of the CarT protein. Flies with this deletion allele CarTDel, showed a non-transient ERG phenotype similar to CarT knockdown in flies (Figures 1E, 1F and 1G). Furthermore, expression of a WT CarT cDNA specifically in photoreceptors using GMR or trp (transient receptor potential)-Gal4 rescued the ERG phenotype of the CarTDel fly (Figures 1E, 1F and 1G). Thus, the expression of CarT in photoreceptors is both sufficient and essential for synaptic transmission from the photoreceptor to laminar neurons.

In control experiments, each Gal4 driver lines alone did not cause any ERG abnormality in the absence of the UAS-CarT and UAS-CarTRNAi transgenes (Figure S1C). Conversely, the UAS-CarT and UAS-CarTRNAi transgenes alone had no effect on the fly ERG either (Figure S1C).

Deletion of CarT causes accumulation of carcinine outside of photoreceptors

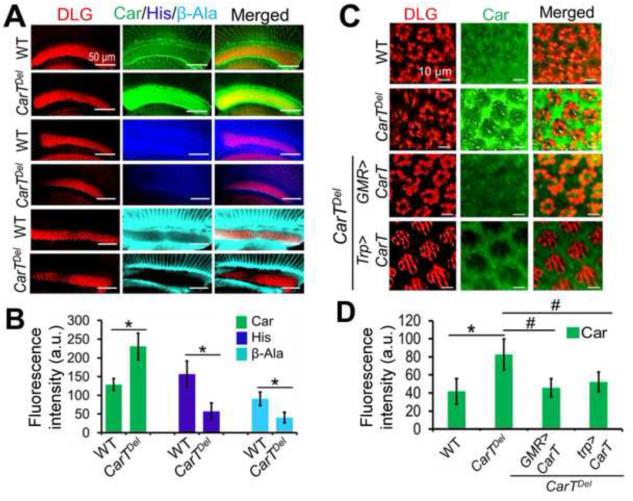

Bioinformatic analyses indicated that CarT has strong homology with human OCTs in the SLC22 transporter family (Farthing and Sweet, 2014; Koepsell, 2013) at both primary and secondary structural levels as indicated by blast results. CarT showed 23-32% identity with human SLC22A family members and also showed similarity in their conserved motifs i.e. MFS-1 (Major Facilitator Superfamily) and Sugar transporter motifs (Figures S2 and S3). We therefore hypothesized that CarT may be a membrane transporter involved in histamine recycling, which is essential for fly visual signal transmission. If so, CarT could either uptake carcinine from outside into photoreceptors or transport β-alanine from photoreceptors to the glia. If CarT transports carcinine from surrounding glia into photoreceptors, the loss of CarT would alter the carcinine distribution pattern. Additionally, because carcinine is metabolized into histamine and β-alanine within the photoreceptors by the enzyme Tan, blocking the transport of carcinine into photoreceptors should result in accumulation of carcinine in the extracellular space or surrounding glia and a reduction of its metabolites, i.e., histamine and β-alanine. By contrast, if CarT functions as a β-alanine transporter, β-alanine should accumulate in the photoreceptors of CarTDel flies and the overall carcinine level should be reduced. To differentiate between these two possibilities, we immunostained carcinine and its metabolites in the visual system of CarTDel flies (Figures 2A-D) and in rescued flies with expression of CarT in photoreceptors (Figures 2C and 2D). We observed the accumulation of carcinine in the lamina of CarTDel flies (Figures 2A-2D), but no β-alanine accumulation was detected in the photoreceptors (Figures 2A and 2B). However, the overall levels of β-alanine and histamine were actually reduced in CarTDel flies (Figures 2A and 2B). Therefore, our study suggests that CarT functions as a carcinine transporter in photoreceptors.

Figure 2. Loss of CarT in photoreceptors causes accumulation of carcinine in lamina.

(A) Co-labeling of discs large (DLG, a marker for photoreceptor terminals in the lamina (Hamanaka and Meinertzhagen, 2010), red) and carcinine (green), histamine (dark blue) and β-alanine (light blue) in the lamina of WT and CarTDel flies. The immunostaining data shows that carcinine was accumulated in the lamina of the CarTDel fly. Conversely, the levels of histamine and β-alanine were reduced compared to WT.

(B) Quantitation of the immunofluorescence intensity shows changed levels of carcinine (Car), histamine (His) and β-alanine (β-Ala) in the CarTDel mutant. The fluorescent staining intensity of a selected region was measured using the ImageJ software, and was subtracted with that of a background region of the same size. The mean value of 3 successive optic slices was obtained for each image. After further averaging among 8 flies, the mean intensity (in arbitrary unit, a.u.) and SD are shown for each genotype and antigen. The symbol * indicates p < 0.05 when compared with WT in two-tailed test.

(C) Co-labeling of DLG and carcinine in cross-lamina sections of WT, CarTDel and rescue flies. A large amount of carcinine was accumulated in the space of epithelial glia in the lamina of CarTDel flies, which was prevented in rescue flies by expression of the CarT cDNA in photoreceptors through the GMR- and trp-Gal4 driver.

(D) Quantitation of the relative staining intensity for carcinine in WT, CarTDel and rescued flies. The symbols * and # indicate p < 0.05 when compared with WT and the CarTDel mutant, respectively, in two-tailed test (n=8).

CarT is a carcinine transporter and uptakes carcinine into S2 cells

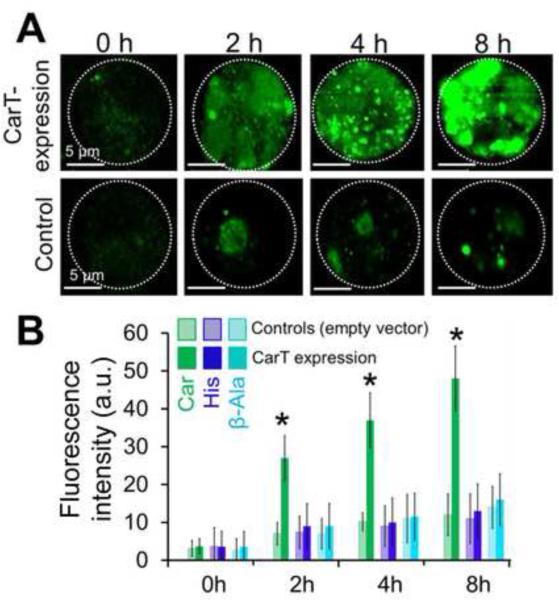

To confirm that CarT transports carcinine, we overexpressed V5- and His-tagged CarT in S2 cells (Figures 3A and 3B). After confirming the expression of CarT by antibody staining against the V5 tag peptide (Figure S4B), we separately incubated the cells with carcinine, β-alanine and histamine (Figure 3) and then checked the levels of carcinine, β-alanine and histamine within the cell over a time period of 0-8 h by immunostaining (Figure 3B). The carcinine level in CarT-overexpression S2 cells was significantly higher than in control cells (Figures 3A and 3B). The immunostaining intensity of carcinine was 47% after 8 h of carcinine treatment in cells expressing CarT, whereas it was only 12% in the control cells (Figure 3). By contrast, the immunostaining intensities of β-alanine and histamine in CarT-expressing cells were comparable to those of the controls after 8 h of incubation (Figure 3B). These in vitro results suggest that CarT is a carcinine transporter.

Figure 3. CarT transports carcinine in transfected S2 cells.

(A) Staining with the carcinine antibody shows the time course of carcinine uptake into S2 cells transfected with either a pAc5.1-CarT-V5-His DNA construct or the empty vector (as control). The cells were fixed for staining 0-8 hours (0 h, 2 h, 4 h and 8 h) after the carcinine incubation. Carcinine was gradually accumulated in the CarT-expressing cells. Each image shows a single S2 cell with the cell boundary marked by the dash-line circle. The construct/vector transfection in all examined cells was confirmed by staining with antibodies against the V5 tag peptide (See Figure S4).

(B) Quantitation of immunofluorescence intensities for carcinine, histamine and β-alanine in CarT-expressing and control S2 cells, over the time period of 8-hour incubation with the respective molecules. The results indicate that the expression of CarT significantly increased the uptake of carcinine (p (*) < 0.05, compared with the control, two tailed test, n=25 cells), but not that of histamine and β-alanine.

Deletion of CarT impairs fly vision

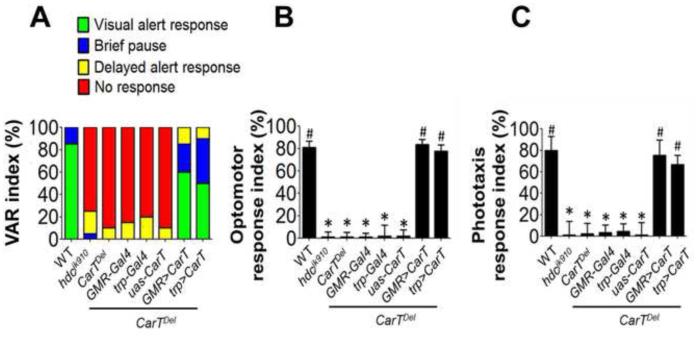

Because we hypothesize that CarT is important for histamine recycling in the fly visual system, the loss of CarT should disrupt the histamine recycling leading to impaired fly vision at a behavior level due to abnormal histaminergic synaptic signaling. We employed three different visual behavior assays to test whether the vision of CarTDel flies was impaired (Figures 4A-4C). In the visual alert assay (Figure 4A), which measures the visual alertness in the fly toward a moving object, we found that 90% of CarTDel flies were non-responsive and that 10% of flies showed delayed alert responses. This visual defect of CarTDel was at least as severe as that in a blind mutant hdcjk910 (Figure 4A), which lacks the enzyme HDC. Expression of CarT in photoreceptors using GMR-Gal4 recovered WT visual alert responses in 60% of flies, 25% of rescued flies showed brief pause, and only 15% flies showed delayed alert responses. Expression of CarT through another photoreceptor-specific driver, trp-Gal4, also rescued the defect of CarTDel, with 50% of flies showing WT visual alertness, 40% showing a brief pause and 10% having delayed alert responses. These results indicate that CarT in photoreceptors is essential for visual alertness in flies.

Figure 4. Loss of CarT in photoreceptors causes blindness in behavior assays.

(A) Deletion of CarT caused the fly irresponsive to a moving block in the visual alert response (VAR) assay, a defect also observed in a blind mutant hdcjk910. Expression of the CarT cDNA in photoreceptors through the GMR- and trp-Gal4 driver rescued the VAR defect of CarTDel. Flies with normal VAR froze immediately upon the moving of the block and stayed still for at least 10 seconds, while those with brief pause or with delayed response stopped moving for only 1-3 seconds either instantly or after walking very close to the moving path of the block, respectively. Twenty flies were assayed for each genotype.

(B) In the optomotor response assay, the fly migrating response to moving black strips was severely impaired in CarTDel flies. This defect was rescued by expression of CarT in photoreceptors. Three sets of 50 flies were examined for each genotype, and each set was tested four times to obtain an average index value. The symbols * and # indicate p < 0.001 when compared with WT and the CarTDel mutant, respectively, in two-tailed test.

(C) CarTDel flies lost their phototaxis behavior, which was recovered after expressing CarT in photoreceptors. Six sets of 10 flies were examined for each genotype. The symbols * and # indicate p < 0.001 when compared with WT and the CarTDel mutant, respectively, in two-tailed test.

In an optomotor response assay (Figure 4B) that measures fly visual behavior in terms of motion detection, WT flies have an inherent tendency to move in the opposite direction of the moving black and white strips. However, if the fly is blind or visually impaired, it won’t respond to the moving strips and will keep moving randomly. In this experiment, only 1% of CarTDel flies showed a positive optomotor response in contrast to 81% of WT flies that showed a very strong optomotor response. This visual defect was rescued by the expression of CarT in photoreceptors using GMR and trp-Gal4 drivers (Figure 4B). Thus, CarT-mediated carcinine uptake into photoreceptors is important for the perception of motion in flies.

The phototaxis assay (Figure 4C) measures the light detection ability of flies and uses their inherent tendency to move toward light. The WT flies (80%) showed a strong positive response toward light. However, most of the CarTDel flies could not respond to light and only 2% of flies could respond to light. Expression of CarT in photoreceptors using GMR and trp-Gal4 significantly improved the phototaxis response of the CarTDel flies.

Therefore, loss of CarT in the photoreceptors of flies causes virtual blindness in all three visual behavioral assays, highlighting the importance of CarT-mediated carcinine uptake in photoreceptors and the entire histamine recycling pathway in fly vision.

DISCUSSION

During light stimulation, fly photoreceptors constantly release histamine to hyperpolarize LMC neurons in the lamina neuropil. It is estimated that vesicular histamine in photoreceptor termini would be depleted within approximately ten seconds in the absence of additional histamine supply (Borycz et al., 2005). The continuation of visual transmission depends on the recycling of histamine, in which the visual glia play a pivotal role. The released histamine is taken up by epithelial glia (Edwards and Meinertzhagen, 2010), converted into carcinine through Ebony (Richardt et al., 2002; Ziegler et al., 2013), and delivered back to photoreceptors either directly or indirectly through the laminar glia network (Chaturvedi et al., 2014; Romero-Calderón et al., 2008). In the photoreceptor, carcinine is cleaved by Tan to regenerate histamine (Borycz et al., 2002; Gavin et al., 2007). Although the metabolizing enzymes in both the glia and photoreceptors have been identified, transporter proteins that carry histamine and carcinine across the membranes of glia and photoreceptors have previously been unknown.

A transporter encoded by the gene inebriated (ine) was proposed to mediate clearance of carcinine from the extracellular space of the lamina (Gavin et al., 2007). However, the carcinine-transporter activity of the Ine protein has never been demonstrated in vitro (Chiu et al., 2000). In ine mutants, we could not detect any significant changes in either the distribution pattern or the level of carcinine (Chaturvedi, Luan and Li, unpublished observations). The mutant flies behaved similarly to WT flies according to the visual alert and optomotor assays, indicating normal visual transmission. Thus, Ine may function in a process irrelevant to histamine recycling.

Our data show that that CarT mediates the uptake of carcinine in photoreceptors, revealing the identity of the membrane transporter involved in the recycling of histamine in the visual system. The carcinine-transporter activity of CarT was demonstrated in transfected S2 cells, and supported by the accumulation of carcinine in the laminar glia of CarTDel flies. In additional, the CarTDel flies have almost the same visual defects as ebony and tan mutants (Borycz et al., 2002), including a reduced level of visual histamine, disrupted visual transmission according to the ERG phenotype and impaired vision as revealed in behavioral assays, which suggests that CarT and the enzymes Ebony and Tan function in the same pathway of histamine recycling. This visual function of CarT is further confirmed by findings from two other laboratories (Stenesen et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015) published during the revision of our work.

Given that knockdown of CarT in the glia does not affect visual transmission and that the expression of CarT in photoreceptors alone is sufficient to rescue the CarTDel phenotype, CarT may not mediate the release of carcinine from visual glia. It is likely that laminar glia express a different membrane transporter to release carcinine. ABC transporters encoded by the genes white, brown and scarlet in pigment cells appear to modulate the level of visual histamine through unknown mechanisms (Edwards and Meinertzhagen, 2010; Mackenzie et al., 2000). Whether any of these transporters participates in carcinine/histamine trafficking in laminar glia remains to be investigated. Alternatively, carcinine could be released from laminar glia through vesicular exocytosis. A vesicular monoamine transporter VMAT-B in subretinal fenestrated glia, the distal surface glia of the lamina, is required to maintain the overall level of visual histamine (Romero-Calderón et al., 2008). Although the proposed substrate of VMAT-B is histamine, this transporter could also pack carcinine into intracellular vesicles for exocytosis due to the structural similarity of histamine and carcinine.

Further study of the subcellular localization of CarT in fly photoreceptors will help reveal the exact pathway of histamine/carcinine trafficking. For instance, whether carcinine is sent to the cell body/soma or the axon of photoreceptors for re-uptake, and whether the re-uptake involves capitate projection, a special membrane invagination of epithelial glia formed within photoreceptor axons (Meinertzhagen and O’Neil, 1991; Stark and Carlson, 1986), remains unknown.

The identification of carcinine transporters in Drosophila is potentially of great significance to the study of histamine homeostasis in mammalian brains. As an important neurotransmitter, histamine regulates diverse brain functions through G protein-coupled receptors, such as promoting attentive wakefulness and regulating cognitive functions and food intake (Panula and Nuutinen, 2013; Passani et al., 2000; Thakkar, 2011). Various sleep disorders, cognitive dysfunction, motor disorders and schizophrenia are associated with abnormal histamine signaling (Ito, 2000; Nuutinen and Panula, 2010; Panula and Nuutinen, 2013). How the brain maintains histamine homeostasis for normal function, however, remains to be investigated. It has been reported that glial cells including astrocytes clear histamine from the neuronal environment, probably through OCT3 or plasma membrane monoamine transporter (PMAT), and inactivate it through histamine-N-methyltransferase (Huszti et al., 1998; Yoshikawa et al., 2013). This inactivation mechanism leads to the degradation of histamine and is not beneficial to the maintenance of histamine levels. Interestingly, high levels of carcinine have been detected in most histamine-abundant tissues of humans and rodents, including the brain (Chen et al., 2004; Flancbaum et al., 1990). The concomitance of these two molecules suggests the existence of carcinine-mediated recycling of histamine in mammals. Confirmation of the glia-mediated histamine/carcinine recycling in the brain requires the identification of carcinine transporters in the membrane of neurons. Because CarT belongs to the OCT family, OCTs will be top candidates in the search for neuronal carcinine transporters in mammals.

Carcinine transporters may also regulate physiological functions in mammalian peripheral tissues. The co-existence of carcinine and histamine has been observed in the heart, kidney, stomach and intestines (Flancbaum et al., 1990). In combination with histamine-carcinine converting enzymes, carcinine transporters may control the distribution and level of histamine, and ultimately regulate histamine-mediated peripheral functions, such as vasodilation (Greaves and Sabroe, 1996), inflammation (Jutel et al., 2009) and gastric acid release (Schubert and Peura, 2014; Schubert, 2010). In addition, because carcinine is a natural antioxidant with hydroxyl-radical-scavenging activity (Babizhayev et al., 1994; Babizhayev and Yegorov, 2010; Marchette et al., 2012), carcinine transporters may distribute carcinine for the protection of cells against oxidative stress. Thus, the identification and location of carcinine transporters will aid the understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of both histamine and carcinine-mediated physiological functions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Please see Supplemental Materials for the sources of fly lines and methods of CarT gene deletion, ERG recording, immunostaining and the S2 carcinine uptake assay. All the strains with white eyes were crossed into a Canton-S background with red eyes before functional tests.

Visual alert assay (VAR assay)

The VAR assay was performed as described (Chaturvedi et al., 2014). An overnight starved fly was placed into a vertical white chamber (5.5 × 2 × 0.5 cm) covered with a thin glass slide from one side. The fly was then allowed to acclimatize for 30 min inside the chamber and then a drop of molasses was placed on the upper side of the chamber to induce the starved fly to climb up. As the fly reached the middle of the chamber it was challenged with a manually controlled moving block (a black colored 0.4 cm cube) from left to right, across the visual field of the fly. The response of the fly was recorded with a video camera connected to a computer. The result for each genotype (n= 20) is the mean of the percentages of flies showing various responses (freezing, brief pause, delayed response, and no response).

Optomotor assay

The walking optomotor responses in flies were assayed as described (Rendahl et al., 1992; Zhu et al., 2009) with modifications. Groups of 50 flies were enclosed onto the surface of a 7” LED monitor using a clear, rectangle plastic cover of 0.5” height. When computer-generated black vertical strips moved in a bright background (~220 lux) from one side to the other, most flies with normal vision migrated in the opposite direction. During the test, flies were keeping startled by gentle shaking of the chamber to evoke optimal locomotor performance. The response index is calculated as (n1−n2)/(n1+n2), where n1 is the number of flies moving to the right side, and n2 is to the wrong side.

Phototaxis assay

Phototaxis assays were carried out in a dark room following the counter current procedure as described (Benzer, 1967; Luan et al., 2014), with modifications. Groups of 10 flies were placed in a long transparent tube (20 cm), and after 5 min of dark adaptation, the tube was gently patted to place the flies at one end. The opposite end of the tube was then attached to a white light source, and flies that moved across the middle line within 30 seconds were counted as responsive. The test was also performed in the dark, and the performance index for phototaxis was calculated by subtracting the number of “responsive” flies in dark from the light responsive flies and divided by the total number of flies (10) in the tube.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Values are represented as the mean ± SD, and statistical tests of the significance of difference between values were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-test, where p<0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CarT mediates the uptake of carcinine in transfected S2 cells.

CarT is required for carcinine trafficking and maintenance of eye histamine levels.

The expression of CarT in photoreceptors is essential for fly visual transmission.

Loss of CarT in the fly photoreceptor causes blindness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank VDRC, TRiP and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for fly stocks and antibodies. We thank Dr. Michael H. Brodsky for his help in CRISPR/CAS9 deletion, Dr. M. Freeman for sharing flies and reagents, Dr. J. Bai and Ms. C.M. Quigley for comments on the manuscript. This work is supported by NIH grant R01EY021796 to H-S. L.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

Supplemental information includes 4 supplemental figures and additional methods.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.C. and H-S.L. conceived the project, analyzed results, and wrote the manuscript. R.C. performed most of experiments including cloning, deletion, ERG, cell biological, and biochemical experiments. R.C. and Z.L. performed Optomotor assay while P.G generated trp-Gal4 driver line.

REFERENCES

- Alawi AA, Pak WL. On-transient of insect electroretinogram: its cellular origin. Science. 1971;172:1055–7. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3987.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babizhayev M. a, Seguin MC, Gueyne J, Evstigneeva RP, Ageyeva E. a, Zheltukhina G. a. L-carnosine (beta-alanyl-L-histidine) and carcinine (beta-alanylhistamine) act as natural antioxidants with hydroxyl-radical-scavenging and lipid-peroxidase activities. Biochem. J. 1994;304(2):509–516. doi: 10.1042/bj3040509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babizhayev MA, Yegorov YE. Advanced drug delivery of N-acetylcarnosine (N-acetyl-beta-alanyl-L-histidine), carcinine (beta-alanylhistamine) and L-carnosine (beta-alanyl-L-histidine) in targeting peptide compounds as pharmacological chaperones for use in tissue engineering, human di. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 2010;4:198–230. doi: 10.2174/187221110793237547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett A, Liu JL. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome engineering in Drosophila. Methods. 2014;69:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belusic G. ERG in Drosophila. Electroretinograms. 2011:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Benzer S. Behavioral mutants of Drosophila isolated by countercurrent distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1967;58:1112–1119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.3.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakely RD, Edwards RH. Vesicular and plasma membrane transporters for neurotransmitters. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borycz J, Borycz JA, Edwards TN, Boulianne GL, Meinertzhagen IA. The metabolism of histamine in the Drosophila optic lobe involves an ommatidial pathway: β-alanine recycles through the retina. J. Exp. Biol. 2012;215:1399–411. doi: 10.1242/jeb.060699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borycz J, Borycz JA, Loubani M, Meinertzhagen IA. tan and ebony genes regulate a novel pathway for transmitter metabolism at fly photoreceptor terminals. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:10549–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10549.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borycz J, Vohra M, Tokarczyk G, Meinertzhagen IA. The determination of histamine in the Drosophila head. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2000;101:141–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borycz JA, Borycz J, Kubów A, Kostyleva R, Meinertzhagen IA. Histamine compartments of the Drosophila brain with an estimate of the quantum content at the photoreceptor synapse. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1611–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.00894.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann A, Grosche A, Pannicke T, Reichenbach A. GABA and Glutamate Uptake and Metabolism in Retinal Glial (Müller) Cells. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2013;4:48. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bröer S, Brookes N. Transfer of glutamine between astrocytes and neurons. J. Neurochem. 2001;77:705–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg MG, Sarthy PV, Koliantz G, Pak WL. Genetic and molecular identification of a Drosophila histidine decarboxylase gene required in photoreceptor transmitter synthesis. EMBO J. 1993;12:911–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi R, Reddig K, Li H-S. Long-distance mechanism of neurotransmitter recycling mediated by glial network facilitates visual function in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014;111:2812–2817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323714111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Sakurai E, Hu W, Jin C, Kiso Y, Kato M, Watanabe T, Wei E, Yanai K. Pharmacological effects of carcinine on histaminergic neurons in the brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;143:573–580. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C, Ross LS, Cohen BN, Lester HA, Gill SS. The transporter-like protein inebriated mediates hyperosmotic stimuli through intracellular signaling. J. Exp. Biol. 2000;203:3531–46. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.23.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards TN, Meinertzhagen IA. The functional organisation of glia in the adult brain of Drosophila and other insects. Prog. Neurobiol. 2010;90:471–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsworth JD, Roth RH. Dopamine synthesis, uptake, metabolism, and receptors: relevance to gene therapy of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 1997;144:4–9. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farthing CA, Sweet DH. Expression and function of organic cation and anion transporters (SLC22 family) in the CNS. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014;20:1472–1486. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flancbaum L, Brotman DN, Fitzpatrick JC, Es T, Van, Kasziba E, Fisher H. Existence of carcinine, a histamine-related compound, in mammalian tissues. Life Sci. 1990;47:1587–1593. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90188-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MR, Doherty J. Glial cell biology in Drosophila and vertebrates. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadea A, López-Colomé AM. Glial transporters for glutamate, glycine and GABA I. Glutamate transporters. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001;63:453–60. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin BA, Arruda SE, Dolph PJ. The role of carcinine in signaling at the Drosophila photoreceptor synapse. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz SJ, Cummings AM, Nguyen JN, Hamm DC, Donohue LK, Harrison MM, Wildonger J, O’connor-Giles KM. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics. 2013;194:1029–1035. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.152710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves MW, Sabroe RA. Histamine: the quintessential mediator. J. Dermatol. 1996;23:735–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1996.tb02694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka Y, Meinertzhagen IA. Immunocytochemical localization of synaptic proteins to photoreceptor synapses of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 2010:1133–1155. doi: 10.1002/cne.22268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Gong P, Reddig K, Mitra M, Guo P, Li HS. The Fly CAMTA Transcription Factor Potentiates Deactivation of Rhodopsin, a G Protein-Coupled Light Receptor. Cell. 2006;127:847–858. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC, Raghu P. Visual transduction in Drosophila. Nature. 2001;413:186–193. doi: 10.1038/35093002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg M. Separation of receptor and lamina potentials in the electroretinogram of normal and mutant Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 1971;55:85–100. doi: 10.1242/jeb.55.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huszti Z, Prast H, Tran MH, Fischer H, Philippu A. Glial cells participate in histamine inactivation in vivo. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 1998;357:49–53. doi: 10.1007/pl00005137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito C. The role of brain histamine in acute and chronic stresses. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2000;54:263–267. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(00)80069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutel M, Akdis M, Akdis C. a. Histamine, histamine receptors and their role in immune pathology. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2009;39:1786–1800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepsell H. The SLC22 family with transporters of organic cations, anions and zwitterions. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013;34:413–435. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan Z, Reddig K, Li H-S. Loss of Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase in Drosophila photoreceptors leads to blindness and age-dependent neurodegeneration. Exp. Neurol. 2014;261:791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie SM, Howells AJ, Cox GB, Ewart GD. Sub-cellular localisation of the white/scarlet ABC transporter to pigment granule membranes within the compound eye of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetica. 2000;108:239–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1004115718597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchette LD, Wang H, Li F, Babizhayev MA, Kasus-Jacobi A. Carcinine has 4-hydroxynonenal scavenging property and neuroprotective effect in mouse retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:3572–83. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinertzhagen IA, O’Neil SD. Synaptic organization of columnar elements in the lamina of the wild type in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Comp. Neurol. 1991;305:232–63. doi: 10.1002/cne.903050206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C. Drosophila visual transduction. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:356–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuutinen S, Panula P. Histamine in neurotransmission and brain diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010;709:95–107. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8056-4_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panula P, Nuutinen S. The histaminergic network in the brain: basic organization and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:472–87. doi: 10.1038/nrn3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passani MB, Bacciottini L, Mannaioni PF, Blandina P. Central histaminergic system and cognition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000;24:107–13. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendahl KG, Jones KR, Kulkarni SJ, Bagully SH, Hall JC. The dissonance mutation at the no-on-transient-A locus of D. melanogaster: genetic control of courtship song and visual behaviors by a protein with putative RNA-binding motifs. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:390–407. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00390.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardt A, Rybak J, Störtkuhl KF, Meinertzhagen IA, Hovemann BT. Ebony protein in the Drosophila nervous system: optic neuropile expression in glial cells. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002;452:93–102. doi: 10.1002/cne.10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Calderón R, Uhlenbrock G, Borycz J, Simon AF, Grygoruk A, Yee SK, Shyer A, Ackerson LC, Maidment NT, Meinertzhagen IA, Hovemann BT, Krantz DE. A glial variant of the vesicular monoamine transporter is required to store histamine in the Drosophila visual system. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth FC, Draguhn A. GABA metabolism and transport: effects on synaptic efficacy. Neural Plast. 20122012:805830. doi: 10.1155/2012/805830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Marie, Carlson SD. Interneuronal and glial-neuronal gap junctions in the lamina ganglionaris of the compound eye of the housefly, Musca domestica. R.L. Cell Tissue Res. 1985;241:43–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00214624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarthy PV. Histamine: a neurotransmitter candidate for Drosophila photoreceptors. J. Neurochem. 1991;57:1757–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb06378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert ML. Gastric secretion. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2010;26:598–603. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833f2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert ML, Peura DA. Control of Gastric Acid Secretion in Health and Disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;134:1842–1860. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark WS, Carlson SD. Ultrastructure of capitate projections in the optic neuropil of Diptera. Cell Tissue Res. 1986;246:481–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00215187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenesen D, Moehlman AT, Kramer H. The carcinine transporter CarT is required in photoreceptor neurons to sustain histamine recycling. Elife. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.10972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar MM. Histamine in the regulation of wakefulness. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011;15:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, An F, Borycz JA, Borycz J, Meinertzhagen IA, Wang T. Histamine Recycling Is Mediated by CarT, a Carcinine Transporter in Drosophila Photoreceptors. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa T, Naganuma F, Iida T, Nakamura T, Harada R, Mohsen AS, Kasajima A, Sasano H, Yanai K. Molecular mechanism of histamine clearance by primary human astrocytes. Glia. 2013;61:905–16. doi: 10.1002/glia.22484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu LJ, Holmes BR, Aronin N, Brodsky MH. CRISPRseek: a bioconductor package to identify target-specific guide RNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing systems. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Nern A, Zipursky SL, Frye M. a. Peripheral Visual Circuits Functionally Segregate Motion and Phototaxis Behaviors in the Fly. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler AB, Brüsselbach F, Hovemann BT. Activity and coexpression of Drosophila black with ebony in fly optic lobes reveals putative cooperative tasks in vision that evade electroretinographic detection. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013;521:1207–24. doi: 10.1002/cne.23247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.