Abstract

Background

Challenges of recruiting participants into pragmatic trials, particularly at the level of the health system, remain largely unexplored. As part of Strategies and Opportunities to STOP Colon Cancer in Priority Populations (STOP CRC), we recruited eight separate community health centers (consisting of 26 individual safety net clinics) into a large comparative effectiveness pragmatic study to evaluate methods of raising the rates of colorectal cancer screening.

Methods

In partnership with STOP CRC’s advisory board, we defined criteria to identify eligible health centers and applied these criteria to a list of health centers in Washington, Oregon, and California affiliated with OCHIN (formerly Oregon Community Health Information Network), a 16-state practice-based research network of federally sponsored health centers. Project staff contacted centers that met eligibility criteria and arranged in-person meetings of key study investigators with health center leadership teams. We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to thematically analyze the content of discussions during these meetings to identify major facilitators of and barriers to health center participation.

Results

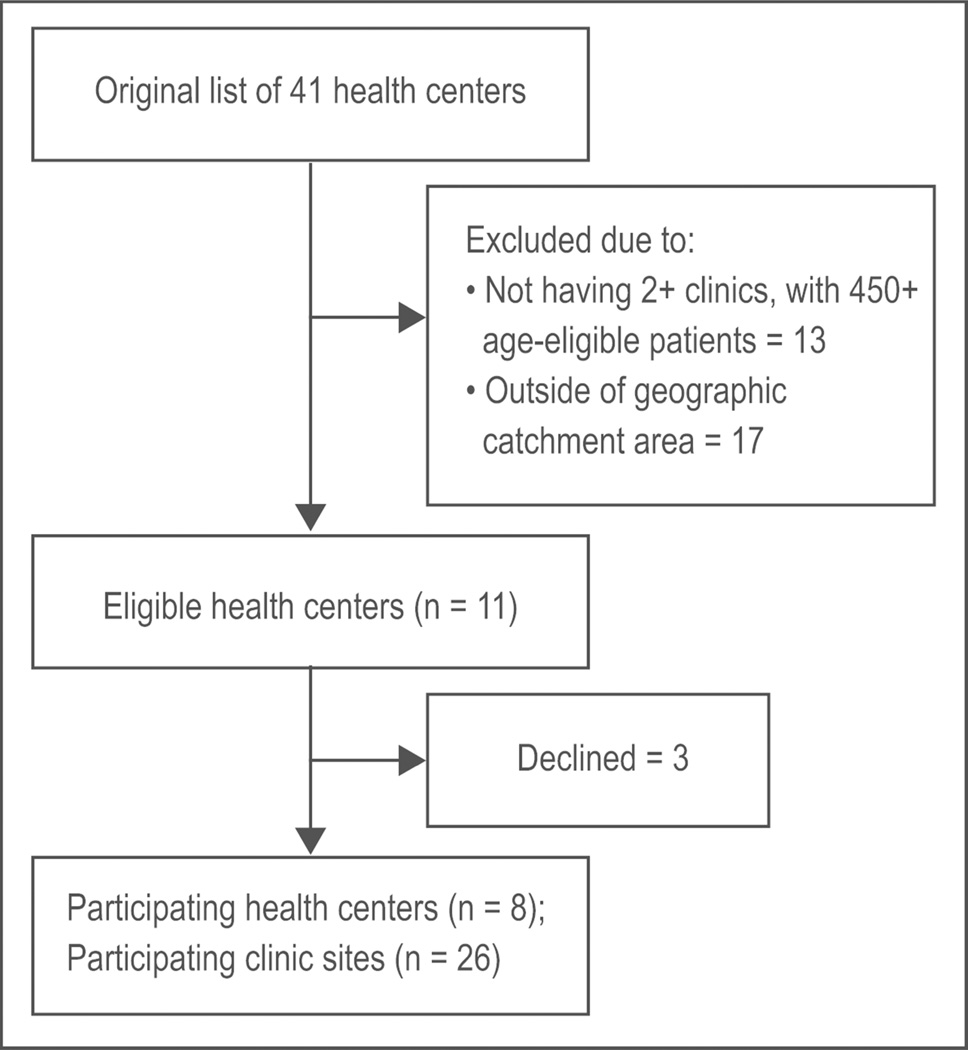

From an initial list of 41 health centers, 11 met the initial inclusion criteria. Of these, leaders at three centers declined and at eight centers (26 clinic sites) agreed to participate (73%). Participating and nonparticipating health centers were similar with respect to clinic size, percent Hispanic patients, and percent uninsured patients. Participating health centers had higher proportions of Medicaid patients and higher baseline colorectal cancer screening rates. Common facilitators of participation were perception by center leadership that the project was an opportunity to increase colorectal cancer screening rates and to use electronic health record tools for population management. Barriers to participation were concerns of center leaders about ability to provide fecal testing to and assure follow up of uninsured patients, limited clinic capacity to prepare mailings required by the study protocol, discomfort with randomization, and concerns about delaying program implementation at some clinics due to the research requirements.

Conclusion

Our findings address an important research gap and may inform future efforts to recruit community health centers into pragmatic research.

Keywords: Clinic recruitment, pragmatic trial, colorectal cancer screening, federally qualified health centers, safety net clinics

Background

Relatively little is known about the successes and challenges of recruiting health care organizations and clinics to participate in large pragmatic multisite studies. Even less is known about the content of materials used to recruit health care sites. This lack of knowledge may be due to the fact that most site recruitment occurs prior to submission of funding applications or proposals and often relies on nonsystematic methods. Recruited sites are often those with whom a researcher has an established relationship. Even where systematic methods are used, nonparticipating sites rarely provide data on their characteristics or provide viewpoints of staff that would allow meaningful comparisons with participating sites. As a result, little is known about the characteristics of nonparticipating sites or clinic level factors that may influence willingness to participate, even though differential participation may limit the potential for generalization of study findings. Instead, questions about representativeness typically have emphasized comparability across randomized sites, with little attention paid to sites that declined to participate.

Recruiting sites to participate in pragmatic trials is time intensive, both from the perspective of preparing materials and of organizing face-to-face meetings with staff and clinic leaders. Therefore, information about how recruitment has been achieved, materials used, and discussion of what worked and what may not have worked may inform estimation of resource needs for other researchers who wish to accomplish similar goals.

As part of Strategies and Opportunities to STOP Colon Cancer in Priority Populations (STOP CRC), we engaged in a systematic process to recruit federally-sponsored health centers to participate in a large multisite pragmatic trial aimed at raising the rates of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. We report both quantitative and qualitative data using criteria developed by Gaglio et al.;1 that is, the percentage of sites approached that agreed to participate, characteristics of participating and nonparticipating sites, and qualitative summaries of notes taken during “recruitment” meetings with leadership teams (both participating and nonparticipating). These findings fill an important research gap and may inform future efforts to recruit health centers into pragmatic research.

Methods

Study setting

STOP CRC is a large, multisite, cluster randomized pragmatic study that is testing the effectiveness of an electronic health record (EHR) leveraged automated mailed fecal immunochemical test program to increase CRC screening rates in safety net clinics. This project is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory program (UH2AT007782/ 4UH3CA18864002), whose aim is to provide a framework of implementation methods and best practices that will enable the participation of many and varied healthcare systems in clinical research.2 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaiser Permanente Northwest (Protocol # 4364), with ceding agreements from Group Health Research Institute and OCHIN (formerly Oregon Community Health Information Network). The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01742065).

STOP CRC pragmatic study

There are two features of our study that made it particularly suitable for an analysis of recruitment of health centers. First, the study involved a collaboration with OCHIN, an EHR vendor that provides an EHR system, including Epic© (version 2014; Verona, WI) and other health information technology services to more than 70 health service organizations (referred to as health centers) with more than 250 individual clinics. OCHIN supports research through its practice-based research network, giving us an opportunity to identify multiple sites within the network, to screen them for suitability, and to approach those selected. Second, we worked with our advisory board to define clinic-level eligibility criteria and systematically applied these criteria to the clinics affiliated with OCHIN.

Clinic level eligibility criteria

Of the eligibility criteria that our Advisory Board helped to establish, some were related to the health center and others to the clinics comprising the health centers (Table 1). In all cases, the health center leadership made the decision whether to participate. We applied eligibility criteria in three successive steps. Early on, we chose to limit our recruitment to sites in relative close proximity to our research office in Portland, Oregon, i.e., health centers geographically located in Washington, Oregon, and northern California. Additionally, each health center had to have at least two clinics so that we could randomize clinic sites within a health center; each clinic had to have a minimum of 450 patients aged 50 to 74 years. As an initial step, the OCHIN network provided the research team with a list of health centers that met these criteria (n = 11). We applied a second set of criteria following meetings with health center leadership. These included: 1) willingness to randomize eligible clinics, with the caveat that at least one would be assigned to the study intervention and at least one to usual care; 2) willingness to use a single type of screening test in all participating clinics; 3) availability of a laboratory that had sufficient capacity to process screening tests to be used in STOP CRC; 4) an electronic interface with the laboratory processing screening tests (if tests are processed at an outside laboratory); 5) sufficient capacity to obtain colonoscopies for patients who screened positive on fecal testing; 6) a plan for screening and follow-up for uninsured patients; 7) willingness to fulfill research requirements (clinic interviews, data validation, attendance at regular advisory board meetings, interpretation of project findings); 8) willingness to implement the STOP CRC program; and 9) agreement to cede IRB responsibility for STOP CRC to Kaiser Permanente Northwest and to maintain an active federal-wide assurance.

Table 1.

Health Center and Clinic Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Health Center and Clinic Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Clinic size | Clinics must have 450+ patients aged 50 – 74. |

| Number of clinic sites in health center | Health centers must have at least 2 clinic sites that meet the size requirement. |

| Fecal test | Health centers must agree to use the same screening method in its intervention and usual care clinics. |

| Colonoscopy capacity | Communities must have sufficient capacity to perform colonoscopies for patients who screen positive. |

| Laboratory interface/capacity | Clinic sites must have a direct interface with the laboratory that processes screening tests; the laboratory has sufficient capacity to process tests. |

| Randomization of clinics | Health center must agree to randomization of their eligible clinics; at least one will be assigned to the intervention arm and one to the usual care arm. |

| Coverage of the uninsured | Health center must develop a plan for fecal testing and follow-up care among uninsured patients. |

| Research requirements | Consent to study requirements for clinic interviews, data validation, participation in regular advisory board meetings and interpretation of trial findings. |

| Prioritization/willingness | Health center leadership must prioritize colon cancer screening, review baseline screening rates and set improvement targets. |

| Human Subjects requirements | Health center must agree to cede IRB responsibilities to the Center for Health Research. |

| Federal Wide Assurance | Health center must have active federal wide assurance. |

Recruitment materials

We prepared recruitment materials that included a slide presentation about the program and a packet of handouts on the project. The slide presentation addressed the STOP CRC opportunity and included: 1) findings from the pilot STOP CRC study, i.e., a 37% increase in CRC screening rates among intervention patients;3 2) clinic-level inclusion criteria; 3) project activities; 4) clinic sizes (obtained from OCHIN) and estimated number of screening tests that would be completed and colonoscopies needed based on test results; and 5) the proposed project timeline. Additional slides provided the rationale for fecal testing4,5 and, based on the work of Vart and others,6 presented the results of a systematic review of patients’ adherence to fecal testing by different methods. To encourage endorsement of fecal testing, we presented findings from studies showing that patients prefer fecal testing over colonoscopy.4,5 We assembled packets that contained copies of the presentation, a draft scope of work, a draft budget and budget justification, and prototype letters of support. We also provided a summary of the peer-reviewed literature on the performance characteristics of fecal screening tests, as many clinics were using a 3-sample guaiac-based test and were seeking technical assistance in choosing a fecal immunochemical test (FIT).

Recruitment procedures

Recruitment meetings typically included individuals in health center-wide roles: the center’s medical director, operations director, quality improvement leader, clinical program director, and sometimes a laboratory director. Meetings were scheduled for 2 hours. The STOP CRC co-principal investigator (co-PI) delivered the presentation and the community research liaison, who had many years of experience working on health care transformation efforts with health centers, facilitated the meetings. Most meetings also were attended by the project’s lead qualitative researcher. During the meetings, the project qualitative researcher recorded field notes based on the discussions. Meetings were neither audio- or videotaped.

In order to obtain more information from non-participating sites, we sought to conduct interviews with members of the leadership teams of these sites. We contacted medical directors from each nonparticipating health center and invited them to participate in a one-on-one interview. We also asked the medical director for permission to interview additional members of the leadership who were involved in the early recruitment discussions or would typically be involved in implementing this type of effort (e.g. operations director, project manager). The interviews lasted about 30 minutes and addressed participation barriers and whether their level of interest in participating had changed since the initial solicitation. The interviews took place between December 2014 and February 2015, about nine months following the start of the trial.

Data collection and analysis

Consistent with reporting criteria for the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework7 we report four aspects of clinic- level participation: 1) Sites excluded (percent and reasons why); 2) sites approached that participated; 3) characteristics of participating and nonparticipating sites; and 4) qualitative factors related to participation. We created qualitative summaries of notes from recruitment meetings with leadership teams that had been recorded by the community research liaison and qualitative researcher. The qualitative researcher and co-PI used these summaries to identify barriers and facilitators to participation of health centers. We identified themes and subthemes and used components of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to group facilitators and barriers by factors related to the external context, the internal context, and intervention attributes.

Results

Site recruitment

OCHIN staff gave us a list of 41 health centers that were federally qualified, rural health centers or public health departments. We excluded 13 health centers because they did not meet the size requirements or had only a single clinic and excluded an additional 17 centers because they were outside our pre-specified geographic catchment area (Figure 1). Of the remaining 11 eligible health centers, the leadership of three declined to participate; of these three, representatives from one health center agreed to talk to the STOP CRC PI by telephone but declined an in-person meeting with the research team and the other two centers declined after in-person meetings. Thus, recruitment success at the health center level was 73% (8/11) of those eligible to participate. The final sample of eight participating health centers included 28 clinic sites; leaders of one health center with six sites agreed to the participation of four of their sites; thus, clinic-level recruitment was 26/28 (93%). The estimated number of active patients aged 50 to 74 at the 26 sites was approximately 30,000. Recruitment activities took place between August 2013 and January 2014.

Figure 1.

We gathered data from a total of 7 individuals representing the three non-participating health centers. Of these, 6 participated in 30 minute telephone interviews and were leaders of two of the nonparticipating health centers: 2 medical directors, 2 operations directors, and 2 project managers. Interviews were conducted between November 2014 and January 2015. The medical director at one health center declined participation in the interview, but responded to a brief subset of questions sent by email.

Health center data from 2013 showed similar proportions of Hispanic patients in participating and nonparticipating health centers (2% –36% and 4% – 37%, respectively; Table 2). The proportion of patients who were uninsured varied considerably in participating health centers (2% – 50%) but varied less in nonparticipating health centers (23% – 30%). The proportion of patients enrolled in Medicaid was higher in participating sites than nonparticipating sites (14% – 37% vs. 4% – 16%). In 2013, participating health centers had higher 2013 CRC screening rates (20% – 53% vs. 10% – 16%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of participating and nonparticipating health centers*

| N clinics |

State | Overall clinic size |

No. of patients aged 50 to 74 yrs |

% Hispanic |

% uninsured |

% Medicaid |

Baseline CRC screening rate** |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participating Health Centers | ||||||||

| Health Center 1 | 2 | OR | 2765 | 886 | 9 | 49 | 15 | 20 |

| Health Center 2 | 3 | OR | 4573 | 1898 | 7 | 38 | 17 | 23 |

| Health Center 3 | 3 | OR | 9148 | 3070 | 17 | 50 | 14 | 20 |

| Health Center 4 | 6 | OR | 23616 | 7215 | 14 | 33 | 37 | 39 |

| Health Center 5 | 4 | OR | 11213 | 3959 | 10 | 40 | 15 | 33 |

| Health Center 6 | 4 | CA | 18476 | 6584 | 5 | 2 | 19 | 53 |

| Health Center 7 | 2 | OR | 12004 | 4161 | 2 | 11 | 20 | 33 |

| Health Center 8 | 2 | OR | 7697 | 2125 | 36 | 37 | 26 | 34 |

| Nonparticipating Health Centers | ||||||||

| Health Center A | 5 | WA | 10182 | 3603 | 4 | 23 | 12 | 16 |

| Health Center B | 2 | OR | 4359 | 1455 | 37 | 30 | 5 | 14 |

| Health Center C | 4 | OR | 4887 | 1383 | 15 | 30 | 16 | 14 |

Data are from 1/1/2013 12/31/2013;

CRC = colorectal cancer; Percentage of patients aged 50 to 75 with a clinic visit in the past year who are up to date based on EHR evidence of having had a fecal testing in the past year, a sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 years or a colonoscopy in the past 10 years

Themes identified from meetings with health center leaders

From field notes taken during center recruitment meetings, we organized the facilitators of and barriers to center recruitment by three constructs, External Setting, Internal Setting, and Intervention Attributes (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Salient facilitators to health center participation in STOP CRC*

| Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Construct/Theme/Subtheme |

|---|

| External Setting |

Colorectal cancer screening is a high priority

|

| Internal Setting |

Proposed program will provide support for needed change

|

Proposed program can catalyze additional change

|

| Intervention attributes |

Clinics are offered choice and flexibility

|

Success of pilot study/phase demonstrates credibility of STOP CRC and supports efficacy of the intervention

|

Strategies and Opportunities to STOP Colon Cancer in Priority Populations

Table 4.

Salient barriers to health center participation in STOP CRC*

| Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Construct/Theme/Subtheme | Endorsed by clinic that declined participation |

|---|---|

| External Setting | |

Concerns about the cost of testing or follow up care for uninsured patients

|

Yes |

|

|

Concerns about clinic capacity

|

Yes Yes Yes |

Competing priorities

|

Yes Yes Yes |

|

|

Concerns with randomization of clinics

|

Yes |

Concerns proposed program will not work

|

Yes Yes |

Strategies and Opportunities to STOP Colon Cancer in Priority Populations

Facilitators of health center participation in STOP CRC

External setting: CRC screening is a high priority

Several health center leaders expressed interest in raising rates of CRC screening among their clinic patients. These leaders stated that their low rates of screening provoked feelings of guilt or regret; many stated that more attention needed to be paid to such screening. Several leaders noted that their state or Medicaid Health Plans were offering incentives to centers that met targeted rates of CRC screening.

Internal setting: STOP CRC provides support for needed change

Among health center leaders who wanted to place a greater emphasis on CRC screening, several viewed the project as an opportunity to receive needed support and encouragement to do so. Many leaders reported being enthusiastic about the project, as it did not require their patients to make additional clinic visits. They also perceived a central, automated reminder approach to be beneficial, as clinicians sometimes missed the opportunity to address CRC screening during routine clinic visits.

STOP CRC can catalyze additional change

Several health center leaders stated that participation in the project would support their growth or learning and leverage improvements they planned to make in preventive care outreach. Some health center leaders noted that the project provided an opportunity to change the type of screening test currently used. Other health centers were in the process of developing an overarching plan for addressing preventive health care in their clinics; leaders at those centers said that STOP CRC provided motivation to start with CRC screening. Leaders at other centers noted the advantage of using EHR tools made available through the project, such as the Health Maintenance and Reporting Workbench in Epic, to track preventive care. They also recognized that the program could improve the quality and availability of CRC screening data.

Intervention attributes: STOP CRC offers choice and flexibility

Health center leaders approved flexibility within STOP CRC regarding the type of fecal screening test used, the starting date for clinic participation, and the implementation approach (i.e., a monthly mailing to patients with birthdays during the month, a quarterly mailing, or a one-time mailing).

Success of STOP CRC pilot study provides credibility and supports efficacy of the intervention

The success of the pilot study, conducted in the first year of the STOP CRC program at a health center with which leaders of all sites were familiar, lent both credibility and a sense of efficacy to the program. Some health center leaders noted that their clinics were similar to the health center that had implemented the pilot study. Patient outreach materials, including introductory letters, wordless instruction8 and reminder postcards were perceived to be patient friendly, to add value, and to be easily adapted for use by clinic personnel.

Barriers to Health Center Participation in STOP CRC

External setting: Concerns about coverage of costs for uninsured patients and resources available for follow up care

Some health center leaders expressed concern about a long term solution for providing CRC screening tests and follow-up colonoscopy when indicated for uninsured patients. Many noted that there was low capacity for colonoscopy in their communities and limited community resources to pay for services for the uninsured. After we presented the estimated number of uninsured patients who would need a colonoscopy, many center leaders were reassured and were able to identify community resources that could provide sufficient low-cost services for that number. Others noted that the available resources for colonoscopy varied by clinic within their health centers.

Internal setting: Concerns about clinic capacity

Most health center leaders expressed concerns about the capacity of clinics to implement the program with existing personnel given priorities already established. One leader who expressed this concern invited the STOP CRC co-PI to speak to the lead physicians at clinics within the health center to generate support and buy in. Some sites were experiencing turnover in key leadership positions, which could affect both capacity and local priorities. With respect to CRC screening, some health center leaders expected internal resistance to changing the type of fecal screening test in current use. Other health center leaders expected it to be difficult to implement a single test across all sites, as agreements with laboratories varied among clinics. Other concerns were specific to individual clinics, as some historically faced greater challenges in implementing quality improvement programs, typically due to variations by clinic in staffing resources. Small and remote clinics are generally at greater risk of provider shortages; they may consolidate staffing roles in a single position and have less interaction with central health center administration.

Competing priorities

A few health center leaders noted that they had not raised CRC screening to a high priority. Most leaders cited competing priorities and the rapidly changing external environment. Competing priorities included opening a new clinic, upgrading to a new release of Epic, and planning an overarching preventive care outreach strategy. Leaders from these health centers desired to address CRC screening at a later date to allow more time to develop this strategy.

Intervention attributes: Discomfort with delaying implementation for some clinics

Many health center leaders expressed confusion about the meaning of randomization and how it would work for their clinics. Some understood randomization to mean that their health center would either be chosen or not; others expected that some patients within a clinic would get the intervention and others would not. Several health center leaders were reassured once we explained randomization of clinic sites, i.e., some of their clinic sites, along with the patients at those clinics, would be assigned to the intervention arm. Discomfort with randomization of clinics was expressed by only a few health center leaders, primarily those at centers that elected not to participate in the study. Some leaders whose clinics had begun to prioritize CRC screening expressed concern that participating in the study could cause them to delay implementation of CRC screening. Others stated that not implementing the intervention simultaneously in all clinics of their health center was counter to their mission of ensuring equal access and care for all patients. Randomization of clinics also meant that health centers leaders would not be able to select the intervention arm clinics that they perceived to be the most prepared to implement the intervention; some clinic sites might find it challenging to implement the intervention because of staff turnover, clinic size, geographic distance from health center headquarters, or other reasons.

Concerns that the STOP CRC intervention will not work

Some health center leaders expressed skepticism about the potential effectiveness of the intervention at their site. For example, some expressed concerns about using a mailed fecal screening test approach with some of the more challenging clinic patients, e.g., those living in geographically remote regions or those who spoke non-English languages, had low levels of literacy, or lacked awareness of the importance of screening. Others were concerned about the proportion of patients who had a reliable mailing address. Still others noted that their providers did not support fecal testing and some believed that colonoscopy was the standard of care and should be offered to all their patients.

Findings from interviews with leadership of non-participating health centers

In general, leaders of non-participating health centers stated that CRC screening was not a high organizational or provider priority; the clinics had no organized approach to screening and thus were not prepared to implement a program like STOP CRC. Representatives from all three health centers noted that their organizations were facing financial strain that required they limit quality improvement and outreach efforts. Similarly, two of the non-participating health centers were concerned that participating in STOP CRC would require that their organization divert resources from other high priority areas; additionally they cited high staff turnover (in leadership and frontline roles) that made participation unrealistic. Other barriers included concerns about providing screening and follow-up colonoscopy to patients who lacked health care insurance and the perception that, by requiring randomization of clinic sites, the project misaligned with goal to develop an efficient, centralized process for outreach (across multiple cancer screening tests). Two of the sites were participating in another funded initiative to improve rates of CRC screening; leaders from those sites expressed concerns that the initiatives were incongruous.

The leaders of the three refusing health centers indicated they would be amenable now to participating in a program like STOP CRC as many of the barriers mentioned above have been overcome or have lessened. Specifically, they cited the Affordable Care Act that had reduced the proportion of patients who lacked health insurance and made concerns about the costs of screening or follow up procedures less worrisome. Also, most sites had switched to an improved fecal test (FIT) with which both providers and patients expressed greater satisfaction; were more stable in terms of staffing and financial resources, and were more experienced in centralizing outreach efforts. One leader from one health center continued to remain concerned that randomizing clinics would result in withholding services to patients in usual care clinics but expressed willingness to consider randomizing clinics given that the barriers cited above had lessened.

Discussion

We explored facilitators of and barriers to participation of federally-sponsored health centers in a pragmatic study to evaluate a clinic-based intervention designed to raise the rates of CRC screening. Our findings revealed that leaders of many centers were willing to participate in the study in order to promote CRC prevention and obtain technical assistance to acquire skills needed to leverage change. Health center leaders noted the importance of offering flexibility in intervention implementation that could accommodate clinics’ multiple priorities. The barriers to participation that we identified included concerns about providing affordable screening and follow up services to uninsured patients, discomfort with randomization of clinics, either because it is antithetical to their mission or may require that they rollout the intervention to clinics that are understaffed, located in geographically remote regions, or have historically struggled to implement improvement initiatives. Other clinic leaders noted low prioritization of CRC screening in general and fecal testing in particular. Leaders often expressed worries about clinics’ staffing capacity.

The experience with recruitment at the health system level may be particularly important in pragmatic research, where the external validity of study findings is central to the question of whether similar results could be achieved in other similar settings. Most previous evaluations of clinic-based programs that address cancer screening have reported rates of study participation at the patient level and ignored the characteristics of clinics that opted not to participate. We argue that clinic non-participation may be an important source of selection bias often ignored in other research and that our results apply most readily to facilities with a history of interest and commitment to CRC screening.

Our quantitative analyses show discernible differences in the patient demographic characteristics of eligible health centers that participated and those that did not. Compared to non-participating health centers, participating health centers had a higher proportion of patients enrolled in Medicaid and were up-to-date with CRC screening recommendations. These findings suggest that health centers already taking steps to improve CRC screening rates were more willing to participate in our trial. This differential participation may suggest that our results apply specifically to health centers with a demonstrated interest in CRC promotion.

Comparisons between our clinics and a national sample of federally sponsored health centers show key differences in CRC screening and Medicaid enrollment. National data from 2013 from the US Department of Health and Human Services for federally-sponsored health centers show that the average percentage of patients up-to-date with CRC screening is 32.6%, suggesting that our participating health centers were more similar than our non-participating health centers to this national sample.9 The same national data show that the average percentage of patients enrolled in Medicaid is 41.5%, higher than in all our eligible health centers (participating and non-participating).9 These comparisons show a mixed picture of the validity of our trial for health centers nationally.

Strong engagement and trusting relationships with clinic leadership routinely is cited as a key factor in the success of any learning activity.10,11 We took several steps to ensure maximal success in our health center recruitment effort. First, we presented findings from a pilot study conducted at a clinic with which health center leaders were familiar; thus, they believed they would have similar success at their site. Next, we presented information specific to their clinics to show the number of patients expected to need follow-up colonoscopy based on anticipated improvements in their fecal screening rates. We engaged the entire leadership team, not just the medical director. We also traveled to most sites to present in-person to build trust and establish credibility. Finally, we answered questions, listened to concerns, and followed up with presentations to providers of clinical care, when needed. The project’s clinic liaison who set up the meetings was familiar with some of the leadership staff at several health centers, which facilitated scheduling and provided credibility. We have put in place an infrastructure that we hope will facilitate continued engagement in the project: quarterly meetings of our advisory board (which includes representatives from all participating health centers) and monthly meetings of EHR site specialists and quality improvement leaders to anticipate and troubleshoot implementation.

Few previous investigations have reported on challenges in recruiting clinics to participate in research. Murray14 and others note specific challenges related to partnerships with primary care clinics; such clinics may shut down unexpectedly or may fail to implement EHRs or other tools on a timeline needed to fulfill research requirements.12 Dietrich et al. showed that leadership stability was key to success in CRC screening at community health centers.13 These finding reinforce the need for clinic level data when conducting pragmatic trials and suggest characteristics of leadership, practice experience, population served, and overall stability need to be recorded.

Our qualitative assessment primarily relied on field notes of recruitment meetings; for practical reasons, we did not record these meetings and do not present quotes. Nevertheless, all meetings were attended by the community liaison, study co-PI, and, in many cases, the lead qualitative researcher; thus, our themes were developed from observations and notes taken by multiple attendees. Moreover, follow-up one-on-one interviews with leadership of non-participating sites were recorded and coded, consistent with standard qualitative research methods.

Conclusions

We present findings from both quantitative and qualitative analysis of factors associated with site participation in a multisite pragmatic study of an intervention intended to raise CRC screening rates. Our findings underscore the importance of assessing and reporting recruitment success at the organizational and/or clinic level in order to know the external validity of the findings and may inform future efforts to select and recruit health systems to participate in pragmatic research.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health through the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine under Award Number UH2AT007782 and the National Cancer Institute under Award Number 4UH3CA18864002. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine or the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01742065

Competing Interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors Contributions

GDC and BBG designed the study and GDC drafted the manuscript; SHT and TB provided oversight in the design and interpretation of results; GDC, SR, and JS met with clinic leadership and gathered data. All authors revewied and approved a final draft.

Authors’ Information

None.

References

- 1.Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e38–e46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIH Common Fund National Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory. [accessed 3 November 2014];2013 http://commonfund.nih.gov/hcscollaboratory/index.

- 3.Coronado GD, Vollmer WM, Petrik AF, et al. Strategies and opportunities to STOP colon cancer in priority populations: pragmatic pilot study design and outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:575–582. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta S, Halm EA, Rockey DC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of fecal immunochemical test outreach, colonoscopy outreach, and usual care for boosting colorectal cancer screening among the underserved: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1725–1732. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vart G, Banzi R, Minozzi S. Comparing participation rates between immunochemical and guaiac faecal occult blood tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2012;55:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, et al. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: What can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44:119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coronado GD, Sanchez J, Petrik A, et al. Advantages of wordless instructions on how to complete a fecal immunochemical test: lessons from patient advisory council members of a federally qualified health center. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:86–90. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0551-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services 2013 Health Center Data - National Program Grantee Data. [accessed 22 May 2015];2015 http://bpch.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx.

- 10.Yawn BP, Dietrich A, Graham D, et al. Preventing the voltage drop: keeping practice-based research network (PBRN) practices engaged in studies. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:123–135. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.01.130026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kreindler SA, Larson BK, Wu FM, et al. The rules of engagement: physician engagement strategies in intergroup contexts. J Health Organ Manag. 2014;28:41–61. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-02-2013-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray DM, Katz ML, Post DM, et al. Enhancing cancer screening in primary care: rationale, design, analysis plan, and recruitment results. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietrich AJ, Tobin JN, Sox CH, et al. Cancer early-detection services in community health centers for the underserved. A randomized controlled trial. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:320–327. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]